1. Introduction

From classical mythology to Bible stories, the female body has been continuously visually transformed into an aesthetic object throughout Western art history. For centuries, male artists have produced a visual story through the male gaze, “his stories.” In their narratives centered around violence against women, male artists have used violence as aesthetics and the unfolding of "entertaining" narrative plots. Whether in Baroque painting in the 17th century or arbitrary modernist production in the 20th century, the expression of male painters continued to reinforce existing gender power. It is interesting to note that Rubens' and Picasso's works share similarities: women are depicted as passive bodies that lack autonomy. In contrast, women artists have represented women with subjectivity and resistance through mediums like painting, textiles, and fashion. A historical comparison of these images shows a complex process of the female body being suppressed, reshaped, and at times reclaimed. This paper argues that by comparing works from the 17th and 20th centuries, we can trace how male artists have aestheticized gender violence, while female artists have actively subverted this tradition by reasserting narrative agency and reclaiming the female body as a site of resistance.

2. Results

2.1. Gendered violence in 17th-century male art

2.1.1. Rubens and the aestheticization of sexual violence

Following the speed of religious reformation and political consolidation of power under the monarchy in 17th-century Europe, the Baroque era often came to express themes of conquest, destruction, and violence under the guise of morality and religious reconstruction - women are often depicted as targets of sexual violence in the Bible and mythology. For example, biblical scenes associated with sexual violence towards women include The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus and the abduction of The Rape of the Sabine Women. As Allison Kim discusses, religious and mythological subjects often provided a framework that normalized the visual depiction of sexual violence. In these visual messages, the nakedness of women was depicted as innocent under the guise of religious morals, allowing violence to be beautified as visual pleasure. In the works presented by Rubens, women were primarily depicted as passive victims. In both of these examples, the male artist masked the violent nature of the painting through a mastery of visual techniques that allowed the viewer to ignore the suffering of the women in the painting.

Peter Paul Rubens' painting The Rape of the Sabine Women exemplifies how Baroque painting maintained the visual character of gendered violence while allowing women to lose their subjectivity (fig. 1).

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-the-rape-of-the-sabine-women

The painting depicts Roman men forcing Sabine women to marry while it is full of chaos and drama - entangled bodies, flowing clothing, and twisted body placements. Although the women express fear, their resistance is not aggressive because the Rubens emphasize their softness rather than their pain. At the same time, Rubens enhances the scene through elegant composition: the diagonal composition and warm light transform the violence into a visually harmonious display, as this is the only way the violation depicted in the painting can be concealed [1].

For a further example of visualizing sexual violence in Rubens’s oeuvre consider The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (fig. 2).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rape_of_the_Daughters_of_Leucippus

This painting depicts the myth of Castor and Pollux raping Leucippus' daughter. In the center of the image depicting the abduction are two nude women whose pale, fat body forms juxtapose the strong, muscular bodies of the men. While the two women lift their arms in resistance there is neither aggression nor violence in their expressions or bodies; their suffering, an expressed body, is clouded in the elegantly erotic nature of the image as if the artist is tacit in the belief that women can only succumb to gender violence. The idealized version of the victims glorifies the moment of abduction. The painting does not pretend to show fear, pain, or aggression - it shows the artifice of scenery representing violence that appeals to desire created from pleasure. Rubens establishes a visual culture dominated by men that aestheticizes women's suffering in beauty and naturalizes sexual domination in mythical narratives.

2.1.2. Artemisia Gentileschi and women’s resistance

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes presents entirely the opposite version of gender violence - addressing women's resistance to patriarchal oppression, and in complement to Rubens's paintings (fig. 3).

https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/judith-beheading-holofernes

Based on Judith murdering Assyrian General Holofernes in the Bible, Gentileschi shifted away from sexiness and beauty and placed - determination - as the focus of the bodies, highlighting and expressing bodily struggle and emotion. Judith stabbed the sword into the left side of Holofernes' neck with her full might. Blood dyed the white sheets red without the audience, producing feelings of pleasure and revenge. Gentileschi's personal experience as a rape survivor provides the basis for the work's personal conviction [2]. Her Judith is not an ornamental heroine, but an agent of revenge and justice. While Rubens created paintings that portrayed female characters as victims in fancy dress, Gentileschi reclaimed the narrative discourse, depicting women as reliable actors and active participants in liberation.

