1. Introduction

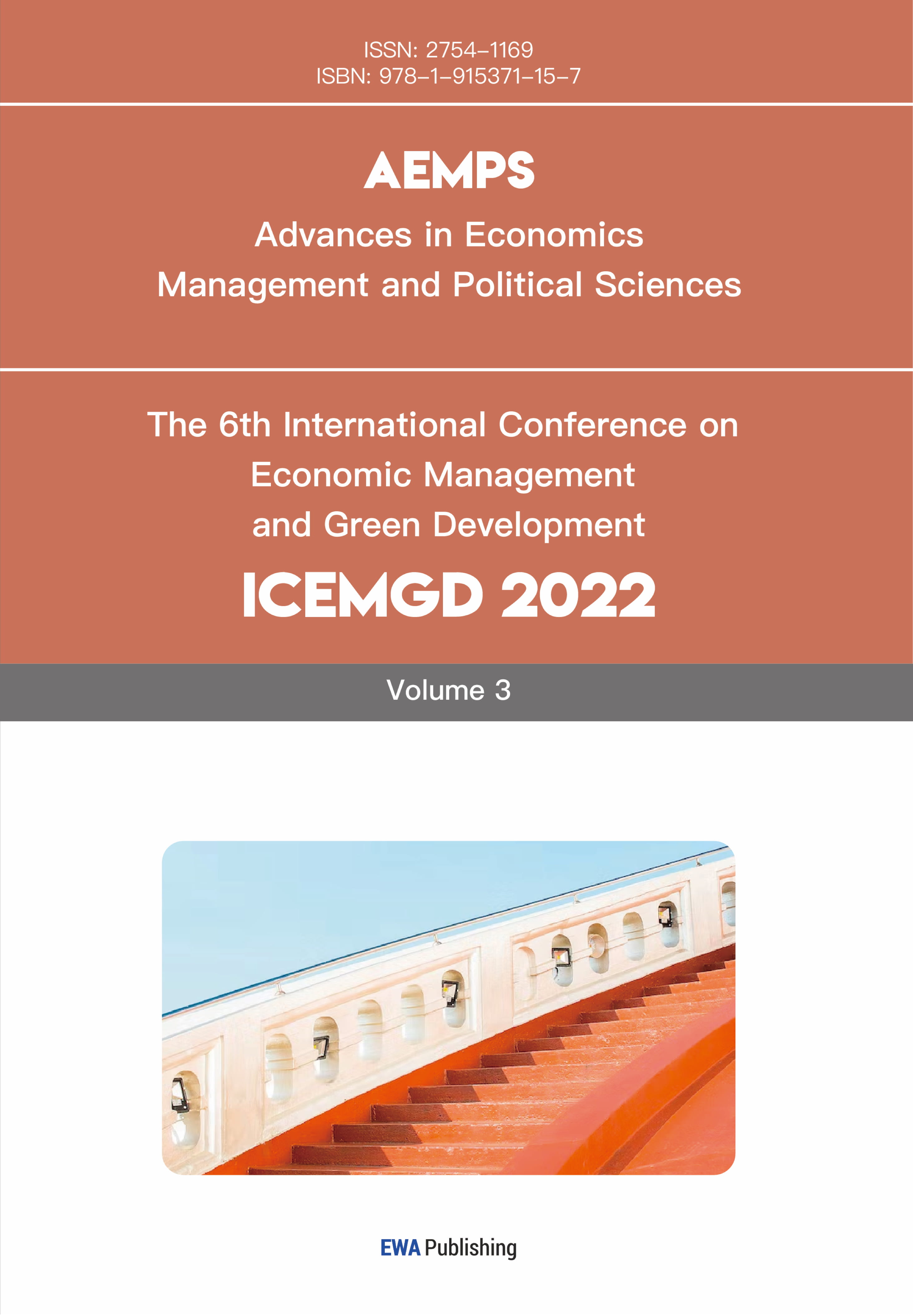

As an important goal to measure the economic development and social stability of a country and a region, the importance of the employment rate is self-evident. However, according to statistics released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China, the youth unemployment rate in the Chinese labor market has witnessed a sharp increase from 2018-2023, reaching a record high of 21.3% in June 2023(See Fig.1). As shown in Figure 1, China’s youth unemployment rate reached a record low of 9.6% in May 2018 and then kept climbing up in the following five years. The youth unemployment rate refers to the share of the total workforce aged 16 to 24 who are currently unemployed except students actively searching for jobs. Even with new calculation methods from NBS, the youth unemployment rate is still 17.1% in July 2024 [1]. Although the unemployment rate in 2024 has dropped, it remains elevated compared to the historical average, indicating a serious social issue that continues to exert great pressure on the job market [2]. This paper finds that the consistent youth unemployment rate in China in the past decade is the result of the undergoing structural transition, the implementation of an eight-hour day, the mismatch between education disciplines and market needs, the cultural beliefs for white-collar jobs, together with the social phenomenon known as “Lying Flat” or “Rat Race.”

Source: www.ceicdata.com

2. The illusion of the eight-hour day: labor policy loopholes and their impact on employment opportunities

The unsatisfactory implementation of an eight-hour day will allocate more workload to one individual, releasing fewer job opportunities, leading to higher unemployment rate. It is known that China claimed that it obeyed the eight-hour day and put it into law, however, the actual implementation of the eight-hour day in China is not optimistic. According to the data from Statista. In July 2024, employees surveyed by enterprises in China worked an average of 48.7 hours per week, slightly higher than the 48.6 hours per week recorded on average in 2023 [2]. Moreover, some companies exploit legal loopholes to force overtime work. Hu showed the data in The China Project, “loopholes in existing labor laws allow companies to require employees to work overtime without pay by arguing they 'voluntarily’ chose to forgo extra wages. Most Huawei employees, for example, sign a 'voluntary’ agreement to give up paid annual leave and to work hard for the company.” It illustrates the implementation of an eight-hour day in China is not ideal. The American Journal of Sociology shows the effect of working shorter time one day [3]. It demonstrates that overproduction, unemployment, and poverty are the root causes of economic issues. Greater pay and fewer hours worked can be used to lessen this load. As a result, there is a rise in demand for goods, wider consumption, and higher living standards. Therefore, the implementation of an eight-hour day is important in decreasing the unemployment rate. It can be seen that the high unemployment rate in China is related to the unsatisfactory implementation of the eight-hour day.

