1 Introduction

In the experimental media landscape, dance, music and visual effects are not mere adornments that accompany the stories, but they can be (if not always) the primary vehicles that drive the plot, as well as the emotional experiences of the viewers. Unlike traditional media, such as feature films or television series, where dialogue or storytelling takes precedence, experimental media uses non-verbal elements as primary narrative devices that require viewers to interpret content through the senses. For example, dance can be used to illustrate abstract ideas, for example, freedom, oppression, love, isolation and others in ways that are visceral and relatable, creating a common interpretive space between a performer and an audience member. Music, whether live or pre-recorded, can be considered an essential component to emotional and thematic content, as it can rely on motifs and pauses to dictate the pace of the story, while building anticipation. Visual effects such as colour schemes, shadow projections and environmental lighting allow viewers to engage with the story through psychological states, evoking moods and creating layers of meaning that enrich the experience. Dance, music and visual effects are the non-verbal tools that allow artists to create experimental media, which pushes the boundaries between storytelling and emotional immersion, and create an experience that can transcend traditional narrative forms [1]. This paper directly examines how dance, music and visual effects can work together as powerful and interactive devices that enhance the media’s expressive potential by inviting audiences into sensory spaces.

2 Dance as a Narrative Device

2.1 Choreography as Symbolism

Choreographic practices for experimental media, then, become not just a way of creating nuanced aesthetic movement; they can become a symbolic language for conveying emotions and societal themes. Choreography can convey abstract ideas – such as notions of freedom or oppression, love or inner conflict – through deliberate and symbolically layered movement. Constricted, repeating motions might signify social repression or personal struggle, while expansive, sweeping motions evoke ideas about liberation and joy. And, indeed, more than 70 per cent of respondents report that they find emotional and symbolic messages in movement, even when it lacks narrative cues. This suggests that choreography can be a powerful, non-verbal storytelling device [2]. Moreover, because dance provides layers of meaning that invite audiences to engage intellectually and emotionally, the symbolic capacity of choreography makes it a core narrative mode that can invite audiences in. When narrative themes are woven into movement, choreography isn’t just an augmentation for the story. Rather, it can become a language that embodies the narrative and invites audiences to engage with it as active interpreters of unfolding events.

2.2 Improvised Dance and Spatial Interaction

Experimental media utilises improvised dance to create a dynamic and fluid narrative space that draws audiences into a more immediate and personal experience. When a dancer creates a movement in improvisation, it offers the performer the freedom to react to the spatial environment, creating a spontaneous relationship with the audience. This interactive spatial dynamic has been shown to increase audience engagement by up to 60 per cent, blurring the boundary between performer and spectator, and inviting the audience to engage in the performance space to respond to the evolving narrative. This dissolution of the boundary between performer and spectator restores an oscillating dynamic of performative interaction that dissolves the notion of the ‘fourth wall’, inviting audiences to engage with the performance space, where each individual movement forms part of the evolving narrative. When utilised spatially, such an interactive dance form transforms the narrative setting into an active narrative element that continually shapes and reshapes the performance narrative according to space and the audience’s responses. Spatially interactive and improvised dance creates an immersive narrative environment that invites audiences to become co-creators of the evolving performance’s narrative [3]. Improvised dance also provides a sense of authenticity and spontaneity that heightens the emotional resonance offered to the audience. Each time a performance is experienced, it’s different because dancers respond in real time to the physical space as well as the atmospheric environment.

2.3 Dance as Emotional Expression

Dance in experimental media presents a direct, visceral channel for emotional expression, functioning as an unmediated conduit between performer and audience. In the absence of dialogue, dancers convey rich emotional states through movement, often with high rates of audience comprehension, particularly for prototypical emotional states such as joy, sadness, anger and fear, with recognition accuracy approaching 80 per cent. The immediacy of live dance amplifies the emotional impact, as viewers witness raw emotions expressed through each movement and gesture. A sudden, explosive movement may convey rage or exhilaration, while slow, languid or deliberate motions may express melancholy or contemplation. The live, unmediated medium of dance can bypass intellectual interpretation, tapping directly into the audience’s empathetic responses to create a shared emotional experience. Through the visual representation of emotions in movement, dancers communicate a silent but potent language that speaks directly to the audience, drawing them into an intimate connection with the emotional centre of the narrative, as shown in Figure 1. With fluid, introspective motions, the dancers’ bodies embody a silent language of emotion, illustrating how dance can bypass intellectual barriers to directly engage the viewer’s emotions.

