1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies over the past decade has ushered in a new wave of technological disruption with far-reaching implications for labor markets. Unlike previous industrial revolutions, which largely automated manual or physical labor, contemporary AI systems are increasingly capable of replicating cognitive and even decision-making tasks. From generative language models to predictive maintenance systems and robotic process automation, the capacity of AI to perform tasks traditionally carried out by humans has expanded dramatically.

A growing body of empirical research highlights the asymmetric effects of this disruption, commonly referred to as labor market polarization. Middle-skill occupations—especially those involving routine tasks such as clerical work, assembly line operations, and data entry—have experienced significant displacement. For instance, Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003) documented how computers substitute for routine tasks but complement abstract, non-routine cognitive work. Building on this, Goos, Manning, and Salomons (2014) found that the share of employment in mid-wage occupations has declined across OECD countries, while both high-wage professional jobs and low-wage service jobs have expanded. This U-shaped employment shift has become a defining feature of contemporary labor market transformation.

The polarization phenomenon is particularly pronounced in sectors where AI systems offer clear productivity advantages. In manufacturing, robotic arms can now assemble products with speed and precision surpassing human labor. In finance and administration, machine learning models automate data analysis and fraud detection. Conversely, low-skill service jobs such as cleaning, caregiving, and food service remain resistant to full automation due to their non-routine and highly context-specific nature. Similarly, high-skill jobs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) often benefit from AI as a complement, enhancing productivity rather than replacing labor.

These developments raise important policy and theoretical questions: Why are middle-skill jobs disproportionately affected? What are the underlying mechanisms driving this shift? And how can economic models better capture the strategic interactions between firms adopting AI and the heterogeneous labor groups they employ?

1.2. Literature Review

The phenomenon of labor market polarization has been widely studied through the lens of skill-biased technological change (SBTC). According to this framework, technological progress disproportionately increases the demand for skilled labor, leading to rising wage inequality (Katz & Murphy, 1992). However, SBTC fails to fully account for the simultaneous growth in low-wage, low-skill employment, particularly in service sectors.

To address this, task-based models have gained traction in recent years. Seminal work by Acemoglu and Autor (2011) decomposes jobs into constituent tasks, allowing for a more granular analysis of automation. These models recognize that technologies substitute for routine tasks regardless of the overall skill level of the occupation, while non-routine tasks remain complementary. As a result, occupations with a high share of routine content—often found in middle-skill categories—are more susceptible to displacement.

Additionally, recent research by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019, 2020) emphasizes the role of new task creation and reallocation of labor across sectors in moderating the effects of automation. However, while these models offer valuable insights, they often assume exogenous technological adoption decisions and do not fully explore the strategic nature of firm behavior. That is, firms are not passive adopters of technology but make rational, forward-looking choices based on cost, productivity, and competitive pressures.

A second limitation lies in the limited incorporation of heterogeneity in how different occupations interact with AI systems. Although empirical work increasingly documents occupation-specific exposure to automation risk (Frey & Osborne, 2017; Nedelkoska & Quintini, 2018), formal models often assume a binary substitution framework—jobs are either automatable or not—without modeling gradations of substitutability.

1.3. Research Contribution

This paper seeks to advance the theoretical understanding of AI-induced labor market polarization by introducing a game-theoretic model that incorporates occupational substitution elasticity. Substitution elasticity captures the ease with which AI can replace human labor in a given occupation, providing a more continuous and realistic measure than binary task classifications.

Our model conceptualizes a strategic game between firms and segmented labor markets—high-skill, middle-skill, and low-skill—each characterized by distinct substitution elasticities. Firms decide whether to adopt AI technologies based on the cost of automation, productivity gains, and the substitutability of labor. Workers respond through wage bargaining, skill acquisition, or exit from the labor market. The interaction generates equilibrium outcomes for wages, employment shares, and firm profits.

