1.Introduction

With the popularization of music art and the scientific and systematic development of violin education, the number of modern violin learners has significantly increased, and their performance levels have generally improved. In the advanced stages of violin learning, musicians inevitably come into contact with a plethora of virtuosic compositions. Such pieces serve as a means to fully showcase the performer’s skills and are frequently used in educational, examination, performance, and competition settings. The virtuosic vocabulary in music possesses its unique significance and role, but due to its high level of difficulty, performers often focus their attention on mastering the technical aspects while neglecting its emotional depth.

The emergence of any new form or style of art is inevitably influenced by the era in which it arises. Most scholars have approached their studies from the perspective of analyzing specific technical challenges within particular violin compositions. However, there is still room for research regarding the virtuosity art of the violin itself. Therefore, this thesis primarily investigates the temporal factors contributing to the emergence of violin virtuosity art and its manifestations in application. The theoretical significance of this chosen topic lies in its potential to enrich relevant literature within the fields of music history and the history of instrumental development. In practical terms, this research aligns with the learning patterns and application needs of contemporary violin performers, thereby inspiring performers to contemplate their approach to various virtuosic musical compositions.

2.The Emergence of Violin Virtuosity Art

2.1.Definition of Virtuosity

The term “virtuosity” originally derives from the Italian word “Virtuoso.” In the 16th and 17th centuries, it referred to “a musician who achieved brilliant accomplishments and possessed extraordinary technical skills.” With the flourishing of opera and instrumental concertos in the late 18th century, the term “Virtuoso” began to refer to violinists, pianists, singers, and others who pursued solo careers. It also denoted the acts of performers showcasing exceptional talents [1].

The distinction between virtuosity and non-virtuosity is relative, as music inherently involves varying levels of technical proficiency. Virtuoso techniques refer to exceptionally difficult skills that require extensive time and practice to master. In violin technique, these include double harmonics, octave and tenth shifts, left-hand pizzicato, rapid spiccato bowing, and bow tossing, among others.

2.2.Background for the Formation of Virtuosity Art

2.2.1.Style Inheritance and Technological Advancements

Virtuosity in compositions is specifically demonstrated through the application of techniques that enhance musical decoration, such as tremolo, rapid trills, high notes, improvisational singing or playing, and more. In fact, the practice of “ornamenting” music can be traced back to the Baroque period. Since the 17th century, the constraints of religious influence on composition and tonality gradually loosened, resulting in greater artistic diversity. Initially, virtuosity manifested as vocal techniques in the realm of singing. During the Baroque era, opera began to flourish, and various vocal embellishments, fast melodic lines, ornamental phrases, and improvisational singing techniques from bel canto were incorporated into the compositional thinking of instrumental works. With the violin being an Italian traditional classical and opera accompaniment instrument, coupled with extensive development and the influence of operatic art, musicians began to design more elaborate performances that aligned with the characteristics of the violin.

As composers delved deeper into the study of the violin, solo and concerto compositions for the instrument proliferated. This prompted innovations in violin-making techniques and led to the rise of prominent violin-making families (such as Stradivari and Guarneri). Violins of the 18th century, whether in their construction or tone, closely resemble modern violins, designed in a way that best allows performers to showcase their technical prowess.

During the Baroque era, the violin was primarily used to perform chamber music that featured simple techniques, elegance, and did not demand great volume. However, as violin music flourished, old-style violins and bows could no longer meet the needs of advancing violinists. To increase volume, enrich tone, and provide more expressive possibilities, violin makers made various improvements. This made violin virtuosity possible and created the prerequisites for public concerts in music halls.

Table 1: Comparison between Baroque Violin and Modern Violin.

