1. Introduction

Past research has demonstrated that being married or in an intimate relationship is positively associated with individuals’ well-being [1]; but the long-term stability of such a relationship remains uncertain. For example, scholars estimate that approximately 42-45% of U.S. marriages would end in divorce [2,3]. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China [4], the number of registered divorces increased from 2.84 million in 2021 to 3.61 million in 2023. This global rise in divorce reflects the increasing challenges individuals face in maintaining intimate relationships and underscores the importance of identifying key contributing factors.

While many factors, such as types of love, investment, commitment, self-esteem, and self-disclosure, may influence relationship satisfaction [5], one important yet underexplored contributor is the motivation for entering the relationship in the first place. In this study, we conceptualize motivation as the locus of control underlying behaviors [6] and define relationship satisfaction as the overall self-evaluation of one’s relationship status and quality [7]. Individuals may begin a relationship due to parental pressure, fear of loneliness, or financial insecurity–but how do such initial motives shape dyadic relationship satisfaction over time in more established relationships? As entry motives are the starting point, they are expected to influence what follows.

Specifically, these motives will be assessed within Self-Determination Theory (SDT), a metatheoretical framework that places reasons for action on a controlled–autonomous continuum. On the controlled side are reasons like “I have to” or “people expect me to”, and on the autonomous side are reasons like “I want to” or “this fits my values” [8,9]. Building on this, those motives will be classified into six subgroups, ranging from least to most autonomous: amotivation (lack of motivation to engage in a behavior); external regulation (acting to avoid punishment or obtain rewards); negative introjected regulation (acting to avoid negative feelings–e.g., guilt or shame–or to comply with internalized obligations); positive introjected regulation (acting to enhance one’s self-worth); identified regulation (acting because the individual finds it personally meaningful); and intrinsic regulation (acting because it is inherently satisfying) [6].

Blais et al. [8], studying 63 French-Canadian couples, introduced Perceived Adaptive Couple Behaviors–defined as one’s perception of adaptive behaviors in a dyadic relationship, including consensus, cohesion, emotional expression, problem-solving, and coping mechanisms. They found that more self-determined motives for staying in a relationship predicted more positive perceptions of adaptive interaction patterns, which in turn promoted higher dyadic happiness. In contrast, a recent six-month longitudinal study [6] showed that higher intrinsic motives to pursue romantic relationships predicted people’s likelihood of entering a relationship but were not significantly associated with relationship quality during that period.

Although these two studies seem to reach different conclusions, they differ in important ways. First, the former introduced a mediator. Second, relationship duration was shorter in the latter study, suggesting that both mediation processes and relationship duration should be considered. Third, the types of motivation are subtly different, in that the former is motivation for staying in a relationship, while the latter is motivation for pursuing a relationship. Obviously, the former is continuous and ongoing, whereas the latter reflects a more initial decision and aligns more closely with the motivation that we plan to examine in the present study.

Additionally, Patrick et al. [10] showed that when individuals experience greater need fulfilment, they are more likely to endorse autonomous reasons for being in a romantic partnership, thereby enhancing satisfaction. Their findings highlight a clear pathway from need fulfilment to motivation to satisfaction. Notably, Patrick’s study regarded motivation for being in a relationship as a mediator, rather than an independent variable. Furthermore, another critical preceding parameter–perhaps even before need fulfilment–may be the willingness to satisfy a partner’s needs. That is, individuals must first hold the intention to support their partner before their partner’s needs can be truly fulfilled.

Consequently, this study examines the extent to which entry motives are associated with relationship satisfaction among heterosexual Chinese couples. To obtain a more precise understanding, we will also examine willingness to meet partners’ needs as a mediator, where needs are defined as basic psychological requirements that support psychological growth, integrity, and flourishing [10,11]. The reason for using willingness as a mediator is that a more autonomous entering motivation may directly increase the individuals’ willingness to voluntarily benefit their partners, leading to more need fulfilment and thus higher partner satisfaction [9,10,12].