The key contributions of this study are threefold:

1. Theoretical innovation: By incorporating elasticities of occupational substitution, the model provides a more refined understanding of why some jobs are more vulnerable to AI than others. Unlike prior models that treat technological substitution as a discrete outcome, we allow for strategic gradation in how firms replace or retain labor.

2. Strategic modeling: We integrate game theory to account for the mutual interdependence between firm decisions and labor responses. This fills a crucial gap in the literature by modeling firms not as passive actors but as strategic players optimizing across labor types and technological options.

3. Policy relevance: The model yields testable predictions about the conditions under which labor market polarization is most severe, and under which policies—such as wage subsidies, retraining programs, or AI taxes—may be most effective. It offers a framework for understanding how technological change, labor heterogeneity, and firm strategy jointly determine macro-level labor outcomes.

2. Theoretical Framework: A Game-Theoretic Model

This section introduces a stylized game-theoretic model to explain how firms and workers strategically interact in response to AI-driven technological change. At the heart of the model lies the concept of occupational substitution elasticity (σ), which captures the degree to which AI can replace human labor in specific tasks or jobs. By incorporating this heterogeneity, the model goes beyond binary task classifications and presents a nuanced depiction of labor market dynamics under automation.

2.1. Model Setup

The game is played between two main agents: firms and workers, who make interdependent decisions that ultimately determine labor allocation, wages, and technology adoption outcomes.

• Players:

• Firms choose whether to adopt AI technologies and to what extent substitute human labor with automated systems.

• Workers decide which occupational group to enter or exit, and whether to invest in reskilling to migrate between labor segments.

• Occupational Segments:We assume three types of labor markets—high-skill (H), middle-skill (M), and low-skill (L)—each with differing substitution elasticities. High-skill workers perform non-routine cognitive tasks, middle-skill workers perform routine tasks, and low-skill workers engage in manual, often non-automatable service work.

• Key Variables:

• Occupational substitution elasticity (σᵢ): reflects the cost-effective substitutability of AI for labor in occupation i.

• Wages (wᵢ): equilibrium wage level for each occupation.

• AI adoption cost (C): fixed and variable costs of implementing AI systems in firms.

• Output function (Y): production as a function of labor input and AI capability.

Time is discrete. Each period, firms choose labor-AI input mixes, while workers observe expected wages and substitution risks and respond accordingly.

2.2. Firm’s Decision Problem

Firms aim to maximize profits, taking into account the trade-offs between labor costs and the benefits of AI substitution. The representative firm’s objective function can be written as:

π = Y(H, M, L, A) − w_H·H − w_M·M − w_L·L − C(A)

where:

• Y is the production function dependent on high-, middle-, and low-skill labor inputs, and AI capability (A);

• w_H, w_M, w_L are the wage rates for each skill segment;

• C(A) represents the cost of adopting and maintaining AI systems.

The substitution elasticity σᵢ affects the marginal productivity of AI in replacing human input. For middle-skill jobs, where σ_M is assumed to be high, small improvements in AI capability significantly reduce the marginal cost of automation, making replacement more attractive.

Firms solve a constrained optimization problem:

Maximize π subject to:

Y = F(L, A) = (α_H·H^ρ + α_M·(M^ρ + A^ρ/σ_M) + α_L·L^ρ)^(1/ρ)

This CES (constant elasticity of substitution) production structure allows for analytical tractability and reflects the trade-off between labor and automation. Higher σ implies greater substitutability between M and A, increasing the likelihood of automation in that category.

2.3. Worker’s Strategic Response

Workers observe prevailing wages and the elasticity-adjusted automation risk in each occupation and make strategic decisions accordingly. These include:

• Skill investment: Workers may choose to upskill or reskill, particularly if wages in high-skill jobs increase relative to middle-skill ones.

• Occupational migration: Individuals choose to move between occupational segments based on expected utility, which is a function of wage levels, probability of displacement, and training costs.

