1. Introduction

Macrolides rank among the world's most frequently prescribed antibiotics, employed for the treatment of a broad spectrum of infections mostly caused by Gram-positive bacteria but also Gram-negative bacteria to a lesser extent [1]. In 1950, the pioneering macrolide antibiotic, pikromycin, aptly named for its distinctive bitter flavor, was extracted from a strain of Streptomyces. [2]. At present, macrolides are utilized in the treatment of chronic lung inflammatory conditions. Among the conditions encompassed are diffuse panbronchiolitis, cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma[3-5]. Recent studies reveal that erythromycin exerts dual effects on the translation process: it halts the elongation of polypeptide chains and concurrently impedes the assembly of the large ribosomal subunit[6]. Nevertheless, the development of resistance to antimicrobials among bacteria that frequently cause community-acquired respiratory tract infections (CA-RTIs) is increasingly posing a significant challenge in clinical practice. There is a rising incidence of multidrug resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, including diverse macrolide resistance profiles, observed in isolates obtained from CA-RTIs[7]. Moreover, a trend of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in pediatric populations can be observed[8]. Additionally, in mainland China, macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis (MRBP) has been on the rise and has become prevalent, attributed to the emergence of macrolide-resistant mutations since 2011[9]. There is a pressing requirement to discover new antibiotics to alleviate the current situation, and there are two possible ways, modification of existing drugs and finding of new drugs.