Moreover, self-esteem will be treated as a confounder to test whether the focal association between motivation and satisfaction is spurious. Building on Judge et al. [13], core self-evaluations–with self-esteem as the central component–are linked to more autonomous goal-setting at work and in broader life contexts, implying that self-esteem may be positively associated with autonomous motivation in intimate relationship contexts. Additionally, Erol & Orth [14] reported that self-esteem is positively related to satisfaction within relationships. Taken together, these findings suggest that people high in self-esteem typically sustain autonomous entry motives from the outset of their intimate relationships, and that relationship satisfaction may be enhanced directly by high self-esteem. As such, we will control for both partners’ self-esteem when estimating the motivation → willingness → satisfaction path. In this study, we will mainly focus on explicit self-esteem (ESE) of both partners. Although implicit self-esteem (ISE) is better at revealing individuals’ unconscious self-evaluation in a way that eliminates impression management [15], and may more strongly confound participants’ motives and satisfaction, we exclude it here. This is because common ISE measures–such as the Name-Letter Test and the Implicit Association Test–show limited validity [16], and we aim to avoid overcomplicating the model.

Ideally, the self-esteem scores used to estimate the self-esteem → motivation path should be the ones at the time when dyads started their relationship. However, the self-esteem values from several years ago can be hard to collect and low in reliability due to recall biases (i.e., memory bias). Meanwhile, it has been demonstrated that self-esteem is relatively stable and less contingent on everyday events for young and middle-aged adults [14,17]. As such, the current self-esteem scores will be employed to estimate both the ESE → motivation and ESE → satisfaction paths.

By identifying these correlations, this study may offer insights for individuals who are seeking intimate companionship, helping them increase self-awareness, reflect on their intentions before committing, and ultimately improve their marital and overall life satisfaction.

