1. Introduction

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) acquires brain signals, analyzes them, and translates them into commands sent to output devices to carry out desired actions [1]. One of the main limitations of traditional eye prosthetics is their inability to achieve a full range of natural eye movements [2]. These prosthetics are typically static or purely cosmetic, lacking the ability to mimic the natural range of motion and coordination of a real eye. As a result, they do not provide any functional benefits such as tracking or focusing on objects, which are critical for visual interaction.

In response to these challenges, the development of BCI has emerged as a promising innovation in the field. The development of the P300 Speller intends to remove limitations of existing eye prosthetics by detecting the steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP) in the occipital cortex and various other signals, thus replicating the dynamics of natural eye movement [3]. BCI offers a closer approximation of natural eye function through these approaches.

This review of the literature aims to explore the current state of research on BCI sprockets, such as the P300 sprocket [1], sprockets based on SSVEP [4], sprockets based on motor imaging [5] and age-related data differences [6]. These approaches are crucial in addressing concerns about their application in various fields, including ocular motility disorders and advanced eye prosthetics [2]. As brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are being adapted for ocular applications, exploring their potential in ocular prosthetics can lead to more effective treatments and innovations [5]. A more comprehensive understanding of BCI technology, especially its role in neuroprosthetics, is essential for advancing future clinical applications and furthering research in this domain.

1.1. P300 speller

Detecting event-related potentials (ERPs) is important for developing a brain-computer interface (BCI), an example of an ERP-based BCI is the P300 speller, which enables users to spell characters. The P300 speller leverages the P300 wave, an ERP generated using the oddball paradigm. This paradigm presents random visual stimuli that elicit a surprise effect in the subject. Farwell and Donchin first proposed the P300 alphabet speller system, which is displayed on a computer screen as a 6×6 matrix containing all the available characters. During use, the user focuses on the desired character, and when the matrix cell containing that character is intensified, a P300 wave (a positive voltage deflection occurring approximately 300 ms after stimulus onset) is detected using a stepwise linear discriminant analysis (SWLDA) algorithm [7].

There are various ways of detecting P300 and these ways are created to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the BCI system, some famous examples include ICA (Independent Component Analysis), CSP (Common Spatial Pattern), HDCA (Hierarchical Discriminant Component Analysis), and CNN (Convolutional Neural Network). To elicit ERPs, the rows and columns of the matrix are randomly intensified. Each character’s intensification is repeated multiple times, known as epochs. Initially designed for Latin characters, recent advancements have extended the P300 speller to Chinese characters [8]. Improvements in the P300 speller have largely focused on signal processing and detection techniques, such as support vector machines, neural networks, and Bayesian linear discriminant analysis.

Despite these advancements, the graphical user interface of the P300 speller has remained relatively unchanged for over two decades. Townsend et al. proposed an alternative paradigm to the traditional row/column paradigm (RCP), the checker-board paradigm (CBP), which utilizes two checkerboards to mitigate confusion near the target [7]. As shown in Table 1, in a study involving 18 participants using an 8×9 matrix of alphanumeric characters and keyboard commands, the CBP achieved a mean online accuracy of 92%, outperforming the RCP’s 77%. The CBP also had a higher mean information bit rate of 23.17 bits per minute (bpm) compared to 19.85 bpm for the RCP. Research on the P300 speller focuses on improving reliability over time and across subjects and enhancing the information transfer rate. However, some researchers believe further improvements should come from application-oriented P300 spellers, incorporating features like word completion, prediction, and vocabulary knowledge.

