1. Introduction

Folk crafts are products of historical and cultural accumulation. They indirectly reflect the lifestyle and cultural beliefs of the laboring masses in a region, serving as specific cultural symbols that document the developmental journey of a particular area during certain periods [1]. Additionally, folk crafts are an important component of regional folk culture, typically representing the crystallization of the wisdom and cultural heritage of the local working people. Through the creation and inheritance of handicrafts, people maintain a connection with their own culture and historical traditions. This contributes to shaping and maintaining local identity, passing on cultural values and techniques from one generation to the next. Likewise, folk crafts serve as a medium of cultural expression, often reflecting the local society's religious customs, history, and values. These crafts can be both artworks and everyday items, but all carry cultural messages. Therefore, the relationship between regional culture and local folk crafts is complex and multidimensional: it not only reflects culture but also promotes its continuity and development, profoundly affecting society, economy, and identity. This paper takes the folk crafts of Southern Fujian—specifically the porcelain produced by Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kilin—as examples to analyze the influence of Southern Fujian religious folk customs on folk crafts.

2. Craftsmanship Characteristics of Quanzhou Dehua Kiln White Porcelain

2.1. Historical Origins of Dehua Kiln

Dehua Kiln is renowned for its white porcelain, which originated from white pottery. Historical records indicate that white pottery was already formed during the late Neolithic period, and over time it evolved into glazed pottery, primitive celadon, and ultimately into the category of white porcelain. Dehua Kiln has followed the grand historical trajectory: starting from the Tang dynasty, it successively produced Tang celadon, Song dynasty Qingbai porcelain, Yuan dynasty white porcelain, and reached its pinnacle with Ming dynasty white porcelain, particularly exemplified by the works of the craftsman He Zhaozong. This established Dehua Kiln's primary focus on firing white porcelain, setting the folk kiln style known as the "White Brow" [2] of folk kilns. Hence, this article takes the white porcelain produced by Dehua Kiln as a typical case for analysis.

2.2. Craftsmanship Characteristics of Dehua Kiln White Porcelain

Dehua Kiln white porcelain is noted for its remarkable translucency and visual effect, appearing exceptionally smooth and translucent under light, resembling jade; the porcelain also presents a subtle yellowing and pinkish milky-white coagulated cream color. Exploring how Dehua Kiln white porcelain achieves this "lustrous color and milky appearance as coagulated cream" aesthetic, which concentrates significant aesthetic value, is believed to be closely linked to the materials used in the kiln.

From a materials perspective, Dehua Kiln white porcelain comprises body and glaze materials. The porcelain's body is dense, utilizing clay rich in silica and other fluxes that aid in the melting of silica; on the other hand, the clay's potassium oxide content is as high as 6%, resulting in a higher proportion of glass phase after firing in a neutral atmosphere. The glaze materials used in Dehua Kiln white porcelain come from the same clay—this characteristic ensures that Dehua Kiln porcelain maintains a pure and clean white glaze color, with the body and glaze bonding well [3].

Another aspect of Dehua Kiln white porcelain's craftsmanship is its unique modeling techniques, which have evolved on the foundation of traditional Chinese carving skills. These include handmade molding techniques such as hand-pinching, carving, stacking, applying, and trimming. These techniques allow ceramic artisans to intricately carve and shape the porcelain, achieving unique appearances and decorations. Moreover, inspiration is drawn from other folk crafts in the Southern Fujian region, including clay sculpting, wood carving, and stone carving. This cross-disciplinary exchange of skills promotes continual innovation and development in techniques, also giving Dehua white porcelain more vivid visual characteristics, thus earning high praise for both decorative and practical uses.

Figure 1. Qing Dynasty Dehua Kiln white glazed plum blossom cup [Source: “A Brief Discussion on the Role of Ancient White Porcelain in International Cultural Exchanges—from Tang Dynasty Xing Kiln to Ming and Qing Dynasty Dehua Kiln” [4]]

Figure 2. Ming Dynasty white glazed molded Chi dragon pattern straight cylinder-style pitcher [Source: “Investigation of Ming Dynasty Dehua Kiln Molded Chi Dragon Pattern Straight Cylinder-style Pitcher” [5]]

3. Craftsmanship Characteristics of Zhangzhou Kiln

3.1. Origins of Zhangzhou Kiln

Regarding the documentation of the "Zhangzhou Kiln" lineage, Yang Xun's "Records of Zhangzhou" states: "The Zhangzhou ceramics known as 'Dongxi wares' originated in the former Ming dynasty, producing various styles including bottles, furnaces, and plates" [6].