2. Present work

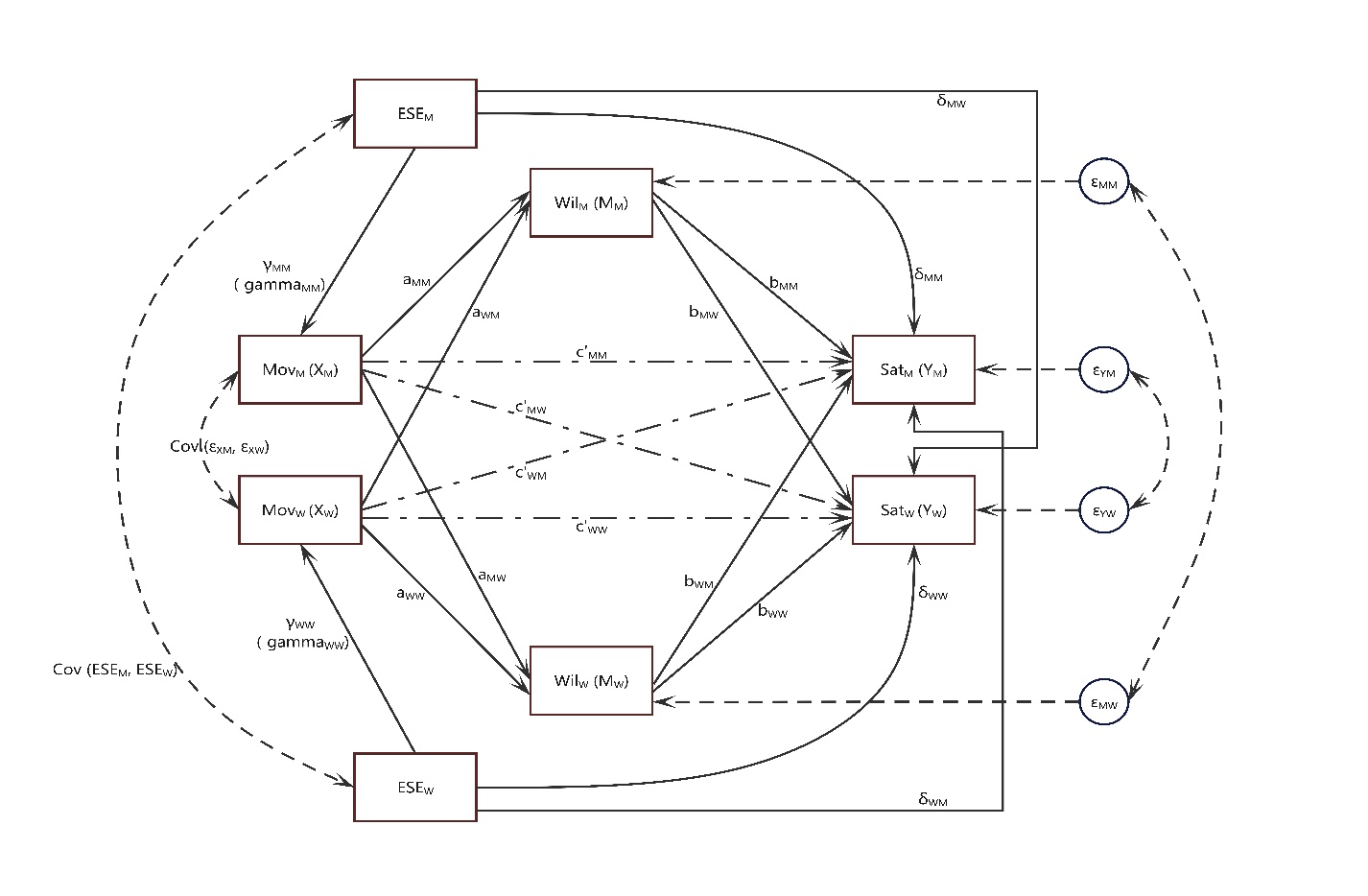

Note. Subscripts follow a predictor-target order, e.g., aWM denotes the path XW → MM, bMW denotes MM → YW, and c’WM denotes XW → YM. Solid single-headed arrows denote mediation paths (X → M, M → Y) as well as covariate paths from ESE to X and Y. Dash-dot single-headed arrows denote the direct X → Y path. Curved double-headed dashed arrows denote covariances (e.g., Cov (XM, XW), Cov (εYM, εYW), Cov (ESEM, ESEW)). Rectangles indicate measured variables; small circles indicate residuals.

The aim of the present research is to investigate the correlation between individuals’ motivation for entering a relationship and the relationship satisfaction of their own and their partners, controlling for both partners’ self-esteem. During the process, the mediating effect of both partners’ willingness to satisfy their partner’s needs will be tested as well.

To study this, heterosexual Chinese couples, aged 25 to 40, who have been together for 5 to 10 years, will be recruited. By setting these limits, we hope to control the variances of sexual orientation, participants’ age, and length of relationship to reduce their potential influences on relationship satisfaction. The reason we focus on couples being together 5-10 years is that the effects of entering motives on relationship satisfaction may be significantly accumulated and more detectable in mid- to longer-term relationships. The participants will be guided to complete a series of surveys to assess their motivation, willingness, self-esteem, and relationship satisfaction.

Since the interactions and responses within couples are likely correlated (e.g., if one is more willing to satisfy their partner’s need, the other will be motivated and satisfy back in return), we adopt the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) for data processing and analysis in this study [18,19]. To test mediation, we employ the actor-partner interdependence mediation model (APIMeM) as an extension of standard APIM [20,21].

For data analysis, details on modelling self-esteem as a confounder are provided in the Data Analytic Approach section.

3. Method

We will disclose all measures, exclusions, and procedures. We will obtain Institutional Review Board approval for human participants, comply with all requirements, and obtain written informed consent from all participants.

Participants. After considering the potential dropout and invalid responses, 300 heterosexual couples (300 males, 300 females; age = 25-40 years, relationship length = 5-10 years) from China will be recruited through social media, in exchange for an electronic red packet with a random amount of money (within RMB 5-10). Those participants who fail to complete the survey or provide invalid answers will be excluded. Each dyad will be treated as one sample.

For estimating the sample size, we set all aactor = 0.3 (i.e., as shown in Figure 1, aMM = aWW = 0.3), apartner = 0.1 (aMW = aWM = 0.1), bactor = 0.2, bpartner = 0.3. The use of equality constraints reflects a gender-invariance assumption on symmetric partner paths. Power analysis will be conducted with the R package semPower [22]. Significance of the indirect effects will be tested with 95% bias-corrected bootstrap intervals computed from 5,000 dyadic resamples [23].

