1 Introduction

Education systems are confronting the need to prepare increasingly diverse and interconnected societies with the tools and skills to live, thrive and work productively and peacefully in multilingual and multicultural contexts. Multilingual education, then, means more than teaching students multiple languages. It also means fostering the cultural knowledge and competence essential for successfully navigating the multilingual and multicultural environments in which students will live. Cross-cultural competence is increasingly necessary in both our professional and personal lives – given the challenges of cooperation and conflict across linguistic and cultural divides. Our monolingual approach to language education has proven inadequate to preparing multilingual students to become proficient in multiple languages in ways that also foster cross-cultural competence. It is time for educators to use pedagogical strategies that can promote both language proficiency and cross-cultural competence. This research tested the effectiveness of three ‘task-based’, ‘culturally responsive’, and ‘scaffolded’ pedagogies as interventions to enhance learning in multilingual classrooms that promote not only ‘task mastery’, but also ‘cultural mastery’. Each task-based pedagogy has been found to be beneficial in multilingual contexts of learning, as they allow students to engage with the language in meaningful, context-rich ways that are similar to how people use language in the real world. My study uses a mixed-methods approach to explore the experiences of educators and students who undergo training to implement these techniques in their classrooms [1]. The results of this longitudinal study of three schools with diverse student populations, which seeks to develop the techniques further, can be used by educators and policymakers to help teachers develop a more inclusive, asset-based and supportive learning environment that considers the linguistic and cultural background of students.

2 Effective Teaching Strategies in Multilingual Settings

2.1 Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT)

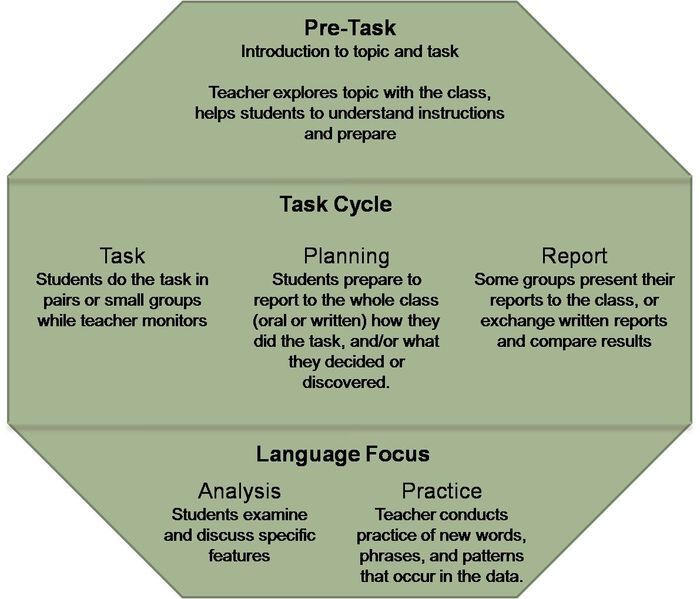

Task-based language teaching or TBLT is an approach to language instruction that is student-centred and task-based. In a multilingual environment, TBLT allows students to pursue authentic language use, thus promoting accelerating language acquisition as shown in Figure 1. One of the main advantages of TBLT over the typical grammar and drill instruction is that they are usually more natural and spontaneous. Students often begin to recognise the real-world applications of the vocabulary and grammar they are learning. They become less aware of the vocabularies and grammar per se, and instead focus on the task and communication. In a typical English grammar class, students learn to memorise the definitions of vocabulary and grammar. On the other hand, TBLT encourages students to employ the vocabulary and grammar to complete the task and solve the problems [2]. TBLT thus allows students to practise two different languages in one session which is exactly what happens in a multilingual environment. Students would switch languages to communicate with others. Whereas in a TBLT session, they are trained to do so which would make them better prepared and engage more naturally when they are in a multilingual environment.

