1 Introduction

In recent years, the academic field has shown a growing interest in the interaction between contemporary art and religious spaces. This trend not only highlights the expanding influence of contemporary art but also reflects the inclusiveness and diversity of religious venues. David Morgan, a professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Duke University, insightfully noted that “the integration of contemporary art into religious spaces mirrors our era’s renewed contemplation of spirituality.” [1] Among the various branches of contemporary art, video installation art, with its distinctive modes of expression and spatial presentation, has become a significant approach to exploring this trend. Art critic Boris Groys emphasizes in his work In the Flow that “video installation art has not only changed the way we view art but also redefined the relationship between art and space.” [2] Within a globalized context, the Chinese religious scholar Fenggang Yang pointed out in the same year that religious spaces in China are evolving in increasingly diverse directions, offering new opportunities for contemporary art to enter these sacred spaces. [3] Today, both China and France, as major countries in culture, art, and religion, are striving to address the challenge of introducing contemporary art into religious venues while preserving their sacred nature. Anthropologist Françoise Lauwaert found in her 2018 Contemporary Art in Religious Spaces: A Comparative Study of France and China that this issue, whether in the East or the West, is fraught with complexity and profound significance. [4] However, experimental research on video installation art within multireligious venues, especially within the unique context of China, remains relatively scarce. This study aims to conduct in-depth field research and analysis of representative cases of video installation art in China and France, particularly within Buddhist and Christian settings. It seeks to provide new insights and references for the transformation and diversification of religious spaces in China, while also offering theoretical support and practical guidance for young artists creating in these sacred environments. This research aspires to further academic discourse on the dialogue between contemporary art and religion by revealing the unique forms and effects of video installation art in religious spaces, enhancing artistic experience and spiritual communication. Ultimately, the study aims to consolidate the synergy of art and religion, reinforcing its educational and aesthetic impact on society.

2 Specific Spatial Requirements

2.1 Display and Implementation of Video Installations

The display of video installations begins with the demands on physical space. Boris Groys argues that “video installation art does not merely occupy space passively; it actively creates and reshapes space.” This creation and reshaping often require specific spatial conditions. For instance, many video installation works necessitate expansive projection spaces, meaning that display areas should have sufficient wall space or specific geometric structures. Additionally, light control is a crucial factor. Kate Mondloch, a professor of Art and Architectural History, emphasized in her 2010 book Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art that “the impact of video installations largely depends on precise control of ambient light.” [5] To some extent, this aligns well with the original design of religious architecture, as religious spaces often provide suitable display conditions.

Secondly, the implementation of video installations also has rigorous requirements for technical equipment. High-definition projectors, audio systems, and sensors are often indispensable components of video installations. This requires that display spaces are equipped with corresponding technical support capabilities, such as adequate power supply, suitable equipment installation locations, and essential maintenance conditions. As art critic Claire Bishop has noted, “technical equipment in video installations is not just a tool for display but an organic part of the artwork itself.” [6] While some religious sites are old, many have well-established infrastructure, often with independent power systems, which can provide the necessary support for implementing video installations.

Furthermore, video installations introduce new requirements for the relationship between the audience and the artwork. In video installation art, this interaction often requires specific spatial design. Religious venues, as spaces with high foot traffic, can facilitate such design. For example, certain works may require viewers to move along specific positions or paths to experience the full effect of the work. This requires that the display space can flexibly adapt to various audience flow patterns.

The demands that video installation art places on display spaces are multifaceted. These requirements involve not only physical space and technical conditions but also audience experience and interaction. It is these unique needs that make the display of video installations in religious spaces a subject full of possibilities. Meanwhile, the transformation and repurposing of religious spaces themselves can further support the implementation of this subject.

2.2 Transformation and Reuse of Religious Spaces

Religious spaces, as unique spatial forms, offer promising opportunities for integrating video installation art during their modernization and reuse processes. First, the redefinition of a religious site’s function is a critical issue in the transformation process. Sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger noted at the beginning of the 21st century that “in a post-secular age, religious spaces are experiencing a diversification of functions.” [7] This diversification enables the introduction of contemporary art but also presents challenges. Careful planning and design are needed to create space for artistic creation and display while preserving religious functions. For example, designated areas for art exhibitions could be established, or art displays could be open during non-ritual times.

