1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence, as the core engine of the new tech revolution, has become a strategic focus for major economies. The 2021 14th Five-Year Digital Economy Plan emphasized "deep AI-real economy integration," systematically reducing institutional costs via subsidies, standards, and ecosystem cultivation. Under AI policy guidance, technologies like intelligent financial systems and blockchain-based evidence storage have accelerated AI integration into enterprise management, providing institutional and technical support for improving accounting information quality.

From a practical perspective, corporate accounting disclosure faces structural challenges. Traditional financial processes rely on manual operations, leading to recurring issues like earnings management and misreporting. As enterprises grow and business complexity rises, disclosure delays and fragmentation worsen, reducing transparency. Sun notes that automated processes may induce new "collusive behaviors," complicating information asymmetry [1]. These issues limit the decision-usefulness of accounting data, highlighting the urgency of improving quality amid digitization. Can AI policies address these challenges? Theoretically, they act through two pathways: reducing costs via subsidies and incentives, and encouraging intelligent algorithms in finance and fund management to control risks. Policy-driven systems like big data risk models also strengthen external oversight, compelling enterprises to optimize internal controls (e.g., data feedback mechanisms) [2]. While Sun shows AI improves disclosure by optimizing management and production, how policy incentives translate to accounting quality remains unclear [1].

This study tests whether AI policies enhance accounting quality via "internal control optimization" using a difference-in-differences model, further exploring heterogeneous effects. The findings enrich understanding of external policy impacts on accounting quality and provide evidence for refining AI policies and building intelligent financial governance.

2. Literature review and theoretical analysis

2.1. Literature review

Accounting information quality has long been studied, with factors categorized as internal governance and external regulation. Internally, Na and Chen show financial sharing reduces agency costs, improving quality [3]; Zhou et al. find aligned executive incentives suppress earnings manipulation [4]. Externally, Yang proves cross-departmental regulation reduces profit manipulation [5]; Hong and Li show government checks deter interest transfers via related-party transactions [6]; Xiang and Shen out that the joint credit granting system, through an inter-bank information sharing mechanism, compels enterprises to enhance financial transparency to access credit resources, providing new evidence for the improvement in accounting information quality from the perspective of financing constraints [7].

AI policy impacts enterprise governance in three ways: Firstly, reducing governance costs by enabling real-time monitoring of management behavior via AI systems [8]; Secondly, improving decision efficiency through blockchain smart contracts [9]; Thirdly, strengthening risk control via AI-based multi-dimensional monitoring systems [10].

From a policy economics perspective, AI policies reduce institutional costs, creating a "policy → technology diffusion → efficiency improvement" mechanism. AI's dynamic risk systems and anomaly detection algorithms provide "prevention → control → supervision" cycles, addressing traditional audit lags.

2.2. Theoretical analysis

2.2.1. The influence of AI policy on accounting quality

AI policies act through two paths: Firstly, signaling effects, where subsidies and tax incentives signal technological competitiveness, increasing market scrutiny and pressuring firms to improve disclosure accuracy; Secondly, resource empowerment, where AI tools (e.g., robotic process automation, blockchain) automate financial processes, reducing human errors and enabling tamper-proof data.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): AI policies improve enterprise accounting information quality.

2.2.2. Internal control mechanism

AI policies enhance accounting quality via internal control optimization. AI reduces adoption costs, enabling enterprises to modernize controls: AI audit systems monitor management decisions, machine learning models identify risks, and smart contracts automate compliance.Additionally, AI policies strengthen external regulation. Governments use big data platforms and blockchain for real-time monitoring, creating a "policy → regulation → internal control" feedback loop.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): AI improves accounting quality by enhancing internal control.

3. Research design

3.1. Data description and sample selection

We begin with an initial sample of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2012 to 2023, sourced from the CSMAR database. Following the common practice in existing literature, the initial sample undergoes the following screening steps: first, financial firms are excluded; second, companies labeled ST or *ST during the study period are removed; finally, firms with missing data on key variables are deleted.This yields a final sample of 35,662 firm-year observations. All data are winsorized at the 5% level at both tails to control for outliers.