Gentileschi's Susanna and the Elders also conspires to directly challenge the conventions of erotic subjects by deploying composition (fig. 4).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susanna_and_the_Elders_(Artemisia_Gentileschi,_Pommersfelden)

Many male versions of the story Victim Susanna are centered in the vision, whereas Gentileschi's Susanna in the middle of the image is misaligned, and Susanna's lower half is covered by a white cloth, distracting attention from the female figure, rather than the bare skin leaving room for reverie. The elders comprise the entire center axis of the painting and their aggressive physical posture overwhelms the composition, drawing the viewer's focus away from the victimized and to the victimizer. Additionally, since a significant part of the elder figures comprised the top of the composition, their position, looking down on Susanna mirrors the power of inequality inherent in the narrative. Gentileschi's decision not to represent Susanna as an object of pleasure, but as a persecuted subject, is what sets this painting apart from the rest in gallery spaces filled with male paintings.

2.2. Continuities of the male gaze in 20th-century art

2.2.1. Picasso’s Weeping Woman and the exploitation of trauma

From the 17th to the 20th centuries, the visual representation of women in male-dominated art changed, but not their function. During the Baroque period, mythological and biblical themes provided a cultural framework for artists who eroticized female suffering and rendered violence as a spectacle of beauty. By the 20th century, artistic styles had evolved - while realism gave way to cubism and surrealism, the female body remained at the center of violence, was vulnerable, and was still used to project male desire, anxiety, or trauma. Violence became less literal and more symbolic, often embedded in disjointed images and distorted anatomy. The male gaze carries through both eras, recasting female suffering as a formal innovation.

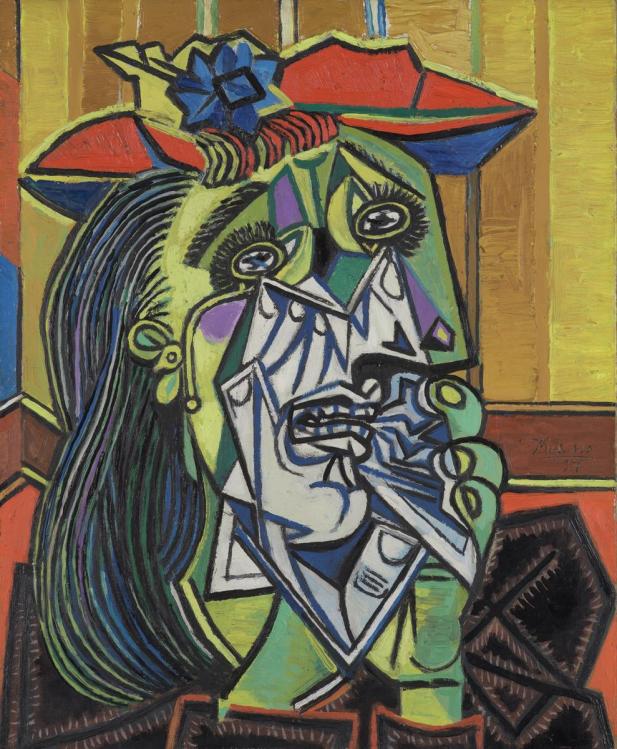

Pablo Picasso's Weeping Woman is often interpreted in the media as a symbol of grief over war and political suffering, but the painting also carries deep gender implications (fig. 5).

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/picasso-weeping-woman-t05010

The figure in the painting is recognized as Dora Maar - Picasso's lover, muse, and talented artist - and she is depicted in the painting as a fragmented, agonized figure: her features are disintegrated into jagged planes, and her mouth is frozen in a scream. The painting transforms the emotional breakdown of the woman into an object of display and masks individual grief with propaganda of political suffering. Significantly, Picasso's relationship with Maar was fraught with emotional manipulation and psychological abuse, with reports of physical violence between the two, and Dora herself later remarked, “All the portraits he painted of me were lies.” [3] This context suggests that the work may express not only collective trauma but also the artist's pain in appropriating real women for visual and emotional effects. Like many male artists before him, Picasso transformed the female body and psyche into material - not to reveal the inner world of women, but to express Picasso's morbid inner world.