2. The structure of macrolides

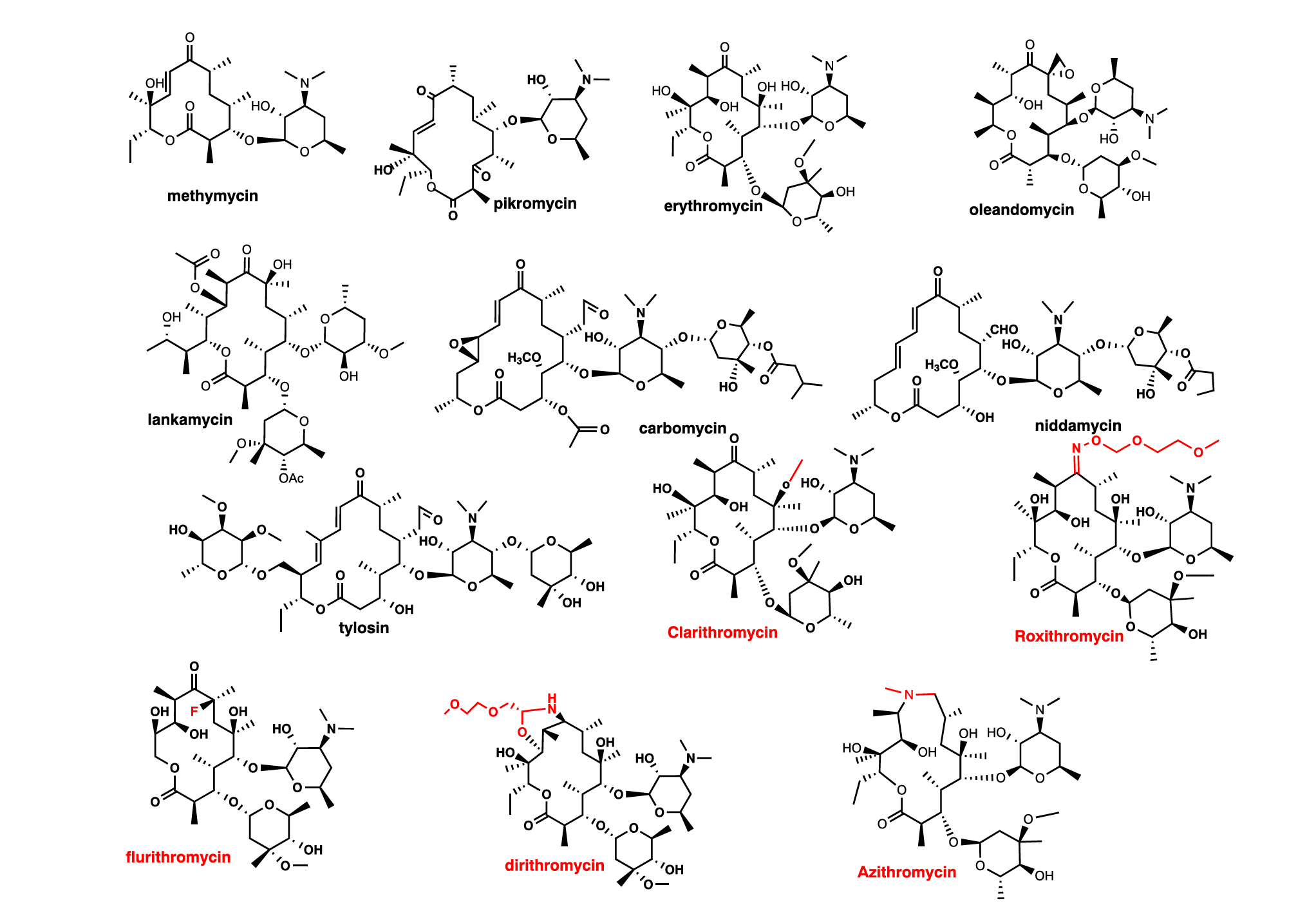

Macrolide antibiotics are categorized by the composition of their macrocyclic lactone rings, which consist of 14, 15, or 16 atoms (Fig.1). Most macrolide antibiotics feature amino sugar and/or neutral sugar components that are attached to the lactone ring through a glycosidic linkage. The initial class of macrolide antibiotics, known as the first generation, was sourced entirely from natural products[10]. The first generation of macrolide antibiotics includes various natural products, among which are 12-membered methymycin, 14-membered pikromycin, erythromycin, oleandomycin, and lankamycin, as well as 16-membered carbomycin, niddamycin, and tylosin. These compounds are naturally derived, typically synthesized by actinomycetes. In the figure, the red coloration indicates the modifications that have been applied to the erythromycin molecule, creating the second generation of macrolides, which feature macrocyclic lactone rings consisting of either 14 or 15 atoms (Fig.1). The second generation of macrolide antibiotics mainly includes 14-membered compounds such as clarithromycin, roxithromycin, flurithromycin, and dirithromycin, along with the distinctive 15-membered azithromycin. Understanding the structure of macrolides can help create more new drugs.

Figure 1. The first generation and the second generation of macrolides (adapted[11])

3. The mode of action

Macrolides can inhibit the synthesis of proteins in bacteria by specifically targeting the ribosome. They bind at the nascent peptide exit tunnel adjacent to the peptidyl transferase centre and partially block it, which has led to the perception of macrolides as 'tunnel plugs' that halt the synthesis of all proteins[12, 13]. However, recent studies have shown that macrolides do not inhibit all proteins uniformly; instead, they selectively interfere with the translation of certain proteins. The effectiveness of macrolides is significantly influenced by the sequence of the nascent protein and the structure of the antibiotic itself[14]. For instance, two derivatives of erythromycin, each equipped with a distinct photoreactive moiety—an aryl azide or a 4-nitroguaiacol—probably have different binding sites[15]. As a result, they are better characterized as regulators of translation but not as universal inhibitors of protein synthesis.

The second mechanism of macrolides is that these antimicrobial agents, including macrolides and ketolides, achieve their bactericidal action by temporarily attaching to the 50s subunit of the ribosome in the bacteria, thereby hindering the assembly of the ribosome[16]. This interaction is able to impede RNA-dependent protein synthesis by blocking the transpeptidation and translocation processes[17, 18]. This influence of macrolides forms the foundation for the modulation of resistance gene expression.

Gaining a deeper understanding of how macrolides exert their effects could lead to the intelligent design of novel drugs and offer significant understanding of the regulation of translation processes.