For the actor indirect effect (Xi → Mi → Yi), where actor indirect = aactorbactor = 0.06, the analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.90) yielded N = 259 dyads. For the partner indirect effect (Xi → Mj → Yj), where partner indirect = apartnerbactor = 0.02, the analysis yielded N = 1,070 dyads. A post hoc analysis for partner indirect effect at N = 260 yielded actual power = 0.32, indicating insufficient power to detect this small effect. Accordingly, the partner indirect effect will be treated as exploratory.

3.1. Study design

Motivation for entering the relationship. The Autonomous Motivation for Romantic Pursuit Scale (AMRPS) will be used [6]. Because the original version of the scale is in English, it will be translated into Chinese with basic checks, and back-translation will be employed to ensure accuracy. This scale includes 24 items, with four items for each motivation type, such as “I entered the relationship because it would make the people close to me happy” for external regulation and “I felt good being in the relationship” for intrinsic regulation. Participants will be asked to answer each item in response to the prompt, “Thinking back to the initial stage of your current romantic relationship, why did you start it?”. Items are rated on a 1-5 scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

Willingness to meet partner’s needs. The Compassionate Goals Scale (CGS) will be used, as it focuses on supporting others without expectation of reciprocity and uniquely targets prosocial intention among all other relevant prosocial orientation measures [24,25]. Similarly, a translation-back-translation procedure will be adopted for this measure to ensure linguistic validity. Twelve items, each beginning with the prompt “In my romantic relationship, I try to...,” with examples like “Do things that benefit both of us” and “Refrain from acting in a selfish or self-focused way”. Responses range from 1 to 5, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

Relationship Satisfaction. The 32-item Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI) will be used [26]. The Chinese version of the CSI has demonstrated valid psychometric [7]. In the scale, item 1 (“please rate the overall degree of your relationship satisfaction.”) will be rated on a 0-6 scale (0 = lowest, 6 = highest), whereas the remaining 31 items will be rated on a 0-5 scale (0 = lowest, 5 = highest). Additionally, for items 26 to 32, semantic differential scales with bipolar adjectives on either end (e.g., enjoyable vs. miserable for item 32) will be used. Moreover, six items (6, 10, 15, 27, 29, and 31) are reverse-scored.

Explicit Self-Esteem. We will use the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [27] to measure explicit self-esteem, as its reliability and validity across many languages and cultures, including Mandarin, have been supported despite interpretive ambiguity for item 8 in some cultures [28]. In this measure, 10 items will be rated on a 1-4 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree).

Procedures. The Participating dyads will complete this online cross-sectional survey in the following sequence: 1) CGS-12; 2) AMRPS-24; 3) RSES-10; 4) CSI-32. The reason for placing CSI-32 at the end is to avoid its potential interference with the other three scales. The remaining three scales are presented out of conceptual order to reduce the likelihood that participants infer the research purpose and respond with social desirability.

To ensure the reliability of their answers, two additional attention checks will be added as the 27th and 54th questions, in which the first checker will ask participants to choose the “3” among 1-6, and the second will ask participants to choose the last option. As such, there will be 80 questions in total, which will require approximately 10-12 minutes to complete. Demographic information, such as gender, age, and relationship length, will be collected after participants complete all scales to avoid priming effects.

Before the survey, participants will be briefly instructed about the rules and reminded to answer independently. Moreover, a paired code and unique link will be employed to minimize partners’ interaction during the survey. The surveys with any two or more of the following features will be considered invalid and excluded from data analysis: 1) failure on one or both attention checks; 2) survey completion time within 5 minutes or over 20 minutes; 3) extreme response patterns (e.g., selecting the first option for all questions). After the survey, a debriefing will be given to thank participants and to explain the real purpose of this research.

Data Analytic Approach. The APIMeM will be employed to handle the interdependent dyadic data and examine associations among actor variables, partner outcomes, and the potential mediating process. The actor variable, in this context, refers to the variable related to oneself, and the partner variable refers to the variable related to one’s partner. Analyses will be carried out in lavaan under a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework [29], as SEM is a good fit for dealing with cross-partner residual covariances. Finally, all variables will be centered at the grand mean.

