1. Introduction

In the United States, college education has long been considered a key mechanism for upward social mobility across all aspects of our daily life, such as social networks, job opportunities, and even future success. Nevertheless, with the rapid development of technology and society, there are invisible, uncontrollable forces that negatively contribute to the fact of educational inequality, especially to college admissions, while people reinforce and reproduce it. Factors like family background with relatively less resources seem to significantly predict children’s future outcome [1], causing severe disadvantages that are difficult to overcome by mere self-effort, since collective problems require collective actions. Obviously, socioeconomic status has become a non-negligible issue when it comes to the discussion about educational equity.

Additionally, individuals from low socioeconomic status are confronting financial and structural barriers with lacking access to social and human capital, which disproportionately affect their academic performance prior to college by disconnecting them with academic support, thereby further creating the situation of underrepresentation of working class children to apply for higher education due to the class gap. Otherwise, students from wealthy families are more likely to receive and participate in private tutoring, teamwork, and various organized extracurricular activities that facilitate educational attainment and competitive skills for elite colleges [2].

Hence, to identify the “peacebreaker”, who is responsible for bearing the blame of widening social disparity, there is an increasing number of researchers raising concerns to deeply analyze the problem through mediating and moderating variables that can help explain the strength and direction within the causal relationship [3]. Since socioeconomic gap acts on different system levels and interacting environments around an individual, it requires a collective understanding about behaviors, policies, and events taking place within the larger social ecology. Thus, based on their studies, our research draws attention to:

1.In what ways does contemporary educational research on college admissions and American students engage with discussions of socioeconomic inequalities?

2.To what level do researchers apply their understanding of how socioeconomic factors are presented?

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Ecological systems

Our analysis draws on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [4] to examine how contemporary educational research engages with discussions of socioeconomic inequalities in college admissions. From this theoretical grounding, we understand college access as a situated phenomenon, shaped by multiple interacting environmental systems that influence students’ educational trajectories. Socioeconomic disparities in admissions outcomes emerged from reciprocal relationships between the individual students, their immediate situation, and larger institutional structures. Our review aims to identify patterns in how different layers of this educational ecology are examined in existing research.

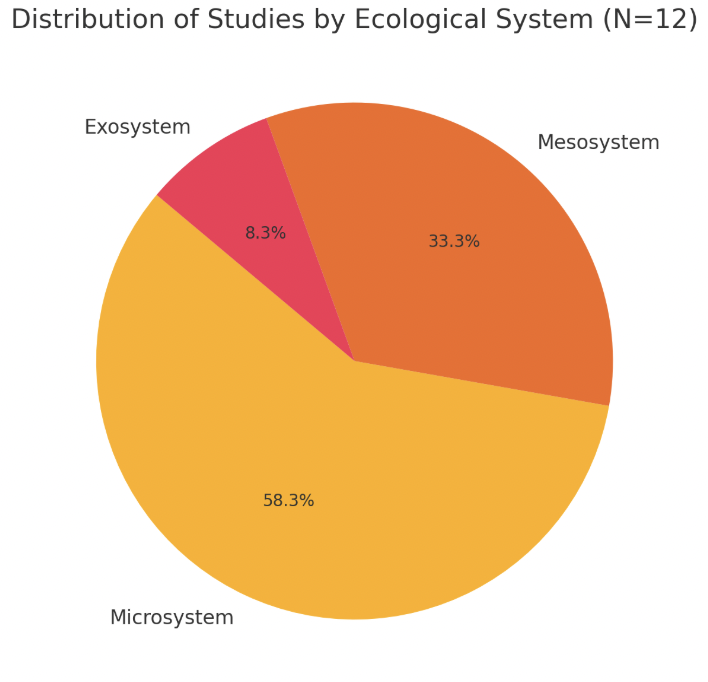

Following Brofenbrenner’s model, an individual’s development is affected by a series of interconnected environmental systems. In the context of college admissions, these systems structure educational opportunities at multiple levels, as shown in Table 1.

|

Type of system |

Definition |

Example case |

Distribution of articles |

|

Microsystem |

The direct environments that shape a student's college access include family, school, peer networks, and counselors. |