4. Macrolides resistance

Shortly following erythromycin's therapeutic debut in the 1950s, resistance to this medication was detected in disease-causing agents in bacteria[19]. Of greater concern was the finding that strains resistant to erythromycin exhibited resistance not merely to all other macrolide antibiotics but also extended this resistance to include lincosamides and streptogramin B class antibiotics, which are chemically distinct. This resistance pattern was initially identified in Staphylococcus aureus and subsequently characterized as the Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin B (MLSB) antibiotic resistance profile.

The primary resistance strategies encountered in bacterial pathogens consist of two key mechanisms. First, a diminished binding affinity of the drug is observed, which results from alterations to either the bacterial ribosome or the antibiotic compound itself[20]. Second, macrolide efflux from bacterial cells emerges as another resistance method, facilitated by modifications to membrane permeability or an upregulated expression of efflux pumps[17].

There exist two classes of macrolide efflux pumps whose regulation is partly, if not fully, controlled at the transcriptional level. One such class is the mef family, belonging to the major facilitator superfamily, which imparts resistance predominantly to 14- and 15-membered macrolides. Another class is the msr family, which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and typically confers resistance to macrolides with 14- and 15-membered lactone rings, as well as to streptogramin B and provides low-level resistance to ketolides[21].

Delving deeper, the ABC-F subfamily of ATP-binding cassette transporters, to which the msr family proteins belong, plays a pivotal role in countering a wide array of clinically significant antibiotics targeting the ribosomes of Gram-positive bacteria. These transporters essentially act as shields, protecting the bacterial ribosome from the inhibitory actions of antibiotics, thereby contributing to antibiotic resistance[22].

Concurrently, the mef family, a constituent of the major facilitator superfamily, features proteins, organized around 12 transmembrane segments connected by hydrophilic loops. They are categorized into two primary subclasses, namely mef(A) and mef(E).

As to the modification of the 23S rRNA, both Gram-positive bacteria and Escherichia coli have the ability to acquire genes which have the ability to modify the 23S rRNA, resulting in high-level MLSB resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and specific streptogramin B antibiotics[23]. In specific strains of Staphylococcus aureus, erythromycin concentrations ranging from 10-8 to 10-7 M can trigger the development of resistance to levels as elevated as 10-4 M of the same antibiotic. The exposure to erythromycin will lead to expression of a methyltransferase enzyme (ErmC), which specifically methylates 23S rRNA and causes macrolide resistance[24]. Following the discovery of erm genes, an alternative mechanism of resistance through changes in rRNA structure has come to light. In laboratory experiments, it was demonstrated that single nucleotide changes in rRNA can lead to macrolide resistance. This novel type of resistance was initially detected in the singular ribosomal RNA (rrn) operon of yeast mitochondrial DNA, where a mutation occurred at position A2058 within the large subunit ribosomal RNA[25].

5. The future of macrolides

With the emergence of macrolides resistance, there is an urgent need for new antibiotics to alleviate the current situation. Possible approaches include the chemical modification of existing drugs and the discovery of new natural medicines in the natural world. Due to the different binding sites, macrolides resistance may vanish when finding new drugs[15].

5.1. Modification of existing drugs

5.1.1. Modification of erythromycin

Owing to its clinical significance and intricate molecular architecture, especially the densely packed stereocenters within the aglycon, erythromycin A poses a formidable challenge for synthetic chemists. The majority of research has focused on the stereoselective synthesis of its aglycon moiety. Additionally, chemical modifications of erythromycin A have led to the creation of several derivatives. Among these, certain semi-synthetic macrolide antibiotics like clarithromycin and azithromycin have demonstrated improved antibiotic efficacy compared to erythromycin A. The method involves 1) developing an effective synthetic pathway to produce the C1-C9 segment, intended to be a constant component in the structure of a novel macrolide, directly from erythromycin A while preserving the integrity of its two sugar components, and 2) integrating a carbon chain with the requisite functional groups into the established region and reassembling the macrolactone ring structure[26]. (Fig.2)

Figure 2. The modification of erythromycin

The interaction of erythromycin and other macrolides with metalloporphyrins along with external co-oxidants results in the substitution of the N-dimethyl moiety in the desosamine sugar, maintaining the stereochemistry intact(Fig.3), and the macrolides produced exhibit antibacterial properties. [27].