3.2. Distinguishability

Since the dyads recruited for this study are heterosexual, partners will be treated as distinguishable by gender in the APIMeM, with separate actor and partner paths for women and men. We do not hypothesize gender differences; therefore, we do not plan to conduct tests of indistinguishability at this stage, and all focal effects (actor/partner direct and indirect paths) will be estimated in the distinguishable model. However, if needed at the analysis stage (e.g., for parsimony or model stability), we may report an exploratory equality-constrained comparison in supplementary materials.

3.3. Mediation structure and equations

For each partner’s willingness, there will be two mediational paths. Using the man’s willingness as an example, the two paths are: XM → MM (actor effect) and XW → MM (partner effect). For each partner’s satisfaction, there are two direct paths and four indirect paths. For the man’s satisfaction, the two direct paths include: XM → YM (actor effect) and XW → YM (partner effect). The four indirect paths are: XM → MM → YM (actor-actor effect); XM → MW → YM (partner-partner effect); XW → MW → YM (actor-partner effect), and XW → MM → YM (partner-actor effect). As a result, the equations for willingness and satisfaction, without considering confounding effects, could be expressed as:

Here, ε denotes residuals (other factors that are not considered in the present research but could influence results); a indexes X → M, b indexes M → Y, and c’ indexes X → Y paths.

3.4. Confounding by Explicit Self-Esteem (ESE)

When it comes to estimating confounding effects, for the ESE → X (γ) paths, only the actor effect will be considered. This is because motives are defined as the locus of control underlying behavior [6] and cannot be directly observed or assessed by the partner, suggesting a much stronger connection with one’s own self-esteem than with the partner’s (i.e., one’s perceptions of their partner are filtered through one’s own self-views). As a robustness check, we will additionally estimate an alternative model including ESEpartner → Xactor (i.e., ESEW → XM; ESEM → XW); inferences for the focal paths will be compared and reported in the supplementary materials. As for the ESE → Y (δ) paths, both actor and partner effects will be considered, because those with higher self-esteem typically interact less defensively with their partners, thereby promoting partners’ satisfaction, which suggests a non-negligible partner effect. The mediators (i.e., willingness) are not considered to be confounded by self-esteem either, as no evidence from past work has shown a linkage between them. Accordingly, the overall effects of all variables, combined with mediating effects, can therefore be expressed as:

In addition, as shown in Figure 1, corresponding dyad residuals are allowed to covary (i.e., ESEW↔ESEM, εXW↔εXM, εMW↔εMM, εYW↔εYM). We will encode these equations in lavaan and fit them to the collected data to estimate the effects of all paths.

4. Results

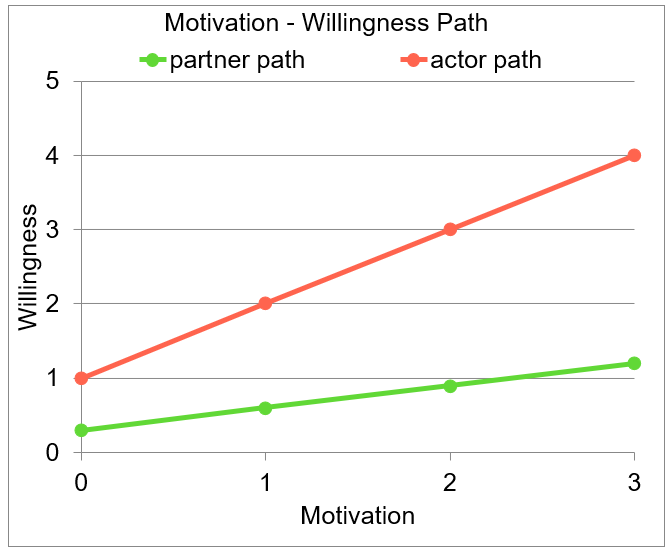

Motivation → Willingness Path. According to Patrick et al. [10], when individuals experience greater personal need fulfilment, they are more likely to hold autonomous reasons for being in a relationship. If individuals with greater willingness indeed meet their partner’s needs to a greater extent, such that their partners perceive greater need fulfilment, and if individuals with more autonomous entering motives tend to maintain their motives for staying in their relationship, we can predict that entering motivation for individuals is positively correlated with their willingness to satisfy their partner.

