1. Introduction

Social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube have revolutionized digital entertainment through algorithm-driven recommendation systems, infinite scroll interfaces, and visually immersive content. These design strategies, optimized by artificial intelligence to maximize engagement, stimulate frequent dopamine release and encourage compulsive use [1,2]. While these mechanisms sustain user attention, many individuals report feeling emotionally empty or mentally fatigued after extended sessions—sometimes within only thirty minutes of continuous scrolling [3]. This paradox, in which high engagement coexists with post-use exhaustion, raises important questions about the cognitive and emotional consequences of short-video consumption.

Previous studies have established that short-video addiction is driven by interface features such as infinite scroll and variable reward schedules that induce a state of “flow”—a psychologically immersive condition characterized by deep focus and temporal distortion [2,4]. However, the current study’s results demonstrate that the sense of fatigue users experience cannot be explained solely by the amount of time spent on these platforms. The duration of viewing sessions did not significantly predict post-use fatigue, whereas content repetitiveness and homogeneity, particularly exposure to videos from the same creator, emerged as robust predictors of boredom and exhaustion. This suggests that the quality of the algorithmic feed—its diversity and novelty—plays a more critical role than the quantity of screen time in shaping users’ emotional outcomes.

Theoretically, these findings refine existing models of instant gratification and flow by indicating that user fatigue arises not from temporal overexposure but from cognitive saturation caused by repetitive stimuli. Practically, they underscore the need for platform designers and policymakers to shift from time-based metrics of “digital wellness” toward measures of algorithmic diversity and content variation. This study identifies the structural and algorithmic factors underlying user exhaustion, offering new evidence for more ethical and psychologically sustainable content recommendation systems.

2. Literature review

The theoretical foundation for this study draws upon the concepts of instant gratification and flow theory. Instant gratification explains the behavioral reinforcement loop created by immediate rewards, while flow theory describes deep immersive states characterized by temporal distortion and intrinsic motivation [5]. Together, these frameworks help explain how immersive, reward-rich environments such as short-video platforms sustain engagement while depleting mental and emotional resources.

A particularly relevant body of work is the literature on message fatigue. So, Kim, and Cohen [6] defined message fatigue as a psychological state of “exhaustion and boredom” resulting from overexposure to repetitive messaging. Their experimental findings demonstrated that as fatigue rises, attention declines and counterarguing increases, thus undermining engagement. Kim and So [7] extended this framework by showing that message fatigue reduces persuasive effectiveness through the mediating effects of reactance and inattention. A recent meta-analysis further confirmed that message fatigue consistently predicts decreased engagement and increased message resistance [8]. Collectively, these studies establish fatigue as a motivational state that actively impedes attention and engagement.

Research on short-video addiction further illuminates how platform design interacts with cognitive mechanisms to produce both addiction and exhaustion. Studies have shown that infinite scrolling and algorithmic recommendations sustain user engagement through variable reward schedules that stimulate dopamine pathways [1,4]. Chen, Li, and Wang [9] found that short-form video addicts exhibit shorter fixation durations, poorer concentration, and greater attentional difficulty than non-addicted users. Similarly, Chiossi, Weller, and Garbacea [10] demonstrated that rapid context switching in short-video feeds significantly impairs prospective memory and intention retention. Liao [11] reviewed the psychological mechanisms of short-video addiction and argued that algorithmic curation, fast-paced switching, and visual overstimulation lead to cognitive overload and dependency. These findings indicate that addiction mechanisms extend beyond behavioral reinforcement to include attentional depletion, dopamine desensitization, and emotional weariness.

Despite this progress, several gaps remain. Most existing studies emphasize addiction and engagement rather than post-use fatigue or emotional aftermath. Duration of use has been the dominant explanatory variable, while content repetition and diversity have received limited attention. Algorithmic and sensory design features—such as color saturation, redundancy, and recommendation homogeneity—are rarely linked directly to user fatigue outcomes. This study therefore pivots from the addiction framework to explore post-use fatigue as a distinct psychological outcome. Specifically, it investigates how algorithmic curation and content repetition contribute to boredom and exhaustion, thereby bridging the gap between platform design and user emotion.