The effect of an eight-hour day to unemployment rate in China is different in state-owned enterprises and private enterprises. The relationship between the eight-hour working day from the perspective of labor market supply and demand has been analyzed above. However, the enterprises that do not fully follow the supply and demand of the labor market should also be emphasized, such as China's state-owned enterprises. Although there is a difference in working time between SOEs and private enterprises, according to Qi, “the working week was 46.16 hours in SOEs, compared to 53.16 hours in private enterprises” [4]. Social incidents like private business owners advocating longer working hours to exploit employees are also common, for example, Li investigated that many CEOs of sizable Internet-related businesses are in favor of the 996 working hour schedule [5]. The 996 working hour system is a "repaired blessing," according to Jack Ma, who stated as much at Alibaba's internal meeting." These are morally righteous employee abductions occurring during regular business hours. However, the shorter working time of SOEs can be an attractive factor to people but not the reason of low unemployment rate, because the employment and dismissal of SOEs do not fully comply with the supply and demand relationship in the labor market, which does not conform to the logical chain of how the eight-hour workday affects the unemployment rate that has been mentioned before.

The unemployment situation of state-owned enterprises is more affected by national policies rather than the market. This is because China's state-run enterprises operate not totally for profit but also consider the public good (such as decreasing the unemployment rate). According to Feng, Hu, and Robert, between 1988 and 1995, the unemployment rate was a mere 3.7% on average [5]. The urban labor market was still dominated by the so-called "iron rice bowl," which consisted primarily of lifetime employment in the state sector and state-assigned jobs. However, because of the policy of “seizing the large and letting go of the small, which leads to an estimated 34 million state sector employees were laid off between 1995 and 2001 [6]. It shows the effect of policy on SOEs, when SOEs had a dominant position under the planned economy in the last century, the unemployment rate was low and stable because jobs were allocated by the government, and SOEs rarely fired employees under normal circumstances. Similarly, when the Chinese government implements the reform and opening up strategy for the overall interests of the country, there are thousands of people fired by SOEs.