Feature |

Baroque Violin |

Modern Violin |

Neck |

Short, extending from the body |

Long, with the neck raised above the body |

Fingerboard |

Relatively short, “V”-shaped |

Longer, narrow, and thick |

Tailpiece |

Wide and low |

Arched and high |

Bassbar |

Short and light |

Thick, designed to withstand higher string tension |

Soundpost |

Thin |

Thick |

Bow |

Convex bowstick, shorter bow hair |

Straight or slightly concave bowstick, longer and wider bow hair |

Strings |

Often made of gut strings |

Metal strings |

Sound Quality |

Smaller volume, subdued and soft |

Larger volume, bright and brilliant |

2.2.3.Social Change and Commercial Demand

The emergence of Romanticism as a musical style was influenced by the societal context of the time. The late 18th to early 19th centuries were marked by political upheaval in Europe, with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 and the subsequent restoration of feudal monarchies in 1815, leading to significant societal transformations. However, the bourgeois revolutions were not entirely thoroughgoing: in some countries, the bourgeoisie seized power but could not consolidate it; in others, they compromised with feudalism to form constitutional monarchies; and in some cases, the old systems remained unchanged [2]. In this era, marked by the intertwining of republics and empires, revolution and royalism, reform and restoration, aggressive wars and national spirit, people’s inner lives were filled with contradictions and anxieties, and they harbored desires and concerns about the future and their ideals. Musicians were influenced by these new currents of thought, and it was inevitable that their works would reflect these influences. In terms of form, they broke with tradition, creating composite and flexible genres such as single- or multi-movement programmatic symphonies, symphonic poems, and shorter instrumental preludes, etudes, and fantasies. In terms of content, they placed greater emphasis on expressing intense subjective emotions, showcasing individual styles, using new compositional techniques, and developing new performance techniques. These breakthroughs directly contributed to the birth of virtuoso styles.

Simultaneously, the mechanisms of music performance also reflected the direction of music demand from a particular social class during this unique historical period. Before the 18th century, music performances were limited to relatively private venues such as churches and courts, and the common populace did not have the privilege of enjoying music. In the 19th century, as the bourgeoisie rose in status and aristocratic regimes waned, musical activities gradually reached European urban communities. Market-oriented features of music became increasingly evident, with a thriving music-related industry, including printing, publishing, and sales [3]. Music academies were also established. These developments provided objective conditions for the growth of virtuosity art.

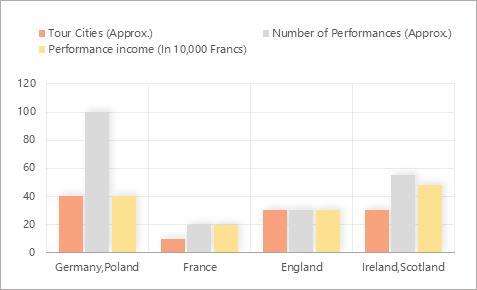

The virtuosity art, which vividly embodies the freedom and passion of Romanticism music, gained popularity among the masses. Musicians who could perform highly challenging pieces became symbols of heroism. Consequently, the profit-oriented “star-making” model demanded even more astonishing techniques and innovations in music composition and performance. Niccolò Paganini stands as a representative “star” performer.

Figure 1: Overview of Paganini’s European Tour [4][5].

3.Characteristics of the Application of Violin Virtuosity Art

3.1.Common Genres of Virtuoso Compositions

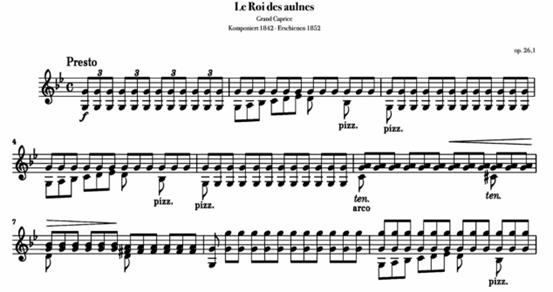

3.1.1.Capriccio

As the name suggests, the term “Capriccio” refers to a musical genre characterized by a certain degree of freedom. It first appeared in the latter half of the 16th century as a type of instrumental composition where different voices imitate each other, exhibiting a fugue-like quality. Structurally, Capriccio compositions possess an element of unpredictability and titling. Starting in the 17th century, Capriccio deepened its connection with composition techniques and aesthetic performance.