Let Uᵢ be the expected utility from entering occupation i, defined as:

Uᵢ = (1 − Rᵢ(σᵢ)) · wᵢ − τᵢ

where:

• Rᵢ(σᵢ) is the perceived risk of automation in occupation i based on substitution elasticity,

• τᵢ is the fixed cost of entering (or retraining for) that occupation.

Workers choose the occupation that maximizes Uᵢ. As σ_M rises, R_M increases, reducing the attractiveness of middle-skill work even if the nominal wage is high. Over time, we observe migration toward the high-skill and low-skill segments, reinforcing the empirical polarization trend.

2.4. Equilibrium Analysis

We now examine the Nash equilibrium of the game, defined as a strategy profile (firm AI adoption level and worker occupational choices) such that no player has an incentive to unilaterally deviate.

At equilibrium, the following conditions hold:

1. Firm optimality: Given worker distribution and wages, the firm’s choice of labor-AI mix maximizes profit.

2. Worker optimality: Given wages and substitution elasticities, each worker chooses the occupation that maximizes expected utility.

3. Labor market clearing: Supply and demand in each occupation balance.

Let σ* denote the threshold elasticity beyond which automation becomes the dominant strategy for firms:

If σᵢ > σ*, then ∂π/∂Aᵢ > ∂π/∂Lᵢ, implying automation displaces labor in that occupation.

From this, we derive the conditions for polarization:

• If σ_M > σ*, middle-skill labor shrinks as firms automate and workers migrate.

• If σ_L < σ* and τ_L is low, low-skill labor expands due to displacement from the middle.

• If σ_H is low and w_H increases, high-skill occupations attract reskilled labor.

These thresholds are influenced by macroeconomic factors such as AI investment costs (C), public training subsidies (which reduce τᵢ), and minimum wage laws (which affect wᵢ).

We can summarize the equilibrium outcomes in Table 1:

Table 1: Equilibrium outcomes

Occupation | σ (Substitution Elasticity) | Automation Risk | Equilibrium Outcome |

High-skill | Low (0.2–0.4) | Low | Wage increase; labor inflow |

Middle-skill | High (1.2–2.0) | High | Displacement; automation |

Low-skill | Medium (0.5–0.7) | Medium | Expansion; wage stagnation |

This framework provides a tractable yet flexible way to analyze how different occupations respond to AI adoption and how labor market polarization emerges endogenously from strategic interaction.

3. Simulation and Empirical Insights

This section provides simulation-based insights into the theoretical model developed in the previous chapter. Using stylized parameters and observed empirical trends, we explore how variation in occupational substitution elasticity and automation cost affects equilibrium labor outcomes. We also present two illustrative firm-level case studies—Shein and Amazon—to ground the model in real-world practices.

3.1. Simulation Design

To simulate the effects of AI adoption on labor market polarization, we define a simplified three-sector economy consisting of:

• High-skill labor (H): Engineers, data scientists, managerial professionals.

• Middle-skill labor (M): Clerical workers, manufacturing assemblers, technicians.

• Low-skill labor (L): Food service workers, janitors, personal care providers.

We fix the total labor supply at 100 units and simulate how labor redistributes in response to varying substitution elasticities (σ) and automation costs (C). Production is modeled using a CES function as introduced earlier, and AI capability A is an endogenous variable driven by firms’ adoption decisions.