Before the archaeological site of Dongxi Kiln in Zhangzhou was excavated, Zhangzhou Kiln generally referred to the kilns located in the middle reaches of the Jiulong River in Zhangzhou in southern Fujian, dating from the late Ming dynasty to the early Qing dynasty. These kilns were primarily located in present-day Pinghe, Zhangpu, Nanjing, Hua'an, Yunxiao, and Zhao'an counties, and excavations uncovered ceramics mainly decorated with blue and white and plain tricolor glazes, as well as single-color glaze and multicolored everyday utensils [7]. Recent continued interest and research into Zhangzhou Kiln have led to the discovery of true Zhangzhou Kiln ceramics—beige-glazed pottery [8].

3.2. Craftsmanship Characteristics of Beige-Glazed Pottery from Zhangzhou Kiln

A distinctive feature of Zhangzhou Kiln ceramics, setting them apart from other kiln products, is the glaze color of Zhangzhou Kiln's "white glaze with a beige tint," characterized by a white glaze with a yellowish tinge. The variety in glaze colors of Zhangzhou Kiln is another distinct feature that differentiates it from other kiln products. Apart from standard traditional tones, Zhangzhou Kiln glazes also come in many visual forms, with different glaze areas showing different colors, some are yellow-brown, others are gray-brown. The varied tones of Zhangzhou Kiln glazes are due to natural minerals like lime and quartz undergoing high-temperature firing in the kiln. Additionally, the "rice" in Zhangzhou beige-glazed does not only refer to the "rice" color of the glaze but is also reflected in the rice-grain-like craquelure in the glaze. Due to the differences in the expansion coefficients of the clay used for the body and the glaze, extensive craquelure appears on the glaze during firing. The cracks vary in thickness, sparse or faint and evenly distributed on different ceramics, resembling fine fish scales, with the smallest craquelure patterns like sesame seeds, most commonly fine like rice grains. Although Zhangzhou Kiln's body and glaze are highly charming, they are not easily distinguishable from Jingdezhen ceramics. The techniques, carvings, and decorative patterns of Zhangzhou Kiln share similarities with Jingdezhen pottery but also aim for a subtle aesthetic beauty.

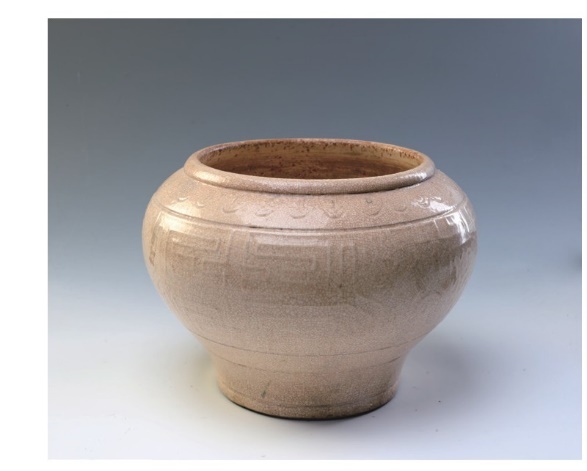

Figure 3. Late Ming Dynasty Zhangzhou Kiln Kui Dragon Pattern Jar [Source: "Appreciation of Zhangzhou Kiln Ceramics in the Collection" [9]]

Figure 4. Mid-Qing Dynasty Zhangzhou Kiln Relief Molded Windowed Pavilion Pattern Jar [Source: "Appreciation of Zhangzhou Kiln Ceramics in the Collection" [9]]

4. The Influence of Religious Folk Customs on Southern Fujian Folk Crafts

Religious folk customs significantly impact folk crafts, evident in various aspects, including craftsmanship, design style, craft inheritance, and the uses and symbolic meanings of folk crafts [10].

4.1. Influenced by Religion

Religion has profoundly influenced the craftsmanship of Southern Fujian crafts. The belief systems and ceremonial requirements of different religions are often reflected in the design of folk crafts, particularly in religious statues and ritual implements. These religious requirements often drive innovation and improvement in crafts to ensure they align with religious doctrines. Both Quanzhou and Zhangzhou have long-standing religious traditions, including Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. These religious beliefs are deeply revered and inherited by the people of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou. While there may be specific differences in religious ceremonies and temple fairs, they are rooted in common religious values that emphasize morality, reverence, and spirituality.