2.2.2. Hans Bellmer’s dolls and fetishized violence

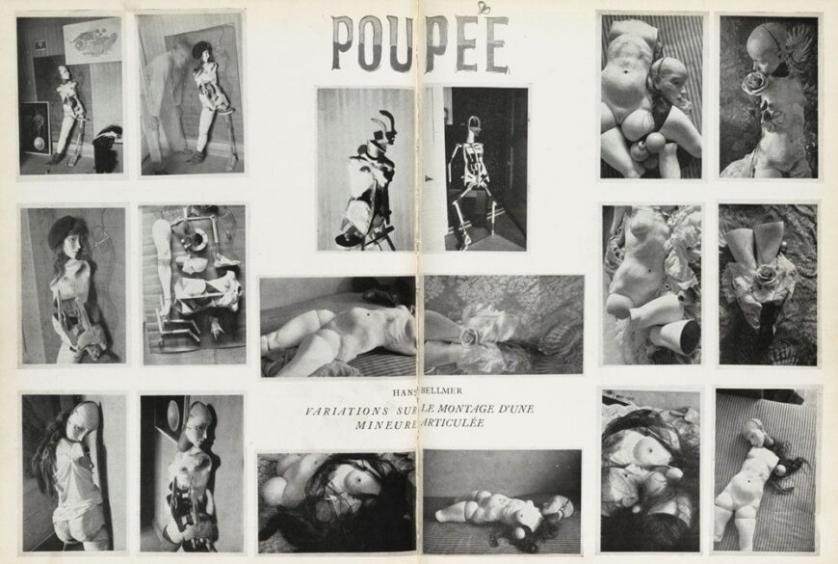

Hans Bellmer's La Poupée series is one of the most visceral images of gender violence in 20th-century art (fig. 6).

https://smarthistory.org/hans-bellmer-the-doll/

The dolls are lifelike, with interchangeable limbs, mutilated torsos, twisted joints, and the faces of adolescent girls whose bodies have been manipulated, divided, and fetishistically rearranged. Far from being innocent surrealist games, Bellmer reflects through his work a disturbing psychological landscape in which the female body becomes a site of desire and erotic violence. “Bellmer repeatedly recreates the experience of violence through his doll-creations ... They become fetishes in the second sense: compensatory objects for his castration fantasy ... The dolls help Bellmer maintain desire.” [4] It is thus clear that Bellmer's treatment of the female body is a projection of sadistic desire, merging aesthetic experimentation with a desire for mastery. The dolls' bound poses and overexposed genitalia reduce them to mute, passive objects of control, and Bellmer undoubtedly pushes the historical tradition of objectifying and violently treating women to grotesque extremes.

2.3. Female artists’ reclamation of narrative agency

2.3.1. Teresa Margolles: textiles as memory and collective resistance

At the same time, current women artists drew upon real-world trauma to engage with and subvert long-established visual traditions in objectifying women. Teresa Margolles is an example of this practice of employing trauma, and using blood-stained fabrics taken from the bodies of female victims to record the female body while moving it from being a passive object of display to a site of memory, and resistance (fig. 7).

![Figure 7. Teresa Margolles, Tela bordada [Embroidered Fabric], 2012. Traditional Mayan embroidery on fabric by indigenous activists from Guatemala, 202 × 206 cm. Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa.](https://file.ewadirect.com/press/media/markdown/document-image7_HyxOkIE.jpeg)

https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/teresa-margolles/

In Julia Skelly's article "Hard Touch: Gore Capitalism and Teresa Margolless's Soft Interventions", she describes Margolles's textile-based work as “soft interventions”, which she uses to respond to gender-based violence through the tactile and bodily trace of materials [5]. The blood-drenched cloths, later embroidered by groups of women, become a mode of assignation to commemorative images and collective acts of resistance through labor. Margolles does not aestheticize or metaphorize the trauma, she presents the wounds and blood from actual bodies. Unlike scholars and artists like Bellmer or Picasso, who fragmented, abstracted, or emotionalized the female figure, Margolles offers corporeal reality and material evidence of bodily pain. She foregrounds emotionality and political solidarity between women, and textiles become home for resistance, eventually, a bearer of collective consciousness, and a way to engage with violence head-on.