In contrast, the actor's entry motivation may still have a positive influence on their partner’s willingness to meet their needs, but with a smaller magnitude. This is because the association between the actor’s motivation and the partner’s willingness is more indirect. For example, a partner may tend to satisfy the actor’s needs in return when their own needs are met first, rather than being directly encouraged by the actor’s motivation.

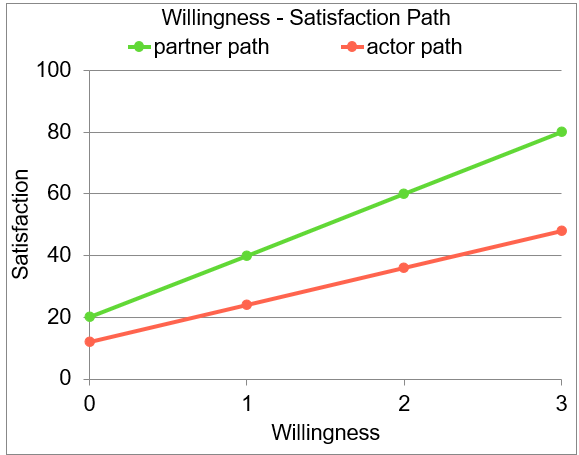

Willingness → Satisfaction Path. Patrick et al. [10] demonstrated that greater perceived need fulfilment is linked to higher partners’ relationship satisfaction. With the same assumption, we can predict that the actor’s willingness to satisfy their partner’s needs is positively correlated with their partner’s relationship satisfaction.

When it comes to the actor path, the situation might be slightly more indirect, since the mechanism behind how one’s willingness affects one’s own satisfaction might be different from how it affects the partner’s satisfaction. Nevertheless, Patrick et al. [10] also demonstrated a positive relation between fulfilling a partner’s needs and higher self-satisfaction, because 1) such fulfilment fosters trust and the partner’s willingness to meet the actor’s needs in return, thus promoting the actor’s satisfaction; and 2) satisfying a partner’s needs also satisfies the actor’s need for relatedness. Therefore, we may also expect that a greater willingness of actors predicts a higher relationship satisfaction for actors themselves, but with a less steep slope.

5. General discussion

Among all the factors that may influence individuals’ satisfaction with intimate relationships, we aim to assess the role of entry motivation. Based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), discrete motivations can be classified and placed on a continuum from the most extrinsic to the most autonomous points [8,9]. We will test how these different motivations affect both individuals’ and their partners’ relationship satisfaction.

In addition, we will examine the mediating effects of the willingness to satisfy one’s partner’s needs on the focal paths. Another important aspect is that the confounding effects of self-esteem, which have not been considered in past work, will be examined in the present study. It has been demonstrated that higher self-evaluations are associated with more autonomous goals at work and with higher relationship satisfaction [13,14], suggesting a plausible correlation between self-esteem and motivation in intimate relationship contexts and a positive link between self-esteem and satisfaction. Consequently, the potentially confounding effects of self-esteem will be controlled to reduce bias. With these considerations, this study design aims to isolate a cleaner path between entering motivation and relationship satisfaction and to elaborate on the underlying mechanisms. By doing this, we make more of the intimacy iceberg visible.

It is expected that more autonomous entry motives may lead to greater dyadic willingness to meet each partner’s needs, which then increases satisfaction for both partners. These anticipated results align closely with and are supported by the findings of Blais et al. [8]. Such results are significant for understanding human intimacy, increasing awareness before relationship decisions, providing empirical evidence to inform premarital counselling, and eventually improving relationship quality.

Admittedly, due to the sample characteristics, the findings may not apply to other age groups, relationships of different durations, or same-sex couples. Additionally, the results may not generalize to Western, individualistic contexts. This is because a collectivistic culture, from a traditional perspective, tends to encourage individuals to obey authorities and sacrifice their personal needs for the group’s broader aims, leading to motivations closer to the extrinsic end. Furthermore, recall bias in reporting entry motives may distort results. Other variables–such as whether couples have children, their financial status, and attachment styles–may also contribute to the variation in relationship satisfaction; nevertheless, they are excluded in the present study to avoid overcomplexity in the models.