Figure 3. The structure of erythromycin with replacement of the N-dimethyl moiety in the desosamine sugar

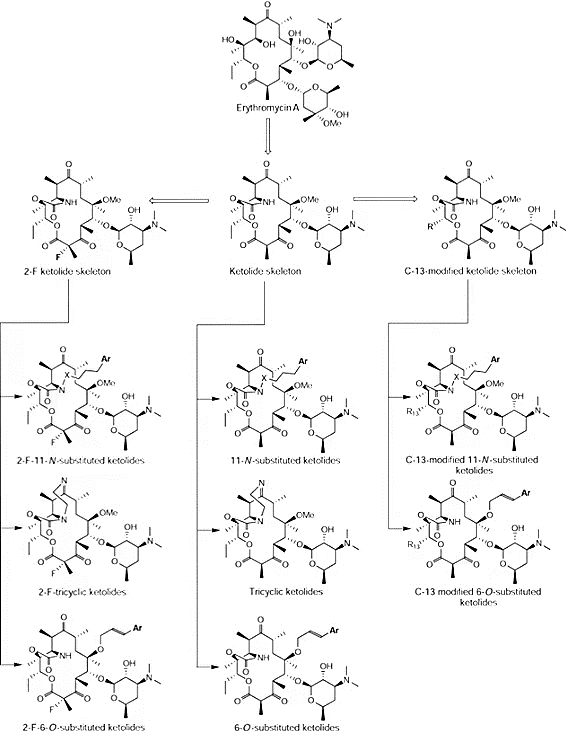

The ketolides can represent the third generation of macrolide antibiotics. These 14-membered-ring macrolides are defined by the presence of a carbonyl group at the C-3 position, a distinctive structural feature that sets them apart (Fig. 4). They are generally synthesized through the process of eliminating the cladinose sugar from the C-3 location of the erythromycin structure, followed by oxidizing the residual hydroxyl group into a carbonyl group. Some macrolides found in nature, like pikromycin, which were discovered in the 1950s, already possess the structural hallmark of ketolides.[28].

Figure 4. Subclasses of ketolides and the ketolide family tree

Up until now, every macrolide antibiotic in use originates from chemical modifications (semisynthesis) of erythromycin, a naturally occurring compound manufactured on a large scale through fermentation processes. It is obvious that there is an ongoing trend in macrolide research where more complex synthetic routes are being pursued to uncover novel derivatives. This progression underscores the escalating complexity of macrolide discovery endeavors.

5.1.2. The cross-time platform

A pivotal advancement in the field of macrolide antibiotic development and synthesis was achieved in 2016 when Seiple and his team introduced a novel strategy for total synthesis, one that is capable of producing virtually any type of macrolide compound. To be specific, they devised an unparalleled platform showcasing exceptional adaptability in the creation and synthesis of innovative macrolide antibiotics. This platform employs a design scheme centered around a multifaceted assembly process that assembles macrolides from elementary chemical components. The methodology commences with eight basic building blocks, allowing for immense variability to be integrated. These blocks proceed through a series of convergent coupling reactions, leading to the formation of two crucial intermediate compounds. These intermediates then play a vital role in the subsequent pivotal stage, the macrocyclization reaction, which is a cornerstone of their synthesis strategy. It is expected that the current synthetic platform will enable the preparation of a vast array of new macrolide structures for assessment as prospective antibiotic candidates. Considering this, it is reasonable to infer that establishing similar convergent synthetic pathways for other naturally occurring antibiotic families could expedite the identification of novel therapeutic agents to combat human infectious diseases[29].