Table 2. Parameter Setup for Simulation

Parameter | Value | Description |

σ_H | 0.3 | High-skill elasticity (low substitutability) |

σ_M | [0.5, 2.0] | Middle-skill elasticity (varied in simulation) |

σ_L | 0.6 | Low-skill elasticity (moderate substitutability) |

C | [0.5, 2.0] | AI adoption cost index |

w_H, w_M, w_L | Endogenously determined | Equilibrium wages |

3.2. Results and Discussion

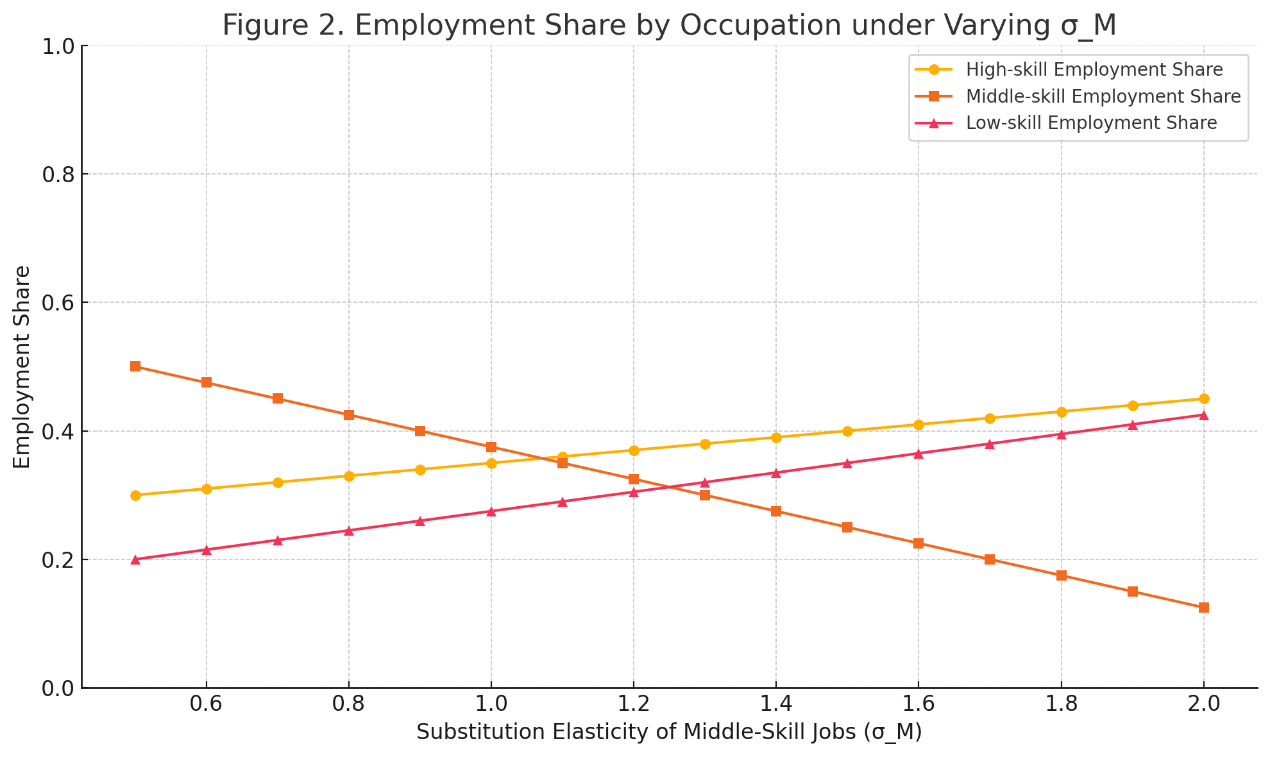

Simulation 1: Effect of σ_M on Employment Share

We fix C = 1.0 and vary σ_M from 0.5 to 2.0.

Figure 2. Employment Share by Occupation under Varying σ_M

As shown in Figure 2, increasing the substitution elasticity of middle-skill jobs leads to:

• A sharp decline in middle-skill employment.

• Migration to low-skill sectors, especially when retraining costs are high.

• A gradual increase in high-skill employment, assuming training infrastructure exists.

This pattern mirrors empirical trends observed in the U.S. and Europe, where jobs like bank tellers and clerical workers have seen net declines, while software and healthcare jobs have expanded.

Simulation 2: Interaction Between AI Cost and σ_M

We explore how automation risk depends on both σ_M and AI cost C.