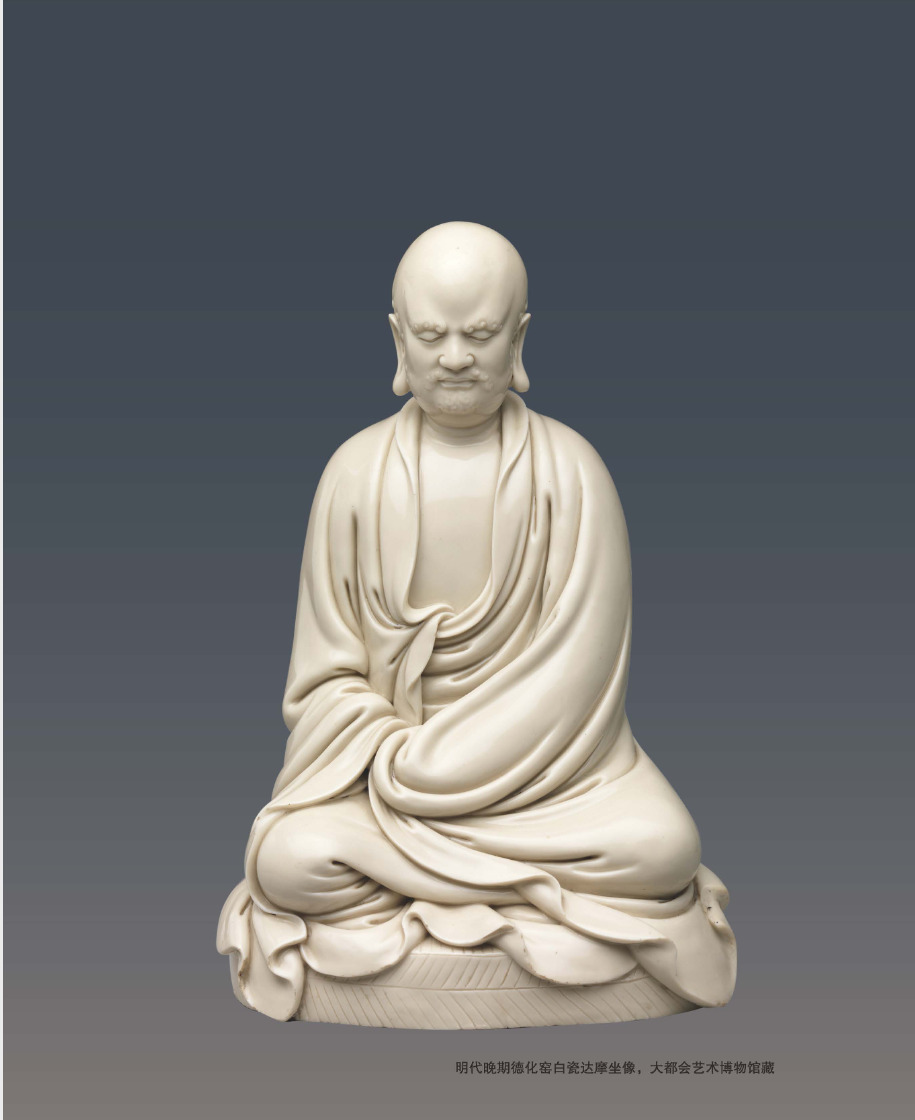

4.1.1. Influenced by Buddhism

Southern Fujian has been a flourishing center of Buddhism since ancient times, historically producing many eminent monks and devoted lay protectors. Zhu Xi once praised Quanzhou by saying, "This place was anciently known as the land of Buddha, where saints fill the streets." Buddhist doctrines, emphasizing the cultivation of the soul, compassion, and the aspirations of Bodhisattvas, have found widespread acceptance in Southern Fujian. Buddhism entered Fujian around the period of the Three Kingdoms and Wu Jin and saw rapid development by the Liang dynasty. By the Song dynasty, Buddhism in Fujian had reached its zenith. By the Ming dynasty, Buddhism in Fujian had subsided to a more subdued level. During the Republic of China period, the patriotic Buddhist master Hong Yi revitalized the Buddhist culture in Southern Fujian during his travels to its famous mountains and rivers.

