1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis is a chronic degenerative joint disease that causes knee pain and movement disorders in patients. According to the World Health Organization, about 355 million people suffer from osteoarthritis worldwide. The prevalence of osteoarthritis is 10% - 17% in people over 40 years old, 50% over 60, and 80% in those over 75. An early sign of OA is knee cartilage degeneration. Recent studies have shown that knee osteoarthritis is reversible if found in early stages of the biochemical changes in knee articular cartilage. In order to diagnose OA, doctors must confirm symptoms such as cartilage loss just as mentioned before. As a result, it is very important to monitor the volume of the cartilage. The traditional method for image-based knee cartilage assessment is having MRI images annotated by humans’ slice by slice. This process is very time-consuming and labor-intensive. Meanwhile, manual annotation is also prone to errors caused by subjective factors of personnel. Regardless, manual segmentation results is still the gold standard reference for deep learning segmentation algorithms [1].

At present, With the continuous development of artificial intelligence, people have tried to use deep learning and convolutional neural networks to segment images to achieve the effect of reducing the workload of doctors. The use of deep learning for image processing has become the current mainstream, and medical image segmentation has also become a successful example of deep learning application in the field of image processing with its unique application scenarios [2]. However, there are only 2D models after image segmentation, so the doctors cannot have an accurate and reproducible volumetric quantification of articular cartilage in the knee, and they cannot diagnose the condition of the knee joint precisely.

To solve this problem, we propose a 3D model combining three individual 2D networks to perform segmentation efficiently and accurately; Also, doctors can have an accurate volumetric quantification of the knee joint through the 3D model.

2. Review work

There have been many researches on image segmentation. This section elaborates on some image segmentation frameworks developed from the past to the present. TABLE 1 shows some common frameworks and describe their features and pros and cons.

|

Frameworks |

Features |

Notes |

|

FCN |

Dense prediction, pixel-level segmentation |

Duplicate convolutional calculations caused by overlapping image blocks are avoided |

|

DeconvNet |

Multiple deconvolutional layers and depooling layers are designed |

Solved the size problem in the original FCN network, making the detailed information of the object more detailed |

|

DeepLab |

The convolutional neural network is fused with the traditional probability graph model and uses empty convolution |

Enlargement of the receptive field without evolutionary pooling prevents the loss of local information features of the image |

|

SegNet |

A maximum value pooled index method is proposed |

The information lost during pooling can be obtained during the decoding phase by the maximum value index |

|

PSPNet |

A pyramid model is proposed to extract multi-scale information features of images |

The fusion of detailed features and global features greatly enriches the semantic information of the image |

