1 Introduction

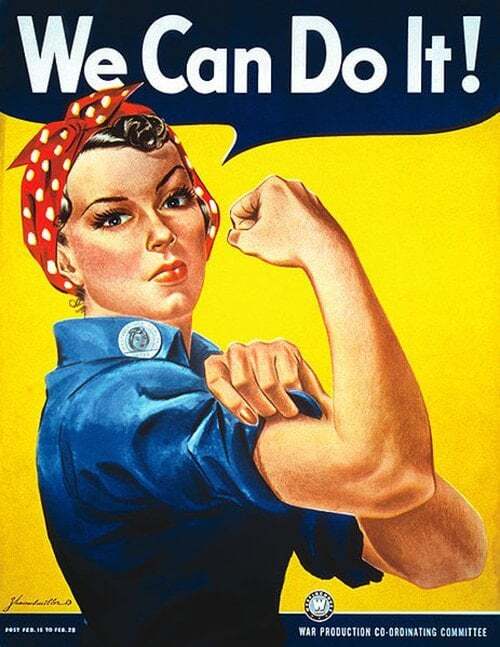

The ‘pictorial turn’, a term coined by art historian and critic W.J.T. Mitchell, has led to a radical reconsideration of the role of images in modern culture and contemporary scholarship. While for a long-time text was the dominant form of communication and meaning-making in academia, Mitchell’s theory has influenced many fields like art history, media studies and cultural theory to reconsider images as agents of communication that should not be subordinated to language but have the power to create and influence social realities on their own accord. This shift in mentality is also important in today’s era of digital modernity, where images dominate screens and public spaces, and the ability to comprehend how visuals communicate in new ways has become a central issue. One of the aims of the pictorial turn is to make scholars and the public in general more aware of the power of images to create public opinion, define identity and construct memories, as Mitchell has stated that ‘[i]mages possess an exemplary power, the power to shape a culture’s understanding of itself by embodying and enacting a politics of vision.’ This paper aims to outline the philosophical foundations of the pictorial turn by examining how images function as powerful agents of persuasion in politics, commercial advertising and other arenas. Drawing from key examples such as the poster of Rosie the Riveter and contemporary advertisements, this study demonstrates what the phenomenon of visual rhetoric looks like in traditional as well as digital media environments [1]. The paper will also discuss the agency that images have within social memory and identity formation in a society that is heavily influenced by visual culture, and the role of pictures in the construction of meaning in the digital age.

2 The Conceptual Foundations of the Pictorial Turn

The impact of this has implications for how we think about the role of images in contemporary society and scholarly research. W.J.T. Mitchell’s theory of the pictorial turn offers a framework to redefine the role of images as active participants in social and cultural reality. In his book Picture Theory (1994), Mitchell argues that images are theatres of performativity. They address their subjects on multiple levels, including emotional and perceptual ones. Mitchell proposes a shift away from the semiotic model of the image as a subordinate supplement to the word, responding to the proliferation of images within technology and media. Mitchell suggests that images are no longer just a supplement to text, but can exist as independent forms of expression. By understanding images as a form of theatre, Mitchell invites scholars to rethink how they engage with visual culture [2]. He encourages scholars to think more interdisciplinarily, with a clear acknowledgement of the ways that images can communicate through different modalities and embodiments to offer unique forms of knowledge. The pictorial turn calls for scholars to start thinking about the image as an active participant in the making of social reality. This suggests that there are distinct modalities and embodiments that are integral to the visual image in forming knowledge.

2.1 Image as Agency in Cultural Contexts

Figure 1. Rosie the Riveter: Icon of Empowerment and Cultural Transformation (Source: wordpress.com)