Wealthier students receive more parental guidance, attend better-resourced schools, and have stronger college counseling programs, while low-income students may lack these supports (Berkowitz et al., 2017; Hoff, 2013). |

58.3% of articles |

|

Mesosystem |

The connections between different microsystems, such as how family involvement interacts with school counseling or how high school preparation affects financial aid awareness. |

Students from low-income families often attend underfunded schools with limited college advising, making them less informed about financial aid and application strategies (Bottia et al., 2022; Davis, 2021). |

33.3% of articles |

|

Exosystem |

Broader systemic conditions that indirectly influence students, such as financial aid policies, standardized testing requirements, and public university funding. |

The structure of standardized testing policies disproportionately advantages high-income students, as they have greater access to test prep resources and multiple retake opportunities. In contrast, lower-income students face barriers such as limited test prep, school funding disparities, and the high costs of taking standardized exams (Kozlowski, 2020; Bottia et al., 2022). |

8.3% of articles |

|

Macrosystem |

The overarching values and ideologies shaping higher education opportunities include meritocracy beliefs, institutional prestige, and legacy admissions. |

Social class expectations influence who is seen as a ‘good fit’ for elite universities, reinforcing systemic inequalities. Legacy admissions and institutional prestige disproportionately favor students from high-income families (Rubin et al., 2014; Vandelannote, 2024). |

0% of articles |

|

Chronosystem |

The dimension of time captures how educational policies and socioeconomic conditions evolve across generations. |

Shifts in test-optional policies, affirmative action bans, and student loan reforms impact college access for low-income students over time (Bottia et al., 2022; Davis, 2021). |

0% of articles |

At the Microsystem Level, an individual’s family, school, and peer networks play a role in their preparation, confidence, and access to resources. For instance, high-income families often provide paid tutoring, test preparations, and private counseling, while low-income students may lack these supports and rely on underfunded public school resources, which directly affect their preparation and access to college admissions [5,6]. Students who are attending elite high schools may also benefit from better access to college counselling and guidance when compared to their lower-resourced counterparts.

The Mesosystem captures the correlations across the different microsystems. Such examples include how the involvement of parents connects with school counseling resources and financial aid. Parents who are from middle and upper-class families are found to be more likely to engage with their children’s school and academic life, such as securing opportunities like extracurriculars, college visits, or internships [2]. Schools that are well-funded are also more likely to help students with their admissions process. However, underfunded schools lack the resources necessary for individualized support for their student body, therefore, the students get fewer opportunities.

At the exosystem level, the exosystem looks into the more general systemic factors that influence the student’s opportunities but are outside of their direct control. Financial aid programs, state and federal education policies are a few examples [7]. While standardized testing requirements put lower-income students at a disadvantage because they do not have access to test preparation, legacy admissions disproportionately favor wealthy applicants, maintaining class stratification within the more elite institutions.

The Macrosystem level is mainly about how cultural values, social class, and existing institutional norms shape access to higher education. Societal expectations indeed influence who is preferred as a ‘good fit’ for elite universities, reinforcing systemic inequalities to a larger extent. This point can be presented by the prevalent legacy admissions and institutional prestige, which disproportionately favor students from high-income families to carry on the heritage from their family [8]. The common perception of meritocracy in college admissions frequently neglects the obstacles encountered by the lower-income students, therefore perpetuating systemic disparities [9,10].

And last but not least, the Chronosystem recognizes that educational policies and socio-economic factors change over time, affecting college accessibility across different generations. Some examples of this include the recent movement toward test-optional admissions due to the pandemic and the controversies surrounding the debates of affirmative action [11]. Both of these examples show how policies change in response to demands for equity.

By looking at how each level of influence is represented in the studies, our objective is to emphasize the complex and cumulative nature of socioeconomic inequalities in college access, illustrating how the inequalities are influenced by factors that are interconnected through individual, institutional, and systemic levels.

2.2. Limitations and adaptations

While Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a valuable structure for analyzing socioeconomic and educational disparities, our application of the model requires further adaptations. Since the original framework was primarily developed to understand the comprehensive environment around individual development in different psychological and cultural contexts, it does not inherently account for systemic inequalities, such as structural racism, class stratification, or historical marginalization. In order to better address these broader problems, our review modifies the ecological model as a flexible scaffold with a stronger connection to our designed topic, adapting its layers to examine how socioeconomic status operates not only through personal and immediate environments, but also through larger institutional and structural forces. Thus, these adaptations allow us to critically explore the causal mechanism of how educational inequality is perpetuated within and across various system levels.