|

U-Net |

The codec network structure of hop splicing is used for feature fusion |

The impact is far-reaching, and the U-Net network is widely used |

|

... ... |

... ... |

... ... |

3. Material and methods

3.1. Network structure

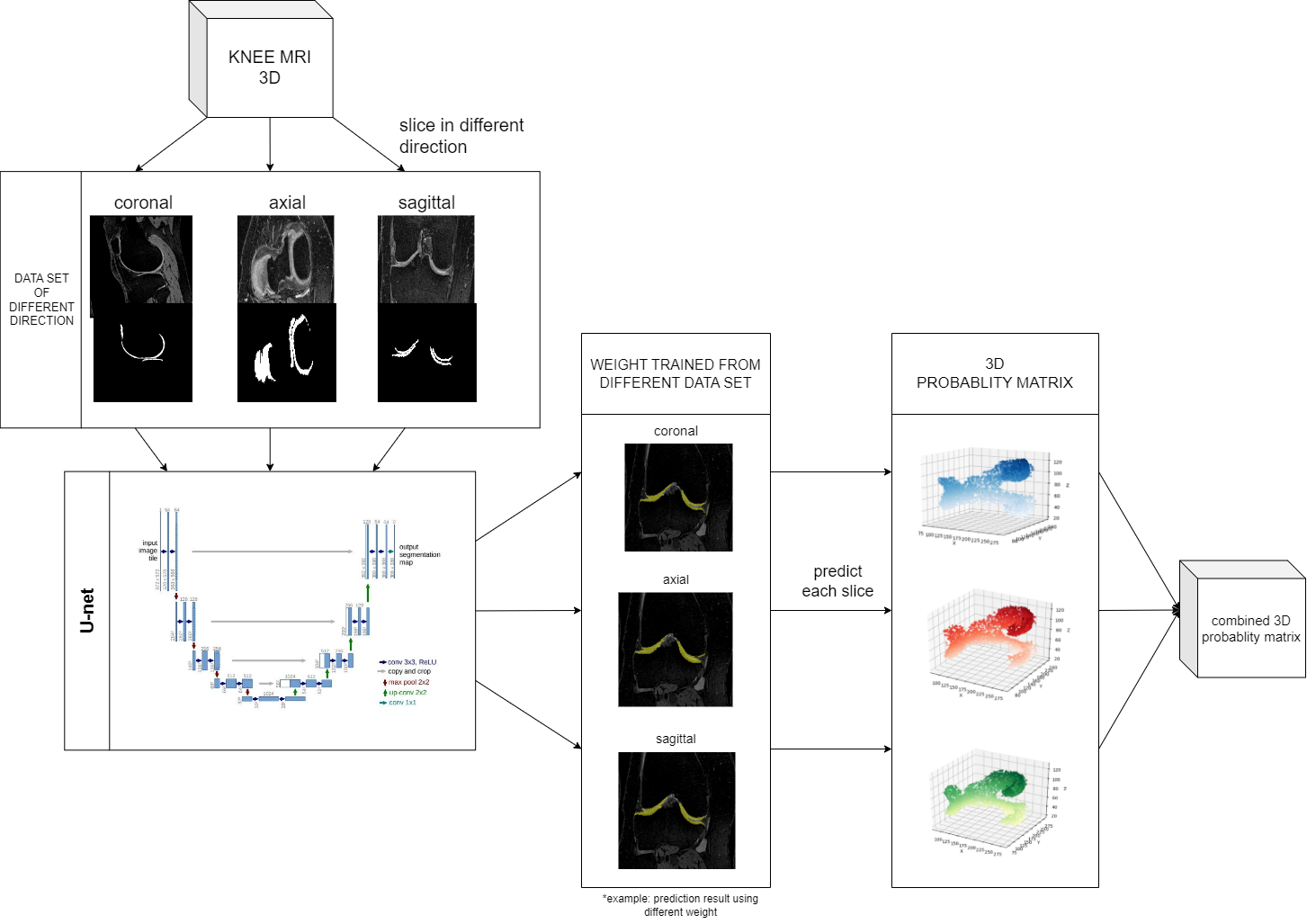

In recent years, U-Net, as a fully convolutional network, has been the most common approach for medical image segmentation. However, existing 2D U-Net models can only analyze images from a single orientation, making it challenging to capture information from different anatomical planes. To address this limitation, we extended the U-Net to 3D by combining three orientation-based 2D U-Nets in the axial, coronal, and sagittal orientations. Using this approach, we obtained predictions from three different orientations, and then weighted and combined these predictions to derive the optimal weights. This allowed us to gather information from multiple anatomical planes and improve the accuracy of our segmentation. The flow diagram for our algorithm is illustrated in Fig 1.

The U-Net architecture used in this study is a convolutional neural network composed of a Contracting Path for feature extraction and an Expansive Path for segmentation. The Contracting Path involves repeated 3x3 convolutions with ReLU activations and 2x2 max-pooling for down-sampling. The Expansive Path performs up-sampling, and each step includes up-convolution, feature concatenation, and additional convolutions. A 1x1 convolution at the final layer maps feature vectors to the desired output classes. This network utilizes VGG16 as the main feature extraction backbone, facilitating the use of pre-trained weights. All three networks share the same structure and parameter value. They use Adam optimizer with maximum learning rate of

| Parameter | Value |

| Backbone | VGG16 + Unet |

| Batch size | 2 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| ƞ | 1E-04 |

| β1 | 0.9 |

| β2 | 0.999 |

| ϵ | 1E-08 |

| Weight initialization | Pre-train |

| Activation | Softmax |

| Loss | Soft Dice |

3.2. Dataset and dataset processing

In this study, the dataset consisting of three-dimensional knee MRI from 88 retrospective patients at two time points (baseline and 1-year follow-up) with ground truth articular cartilage segmentations was standardized. The original data, stored with a DICOM format, are of 384*384*160 pixels each image.

The original data is stored in a DICOM format. Since the U-Net model we choose to use can only be trained in 2 dimensions, we must transform three-dimensional MRI DICOM files into two-dimensional images for training as shown in figure 1. Each knee has 160 slices in coronal direction and 192 slices in axial and sagittal direction. So, the number of the slices is 5120 in coronal direct, and 6144 in axial and sagittal direct. This dataset contains labeled images with corresponding ground truth segmentation masks. The MRI image is transformed from DICOM format into a PNG format image, which is of 384*384 (or 384*160) pixels per slice.

3.3. Training

The ultimate goal for this research is to create a model that takes three multi-channel 2D image slices of

To begin the training process, a pre-trained U-Net model is employed as the backbone architecture. This model has been previously trained on a large dataset to capture general image features. And then we replace the weight of the model with new weight to accommodate the cartilage segmentation task during the training.