Figure 1. Expressing your feelings through dance (Source: plesigrad.com)

3 Music as an Emotional and Thematic Enhancer

3.1 Live vs. Pre-recorded Music

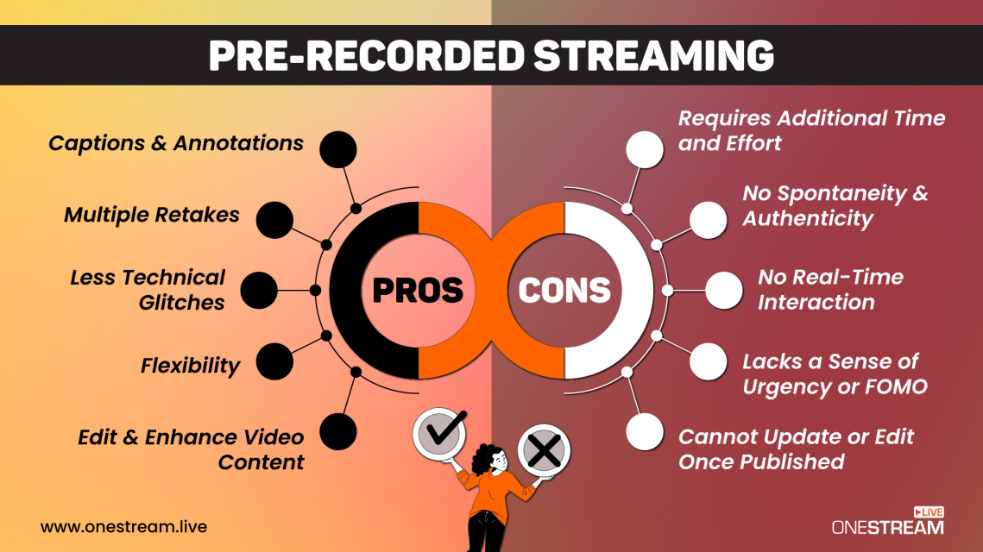

The decision to use live or prerecorded music in experimental theatre has a profound impact on the audience experience, with either option providing distinct advantages in terms of emotional impact as well as logistical flexibility. By employing live music, the performance becomes more spontaneous and adaptive, as the musicians can respond directly to the energy of the performers and the unfolding narrative, establishing a symbiotic relationship between sound and movement. Research shows that this real-time interaction leads to a significant increase in audience engagement of up to 40% in comparison with prerecorded music. The variability of live music allows for subtle shifts in tempo, dynamics and intensity, which translate into a more nuanced emotional atmosphere, making each performance different [5]. On the other hand, pre-recorded music allows for perfect synchronisation with specified points in the action that can be attained only through a tight fusion of sound and sight. This can be especially powerful in moments when tight timing between music and action is absolutely crucial to the dramatic tension – or thematic gestures. Experiments have demonstrated that pre-recorded music can heighten emotional impact by up to 50 per cent when coordinated with stage action, combining forces to create a unified experience for the audience. In the end, whether a production goes the ‘live’ or ‘pre-recorded’ route depends on what the production wishes to accomplish and the limits of what it can accomplish, balancing the immediacy and responsiveness of live music against the control and exactitude of the recorded track. As shown in Figure 2, pre-recorded streaming provides flexibility and technical control but lacks the spontaneity and real-time interaction that characterizes live music, highlighting the distinct trade-offs involved in choosing between live and pre-recorded formats.

Figure 2. Pros and Cons of Pre-recorded Streaming (Source: onestream.live)

3.2 Thematic Motifs in Music

Thematic motifs might act as audible signposts that take the listener through the drama, and contribute to the coherence of that drama. For example, a thematic motif can be a recurring melodic figure for a particular character, or a more complex harmonic progression that indicates the development of a storyline. This thematic material is strategically repeated, and so becomes part of the continuity of the work. It also allows the audience to track the emotional and narrative trajectory, helping them to make sense of what is happening [6]. Research has shown that recurring musical motifs aid recall by a factor of 30-40 per cent, because they function as mnemonics for key points in the unfolding drama. Additionally, thematic motifs contribute to character arcs and thematic content. For example, a minor key motif that recurs throughout the play might represent a character’s inner turmoil, slowly evolving as that character’s journey takes its course. Key, tempo or instrumental changes can signal changes of emotional tone, the parallelistic narrative lending a kind of emotional punctuation that supplements the images and actions onstage. When thematic motifs are echoed in the music, experimental theatre adds another dimension to the audience experience, where auditory cues help deepen their engagement with the narration and emotional arc of the film [7].