5.2. Discoveries of new drugs

The process of drug discovery is predicated upon the systematic evaluation of bioactivity derived from natural sources, which are conventionally encompassed by microbial, fungal, and botanical entities. Natural products which are bioactive and their associated secondary metabolites have served as the principal reservoir for the development of novel therapeutic agents, frequently employed as precursors in the formulation of innovative antibiotics and anticancer drugs. With the development of technology, more drug discovering methods are developed.

5.2.1. Genome mining

In the era of genomics, characterized by an expanding repository of sequenced genomes, the integration of genome mining with synthetic biology is providing substantial assistance in the realm of drug discovery.

The term "genome mining" is synonymous with a suite of bioinformatics analyses aimed at uncovering not merely the biosynthetic pathways of natural substances which exert a biological effect on living organisms or their components, but also their possible interactions and synergies between functional aspects and chemical components. To be specific, this method entails the detection of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) which are not characterized before for natural products within the genomic sequences of organisms, the analysis of the sequences conducted to deduce the functional roles of the enzymes encoded by these genetic clusters, and the experimental validation of the output characteristics of the gene cluster products [30]. A phylogeny-directed mining strategy facilitates rapid screening of extensive microbial genomes and metagenomes to identify novel biosynthetic gene clusters of interest. Here, biosynthesis genes function as molecular signposts, and phylogenetic trees, constructed with both known and unfamiliar marker gene sequences, are instrumental in promptly selecting BGCs for metabolite characterization(Fig. 5). Observations indicate a surge in the application of this strategy in conjunction with the advent of affordable sequencing technologies over recent years[31].

Figure 5. The procedure of genome mining and heterologous expression (Adapted [32])

By utilizing this method and a public database, Morishita and coworkers conducted a polyketide synthase gene-guided fungal genome mining effort, which resulted in the discovery of a putative macrolide biosynthetic gene cluster in Macrophomina phaseolina. This distinctive gene cluster garnered attention particularly due to the integration of a notably potent reductive polyketide synthase gene, in conjunction with a thioesterase gene. The successful heterologous expression of this genetic cluster within Aspergillus oryzae, an esteemed and widely-adopted model organism for studying the biosynthesis of fungal metabolites, led to the generation of a previously unreported 12-membered macrolide compound, which has been christened as phaseolide A.[33].

5.2.2. Serendipity

The discovery of drugs can often arise serendipitously, as exemplified by the isolation of macrolides from an oceanic Micromonospora sp. strain FIMYZ51, highlighting nature's unforeseen pharmaceutical treasures.[34]. Another team claim that two previously undescribed compounds belonging to the berkeleylactone family, designated as berkeleylactones S–T, were extracted from the fungal species Penicillium egyptacum. This fungus is notable for its ability to generate the 16-membered ring macrolide antibiotic, A26771B.[35]. Keep studying natural sources, and more macrolides will be found through research on nature medicines.

6. Conclusion

Indeed, the surge in bacterial resistance poses a daunting challenge to global health, rendering the quest for new macrolide antibiotics imperative. The groundbreaking methodologies in drug synthesis, encompassing convergent synthesis pathways and the exploration of microbial genomes for novel compounds, have illuminated paths toward breakthroughs in antibiotic discovery. Moreover, the chemical tweaking of known macrolides, as seen in the progression from erythromycin to ketolides, bolsters our therapeutic options and underscores the enduring value of established drug classes.

The synergy of sophisticated synthetic systems with the biological evaluation of natural extracts highlights a potent strategy for revitalizing the macrolide antibiotic landscape. By combining the precision of advanced chemistry with the untapped riches of nature, researchers aim to unearth next-generation therapeutics capable of outmaneuvering resistant bacteria. Antimicrobial resistance, a crisis threatening to undermine decades of medical progress, may find its counterbalance in these innovative approaches.

Prospects for the future of macrolide antibiotics are imbued with optimism, fueled by the promise of relentless scientific innovation and exploration. As we continue to decode the intricacies of microbial defense mechanisms and refine our ability to synthesize complex molecules, the horizon teems with possibilities for efficacious treatments against even the most resilient bacterial foes. Through this concerted effort, the battle against antimicrobial resistance takes on a renewed vigor, heralding a new era in the annals of infectious disease control.

