1. Introduction

Global urbanization has intensified the pressure on peri-urban green spaces. It makes it increasingly difficult to balance development and conservation. The UK’s Green Belt policy which was introduced after WWII to curb urban sprawl has historically been effective. However, it is at the center of debate due to housing shortages and growing infrastructure demands. For example, Bishop [1] found that policy discussions often reduce the Green Belt to a "land bank". The economic rationale for Green Belt development is mixed. Although supporters are highlighting housing shortages, national data suggest that there is only a weak link between land supply and affordability. The housing crisis is most severe in London and the Southeast. At the same time, Green Belts provide essential benefits such as carbon storage, biodiversity protection, and recreational opportunities, but development risks are eroding these functions. It often disproportionately affect vulnerable groups and potentially undermine community well-being despite economic growth. Stakeholder theory reinforces that planning must take all affected groups into account [2] and recognize diverse priorities from economic growth to environmental protection.

In this study, the dilemma is exemplified in a fictional High Vale case. With 68% of its land designated as Green Belt, the region faces development constraints with post-industrial decline and population growth. The proposal is to build a film studio on protected land, which highlights tensions between economic revitalization and environmental protection. This paper analyzes the High Vale case to explore trade-offs and strategies for sustainable development, addressing four research questions: (1) What factors drive development in High Vale's Green Belt?; (2) What are the key stakeholder positions and conflicts? (3) What are the potential impacts and trade-offs? (4) What strategies can balance growth and conservation?

2. Research methodology: a case study of high vale

This study adopts a case study approach to examine the High Vale Film Studio Project, a method well suited to exploring complex planning issues by linking theory with practice [3]. The scenario highlights tensions between economic development, environmental protection, and social values, exposing dynamics that statistics alone cannot reveal. It also illustrates stakeholder theory in practice: assessing actors through power, legitimacy, and urgency shows how local communities, despite limited authority, can influence outcomes, while official bodies may hold power but less influence [4]. Framing the case through academic module scenarios provides a coherent narrative and supports the use of stakeholder mapping, SWOT analysis, and impact assessment [3,4].

The study is based on desktop research, drawing on module scenarios and literature on Green Belt policy, urban planning, and stakeholder theory. A multi-method framework strengthens analysis. Stakeholder salience theory [4] identifies key actors, while SWOT analysis evaluates strengths and weaknesses against opportunities and threats. Considering environmental, social, and economic impacts reflects how planning decisions balance competing demands. Together, this framework supports analysis of High Vale’s complex challenges.

3. Findings and analysis

3.1. Key drivers for the proposed development

The High Vale Film Studio is driven by the urgent need to address post-industrial decline and reduce reliance on London, as residents face limited local opportunities, with higher earners commuting and most jobs confined to retail and services (BPLN0086 Scenario, p.1). Supporters argue the studio would create high-quality creative industry jobs, curb economic leakage, and diversify the local economy, reflecting wider evidence that urban growth projects can stimulate regeneration [5]. However, it risks constraining land supply and worsening housing affordability [6], a pressing concern in areas of deprivation. The governance landscape is complex: national devolution shifts from a two-tier to a unitary authority, generating uncertainty while pressuring growth delivery (BPLN0086 Scenario, p.2). National policy favors development, but the local Council Leader, Caroline Forest, must honor her manifesto pledge to protect the Green Belt (BPLN0086 Scenario, p.3), exemplifying tensions between growth targets and local accountability and highlighting the need for flexible, context-specific urban strategies [7]. Population growth further intensifies housing and infrastructure demand, with 130,000 residents, ethnic diversity, and deprivation (BPLN0086 Scenario, p.1). Supporters suggest the studio could fund infrastructure and expand opportunities, yet risks remain that development could disproportionately affect vulnerable groups and deepen divisions. Balancing immediate economic, social, and policy pressures with long-term protection of Green Belt land is therefore critical, emphasizing the need for conditional, equitable, and adaptive planning approaches.