Moreover, the research done by Tomoo also showed it, from the graph including regions with the highest unemployment in 2000 and 2010, it is obvious that the regions with the highest unemployment rate is almost located in the heavy industry bases in the northeast, which are all SOEs controlled by nation strictly. The unemployment rate of most of them is higher than 20%, which is incredibly much higher than the normal unemployment rate of SOEs mentioned before [7]. The high unemployment rate coincides with the same period of state-owned enterprises' substantial layoffs because of reform and opening up. Similarly, state-owned enterprises will also recruit employees regardless of corporate profits to achieve Macro-control targets. From Wen, private companies lay off workers when the market for Chinese exports is negatively impacted, but SOEs inexplicably hire more people. Ultimately, following flood catastrophes, SOEs hire more workers while private companies once again reduce staffing [8]. In summary, SOE employment appears to counteract the demographic and economic forces that contribute to unrest. Moreover, for the stability of the country, state-owned enterprises rarely fire employees under normal circumstances regardless of redundant employee issues. Yin investigates that in central planning economies such as China, overstaffing was a common occurrence, as planning authorities prioritized output targets over efficiency or profits [8]. Unlike traditional private businesses, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are subject to limitations from the government. One of these restrictions is that if the employees refuse to be fired, they cannot just fire unnecessary employees to boost profits.

As a result, the unemployment rate in SOEs is not linked to the eight-hour day, because they rarely fire employees, which is also the reason behind the low unemployment rate around the country when SOEs dominated [9]. The SOEs don’t regard profits as the first goal, it is more like a national macro-control tool, so they is affected by the market smaller than private enterprises, however, eight hours working day affects the unemployment rate through supply and demand relationship in the market, so China's state-owned enterprise unemployment is affected by eight hours workday smaller than the private enterprise.

Besides considering the fewer employment opportunities caused by the unsatisfactory implementation of an eight-hour day, the efficiency issue should be included. The unsatisfactory implementation of the eight-hour day will also influence people’s working enthusiasm and satisfaction, decreasing efficiency, making the same workload done by more people, releasing more jobs, and decreasing the unemployment rate in turn. Zheng finds that extended working hours are associated with increased fatigue and less productivity [9]. So, it is reasonable to doubt that the unsatisfactory implementation of an eight-hour day in China will release more jobs by decreasing individual efficiency and productivity. However, it is hard to quantify the negative and positive effects of the unsatisfactory implementation of eight-hour days to unemployment rate and how they cancelled out with each other. But one thing we can ensure is that the unsatisfactory implementation of an eight-hour day has a negative effect on the overall development of one country whether in the aspect of decreasing efficiency or increasing the unemployment rate.