During the 18th century, the brilliant sections in concertos or sonatas were often referred to as “Capriccio,” denoting the most ornamental, improvisational, and technically demanding passages within a work. Later on, “Capriccio” began to be widely used in its true sense, serving as practice pieces with a higher degree of difficulty. They were more entertaining than typical practice exercises.

3.1.2.Variations

Variations, or “variation” in music, refer to a series of transformations of a given theme, unified by a consistent artistic concept. The themes of variations are typically short, usually spanning 8-32 measures. When the theme reappears, some elements of the music have changed while preserving certain original elements. The altered theme is referred to as a “variation.” Additionally, “variation” also refers to this compositional technique of maintaining some elements while altering others.

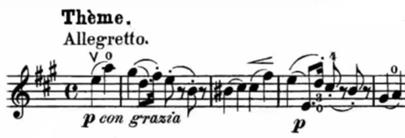

Variations generally involve embellishments over a thematic framework, resulting in ornamentation, freedom, and complexity—reasons why virtuoso vocabulary is often found within them. Different variations often emphasize various virtuoso techniques. For instance, in the second variation of Wieniawski’s “Theme and Variations,” left-hand pizzicato is prominently used.

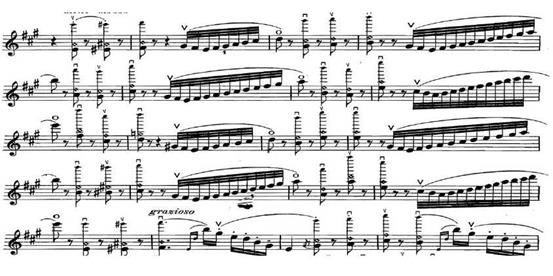

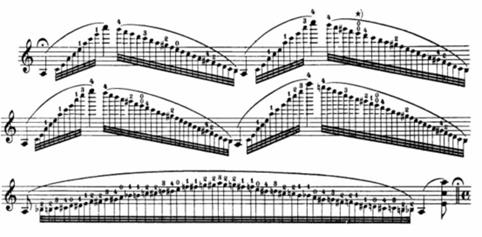

Example 1-1: Excerpt from Wieniawski’s “Theme and Variations” - Theme Fragment.

Example 1-2: Excerpt from Wieniawski’s “Theme and Variations” - Variation II Fragment.

For an extended period in history, variation techniques primarily focused on the complexification of the thematic melody. This approach received criticism from many contemporary critics who argued that an excessive emphasis on decorative melodies would render the music devoid of meaningful content and detract from the original theme’s essence. Later on, composers intentionally reduced repetition, increasingly utilizing character variations and developmental variations. During the Romantic era, “Theme and Variations” found widespread application, with more enriched content.

3.1.3.Concertos

A concerto is a large-scale instrumental suite in which one or more instruments (a small ensemble of instruments) collaborate with an orchestra. It originates from the Latin “Concertare,” meaning “to work together” or “to contend, dispute.” This aptly describes the relationship between the solo instrument and the orchestra—cooperative yet competitive. Concertos are primarily divided into two types: solo concertos and concerto grosso.

Under the influence of Romanticism, concertos became outlets for composers to express their intense personal emotions. To achieve a more powerful expression through the solo instrument, solo concertos began to dominate. Brilliant sections in concertos are typically the most challenging passages. Here, the orchestra stops playing, allowing the soloist to fully showcase the instrument’s capabilities and performance skills. Initially, composers were responsible for marking the locations of these brilliant sections in the score, leaving the soloist to improvise. However, this practice sometimes led to exaggerated and artificial performances, challenging the thematic style of the original work. As a result, composers began to write brilliant sections themselves, clearly notating them to unify thematic ideas with technical execution.