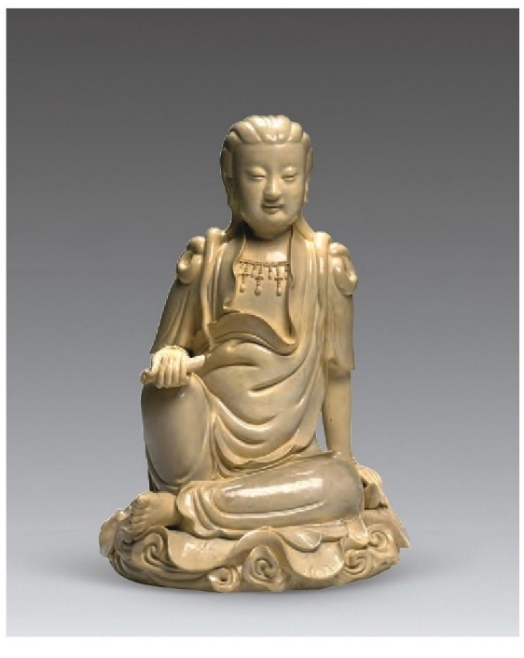

Buddhist beliefs have profoundly influenced the religious festivals and ceremonies in the Southern Fujian region. Both Quanzhou and Zhangzhou have rich Buddhist heritages. Quanzhou is famous for its unique Buddhist temples and temple fairs, such as the Kaiyuan Temple and Chengtian Monastery, which serve not only as religious sites but also as centers of culture and art. Zhangzhou also has numerous Buddhist temples, such as Nanshan Temple and Qishouyan Temple, and vibrant temple fairs and religious ceremonies, such as Buddha's Birthday and Guanyin's Birthday. These Buddhist festivals have become significant religious and cultural events. Temple fairs are also vital venues for religious faith and cultural exchange in Southern Fujian. These fairs are not only religious activities but also social and cultural events where various folk traditions, performances, and crafts are showcased, enriching the region's cultural life. Therefore, Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kiln productions incorporate the Buddhist beliefs, moral views, and cultural heritage of the people in Southern Fujian, also integrating local cultural elements, thus shaping the ceramics featuring Buddha, Bodhisattvas, Arhats, Heavenly Kings, and Vajra as one of the primary creative themes.

Figure 5. Dehua Kiln White Porcelain Statue of Dharma [Source: "Late Ming Dynasty Dehua Kiln White Porcelain Statue of Dharma" [11]]

Figure 6. Zhangzhou Kiln Beige-Glazed Statue of Guanyin [Source: "A New Interpretation of the Inscription on a 'Da Ming Wanli Yi Mao Year' Zhangzhou Kiln Porcelain Sculpture" [7]]

4.1.2. Influenced by Taoism

Taoism was introduced into Fujian during the Eastern Han dynasty and gained prominence with the establishment of the Li family's Tang dynasty, during which Laozi (Li Er) was worshipped as an ancestor by the Li imperial family. This initiated a wave of Taoism in the court and among the public, demonstrating loyalty and devotion to the monarch and marking the rise of Taoism. The religion flourished further during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period and peaked again during the Song and Ming dynasties. The Taoist myth of the "Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea" includes Cao Guojiu, who was based on Cao Yi, the brother of Empress Cao during the reign of Emperor Renzong of Song. The Jiajing Emperor of the Ming dynasty also spurred a Taoist revival by promoting the teachings of Huang-Lao; and the Ming dynasty classic "Journey to the West" includes detailed descriptions of folk Taoist activities. In Quanzhou, the "Tonghuai Guandi Temple" and "Gushan Taoist Temple," and in Zhangzhou, the "Dongshan Guandi Temple" and "Nanshan Temple," are among the prominent centers of Taoist activities in the Southern Fujian area. As an indigenous Chinese religion, Taoism offers blessings and promises prosperity to families who worship on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month, with widespread belief in karma and reincarnation in Fujian. Meanwhile, numerous Taoist temples are scattered throughout Southern Fujian, including the Song dynasty's Baiyun Temple, now known as "Yuanmiao Temple"; the Dongyue Palace under Dongfeng Mountain in Quanzhou; and the "Fengxia Ancestral Palace" in Xiangcheng District, Zhangzhou, where the Taoist deity Xuantian Shangdi is primarily worshipped.