One of the most profound contributions of Mitchell’s theory is that images act, that is, they participate in the making of cultural and social realities. Until recently, it was more common to view images as reflective and secondarist, as the way of seeing the world, or at most as symbolic of what the word describes. Mitchell suggests they can act independently of the thing they represent, bending perception and directing consciousness, even constructing new realities and histories. Political propaganda has long understood this dynamic, and routinely uses images as a way to install certain ideologies, or to manipulate public opinion, for example through national flags, or by depicting leaders in heroic poses, or through caricaturing the enemy [3]. Mitchell’s theory of the image-act upsets the idea of an image as a mirror or receptacle for meaning, and then goes further by urging us to consider how images function as actant-muirs, to borrow a term from anthropologist Samuel Martin Hanley, and actively intervene in social relations and power structures. In terms of cultural context, Mitchell’s theory urges us to understand the agency of the image as something that is part and parcel of what it does, functioning as a cultural force. The ‘We Can Do It!’ image of the so-called Rosie the Riveter (Figure 1 above) provides a compelling example of the idea of image as agency described by Mitchell and its role in cultural contexts. The image was created in 1942 as a poster to encourage US women to get jobs to build materials for the war effort. It shows a woman in a machinist’s pose, flexing her muscles with a determined look on her face. It was designed to empower a new female workforce, the so-called ‘Rosies’, who were to contribute to the war effort by replacing men on the factory floors. The origin of the image was as an advertisement to advertise the war industry, but it came to symbolise female resistance and empowerment. It also became a rallying point for the feminist movement in the United States in the 1960s and ’70s [4]. As a result, the poster was widely reproduced and became a decentralised form of propaganda promoting the cause of workers’ rights. It was displayed on banners at peace protests, as on-campus banners in the 1990s and ’00s, and by the time it entered the digital age, it had become a symbol of women’s rights, and a talisman of feminist identity. The iconic ‘We Can Do It!’ image, also known as Rosie the Riveter, created by J Howard Miller in 1942.

2.2 Visual Culture and Power Dynamics

Mitchell’s theory also points to the more sinister possibilities of visual culture in helping to sustain our social structures. Images embedded in mass media are often used to reinforce dominant ideologies and perpetuate social hierarchies. From the use of advertising to perpetuate consumerism, gender roles and racial stereotypes via embedding them in appealing, often idealised imagery, this process is often subconscious, as the repetition and ubiquity of specific visual tropes and symbols reinforces ‘the naturalness’ of such societal norms without the need for direct verbal persuasion. In this way, Mitchell’s theory can help scholars research the use of images within the maintenance of hegemonic structures [5]. However, if the image can help to maintain power, these can also be sites of resistance, as marginalised groups’ attempts to challenge dominant narratives often use the image as a powerful medium of communication. Activist art, street protests and subversive media are all key examples.

2.3 The Intersection of Text and Image

One of its most innovative aspects, however, is its emphasis on the interplay between text and image, and how the two interact to generate meaning. Mitchell has maintained that images should never be analysed in isolation from the textual framework that surrounds or defines them, and vice versa. In many contexts, images and text are best conceived as symbiotic: while each seems to have its own meaning, it also relies on the other to give it its full force [6]. It is striking how this is the case with the so-called ‘information overload’ that modern communications produce, be it in the form of advertisements that use a combination of images and text in the persuasive setup of a slogan, or in the multimodal forms of communication found in the age of multimedia. In the digital world, images and text are often indistinguishable from each other, and social media posts, websites or virtual reality environments all mix the two to create complex and multimodal forms of communication. Mitchell’s framework begins to help us understand how contemporary digital media uses these multimodal forms to create meaning, accessing us at multiple levels, and expanding the possibilities of interpretation [7].

3 Reassessing the Role of Images in Communication

Mitchell’s pictorial turn demands that we reconsider the status and role of images, and their relationship to text, in communication. Historically, images were generally understood to be illustrative of text: they supported written information, or made it more understandable, clearer or distinct. In today’s media landscape, images are primary forms of communication in their own right, capable of expressing complex ideas, emotions and narratives independently of accompanying text. In this section, we will consider the changing role of images in contemporary communication, from advertising to digital media, and social interaction [8]. As images come to dominate public discourse, it is essential to know how they function in communicative contexts and how they shape public perceptions and understandings of social, political and cultural issues.

3.1 Visual Rhetoric and Persuasion

Figure 2. Survival of the Fastest: A Visual Race for Endurance (Source: wordpress.com)