|

Participant |

RC sequences |

CB sequences |

RC accuracy |

CB accuracy |

RC (sel/min) |

CB (sel/min) |

RC bit rate |

CB bit rate |

|

1 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

100.00 |

94.74 |

4.28 |

4.31 |

26.38 |

23.94 |

|

2 |

5.00 |

4.00 |

55.26 |

89.47 |

4.28 |

3.89 |

10.38 |

19.62 |

|

3 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

92.11 |

89.47 |

6.13 |

6.38 |

32.42 |

32.12 |

|

4 |

5.00 |

4.00 |

71.05 |

89.47 |

4.28 |

3.89 |

15.06 |

19.62 |

|

5 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

71.05 |

86.84 |

4.28 |

4.84 |

15.06 |

23.21 |

|

6 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

94.74 |

89.47 |

5.04 |

4.31 |

27.96 |

21.73 |

|

7 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

97.37 |

100.00 |

5.04 |

4.31 |

29.39 |

26.62 |

|

8 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

89.47 |

89.47 |

5.04 |

3.89 |

25.38 |

19.62 |

|

9 |

5.00 |

4.50 |

50.00 |

86.84 |

4.28 |

3.55 |

8.96 |

17.03 |

|

10 |

5.00 |

4.00 |

44.74 |

97.37 |

4.28 |

3.89 |

7.61 |

22.71 |

|

11 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

65.79 |

92.11 |

5.04 |

3.89 |

15.82 |

20.58 |

|

12 |

5.00 |

2.50 |

63.16 |

94.74 |

4.28 |

5.50 |

12.63 |

30.52 |

|

13 |

5.00 |

4.50 |

47.37 |

89.47 |

4.28 |

3.55 |

8.27 |

17.87 |

|

14 |

4.00 |

2.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

5.04 |

6.38 |

31.09 |

39.35 |

|

15 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

92.11 |

100.00 |

5.04 |

4.31 |

26.63 |

26.62 |

|

16 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

86.84 |

81.58 |

4.28 |

3.26 |

20.52 |

14.17 |

|

17 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

86.84 |

92.11 |

5.04 |

4.84 |

24.18 |

25.56 |

|

18 |

5.00 |

4.50 |

84.21 |

84.21 |

4.28 |

3.55 |

19.54 |

16.22 |

|

Mean |

4.50 |

3.61 |

77.34 |

91.52 |

4.68 |

4.36 |

19.85 |

23.17 |

Current P300 spellers are not yet ready for widespread commercial or clinical use due to issues with robustness and user interface adaptability. However, exceptions exist, such as a P300 speller developed by the Wolpaw lab, which a late stage ALS patient successfully used at home. The French National Research Agency’s RoBIK (Robust BCI Keyboard) project (Mayaud) aims to develop efficient, user-friendly BCIs for daily use by non-technical staff, such as nurses [9]. The intendiX solution, proposed by g.tec in 2009, is designed to be operated by caregivers or patients’ families at home. This BCI uses visually evoked EEG potentials (VEP/P300) and features a 5×10 matrix. It allows users to select characters by focusing on them for several seconds. Unlike the traditional P300 speller, the intendiX system can detect the idling state and only selects characters when the user pays attention. It also enables users to trigger alarms, speak written text, print or email text, and send commands to external devices. This system includes all necessary components, such as software, amplifiers, and caps.

1.2. Spellers based on SSVEP

|

Without disabilities |

With disabilities |

||||

|

Acc. (%) |

ITR (bpm) |

Acc. (%) |

ITR (bpm) |

||

|

Min |

75.00 |

3.64 |

81.52 |

12.08 |

|

|

Max |

100.00 |

40.68 |

98.82 |

32.77 |

|

|

Mean |

93.73 |

22.88 |

87.94 |

18.09 |

|

|

S.D |

6.47 |

9.82 |

7.36 |

7.39 |

|

The steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP), or frequency visual evoked potential (f-VEP), is a brain signal recorded from the occipital cortex in response to a periodically flickering visual stimulus. This brain signal is characterized by oscillations at the same frequency as the flickering visual stimulus. When the visual stimulus flickers at a sufficiently high rate, typically starting from around 6 Hz, the individual evoked responses to each stimulus flash overlap [4]. When visual stimuli flicker at certain rates, the brain’s response becomes synchronized with that stimulus. Not only does the response peak at the same frequency as the stimulus but there are also peaks at integer multiples of that frequency. This makes the steady-state visual evoked potential, or SSVEP, ideal for use with a brain-computer interface (BCI). The user has to do very little to generate a recognizable brain signal, which is not to say that the BCI is easy to construct. In fact, the SSVEP’s simplicity and usefulness are underscored by the many different ways frequency coding can be implemented.

The SSVEP-based BCI operates from the basis of the cortical magnification theory, which states that a large part of the visual cortex processes the central visual field. This theory accounts for our observing and knowing that visual processing happens much better in the central field of vision than in the periphery. It goes a long way toward explaining why the SSVEP response gets bigger the closer we get to having visual stimuli in the central field (not counting what happens with the SSVEP response as we vary in focusing on different visual frequencies). Following the aforementioned commandsto-frequencies-to-commands principle, we can now use an SSVEP-based BCI to get distinct commands by focusing on varying visual frequencies.

The application of SSVEP-based BCIs extends into many areas, including neuroprosthetic device control and the restoration of grasping functions in people with spinal cord injuries. Their standard configuration contains a central fixation point and five command boxes that flicker at the very edges of the screen. This design minimizes the need for users to shift their gaze significantly.

Visually represented by Table 2, in an assessment task conducted using the SSVEP-based Bremen-BCI system, Ivan Volosyak et al. tested its ability to spell out five messages. For each subject capable of using the speller, the system achieved an average accuracy of 93.73% and an information transfer rate of 22.88 bits per minute (bpm) for individuals above 18 years old with no disabilities [10].

1.3. Spellers based on motor imagery

Motor imagery BCIs use a limited number of commands, typically involving imagined movements such as left or right-hand movements. The Berlin BCI (BBCI) speller, known as Hex-o-Spell, was developed by the Fraunhofer FIRST (IDA) in Berlin [11]. This is an EEG-based system that relies on detecting spatio-spectral changes during various motor imagery tasks. By utilizing machine learning techniques, the system quickly adapts to the unique brain patterns of each user, providing high-quality feedback even in the first session. The Hex-o-Spell system adapts modern dynamic text entry methods to create a BCI-compatible mental text entry solution. Hex-o-Spell draws inspiration from the Hex system, originally designed for mobile devices equipped with accelerometers. In the original Hex system, users navigated a hexagonal grid by tilting the device. The system adjusted its response dynamics, making frequently used actions easier while preserving the optimal path for any word sequence. This design aimed to provide stability in the letter generation process, allowing users to transition from closed-loop to open-loop control gradually. The asynchronous BCI speller allows users to write 29 characters and execute the backspace command using imagined right-hand and foot movements. The interface features six hexagonal fields surrounding a circle, with an arrow used for character selection.