3.2.Application Scenarios of Virtuoso Compositions

3.2.1.Public Concerts

Public concerts are open musical performances held in concert halls, and this mechanism took shape during the late Classical period. Initially, music was primarily created to serve the aristocracy. During that time, musicians had low status and lived in poverty. They had to act as “servants of art,” catering to the preferences of the nobility, which limited the diversity of themes and innovations in instrumental performance techniques.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as the power of feudalism waned in Europe, musicians gradually broke free from the control of the old regime. On one hand, the mechanism of public concerts placed common people and aristocrats on equal footing—if one could afford a ticket, they had the right to enjoy the music performance. On the other hand, the spirit of freedom, equality, and individualism allowed musicians to resist being trapped in the “cage,” producing soulless works. Consequently, many musicians became independent artists or signed performers, cooperating with orchestras, publishers, theater managers, and more. They embarked on international concert tours, and their styles and themes were no longer constrained. Musicians could freely express their individuality and skill, aligning with the contemporary aesthetic interpretation. Virtuoso art was widely applied in concert performances, attracting greater popularity and higher profits.

3.2.2.Salons

If the mechanism of public concerts marked a thorough revolution against the courtly music system, then the salon mechanism can be seen as a “partially preserved revolution.” Salons emerged in the 17th century as a form of aristocratic social gatherings, often accompanied by meetings, refreshments, and dance performances. In the 19th century, the demands of the bourgeoisie prompted a transformation of the salon mechanism. The rising middle class had the resources to pursue musical art and engage in politics. They began to emulate the aristocracy by hosting salons in their homes and inviting upper-class individuals who possessed knowledge, reputation, and influence to participate, thereby elevating their own cultural tastes. Some nobles also began to admit elite figures from the middle class into their salons [6].

Salons were not large in scale, so they primarily featured small-scale musical compositions, such as chamber music, musical miniatures, adaptations of art songs, virtuosic caprices, and variations. The number of performers on stage was usually limited, and the instruments used were mainly stringed instruments and pianos. Salons combined entertainment with functionality, requiring musical pieces to contain both dazzling techniques to please the audience and delicate subtlety that did not overwhelm. This played a pivotal role in the development of violin virtuosity art.

3.3.Writing Characteristics of Virtuoso Vocabulary

By studying examples of virtuoso compositions for the violin from the Romantic period, we can identify several typical characteristics contained within virtuoso vocabulary. Composers often utilize these features to enhance the expressiveness of their music.

3.3.1.Extremely Fast Tempo

The majority of virtuoso vocabulary deviates from the basic tempo. Extremely fast playing speeds make the notes more densely packed and compact, evoking a sense of tension, excitement, and visual stimulation. It is a crucial element in conveying musical flow and propulsion. Some highly skilled violinists, with great confidence, even perform at speeds that exceed the original requirements of the composition.

Example 2: Ernst’s “Fantaisie Brillante” measures 1-9.

3.3.2.Varied Tone Colors

Performers can alter the violin’s tone color by employing different techniques, showcasing various emotional characteristics. This relies on the left-hand fingering and the right-hand bowing control. For instance, the use of harmonics, as shown in Example 3, creates a pure and beautiful atmosphere reminiscent of a waltz style, with accents on the downbeats to give it a jumping quality. Virtuoso vocabulary often includes the extreme application of a specific technique, emphasizing distinct musical characters, or a combination of multiple techniques to enrich the sonic effects, creating a contrasting and layered texture.

Example 3: Wieniawski’s “Faust Fantasy” measures 332-351.

3.3.3.Abrupt Changes in Pitch Range

Virtuoso violin vocabulary often presents melodic progressions that range from extremely low to extremely high pitches or vice versa. This is expressed through continuous scales, arpeggios, large leaps, or string crossings, reminiscent of the “coloratura” in opera. These changes in pitch range shift the atmosphere between profundity and brightness, providing sensory stimulation through dramatic melodic development.

Example 4: Paganini’s “Caprice No. 5” excerpt.