The works from both Zhangzhou Kiln and Dehua Kiln have been deeply influenced by centuries of folk customs. The white porcelain of Dehua Kiln, especially the pieces crafted by the Ming dynasty artisan He Chaozong, represents the pinnacle of Dehua Kiln's white porcelain craftsmanship. One of He Chaozong's representative works is his seated statue of Wenchang Dijun. The belief in Wenchang Dijun originated from Zhang Yazi, a heroic general from the Southern and Northern Dynasties who defended Shu against the Former Qin. This belief spread from Sichuan during the Song dynasty with the legend of the "Zitong Dream," which claimed that dreams sent by the Zitong deity could predict success in the imperial examinations [12]. This was linked with the Taoist belief in the Wenchang Palace, which governed literature and stars, leading to the integration of Zitong deity with Wenchang god during the Southern Song dynasty, solidifying Wenchang Dijun's celestial status as overseer of the imperial examination culture. Under the Ming dynasty's culture of valuing literature, worship of Wenchang Dijun spread nationwide, with scholars and candidates praying to him for examination success, a practice that continues today. In his porcelain work, He Chaozong meticulously depicted the decorative patterns of Wenchang Dijun's robes, with varying depths and interwoven structures making the robes seem realistic and lively, thereby bridging the psychological distance between the deity and his worshippers.

Figure 7. He Chaozong's Wenchang Jun Statue from Dehua Kiln [Source: "A Brief Discussion on the Role of Ancient White Porcelain in International Cultural Exchanges—from Tang Dynasty Xing Kiln to Ming and Qing Dynasty Dehua Kiln" [4]]

Figure 8. Zhao Gongming Standing Statue from Zhangzhou Kiln [Source: "A New Interpretation of the Inscription on a 'Da Ming Wanli Yi Mao Year' Zhangzhou Kiln Porcelain Sculpture" [7]]

Furthermore, examining a Taoist-themed piece from Zhangzhou Kiln, a beige-glazed statue of Zhao Gongming, the God of Wealth, housed in the Hongxi Art and Education Foundation reveals an inscription at the base stating that the porcelain was a ritual offering from Quanzhou's Kaiyuan Temple, engraved with "Faithful Lin Shi Shi hundred kowtows." This inscription, combined with the surname customs of the time, suggests that this statue was likely custom-ordered by a woman from the Shi family who married into the Lin family, seeking divine favor for wealth and safety at Kaiyuan Temple.

4.2. Influenced by Folk Customs

Folk customs, also known as traditional local customs, encompass the broadly defined social customs within a specific region: a collective pattern of life or group behaviors that include prevailing social practices, rituals, and habits passed down through generations [13]. In Southern Fujian, folk customs have played a crucial role in shaping handicrafts, with many local customs involving the creation and display of crafts, integrating these into the fabric of Southern Fujian's folk culture. The environment and social concepts of Southern Fujian profoundly influence the local people, resulting in folk customs that differ significantly from those in other regions of Fujian, based on their unique practices of life and labor.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the developed maritime trade in Quanzhou and Zhangzhou led to higher production levels in coastal towns, which in turn influenced local folk customs towards "increasingly luxurious expenses." This shift led to an enhancement in the variety of handicrafts, and people began to seek greater refinement in their everyday items. In Quanzhou, the "Jiajing Annals of Anxi County – Customs" noted: "Recently, extravagance prevails, expenses are wasteful, and while the people barely make do, the markets buzz with the activities of enjoying flowers and birds, playing musical instruments into the night, gradually losing the spirit of simplicity" [14]. On the other hand, in Zhangzhou, "a hundred trades cluster" in the town, indicating advanced commerce and a bustling atmosphere, "with grand residences stretching to the clouds, brightly colored beams, competing in beauty, rich in stones along the coast, and courts meticulously arranged, demonstrating fine craftsmanship" [15].

Historical descriptions of the lavishness of everyday items used by the people in Quanzhou and Zhangzhou during these times illustrate the region's emphasis on folk customs, with local handicrafts also serving as expressions of folk culture. Ceramics, as one of the most common household items, naturally represent typical examples of folk culture. Both Zhangzhou and Dehua kilns produce a large array of domestic utensils such as plates, bowls, cups, saucers, jars, and pots, each with richly detailed patterns, motifs, and shapes.