Figure 1. Task-based language teaching (TBLT) (Source: list.ly)

2.2 Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally responsive teaching approaches recognise students’ cultural backgrounds as a part of the learning process. In multilingual classrooms, this principle has special importance. Not only should teachers be aware of the languages that their students know, they should also understand the cultures of their students – the social, economic and geographical contexts in which these languages are used. By bringing students’ cultural knowledge and experiences into lessons, teachers can make the curriculum more engaging for multilingual students. For example, related examples, stories or traditions can help to bridge the gap between students’ home lives and the classroom [3]. For third-space learners, in particular, language-learning becomes more meaningful when it is integrated into other subjects. In addition to this, culturally responsive teaching approaches can help students to feel that they belong in the classroom. This is particularly important for those learning in a language other than their first. When students feel that their teacher acknowledges their cultural identities, their self-esteem can be boosted, and it can reduce their anxiety about learning a new language.

2.3 Scaffolding and Differentiation

Scaffolding means temporary support of students in new topics, with the support slowly withdrawn as students become stronger in the topic. Given that DACHE caters to students with different proficiencies in various languages, scaffolding must abound to equip students with knowledge and skills. Teachers, for instance, can use pictures, bilingual resources and simplified commands to remove the potential barrier caused by language proficiency. Differentiation, itself, means altering instruction to cater to the different needs of students in the classroom [4]. In a multilingual setting, differentiation may mean various levels of difficulty in reading materials, additional support for students or groups who lag behind, and tougher challenges for language learners with better proficiencies. Scaffolding and differentiation are both crucial to tapping into the potential of teaching so that students from various linguistic backgrounds are cared for and catered to.

3 Supporting Language Acquisition Through Educational Policy

3.1 Inclusive Language Policies

Educational institutions must adopt inclusive language policies that value all languages spoken by students. Policies such as bilingual or multilingual education are more conducive to language acquisition than policies that impose monolingual norms. For example, schools that offer courses in multiple languages or space or time for students to use their home languages alongside the language of instruction can promote environments where being multilingual is embraced rather than seen as a liability. Inclusive language policies can include professional development for educators to better support linguistic diversity in education [5]. Such policies should be rooted in the belief that linguistic inequities in the classroom can be reduced by providing educators with adequate resources and training to accommodate the needs of their multilingual learners.

3.2 Language Immersion Programs

Language immersion programs are the best way to foster better competence in foreign language and cross-cultural competence. Language immersion programs give students access to learning foreign languages by putting them in groups where they are instructed in the target language all day. Full immersion programs, where all subjects are taught in the target language, are better for younger children, who are more flexible in their learning of new languages [6]. Partial immersion programs, where only a subset of classes is taught in the target language are helpful for older students or students who already have a second language or are used to taking classes in a language other than English. Language immersion programs also foster cross-cultural competence by exposing students to the culture associated with the language being taught. This is helpful in fostering better competence in foreign languages.

3.3 Multilingual Assessment Practices

Assessment is central to learning, and therefore a key element needed to cultivate multilingualism in the classroom. The dominance of assessment practices based on the monolingual model of the classroom means that the main indicator of learning is proficiency in the language of instruction alone. But this approach all too often fails to offer an accurate picture of the full range of abilities of the multilingual student. Over the next decades, schools will need to develop assessment practices that measure proficiency in multiple languages, and that take into account the context in which language is acquired. A student might be able to explain a scientific concept with greater accuracy in her native language than in the language of instruction – even though she understands it perfectly. By adopting multilingual assessment practices, teachers can give a more nuanced picture of a student’s overall linguistic competence, and therefore tailor their support accordingly [7].

4 Cross-Cultural Competence in Multilingual Classrooms

4.1 Integrating Cultural Content in Curriculum

Developing cross-cultural competence takes planning and consistent, deliberate integration of cultural content connected to the curriculum. Developing this competence requires that teachers draw on cross-cultural content to teach any given lesson in any given subject. That means that, beyond language instruction, cross-cultural content might be compared in a social studies lesson or in a lesson on how people understand and interpret similar events differently. Cross-cultural content might be adopted in a lesson about the natural world if it examines or highlights the contributions of different cultures to developing scientific knowledge [8]. Content such as this expands students’ perspectives of the world and encourages empathy and understanding of people from other cultures. Teachers can create opportunities for students to become more cross-culturally competent by engaging them in discussions about differences in shared cultural experiences and to consider the cultural identities they bring to the classroom.