To optimize training, this study employed a dynamic learning rate scheduler. The learning rate is adjusted during training epochs, enabling the network to efficiently navigate the optimization landscape.

To improve efficiency, this study trained three directions on three computers at the same time and sent the results of the three directions to one computer after the training [3].

3.4. Combination and evaluation

We apply the models to their corresponding testing dataset and obtain the cartilage probability of each pixel. For example, if the model is trained to predict dataset sliced along coronal. The probability data is stored as two-dimensional matrix, represented as

Next, we combine the three matrixes through linear blending at the weight of

To further analyze and compare the performance of different models, we conducted dice coefficient analysis on the predicted probability matrix

4. Results

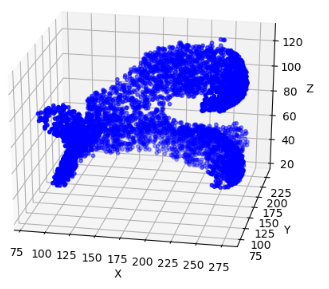

The three deep learning models are trained to their best performance on three different datasets, with their MIOU being 83.54%, 77.93% and 72.85% respectively. After piling up each slice, the cartilage distribution in 3D space is shown in Figure 2.

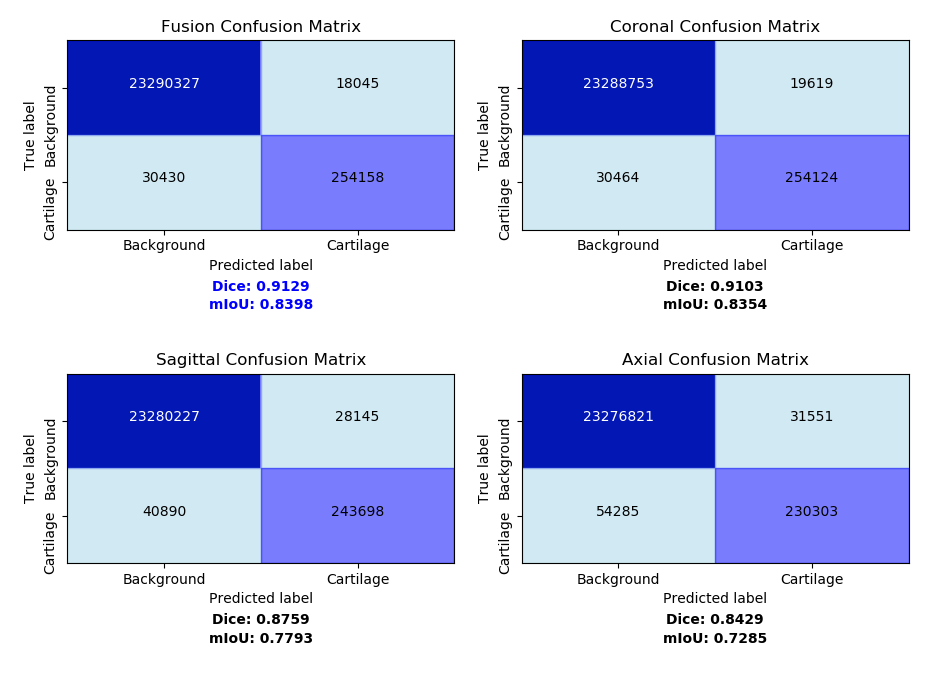

The final fusion model is a linear blending of the prediction values using the weights of (0.5077, 0.4012, 0.0911). This linear blending weight should be slightly altered to fit different models. After applying each model to 3D MRI images, we conducted further analysis using evaluation metrics including confusion Matrix and dice coefficient. The discrepancy between predicted probability and ground truth matrix of the four model can be shown using confusion matrixes. Dice coefficient is introduced for a clearer accuracy measurement in 3D space. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

We can tell from the table that the fusion model predicts the highest number of accurate cartilage pixels with 254,158 and the lowest number of wrong cartilage pixels with 18045. Fusion model achieves the highest dice coefficient at 0.9129, slightly surpassing the coronal plane model at 0.9103, overwhelming the sagittal plane model at 0.8759 and axial plane model at 0.8429. This shows the fusion model has less miss-typed pixel and achieves higher accuracy than all the individual plane models [4].

5. Disscussion

All three individual plane models are expected to achieve the same accuracy. However, we can't find good explanation for the bad performance of axial plane model. Why the dice coefficient of axial plane model is so much lower than the other two needs further discussion. The problem may lie in the original data set, or the structure of the cartilage itself. That is the assumption that certain planes of the cartilage just don't give good features for neural network to learn. Therefore, when doing linear blend, weight of these planes should be reduced modestly.