4.3. Summary

Against the backdrop of diverse religious beliefs and folk cultures, Southern Fujian's folk crafts have thrived, drawing from a continuous cultural heritage. These crafts vary in style and characteristics across different regions but are all rooted in local folk culture, deeply cherished by the masses, and add a unique charm to the local culture. Although the Zhangzhou area is renowned for its rich Hakka culture, exemplified by the famous earthen buildings, these ancient structures represent the architectural art and communal living style of the Hakka culture. Meanwhile, Quanzhou highlights its marine culture. As a coastal city, Quanzhou's long history of maritime trade has profoundly influenced its culture. However, most of Southern Fujian's culture tends towards uniformity, also boasting many other traditional crafts like porcelain carving, wood carving, and Kinmen embroidery. These traditional cultural achievements represent unique local cultural inheritances, passed down through handicrafts, traditional festivals, architecture, and religious ceremonies, enriching the regional cultural content [16]. These folk crafts are not only popular but also original; they integrate local history, traditions, and lifestyles, profoundly influencing local culture and becoming precious assets of cultural heritage.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

5.1. Conclusion

The religious beliefs and folk customs of Southern Fujian endow handicrafts with unique symbolic meanings and uses. Many crafts play significant roles in religious ceremonies and folk customs, serving important functions. These crafts are not only practical but also carry the symbolic meanings of religious and folk traditions, enhancing their cultural value and status. Regardless of how Zhangzhou Kiln and Dehua Kiln have evolved, their core essence— the aspiration for a better life—remains constant. A deeper appreciation allows us to recognize the regional cultural characteristics inherent in both Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kiln. Exploring the connections between religious beliefs and folk customs in the manifestation of local handicrafts not only clarifies their development but also highlights the intricate relationships between culture and society, economy, and culture in the Southern Fujian region.

In summary, religion and folk customs play an indispensable role in the formation and development of local handicrafts and cultural traditions. They influence the craftsmanship, design style, and the transmission of crafts, as well as the symbolic meanings and uses of handicrafts, together forming the unique cultural traditions of the region. These crafts are not just artworks; they are carriers of culture and witnesses to history.

5.2. Future Outlook

Currently, the products produced by Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kiln are still predominantly traditional decorative items and utensils, but this overlooks the fact that the craft processes themselves represent an intangible heritage. Innovating and redesigning the folk craft culture of Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kiln can break the deadlock of homogenization and uniformity in their products, integrating traditional porcelain ornaments and utensils into modern life. By enhancing innovative modes of disseminating traditional folk crafts, we can better promote and protect these Southern Fujian folk crafts.

References

[1]. Cheng, S. (2012). Analysis of Diversity in Packaging of Folk Crafts (Doctoral dissertation, Qingdao University).

[2]. Yu, L. P. (2021). The Life of Art Lies in Innovation—On the Blanc-de-Chine and Blue-and-White Porcelain of Dehua Kiln. Ceramic Science and Art, 55(04), 22-23.

[3]. Huang, J. (2020). Analysis of the Shape, Reasons, and Influence of Ming and Qing Dehua Blanc-de-Chine Exported Porcelain. Museum, (01), 51-59.

[4]. Yao, Y., & He, K. (2022). On the Role of Ancient Blanc-de-Chine in Cultural Exchange—From Xing Kiln in the Tang Dynasty to Dehua Kiln in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Oriental Collection, (04), 5-8.

[5]. Liu, H. X. (2022). Exploration of the Straight Cylinder Flask with Bas-Relief Coiled Dragon Pattern of Dehua Kiln in the Ming Dynasty. Ceramic Science and Art, 56(11), 40-41.

[6]. Lin, J., & Zhao, M. X. (2004). Discussion on Zhang Kiln through the Ages. Collector's World, (02), 25-28.

[7]. Zhang, M. (2018). New Interpretation of Inscriptions on Zhang Kiln Porcelain of "Wanli Year of the Great Ming" from the China National Museum. Journal of the National Museum of China, (02), 131-141.

[8]. Ouyang, G. L. (2015). Discussion on the Blanc-de-Chine Porcelain Sculptures of Figures in Rice Color Glaze from Fujian Zhang Kiln in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Collector, (05), 61-64.