To address these theoretical and practical questions, this study focuses on three research questions:

• RQ1: Do users of different genders and age groups experience different levels of fatigue after exposure to repetitive short-video content?

• RQ2: Does the duration of exposure to algorithmically recommended content predict self-reported fatigue?

• RQ3: Does reduced content diversity contribute to increased fatigue?

3. Method

A quantitative cross-sectional online survey was developed to test the proposed research questions. The survey instrument comprised three main components: demographic information, usage patterns, and a psychometric scale assessing post-use fatigue. The demographic section included questions about gender, age, and occupation. The usage section measured typical session duration and frequency of short-video consumption. The final section evaluated post-use fatigue through a series of Likert-scale items adapted from validated message fatigue and media fatigue scales [6,12]. Respondents rated their agreement with statements reflecting emotional exhaustion, boredom, and mental fatigue (e.g., “After watching, I feel mentally drained”) on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

The survey was distributed via online channels and social media groups over a four-week period, resulting in 152 valid responses. Of these, 78 participants (51.3%) identified as female and 74 (48.7%) as male. Respondents were distributed across five age categories: 18–24 years (n = 35), 25–30 years (n = 42), 31–40 years (n = 45), 41–50 years (n = 20), and 50 years or older (n = 10). The sample included students, professionals, and freelancers, ensuring a diverse representation of typical short-video users.

To examine RQ1, an independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare fatigue scores between genders, and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine differences across age groups. A two-way ANOVA tested potential interaction effects between gender and age. For RQ2 and RQ3, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess the effects of session duration and content diversity on self-reported fatigue. The first model tested session duration as a single predictor, while the second model incorporated both duration and content diversity to evaluate their independent and combined contributions. All analyses were two-tailed with α = .05 and were conducted using R (version 4.3).