3.3.4.Abundance of Double Stops and Chords

The violin, primarily a single-voice instrument, often plays single-voice melodies. The use of double stops and chords can convey a sense of voice layering and harmonic variation. This includes parallel or contrary motion between different voices, cross-pollination between major and minor keys, among other techniques. These methods enrich the melody, creating a sense of contrast or ambiguity that is characteristic of the Romantic era.

Example 5: Wieniawski’s “Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp Minor” first movement measures 169-174.

4.The Role of Violin Virtuosity

4.1.Developing Physical Abilities

Virtuosity is a way for musicians to showcase greater physical possibilities to their audiences. It is often said that the hands of violin virtuosos are like those of magicians. In reality, from a kinesiological perspective, the fundamental principles behind these high-level techniques can be summarized as rapid finger position changes, extensive finger stretching, continuous use of multiple fingers, coordination between the left and right hands, muscle control, and more. As long as there are no congenital limitations, ordinary learners can achieve these skills through continuous practice. The level of teaching, the learner’s stage and aptitude, practice methods, and the learner’s physical condition can all have an impact. The process of achieving these skills is essentially a process of enhancing physical capabilities.

For example, when a learner practices the sixth variation of Paganini’s “24th Caprice,” they may find it challenging to execute the rapid octave and tenth finger position changes, accompanied by a strong sensation of finger tension and discomfort. This reflects insufficient finger stretching capability. Learners, based on a solid foundation of basic skills, can gradually improve finger flexibility through prolonged, slow-paced practice, learning relaxation techniques, muscle coordination, and incorporating supplementary exercises. Over time, their stretching capabilities will improve, making it easier to perform various pieces of music.

4.2.Fostering Musical Emotions

Technique serves as a means to express music, and any emotional expression is built upon a certain level of technique. Even when a violinist plays a simple piece of music, they use smooth bowing, appropriate bow-string contact points, variations in bow speed and pressure, and expressive string manipulation to convey its beauty to the audience. Basic techniques play a significant role in this process, but virtuosic passages excel in showcasing emotional characteristics in various musical elements such as rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, and dynamics. For instance, fast rhythms can represent passion, tension, or anger, major keys can convey brightness and beauty, and dissonant chords can reflect inner conflict. Therefore, many composers use rapid and nimble finger movements to drive emotions to climaxes, employ harmonic colors to express inner serenity and purity, and use techniques like pizzicato and spiccato to create lively and exuberant characterizations.

However, the evaluation of virtuosic styles by music critics is mixed. In issue 35 of the “Theater Newspaper” by Viennese critic August Schmidt, there is a comment that reads, “For Paganini, melody is merely a tool, and the emotions he brings are immediately shattered by his sharp bowing technique and completely unrelated, dissolute destruction... Paganini, unlike a great composer, did not create sublime and gentle works but instead thoroughly showcased his own traits.” [7]

Where does the value of virtuosity lie? From the perspective of music aesthetics, the value of music, in general, can be divided into formal beauty and content beauty. Firstly, the formal beauty of virtuosic artistry primarily lies in its decorative nature. Whether in traditional Chinese folk music, Western ornamental variations, or even modern jazz, numerous examples can be seen where the addition of “ornaments” enhances the technical aspects of performance and singing. These agile and intricate phrases undoubtedly add charm and research value to the music, forming a unique style.

Secondly, virtuosity also contains “content beauty.” It is essential to not isolate virtuosic vocabulary from a piece but rather analyze it within the context of the composition. On one hand, virtuosic vocabulary helps composers convey emotions and provide listeners with more intense sensory experiences. For instance, in a Western opera, when a dying protagonist sings an aria, they may unleash a powerful high note (such as High C) at the climax, providing a tremendous emotional impact when combined with the scene. This illustrates the charm and necessity of virtuosic techniques. Romantic-era virtuosity differs from the purely ornamental virtuosity in Baroque operas; it does not focus the audience’s attention entirely on specific decorations or technical means. Instead, it employs virtuosity as one of the effective means to captivate the audience and chooses different techniques for conveying information in various plots and emotions.[8] Additionally, this “content beauty” can also be seen as a form of “human beauty.” The performer’s display of exceptional technical skills precisely showcases human qualities and limitless possibilities: agility, dexterity, intelligence, mastery, and more. From a macro perspective, this epitomizes the spirit of the Romantic era. As the Vienna Theater Newspaper’s review suggests, Paganini displayed his distinctive qualities, but expressing individuality and freedom is the essence of Romanticism. From this perspective alone, Paganini’s artistic creation exemplifies the thoughts of his era.