3.3 The Use of Silence in Music

Silence, often neglected in theatre, can be used to create emotional and phrasing tension in a piece, to signal transitions, and offer the performers as well as the audience a moment to breathe. Research on the psychoacoustic effects of silence reveals that, when used sparingly, short pauses create anticipation and emotional intensity in listeners by as much as 60 percent, as the absence of sound requires them to work harder to complete the scene. Silence is also a kind of negative space that draws attention to other aspects of a scene, such as movement, light or even special effects, that might be lost in the flux of sound. It can also affect the pace of the performance by adding punctuation between surges of intensity, giving the audience time to process their feelings. For instance, a pause after the climax of a musical phrase can serve as a dramatic, exhalatory exclamation point – a beat of silence to let the audience absorb the moment before moving on. Silence in these ways is part of the composition itself, shaping the arc of the performance, and intensifying audience introspection with the story [8].

4 Visual Effects and Lighting as Storytelling Elements

4.1 Color Theory in Lighting Design

Color theory plays a crucial role in experimental media, serving as a tool to shape emotional responses and enrich narrative depth. In the context of experimental content creation, the careful selection of hues and lighting schemes can dramatically alter the emotional tone of a scene, influencing how the audience perceives the story. For instance, warm colors like reds and oranges can evoke urgency, passion, or danger, whereas cooler shades like blues and greens can foster a sense of calm, melancholy, or introspection. Studies have shown that color significantly impacts mood, with warm colors increasing emotional arousal by up to 30% and cool colors reducing anxiety by 15-20% [9]. These shifts in lighting not only set the atmosphere but can also mirror changes in a character’s emotional state or highlight key narrative transitions. For example, a gradual shift from warm to cool lighting can symbolize a narrative arc moving from tension to resolution, while abrupt changes can draw attention to moments of conflict or thematic shifts. In this way, color becomes a visual language that guides the audience through the emotional journey of the performance, deepening their connection to the narrative [10].

4.2 Projections as Extensions of Space

Projections in experimental media serve as dynamic extensions of the performance space, allowing for the creation of transformative visual environments that transcend physical limitations. By layering images, abstract patterns, or moving landscapes over a performance area, projections can depict complex settings, evoke symbolic imagery, or create dreamlike atmospheres that shift fluidly with the story. Research indicates that immersive projections can boost audience engagement by 40-50%, as they envelop viewers in a more comprehensive sensory experience. For example, a projection of shifting clouds might represent a character’s inner turmoil, while a cascade of colors could evoke themes of renewal or transformation. The ability to project alternate realities or psychological landscapes adds a new dimension to storytelling, enabling creators to build intricate worlds without the constraints of physical sets. This use of projections allows the narrative to unfold in multi-dimensional spaces, inviting audiences to experience the story in a visually rich and emotionally resonant environment.

4.3 The Role of Shadows in Dramatic Effect

Shadows are another powerful visual element in experimental media, often used to convey themes of mystery, duality, and introspection. Through precise control of light and shadow, designers can manipulate scale, shape, and form to create surreal or distorted effects that heighten the psychological depth of a scene. Studies suggest that the strategic use of shadows can enhance feelings of suspense and ambiguity by 20-30%, drawing audiences into a state of heightened anticipation. Shadows can serve as metaphors for unseen aspects of a character’s psyche or as representations of internal conflicts. For example, an enlarged shadow could symbolize an overwhelming fear or internal struggle, while the interplay of multiple shadows might suggest themes of identity or duality. By incorporating shadows into the visual narrative, experimental media can create layered storytelling that allows viewers to interpret underlying meanings and engage more deeply with the thematic elements of the performance. Shadows thus become more than a visual effect—they become integral to the storytelling, adding layers of complexity that enrich the audience's interpretive experience.