3. In the throes of development: economic transition and skill mismatches fueling youth unemployment in China

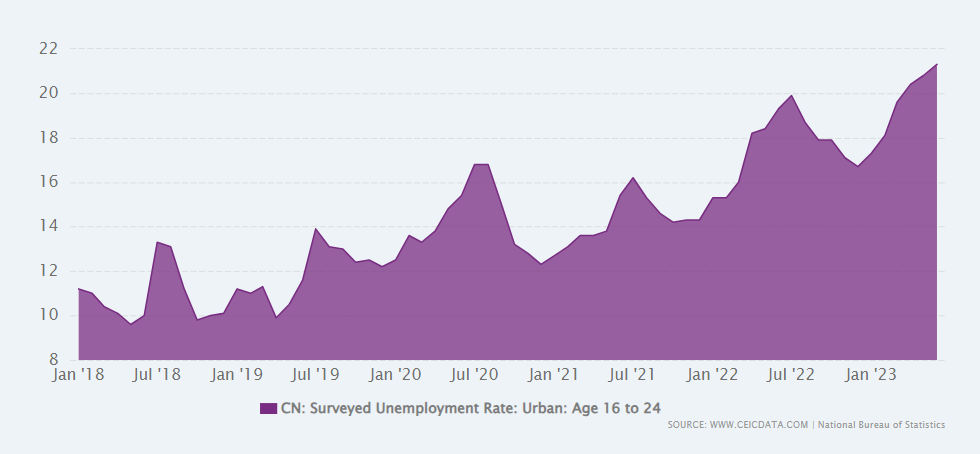

Over the past decade, China’s economy has undergone a structural transition from high-speed growth driven by manufacturing and exports to a more balanced model focusing on high technology and domestic consumption, which has led to major changes in labor demands. As shown in Figure 2, China’s Real Annual GDP growth averaged 9.5 from 2007 to 2013 and started to slow down in 2014 until 2024 [10]. The slow-down economic trend in China in the past decade is the result of China’s structural transition as China is transitioning from high-speed growth in GDP to a more balanced economic model, aiming to improve the quality and sustainability of the overall economic development. Under such context, the slowing growth and the structural adjustment to high technology have led to reduced demand in traditional industries such as labor-intensive manufacturing, affecting job creation for young workers. In the meantime, technological innovation together with the rise of AI has led to a national shortage of talent in high-tech sectors, such as digital talents, system architects, software professionals, natural language processing engineers, and AI experts. According to news from China Daily, China now faces a digital talent shortage of about 25 million to 30 million workers, especially in e-commerce, software engineering, as well as emerging fields, such as AI, biomedical engineering, and new energy sectors. Those changes in labor demands are directly tied to China’s ongoing economic transition [11].

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Another critical factor contributing to the high youth unemployment in the Chinese labor market is the growing mismatch between the education young people acquire in universities and the actual demand of the labor market. According to statistics released at Statista, the number of college graduates has been increasing steadily in the past decade, reaching nearly 11.5 million in 2023 and nearly 12 million in 2024 [12]. However, the increasing number of college graduates has not improved the staggering unemployment rate in China. In a study published in 2023, Beishan Xiang, Huiying Wang, and Huimin Wang analyzed the paradox in China’s job market, especially the educational mismatch issue in China [13]. According to their study, the rapid expansion of higher education in China has led to an oversupply of graduates, however, the stagnant employment rate of college graduates demonstrates a paradox, which is the result of the inconsistency in academic disciplines, together with the mismatch between core competences of students with the demand of the market. It means that the knowledge and skills that students have learned in colleges and universities are not exactly what the market is asking for. As to the underlying causes of such mismatch, their analysis reveals a disappointing fact that “China’s labor market is unable to accommodate such a large number of college graduates,” primarily due to the imbalances between the economic development level and scale of higher education in many areas, and also the mismatch between academic disciplines with the actual need of the market [14]. Specifically, Xiang, Wang, and Wang explain the problems with China’s current academic disciplines, especially the limited autonomy of universities in making decisions in specific subjects and professions as well as slow adjustments based on market demands. For example, the employment rates for students in disciplines such as law, science, art, and literature are lower compared with others such as engineering, medicine, and other high-tech-related disciplines, but the number of graduates in those fields remains high. As a result, many graduates who majored in those less needed disciplines such as law and art find themselves lacking the practical skills needed to find employment in emerging industries or secure jobs that match their qualifications and expectations.

4. Bridging the divide: regional disparities in vocational education and their role in youth employment challenges

Additionally, the regional imbalances in the development level and the availability of vocational education further complicate the issue. Vocational education institutions are primarily located in provincial capitals and more economically developed regions. The economic development level is very uneven in China when the Eastern regions and provincial capitals are much more economically developed than other regions, which gave rise to the development of vocational educational institutions in those areas. However, for less developed regions, vocational training institutions are not available to young people, depriving them of their opportunities to gain new skills required in the job market. Therefore, the imbalanced regional distribution of vocational education poses another challenge for young people living in other areas to have access to vocational training to acquire the skills needed to enter the workforce, especially for new industries and technologies. In contrast, Germany’s Dual Vocational Training System offers a better education system that matches the needs of the job market. Professor Dr. Dieter Euler explores the success of Germany’s Dual Vocational Training by explaining its advantages in the combination of academic learning with labor market needs, clear career development path for students, high level of corporate involvement in curriculum development, and low level of unemployment rate [15]. Although Germany has quite different social, economic, and institutional frameworks from China, the success of Germany’s Dual Vocational Training Systems and its low unemployment serves as a great example to show the significant role of educational systems in driving the mismatch in the labor market.