References

[1]. Cervin, A. and B. Wallwork, Efficacy and safety of long-term antibiotics (macrolides) for the reatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 2014. 14(3): p. 416.

[2]. Brockmann, H. and W. Henkel, Pikromycin, ein bitter schmeckendes Antibioticum aus Actinomyceten (Antibiotica aus Actinomyceten, VI. Mitteil. Chemische Berichte, 1951. 84: p. 284-288.

[3]. Kadota, J., et al., Long-term efficacy and safety of clarithromycin treatment in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Respiratory Medicine, 2003. 97(7): p. 844-850.

[4]. Johnston, S.L., Macrolide antibiotics and asthma treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2006. 117(6): p. 1233-1236.

[5]. Southern, K.W., et al., Macrolide antibiotics (including azithromycin) for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2024. 2(2): p. Cd002203.

[6]. Chittum, H.S. and W.S. Champney, Erythromycin inhibits the assembly of the large ribosomal subunit in growing Escherichia coli cells. Curr Microbiol, 1995. 30(5): p. 273-9.

[7]. Doern, G.V., et al., Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999--2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994--1995. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2001. 45(6): p. 1721-9.

[8]. Leng, M., J. Yang, and X. Liu, Macrolide-resistant mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children observed during a period of high incidence in Henan, China. Heliyon, 2024. 10(13): p. e33697.

[9]. Koide, K., et al., Genotyping and macrolide-resistant mutation of Bordetella pertussis in East and South-East Asia. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 2022. 31: p. 263-269.

[10]. Lenz, K.D., et al., Macrolides: From Toxins to Therapeutics. Toxins (Basel), 2021. 13(5).

[11]. Dinos, G.P., The macrolide antibiotic renaissance. Br J Pharmacol, 2017. 174(18): p. 2967-2983.

[12]. Wilson, D.N., Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2014. 12(1): p. 35-48.

[13]. ohmen, D., et al., SnapShot: Antibiotic inhibition of protein synthesis I. Cell, 2009. 138(6): p. 1248.e1.

[14]. Gupta, P., et al., Nascent peptide assists the ribosome in recognizing chemically distinct small molecules. Nat Chem Biol, 2016. 12(3): p. 153-8.

[15]. Arévalo, M.A., et al., Protein components of the erythromycin binding site in bacterial ribosomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1988. 263(1): p. 58-63.

[16]. Champney, S. and M. Miller, Inhibition of 50S Ribosomal Subunit Assembly in Haemophilus influenzae Cells by Azithromycin and Erythromycin. Current microbiology, 2002. 44: p. 418-24.

[17]. Zuckerman, J.M., Macrolides and ketolides: azithromycin, clarithromycin, telithromycin. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 2004. 18(3): p. 621-649.

[18]. Menninger, J.R. and D.P. Otto, Erythromycin, carbomycin, and spiramycin inhibit protein synthesis by stimulating the dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA from ribosomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1982. 21(5): p. 811-8.

[19]. Leclercq, R. and P. Courvalin, Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1991. 35(7): p. 1267-72.

[20]. Weisblum, B., Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1995. 39(3): p. 577-85.

[21]. Chancey, S.T., et al., Induction of efflux-mediated macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(7): p. 3413-22.

[22]. Sharkey, L.K., T.A. Edwards, and A.J. O'Neill, ABC-F Proteins Mediate Antibiotic Resistance through Ribosomal Protection. mBio, 2016. 7(2): p. e01975.

[23]. Roberts, M.C., et al., Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1999. 43(12): p. 2823-30.

[24]. Lai, C.J. and B. Weisblum, Altered methylation of ribosomal RNA in an erythromycin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1971. 68(4): p. 856-60.

[25]. Sor, F. and H. Fukuhara, Identification of two erythromycin resistance mutations in the mitochondrial gene coding for the large ribosomal RNA in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res, 1982. 10(21): p. 6571-7.

[26]. Nishida, A., et al., Chemical modification of erythromycin A: Synthesis of the C1–C9 fragment from erythromycin A and reconstruction of the macrolactone ring. Tetrahedron Letters, 1995. 36(18): p. 3215-3218.

[27]. Celebuski, J.E., M.S. Chorghade, and E.C. Lee, Chemical modification of erythromycin: Novel reaction observed by treatment with metalloporphyrins. Tetrahedron Letters, 1994. 35(23): p. 3837-3840.

[28]. Brockmann, H. and W. Henkel, Pikromycin, ein neues Antibiotikum aus Actinomyceten. Naturwissenschaften, 1950. 37(6): p. 138-139.

[29]. Seiple, I.B., et al., A platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics. Nature, 2016. 533(7603): p. 338-45.

[30]. Trivella, D.B.B. and R. de Felicio, The Tripod for Bacterial Natural Product Discovery: Genome Mining, Silent Pathway Induction, and Mass Spectrometry-Based Molecular Networking. mSystems, 2018. 3(2).

[31]. Kang, H.-S., Phylogeny-guided (meta)genome mining approach for the targeted discovery of new microbial natural products. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2017. 44(2): p. 285-293.

[32]. Huo, L., et al., Heterologous expression of bacterial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Natural Product Reports, 2019. 36(10): p. 1412-1436.

[33]. Morishita, Y., et al., Synthetic-biology-based discovery of a fungal macrolide from Macrophomina phaseolina. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2020. 18(15): p. 2813-2816.

[34]. Zhao, W., et al., Antimicrobial spiroketal macrolides and dichloro-diketopiperazine from Micromonospora sp. FIMYZ51. Fitoterapia, 2024. 175: p. 105946.

[35]. Zheng, X.-M., et al., Berkeleylactones S–T, novel 16-membered macrolides isolated from the endophytic fungus Penicillium egyptiacum. Natural Product Research: p. 1-7.

Cite this article

Shen,J. (2025). The future of macrolide antibiotics: Modification and new discoveries. Theoretical and Natural Science,78,264-271.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Biological Engineering and Medical Science

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cervin, A. and B. Wallwork, Efficacy and safety of long-term antibiotics (macrolides) for the reatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 2014. 14(3): p. 416.

[2]. Brockmann, H. and W. Henkel, Pikromycin, ein bitter schmeckendes Antibioticum aus Actinomyceten (Antibiotica aus Actinomyceten, VI. Mitteil. Chemische Berichte, 1951. 84: p. 284-288.

[3]. Kadota, J., et al., Long-term efficacy and safety of clarithromycin treatment in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Respiratory Medicine, 2003. 97(7): p. 844-850.

[4]. Johnston, S.L., Macrolide antibiotics and asthma treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2006. 117(6): p. 1233-1236.

[5]. Southern, K.W., et al., Macrolide antibiotics (including azithromycin) for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2024. 2(2): p. Cd002203.

[6]. Chittum, H.S. and W.S. Champney, Erythromycin inhibits the assembly of the large ribosomal subunit in growing Escherichia coli cells. Curr Microbiol, 1995. 30(5): p. 273-9.

[7]. Doern, G.V., et al., Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999--2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994--1995. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2001. 45(6): p. 1721-9.

[8]. Leng, M., J. Yang, and X. Liu, Macrolide-resistant mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children observed during a period of high incidence in Henan, China. Heliyon, 2024. 10(13): p. e33697.

[9]. Koide, K., et al., Genotyping and macrolide-resistant mutation of Bordetella pertussis in East and South-East Asia. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 2022. 31: p. 263-269.

[10]. Lenz, K.D., et al., Macrolides: From Toxins to Therapeutics. Toxins (Basel), 2021. 13(5).

[11]. Dinos, G.P., The macrolide antibiotic renaissance. Br J Pharmacol, 2017. 174(18): p. 2967-2983.

[12]. Wilson, D.N., Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2014. 12(1): p. 35-48.

[13]. ohmen, D., et al., SnapShot: Antibiotic inhibition of protein synthesis I. Cell, 2009. 138(6): p. 1248.e1.

[14]. Gupta, P., et al., Nascent peptide assists the ribosome in recognizing chemically distinct small molecules. Nat Chem Biol, 2016. 12(3): p. 153-8.

[15]. Arévalo, M.A., et al., Protein components of the erythromycin binding site in bacterial ribosomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1988. 263(1): p. 58-63.

[16]. Champney, S. and M. Miller, Inhibition of 50S Ribosomal Subunit Assembly in Haemophilus influenzae Cells by Azithromycin and Erythromycin. Current microbiology, 2002. 44: p. 418-24.

[17]. Zuckerman, J.M., Macrolides and ketolides: azithromycin, clarithromycin, telithromycin. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 2004. 18(3): p. 621-649.

[18]. Menninger, J.R. and D.P. Otto, Erythromycin, carbomycin, and spiramycin inhibit protein synthesis by stimulating the dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA from ribosomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1982. 21(5): p. 811-8.

[19]. Leclercq, R. and P. Courvalin, Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1991. 35(7): p. 1267-72.

[20]. Weisblum, B., Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1995. 39(3): p. 577-85.

[21]. Chancey, S.T., et al., Induction of efflux-mediated macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(7): p. 3413-22.

[22]. Sharkey, L.K., T.A. Edwards, and A.J. O'Neill, ABC-F Proteins Mediate Antibiotic Resistance through Ribosomal Protection. mBio, 2016. 7(2): p. e01975.

[23]. Roberts, M.C., et al., Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1999. 43(12): p. 2823-30.

[24]. Lai, C.J. and B. Weisblum, Altered methylation of ribosomal RNA in an erythromycin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1971. 68(4): p. 856-60.

[25]. Sor, F. and H. Fukuhara, Identification of two erythromycin resistance mutations in the mitochondrial gene coding for the large ribosomal RNA in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res, 1982. 10(21): p. 6571-7.

[26]. Nishida, A., et al., Chemical modification of erythromycin A: Synthesis of the C1–C9 fragment from erythromycin A and reconstruction of the macrolactone ring. Tetrahedron Letters, 1995. 36(18): p. 3215-3218.

[27]. Celebuski, J.E., M.S. Chorghade, and E.C. Lee, Chemical modification of erythromycin: Novel reaction observed by treatment with metalloporphyrins. Tetrahedron Letters, 1994. 35(23): p. 3837-3840.

[28]. Brockmann, H. and W. Henkel, Pikromycin, ein neues Antibiotikum aus Actinomyceten. Naturwissenschaften, 1950. 37(6): p. 138-139.

[29]. Seiple, I.B., et al., A platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics. Nature, 2016. 533(7603): p. 338-45.

[30]. Trivella, D.B.B. and R. de Felicio, The Tripod for Bacterial Natural Product Discovery: Genome Mining, Silent Pathway Induction, and Mass Spectrometry-Based Molecular Networking. mSystems, 2018. 3(2).

[31]. Kang, H.-S., Phylogeny-guided (meta)genome mining approach for the targeted discovery of new microbial natural products. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2017. 44(2): p. 285-293.

[32]. Huo, L., et al., Heterologous expression of bacterial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Natural Product Reports, 2019. 36(10): p. 1412-1436.

[33]. Morishita, Y., et al., Synthetic-biology-based discovery of a fungal macrolide from Macrophomina phaseolina. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2020. 18(15): p. 2813-2816.

[34]. Zhao, W., et al., Antimicrobial spiroketal macrolides and dichloro-diketopiperazine from Micromonospora sp. FIMYZ51. Fitoterapia, 2024. 175: p. 105946.

[35]. Zheng, X.-M., et al., Berkeleylactones S–T, novel 16-membered macrolides isolated from the endophytic fungus Penicillium egyptiacum. Natural Product Research: p. 1-7.