3.2. Variable definitions

3.2.1. Explanatory variables

The specific AI policy examined in this paper is the "National Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zone." To date, China has established these Pilot Zones in 18 cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Hefei, Deqing, Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi'an, Jinan, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Suzhou, Changsha, Zhengzhou, Shenyang, and Harbin. Treat is a dummy variable that equals 1 if a firm is registered in a region where the AI policy was implemented, and 0 otherwise..Post indicates whether the observed year is a policy implementation year. If yes, Post = 1; otherwise, Post = 0. D = Treat × Post.

3.2.2. Dependent variable

The dependent variable is accounting information quality (Accquality).It is measured by discretionary accruals derived from the modified Jones model [11], and the absolute value is taken. A higher value signals stronger earnings management, implying a decline in accounting information quality.

3.2.3. Control variables

To control for potential factors affecting corporate accounting information quality and ensure the validity and reliability of the empirical model, this study refers to existing literature and selects the following control variables: Lev, TobinQ,BOARD,INDBOARD, SIZE, AUDIT,ROA, and AGE. Industry and year dummy variables are also included to control for their impacts on accounting information quality.Variable definitions are summarized in Table 1.

3.3. Model specification

To calculate the impact of AI policies on corporate accounting information quality, we employs a difference-in-differences model (DID) to test changes in accounting information quality for enterprises included in AI policy pilot programs. As shown in Model (1), if H1 holds, the interaction term Post×Treat's regression coefficient (α₁) is expected to be significantly negative, indicating that AI policies improve accounting information quality in pilot enterprises.

Where the subscripts “i” and “t” represent firm and year for each firm-year observation, and Accquality represents accounting information quality. D indicates AI policies, serving as the core explanatory variable in this study, with α₁ being the primary focus. Higher Accquality values indicate lower accounting information quality. A significantly negative α₁ implies AI policies significantly enhance accounting quality. C represents control variables, including debt-to-asset ratio (Lev), the value of firm(TobinQ),firm size (SIZE), size of the Board of Directors (BOARD), proportion of independent directors (INDBOARD) , whether audited by the Big Four (AUDIT), return on total assets (ROA), and firm age (AGE). year and industry denote year fixed effects and industry fixed effects, respectively. Additionally, to address potential clustering effects on standard errors, robust estimation is applied with clustering at the firm level.

|

Variable Name |

Variable Symbol |

Description |

|

Accounting Information Quality |

Accquality |

It is defined as the absolute value of discretionary accruals from the modified Jones model, with a higher value implying lower accounting information quality. |

|

AI Policy |

D |

Equals 1 if the firm meets the AI policy pilot criteria in the year the policy is implemented; otherwise, 0. |

|

Firm Size |

Size |

Ln( total assets). |

|

Debt-to-Asset Ratio |

Lev |

Total Liabilities at the End of the Period / Total Assets at the End of the Period. |

|

Tobin's Q |

TobinQ |

Market Value of the Firm / Total Assets at the End of the Period. |

|

Board Size |

BOARD |

Ln(Number of board members+1). |

|

Proportion of Independent Directors |

INDBOARD |

Number of Independent Directors / Total Number of Board Members. |

|

Whether Audited by Big Four |

AUDIT |

Equals 1 if the auditor is one of the Big Four accounting firms; otherwise, 0. |

|

Return on Total Assets |

ROA |

(The Net Profit of Firm / Average Total Assets) × 100%. |

|

Firm Age |

AGE |

Ln( the number of years since the firm’s first listing+1). |

4. Analysis of empirical results

4.1. Analysis of baseline regression

4.1.1. Analysis of descriptive statistics results

Table 2 shows that the mean value of Accquality (0.0614) exceeds its median (0.0437), indicating a right-skewed distribution with a standard deviation of 0.0561. The variable ranges from 0.004 to 0.213, revealing substantial cross-firm variation in accounting quality. The descriptive statistics for other control variables are consistent with prior literature and fall within conventional ranges.