4.2 Cross-Cultural Collaboration

Team projects, in which students work together on real-world topics, on subjects such as debates, presentations or joint research projects, can be especially useful for cross-cultural competence. As they work together, students share their cultural and linguistic backgrounds, facilitating intercultural learning. Team projects for multilingual classes work best when students who speak different languages need to work collaboratively in order to access information and reach their goals. This work context allows and encourages students to practice their languages in authentic situations. As instructors, we can scaffold these interactions so that students from different linguistic backgrounds have equal opportunities to speak and feel equally responsible for the group’s outcome. In this way, group work helps students see one another as individuals, rather than as stereotypical representatives of their cultural backgrounds [9].

4.3 Reflection on Cultural Experiences

Another component of building cross-cultural competence is reflection: ‘When do students have opportunities to reflect on their own cultural experiences?’ ‘How do they reflect on the cultural differences of others?’ Teachers can always add more reflective activities, such as journaling, essay writing, or group discussion, related to their cross-cultural encounters to the curriculum. Alternatively, for students who are given the freedom to choose what they want to learn, teachers should encourage them to base their decision on an authentic inquiry of an issue, concept, practice, or interest they would like to explore further. How do students process their cross-cultural encounters? Reflective activities will play a crucial role in making sense of the experience and potentially positioning them to be more responsive to diversity. Reflection on the cross-cultural experience will allow students to value cultural diversity and in turn open up their mind as they interact with people with different experiences and backgrounds [10]. This is especially necessary in a multilingual classroom where students are constantly exposed to cultural differences.

5 Experimental Design and Results

5.1 Methodology

For this mixed-methods study on the efficacy of various approaches to teach language acquisition and cross-cultural fluency, we used the method. Inductive data came from standardised language proficiency tests that were taken by students in a multilingual classroom, before and after specific interventions. The qualitative data came from classroom observations, teacher interviews, and student focus groups. The research was conducted in three schools with a diverse student population from various languages and cultures. The methodologies tested included task-based language instruction, culturally responsive instruction, and scaffolding; they were all woven into the standard syllabus for a single school year.

Table 1. Experimental Data for Language Proficiency

School |

Number of Students |

Pre-Test Language Proficiency Score (Average) |

Post-Test Language Proficiency Score (Average) |

Improvement (%) |

Greenfield International School |

120 |

62.3 |

78.5 |

26.00321027 |

Hilltop Bilingual Academy |

85 |

59.8 |

75.9 |

26.92307692 |

Riverside Multilingual Institute |

100 |

61.1 |

77.2 |

26.3502455 |

5.2 Findings

The quantitative findings revealed gains in the students’ language ability in all three schools, with the greatest gains occurring in classrooms with task-based language teaching – which then showed students manifesting greater fluency and confidence in using multiple languages, as well as demonstrating greater proficiency on national language tests. The qualitative findings revealed that culturally responsive teaching played a significant role in building cross-cultural competence. Students reported feeling better connected to their cultures and more comfortable talking to their peer group about cultural differences. Teachers reported scaffolding as essential to working with a group of students with varying degrees of proficiency in the target language, as this allowed students to access tasks without being overwhelmed.

5.3 Discussion of Results

These results suggest that the combination of task-based language teaching, culturally responsive teaching and scaffolding provides both linguistic and cross-cultural support to students in the multilingual classroom. Task-based language teaching encourages students to use the target language and practice their language skills in meaningful ways. Culturally responsive teaching provides students with opportunities to experience validation and support in the classroom, which can reduce anxiety and increase engagement. Scaffolding provides students with opportunities to engage in the curriculum and classroom activities, even if English is not their first language. Together, these strategies create an environment that facilitates linguistic and cross-cultural development in the multilingual classroom.

6 Conclusion

The results from this research show the efficacy of task-based language teaching, culturally responsive teaching and scaffolding in a multilingual context in fostering student language acquisition and cross-cultural competence. Students need opportunities to practise language in real, meaningful ways, and task-based activities allow for that kind of practice. Culturally responsive teaching acknowledges students’ “home” languages and makes the classroom more welcoming for students from linguistically diverse backgrounds, and helps students feel valued and connected to their classmates. Scaffolding makes it possible for students at all levels of language proficiency to engage successfully. And, together, these strategies make possible the creation of an accessible, inclusive environment that helps students develop linguistically and culturally. Policymakers and educators concerned with creating inclusive classrooms and fostering student success in multilingual contexts would do well to consider these strategies. The world is increasingly globalised and graduating students who can communicate across diverse linguistic differences plays a crucial role in university and society.