5. The ambition paradox: how higher education expansion and the 'Lying Flat' movement shape youth unemployment in China

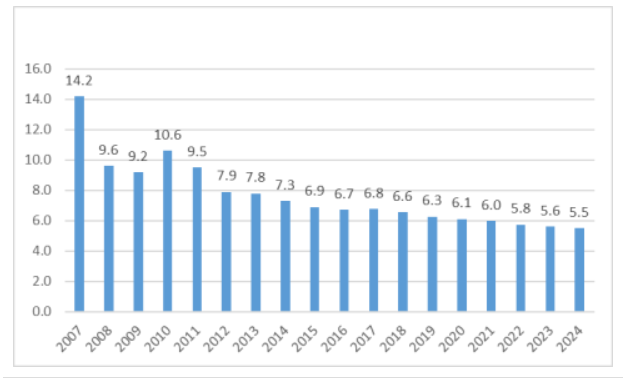

Furthermore, the expansion of higher education in China has also shaped graduates’ beliefs and choices, leading to higher expectations and preferences for high-paying white-collar jobs. According to the study of Zedong Han and Yun Wang, higher education expansion, especially as educational investments, has led to changes in graduates’ beliefs, expectations, and choices [16]. Specifically, graduates expect to find white-collar jobs that pay well because it is the only way to make up to their efforts and investment made in higher education. Such expectations and beliefs will lead to unsatisfactory labor market outcomes as many graduates are reluctant to take under-paying jobs or blue-collar jobs. Some of them might decide to pursue postgraduate education to avid the job search challenges. Yangqiao Zheng, Xiaoqi Zhang, and Yu Zhu conducted a study on the mismatch in higher education based on data from an online recruitment platform in China. In their study, they pointed out the “overeducation” issue in China's higher education as half of online job-seekers in China are two or more years overeducated, which will also lead to pay penalties to varying degrees based on education quality [17]. This study highlights how degree inflation will negatively affect the economic return of some college majors, and even lead to pay penalties. However, the actual market demand in the labor market shows an increase in service and blue-collar jobs such as technicians, food delivery workers, truck drivers, etc., which contrasts with the growing number of overeducated individuals seeking white-collar positions. According to China's biggest recruitment website, Zhaopin’s latest report, market demands for blue-collar jobs such as delivery workers have witnessed steady growth since 2019 until the first quarter of 2024. As shown in Figure 3, taking the number of the market need for blue-collar workers in the first quarter of 2019 as the baseline, the number has increased by 3.79 times in the first quarter of 2024 [18]. The service sectors in China are expanding rapidly, offering more flexible employment opportunities to young people. However, the low social recognition for blue-collar jobs, especially among college graduates remains a major challenge for them to consider those jobs. Therefore, the mismatch between young people’s expectations for white-collar jobs with the actual market demand for blue-collar jobs is another reason that can be used to explain the increasing unemployment rate in China.

In addition, the social trend of the “Lying Flat” phenomenon in China also contributes to the rising unemployment rate as many young people are responding to the pressure of modern life and challenges in the job market by opting out. Changheng Zhou explains the term “Lying Flat” as “living a life without ambition” and how it fits in the context of the worldwide economic downturn, especially the mentality of Chinese young people [19].

By adopting a “lying flat” attitude, many young people reject the traditional pursuit of career success and choose a minimalist lifestyle. Some of them returned to their hometowns, took freelance or part-time jobs, or stay with their parents instead of working. China’s notorious “996 work culture,” meaning working from 9 am to 9 pm for 6 days a week, was very common in many startups, private, and high-tech companies, which has been a huge push factor for many young employers to quit or give up looking for jobs [20]. The “Lying Flat” phenomenon is their passive strategy to confront the competitive nature and pressure of the job market and the high cost of living in urban areas [21]. However, as many young people are “Lying Flat” for various economic, social, or personal reasons, it will pose a great challenge to the labor market, resulting in increased unemployment.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the high unemployment rate in China is a complex issue driven by multiple factors, including China’s economic transition, the mismatch between education and labor market demands, cultural preferences for white-collar jobs among Chinese young people, and the growing social trend of “Lying Flat.” Investigating the underlying causes for the persistent unemployment rate in China from multiple perspectives is critical to fully understanding the issue and then make meaningful actions to address all those challenges faced by Chinese young people in the labor market.

References

[1]. Si Cheng, “Cultivation of digital talent urged Government aims to address the shortage of workers as nation's 'smarter' economy begins taking shape, ” China Daily. June, 6. 2024, https: //www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202406/26/WS667b5bd9a31095c51c50ad78.html

[2]. “China Unemployment Rate: Age 16 to 24, ” CEIC. n.d. https: //www.ceicdata.com/en/china/surveyed-unemployment/cn-unemployment-rate-age-16-to-24

[3]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Youth Unemployment Soars above 17% in July, Highest since New System Began in December, ” CNBC. Aug, 20. 2024, https: //www.cnbc.com/2024/08/20/chinas-youth-unemployment-soars-above-17percent-in-july.html

[4]. Statista. “Average Weekly Working Hours in China July 2022-2024.” Statista, 15 Aug. 2024, www.statista.com/statistics/1391557/weekly-average-working-hours-china.