4.1.2. Analysis of baseline regression

As shown in Column (2) of Table 3, the immediate effect of the policy (D) on Accquality is insignificant (coeff. = -0.0004). However, the effect becomes significantly negative at the 5% level after a one-period lag (coeff. = -0.0021), indicating that the policy's impact on accounting quality takes one period to materialize.

|

Variable |

Mean |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Min |

Max |

Number of Observation |

|

Accquality |

0.0614 |

0.0437 |

0.0561 |

0.00400 |

0.213 |

35662 |

|

D |

0.239 |

0 |

0.427 |

0 |

1 |

35662 |

|

INDBOARD |

0.376 |

0.364 |

0.0495 |

0.333 |

0.500 |

35662 |

|

LEV |

0.418 |

0.410 |

0.195 |

0.109 |

0.774 |

35662 |

|

SIZE |

22.26 |

22.09 |

1.177 |

20.46 |

24.74 |

35662 |

|

TobinQ1 |

1.925 |

1.601 |

0.956 |

0.955 |

4.521 |

35662 |

|

AUDIT |

0.0618 |

0 |

0.241 |

0 |

1 |

35662 |

|

ROA |

0.0367 |

0.0355 |

0.0469 |

-0.0739 |

0.125 |

35662 |

|

AGE2 |

10.50 |

9 |

7.711 |

1 |

25 |

35662 |

|

(1) |

(2) |

|

|

VARIABLES |

Accquality |

Accquality |

|

D |

-0.0004 |

|

|

(-0.38) |

||

|

L.D |

-0.0021** |

|

|

(-2.06) |

||

|

BOARD |

-0.0163*** |

|

|

(-4.99) |

||

|

INDBOARD |

-0.0196** |

|

|

(-1.98) |

||

|

LEV |

0.0324*** |

|

|

(11.66) |

||

|

SIZE |

-0.0026*** |

|

|

(-5.04) |

||

|

TobinQ1 |

0.0066*** |

|

|

(13.51) |

||

|

AUDIT |

-0.0039** |

|

|

(-2.41) |

||

|

ROA |

-0.1080*** |

|

|

(-10.00) |

||

|

AGE2 |

-0.0002** |

|

| Table 3. (continued) | ||

|

(-2.50) |

||

|

Constant |

0.0615*** |

0.1385*** |

|

(136.71) |

(10.34) |

|

|

Year Fix Effect |

NO |

YES |

|

Ind Fix Effect |

NO |

YES |

|

Observations |

35,662 |

29,971 |

|

R-squared |

0.061 |

0.099 |

Robust t-statistics in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

4.2. Robustness test

4.2.1. Parallel trends test

To validate the parallel trends assumption, we estimate a dynamic model. The results, presented in Column (1) of Table 4, show no significant differences in the pre-treatment trends (pre_3, pre_2), failing to reject the null hypothesis of parallel trends. A statistically significant divergence arises only in post_1, which reinforces the causal interpretation of a lagged policy effect found in our baseline results.

4.2.2. Propensity score matching

Certain firm characteristics may simultaneously influence the implementation of AI policies and corporate accounting information quality, thereby affecting the relationship between the two. To mitigate potential confounding factors that could distort the research conclusions, this study employs the propensity score matching (PSM) method to control for sample selection bias. After applying radius matching and 1:1 without replacement matching, the sample is re-estimated. According to the results in column (2)-(3) of Table 4, after radius matching, the impact coefficient of AI policies on accounting information quality is significant at the 5% level. After 1:1 without replacement matching, the impact of AI policies on accounting information quality is significant at the 10% level. This indicates that the research are robust.