3. Methods

3.1. Literature search

We carried out a thorough literature search using the EBSCO database, mainly utilizing materials from the University of Washington. For our systematic review, we followed a strict strategic method, merging specific chosen keywords and subject headings relevant to our research focus. To guarantee extensive coverage, we implemented Boolean operators, employing “OR” to link related keywords and “AND” to integrate different subject categories. We limited our search to peer-reviewed articles published prior to 2010, ensuring a relevant time frame of 15 years. This approach resulted in 329 relevant studies, all of which were imported into Covidence for further screening and review processing (see Table 2).

|

Search Term Category (Joined with AND) |

Search Terms in Abstract (Joined with OR) |

|

Socio-economic status |

Socio-economic background, Economic standing, Social standing*, Socioeconomic position*, Social rank*, Economic class*, Socioeconomic level*, Financial status, Social hierarchy, Economic background, Class status, Socioeconomic background, Economic condition*, Social level*, Social position*, Wealth status, Social class*, Economic strat, Socioeconomic factor* |

|

Education inequality |

Education justice, Education accessibility, Education unfairness, Education attainment*, Education gap*, Educational disparity, Unequal access to education*, Education gap*, Learning inequality, Educational inequity, Achievement gap*, Disparities in education*, Educational divide, Inequitable education, School inequality, Disproportionate access to education, Educational disadvantage*, Unequal educational opportunity*, Learning gap*, Academic inequality, Education disparity, Educational opportunity*, Educational policy*, Educational resource*, Learning environment |

3.2. Literature screening

During the screening phase, Covidence automatically identifies and removes any duplicate entries. Four papers were found to be duplicated. The remaining studies were then screened by two independent students, who reviewed titles and abstracts based on our predefined exclusion criteria:

Geographic Mismatch: Only studies conducted within the United States and focused on the U.S. college system were considered; those outside this scope were removed.

-Language Barrier: Only studies written in English were included

-Topic Relevance: Any topic not focusing on the relationship between college admissions and socioeconomic inequalities in the United States will not be included.

-Studies must discuss how contemporary educational research engages with socioeconomic disparities in college access, admission policies, or enrollment rates.

3.3. Literature analysis

After completing the screening process, we proceeded with data extraction and analysis, systematically coding the studies to explore how contemporary educational research engages with socioeconomic disparities in U.S. college admissions. According to the PRISMA diagram of our identification process in Figure 1, our first step was to determine whether each study explicitly examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and college admissions policies.

4. Findings

Across all the studies reviewed, as Figure 2 shows, we have found several patterns when we mapped our research onto Brofenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. The majority of the studies concentrate on the microsystem and the mesosystem levels. More specifically, out of the 12 articles we reviewed, 7 fit into the Microsystem level, 4 fit into the Mesosystem level, leaving only one that fits into the Exosystem level. On the Microsystem level, the findings highlight that socioeconomic status affects students’ emotional resources, early language development, and internal motivation factors that influence their academic readiness from a young age [6,12,13].

As for the mesosystem level, the importance of the connection between key environments such as family-school engagement and school climate was shown, demonstrating that even when students possess strong individual traits, these can either be supported or undermined depending on the quality of interaction between their contexts [5,10]. In contrast, there is a notable gap in research when it comes to the exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. This absence shows a broader trend in the literature: a prioritization of short-term individual-level explanations over structural or long-term analysis. As a result of this, important systemic influences like educational policy and cultural narratives about meritocracy are often overlooked [9,14]. This leaves critical gaps in understanding how inequality is reproduced and sustained across generations.

Beyond the ecological placement, other thematic findings have surfaced as well. Across the studies, we can see a clear pattern emerge: lower SES students face structural disadvantages not only due to fewer material resources but also because of cultural mismatches between their home environments and institutional expectations [15]. For instance, some studies find that students from working-class backgrounds struggle with hidden norms around self-advocacy or help-seeking, which educators can misread as disinterest [9,13]. And plus, when families are less visible in school spaces, this can often be interpreted as a lack of investment, despite strong educational values in the home [16].