4. Result

4.1. Demographic differences in boredom and fatigue

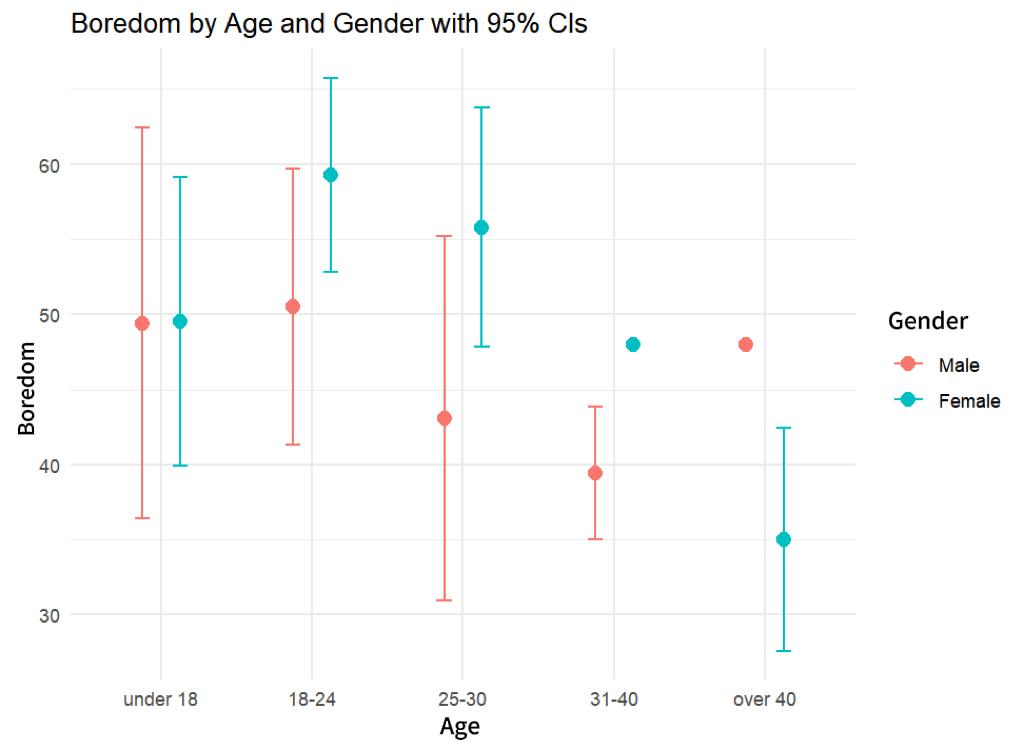

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to examine gender differences in boredom levels. Results indicated a statistically significant difference between male and female users, t(150) = −2.28, p = .024. On average, male users (M = 5.59) reported slightly lower boredom scores than female users (M = 5.99). The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference ranged from −0.75 to −0.05, suggesting that the observed gender effect, though small, is reliable. Thus, the null hypothesis of no gender difference was rejected.

A one-way ANOVA was used to test whether boredom levels differed across five age groups. The effect of age was statistically significant, F(4,147) = 4.54, p = .0017, indicating that boredom levels vary by age. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (Tukey HSD) revealed that participants aged 31–40 reported significantly lower boredom levels than those aged 18–24 (p = .02), and participants over 40 reported significantly lower levels than both 18–24-year-olds (p < .01). No other pairwise contrasts reached significance. Overall, boredom levels showed a decreasing trend with increasing age.

A two-way ANOVA examined the combined effects of gender and age on boredom. Both gender (F(1,142) = 5.32, p = .023) and age (F(4,142) = 4.89, p = .001) showed significant main effects, but their interaction was not significant (F(4,142) = 1.17, p = .33). This indicates that the gender gap in boredom remained relatively consistent across age categories. Descriptive and graphical analyses (see Figure 1) further support these findings: boredom levels generally decreased with age for both genders, with male users showing slightly lower boredom than females across all age groups. Wider confidence intervals among younger participants suggest greater variability in boredom experiences during early adulthood.

4.2. Predictors of boredom and fatigue

Table 1. Linear regression to test whether content from the same author or repetitive content will lead to feeling fatigue on rednote.

|

Feeling bored/fatigue when finish using |

|

|

Intercept |

8.34*** |

|

Content from same author |

5.84*** |

|

Repetitive content |

2.05* |

|

Multiple R-squared: 0.4597 F-statistic: 63.4 *** |

|

To test RQ2, a regression model was estimated with session duration as a predictor of post-use fatigue. Results showed that time duration did not significantly predict users’ feelings of boredom or fatigue, F = 1.41, p = .23, R² = .0093. Session length accounted for less than 1% of the variance in fatigue, indicating that longer exposure does not directly translate into greater exhaustion. This finding rejects the assumption that fatigue is a simple byproduct of screen time, suggesting that other experiential or algorithmic factors drive post-use emotional outcomes.

To test RQ3, a multiple regression analysis was conducted including two predictors: exposure to repetitive content and exposure to content from the same author. The model was statistically significant, F = 63.4, p < .001, with R² = .46, indicating that nearly half of the variance in fatigue could be explained by content homogeneity. Both predictors were significant: content from the same author (β = 5.84, p < .001) and repetitive content (β = 2.05, p < .05). The larger effect of “same author” exposure suggests that fatigue is intensified not only by thematic repetition but also by lack of diversity in source and presentation style.

Taken together, these results indicate that content homogeneity—rather than time spent—is the critical factor driving post-use fatigue. Users’ sense of boredom and exhaustion appears to result from cognitive saturation and limited novelty within algorithmically curated feeds, rather than from the sheer duration of media exposure.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide important refinements to existing theories of instant gratification, flow, and digital fatigue. The most striking result is that the duration of a viewing session did not significantly predict user fatigue (p = .23), contradicting conventional assumptions that “screen time” is the main driver of emotional exhaustion. Instead, fatigue emerged primarily from content repetitiveness and homogeneity, particularly from repeated exposure to videos by the same author. This indicates that the cognitive and affective outcomes of social media use depend more on the structural properties of algorithmic recommendation systems than on the quantity of use.