Moreover, we did plan to include ISE as covariates for both partners at the initial stage to examine a more holistic self-esteem confounding effect. However, because of the low validity of common ISE measurements [16] and the overcomplexity of the model when combining ISE and ESE, we finally chose to test only the confounding effect of ESE. Nevertheless, this idea can be insightful and may be adopted by future studies with greater resources.

Finally, given the cross-sectional, self-report design, alternative interpretations remain possible: 1) reverse or reciprocal causality (e.g., satisfaction → motivation); and 2) different causal orderings or roles (e.g., motivation functions as a moderator, rather than a mediator, of the willingness → satisfaction link).

To achieve a more comprehensive understanding, further studies could use broader samples, control other variables more strictly, construct more realistic models comprising ISE, adopt longitudinal designs, test these alternative causal paths and roles, and employ better-validated language versions of the scales.

6. Conclusion

As the starting point of intimate relationships, entry motives likely shape how partners interact and feel over time. In this study, we will test whether more autonomous entry motives are associated with greater willingness to meet a partner’s needs and, in turn, higher dyadic satisfaction—even when accounting for self-esteem. If supported, these findings would clarify the direction and magnitude of these associations, deepen understanding of human intimacy in a Chinese context, and inform premarital counselling interventions and decision-making to improve relationship quality and well-being.

References

[1]. Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

[2]. Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

[3]. DePaulo, B. (2017, February 2). What is the divorce rate, really? Psychology Today. https: //www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/living-single/201702/what-is-the-divorce-rate-really

[4]. National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). China Statistical Yearbook 2024. China Statistics Press.

[5]. Hendrick, S. S., Hendrick, C., & Adler, N. L. (1988). Romantic relationships: Love, satisfaction, and staying together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 980–988. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.980

[6]. MacDonald, G., Thapar, S., Ryan, W. S., Chung, J. M., Hoan, E., & Park, Y. (2025). Why do you want a romantic relationship? Individual differences in motives for romantic relationship pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1177/01461672251331699

[7]. Wang, S., Lee, W.-C., & Ma, H. (2024). The Chinese version of the Couples Satisfaction Index: Psychometric assessment and differential item functioning analysis with item response theory. SAGE Open, 14(3), 1–14. https: //doi.org/10.1177/21582440241271087

[8]. Blais, M. R., Sabourin, S., Boucher, C., & Vallerand, R. J. (1990). Toward a motivational model of couple happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1021–1031. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1021

[9]. Knee, C. R., Hadden, B. W., Porter, B., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2013). Self-determination theory and romantic relationship processes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 307–324. https: //doi.org/10.1177/1088868313498000

[10]. Patrick, H., Knee, C. R., Canevello, A., & Lonsbary, C. (2007). The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 434–457. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434

[11]. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https: //doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

[12]. Hadden, B. W., Smith, C. V., & Knee, C. R. (2014). The way I make you feel: How relatedness and compassionate goals promote partner’s relationship satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(2), 155–162. https: //doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.858272

[13]. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257

[14]. Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2014). Development of self-esteem and relationship satisfaction in couples: Two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2291–2303. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0037370

[15]. Bar-Anan, Y., & Nosek, B. A. (2014). A comparative investigation of seven indirect attitude measures. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 668–688. https: //doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0410-6

[16]. Buhrmester, M. D., Blanton, H., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2011). Implicit self-esteem: Nature, measurement, and a new way forward. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 365–385. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0021341

[17]. Hodgins, H. S., Brown, A. B., & Carver, B. (2007). Autonomy and control motivation and self-esteem. Self and Identity, 6(2–3), 189–208. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15298860601118769

[18]. Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of nonindependence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 279–294. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

[19]. Kenny, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (1999). Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships, 6(4), 433–448. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x

[20]. Ledermann, T., & Bodenmann, G. (2006). Moderator- und Mediatoreffekte bei dyadischen Daten: Zwei Erweiterungen des Akteur-Partner-Interdependenz-Modells. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 37(1), 27–40. https: //doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.37.1.27