What is also worth noticing is that multiple studies suggested that psychological and subjective factors such as perceived social class, career adaptability, and levels of hope can mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic success [9,12,17]. Students' self-perceptions often predict their aspirations and outcomes more accurately than objective measures like parental education or income. In this way, subjective social class emerges as a meaningful construct in admissions research.

While school climate isn’t our main focus, it did emerge as a key factor in several studies. Supportive, inclusive education environments can buffer the negative effects of low socio-ecionmic status, allowing the students with disadvantaged backgrounds to thrive academically [5,18].

5. Conclusion

5.1. Summary

Our findings present significant explanations about the mechanism of how socioeconomic gaps are affecting students’ academic performance and achievement through different dimensions. Most of the literature on college admissions disparities focuses on socioeconomic factors, but how these factors are examined varies significantly across moderating variables. Some studies emphasize individual and family-level influences in the microsystem, while others focus on institutional barriers and policies in the exosystem, yet these perspectives are rarely integrated. Amazingly, there is limited research addressing the level of macrosystem, which is strongly related to governmental policy-design toward different socioeconomic groups. Additionally, socioeconomic status is often analyzed in isolation, overlooking intersections with race, gender, and geographic location. Research tends to prioritize immediate and short-term disparities like personal hope to get better [12] rather than long-term systemic changes in the chronosystem, leaving gaps in understanding how policies evolve.

It is necessary for future studies to pay more attention to contributors in the macro and chrono level that can well predict the persistence and reproduction of socioeconomic inequalities in college admissions. Even though much research has indeed discussed the factors at the individual and family level, broader systemic issues still remain underexplored. The macro level, which encompasses institutional policies, economic systems, and even cultural ideologies, also plays an important role in shaping the educational trajectory, clarifying the fact of inequality that is arbitrarily being perpetuated or reinforced over time.

5.2. Policy implications and future directions

To address these persistent disparities, future research should also take actionable reforms under the condition that we lack governmental forces. At the level of microsystems, increasing investment in school counselors, who are able to directly talk to students with appropriate support, strengthens students’ self-confidence and inner cognitive development, especially in urban schools that contain disadvantaged populations [19]. Then, mentorship programs accompanied by peer-based support networks are also helpful to empower students from marginalized backgrounds. Meanwhile, the mesosystem requires relationship building, in which parents should be involved to interact with the schools through activities like parent-teacher meetings in order to encourage their children with college planning and technical support [20].

In terms of the exosystem with indirect forces, we need reevaluations and transformations in standardized testing and financial aid systems in the aspect of equal opportunity. Unfortunately, research indicates that merely 0.6% of students from poor-resourced schools score 1300 or above on the SAT, whereas 33% of students from the highest income households can achieve this score [7]. Due to the accessibility to academic resources, college admissions should consider making standardized exams like SAT optional, while paying more attention to extracurriculars, GPA, and essays for the sake of capturing a whole picture of every single individual beyond simply testing score. Additionally, the local government should make it easier for eligible students to access and complete the Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) application, which should be designed to always keep a certain percent of financial aid for them, increasing the number of students from disadvantaged families to actually receive assistance.

For the macrosystem level, dominant cultural values, institutional norms, and even larger ideologies are all related to meritocracy and the following legacy admissions, disproportionately favoring individuals with privileged backgrounds, like wealth and elite social networks [8]. It is necessary to eliminate this legacy preference that prioritizes certain families, and instead adopt holistic admission systems with more inclusive measurements. Finally, at the level of the chronosystem, researchers and educators should monitor and evaluate how educational policies evolve in the long run based on longitudinal data collection and, then, provide appropriate advice and intervention on time to improve college admission for students in need. In the nutshell, by integrating these structural solutions, researchers can shift from merely papering inequality to actively practicing policy changes that promote educational justice.

References

[1]. Rumberger, R. W. (2010). Education and the reproduction of economic inequality in the United States: An empirical investigation. Economics of Education Review, 29, 246–254.