Table 3. Automation Outcomes under Varying σ_M and AI Cost C

σ_M | C = 0.5 (Low) | C = 1.0 (Medium) | C = 2.0 (High) |

0.5 | Automation marginal | No automation | No automation |

1.0 | Moderate automation | Low automation | No automation |

1.5 | Extensive automation | Moderate automation | Marginal automation |

2.0 | Full replacement | Extensive automation | Moderate automation |

This shows that both technological feasibility (σ) and economic viability (C) jointly determine automation outcomes. Policies that increase AI development costs—e.g., AI taxes—or lower retraining costs can shift equilibria toward more balanced employment structures.

3.3. Empirical Illustration: Case Study of Shein

Shein, a Chinese ultra-fast fashion platform, provides an illustrative case of how AI adoption can affect labor distribution. It utilizes:

• AI-driven demand prediction to determine fashion trends.

• A glocalized supply chain, relying on small-scale domestic producers with agile response cycles.

Labor impact:

• Middle-skill roles in pattern-making, order processing, and logistics are increasingly automated.

• Low-skill workers remain critical in packaging and flexible manufacturing.

• High-skill labor in data science and fashion forecasting is rapidly expanding.

Shein's model reflects the logic of the game-theoretic model: given high σ_M, the firm automates these tasks but retains low-skill tasks due to lower elasticity.

3.4. Empirical Illustration: Case Study of Amazon

Amazon provides a contrasting example with a heavy investment in robotics and fulfillment center AI.

• Warehouse picking robots and automated logistics scheduling have displaced large segments of middle-skill logistical staff.

• High-skill AI engineers are essential to algorithm design and maintenance.

• Low-skill workers continue to perform last-mile delivery and customer service.

Amazon's extensive use of AI for inventory management, predictive shipping, and customer profiling illustrates the capital-intensive strategy of large firms. Labor polarization is clearly visible in the reduction of mid-tier management and operational staff, and expansion of both top-tier engineers and bottom-tier logistics workers.

3.5. Policy Implications of Simulation

The simulation results suggest several policy takeaways:

1. Targeted retraining programs should focus on transitioning displaced middle-skill workers to low-barrier high-skill positions (e.g., tech support, data annotation).

2. AI taxation or adoption caps may reduce incentives to fully automate highly substitutable occupations.

3. Incentives for human-AI complementarity (e.g., co-bot design, hybrid systems) can reduce labor displacement.

These insights build on the model’s formal logic to generate actionable guidance for policymakers and corporate strategists.

4. Model Analysis and Results

4.1. Equilibrium Conditions

• If σ_M is high, AI adoption becomes dominant for the firm.

• High-skill labor is retained, as its tasks are complementary to AI.

• Low-skill labor sees mixed effects—partial displacement or wage suppression.

• Middle-skill jobs are automated aggressively, reducing demand drastically.

4.2. Polarization Outcome

The model predicts that under high substitution elasticity for middle-skill labor:

• Wages for M fall, or jobs are eliminated.

• H wages rise, due to complementarities with AI.

• L employment becomes more prevalent, though under wage pressure. This mirrors real-world patterns of labor market polarization.

5. Discussion

The model provides a formal structure for understanding how technological adoption decisions are shaped not only by cost-benefit analyses, but also by task-level characteristics of labor. It supports the empirical claim that routine-intensive, middle-skill jobs are most at risk (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020), and adds strategic insight into firm behavior.

Implications:

• Education and training policy must focus on either high-skill upskilling or protecting low-skill service work.

• Wage subsidies or tax credits could incentivize firms to retain human workers in partially substitutable roles.

• Dynamic regulation of AI deployment based on sectoral elasticity could mitigate the polarization trajectory.

6. Conclusion

This paper presents a novel game-theoretic framework to explain how AI adoption leads to labor market polarization. By incorporating occupational substitution elasticity, we show that firms strategically displace labor where replacement is easiest—middle-skill jobs—while retaining high-skill complements and low-skill manual labor. The theoretical findings align with global trends and offer actionable insights for managing the future of work in an AI-driven economy.