4.2.3. Placebo test

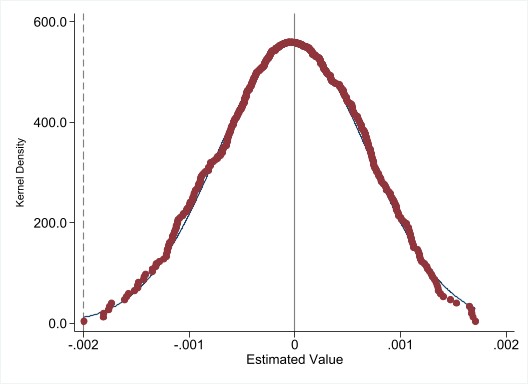

Since this study cannot fully control all factors affecting accounting information quality, particularly unobservable characteristics, which may influence the research conclusions, a placebo test is conducted. The study randomly samples the policy implementation 500 times and plots the distribution of the sampling coefficient estimates for the policy effect. As shown in Figure 1, the 500 regression coefficient estimates from random sampling are normally distributed around zero. The coefficient from the baseline regression (-0.0024) lies on the left side of the random coefficient distribution and is clearly distinct from the random estimates. This statistical pattern indicates that randomly assigned policy implementations do not affect accounting information quality. The observed improvement in accounting information quality under AI policies in this study is not due to random factors, demonstrating the statistical significance and robustness of the research conclusions.

4.3. Mechanism analysis

This study uses internal control effectiveness (nk) as the mediating variable and conducts an empirical test based on the internal control index system developed by Dibo Company. To mitigate data skewness effects, this study takes the natural logarithm of the index after adding 1 as a proxy variable for internal control effectiveness.To test H2, this study constructs Models (2) and (3) based on Model (1) for analysis.

The mediation analysis in Table 5 indicates that AI policies significantly enhance internal control effectiveness (coeff. = 0.0056, 1% level, Column (1). When both the policy and this mediator are included in Column (2), the effect of L.D on Accquality remains significant, supporting the conclusion that the policy improves accounting quality by strengthening the internal control environment. This enhances the standardization and transparency of financial reporting.

|

Parallel Trends Test |

Propensity Score Matching |

||

|

VARIABLES |

(1)Accquality |

(2)Accquality |

(3)Accquality |

|

pre_3 |

-0.0007 |

- |

- |

|

(-0.61) |

- |

- |

|

|

pre_2 |

-0.0016 |

- |

- |

|

(-0.95) |

- |

- |

|

|

current |

0.0016 |

- |

- |

|

(1.02) |

- |

- |

|

|

post_1 |

-0.0025* |

- |

- |

|

(-1.70) |

- |

- |

|

|

post_2 |

-0.0013 |

- |

- |

|

(-0.94) |

- |

- |

|

|

L.D |

- |

-0.0021** |

-0.0024* |

|

- |

(-2.06) |

(-1.93) |

|

|

BOARD |

-0.0145*** |

-0.0163*** |

-0.0150*** |

|

(-4.76) |

(-4.99) |

(-3.50) |

|

|

INDBOARD |

-0.0135 |

-0.0196** |

-0.0151 |

|

(-1.45) |

(-1.98) |

(-1.15) |

|

|

LEV |

0.0359*** |

0.0324*** |

0.0300*** |

|

(13.91) |

(11.65) |

(8.39) |

|

|

SIZE |

-0.0034*** |

-0.0026*** |

-0.0025*** |

|

(-7.08) |

(-5.04) |

(-3.93) |

|

|

TobinQ1 |

0.0059*** |

0.0066*** |

0.0078*** |

| Table 4. (continued) | |||

|

(12.80) |

(13.51) |

(12.49) |

|

|

AUDIT |

-0.0033** |

-0.0039** |

-0.0031* |

|

(-2.10) |

(-2.41) |

(-1.70) |

|

|

ROA |

-0.0750*** |

-0.1080*** |

-0.1682*** |

|

(-7.57) |

(-10.00) |

(-12.10) |

|

|

AGE2 |

-0.0003*** |

-0.0002** |

-0.0002** |

|

(-4.41) |

(-2.50) |

(-2.21) |

|

|

Constant |

0.1525*** |

0.1384*** |

0.1320*** |

|

(12.14) |

(10.34) |

(7.79) |

|

|

Year Fix Effect |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Ind Fix Effect |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Observations |

35,662 |

29,969 |

14,779 |

|

R-squared |

0.091 |

0.099 |

0.104 |

Robust t-statistics in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

4.4. Heterogeneity analysis

Results from the size-based subsample analysis (Table 5) reveal a stark contrast. The effect of the AI policy is significant and larger in magnitude for big firms (Column (3)) but negligible for small firms (Column (4)). This disparity indicates that larger firms, with their greater capacity to absorb and utilize policy support for AI investments, experience more substantial improvements in accounting quality. Smaller firms, however, appear constrained by the high costs and low returns of such technological adoption.