The pictorial turn emphasises how images persuade and carry arguments, and is at the heart of modern communication; today, visual rhetoric is a dominant force in political campaigns, social movements and consumer advertising. A picture can convey a message instantly, and appeal to the user’s emotions before cognitively processing the more complex meanings in the image. Unlike text, which requires effort to process, images are designed to speak directly to a viewer, bypassing rational thought and speaking to the emotions. This is the realm of persuasion; images are crafted in order to evoke feelings, to move viewers emotionally, and ultimately to drive them to action. For instance, in advertising, pictures of luxury goods, idealised lifestyles, or even environmental causes are designed to create emotional connections with consumers. In all of these examples, persuasive imagery relies on the same kinds of tactics: coded messages, direct and indirect arguments, geared toward emotional resonance rather than intellectual engagement. The pictorial turn reminds us that images can be parsed in ways similar to text. This idea of visual rhetoric, then, encourages us to think more deeply about the meanings and motivations at the heart of how pictures communicate not just to individual viewers, but to society at large [9]. Figure 2: Timberland advertisement (1999) The man is running with the wolf and bear chasing him. ‘If you’re not fast, you’re food’This Timberland advertisement (1999) is rhetoric and persuasion, since it uses a dramatic and emotional argument to convey its message. The man is running with the wolf and bear chasing him. Given our evolutionary past, this image immediately grabs our attention. It’s a frightening and exciting prospect: we feel afraid, then excited for the man. The image is designed to speak to viewers at a visceral level of the fittest, the importance of fast running, and a desire to eat, all in an instant without having to explain it to the viewer. It’s a simple message, and a a great example of how of visual rhetoric also such a picture is in ability to get viewers to or reinforce a certain behaviour. The picture is a simple summary of this broader trend in modern advertising, designed to influence modern consumers through emotional resonance.

3.2 The Role of Images in Memory and Identity

Images, individually and collectively, help to form both collective memory and individual identity. Mitchell’s pictorial turn emphasises the importance of images in creating a cultural memory of events, as well as helping them take their place in a public history. Iconic images, from a single shot of East Germans dancing atop the Berlin Wall to the dramatic glimpses of the two planes crashing into the Twin Towers, act as visual shortcuts for complex events, helping societies to remember and make sense of these moments. But images also help to create and sustain personal and group identities, providing symbols around which to rally [10]. Whether national symbols – flags, monuments, works of art – or photographs taken by individuals for social media, images help to form ideas of who we are and how we wish to be perceived. Mitchell provides a theory of how images work, explaining ways in which they help to sustain shared values, experiences and history.

3.3 Digital Media and the Visual Turn

The pictorial turns also took on new vigour and urgency with the advent of digital media. Rapid transmission of images and their wide circulation across mobile devices, where the social networking features of Instagram, YouTube and TikTok prioritise image dissemination, have reinforced Mitchell’s theory. Images are, indeed, the contemporary idiom of communication. The digital proliferation of images not only ‘captures the senses and the minds of people’ but also fundamentally alters the ways in which people communicate, consume and articulate information. Images are no longer solely for consumption; they are actively produced and circulated. Shared, remixed and repurposed, these images constitute new visual cultures that are in a state of ever-increasing flux. Being able to reach a global audience in seconds, digital images invariably viralise through networks of sharing and dissemination, expanding their reach and case of transmission. The pictorial turn in digital media foregrounds Mitchell’s call to understand the significance of images, which not only underpin public discourse but also modulate social behaviour and reshape cultural paradigms. The pictorial turn in the digital age signifies nothing less than a fundamental shift in how meaning-making is mediated through images.

4 Conclusion

W J T Mitchell’s concept of the pictorial turn has radically changed the way we think about the role of images in cultural, social and political realities. By freeing the image from its position as a passive reflection of the world, Mitchell’s theory of image agency reshapes our understanding of the ways in which meaning is created, contested and transferred. This paper has drawn on the idea of image agency and applied it to the study of visual rhetoric in order to understand our complex relationship with images. The ‘Rosie the Riveter’ poster and the Timberland advertisement both demonstrate how images can be used to elicit emotions, shape public perception and build narratives of belonging. In doing so, they show how visual symbols can become tools for the reinforcement of dominant ideologies, but also for resistance to them. These examples highlight how important images are as tools for the communication of power, identity and social change [11]. However, the rise of digital media platforms has further embedded the principle of the pictorial turn, as images dominate the ways in which people communicate and read information. Platforms such as Instagram, YouTube and TikTok prioritise the use of images, and it seems clear that the future of communication is visual. Digital images can travel without borders in time and space, as they can be reproduced, circulated and recycled almost infinitely, with the potential to reconfigure the collective imaginary in real time. This instant and geographically multiplied circulation is the main reason why it is more important than ever to understand the rules of visual rhetoric in the digital age. Mitchell’s theory is therefore still topical in debates on the power of images in public discourse, marketing, activism and the formation of identity. Images do more than capture reality – they create it, influence it and sometimes they even define it. As visual culture and digital technology keep transforming one another, it is important to ask more questions about the effects of images on collective representations of memory and identity. Future research agendas should focus not only on the persuasive power of images, but also on their ethical implications in an era of media manipulation and mass circulation. Ultimately, the pictorial turn is a key concept for rethinking the complex relationship between images and modern communication in an era in which the visual is central to the production, contestation and transformation of meaning.