The BBCI was tested on two subjects at the CeBIT fair in 2006, achieving writing speeds ranging from 2.3 to 7.6 characters per minute, with error-free, completed sentences [12].

1.4. Age-related data differences (concerns of application)

The potential of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) for use in elderly patients is enormous, but little of the current research is directly applicable to this population. Most BCI investigations focus on younger test subjects, though we know that neural response patterns tend to differ with age. If we want to determine the suitability of BCIs for use with older adults, it is imperative to study and understand these neural response variations and what they mean for future BCI results.

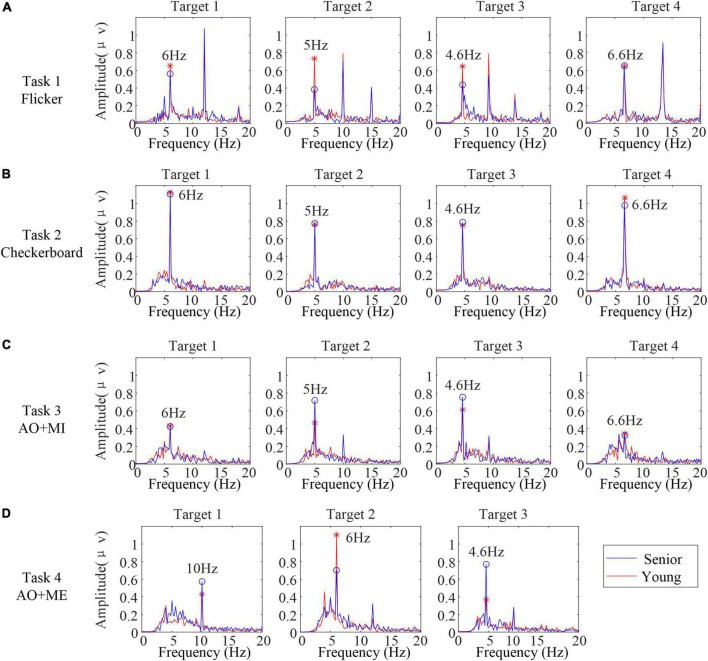

To investigate this systemic deficiency, X. Zhang et al. conducted a study that pitted the young against the old. They looked at two groups: 22to 30-year-olds and 60to 75-yearolds. When the researchers compared the groups, they found that older adults had much larger P1 amplitudes for motion onset compared to their younger counterparts. In other words, seniors seem to see movement better than younger adults. And this, of course, has implications for BCIs that use motion to elicit a response. Seeing is one thing, but understanding or making a decision based on what you’re seeing is another. If older adults can see motion better, as per the findings of the study, then mVEP-based BCIs may be better suited for them than for younger adults.

The research evaluated how well different kinds of visual stimuli—like flickering lights and moving checkerboards—worked to induce brain responses as measured by EEG in older adults. The team looked not just at what kind of response was evoked when a stimulus was presented, but also at how well the EEG responses could be “tuned in” to the specific kind of visual signal being seen. They found that older adults had better ”tuning in” for some visual signals than younger adults, especially with the light flickering signal.

In steady-state response analysis, SSVEP and SSMVEP were successfully obtained in both age groups. However, the canonical correlation analysis (CCA) accuracies for SSVEPs/SSMVEPs in the senior group were slightly lower than in the younger group in most cases as indicated by Figure 1, Using an extended CCA-based method significantly improved performance for both groups. However, the accuracy improvement for AO targets was less pronounced in the senior group, increasing from 63.1% to 71.9%, compared to an improvement from 63.6% to 83.6% in the younger group.

These findings suggest that the mVEP characteristics in senior subjects may provide a valuable signal modality for designing BCIs tailored to the senior population. Furthermore, the steady-state response, particularly SSVEP/SSMVEP, offers a robust way to determine visual target selection. However, the reduced improvement in accuracy for AO stimuli in the senior group highlights the need for further refinements in algorithm design. The study emphasizes the importance of considering age-related variations when designing BCIs aimed at addressing age-related conditions, such as macular degeneration [6].

1.5. Creating images using signals

Deep learning methods can effectively classify motor imagery (MI) EEG signals but typically require 2D image or feature inputs rather than 1D time series signals. To address this limitation, researchers have explored converting MI-EEG signals into 2D representations using time-frequency analysis methods like continuous wavelet transform (CWT) and shorttime Fourier transform (STFT). These techniques generate 2D scalograms or spectrograms that can be used as inputs to convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Some studies have shown promising results by applying CNN architectures such as AlexNet and LeNet to classify MI-EEG signals transformed into 2D images. However, the time-varying nature of EEG frequency bands can still pose challenges, potentially limiting performance.