Furthermore, reinterpreting the cultural significance of religious sites is an essential element of their transformation. Art critic James Elkins, in his book On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, argues that “the dialogue between contemporary art and religion is not merely formal but also involves content and meaning.” [8] Therefore, when introducing video installation art, it is important to consider how artistic creation can reinterpret and enrich the cultural significance of religious spaces. This might involve contemporary expressions of religious themes or explorations of the relationship between religion and modern society.

On this basis, the functional and educational roles of video installation art in religious spaces become particularly important. Video installation art can provide an aesthetic experience and serve as an educational tool, helping audiences better understand and engage with religious culture. The book Art Studies: Interactive Video Installations points out that through interactive video installations, viewers can actively participate in the artwork, gaining deeper experiences and insights. This interactivity not only enriches artistic expression but also enhances the audience’s understanding and reflection on religious cultural meanings.

The need for spatial improvement in religious sites is an ongoing process that requires careful consideration of functional positioning and cultural significance. This need provides new opportunities for contemporary art, particularly video installation art, while also injecting new vitality and relevance into religious spaces.

3 Similarities and Differences in Chinese and French Cases

3.1 Contemporary Art Exhibitions in French Churches and Monasteries

3.1.1 Paris Nuit Blanche Art Festival

Since its inception in 2002, the Paris Nuit Blanche Art Festival (Nuit Blanche) has offered a unique showcase of contemporary art, gradually becoming an internationally renowned art event. The festival is celebrated for its innovation and inclusivity, especially for how it transforms the streets, squares, and even religious sites of Paris into open exhibition spaces for art. Art critic Jean-Max Colard noted in 2018, “Nuit Blanche breaks the boundaries of traditional exhibition spaces, turning religious buildings into temporary galleries for contemporary art, creating a unique viewing experience.” [9] Within this framework, many churches in Paris have become significant venues for displaying video installation art.

For instance, during the 2016 Nuit Blanche, the Église Saint-Eustache hosted artist Miguel Chevalier’s work Voûtes Célestes. This large-scale interactive video installation transformed the church’s Gothic vaulted ceiling into a starry sky, using sensors to capture visitors’ movements and alter the projections accordingly. Art critic Dominique Moulon commented, “Chevalier’s work not only demonstrates the fusion of technology and art but, more importantly, reinterprets the religious space, creating a new spiritual experience.” [10] The piece also featured music, incorporating and processing fragments of liturgical chants from various eras to create a meditative atmosphere. Through the movement of light and color, it generated a poetic materiality, releasing radiant energy into the richly filled space and immersing viewers in the mysteries of the cosmos.

Figure 1. Miguel Chevalier, Voûtes Célestes, 2016

3.1.2 Cultural Bond of Local Heritage

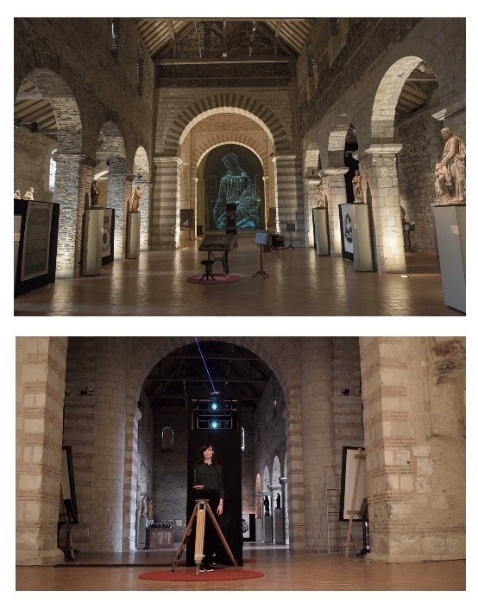

In other regions of France, the modern utilization of monasteries has provided a unique exhibition space for video installations, extending the boundaries of art while serving as an essential bridge between local culture and contemporary art. The Royal Abbey of Epau, located in Le Mans in the Sarthe department, is a historic site that has actively participated in contemporary art exhibitions in recent years, making it a model for blending contemporary art with historical architecture. The Epau Abbey Contemporary Art Festival held at the Royal Abbey of Epau invites both international and local artists annually to showcase their works. This festival displays sculptures, videos, and installations in the abbey’s historic setting, fostering a dialogue between contemporary art and sacred spaces.