Hence, performers must pay attention to their musical interpretation of virtuosic passages. When playing challenging segments, they should not focus solely on technical proficiency. They should also emphasize musical elements like melody, harmony, dynamics, and bring out the most crucial aspects. By combining score information and the composition’s background, they can unearth the meaning of virtuosic passages and ensure that the audience’s attention goes beyond the surface of the music, achieving the effect of conveying emotions through technique.

5.Conclusion

To truly understand the meaning of a technique or style, it must be examined within its specific historical context. This paper, using the method of literary research, has explored the emergence and application of virtuosic violin artistry during the Romantic era from the perspectives of history and aesthetics. From this analysis, we can conclude that virtuosity is not only a technical activity in the realm of music but also a means of expression that can be integrated with the content and ideologies of the era. It allows violin musical works to emit a unique charm. Therefore, performers should not focus solely on technical prowess but also recognize the importance of infusing artistic emotions into the music itself. The main purpose of this paper is to summarize and synthesize, leaving room for further case studies in specific examples. To address the limitations of this research, future studies could select representative virtuosic techniques and analyze their role in driving musical emotions through case studies.

References

[1]. Sadie, S. (2001). Virtuoso. In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (7th ed., Macmillan press). London.

[2]. Han, L. (2004). A History of European String Artistry. Beijing: Central Conservatory of Music Press. (pp. 101-102).

[3]. Jia, Y. (2020). The Technical Presentation and Insights into the Artistry of Violin Virtuosity during the Romantic Period. Chengdu Normal College Journal, 36(09), 118-124.

[4]. Wang, J. (2017). An Analysis of Violin Virtuosity during the Western Romantic Period (Doctoral dissertation). Hunan Normal University.

[5]. Luo, Q. (2004). A Comprehensive Overview of Violin Artistry. Shanghai: Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press. (pp. 151-154).

[6]. Jiang, X. (2012). Genius, Timing, and Innate Talent (Master’s thesis). Central Conservatory of Music.

[7]. Fuld, W. (2005). Paganini - The Curse of Talent (L. Xinghua, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai Far East Publishing House. (pp. 127-129).

[8]. Gao, W. (1988). The Aesthetic of Musical Virtuosity. People’s Music, 1988(08), 24-26+36.

Cite this article

Yang,Q. (2023). The Emergence and Application of Violin Virtuosity During the Romantic Period. Communications in Humanities Research,14,70-79.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sadie, S. (2001). Virtuoso. In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (7th ed., Macmillan press). London.

[2]. Han, L. (2004). A History of European String Artistry. Beijing: Central Conservatory of Music Press. (pp. 101-102).

[3]. Jia, Y. (2020). The Technical Presentation and Insights into the Artistry of Violin Virtuosity during the Romantic Period. Chengdu Normal College Journal, 36(09), 118-124.

[4]. Wang, J. (2017). An Analysis of Violin Virtuosity during the Western Romantic Period (Doctoral dissertation). Hunan Normal University.

[5]. Luo, Q. (2004). A Comprehensive Overview of Violin Artistry. Shanghai: Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press. (pp. 151-154).

[6]. Jiang, X. (2012). Genius, Timing, and Innate Talent (Master’s thesis). Central Conservatory of Music.

[7]. Fuld, W. (2005). Paganini - The Curse of Talent (L. Xinghua, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai Far East Publishing House. (pp. 127-129).

[8]. Gao, W. (1988). The Aesthetic of Musical Virtuosity. People’s Music, 1988(08), 24-26+36.