To overcome data scarcity in MI-EEG datasets, transfer learning has been explored. Pre-trained CNN models can be fine-tuned on the target task, enabling the extraction of richer features and improving classification accuracy when training data is limited. C¸ ag˘atay Murat Yılmaz et al. propose a novel signal-to-image conversion method using quasi-probabilistic distribution models as an alternative to STFT and CWT. This method is then combined with pre-trained CNN models like AlexNet, GoogLeNet, and SqueezeNet, as well as an ensemble approach using hard voting, for classifying the new MI-EEG image representations.

|

Subjects |

Accuracy |

Kappa |

|||||

|

CWT+CNN |

Modular Network |

CSE-UAEL+C-3 |

Hard Voting of pre-trained CNNs |

CWT+CNN |

Modular Network |

Hard Voting of pre-trained CNNs |

|

|

A01 |

83.4 |

84.91 |

91.67 |

80.00 |

0.88 |

0.68 |

0.53 |

|

A02 |

83.8 |

66.38 |

63.89 |

82.96 |

0.73 |

0.36 |

0.62 |

|

A03 |

95 |

84.74 |

94.44 |

94.81 |

0.67 |

0.69 |

0.89 |

|

A04 |

85.4 |

81.36 |

72.22 |

86.67 |

0.73 |

0.62 |

0.66 |

|

A05 |

79.1 |

79.22 |

77.08 |

80.77 |

0.90 |

0.66 |

0.60 |

|

A06 |

86.7 |

70.67 |

75.69 |

84.55 |

0.71 |

0.45 |

0.69 |

|

A07 |

86.4 |

86.12 |

73.61 |

77.78 |

0.58 |

0.71 |

0.54 |

|

A08 |

94 |

83.81 |

94.44 |

79.23 |

0.90 |

0.72 |

0.56 |

|

A09 |

94.8 |

83.04 |

90.28 |

90.83 |

0.68 |

0.66 |

0.82 |

|

Avg±Std |

87.6±5.7 |

80.03±6.52 |

81.48±11.33 |

84.18±5.37 |

0.75±0.11 |

0.61±0.12 |

0.66±0.12 |

The proposed approach of using hard voting to ensemble the outputs of pre-trained CNN models (AlexNet, GoogLeNet, SqueezeNet) demonstrated improved classification performance compared to previous studies. Table 3 shows, for subject A04, the average classification accuracy increased from 85.4% (CWT+CNN) to 86.67%, and for subject A05, it increased from 79.22% (modular network) to 80.77%. A similar trend was observed for the kappa statistic, with significant improvements noted for subject A03 (from 0.69 to 0.89) and subject A09 (from 0.68 to 0.82) [12].

These results highlight that the proposed signal-to-image conversion method, combined with an ensemble of pre-trained CNNs, can outperform earlier approaches in classifying motor imagery EEG signals. The method’s effectiveness is particularly notable for the subjects mentioned, demonstrating its potential for advancing MI-EEG classification techniques.

2. Method/analysis

A structured and systematic approach was employed to gather the referenced articles on brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), motor imagery EEG (MI-EEG) signal classification, and neural prosthetics. The extent of the claim, “Recent publications,” is from 2019 to 2024. Fundamental research from an older period is examined for definitions and the origin of some methods analyzed. The search began with keyword based queries across several academic databases, including Nature, IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and ResearchGate, ensuring coverage of interdisciplinary studies in neuroscience, biomedical engineering, and artificial intelligence; keywords used included ’brain-computer interface’, ’motor imagery EEG’, ’neural prosthetics’, ’deep learning’, ’CNN-based classification’, ’RVSP BCI’, Boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT were incorporated to refine search results and filter out unrelated studies. For example, combinations such as ’motor imagery EEG AND deep learning AND classification’ were used to locate studies exploring advanced machine learning methods applied to MI-EEG signals for improved classification. Filters were applied to limit the results to studies published within the last five years to ensure the material reflected the latest technological and research developments in BCI and related fields.

Locating several of the databases required focused strategies. For the database Nature, I needed to find articles specifically related to research on human-centered designs for neuromorphic systems, as well as studies that dealt with the control of such systems using human brains. I used PubMed to locate research on EEG classification techniques and the types of brain signals that control prosthetic devices. For research on the application of machine learning to these types of problems, I used IEEE Xplore. I identified relevant articles like Ali et al. [6] and Wei et al. [13] that deal with the application of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transfer learning to enhance the accuracy of classifications of Movement Imagery EEG signals, a capability that’s vital for achieving real-time prosthetic control. This required looking at the reference lists of important articles to find more key studies—particularly impactful ones—that the original search didn’t yield. For example, Farina et al. [14] on neural prosthetics and Abiri et al. [15] on EEG-based brain computer interface paradigms were found this way. This tactic of reference mining, in tandem with an initial article sort, located several emergent and subfield studies. Wang et al. [16] on integrating haptic feedback into BCIs, for instance. And once we had the articles, we reviewed their abstracts. The emphasis was on reviewing studies that talked about machine learning, particularly convolutional neural networks and deep transfer learning, and the real-world application of BCIs, like prosthetics and assistive robots, that help impaired people achieve basic motor functions. Of course, many studies also talked about the basic science and engineering of how signals from the human brain can be converted into commands for computers and robots. The engineering problems being solved reflect highly innovative areas of research.