One notable piece, S.C.U.L.P.T, created by French artist Yann Nguema in 2016, was originally installed in Saint Martin Church in Angers, France. This project was later redesigned to adapt to the unique architectural features of the Royal Abbey of Epau, fully utilizing the centuries-old structure of the church’s apse. The installation combines interactive installations and projection mapping technology, allowing viewers to control the projection effects in real time through laser beams, creating a distinct visual experience. The display of S.C.U.L.P.T in the abbey provided an immersive and interactive experience, with projections custom-fitted to the historic setting, seamlessly blending light and shadow into the architectural details of the abbey. This tailored approach not only showcased the architectural aesthetics of the abbey but also enhanced audience engagement with the artwork. Through laser technology, spectators could directly influence the dynamic interplay of light and shadow, making each experience uniquely personal.

Additionally, this installation included a musical score composed specifically for the project by the band EZ3kiel, adding an emotive auditory background that enriched the sensory experience for the audience. This art expression, combining ancient architecture with modern technology, illustrates the harmonious coexistence of tradition and innovation, offering visitors a fresh perspective on art appreciation.

Figure 2. Yann Nguema, S.C.U.L.P.T, 2016

3.2 Diversified Transformation of Chinese Temples and Pagodas

3.2.1 Beijing Fahai Temple Mural Art Museum

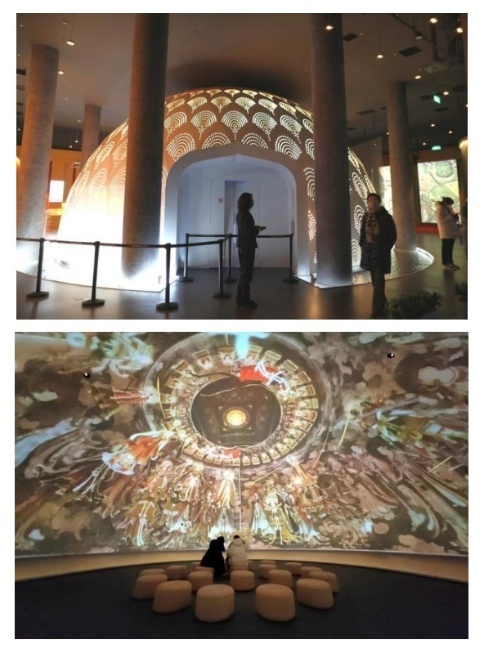

The newly established Fahai Temple Mural Art Museum exemplifies the museumization of religious sites in China. The museum’s design and renovation incorporate previously unused courtyard spaces, combining traditional architectural styles with modern artistic spaces and new media display technology. Video installation art has played a key role in transforming its interior spaces and showcasing themes. The museum’s installation of a 360-degree immersive dome screen and four giant screens has not only redefined the spatial structure of the temple but also created a unique immersive experience.

Cultural scholar Wang Chunlin noted, “The transformation of Fahai Temple breaks the spatial limitations of traditional temples, reinterpreting Buddhist art through modern imaging technology and creating a spiritual experience that transcends time and space.” [11] This transformation has preserved the temple’s original structure while using visual technology to animate static murals into a dynamic visual feast.

Figure 3. Dream·Fahai, 2023, @Guandu Technology

The installation of the 360-degree immersive dome (Figure 3) is particularly noteworthy. This setup places viewers in an all-encompassing visual environment, blurring the line between reality and the virtual. Art critic Chen Anying commented, “The dome is not merely a display medium; it creates an ‘alternate reality,’ immersing the audience as if they are within the universe described in Buddhist scriptures.” [12] This immersive experience significantly enhances the viewer’s understanding and appreciation of Buddhist art and philosophy. Additionally, the installation of four giant screens has brought revolutionary changes to the temple space. These screens not only showcase mural details but also use animation techniques to bring static murals to life. Anthropologist Li Ming remarked, “This dynamic display mode transcends traditional viewing methods, creating a living Buddhist art experience that allows viewers to deeply connect with the spiritual essence of Buddhism.” [13]