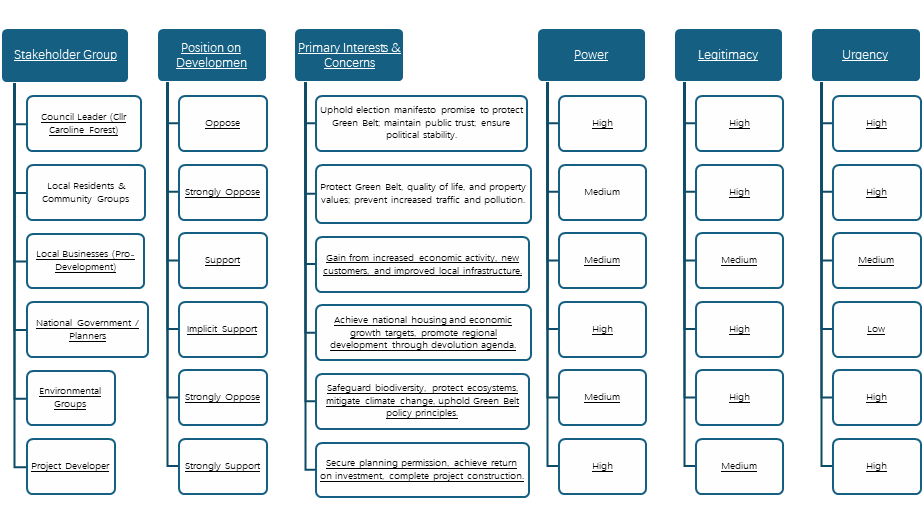

3.2. Stakeholder analysis and conflicting perspectives

The Film Studio proposal activates a network of stakeholders with divergent interests and varying degrees of influence, shaped by their power, legitimacy, and urgency [4]. Figure 1 maps these key actors and their positions, revealing the core conflicts. The analysis reveals a critical governance stalemate. High-power, high-legitimacy stakeholders are in direct conflict: the Council Leader's commitment to conservation clashes with the Planning Cabinet Member's and National Government's growth agendas. This creates a "shear zone" where economic, environmental, and social priorities intersect and conflict, making a decision that satisfies all parties nearly impossible [8].

3.3. Analysis of key conflicts

The High Vale project reveals two major governance tensions. First, a conflict exists between short-term economic gains and long-term environmental protection. Supporters, such as developers, emphasize job creation and investment, while opponents, including community groups and Councillor Forest, argue that the project sacrifices the Green Belt and violates sustainability principles. Second, local democratic accountability clashes with regional development pressures. While local representatives are mandated to protect the Green Belt, national policies push councils to prioritize economic growth and housing, often forcing a reconsideration of protected land. These tensions highlight the fundamental challenge of balancing local interests with national agendas and environmental sustainability.

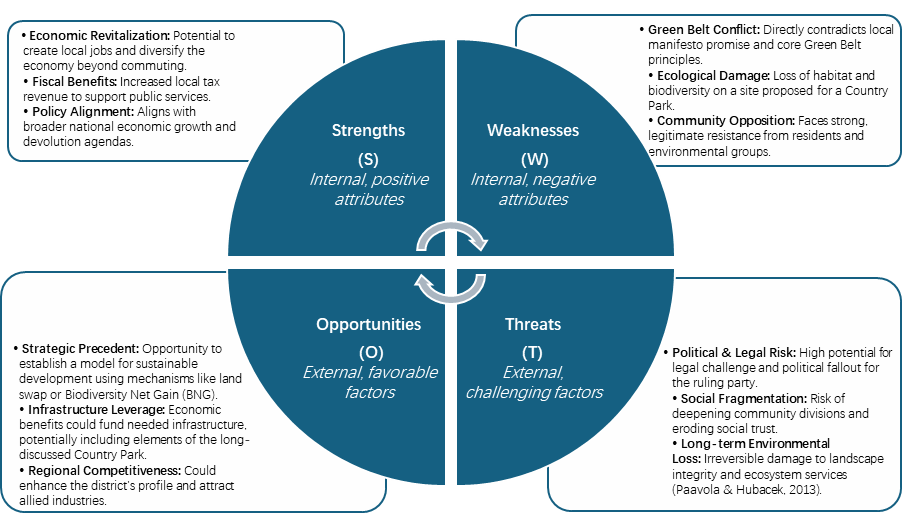

3.4. SWOT analysis of the high vale film studio project

A SWOT analysis, illustrated in Fig. 2 below, synthesizes the internal and external factors influencing the project's viability. This framework helps move beyond a binary debate by systematically outlining the strategic situation. The SWOT analysis confirms that the project's path is fraught with significant risks that must be actively managed. Its viability hinges on leveraging opportunities like BNG to offset profound weaknesses and threats, particularly the ecological and social costs.