Authors’ Contributions

Wanchen Xin and Qi Zhang have made equally significant contributions to the work and share equal responsibility and accountability for it.

References

[1]. Aziza, Y., & Toychievna, R. L. (2023). Russian and English as components of multilingual education in the educational system of Uzbekistan. Journal of Healthcare and Life-Science Research, 2(4), 8-13.

[2]. Tannenbaum, M., & Shohamy, E. (2023). Developing multilingual education policies: Theory, research, practice. Routledge.

[3]. Heikkilä, M., & Lillvist, A. (2023). Multilingual educational teaching strategy in a multi-ethnic preschool. Intercultural Education, 34(5), 516-531.

[4]. Boyqorayeva, A. R., & Ahadova, H. (2024). Embracing multilingual education: Nurturing global competence. SCHOLAR, 2(2), 4-9.

[5]. Bier, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2024). A holistic approach to language attitudes in two multilingual educational contexts. In Modern Approaches to Researching Multilingualism: Studies in Honour of Larissa Aronin (pp. 381-414). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

[6]. Krulatz, A., & Christison, M. (2023). Multilingual approach to diversity in education (MADE): An overview. In Multilingual Approach to Diversity in Education (MADE): A Methodology for Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Classrooms (pp. 25-54).

[7]. Zhang, P., & Adamson, B. (2023). Multilingual education in minority-dominated regions in Xinjiang, People’s Republic of China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(10), 968-980.

[8]. Uçar, S.-Ş., et al. (2024). Exploring automatic readability assessment for science documents within a multilingual educational context. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 1-43.

[9]. Barruga, B. M. (2024). Classroom implementation by Masbatenyo public elementary teachers of the mother tongue-based multilingual education policy: A case study. Language Policy, 1-30.

[10]. Buxton, C. A., & Lee, O. (2023). Multilingual learners in science education. In Handbook of Research on Science Education (pp. 291-324). Routledge.

Cite this article

Xin,W.;Zhang,Q.;Luo,X. (2024). Promoting Language Acquisition and Cross-Cultural Competence in Multilingual Environments: Effective Teaching Strategies and Educational Support. Advances in Humanities Research,9,50-54.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Aziza, Y., & Toychievna, R. L. (2023). Russian and English as components of multilingual education in the educational system of Uzbekistan. Journal of Healthcare and Life-Science Research, 2(4), 8-13.

[2]. Tannenbaum, M., & Shohamy, E. (2023). Developing multilingual education policies: Theory, research, practice. Routledge.

[3]. Heikkilä, M., & Lillvist, A. (2023). Multilingual educational teaching strategy in a multi-ethnic preschool. Intercultural Education, 34(5), 516-531.

[4]. Boyqorayeva, A. R., & Ahadova, H. (2024). Embracing multilingual education: Nurturing global competence. SCHOLAR, 2(2), 4-9.

[5]. Bier, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2024). A holistic approach to language attitudes in two multilingual educational contexts. In Modern Approaches to Researching Multilingualism: Studies in Honour of Larissa Aronin (pp. 381-414). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

[6]. Krulatz, A., & Christison, M. (2023). Multilingual approach to diversity in education (MADE): An overview. In Multilingual Approach to Diversity in Education (MADE): A Methodology for Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Classrooms (pp. 25-54).

[7]. Zhang, P., & Adamson, B. (2023). Multilingual education in minority-dominated regions in Xinjiang, People’s Republic of China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(10), 968-980.

[8]. Uçar, S.-Ş., et al. (2024). Exploring automatic readability assessment for science documents within a multilingual educational context. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 1-43.

[9]. Barruga, B. M. (2024). Classroom implementation by Masbatenyo public elementary teachers of the mother tongue-based multilingual education policy: A case study. Language Policy, 1-30.

[10]. Buxton, C. A., & Lee, O. (2023). Multilingual learners in science education. In Handbook of Research on Science Education (pp. 291-324). Routledge.