2.3.2. Nan Goldin: photography as an autobiographical witness

Nan Goldin's photography represents one of the most intuitive vision approaches in contemporary art - one that meets gender violence challenges head-on in ways that others could not. She uses her camera to document up close her own body, emotional relationships, and traumatic experiences, which form the autobiographical works she creates. In Nan One Month After Being Battered, she looks squarely into the viewer's eyes, her face swollen with bruises and her eyes puffed, a pure image of the aftermath of intimate partner violence (fig. 8).

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/goldin-nan-one-month-after-being-battered-p78045

In this image, there are no layers of metaphor or embellishment, only direct visual evidence. Unlike the objectification of the female body explored in the works of Bellmer or Picasso, Golding reinterprets the theme of violence against women by directly showing her wounded face, instead of letting the audience spy on her trauma. Golding is both the muse, the subject of the image of the victim of violence, and the narrator of the picture. By using the self as the center of expression, she further disrupts the narrative logic of traditional art in which the Other shapes the protagonist. In addition, Golding's photographic works turn the camera to the inescapable violence itself, allowing the audience to face the costs of women in terms of gender-based violence and physical and mental aggression so that the condemnation intention behind his works is more obvious. It can be said that Goldin has transformed the suffering he has experienced into a visual language of resistance, care, and survival, encouraging countless women who have suffered violence to face their trauma, whether on the outside or inside.

3. Conclusion

Representations of gender violence in art history reveal a long visual tradition rooted in the male gaze, in which the female body is constantly aestheticized and objectified to serve the emotional and symbolic needs of patriarchal narratives. From Peter Paul Rubens to surrealist artists such as Hans Bellmer and Pablo Picasso, women have often existed not as subjects, but as projected vessels of male desire, anxiety, and control. Over the centuries, however, women artists have continued to disrupt this visual structure, reclaiming narrative power through radically different creative strategies. Whether it is Artemisia Gentileschi's fierce portrayal of justice, Teresa Margolles' testimonies to the trauma of reality, or Nan Goldin's in-your-face presentation of private suffering, these works reveal the deep costs of violence and give voice to resistance from the wounds themselves. These works do not consume or glorify pain but rather ask the viewer to acknowledge, remember, and confront the violence itself. In a sense, the history of gender-based violence against women in visual representations of art is not a single thread; rather, it is more like a tapestry woven together by male artists. Women artists have been silent within it, but are now reclaiming their voices. This “tapestry” of women will only be truly broken when women choose to reiterate their experiences and perspectives.

References

[1]. Carroll, Margaret D. “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence.” Representations 25 (January 1, 1989): 3–30. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2928464.

[2]. Cohen, Elizabeth S. “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History.” Sixteenth Century Journal 31, no. 1 (March 1, 2000): 47–75. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2671289.

[3]. Caws, Mary Ann. Dora Maar With & Without Picasso: A Biography, 2000.

[4]. El-Sioufi, Dina A. “Hans Bellmer and the Experience of Violence.” UCL Discovery, November 2005. https: //discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1444661/.

[5]. Skelly, Julia. “Hard Touch: Gore Capitalism and Teresa Margolles’s Soft Interventions.” H-ART Revista De Historia Teoría Y Crítica De Arte, no. 6 (2020): 24–41. https: //doi.org/10.25025/hart06.2020.03.

Cite this article

Sheng,W. (2025). Gendered Violence and Female Rebellion in 17th- and 20th-Century Art. Communications in Humanities Research,77,112-121.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Consciousness and Cognition in Language Acquisition and Literary Interpretation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Carroll, Margaret D. “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence.” Representations 25 (January 1, 1989): 3–30. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2928464.

[2]. Cohen, Elizabeth S. “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History.” Sixteenth Century Journal 31, no. 1 (March 1, 2000): 47–75. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2671289.

[3]. Caws, Mary Ann. Dora Maar With & Without Picasso: A Biography, 2000.

[4]. El-Sioufi, Dina A. “Hans Bellmer and the Experience of Violence.” UCL Discovery, November 2005. https: //discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1444661/.

[5]. Skelly, Julia. “Hard Touch: Gore Capitalism and Teresa Margolles’s Soft Interventions.” H-ART Revista De Historia Teoría Y Crítica De Arte, no. 6 (2020): 24–41. https: //doi.org/10.25025/hart06.2020.03.