3.5. Assessment of potential impacts

3.5.1. Environmental impacts

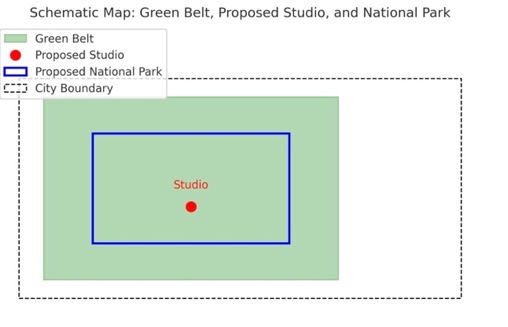

The development poses severe and potentially irreversible environmental risks due to its location on Green Belt land earmarked for a Country Park. The conversion of this greenfield site would lead to direct habitat loss and landscape fragmentation. As Andrén [9] established, habitat fragmentation can lead to a non-linear collapse in biodiversity once a critical threshold is passed. Furthermore, replacing permeable green space with impermeable infrastructure would diminish the area's carbon sequestration capacity, a critical ecosystem service in mitigating climate change [10]. Figure 3, a schematic map of the proposed development area, visually underscores the proximity of the site to ecologically sensitive areas and the threat of habitat intrusion.

3.5.2. Socio-economic impacts

The project presents a dualistic socio-economic outcome. On one hand, it promises short-term economic gains through job creation and local investment, consistent with theories that link urban growth to economic stimulation [5]. On the other hand, it risks long-term negative consequences. An influx of workers could increase housing demand, exacerbating affordability issues in a district with existing deprivation (BPLN0086 Scenario, p.1) [6]. Moreover, the highly contentious nature of the project, as evidenced by the stakeholder analysis, threatens to polarize the community, erode public trust in the council, and undermine social cohesion. The decision-making process itself, especially if perceived as pre-determined or ignoring local voices, could cause lasting damage to democratic legitimacy.

4. Discussion: navigating the trade-offs and strategic pathways

4.1. The inevitability of trade-offs in Green Belt governance

This analysis of the High Vale case corroborates a central tenet of planning theory. Sustainable development involves fundamental trade-offs, particularly within the contested space of Green Belt policy [1]. The study shows that no solution can simultaneously maximize economic, environmental, and social benefits, echoing critiques of the triple bottom line [8]. The core tension in High Vale, between the economic regeneration agenda supported by the developer and Cllr Davidson, and the environmental protection mandate championed by the Council Leader and community groups, exemplifies these "shear zones". The case illustrates how trade-offs manifest in specific political and administrative contexts, such as a district council under two-tier governance facing imminent restructuring (BPLN0086 Scenario, 2024), affirming that decision-making is a value-laden process requiring explicit prioritization.

4.2. Reconciling theory and practice in collaborative planning

The stakeholder analysis reveals a significant gap between the collaborative planning theory and the realities of local governance. While theory emphasizes inclusive engagement to build trust and legitimacy [2], challenges posed by power imbalances are exposed in the High Vale scenario. The high salience of both supporting and opposing stakeholders [4] ends in a stalemate that it cannot be resolved by sole consultation. This study contributes to critical discourse on participation by showing that community influence (high legitimacy and high urgency) can be neutralized by powerful supporters. Moreover, higher-level policy agendas unless deliberate mechanisms rebalance influence. It underscores that dialogue quality, even with advanced tools, depends on facilitation and is often overlooked in procedural planning [11].

4.3. Towards conditional and adaptive strategies

Apart from identifying conflicts, this study proposes a framework for conditional and adaptive strategies tailored for the High Vale project. Although Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) has been promoted to reconcile development with conservation [12], its application often faces scrutiny over enforcement and long-term efficacy. This analysis discusses that BNG or similar mechanisms, like land swaps [13], must be embedded within a broader governance framework. This includes differentiated land management based on robust ecological assessment and institutional capacity for strong oversight [12]. The contribution emphasizes bundling technical solutions with governance preconditions, such as independent monitoring and regional cooperation, to prevent environmental compensation from becoming a tick-box exercise.

4.4. Theoretical and practical implications for reform

The High Vale case study shows that reforming Green Belt policy requires moving beyond simplistic binaries of protection vs development. The findings challenge the view of the Green Belt as a mere "land bank" [1]. They highlight its multifaceted role in local identity, political mandates, and ecological networks. Theoretical implications show that many factors are essential for sustainable outcomes, such as adaptive governance, integrating ecological protection, genuine public co-design, and strategic policy innovation. Practically, planners should institutionalize early and meaningful public participation through citizens' juries. They also need to mandate and rigorously enforce a "net gain" principle to advocate cross-boundary collaborative frameworks.