[5]. Hu, Lelan. “Eight-hour Workday? In China, Overworked Employees Are Lobbying for It.” The China Project, 11 May 2021, thechinaproject.com/2021/02/10/eight-hour-workday-in-china-workers-lobby.

[6]. Qi, Hao, and David M. Kotz. “The Impact of State-Owned Enterprises on China’s Economic Growth.” Review of Radical Political Economics, vol. 52, no. 1, June 2019, pp. 96–114. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0486613419857249

[7]. Li, Dandan, et al. “A Controversial Working System in China: The 996 Working Hour System.” 2021 International Conference on Arts, Law and Social Sciences (ALSS 2021), 2021.

[8]. Feng, Shuaizhang, et al. Long Run Trends in Unemployment and Labor Force Participation in China / Shuaizhang Feng, Yingyao Hu, Robert Moffitt. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015.

[9]. Marukawa, Tomoo. “Regional Unemployment Disparities in China.” Economic Systems, vol. 41, no. 2, June 2017, pp. 203–14. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2016.11.002.

[10]. “Subsidising Stability: State Employment in China.” VoxDev, voxdev.org/topic/institutions-political-economy/subsidising-stability-state-employment-china.

[11]. Zheng, Hongyun, et al. “Working Hours and Job Satisfaction in China: A Threshold Analysis.” China Economic Review, vol. 77, Feb. 2023, p. 101902. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101902.

[12]. Francisc Betti, “How China’s shifting industries are reshaping its long-term growth model, ” World Economic Forum, June 28, 2024, https: //www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/06/how-china-s-shifting-industries-are-reshaping-its-long-term-growth-model/

[13]. C. Textor, “Number of college and university graduates in China 2013-2023, ” Statista, May 31, 2024, https: //www.statista.com/statistics/227272/number-of-university-graduates-in-china/#: ~: text=In%202023%2C%20a%20record%20high, education%20in%20the%20United%20States

[14]. Beishan Xiang, Huiying Wang, and Huimin Wang. “Is There a Surplus of College Graduates in China? Exploring Strategies for Sustainable Employment of College Graduates, ” Sustainability, 15, (2023): 15540. p. 2.

[15]. Yong Han, et al. “Supply and demand of higher vocational education in China: Comprehensive evaluation and geographical representation from the perspective of educational equality, ” PLOS ONE, 18, no.10. (2023): e0293132.

[16]. Zedong Han and Yun Wang, “Education signaling, effort investments, and the market's expectations: Theory and experiment on China's higher education expansion, ” China Economic Review, vol. 75, (Oct. 2022), https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101848

[17]. Yangqiao Zheng, Xiaoqi Zhang, and Yu Zhu, “Overeducation, major mismatch, and return to higher education tiers: Evidence from novel data source of a major online recruitment platform in China, ” China Economic Review, 66. (April 2021). https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101584

[18]. Dongli Liu, “2024 Blue-Collar Worker Development Report by Zhaopin, ” Sohu. June 7 2024, https: //www.sohu.com/a/784325961_121284943

[19]. Changheng Zhou, “Lying Flat’ and Rejecting the Rat Race: The Survival Anxiety of Chinese Youth, ” Science Insights, 41, no.7, (2022), p.741.

[20]. McVey, Frank L. “The Social Effects of the Eight-Hour Day.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 8, no. 4, Jan. 1903, pp. 521–30. https: //doi.org/10.1086/211157.

[21]. Remington, Thomas F., and Xiao Wen Cui. “The Impact of the 2008 Labor Contract Law on Labor Disputes in China.” Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, Aug. 2015, pp. 271–99. https: //doi.org/10.1017/s1598240800009371.