In this paper, our 3D segmentation model is actually a combination of three 2D segmentation models. The original intention is to make up the connection between different planes that the individual 2D model is likely to ignore. If the models are from multiple axes than three, the accuracy of the final fusion model is expected to improved. Moreover, there are now 3D U-net model that does 3D convolution to the MRI image. This allows the network to study the connection between plane while training, but requires a large more effort to train. Further research can compare the pros and cons of different segmentation method [5].

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of deep learning algorithms in accurately performing segmentation on knee MRI images for the early detection of knee osteoarthritis. By utilizing a U-Net model and combining three individual 2D networks, the researchers were able to achieve efficient and accurate segmentation of medical images, reducing the workload of doctors and providing an accurate volumetric quantification of articular cartilage in the knee. The fusion model, in particular, outperformed the individual plane models, with a dice coefficient of 0.9129, indicating higher accuracy. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, such as the need for a larger dataset and further research to understand the discrepancies in model performance. Overall, the findings highlight the potential of deep learning and segmentation algorithms in aiding the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis and suggest further exploration in this field.

7. Acknowledgements

Bowen Luan, Keran Xu, Liyuan Zhou, Yaxing Zhang and Jiayu Jin contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors. The authors would like to thank all colleagues and students who contributed to this study.

References

[1]. H.S. Gan, M.H. Ramlee, A.A. Wahab, et al. "From classical to deep learning: review on cartilage and bone segmentation techniques in knee osteoarthritis research." Artificial Intelligence Review (2020): 1-50.

[2]. S. Gaj, M. Yang, K. Nakamura, et al. "Automated cartilage and meniscus segmentation of knee MRI with conditional generative adversarial networks." Magnetic resonance in medicine 84.1 (2020): 437-449.

[3]. O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, T. Brox. "U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation." International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, Cham, 2015.

[4]. Desai AD, Caliva F, Iriondo C, Mortazi A, Jambawalikar S, Bagci U, Perslev M, Igel C, Dam EB, Gaj S, Yang M, Li X, Deniz CM, Juras V, Regatte R, Gold GE, Hargreaves BA, Pedoia V, Chaudhari AS; IWOAI Segmentation Challenge Writing Group. The International Workshop on Osteoarthritis Imaging Knee MRI Segmentation Challenge: A Multi-Institute Evaluation and Analysis Framework on a Standardized Dataset. Radiol Artif Intell. 2021 Feb 10; 3(3): e200078. doi: 10.1148/ryai.2021200078. PMID: 34235438; PMCID: PMC8231759.

[5]. Perslev, M., Dam, E.B., Pai, A., & Igel, C. (2019). One Network to Segment Them All: A General, Lightweight System for Accurate 3D Medical Image Segmentation. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention.

Cite this article

Luan,B.;Xu,K.;Zhou,L.;Zhang,Y.;Jin,J. (2025). Imaging Knee MRI Segmentation and 3D Reconstruction Based on Deep Learning. Applied and Computational Engineering,199,1-7.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of CONF-SEML 2025 Symposium: Machine Learning Theory and Applications

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. H.S. Gan, M.H. Ramlee, A.A. Wahab, et al. "From classical to deep learning: review on cartilage and bone segmentation techniques in knee osteoarthritis research." Artificial Intelligence Review (2020): 1-50.

[2]. S. Gaj, M. Yang, K. Nakamura, et al. "Automated cartilage and meniscus segmentation of knee MRI with conditional generative adversarial networks." Magnetic resonance in medicine 84.1 (2020): 437-449.

[3]. O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, T. Brox. "U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation." International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, Cham, 2015.

[4]. Desai AD, Caliva F, Iriondo C, Mortazi A, Jambawalikar S, Bagci U, Perslev M, Igel C, Dam EB, Gaj S, Yang M, Li X, Deniz CM, Juras V, Regatte R, Gold GE, Hargreaves BA, Pedoia V, Chaudhari AS; IWOAI Segmentation Challenge Writing Group. The International Workshop on Osteoarthritis Imaging Knee MRI Segmentation Challenge: A Multi-Institute Evaluation and Analysis Framework on a Standardized Dataset. Radiol Artif Intell. 2021 Feb 10; 3(3): e200078. doi: 10.1148/ryai.2021200078. PMID: 34235438; PMCID: PMC8231759.

[5]. Perslev, M., Dam, E.B., Pai, A., & Igel, C. (2019). One Network to Segment Them All: A General, Lightweight System for Accurate 3D Medical Image Segmentation. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention.