1. Introduction

In the 1980s, South Korea’s economy developed rapidly (Wu 2015). In the 1990s, the first K-pop idol group, H.O.T, caused a sensation, with young people buying peripherals, copying the styling, and even fans committing suicide when the group disbanded. Since then, hallyu (the Korean Wave) began to appear gradually in Chinese news reports. 2012 Psy’s Gangnam style swept the globe; the song was brainwashing, the dance moves were simple and easy to learn horse riding moves, strongly inspired netizens to imitate the talent and creative inspiration, countless young people have imitated the Psy’s dance poses on social media platforms. In recent years, the ensuing Korean boy and girl groups, especially the world’s hottest girl group, “BlackPink,” are successful cases of Korean pop music going global. As Korean pop culture spread from Asia to the world, it gradually became an essential perspective for studying Korean society and culture, reaching its peak in the early 21st century. At the macro level, for example, the development of K-pop is analyzed from the economic, political, and cultural perspectives (Kim 2019). There are also micro-levels, such as the phenomenon of “dollification” of Korean idols, which exploits women’s power and reduces women's mobility in the social hierarchy (Puzar 2016). Furthermore, Korean pop culture circumvents the constraints of youth protection laws, leading to negative impacts on youth idols and fans (Saeji 2013), as well as Kyong’s interviews with transnational fans to understand the influence of Korean pop music overseas and the mode of operation of the Korean pop music industry (Kyong 2017).

Since the Chinese government put forward the initiative of building the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, China has begun to emphasize the strategy of developing the country through culture. At present, Chinese scholars are conscious of the need to learn from the successful methods of the Korean wave. Wu analyzes the reasons for the spread of Korean pop music in Southeast Asia and argues that China can take advantage of the historical foundation of Chinese culture in Southeast Asia and learn from the Korean pop culture concept of “thinking globally and acting locally.”(Wu 2015) Gao compares the pop music idol groups in China and South Korea and finds that China's industry has just started, at least 20 years behind South Korea's development, so it is necessary to learn from South Korea’s mature industrial chain and direct China’s pop music market toward stable development(Gao 2020) .

At present, the literatures do not critically point out how China should learn from the industrial model of Korean pop, ignoring the problems derived from the development of Korean pop, as well as the fact that China, as a socialist country, does not have the free market of a neoliberal economy. That blind reference will not bring value to Chinese pop music. Therefore, this paper will take the Korean girl group BlackPink as a typical case, analyze the characteristics and marketing of Korean pop music, and discuss how to spread Chinese pop music while retaining China’s unique culture, avoiding copying the model and striving to make up for the shortcomings by taking advantage of the strengths, to provide positive measures for the future development prospects of Chinese pop music.

2. K-pop Success Factors

From into the 21st century, the Korean Wave began to popularize on a large scale. In 2002, the TV drama Winter Sonata set off a ratings boom in China and Japan. Not only was it popular in Asia, but Korean pop culture also gained widespread attention worldwide; Korean singers such as Rain and Wonder Girls broke out of Asia and challenged the U.S. market; new-generation idol groups such as Girls’ Generation and BEAST publicized Korean pop music globally through the U.S. video website YouTube; and in 2012, the globally-acclaimed fire of Psy’s Gangnam style, which still has 4.9 billion views on YouTube even though the video is 11 years old, and Korean boy group BTS’s digital single (Butter), which ranked No. 1 for the ninth time on the latest Hot 100 chart (Oct. 7). Bulletproof Boys’ Butter has held the No. 1 spot for seven consecutive weeks since entering the chart on Oct. 5, 2022 (chinese.korea.net 2021).

The leader of the K-pop group BTS (Kim Nam-joon) said:

“We only realized we were becoming famous once we were invited to KCONs [K-popmusic festivals] in the U.S. and Europe in 2014 or 2015. Thousands of fans were calling our name at the venue, and almost everyone memorized the Korean lyrics of our songs, which was amazing and overwhelming.” (Bruner 2017)

Kim’s remark is not an empty gesture. Nowadays, the Korean Wave has become one of the most important trendsetters of the world’s popular culture, with a wide audience and strong influence around the globe. The global popularity of the Korean Wave has driven the overall development of South Korea’s cultural industry and has also generated enormous economic benefits. In 2019, the overseas export value of South Korea’s cultural industry was 10.18903 billion US dollars, while the import value was only 1.2222 billion US dollars, with a trade surplus of up to 8.98681 billion US dollars. In 2020, the export value of South Korea’s cultural industry was 10.82741 billion US dollars, a year-on-year increase of 6.3%, which is nearly 20 times higher than the 570 million US dollars in 2000. Of particular note, the export of Korean pop music in 2020 set a record high to date. Although the world record market was hit hard by COVID-19, South Korea's record exports reached US $170 million, an increase of 94.9% over 2019 and four times over 2017 three years ago (Zhang 2021). K-pop’s globalized market has attracted countless young fans, who successively mimic their idols’ outfits and dances, and become forceful in their own fan support Teams, which are booster contributors to the K-pop economy, are more or less familiar with certain Korean idol teams, even Girls’ Generation’s “Into the New World” and BlackPink’s “As If It’s Your Last” were played at the 2019 parade of the LGBT community in Seoul, South Korea. Why has the Korean pop music industry grown to its current grandeur?

In this paragraph, I will use BlackPink, currently the most popular Korean girl group in the world, as a case study to analyze the reasons for the successful explosion of Korean pop in terms of the background of its development, musical diversity, and marketing techniques.

2.1. Background of the Development of the Korean Wave

In 1997, Asia suffered from an economic and financial crisis; the South Korean economy was hit hard, the Korean won depreciated rapidly, many industry enterprises closed down one after another, South Korea’s national into the Great Depression like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to seek help. South Korea’s various culture-related industry enterprises provided additional loans and a series of funds to help (Jia 2015), which was like a potent medicine for the recovery of the Korean economy, and the music industry finally welcomed the development. Subsequently, the government led by Kim Dae-Jung, the 15th president of South Korea, came to power and put forward the national development system of “culture as a nation” and changed the name of the Ministry of Culture and Sports to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and established the Korea Culture Content Agency (Shin and Lee 2017, 186). In order to promote a more accessible market for the cultural industry, Kim announced more supportive policies and fewer regulations, allocating more than 1% of the total budget to the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism during the Kim administration (Pak 2008, 99; Kwŏn 2012, 53). In 1999, Korea enacted the Basic Law for the Revitalization of Cultural Industries, which defines the cultural industry as “an industry that plans, researches, produces, performs, exhibits, and sells cultural goods (Li 2015). ”

Since then, the strategy of strengthening the country with culture has been made legally mandatory, and the government has invested vast amounts of money in developing cultural industries. However, because Korea is a small land area, with natural resources and population scarcity of Asian countries, the domestic market is not broad enough. If the goods are only sold to the country, the economic benefits are minimal compared with the traditional industry. The cultural sector combines the unique Korean culture and the Western new wave of cultural elements, resulting in a fusion of a brand-new Korean culture, and its novelty is favored by Asia and beyond, which makes the Korean government keenly find this breakthrough. In 2003, the 16th President of South Korea, Roh Moo Hyun, formulated a 5-year plan for Hallyu’s music industry revitalization during his term, investing 1275 billion yuan, greatly promoting the dissemination of pop music overseas (Shin and Lee, 2017, 187). This continues to promote the internationalization of South Korea’s pop music industry, expand domestic song consumption, and hold strategic measures such as multicultural activities. This indicates the South Korean government’s commitment to developing Korean pop music as an important component of the cultural industry and promoting cross-cultural dissemination of the Korean Wave. Park Geun-hye, the 18th president of South Korea, continued to uphold the purpose of vigorously developing the Hallyu, mentioning that “the second Han River miracle will be realized through Hallyu culture” (Durrer et al. 2018, 522). The Korean government has paid particular attention to intercultural communication. It has invested a great deal of money to support it, which has laid a solid foundation for Korea to explode globally.

2.2.

K-pop Music Characterization

With solid support from the government, Korean pop music has exploded in the 21st century. BlackPink, rated by Rolling Stone magazine as the world’s biggest girl group, has four members: Lisa, Jennie, Jisoo, and Rosé. BlackPink’s official YouTube page has 92.2 million followers, Lisa is the world’s hottest Korean female idol with 95.92 million followers on Instagram, and Jennie’s solo video “You & Me” has 82,499,119 views on YouTube and the numbers continue to grow. BlackPink officially debuted on August 8, 2016. Two of the songs from their first album, “SQUARE ONE,” “WHISTLE,” and “BOOMBAYAH,” reached #1 and #2 on the Billboard charts right after their release, and the entire album hit over 100 million 800 million views on Spotify. The catchy melodies and beautiful music videos have made fans worldwide go wild, and even the 44th President of the United States, Barack Obama, is a fan of Jennie’s. However, in reality, the art form of pop music started as a way to make music more accessible to the public. As time and music technology continued to evolve and audience aesthetics became more demanding, it developed the singer’s costumes, choreography, song styles, and the ideas conveyed.

Firstly, in terms of aural art, Korean entertainment companies have aurally fused a variety of European and American music styles, such as hip-hop, electronic, rock, dance music, and even classical music, fusing them with local Korean music to produce a new style of Korean pop music ultimately. For example, the first songs, “WHISTLE” and “HOW YOU LIKE THAT” of BP’s “SQUARE ONE,” use hip-hop and dance music. The whistling in “WHISTLE” combines with electronics to make the whistling sound cold and transparent, and the music sounds grotesque but addictive. The second single from “SQUARE TWO,” “STAY, ” combines country-pop stylings with a soothing, soft melody; the first single from the album “BORN PINK, ” “PINK VEEMON, ” incorporates the native Korean instrument, the Hyunhee Gum, while the music video presents shades of the American pop culture totem Britney Slave 4 U during the millennium. The second single, “SHUT DOWN,” is an excerpt from the Western classical music “La Campanella,” but the whole album presents the street culture of Europe and America, and the single “HARD TO LOVE” is a fusion of disco rhythms. Overall, BP’s songs are catchy, with repetitive chorus parts with drums and electro, as well as bass and electro air horns that hit the listener’s eardrums all the time, making one addicted to BP’s area. Secondly, in terms of visual presentation, Korean pop music, especially the hit song in an album, will carefully shoot the MV to match the style of the song. Artists must dance while showing the plot in the MV or add dance moves to the story’s development. In the period of the MV, the viewers need to pay attention to the content of the plot, the music, and the expression of the emotions in the MV. For example, “WHISTLE” shows four girls sitting in a car whistling and teasing their favorite boys, saying their love in a straightforward, subtle, sweet, and hot way, full of fluttering between men and women. However, in the second single, “BOOMBAYAH,” the four pink girls change their cute image of courting in the first single and turn into bad girls driving a motorcycle, rampaging through the world of relationships. The song is so dynamic that it will make your heart race. When your heart is pounding from the constant electronic synthesized sounds and manic electronic drums, the girl suddenly shouts “oba” in a cute tone (a word used by women to address men older than themselves. This word usually indicates a close, friendly name for a man), you will never guess what the following melody is. It will thrill every fiber of your being. Take the “KILL THIS LOVE” music video as an example. BP’s music video is colorful, with gorgeous sets and costumes, but many scenes bring a deeper meaning to the song. At the beginning, the 4 Blackpink members are standing in front of the pipe organ, which matches the background music and implies that the scene is in a church, meaning that love is as sacred as religion. Then, Rosé is driving a car that is chasing her, meaning that her love is making her suffer, and she has to kill her weak self to get away from the pain. The license plate reads “Ego,” which means that her “self” is trying to figure out how to fix all this and get back on track. The lyrics are, “I can't live with this weak self... This love must be strangled.” In the last scene, there is also a pipe organ behind where they are standing, which means “voice of God,” but the BlackPink members choose to stay away from the pipe organ, which means they decided to listen to their own heart and choose their love.

As usual, BlackPink’s MV is exquisite; it has rare explosive scenes in the MV, and the members are dressed very charmingly. Most dresses come from well-known brands such as Celine, Chanel, Versace, Alexander McQueen, Givenchy, etc., adding fashion elements to the MV. For example, Jenny and Jisoo’s white dresses represent their soft and pure hearts, while their black and white “Lola” designs symbolize their strong will and determination to break up.

2.3. Distinctive Characteristics of the Team

To more accurately express the complex and contradictory personality traits of each of them and to make bp stand out from other Korean idol groups, YG finally adopted BlackPink as the group’s name, which is meant to convey the meaning of “don’t just look at the pretty part” and “what you see is not all.” Blackpink member Rosé commented on the name of the group in an interview: “BlackPink is kind of like two colors representative of us four members. We are very girly, but at the same time, we are savage too.”

In addition to the characteristics of the team's name has shown uniqueness, comparing “SQUARE ONE” and “SQUARE TWO,” the two albums have the same form of cover, but the colors inside and out are opposite; for example, “ONE” is a pink cover with torn corners revealing a black part, while “TWO” is precisely the opposite, with the covers of the two albums and their respective contents corresponding to each other. In “ONE” album, BlackPink is on the offensive side of the relationship, seemingly passive but actually in control of the initiative. At the same time, “TWO” presents us with an image of a seemingly strong but inwardly sensitive persona, contradictory yet unified. Two of TWO’s songs lyrically show the girl’s conflicting sides very distinctly (Table 1). “PLAYING WITH FIRE” is about being desperate for love, unable to extricate oneself, and the other STAY is about being heartbroken and fragile, begging for someone to stay by her side. With two albums and four singles, BlackPink clearly showed their two contradictory sides, allowing fans to deeply remember the three-dimensional image of these four: cold, passionate, strong, and soft. Whether it is black or pink, it seems to be challenging to summarize the traits in their body comprehensively, and only the word BlackPink is an accurate and objective description of the four girls, who are both sweet and cold, leaving the audience wanting for more. But as their fame grew, they also began to receive many negative comments and even death threats, so they responded to the outside world’s questioning of their 2020 album, “HOW YOU LIKE THAT.” The song has stirring vocals, very charismatic hip-hop, and a strong sense of rhythmic movement to the group of people in deep trouble, suffering from other people’s criticism of the group dressed full of power and dynamism; the sound of hope. The song is a powerful and dynamic sound of hope, which is very much in line with the “BLACK” character of BlackPink. In 2021, BlackPink will explore career diversity and possibilities individually, with Rosé releasing her solo album “R,” Lisa releasing her single “LALISA,” and Jisoo starring in the Korean drama “Snowdrops.” Jennie is active in the fashion industry and appears in the American drama “The Idol,” starring THE WEEKND. Their talents and strengths have led them to new achievements in different fields. Although they are all members of BlackPink, they have other characteristics, reflecting that BlackPink members are both unique and united.

Table 1. Lyrics in SQUARE ONE and SQUARE TWO

SQUARE ONE(BOOMBAYAH) |

SQUARE TWO(STAY) |

Now gotta step on it, what else can I do?I'm young and fearless, manMiddle finger up, F-U pay me90's baby, I pump up the jamStep on it, step on it, oppa-ya lamboToday yours and mine, our youth's a gambleDon't dare to stop me, if anyone gets in my way.

|

You leave scars in my heart so easily with harsh words.Without even saying sorry, I comfort myself again.I'm always anxious if you're gonna leave me today.I just want you to stay.

|

2.4. Company Marketing Strategy

Behind the success of BlackPink’s global popularity, there is no shortage of YG’s marketing tactics; first of all, before the group’s official debut, they began to invest in different levels of exercise opportunities, such as Jennie’s many times to sing backing vocals for other musicians’ songs, or starring in other singers’ MVs, as well as the four’s dance video previews, the company is giving them a lot of appearances, which on the one hand, can train the artist’s experience on the stage, and on the other hand, it was also a preview for the audience to familiarize the public with their faces. After their debut, YG used starvation marketing tactics; the first step was to let the group not return for a year; the fans felt impatient and very anxious, and after a year, releasing a well-produced and long-planned single is a hazardous marketing strategy. In economics, it is a bit of scarcity principle, if a commodity or service is very scarce, then people will see this as a high-priced product, driving the demand for people to get it. YG manages to increase brand value by reducing the number of BlackPink returns. Fans are disgusted by the company's behavior, but it is a brilliant marketing concept. Although BP has not had many songs since its debut, to increase its fan base, the company has invited BlackPink to participate in various of shows, such as a program called "BlackPink House" that aired in January 2018. The program only invited four members of BlackPink, and the camera focuses on the lives of the four girls downstairs. The program shares food with the four girls, gets along with fans, learns to cook, and exaggerates walking and singing on the street. The program showcases a completely different image from the stage and MV, so although BlackPink did not release an album this year, they have brought their fans closer through the moments of life off stage, thus becoming active in people’s sight.

YG also has the ambition to promote BlackPink globally, judging from the identities of the four members: Lisa is Thai, Rosé grew up in Australia, and Jennie studied in New Zealand. All three members are very fluent in English.YG’s choice of timing for album releases has also been more internationalized, with BP releasing its physical album Square Up in June 2018, while this time around, the album was the first time chosen to be released on a Friday because the settlement time of the Korean charts is from Monday to Sunday, while the settlement time of the U.S. billboard is from every Friday to the Thursday of the following week. BP released its second mini-album, Kiss This Love, on April 5, 2019, and YG corresponded to the U.S. Universal’s request for the international market to release it at midnight worldwide. These initiatives These moves also signaled YG’s preference for the global market. To successfully penetrate the international market, BP collaborated with a large number of European and American singers, such as “Kiss and Makeup” with British female singer Dua Lipa; on May 28, 2020, BP released the collaboration song “Sour Candy” with American singer LADY GAGA, on August 28, released the collaboration song “Ice Cream,” held their first world tour in January 2019, and were invited to the Coachella Festival in the United States in April. While their fame is building, all four members of the girls have luxury endorsements; Jennie is a Chanel ambassador, a Dior brand ambassador, and a Cartier jewelry brand ambassador. Rosé endorses Tiffany & Co. and YSL, and Lisa supports Celine as a global ambassador. YG has capitalized on the symbolic value of luxury brands to elevate BP. YG company utilized the symbolic value of luxury brands to raise BP’s image to a new level, and billboards of the four of them were erected in front of luxury brand stores worldwide. Unsurprisingly, BP has swept the globe through the above-multifaceted marketing tactics.

3. The Development Path of Chinese Popular Culture

In terms of cultural roots, Chinese culture has had a profound impact on the Korean Peninsula, with geographic and cultural proximity and similar social traditions. Chinese-language record labels have followed the lead of South Korean idol groups such as “Twins” and “SHE.” Nowadays, there are many self-produced varieties show in China, such as “Idol Practitioner” created by Aqiyi (a video platform similar to YouTube in mainland China), which has recorded 3 billion broadcasts, 14 billion topics on Weibo (a social media platform similar to Instagram in mainland China), and 652 Weibo Hot Searches on the list (Gao 2020). It is essential to recognize that China’s idol group market, driven by self-produced variety shows on video websites, is gradually filling the gap between “idol groups” and “trainees” that has always existed in the country. Still, due to the late start of Chinese music industry, the overall scale of the idol group market and the number of idol groups across regions have yet to reach a critical mass. However, due to the late start of Chinese music industry, no matter the overall scale of idol groups or the cross-region and cross-culture dissemination effect, it is not comparable to Korean idol groups. This shows many problems and room for progress in local and overseas cross-cultural communication and marketing of China’s pop music. In this paragraph, I will explore the future direction of China’s pop music.

3.1. Use of Chinese Elements

Korean pop culture has indeed ensured transnational consumption, setting up a trend towards multicultural products that are transnational and transregional. In its production system and human resources, the K-pop industry has been significantly deterritorialized beyond its place of origin, South Korea (Lie and Oh 2014). However, this high degree of integration with Western music has made the elements of Korean culture not easily perceived by the audience, making it impossible to identify which language is dominant, and the chorus is often dominated by simple, easy-to-understand English lyrics, immersing the audience in a borderless pleasure of listening and consuming. Therefore, only with a high degree of recognizability can Chinese pop music instantly attract pop music audiences from other countries in the environment of cultural information explosion. Starting from a successful case of Chinese pop music, Zhang Yixing (a native of mainland China and a former member of the South Korean boy band EXO) has utilized a large number of Chinese elements in his latest album, "Lotus." First, the song uses traditional Chinese instruments such as pipa, drum, erhu, xiao, gong, and traditional Chinese Peking Opera as the opening intro in the arrangement, creating a strong Chinese-style mood. At the same time, western instruments such as tuba are used to create a low and majestic feeling. The 808 drum beats commonly used in western rap-trap music are also added to emphasize the overall rhythm of the song, which is very rhythmic. Secondly, the MV of the song is set in an ancient Chinese historical scene, dressed in traditional Chinese clothing “Hanbok” with a dragon in the center of the clothes, at last Zhang Yixing in the MV to summon out the dragon. Chinese people have always proclaimed themselves as the descendants of the dragon, and the dragon is the totem of the Chinese nation. Therefore, Zhang Yixing has skillfully integrated Chinese culture into the music video, making the whole music video like a movie about a Chinese emperor overcoming his demons.

In addition, some of Chinese TV platforms have created a fusion and collision between traditional Chinese culture and classic Chinese pop music by blending classical Chinese pop tracks with traditional ancient poems, theater songs, and other cultural elements, which are then re-sung by China's current mainstream singers. For example, in CCTV’s “Classic Songs,” famous Chinese singer Tan Weiwei fused the traditional Chinese cultural heritage of the Sichuan River Horn with modern music, and the interlude included the ocarina, a traditional Chinese musical instrument that is more than 7,000 years old, making the piece very Chinese. Due to the novelty of this creative approach and the combination of traditional Chinese culture, more young people can feel the charm of Chinese pop music. Suppose we want to realize the successful cross-cultural communication of Chinese pop music. In that case, we should first highlight the Chinese elements and let the audience feel the charm of Chinese traditional culture.

3.2. Create A Unique Concept

Korean pop music can be successful in cross-cultural communication, not only the characteristics of Korean pop music itself. K-pop, first of all, in the song title, the album concept was outstanding and unique. So, if Chinese pop music wants to achieve cross-cultural communication, the first thing to do is start with song titles, such as BP’s “KILL THIS LOVE” and “BOOMBAYAH,” which are intuitive, easy to understand, and very interesting. Let the audience see the words associated with this song, genuinely intercultural communication impact, in such an impact on the intercultural brand marketing will become smoother.

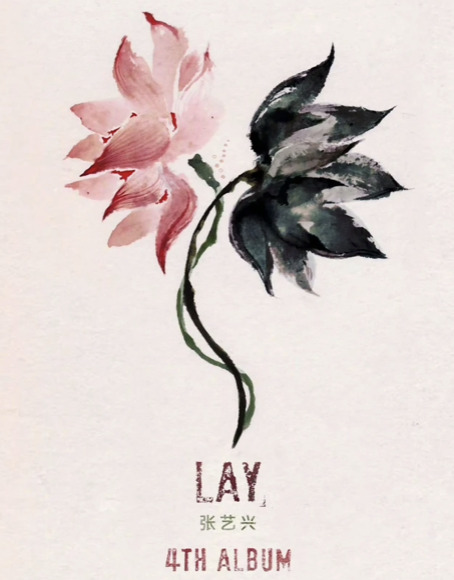

Secondly, K-pop music’s packaging of the concept and shape of the album is also almost perfect, such as the aforementioned “SQUARE ONE” and “SQUARE TWO,” which reflect the connotation of BP in the album cover, and the two albums echo each other, making it clear what the songs convey. Zhang Yixing's “Lotus” is also an excellent example of a Chinese pop album (Figure 1). On the cover of this album, a traditional Chinese ink painting of a water lily is used, and “Lotus” is meant to represent the uncommon temperament and unruly spirit of the lotus flower that “comes out of the silt and does not get stained” in traditional Chinese culture. The album cover consists of two intertwined black and red lotuses, blooming together, alluding to the concept of “Lotus is born from two sides” (baijiahao 2020). The album cover shows the Chinese character of the music and suggests that the song's main character is the same as the lotus flower. Therefore, a unique album package is attractive to the audience and can enhance consumers’ desire to buy (Cheng 2019). Music albums with distinctive features, prominent concepts, and satisfying consumers’ aesthetic experiences will catalyze the cross-cultural dissemination of Chinese pop music.

Figure 1 Zhang Yixing “Lotus” Album Cover

3.3. Protect the Rights of Youth Idols and Fans

While Korean idols are catching fire all over the world, they have also brought about a spin-off problem: the dollization of female idols, with “dollization” being defined as the fascination with dolls and behaving like them, sometimes with sexual fetishistic desires and practices towards them, or even the imagined or actual ability to turn people into dolls (Puzar 2016). The dollification of female idols has led to increasingly revealing stage attire and cameras focusing on women’s sexuality, completely “sexualizing” women, especially underage teen idols who are more vulnerable to the industry. For example, in September 2023, Lisa attended the Crazy Horse show in France, a specialized strip club. The media began to slam Lisa's behavior as a disgrace to women, but many female fans took to social media platforms to show their nudity in order to support and follow suit. “K-pop is not just about explicit displays, but also about the systematic and strategic objectification, exploitation, and degradation of women’s bodies,”(Saeji 2013) which not only inculcates consumerism, but also serves to legitimize and rationalize patriarchal gender hierarchies. They perform seductive actions on command and are brainwashed through the media. If teenagers are the recipients of these audio-visual messages, there will be self-objectifying, commodifying, and even sexualizing individuals among them.

Therefore, the improvement of relevant laws is needed to ensure the benign development of Chinese pop music. For example, the dress code for female idols should be raised to avoid revealing and sexually suggestive looks; the auditing of idol videos on online platforms should be strengthened to prevent teenagers from being induced by the content of the videos; and the national government should take strong measures to penalize companies or individuals who violate the law. National policies on the industry can also reflect the maturity of the industry’s development, and Chinese popular music must be developed in a disciplined manner to avoid the adverse effects of intercultural communication.

References

[1]. Baidu. “Zhang Yixing ‘Lotus’” Last modified June 2, 2020. [1] https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1668380628033273710&wfr=spider&for=pc

[2]. Bruner, Raisa. "Rap Monster of Breakout K-Pop Band BTS on Fans, Fame and Viral Popularity." Time.Com, 28 June 2017, p. 1. EBSCOhost, ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.edu/login url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=123845408&siteehost-live.

[3]. Durrer, Victoria and Toby Miller. The Routledge Handbook of Global Cultural Policy. Edited by Dave O\’Brien. New York: Routledge, 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315718408.

[4]. Gao Yixuan. “On the influence of Korean idol groups on Chinese pop music over the past twenty years.” People’s Music 10(2020): 86-89. ISSN:0447-6573(In Chinese)

[5]. Google. “BTS’s Butter”. Lsat modified July 7, 2021. https://chinese.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=200617

[6]. Jia Jia. Research on the Sustainable Development Capability of the Korean Popular Music Industry, Yunnan University, 2015. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201502&filename=1015610727.nh.(In Chinese)

[7]. Kim, Gooyong. “From Hybridity of Cultural Production to Hyperreality of Post-Feminism in K-Pop: A Theoretical Reconsideration for Critical Approaches to Cultural Assemblages in Neoliberal Culture Industry.” European Journal of Korean Studies, 2019.125–59. https://doi.org/10.33526/ejks.20191901.125.

[8]. Kyong Yoon. “Global Imagination of K-Pop: Pop Music Fans’ Lived Experiences of Cultural Hybridity.” Popular Music and Society 41, no. 4 (2017): 373–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1292819.

[9]. Li Chunhu.Analysis of Korea's cultural industrialization strategy and its policy inquiry. Journal of Korean Studies 02(2015): 195-213. doi:CNKI:SUN:HGYL.0.2015-02-012. (In Chinese)

[10]. Lie, John, and Ingyu Oh . “SM Entertainment and Soo Man Lee.” Handbook in East Asian Entrepreneurship. Editedy by Fu Lai Tony Yu and Ho don Yan . London: Routledge, 2014. 346–352.

[11]. Puzar, Aljosa. “Asian Dolls and The Westernized Gaze: Notes on the Female Dollification in South Korea.” Academia.edu, February 22, 2016. [11] htps://www.academia.edu/22280147/Asian_Dolls_and_the_Westernized_Gaze_Notes_on_the_Female_Dollification_in_South_Korea.

[12]. QiuYangyang. Research on the Development Status of Korean Pop Music. Harbin Normal University. 2014. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201501&filename= 1014376492.nh. (In Chinese)

[13]. SAEJI, CEDARBOUGH T. “Juvenile Protection and Sexual Objectification: Analysis of the Performance Frame in Korean Music Television Broadcasts.” Acta Koreana 16, no. 2 (2013): 329–65. doi:10.18399/ACTA.2013.16.2.003.

[14]. Shin Hyunjoon. “Controlling or Supporting? A History of Cultural Policies on Popular Music”. Made in Korea: Studies in Popular Music. Edited by Seung-Ah Lee. New York, NY ; Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315761626.

[15]. Wei Ting and Xinyung Li. “The Characteristics of Korean Pop Music Industry.” Chongqing Social Sciences 07(2015):67-72. doi:10.19631/j.cnki.css.2015.07.010. (In Chinese)

[16]. Wu Jiewei. “Analysis of the spread of Korean pop culture in Southeast Asia.” Southeast Asian Studies 06(2015):86-92. doi:10.19561/j.cnki.sas.2015.06.012. (In Chinese)

[17]. Xing Liju. Research on the institutional mechanism of Korean culture “going out”. People’s Forum 23 (2021): 90-94. doi:CNKI:SUN:RMLT.0.2021-23-021. (In Chinese)

[18]. Zhang Jianhua. “Analysis of the influence of Korean pop culture in China.” Hundreds of Artists S2(2012):4-7. ISSN:1003-9104. (In Chinese)

Cite this article

Jiang,A. (2024). Analysis of Korean Pop Music: The Enlightenment for Chinese Pop Music. Advances in Humanities Research,5,1-7.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baidu. “Zhang Yixing ‘Lotus’” Last modified June 2, 2020. [1] https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1668380628033273710&wfr=spider&for=pc

[2]. Bruner, Raisa. "Rap Monster of Breakout K-Pop Band BTS on Fans, Fame and Viral Popularity." Time.Com, 28 June 2017, p. 1. EBSCOhost, ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.edu/login url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=123845408&siteehost-live.

[3]. Durrer, Victoria and Toby Miller. The Routledge Handbook of Global Cultural Policy. Edited by Dave O\’Brien. New York: Routledge, 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315718408.

[4]. Gao Yixuan. “On the influence of Korean idol groups on Chinese pop music over the past twenty years.” People’s Music 10(2020): 86-89. ISSN:0447-6573(In Chinese)

[5]. Google. “BTS’s Butter”. Lsat modified July 7, 2021. https://chinese.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=200617

[6]. Jia Jia. Research on the Sustainable Development Capability of the Korean Popular Music Industry, Yunnan University, 2015. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201502&filename=1015610727.nh.(In Chinese)

[7]. Kim, Gooyong. “From Hybridity of Cultural Production to Hyperreality of Post-Feminism in K-Pop: A Theoretical Reconsideration for Critical Approaches to Cultural Assemblages in Neoliberal Culture Industry.” European Journal of Korean Studies, 2019.125–59. https://doi.org/10.33526/ejks.20191901.125.

[8]. Kyong Yoon. “Global Imagination of K-Pop: Pop Music Fans’ Lived Experiences of Cultural Hybridity.” Popular Music and Society 41, no. 4 (2017): 373–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1292819.

[9]. Li Chunhu.Analysis of Korea's cultural industrialization strategy and its policy inquiry. Journal of Korean Studies 02(2015): 195-213. doi:CNKI:SUN:HGYL.0.2015-02-012. (In Chinese)

[10]. Lie, John, and Ingyu Oh . “SM Entertainment and Soo Man Lee.” Handbook in East Asian Entrepreneurship. Editedy by Fu Lai Tony Yu and Ho don Yan . London: Routledge, 2014. 346–352.

[11]. Puzar, Aljosa. “Asian Dolls and The Westernized Gaze: Notes on the Female Dollification in South Korea.” Academia.edu, February 22, 2016. [11] htps://www.academia.edu/22280147/Asian_Dolls_and_the_Westernized_Gaze_Notes_on_the_Female_Dollification_in_South_Korea.

[12]. QiuYangyang. Research on the Development Status of Korean Pop Music. Harbin Normal University. 2014. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201501&filename= 1014376492.nh. (In Chinese)

[13]. SAEJI, CEDARBOUGH T. “Juvenile Protection and Sexual Objectification: Analysis of the Performance Frame in Korean Music Television Broadcasts.” Acta Koreana 16, no. 2 (2013): 329–65. doi:10.18399/ACTA.2013.16.2.003.

[14]. Shin Hyunjoon. “Controlling or Supporting? A History of Cultural Policies on Popular Music”. Made in Korea: Studies in Popular Music. Edited by Seung-Ah Lee. New York, NY ; Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315761626.

[15]. Wei Ting and Xinyung Li. “The Characteristics of Korean Pop Music Industry.” Chongqing Social Sciences 07(2015):67-72. doi:10.19631/j.cnki.css.2015.07.010. (In Chinese)

[16]. Wu Jiewei. “Analysis of the spread of Korean pop culture in Southeast Asia.” Southeast Asian Studies 06(2015):86-92. doi:10.19561/j.cnki.sas.2015.06.012. (In Chinese)

[17]. Xing Liju. Research on the institutional mechanism of Korean culture “going out”. People’s Forum 23 (2021): 90-94. doi:CNKI:SUN:RMLT.0.2021-23-021. (In Chinese)

[18]. Zhang Jianhua. “Analysis of the influence of Korean pop culture in China.” Hundreds of Artists S2(2012):4-7. ISSN:1003-9104. (In Chinese)