References

[1]. Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. Handbook of Labor Economics, 4, 1043–1171.

[2]. Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019). Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 3–30.

[3]. Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2020). Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. Journal of Political Economy, 128(6), 2188–2244.

[4]. Autor, D., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333.

[5]. Autor, D., & Dorn, D. (2013). The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553–1597.

[6]. Benzell, S. G., Kotlikoff, L., LaGarda, G., & Sachs, J. (2015). Robots are us: Some economics of human replacement. NBER Working Paper No. 20941.

[7]. Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age. W. W. Norton.

[8]. Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., & Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4), 655–683.

[9]. Frey, C., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280.

[10]. Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2014). Explaining job polarization. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2509–2526.

[11]. Graetz, G., & Michaels, G. (2018). Robots at work. Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(5), 753–768.

[12]. Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

[13]. Kaplan, J. (2015). Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

[14]. Mokyr, J., Vickers, C., & Ziebarth, N. (2015). The history of technological anxiety and the future of economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 31–50.

[15]. Nedelkoska, L., & Quintini, G. (2018). Automation, skills use and training. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202.

[16]. Restrepo, P. (2022). The race between man and machine: Implications of technology for growth, factor shares, and employment. Review of Economic Dynamics, 44, 1–35.

[17]. Spence, M. (1977). Entry, capacity, investment and oligopolistic pricing. Bell Journal of Economics, 8(2), 534–544.

[18]. Vives, X. (1999). Oligopoly Pricing: Old Ideas and New Tools. MIT Press.

[19]. World Economic Forum. (2023). Future of Jobs Report.

[20]. Zilibotti, F. (2017). Growing and slowing down like China. Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(5), 943–988.

[21]. Zhang, L., & Zeng, Z. (2022). AI, labor substitution, and wage inequality: A task-based approach. China Economic Review, 72, 101733.

Cite this article

Li,C. (2025). AI Adoption and Labor Market Polarization: A Game-Theoretic Model Based on Occupational Substitution Elasticity. Journal of Economic and Managerial Dynamics,1(1),24-31.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Economic and Managerial Dynamics

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. Handbook of Labor Economics, 4, 1043–1171.

[2]. Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019). Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 3–30.

[3]. Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2020). Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. Journal of Political Economy, 128(6), 2188–2244.

[4]. Autor, D., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333.

[5]. Autor, D., & Dorn, D. (2013). The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553–1597.

[6]. Benzell, S. G., Kotlikoff, L., LaGarda, G., & Sachs, J. (2015). Robots are us: Some economics of human replacement. NBER Working Paper No. 20941.

[7]. Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age. W. W. Norton.

[8]. Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., & Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4), 655–683.

[9]. Frey, C., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280.

[10]. Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2014). Explaining job polarization. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2509–2526.

[11]. Graetz, G., & Michaels, G. (2018). Robots at work. Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(5), 753–768.

[12]. Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

[13]. Kaplan, J. (2015). Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

[14]. Mokyr, J., Vickers, C., & Ziebarth, N. (2015). The history of technological anxiety and the future of economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 31–50.

[15]. Nedelkoska, L., & Quintini, G. (2018). Automation, skills use and training. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202.

[16]. Restrepo, P. (2022). The race between man and machine: Implications of technology for growth, factor shares, and employment. Review of Economic Dynamics, 44, 1–35.

[17]. Spence, M. (1977). Entry, capacity, investment and oligopolistic pricing. Bell Journal of Economics, 8(2), 534–544.

[18]. Vives, X. (1999). Oligopoly Pricing: Old Ideas and New Tools. MIT Press.

[19]. World Economic Forum. (2023). Future of Jobs Report.

[20]. Zilibotti, F. (2017). Growing and slowing down like China. Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(5), 943–988.

[21]. Zhang, L., & Zeng, Z. (2022). AI, labor substitution, and wage inequality: A task-based approach. China Economic Review, 72, 101733.