Alternative access methods, including Google Scholar and ResearchGate, were used for studies behind paywalls, and platforms where researchers often share preprints or full-text versions. ResearchGate proved useful for accessing early work on BCI paradigms, such as Blankertz [11], and more recent studies in the field.

By combining keyword-based searches, database-specific strategies, and the snowball method, I compiled a collection of articles that reviewed the application of BCI technologies such progress could be made in restoring the vision of the visually disabled population. The studies covered various topics, from machine learning-based signal classification to the practical implementation of neural prosthetics and assistive technology. This method ensured the collection was comprehensive, recent, and relevant to the ongoing developments in brain-computer interfaces, focusing on their potential applications in real-time control systems, neural rehabilitation, and assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities.

3. Discussion

|

Method |

Pros |

Cons |

|

P300 Speller |

- Detects event-related potentials (ERPs)like the P300 wave. - High accuracy with CBP (92%). - Useful for both Latin and Chinese characters. - Advanced signal processing techniques improve reliability. |

- User interface relatively issues. - Needs multiple intensification for accuracy. |

|

SSVEP Speller |

- Minimal user training required. - High information transfer rate (ITR). - Easy to use with frequency-coded stimuli. - Achieves high accuracy (93.73%) and ITR (22.88 bpm). |

• Flickering visual stimuli can be visually tiring for users. Slightly lower accuracy in senior groups compared to younger users. |

|

Motor Imagery BCI (Hex- o- Spell) |

- Uses imagined movements for control. - Adapts quickly to individual brain patterns. - Error-free sentence completion. - Tested with real users. |

• Lower character entry speed (2.3 to 7.6 characters per minute). • Requires significant mental effort for accurate control. |

In this study, I focused on the identification of the effects of visual stimuli on EEG signals by brain-computer interface (BCI) techniques. In particular, this paper focuses on how the brain-neuronal computer interaction for spelling applications can be realized based on EEG signals. I have summarized the mainstream technology routes so far, enumerated and compared these different technology routes, and roughly described their development process, application scenarios, and progress, in which table 4 provides a summary of the pros and cons of each method. These conclusions aim to provide useful insights for research in this field.

Among the brain responses currently used in non-invasive BCI, I find event-related potentials (ERP), steady-state evoked potentials (SSVEP), motor imagery (MI), or slow cortical potentials. These responses can be provoked by external stimuli, such as visual or auditory stimuli (e.g., P300, SSVEP) or not (e.g., motor imagery). The expected EEG drives classification to specific feature extraction methods [17,18]. Therefore, I discuss different recognition and spelling techniques, primarily regarding the detection methods of these potentials.

The P300 speller, introduced in 1988 by Farwell et al., enables users to spell characters and has shown potential as an effective communication device for individuals with severe disabilities [4]. The work by D.J. Krusienski et al. demonstrated that participants could achieve speed and accuracy suitable for real-world communication through the analysis of P300 signals [1]. Additionally, a late-stage ALS patient successfully used a P300 speller at home, as developed by the Wolpaw lab [1]. These developments suggest that the P300 speller is the closest to transitioning from laboratory research to industrial application [4,9].

Regarding Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEP), this paradigm is highly promising in practical BCI applications due to its high information transfer rate (ITR), simple configuration, and minimal user training time [19]. Erwei Yin et al. introduced an optimized SSVEP speller with enhanced performance regarding classification accuracy and spelling speed [20]. However, errors in detection can significantly impact performance. It has been proposed that accuracy can be improved by measuring error-related potentials (ErrP), which are detectable when a user perceives or makes an error [5]. Experiments by Spu¨ler et al. show that ErrP can facilitate error correction in synchronous BCIs [21].

Motor Imagery BCI (MIBCI) systems use imagined movements to generate EEG signals. Despite progress, the communication accuracy (CA) of MIBCI systems remains significantly lower than desired levels of communication effectiveness [12,13]. This limitation highlights the ongoing challenges in making MIBCI systems practical for real-world use [22].

Despite decades of research, spelling via BCI remains a challenging task for individuals with severe disabilities. This paper provides a summary of BCI’s development while acknowledging limitations in addressing non-systematic performance factors such as environmental or psychological influences [10,12,17].