These findings contribute to theoretical models in two key ways. First, they challenge the linear temporal logic embedded in the instant gratification model, which assumes that fatigue accumulates with exposure time. The current data instead support a qualitative model of fatigue, in which emotional exhaustion arises from the saturation of similar cognitive stimuli rather than from time itself. Second, the results extend the concept of flow by suggesting that continuous exposure to uniform content traps users in a pseudo-flow state—one that sustains attention but suppresses novelty, thereby eroding intrinsic motivation and generating fatigue upon exit.

From a design perspective, these findings implicate algorithmic curation as a primary driver of user exhaustion. Repetitive exposure to content from the same authors narrows users’ informational and creative horizons, reinforcing algorithmic “filter bubbles” that limit diversity. Over time, such homogeneity may desensitize users to stimulation, producing emotional numbness and cognitive fatigue even in the absence of prolonged use. This aligns with prior concerns that AI-based recommendation systems prioritize engagement metrics at the expense of user well-being [1,4].

The demographic findings offer additional nuance. The significant gender and age effects suggest that younger and female users are more susceptible to fatigue, possibly due to higher emotional attunement and self-referential engagement patterns on social platforms [13]. The absence of an interaction effect between gender and age implies that these patterns operate independently across demographic lines.

Taken together, the results reveal that the emotional costs of algorithmic engagement are driven more by content homogeneity than by time-based exposure. This insight reframes how digital wellness should be conceptualized. Rather than promoting time-reduction interventions (e.g., “screen time limits”), platforms and policymakers should prioritize content diversity interventions—for example, by adjusting recommendation algorithms to include greater thematic, stylistic, and source variety. Doing so could break cycles of cognitive monotony and promote more balanced engagement.

Future research should examine the psychological mechanisms mediating this relationship, such as boredom proneness, attentional depletion, and reward desensitization. Experimental and longitudinal designs could further validate whether increasing content diversity mitigates fatigue or restores intrinsic motivation in short-video environments. Ultimately, these findings underscore that sustaining user well-being in algorithmic media ecosystems requires a paradigm shift: from measuring how long users stay, to understanding how content diversity shapes how they feel when they leave.

6. Conclusion

This study examined the psychological and algorithmic determinants of post-use fatigue among short-video platform users. By integrating theories of instant gratification and flow with empirical survey data, it identified content homogeneity instead of screen time as the primary driver of emotional exhaustion. Although gender and age predicted modest differences in fatigue, the duration of use did not. Instead, exposure to repetitive content and videos from the same author strongly predicted boredom and mental fatigue, accounting for nearly half of the variance in post-use exhaustion. These results reveal that the emotional toll of short-video consumption stems less from how long users engage and more from what they repeatedly encounter within algorithmic feeds.

The findings contribute to theoretical discussions of digital fatigue by refining the traditional instant gratification model. Rather than viewing fatigue as a linear consequence of overexposure, this study highlights cognitive saturation as the underlying mechanism of exhaustion. Users are not necessarily drained by time itself, but by the predictable and monotonous structure of algorithmically curated experiences that erode novelty and engagement quality. This reconceptualization bridges psychological theories of flow and media fatigue, demonstrating that continuous exposure to uniform stimuli creates a paradoxical state of engagement without fulfillment.

Practically, these insights call for a reorientation of digital well-being strategies. Current interventions often emphasize time management, encouraging users to monitor or limit screen time, but this research suggests that such measures may be insufficient. Efforts to enhance digital wellness should instead focus on content diversity and algorithmic transparency, ensuring that recommendation systems incorporate variability in style, source, and theme. By prioritizing heterogeneity over engagement maximization, platforms could reduce the emotional weariness that characterizes much of short-video consumption today.

Future research should expand on these findings using longitudinal or experimental designs to isolate the causal pathways between content repetition, cognitive overload, and emotional outcomes. Qualitative and neuroscientific approaches could further illuminate how algorithmic curation interacts with individual psychological traits such as boredom proneness or reward sensitivity. Ultimately, sustaining user well-being in algorithmic media environments requires moving beyond simplistic notions of “screen time” toward a more nuanced understanding of algorithmic experience quality—how the structure of digital engagement, not merely its duration, shapes the modern psychology of fatigue.