[21]. Ledermann, T., Macho, S., & Kenny, D. A. (2011). Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor–partner interdependence model. Structural Equation Modeling, 18(4), 595–612. https: //doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.607099

[22]. Moshagen, M., & Bader, M. (2024). semPower: General power analysis for structural equation models. Behavior Research Methods, 56, 2901–2922. https: //doi.org/10.3758/s13428-023-02254-7

[23]. MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https: //doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

[24]. Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2020). Prosocial orientations: Distinguishing compassionate goals from other constructs. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 538165. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.538165

[25]. Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555

[26]. Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

[27]. Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

[28]. Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 623–642. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623

[29]. Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https: //doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Cite this article

Xia,Y. (2025). For Security or for Love? Motives for Entering Romantic Relationships and Dyadic Satisfaction among Chinese Partners. Communications in Humanities Research,98,1-11.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICIHCS 2025 Symposium: Literature as a Reflection and Catalyst of Socio-cultural Change

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

[2]. Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

[3]. DePaulo, B. (2017, February 2). What is the divorce rate, really? Psychology Today. https: //www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/living-single/201702/what-is-the-divorce-rate-really

[4]. National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). China Statistical Yearbook 2024. China Statistics Press.

[5]. Hendrick, S. S., Hendrick, C., & Adler, N. L. (1988). Romantic relationships: Love, satisfaction, and staying together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 980–988. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.980

[6]. MacDonald, G., Thapar, S., Ryan, W. S., Chung, J. M., Hoan, E., & Park, Y. (2025). Why do you want a romantic relationship? Individual differences in motives for romantic relationship pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1177/01461672251331699

[7]. Wang, S., Lee, W.-C., & Ma, H. (2024). The Chinese version of the Couples Satisfaction Index: Psychometric assessment and differential item functioning analysis with item response theory. SAGE Open, 14(3), 1–14. https: //doi.org/10.1177/21582440241271087

[8]. Blais, M. R., Sabourin, S., Boucher, C., & Vallerand, R. J. (1990). Toward a motivational model of couple happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1021–1031. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1021

[9]. Knee, C. R., Hadden, B. W., Porter, B., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2013). Self-determination theory and romantic relationship processes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 307–324. https: //doi.org/10.1177/1088868313498000

[10]. Patrick, H., Knee, C. R., Canevello, A., & Lonsbary, C. (2007). The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 434–457. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434

[11]. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https: //doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

[12]. Hadden, B. W., Smith, C. V., & Knee, C. R. (2014). The way I make you feel: How relatedness and compassionate goals promote partner’s relationship satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(2), 155–162. https: //doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.858272

[13]. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257

[14]. Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2014). Development of self-esteem and relationship satisfaction in couples: Two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2291–2303. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0037370

[15]. Bar-Anan, Y., & Nosek, B. A. (2014). A comparative investigation of seven indirect attitude measures. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 668–688. https: //doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0410-6

[16]. Buhrmester, M. D., Blanton, H., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2011). Implicit self-esteem: Nature, measurement, and a new way forward. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 365–385. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0021341

[17]. Hodgins, H. S., Brown, A. B., & Carver, B. (2007). Autonomy and control motivation and self-esteem. Self and Identity, 6(2–3), 189–208. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15298860601118769

[18]. Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of nonindependence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 279–294. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

[19]. Kenny, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (1999). Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships, 6(4), 433–448. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x

[20]. Ledermann, T., & Bodenmann, G. (2006). Moderator- und Mediatoreffekte bei dyadischen Daten: Zwei Erweiterungen des Akteur-Partner-Interdependenz-Modells. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 37(1), 27–40. https: //doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.37.1.27

[21]. Ledermann, T., Macho, S., & Kenny, D. A. (2011). Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor–partner interdependence model. Structural Equation Modeling, 18(4), 595–612. https: //doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.607099

[22]. Moshagen, M., & Bader, M. (2024). semPower: General power analysis for structural equation models. Behavior Research Methods, 56, 2901–2922. https: //doi.org/10.3758/s13428-023-02254-7

[23]. MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https: //doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

[24]. Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2020). Prosocial orientations: Distinguishing compassionate goals from other constructs. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 538165. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.538165

[25]. Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555

[26]. Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

[27]. Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

[28]. Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 623–642. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623

[29]. Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https: //doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02