Cite this article

He,S.;Zhu,Y. (2025). The Analysis of Factors Contributing to the High Youth Unemployment Rate in the Chinese Labor Market. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,217,165-172.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Si Cheng, “Cultivation of digital talent urged Government aims to address the shortage of workers as nation's 'smarter' economy begins taking shape, ” China Daily. June, 6. 2024, https: //www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202406/26/WS667b5bd9a31095c51c50ad78.html

[2]. “China Unemployment Rate: Age 16 to 24, ” CEIC. n.d. https: //www.ceicdata.com/en/china/surveyed-unemployment/cn-unemployment-rate-age-16-to-24

[3]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Youth Unemployment Soars above 17% in July, Highest since New System Began in December, ” CNBC. Aug, 20. 2024, https: //www.cnbc.com/2024/08/20/chinas-youth-unemployment-soars-above-17percent-in-july.html

[4]. Statista. “Average Weekly Working Hours in China July 2022-2024.” Statista, 15 Aug. 2024, www.statista.com/statistics/1391557/weekly-average-working-hours-china.

[5]. Hu, Lelan. “Eight-hour Workday? In China, Overworked Employees Are Lobbying for It.” The China Project, 11 May 2021, thechinaproject.com/2021/02/10/eight-hour-workday-in-china-workers-lobby.

[6]. Qi, Hao, and David M. Kotz. “The Impact of State-Owned Enterprises on China’s Economic Growth.” Review of Radical Political Economics, vol. 52, no. 1, June 2019, pp. 96–114. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0486613419857249

[7]. Li, Dandan, et al. “A Controversial Working System in China: The 996 Working Hour System.” 2021 International Conference on Arts, Law and Social Sciences (ALSS 2021), 2021.

[8]. Feng, Shuaizhang, et al. Long Run Trends in Unemployment and Labor Force Participation in China / Shuaizhang Feng, Yingyao Hu, Robert Moffitt. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015.

[9]. Marukawa, Tomoo. “Regional Unemployment Disparities in China.” Economic Systems, vol. 41, no. 2, June 2017, pp. 203–14. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2016.11.002.

[10]. “Subsidising Stability: State Employment in China.” VoxDev, voxdev.org/topic/institutions-political-economy/subsidising-stability-state-employment-china.

[11]. Zheng, Hongyun, et al. “Working Hours and Job Satisfaction in China: A Threshold Analysis.” China Economic Review, vol. 77, Feb. 2023, p. 101902. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101902.

[12]. Francisc Betti, “How China’s shifting industries are reshaping its long-term growth model, ” World Economic Forum, June 28, 2024, https: //www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/06/how-china-s-shifting-industries-are-reshaping-its-long-term-growth-model/

[13]. C. Textor, “Number of college and university graduates in China 2013-2023, ” Statista, May 31, 2024, https: //www.statista.com/statistics/227272/number-of-university-graduates-in-china/#: ~: text=In%202023%2C%20a%20record%20high, education%20in%20the%20United%20States

[14]. Beishan Xiang, Huiying Wang, and Huimin Wang. “Is There a Surplus of College Graduates in China? Exploring Strategies for Sustainable Employment of College Graduates, ” Sustainability, 15, (2023): 15540. p. 2.

[15]. Yong Han, et al. “Supply and demand of higher vocational education in China: Comprehensive evaluation and geographical representation from the perspective of educational equality, ” PLOS ONE, 18, no.10. (2023): e0293132.

[16]. Zedong Han and Yun Wang, “Education signaling, effort investments, and the market's expectations: Theory and experiment on China's higher education expansion, ” China Economic Review, vol. 75, (Oct. 2022), https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101848

[17]. Yangqiao Zheng, Xiaoqi Zhang, and Yu Zhu, “Overeducation, major mismatch, and return to higher education tiers: Evidence from novel data source of a major online recruitment platform in China, ” China Economic Review, 66. (April 2021). https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101584

[18]. Dongli Liu, “2024 Blue-Collar Worker Development Report by Zhaopin, ” Sohu. June 7 2024, https: //www.sohu.com/a/784325961_121284943

[19]. Changheng Zhou, “Lying Flat’ and Rejecting the Rat Race: The Survival Anxiety of Chinese Youth, ” Science Insights, 41, no.7, (2022), p.741.

[20]. McVey, Frank L. “The Social Effects of the Eight-Hour Day.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 8, no. 4, Jan. 1903, pp. 521–30. https: //doi.org/10.1086/211157.

[21]. Remington, Thomas F., and Xiao Wen Cui. “The Impact of the 2008 Labor Contract Law on Labor Disputes in China.” Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, Aug. 2015, pp. 271–99. https: //doi.org/10.1017/s1598240800009371.