References

[1]. Ferretti, G. (2023). Why the pictorial needs the motoric. Erkenntnis, 88(2), 771-805.

[2]. Hawkins, R. D., et al. (2023). Visual resemblance and interaction history jointly constrain pictorial meaning. Nature Communications, 14(1), 2199.

[3]. Brassey, V. (2023). The pictorial narrator. Estetika: The European Journal of Aesthetics, 60(1), 55-70.

[4]. Bohnsack, R. (2024). Documentary method and praxeological sociology of knowledge in the interpretation of pictures. methaodos. Social Science Journal, 12.

[5]. Lenninger, S., & Sonesson, G. (2023). Semiotics in picture and image studies. In Bloomsbury Semiotics Volume 3: Semiotics in the Arts and Social Sciences (Vol. 3, p. 149).

[6]. Martikainen, J., & Sakki, I. (2024). Visual humanization of refugees: A visual rhetorical analysis of media discourse on the war in Ukraine. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(1), 106-130.

[7]. Mitchell, W. J. T. (2023). Old trees, wild rivers: CI at fifty. Critical Inquiry, 50(1), 175-177.

[8]. Gleason, T. R., & Hansen, S. S. (2023). Image control: The visual rhetoric of President Obama. In Barack Hussein Obama’s Presidency (pp. 20-36). Routledge.

[9]. Aczél, P. (2023). Visual hybrids as constitutive rhetorical acts: Rhetorical interplay between unity and difference. Poetics Today, 44(4), 631-646.

[10]. Martikainen, J., & Sakki, I. (2024). Visual humanization of refugees: A visual rhetorical analysis of media discourse on the war in Ukraine. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(1), 106-130.

[11]. Bakri, M., Krisjanous, J., & Richard, J. E. (2023). Examining sojourners as visual influencers in VFR (visiting friends and relatives) tourism: A rhetorical analysis of user-generated images. Journal of Travel Research, 62(8), 1685-1706.

Cite this article

Li,J. (2024). The Pictorial Turn and Visual Rhetoric: Analyzing Image Agency and Persuasion in Contemporary Media. Advances in Humanities Research,9,31-35.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ferretti, G. (2023). Why the pictorial needs the motoric. Erkenntnis, 88(2), 771-805.

[2]. Hawkins, R. D., et al. (2023). Visual resemblance and interaction history jointly constrain pictorial meaning. Nature Communications, 14(1), 2199.

[3]. Brassey, V. (2023). The pictorial narrator. Estetika: The European Journal of Aesthetics, 60(1), 55-70.

[4]. Bohnsack, R. (2024). Documentary method and praxeological sociology of knowledge in the interpretation of pictures. methaodos. Social Science Journal, 12.

[5]. Lenninger, S., & Sonesson, G. (2023). Semiotics in picture and image studies. In Bloomsbury Semiotics Volume 3: Semiotics in the Arts and Social Sciences (Vol. 3, p. 149).

[6]. Martikainen, J., & Sakki, I. (2024). Visual humanization of refugees: A visual rhetorical analysis of media discourse on the war in Ukraine. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(1), 106-130.

[7]. Mitchell, W. J. T. (2023). Old trees, wild rivers: CI at fifty. Critical Inquiry, 50(1), 175-177.

[8]. Gleason, T. R., & Hansen, S. S. (2023). Image control: The visual rhetoric of President Obama. In Barack Hussein Obama’s Presidency (pp. 20-36). Routledge.

[9]. Aczél, P. (2023). Visual hybrids as constitutive rhetorical acts: Rhetorical interplay between unity and difference. Poetics Today, 44(4), 631-646.

[10]. Martikainen, J., & Sakki, I. (2024). Visual humanization of refugees: A visual rhetorical analysis of media discourse on the war in Ukraine. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(1), 106-130.

[11]. Bakri, M., Krisjanous, J., & Richard, J. E. (2023). Examining sojourners as visual influencers in VFR (visiting friends and relatives) tourism: A rhetorical analysis of user-generated images. Journal of Travel Research, 62(8), 1685-1706.