4. Conclusion

Overall, this thesis reviews the methods for detecting event-related potentials (ERPs). Proposing the rehabilitation of the eye using current technology, for example, steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP) and frequency visual evoked potential (f-VEP) for treating ocular motility disorder and developing eye prosthetics [6,18]. With this aim, the P300 speller has the potential to be used in the eye, which can analyze P300 electrical signals and ERPs (event-related potentials) generated using the oddball paradigm, which is significant for developing a brain-computer interface (BCI) [23]. The improvement in P300 is mainly reflected in the transmission of neural networks performed in signal processing and detection technology, such as motor imagery [12,13]. However, the graphical user interface has not progressed in the last two decades [10]. The P300 can help spell characters for people who have lost the ability to speak and write and has great potential to be an effective communication device [23]. Steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEP), due to their high information rate (ITR), have become a mainstream technical route at present [15,19]. Although Erwei Yin et al. proposed an SSVEP speller that is faster and more accurate than the previous SSVEP, error detection with this method will greatly affect performance [23]. Therefore, I proposed measuring the potential related to error (ErrP) to improve detection accuracy, and ErrP was also confirmed by Spuler et al. that it can be used for error correction [20]. Thomsend et al. proposed another alternative paradigm different from RCP, called the checkerboard paradigm (CBP), which can greatly alleviate confusion around the target [7]. In one test, CBP achieved 92 percent accuracy compared to 77 percent for RCP, while also improving the rate of information delivery. Although the current P300 speller has many advantages, it cannot be used in the commercial field because of various problems such as robustness and user interface adaptability [10].

Some areas of research are constantly improving, such as the P300 and SSVEP spellers, while others are using entirely new technologies such as ErrP [20]. In the future, the EEG field will likely merge these different paths to integrate the best of both worlds, both the optimization of past techniques and cutting-edge approaches [22,24-27]. With the rapid development of the fields of neuroscience, biomedical engineering, and artificial intelligence, BCI technology has begun to move from the laboratory to clinical trials and commercialization, especially the application of noninvasive BCI devices in the field of medical rehabilitation [21,22,28,29]. Although the BCI industry has made significant progress, there are still several challenges such as technical issues, privacy protection, cost control, and so on [6,19]. The technical problems mainly focus on the collected signal’s accuracy and the equipment’s compatibility [18,20]. With the continuous progress of technology, the market demand is growing. As far as the whole non-invasive BCI field is concerned, the current mainstream technical route is still in the development stage [19,10]. This study provides some insights into this ongoing area of research, demonstrating the advantages of existing identification techniques while also pointing out the limitations of various approaches [23,30].

References

[1]. J. J. Shih, D. J. Krusienski, and J. R. Wolpaw, “Brain-Computer Interfaces in Medicine, ” PMC, [Online]. Available: https: //www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3497935/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[2]. S. Gali, V. Midhula, A. Naimpally, H. B. Lanka, K. Melepurra, and C. Bhandary, “Troubleshooting Ocular Prosthesis: A Case Series, ” PMC, [Online]. Available: https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC9416110/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[3]. S. Cheng, J. Wang, L. Zhang, and Q. Zhang, “Motion Imagery-BCI Based on EEG and Eye Movement Data Fusion, ” IEEE Xplore, [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9311662. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[4]. M. Middendorf, “Brain-computer interfaces based on the steady-state visual-evoked response, ” IEEE Xplore, 2000. [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/847819. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[5]. M. S. Ali, A. Hassan, A. Rahim, M. H. Ashraf, A. Rahim, and S. Saghir, “Motor imagery EEG classification using fine-tuned deep convolutional efficientnetb0 model, ” in 2023 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ICAI), pp. 1-6, 2023.

[6]. X. Zhang, “Age-related differences in the transient and steady state responses to different visual stimuli, ” PubMed, 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36158550/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[7]. G. Townsend, “A novel P300-based brain-computer interface stimulus presentation paradigm: moving beyond rows and columns, ” PubMed, 2010. [Online]. Available: https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20347387/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[8]. K. Karas, L. Pozzi, A. Pedrocchi, et al., “Brain-computer interface for robot control with eye artifacts for assistive applications, ” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 17512, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44645-y.

[9]. L. Mayaud, “Robust brain-computer interface for virtual keyboard (RoBIK): Project results, ” Science Direct, 2013. [Online]. Available: https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/ S1959031813000262. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[10]. I. Volosyak, “Evaluation of the Bremen SSVEP based BCI in real world conditions, ” IEEE Xplore, 2009. [Online]. Available: https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/224580443 Evaluation of the Bremen SSVEP based BCI in real world conditions. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[11]. B. Blankertz, “The Berlin brain-computer interface presents the novel mental typewriter Hex-O-Spell, ” ResearchGate, 2006. [Online]. Available: https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/45488894 The Berlin brain-computer interface presents the novel mental typewriter Hex-O-Spell. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[12]. C. M. Yilmaz, “Classification of EEG-based motor imagery tasks using 2-D features and quasi-probabilistic distribution models, ” Ph.D. dissertation, 2021.

[13]. M. Wei, R. Yang, and M. Huang, “Motor imagery EEG signal classification based on deep transfer learning, ” in 2021 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), pp. 85-90, 2021.

[14]. D. Farina, I. Vujaklija, R. Bra˚nemark, et al., “Toward higher performance bionic limbs for wider clinical use, ” Nat. Biomed. Eng, vol. 7, pp. 473–485, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00732-x.

[15]. R. Abiri, S. Borhani, E. W. Sellers, Y. Jiang, and X. Zhao, “A comprehensive review of EEG-based brain-computer interface paradigms, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 011001, Feb. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aaf12e.