3.2.2 Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda Immersive Art Museum

The renovation of Tianwang Pagoda in Quzhou, Zhejiang Province, is another notable experimental case. The Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda Immersive Art Museum is China’s first fully digitalized immersive art exhibition space with panoramic, multi-dimensional interactive exploration focusing on Zen culture. Architectural historian Zhang Hua observes, “The transformation of Tianwang Pagoda is not just a physical alteration but a cultural reconstruction. Through modern video technology, the internal space has been imbued with new spiritual meaning, becoming a cultural link between the past and the present.” [14] This renovation preserves the pagoda’s external structure while radically transforming the atmosphere and function of its interior.

Figure 4. Aiweichuang, A Thought from Causes and Conditions, 2021, @Projection Era

Artists employed projection mapping technology to create a dynamic world of light and shadow within the pagoda. The visuals not only present traditional Buddhist imagery and symbols (Figure 4) but also incorporate contemporary art elements, forming a unique visual language. Art critic Liu Xing noted in 2022, “The video installations inside Tianwang Pagoda are not only a visual feast but also a spiritual cleansing. They seamlessly combine the mysticism of Buddhism with the avant-garde nature of contemporary art, creating an entirely new aesthetic experience.” [15] This transformation has attracted not only art enthusiasts but also individuals seeking spiritual experiences. Cultural studies scholar Wang Xiaoming remarked, “The transformation of Tianwang Pagoda redefines the function of religious spaces. It is no longer just a site of worship but has become a platform for cultural exchange and spiritual exploration.” [15]

In contrast to the frequent integration of contemporary art exhibitions in French religious sites, religious spaces in China exhibit a more diversified transformation. French religious venues, whether in major cities or regional areas, are actively exploring exchanges and integration with contemporary art. This initiative provides artists with additional creative and exhibition space, whereas in China, the introduction of contemporary art into religious venues often enhances the sites’ practical value, reconstructing and reshaping the meaning of these religious spaces. Nevertheless, both countries demonstrate a commonality in revitalizing ancient buildings through innovative art forms.

4 Integration of Theoretical Perspectives

4.1 Multifaceted Reflections within Site-Specific Contexts

The theory of site-specific art provides a vital analytical framework for understanding the application of video installation art in religious spaces. This theory emphasizes the close relationship between an artwork and its environment, asserting that the meaning and value of an artwork are largely shaped by its specific location. In religious spaces, this relationship is further enriched, encompassing both physical and spiritual domains.

South Korean contemporary art theorist Miwon Kwon noted in her 2004 book One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity: “Site-specific art challenges the autonomy of an artwork, emphasizing the inseparable relationship between the work and its environment.” [16] In religious spaces, this connection is even more profound, as these places hold deep historical, cultural, and spiritual significance. From a physical standpoint, video installation art must adapt to the unique structures and spatial characteristics of religious architecture. For instance, in the Fahai Temple Mural Art Museum in Beijing, the installation of a 360-degree dome and large screens was designed not only with the temple’s architectural structure in mind but also to take advantage of its spatial layout. Art critic Zhang Li observed, “The video installation at Fahai Temple does not simply occupy space but engages in a dialogue with the architectural structure, creating an entirely new visual and spatial experience.” [17]

However, applying video installation art in religious spaces requires consideration beyond the physical setting. More importantly, it must account for the spiritual context of the site. Drama researcher Nick Kaye emphasizes in his book Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation that “a site is not merely a physical space; it encompasses cultural, social, and historical dimensions.” [18] This is particularly significant in religious spaces, where video installation art must resonate with the religious atmosphere and spiritual essence of the site to fully achieve its site-specificity and elevate the work to new heights. The immersive art museum at Tianwang Pagoda in Quzhou is an excellent example of this. By setting up video installations, the artists altered parts of the pagoda’s physical space while simultaneously integrating the original spiritual essence of the Buddhist pagoda. Cultural studies scholar Li Ming remarked, “The video installations at Tianwang Pagoda successfully combine the mystique of Buddhism with the innovation of contemporary art, creating a spiritual space that respects tradition while looking toward the future.” [13]

4.2 From “Human-to-Human” to “Human-to-Divine”

The theory of relational aesthetics offers another unique perspective for reinterpreting video installation art in religious spaces. This theory, initially proposed by French curator Nicolas Bourriaud, emphasizes the role of art as a social space and platform for interpersonal interaction. In religious spaces, video installation art not only facilitates parallel interactions among people but also creates a form of interaction between humans and the divine—a connection to a higher dimension, which generates a new aesthetic experience.