5. Conclusion

This study explores the complex tensions surrounding development within UK Green Belt policy. It addresses its research questions by showing how development pressures in High Vale arise from economic necessity, policy shifts favoring growth, and social demands linked to a growing population. The analysis revealed a fundamental conflict between stakeholders prioritizing short-term economic growth and those emphasizing long-term environmental protection. Potential outcomes highlight trade-offs, such as job creation and fiscal benefits versus ecological loss, increased housing pressures, and community divisions. It is concluded that although it is not a perfect solution with balancing development and conservation, it manages trade-offs through transparent, accountable and adaptive governance. Sustainable outcomes require moving beyond a simple “protection versus development” choice toward adaptive governance that combines conditional policies, genuine public collaboration, and strong oversight. Navigating Green Belt development demands transparent, accountable, and strategic decision-making that prioritizes long-term sustainability. Future research should extend these findings through empirical studies and cross-regional comparisons.

References

[1]. Bishop, P., Perez Martinez, A., Rogemma, R. and Williams, L., 2020. Repurposing the green belt in the 21st century. UCL press.

[2]. Greenwood, M.R. and Simmons, J., 2004. A stakeholder approach to ethical human resource management. Business & Professional Ethics Journal, 23(3), pp.3-23.

[3]. Breslin, M. and Buchanan, R., 2008. On the case study method of research and teaching in design. Design Issues, 24(1), pp.36-40.

[4]. Mitchell, R.K., Agle, B.R. and Wood, D.J., 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of management review, 22(4), pp.853-886.

[5]. Voith, R.P. and Wachter, S.M., 2009. Urban growth and housing affordability: The conflict. The Annals of the American academy of political and social science, 626(1), pp.112-131.

[6]. Kallergis, A., Angel, S., Liu, Y., Blei, A.M., Sanchez, N. and Lamson-Hall, P., 2022. Housing affordability in a global perspective. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

[7]. SDSN, 2013. Why the world needs an urban sustainable development goal.

[8]. Jeurissen, R., 2000. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business.

[9]. Andrén, H., 1997. Habitat fragmentation and changes in biodiversity. Ecological bulletins, pp.171-181.

[10]. Paavola, J. and Hubacek, K., 2013. Ecosystem services, governance, and stakeholder participation: an introduction. Ecology and Society, 18(4).

[11]. Schroth, O., Hayek, U.W., Lange, E., Sheppard, S.R. and Schmid, W.A., 2011. Multiple-case study of landscape visualizations as a tool in transdisciplinary planning workshops. Landscape Journal, 30(1), pp.53-71.

[12]. Knight-Lenihan, S., 2020. Achieving biodiversity net gain in a neoliberal economy: The case of England. Ambio, 49(12), pp.2052-2060.

[13]. Natoli, S.J., 1971. Zoning and the development of urban land use patterns. Economic Geography, 47(2), pp.171-184.

Cite this article

Fan,Z. (2025). Balancing Development and Conservation: A Critical Analysis of the High Vale Film Studio Project and Its Implications for Green Belt Policy. Communications in Humanities Research,94,101-107.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art, Design and Social Sciences

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bishop, P., Perez Martinez, A., Rogemma, R. and Williams, L., 2020. Repurposing the green belt in the 21st century. UCL press.

[2]. Greenwood, M.R. and Simmons, J., 2004. A stakeholder approach to ethical human resource management. Business & Professional Ethics Journal, 23(3), pp.3-23.

[3]. Breslin, M. and Buchanan, R., 2008. On the case study method of research and teaching in design. Design Issues, 24(1), pp.36-40.

[4]. Mitchell, R.K., Agle, B.R. and Wood, D.J., 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of management review, 22(4), pp.853-886.

[5]. Voith, R.P. and Wachter, S.M., 2009. Urban growth and housing affordability: The conflict. The Annals of the American academy of political and social science, 626(1), pp.112-131.

[6]. Kallergis, A., Angel, S., Liu, Y., Blei, A.M., Sanchez, N. and Lamson-Hall, P., 2022. Housing affordability in a global perspective. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

[7]. SDSN, 2013. Why the world needs an urban sustainable development goal.

[8]. Jeurissen, R., 2000. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business.

[9]. Andrén, H., 1997. Habitat fragmentation and changes in biodiversity. Ecological bulletins, pp.171-181.

[10]. Paavola, J. and Hubacek, K., 2013. Ecosystem services, governance, and stakeholder participation: an introduction. Ecology and Society, 18(4).

[11]. Schroth, O., Hayek, U.W., Lange, E., Sheppard, S.R. and Schmid, W.A., 2011. Multiple-case study of landscape visualizations as a tool in transdisciplinary planning workshops. Landscape Journal, 30(1), pp.53-71.

[12]. Knight-Lenihan, S., 2020. Achieving biodiversity net gain in a neoliberal economy: The case of England. Ambio, 49(12), pp.2052-2060.

[13]. Natoli, S.J., 1971. Zoning and the development of urban land use patterns. Economic Geography, 47(2), pp.171-184.