References

[1]. De, R., Mishra, S., & Gupta, S. (2024). Algorithmic engagement and affective exhaustion: A study of short- video platform design. Computers in Human Behavior, 157, 107414.https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.107414

[2]. Boston University Journal of Public Health. (2021). Hooked on dopamine: How social media keeps us scrolling. Boston University School of Public Health. https: //www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2021/hooked-on-dopamine-how-social-media-keeps-us-scrolling/

[3]. Chauhan, A. (n.d.). Why social media leaves you feeling empty. Psychology Today.https: //www.psychologytoday.com/

[4]. Liao, Y. (2023). Flow, instant gratification, and the addictive dynamics of short-video platforms. Journal of Media Psychology, 35(4), 230–242.

[5]. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

[6]. So, J., Kim, S., & Cohen, H. (2017). Message fatigue: Conceptual definition, operationalization, and correlates. Journal of Health Communication, 22(7), 593–600. https: //doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1339140

[7]. Kim, S., & So, J. (2018). How message fatigue decreases effectiveness: Examining the mediating roles of reactance and inattention. Journal of Communication, 68(3), 454–478. https: //doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy013

[8]. Meta-Analytic Evidence on Message Fatigue. (2024). Communication Research Review, 8(1), 15–32.

[9]. Chen, J., Li, Z., & Wang, T. (2022). The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(1045), 1–10.https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1045116

[10]. Chiossi, F., Weller, J., & Garbacea, M. (2023). The effect of context switching in short-form video consumption on user cognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 7(CSCW), 1–17. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3579504

[11]. Liao, Y. (2024). The psychological mechanisms of short video addiction: A review and perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1391204. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391204

[12]. Mao, Y., Zhang, Y., & Li, Z. (2022). Understanding social media fatigue: A multidimensional analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944481. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.944481

[13]. Wang, L., & Yuan, F. (2025). Cognitive depletion and attentional dispersion in algorithmic media environments. Human Communication Research, 51(1), 45–63.

Cite this article

Song,Y. (2025). Not How Long, But What You See: Repetition and Fatigue in Short-Video Consumption. Communications in Humanities Research,91,55-61.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICIHCS 2025 Symposium: Literature as a Reflection and Catalyst of Socio-cultural Change

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. De, R., Mishra, S., & Gupta, S. (2024). Algorithmic engagement and affective exhaustion: A study of short- video platform design. Computers in Human Behavior, 157, 107414.https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.107414

[2]. Boston University Journal of Public Health. (2021). Hooked on dopamine: How social media keeps us scrolling. Boston University School of Public Health. https: //www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2021/hooked-on-dopamine-how-social-media-keeps-us-scrolling/

[3]. Chauhan, A. (n.d.). Why social media leaves you feeling empty. Psychology Today.https: //www.psychologytoday.com/

[4]. Liao, Y. (2023). Flow, instant gratification, and the addictive dynamics of short-video platforms. Journal of Media Psychology, 35(4), 230–242.

[5]. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

[6]. So, J., Kim, S., & Cohen, H. (2017). Message fatigue: Conceptual definition, operationalization, and correlates. Journal of Health Communication, 22(7), 593–600. https: //doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1339140

[7]. Kim, S., & So, J. (2018). How message fatigue decreases effectiveness: Examining the mediating roles of reactance and inattention. Journal of Communication, 68(3), 454–478. https: //doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy013

[8]. Meta-Analytic Evidence on Message Fatigue. (2024). Communication Research Review, 8(1), 15–32.

[9]. Chen, J., Li, Z., & Wang, T. (2022). The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(1045), 1–10.https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1045116

[10]. Chiossi, F., Weller, J., & Garbacea, M. (2023). The effect of context switching in short-form video consumption on user cognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 7(CSCW), 1–17. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3579504

[11]. Liao, Y. (2024). The psychological mechanisms of short video addiction: A review and perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1391204. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391204

[12]. Mao, Y., Zhang, Y., & Li, Z. (2022). Understanding social media fatigue: A multidimensional analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944481. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.944481

[13]. Wang, L., & Yuan, F. (2025). Cognitive depletion and attentional dispersion in algorithmic media environments. Human Communication Research, 51(1), 45–63.