|

Mechanism Analysis: Internal Control |

Heterogeneity Analysis: Firm Size |

|||

|

VARIABLES |

(1)nk |

(2)Accquality |

(3)Big firm |

(4)Small firm |

|

L.D |

0.0056*** |

-0.0022** |

-0.0027** |

-0.0012 |

|

(2.76) |

(-2.17) |

(-2.09) |

(-0.82) |

|

| Table 5. (continued) | ||||

|

nk |

0.0262*** |

-0.0188*** |

-0.0119** |

|

|

(6.81) |

(-4.63) |

(-2.30) |

||

|

BOARD |

0.0111 |

-0.0162*** |

-0.0230* |

-0.0092 |

|

(1.55) |

(-4.91) |

(-1.86) |

(-0.58) |

|

|

INDBOARD |

0.0411* |

-0.0193* |

0.0254*** |

0.0385*** |

|

(1.85) |

(-1.93) |

(6.62) |

(9.91) |

|

|

LEV |

0.0139** |

0.0306*** |

-0.0027** |

-0.0012 |

|

(2.23) |

(10.82) |

(-2.09) |

(-0.82) |

|

|

SIZE |

0.0132*** |

-0.0028*** |

- |

- |

|

(11.55) |

(-5.40) |

- |

- |

|

|

TobinQ1 |

-0.0023*** |

0.0068*** |

0.0076*** |

0.0059*** |

|

(-2.60) |

(13.57) |

(9.68) |

(8.91) |

|

|

AUDIT |

0.0238*** |

-0.0045*** |

-0.0033* |

-0.0065* |

|

(6.37) |

(-2.72) |

(-1.85) |

(-1.89) |

|

|

ROA |

0.9406*** |

-0.1367*** |

-0.0682*** |

-0.1507*** |

|

(47.67) |

(-11.80) |

(-4.41) |

(-10.25) |

|

|

AGE2 |

-0.0007*** |

-0.0001** |

-0.0001 |

-0.0003*** |

|

(-5.15) |

(-2.01) |

(-1.26) |

(-2.64) |

|

|

Constant |

6.1036*** |

-0.0254 |

0.1603*** |

0.1339*** |

|

(204.91) |

(-0.90) |

(8.45) |

(4.55) |

|

|

Year Fix Effect |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Ind Fix Effect |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Observations |

29,277 |

29,277 |

16,002 |

13,969 |

|

R-squared |

0.203 |

0.101 |

0.104 |

0.104 |

Robust t-statistics in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

5. Conclusions

Drawing on a comprehensive dataset of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2012 to 2023, this study investigates the impact of artificial intelligence policies on corporate accounting information quality. The empirical analysis yields three principal conclusions. First, the implementation of AI policies demonstrates a significant capacity to enhance the quality of corporate accounting information, and this finding withstands a battery of robustness checks. Second, internal control functions as a significant mediating mechanism in the process through which AI policies improve accounting information quality. Third, the beneficial effect of AI policies on accounting information quality is particularly pronounced in the context of large-scale enterprises, likely due to their greater resource capacity and more established operational frameworks.

Overall, the findings confirm that AI policies enhance accounting quality, with internal control playing a mediating role and firm size acting as a critical contingency. This study thus supplies valuable empirical evidence on the policy-quality relationship and underscores the importance of technology-facilitated pathways for optimizing financial governance during digitalization.

References

[1]. Sun W, Zuo F. Artificial Intelligence and Accounting Information Disclosure Quality: From the Perspective of Internal Management and Production Efficiency [J]. Accounting Friend, 2025(10): 111–119.

[2]. Liu Y Y, Chen M, Li Z. The External Pressure Effect of Intelligent Supervision Systems on Enterprise Internal Control [J]. Accounting Research, 2021(4): 45–52.

[3]. Na C H, Chen X. The Impact of Financial Sharing on Accounting Information Quality: Governance or Agency? [J]. Accounting Research, 2024(09): 16–31.