[16]. Z. Wang, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, B. Gu, S. Liu, M. Xu, H. Qi, F. He, and D. Ming, “A BCI-based visual-haptic neurofeedback training improves cortical activations and classification performance during motor imagery, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 066012, Oct. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab377d.

[17]. S. Chaudhary, S. Taran, V. Bajaj, and A. Sengur, “Convolutional neural network based approach towards motor imagery tasks EEG signals classification, ” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 4494-4500, Jun. 2019.

[18]. Z. Wang, N. Shi, Y. Zhang, et al., “Conformal in-ear bioelectronics for visual and auditory brain-computer interfaces, ” Nat Commun, vol. 14, no. 4213, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39814-6.

[19]. E. Yin, Z. Zhou, J. Jiang, Y. Yu and D. Hu, “A Dynamically Optimized SSVEP Brain–Computer Interface (BCI) Speller, ” in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 1447-1456, June 2015, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2320948.

[20]. Spu¨ler, Martin, Laßmann, Christian. (2015). Error-related potentials during continuous feedback: using EEG to detect errors of different type and severity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00155.

[21]. T. Fang, “Recent advances of P300 speller paradigms and algorithms, ” IEEE Explore, 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/ abstract/document/9385369. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[22]. H. Song, T. H. Hsieh, S. H. Yeon, et al., “Continuous neural control of a bionic limb restores biomimetic gait after amputation, ” Nat Med, vol. 30, pp. 2010–2019, 2024. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02994-9.

[23]. Y. Okahara, K. Takano, M. Nagao, et al., “Long-term use of a neural prosthesis in progressive paralysis, ” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 16787, 2018. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35211-y.

[24]. Z. Wang, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, B. Gu, S. Liu, M. Xu, H. Qi, F. He, and D. Ming, “A BCI-based visual-haptic neurofeedback training improves cortical activations and classification performance during motor imagery, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 066012, Oct. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab377d.

[25]. M. Yang, T. P. Jung, J. Han, M. Xu, and D. Ming, “A review of researches on decoding algorithms of steady-state visual evoked potentials, ” Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 416-425, Apr. 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.7507/1001-5515.202111066.

[26]. I. Vigue´-Guix, L. Mor´ıs Ferna´ndez, M. Torralba Cuello, M. Ruzzoli, and S. Soto-Faraco, “Can the occipital alpha-phase speed up visual detection through a real-time EEG-based brain-computer interface (BCI)?”, Eur J Neurosci., vol. 55, no. 11-12, pp. 3224-3240, Jun. 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14931.

[27]. A. Ravi, J. Lu, S. Pearce, and N. Jiang, “Enhanced system robustness of asynchronous BCI in augmented reality using steady-state motion visual evoked potential, ” IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng., vol. 30, pp. 85-95, 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2022.3140772.

[28]. “Motor-Imagery EEG-Based BCIs in Wheelchair Movement and Control: A Systematic Literature Review, ” MDPI, 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.3390/s21186285. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[29]. G. Wang, G. Marcucci, B. Peters, et al., “Human-centred physical neuromorphics with visual brain-computer interfaces, ” Nat Commun, vol. 15, no. 6393, 2024. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50775-2.

[30]. M. Nakanishi, “Generating visual flickers for eliciting robust steady-state visual evoked potentials at flexible frequencies using monitor refresh rate, ” PLOS ONE, 2014. [Online]. Available: https: //journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0099235. [Accessed: 21-Sep2024].

Cite this article

Wang,A. (2025). Visual Brain-Machine Interface — Reproduction of Sight Using Current Technology: A Literature Review. Applied and Computational Engineering,199,8-19.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of CONF-SEML 2025 Symposium: Machine Learning Theory and Applications

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. J. J. Shih, D. J. Krusienski, and J. R. Wolpaw, “Brain-Computer Interfaces in Medicine, ” PMC, [Online]. Available: https: //www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3497935/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[2]. S. Gali, V. Midhula, A. Naimpally, H. B. Lanka, K. Melepurra, and C. Bhandary, “Troubleshooting Ocular Prosthesis: A Case Series, ” PMC, [Online]. Available: https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC9416110/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[3]. S. Cheng, J. Wang, L. Zhang, and Q. Zhang, “Motion Imagery-BCI Based on EEG and Eye Movement Data Fusion, ” IEEE Xplore, [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9311662. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[4]. M. Middendorf, “Brain-computer interfaces based on the steady-state visual-evoked response, ” IEEE Xplore, 2000. [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/847819. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[5]. M. S. Ali, A. Hassan, A. Rahim, M. H. Ashraf, A. Rahim, and S. Saghir, “Motor imagery EEG classification using fine-tuned deep convolutional efficientnetb0 model, ” in 2023 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ICAI), pp. 1-6, 2023.

[6]. X. Zhang, “Age-related differences in the transient and steady state responses to different visual stimuli, ” PubMed, 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36158550/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[7]. G. Townsend, “A novel P300-based brain-computer interface stimulus presentation paradigm: moving beyond rows and columns, ” PubMed, 2010. [Online]. Available: https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20347387/. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[8]. K. Karas, L. Pozzi, A. Pedrocchi, et al., “Brain-computer interface for robot control with eye artifacts for assistive applications, ” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 17512, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44645-y.