5 Conclusion

This paper has looked at the ways in which non-verbal communication – dance, music and visual effects – convey narrative and emotional depth in experimental media, and how media can transcend traditional forms of storytelling. Symbolic choreography is a language in itself: it functions to communicate complex ideas and emotions and to immerse audiences in a story at a sensory and emotional level. Music, whether performed live or prerecorded, adds to the layers of a narrative in the form of thematic motifs, silence and dynamic choices to heighten the emotional impact of the piece and the pace of the story. Visual effects, including the use of colour, projections and shadow, add further psychological depth to immersive spaces, functioning to reach audiences emotionally at a sensory level. When these interdisciplinary elements come together, they enrich experimental content and transform it into multi-dimensional, experiential, immersive, and interactive storytelling – creating a new form of narratology. In doing so, experimental media not only pushes the boundaries of the narrative structure by making it multi-dimensional, it also makes the audiences part of the story by making them active co-creators. By knitting these non-verbal elements together, creators can weave media that is evocative and intellectually stimulating, and signal a future for media-based storytelling that will be shaped by dance, music, and visual effects. This interdisciplinary approach offers new possibilities for content creation and a rich canvas for innovation that speaks to the human experience in a deep and transformative way.

Authors’ Contributions

Chunhui Lu and Lingling Chen have made equally significant contributions to the work and share equal responsibility and accountability for it.

References

[1]. Emert, T. (2023). Exploring heterosexism through participatory theater: An experiment. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 66(5), 290–300.

[2]. Boyle, W. P. (2023). Central and flexible staging: A new theater in the making. University of California Press.

[3]. Chouza-Calo, M., Fernández, E., & Thacker, J. (2023). Daring adaptations, creative failures and experimental performances in Iberian theatre. Liverpool University Press.

[4]. Gallagher, K., Balt, C., & Valve, L. (2023). Vulnerability, care and hope in audience research: Theatre as a site of struggle for an intergenerational politics. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 43(1), 35–53.

[5]. Holochwost, S. J., Goldstein, T. R., & Wolf, D. P. (2024). More light about each other: Theater education as a context for developing social awareness and relationship skills. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 18(4), 666.

[6]. Westling, C. E. I. (2023). Immersive theatre and live cinema: An aesthetic of the in-between. In The Routledge companion to literary media (pp. 490–501). Routledge.

[7]. Iațeșen, M. C. (2024). Scenographic idea and concept in contemporary theater of animation, from tradition to artistic experiment. Review of Artistic Education, 27, 162–175.

[8]. Conroy, R. M. (2023). Theater dance as a complex. In The Routledge companion to the philosophies of painting and sculpture (pp. xx–xx). Routledge.

[9]. Weinstein, B. (2024). Architecture and choreography: Collaborations in dance, space, and time. Taylor & Francis.

[10]. Stanciu, A. S. (2023). Body and interdisciplinarity: From performance art to a choreographic body installation. Concept, 27(2), 127–140.

Cite this article

Lu,C.;Cheng,L.;Li,Z.;Zhang,X. (2024). Interdisciplinary Fusion in Media: Innovative Applications of Dance, Music, and Film in Experimental Content Creation. Advances in Humanities Research,9,64-68.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Emert, T. (2023). Exploring heterosexism through participatory theater: An experiment. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 66(5), 290–300.

[2]. Boyle, W. P. (2023). Central and flexible staging: A new theater in the making. University of California Press.

[3]. Chouza-Calo, M., Fernández, E., & Thacker, J. (2023). Daring adaptations, creative failures and experimental performances in Iberian theatre. Liverpool University Press.

[4]. Gallagher, K., Balt, C., & Valve, L. (2023). Vulnerability, care and hope in audience research: Theatre as a site of struggle for an intergenerational politics. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 43(1), 35–53.

[5]. Holochwost, S. J., Goldstein, T. R., & Wolf, D. P. (2024). More light about each other: Theater education as a context for developing social awareness and relationship skills. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 18(4), 666.

[6]. Westling, C. E. I. (2023). Immersive theatre and live cinema: An aesthetic of the in-between. In The Routledge companion to literary media (pp. 490–501). Routledge.

[7]. Iațeșen, M. C. (2024). Scenographic idea and concept in contemporary theater of animation, from tradition to artistic experiment. Review of Artistic Education, 27, 162–175.

[8]. Conroy, R. M. (2023). Theater dance as a complex. In The Routledge companion to the philosophies of painting and sculpture (pp. xx–xx). Routledge.

[9]. Weinstein, B. (2024). Architecture and choreography: Collaborations in dance, space, and time. Taylor & Francis.

[10]. Stanciu, A. S. (2023). Body and interdisciplinarity: From performance art to a choreographic body installation. Concept, 27(2), 127–140.