[4]. Zhou L, Zhang J X, Zhou Pinghua. Executive Incentive Adjustments, Accounting Information Quality, and Stock Price Crash Risk [J]. Journal of Beijing Technology and Business University (Social Sciences Edition), 2024, 39(03): 108–121.

[5]. Yang F. Joint Accounting Supervision and Accounting Information Quality of Listed Companies: Evidence from the Joint Regulation by the Ministry of Finance and the CSRC [J]. Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, 2025(01): 16–27.

[6]. Hong J M, Li Y. Government Accounting Supervision and Corporate Related-Party Transactions: Evidence from the Ministry of Finance's Random Inspection of Accounting Information Quality [J]. Journal of Shanxi University of Finance and Economics, 2024, 46(10): 113–126.

[7]. Xiang R, Shen L. Joint Credit Granting System and Corporate Accounting Information Quality: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment [J]. Accounting Research, 2024(08): 19–31.

[8]. Cai C H, Li M. Global Governance of Artificial Intelligence: A Perspective from the Principal-Agent Theory [J]. Studies in International Politics, 2025(2): 45–58.

[9]. Wang G, Ye M, Zheng T J. Application of Blockchain Technology in Corporate Accounting from the Perspective of Information Quality [J]. Finance and Accounting, 2019(2): 67–69.

[10]. Zhao C, Wang F. Does "Internet +" Help Reduce Corporate Cost Stickiness? [J]. Financial Research, 2020(4): 112–125.

[11]. Dechow P M, Sloan R G.Hutton A P .Detecting Earnings Management [J].Accounting Review, 1995, 70(2): 193-225

Cite this article

Zhang,J. (2025). The Effect of Artificial Intelligence Policy on Enterprise Accounting Information Quality: An Empirical Study. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,235,7-16.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2025 Symposium: Data-Driven Decision Making in Business and Economics

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sun W, Zuo F. Artificial Intelligence and Accounting Information Disclosure Quality: From the Perspective of Internal Management and Production Efficiency [J]. Accounting Friend, 2025(10): 111–119.

[2]. Liu Y Y, Chen M, Li Z. The External Pressure Effect of Intelligent Supervision Systems on Enterprise Internal Control [J]. Accounting Research, 2021(4): 45–52.

[3]. Na C H, Chen X. The Impact of Financial Sharing on Accounting Information Quality: Governance or Agency? [J]. Accounting Research, 2024(09): 16–31.

[4]. Zhou L, Zhang J X, Zhou Pinghua. Executive Incentive Adjustments, Accounting Information Quality, and Stock Price Crash Risk [J]. Journal of Beijing Technology and Business University (Social Sciences Edition), 2024, 39(03): 108–121.

[5]. Yang F. Joint Accounting Supervision and Accounting Information Quality of Listed Companies: Evidence from the Joint Regulation by the Ministry of Finance and the CSRC [J]. Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, 2025(01): 16–27.

[6]. Hong J M, Li Y. Government Accounting Supervision and Corporate Related-Party Transactions: Evidence from the Ministry of Finance's Random Inspection of Accounting Information Quality [J]. Journal of Shanxi University of Finance and Economics, 2024, 46(10): 113–126.

[7]. Xiang R, Shen L. Joint Credit Granting System and Corporate Accounting Information Quality: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment [J]. Accounting Research, 2024(08): 19–31.

[8]. Cai C H, Li M. Global Governance of Artificial Intelligence: A Perspective from the Principal-Agent Theory [J]. Studies in International Politics, 2025(2): 45–58.

[9]. Wang G, Ye M, Zheng T J. Application of Blockchain Technology in Corporate Accounting from the Perspective of Information Quality [J]. Finance and Accounting, 2019(2): 67–69.

[10]. Zhao C, Wang F. Does "Internet +" Help Reduce Corporate Cost Stickiness? [J]. Financial Research, 2020(4): 112–125.

[11]. Dechow P M, Sloan R G.Hutton A P .Detecting Earnings Management [J].Accounting Review, 1995, 70(2): 193-225