[9]. L. Mayaud, “Robust brain-computer interface for virtual keyboard (RoBIK): Project results, ” Science Direct, 2013. [Online]. Available: https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/ S1959031813000262. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[10]. I. Volosyak, “Evaluation of the Bremen SSVEP based BCI in real world conditions, ” IEEE Xplore, 2009. [Online]. Available: https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/224580443 Evaluation of the Bremen SSVEP based BCI in real world conditions. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[11]. B. Blankertz, “The Berlin brain-computer interface presents the novel mental typewriter Hex-O-Spell, ” ResearchGate, 2006. [Online]. Available: https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/45488894 The Berlin brain-computer interface presents the novel mental typewriter Hex-O-Spell. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[12]. C. M. Yilmaz, “Classification of EEG-based motor imagery tasks using 2-D features and quasi-probabilistic distribution models, ” Ph.D. dissertation, 2021.

[13]. M. Wei, R. Yang, and M. Huang, “Motor imagery EEG signal classification based on deep transfer learning, ” in 2021 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), pp. 85-90, 2021.

[14]. D. Farina, I. Vujaklija, R. Bra˚nemark, et al., “Toward higher performance bionic limbs for wider clinical use, ” Nat. Biomed. Eng, vol. 7, pp. 473–485, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00732-x.

[15]. R. Abiri, S. Borhani, E. W. Sellers, Y. Jiang, and X. Zhao, “A comprehensive review of EEG-based brain-computer interface paradigms, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 011001, Feb. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aaf12e.

[16]. Z. Wang, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, B. Gu, S. Liu, M. Xu, H. Qi, F. He, and D. Ming, “A BCI-based visual-haptic neurofeedback training improves cortical activations and classification performance during motor imagery, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 066012, Oct. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab377d.

[17]. S. Chaudhary, S. Taran, V. Bajaj, and A. Sengur, “Convolutional neural network based approach towards motor imagery tasks EEG signals classification, ” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 4494-4500, Jun. 2019.

[18]. Z. Wang, N. Shi, Y. Zhang, et al., “Conformal in-ear bioelectronics for visual and auditory brain-computer interfaces, ” Nat Commun, vol. 14, no. 4213, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39814-6.

[19]. E. Yin, Z. Zhou, J. Jiang, Y. Yu and D. Hu, “A Dynamically Optimized SSVEP Brain–Computer Interface (BCI) Speller, ” in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 1447-1456, June 2015, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2320948.

[20]. Spu¨ler, Martin, Laßmann, Christian. (2015). Error-related potentials during continuous feedback: using EEG to detect errors of different type and severity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00155.

[21]. T. Fang, “Recent advances of P300 speller paradigms and algorithms, ” IEEE Explore, 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //ieeexplore.ieee.org/ abstract/document/9385369. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[22]. H. Song, T. H. Hsieh, S. H. Yeon, et al., “Continuous neural control of a bionic limb restores biomimetic gait after amputation, ” Nat Med, vol. 30, pp. 2010–2019, 2024. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02994-9.

[23]. Y. Okahara, K. Takano, M. Nagao, et al., “Long-term use of a neural prosthesis in progressive paralysis, ” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 16787, 2018. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35211-y.

[24]. Z. Wang, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, B. Gu, S. Liu, M. Xu, H. Qi, F. He, and D. Ming, “A BCI-based visual-haptic neurofeedback training improves cortical activations and classification performance during motor imagery, ” J Neural Eng., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 066012, Oct. 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab377d.

[25]. M. Yang, T. P. Jung, J. Han, M. Xu, and D. Ming, “A review of researches on decoding algorithms of steady-state visual evoked potentials, ” Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 416-425, Apr. 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.7507/1001-5515.202111066.

[26]. I. Vigue´-Guix, L. Mor´ıs Ferna´ndez, M. Torralba Cuello, M. Ruzzoli, and S. Soto-Faraco, “Can the occipital alpha-phase speed up visual detection through a real-time EEG-based brain-computer interface (BCI)?”, Eur J Neurosci., vol. 55, no. 11-12, pp. 3224-3240, Jun. 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14931.

[27]. A. Ravi, J. Lu, S. Pearce, and N. Jiang, “Enhanced system robustness of asynchronous BCI in augmented reality using steady-state motion visual evoked potential, ” IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng., vol. 30, pp. 85-95, 2022. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2022.3140772.

[28]. “Motor-Imagery EEG-Based BCIs in Wheelchair Movement and Control: A Systematic Literature Review, ” MDPI, 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.3390/s21186285. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2024].

[29]. G. Wang, G. Marcucci, B. Peters, et al., “Human-centred physical neuromorphics with visual brain-computer interfaces, ” Nat Commun, vol. 15, no. 6393, 2024. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50775-2.

[30]. M. Nakanishi, “Generating visual flickers for eliciting robust steady-state visual evoked potentials at flexible frequencies using monitor refresh rate, ” PLOS ONE, 2014. [Online]. Available: https: //journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0099235. [Accessed: 21-Sep2024].