[2]. Snellman, K. , Silva, J. M. , Frederick, C. B. , & Putnam, R. D. (2014). The engagement gap. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 194–207. https: //doi. org/10. 1177/0002716214548398

[3]. Moskowitz, S. D. (1942). Socio-economic factors as predictors of academic achievement: A study of the relationship between the socio-economic background and the academic achievement of the 6S classes of selected schools in districts 45 and 66, Queens County, New York City [Doctoral dissertation, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor].

[4]. Simply Psychology. (2024). Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory. https: //www. simplypsychology. org/bronfenbrenner. html

[5]. Bekerman, R. , Madjar, H. , & Amir, R. A. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469. https: //doi. org/10. 3102/0034654316669821

[6]. Hoff, E. (2013). Interpreting the early language trajectories of children from low-SES and language minority homes: Implications for closing achievement gaps. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 4–14.

[7]. Georgetown University. (2023). SAT score gaps reveal deeper inequality in education, opportunity. The Feed. https: //feed. georgetown. edu/access-affordability/sat-score-gaps-show-the-consequences-of-widening-economic-disparities/

[8]. Honor Society Foundation. (n. d. ). Legacy Admissions: Upholding Privilege or Meritocracy? Retrieved from https: //honorsocietyfoundation. org/legacy-admissions-upholding-privilege-or-meritocracy/

[9]. Rubin, M. , Denson, N. , Kilpatrick, S. , Matthews, K. E. , Stehlik, T. , & Zyngier, D. (2014). "I am working-class": Subjective self-definition as a missing measure of social class and socioeconomic status in higher education research. Educational Researcher, 43(4), 196–200.

[10]. Vandelannote, I. , & Demanet, J. (2024). One way or another: An optimal matching analysis of students' educational pathways and the impact of socioeconomic background and engagement. British Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 416–443. https: //doi. org/10. 1002/berj. 4077

[11]. Masjutina, S. , & Stearns, E. (2025). A qualitative investigation of the influences of gender among low-socioeconomic status students’ motivations to study biology. International Journal of STEM Education, 12(7).

[12]. Dixson, D. D. , Keltner, D. , Worrell, F. C. , & Mello, Z. (2018). The role of hope in predicting school engagement among African American and Latino adolescents. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 507–515. https: //doi. org/10. 1080/00220671. 2017. 1302915

[13]. Kornfeld, K. P. (2020). Socioeconomic inequality in decoding instructions and demonstrating knowledge. Qualitative Sociology, 43, 43–66. https: //doi. org/10. 1007/s11133-019-09442-y

[14]. Cowan, M. C. , James, C. , Shappell, E. , & Mickle, R. A. (2022). Socioeconomic differences in North Carolina college students’ pathways into STEM. Teachers College Record, 124(1), 30–61. https: //journals. sagepub. com/home/tcz

[15]. Goudeau, S. , Soria, N. M. , Monceau, H. R. , Darnon, C. , Croizet, J. -C. , & Cimpian, A. (2024). What causes social class disparities in education? The role of the mismatches between academic contexts and working-class socialization contexts. Psychological Review. https: //doi. org/10. 1037/rev0000473

[16]. Bibha, R. N. , & Parul, D. (2019). Role of socio-economic conditions on students’ education. The Clarion, 8(2), 56–61.

[17]. Eshelman, A. (2013). Socioeconomic status and social class as predictors of career adaptability and educational aspirations in high school students [Master’s thesis, Southern Illinois University Carbondale].

[18]. Denson, L. (2021). Poverty and middle level achievement in a Common Core state: What are we missing? Calls for Change in Middle Grades Education, 7(3), Article 6.

[19]. MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership. (2021). Mentoring and Educational Outcomes. Retrieved from https: //www. mentoring. org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Mentoring-and-Educational-Outcomes. pdf

[20]. National Association of Secondary School Principals. (n. d. ). Poverty and Its Impact on Students' Education. Retrieved from https: //www. nassp. org/poverty-and-its-impact-on-students-education/

Cite this article

Zhang,J.;Fortner,M.;Li,Y.;Chi,Y.;Wan,H. (2025). The Uncrossable Gap? Education Achievement and Social Mobility. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,100,35-44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Understanding Religious Identity in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rumberger, R. W. (2010). Education and the reproduction of economic inequality in the United States: An empirical investigation. Economics of Education Review, 29, 246–254.