[9]. Zhang, L. L. (2020). Appreciation of Zhang Kiln Porcelain in the Collection. Cultural Relics Identification and Appreciation, (11), 5-11.

[10]. Zhu, S. Y. (2023). Research on the Design of Tihu Making from the Perspective of Folklore (Doctoral dissertation, Jingdezhen Ceramic University).

[11]. Blanc-de-Chine Seated Statue of Bodhidharma in the Late Ming Dynasty. Oriental Collection, (23), 114.

[12]. Zhang, Z. H. (2005). On the Worship of Wenchang Emperor in Daoism. Chinese Cultural Research, (03), 1-9.

[13]. Zhang, Y. (2021). Study on Local Officials and Social Customs Changes in the Song Dynasty (Doctoral dissertation, Henan University).

[14]. Xu, H. (2007). Changes in Social Customs in Fujian Province during the Ming Dynasty. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (05), 34-44.

[15]. Zhao, J. Q. (2006). Analysis of Luxurious Consumption Trends in Fujian Region during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (01), 134-139.

[16]. Chen, F. (2020). Research on the Temporal and Spatial Distribution, Influencing Factors, and Protection Strategies of Minnan Historical and Cultural Heritage (Doctoral dissertation, Huaqiao University).

Cite this article

Zeng,Y.;Yang,W. (2024). A Preliminary Analysis of the Influence of Southern Fujian Religious Folk Customs on Folk Crafts—Taking Dehua Kiln and Zhangzhou Kiln as Examples. Advances in Humanities Research,6,13-18.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cheng, S. (2012). Analysis of Diversity in Packaging of Folk Crafts (Doctoral dissertation, Qingdao University).

[2]. Yu, L. P. (2021). The Life of Art Lies in Innovation—On the Blanc-de-Chine and Blue-and-White Porcelain of Dehua Kiln. Ceramic Science and Art, 55(04), 22-23.

[3]. Huang, J. (2020). Analysis of the Shape, Reasons, and Influence of Ming and Qing Dehua Blanc-de-Chine Exported Porcelain. Museum, (01), 51-59.

[4]. Yao, Y., & He, K. (2022). On the Role of Ancient Blanc-de-Chine in Cultural Exchange—From Xing Kiln in the Tang Dynasty to Dehua Kiln in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Oriental Collection, (04), 5-8.

[5]. Liu, H. X. (2022). Exploration of the Straight Cylinder Flask with Bas-Relief Coiled Dragon Pattern of Dehua Kiln in the Ming Dynasty. Ceramic Science and Art, 56(11), 40-41.

[6]. Lin, J., & Zhao, M. X. (2004). Discussion on Zhang Kiln through the Ages. Collector's World, (02), 25-28.

[7]. Zhang, M. (2018). New Interpretation of Inscriptions on Zhang Kiln Porcelain of "Wanli Year of the Great Ming" from the China National Museum. Journal of the National Museum of China, (02), 131-141.

[8]. Ouyang, G. L. (2015). Discussion on the Blanc-de-Chine Porcelain Sculptures of Figures in Rice Color Glaze from Fujian Zhang Kiln in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Collector, (05), 61-64.

[9]. Zhang, L. L. (2020). Appreciation of Zhang Kiln Porcelain in the Collection. Cultural Relics Identification and Appreciation, (11), 5-11.

[10]. Zhu, S. Y. (2023). Research on the Design of Tihu Making from the Perspective of Folklore (Doctoral dissertation, Jingdezhen Ceramic University).

[11]. Blanc-de-Chine Seated Statue of Bodhidharma in the Late Ming Dynasty. Oriental Collection, (23), 114.

[12]. Zhang, Z. H. (2005). On the Worship of Wenchang Emperor in Daoism. Chinese Cultural Research, (03), 1-9.

[13]. Zhang, Y. (2021). Study on Local Officials and Social Customs Changes in the Song Dynasty (Doctoral dissertation, Henan University).

[14]. Xu, H. (2007). Changes in Social Customs in Fujian Province during the Ming Dynasty. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (05), 34-44.

[15]. Zhao, J. Q. (2006). Analysis of Luxurious Consumption Trends in Fujian Region during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (01), 134-139.

[16]. Chen, F. (2020). Research on the Temporal and Spatial Distribution, Influencing Factors, and Protection Strategies of Minnan Historical and Cultural Heritage (Doctoral dissertation, Huaqiao University).