[2]. Snellman, K. , Silva, J. M. , Frederick, C. B. , & Putnam, R. D. (2014). The engagement gap. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 194–207. https: //doi. org/10. 1177/0002716214548398

[3]. Moskowitz, S. D. (1942). Socio-economic factors as predictors of academic achievement: A study of the relationship between the socio-economic background and the academic achievement of the 6S classes of selected schools in districts 45 and 66, Queens County, New York City [Doctoral dissertation, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor].

[4]. Simply Psychology. (2024). Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory. https: //www. simplypsychology. org/bronfenbrenner. html

[5]. Bekerman, R. , Madjar, H. , & Amir, R. A. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469. https: //doi. org/10. 3102/0034654316669821

[6]. Hoff, E. (2013). Interpreting the early language trajectories of children from low-SES and language minority homes: Implications for closing achievement gaps. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 4–14.

[7]. Georgetown University. (2023). SAT score gaps reveal deeper inequality in education, opportunity. The Feed. https: //feed. georgetown. edu/access-affordability/sat-score-gaps-show-the-consequences-of-widening-economic-disparities/

[8]. Honor Society Foundation. (n. d. ). Legacy Admissions: Upholding Privilege or Meritocracy? Retrieved from https: //honorsocietyfoundation. org/legacy-admissions-upholding-privilege-or-meritocracy/

[9]. Rubin, M. , Denson, N. , Kilpatrick, S. , Matthews, K. E. , Stehlik, T. , & Zyngier, D. (2014). "I am working-class": Subjective self-definition as a missing measure of social class and socioeconomic status in higher education research. Educational Researcher, 43(4), 196–200.

[10]. Vandelannote, I. , & Demanet, J. (2024). One way or another: An optimal matching analysis of students' educational pathways and the impact of socioeconomic background and engagement. British Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 416–443. https: //doi. org/10. 1002/berj. 4077

[11]. Masjutina, S. , & Stearns, E. (2025). A qualitative investigation of the influences of gender among low-socioeconomic status students’ motivations to study biology. International Journal of STEM Education, 12(7).

[12]. Dixson, D. D. , Keltner, D. , Worrell, F. C. , & Mello, Z. (2018). The role of hope in predicting school engagement among African American and Latino adolescents. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 507–515. https: //doi. org/10. 1080/00220671. 2017. 1302915

[13]. Kornfeld, K. P. (2020). Socioeconomic inequality in decoding instructions and demonstrating knowledge. Qualitative Sociology, 43, 43–66. https: //doi. org/10. 1007/s11133-019-09442-y

[14]. Cowan, M. C. , James, C. , Shappell, E. , & Mickle, R. A. (2022). Socioeconomic differences in North Carolina college students’ pathways into STEM. Teachers College Record, 124(1), 30–61. https: //journals. sagepub. com/home/tcz

[15]. Goudeau, S. , Soria, N. M. , Monceau, H. R. , Darnon, C. , Croizet, J. -C. , & Cimpian, A. (2024). What causes social class disparities in education? The role of the mismatches between academic contexts and working-class socialization contexts. Psychological Review. https: //doi. org/10. 1037/rev0000473

[16]. Bibha, R. N. , & Parul, D. (2019). Role of socio-economic conditions on students’ education. The Clarion, 8(2), 56–61.

[17]. Eshelman, A. (2013). Socioeconomic status and social class as predictors of career adaptability and educational aspirations in high school students [Master’s thesis, Southern Illinois University Carbondale].

[18]. Denson, L. (2021). Poverty and middle level achievement in a Common Core state: What are we missing? Calls for Change in Middle Grades Education, 7(3), Article 6.

[19]. MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership. (2021). Mentoring and Educational Outcomes. Retrieved from https: //www. mentoring. org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Mentoring-and-Educational-Outcomes. pdf

[20]. National Association of Secondary School Principals. (n. d. ). Poverty and Its Impact on Students' Education. Retrieved from https: //www. nassp. org/poverty-and-its-impact-on-students-education/