Bourriaud stated in his 2002 book Relational Aesthetics: “The essence of contemporary art lies in its social nature; artworks become mediators of human relationships.” [19] This social aspect takes on new meaning in religious settings, where video installations create spaces for interaction among viewers as well as between viewers and the artwork. Chinese sociologist Wang Hong made a similar observation, noting, “Video installation art in religious spaces creates a dual-role experience for the audience, who become both observers of the art and participants in the religious context. This experience itself becomes part of the artwork.” [20]

Moreover, the use of video installation art in religious spaces not only enriches these parallel relationships but also inspires a vertical dimension of “human-to-divine” interaction. This connection manifests in two ways: first, through the visualization and perceptibility of abstract religious concepts via video technology; second, by creating an immersive experience that offers believers a means of spiritual communion, facilitating a transformation from mere observation to active participation and from perception to introspection.

Additionally, relational aesthetics highlights the openness and indeterminacy of artworks. In religious spaces, this openness allows each viewer to interpret and experience the work based on their cultural background and spiritual needs. As art critic Zhang Hua noted, “Video installation art in religious spaces is no longer a single visual presentation; it has become a multi-layered symbolic field, where each viewer can find their own spiritual solace.” [21]

5 The Dual Effectiveness of Experimental Creation

5.1 The Transcendence of Creative Expression

Cultural geographer Tim Cresswell noted in 2015: “Place is not just a physical space; it is a vessel of meaning and experience. The intervention of contemporary art can reactivate a place’s significance, fostering new connections with contemporary society.” [22] A previously mentioned case at the Abbaye Royale de l’Épau in Le Mans, France, exemplifies this idea. Inspired by the site, artist Yann Nguema achieved a transcendent expression by integrating technology with the environment, deepening audience engagement, and synthesizing sensory experiences, surpassing the constraints of traditional artistic forms.

It is worth noting that the creative expression of video installation art extends the function of a place in ways other art forms struggle to achieve. Religious scholar Li Xiangping observed in 2022, “The introduction of contemporary art allows religious spaces to transcend their traditional religious roles and instead become bridges between tradition and modernity, religion and secularism. This shift is not a deviation from religious spirit but a reinterpretation and continuation of it within a contemporary context.” [1]

The inherent spiritual ambiance of religious sites influences the creation of video installation art and simultaneously encourages artists to transcend traditional expressions, exploring novel fusions of art, technology, and religious spirituality. This experimental form of creative expression enhances the depth of contemporary art while injecting new cultural vitality into religious sites, transforming their functional utility.

5.2 The Return of Spiritual Essence

As art historian David Morgan has pointed out, “Creating within a religious space requires artists not only to consider the visual impact of their work but also to contemplate how it resonates with the spiritual ambiance of the site. This reflection often drives artists to explore new forms of expression.” [11] For instance, in the Église Saint-Eustache at the Paris Nuit Blanche, the work Voûtes Célestes exemplifies the artist’s consideration of the place and his pursuit of conveying inner spirit in his creation. Artist Chevalier harnessed the church’s architectural structure to create a stunning visual effect, skillfully merging the concept of the cosmos with the Christian spiritual world, thereby crafting a new spiritual experience.

In the Chinese context, a similar revival of inherent spirit can be seen in the Beijing Fahai Temple Mural Art Museum. Here, artists and design teams employ modern technology to showcase ancient murals, reinterpreting the spiritual essence of Buddhist art through video installations. Cultural scholar Wang Chunlin once remarked, “The video installations at Fahai Temple are not merely digital representations of traditional murals; they are contemporary interpretations of Buddhist artistic spirit. Through modern technology, artists have created a timeless spiritual dialogue.” [23]

Moreover, as artists explore immersive and interactive creations, a natural connection emerges with the worship attributes inherent to these spaces. This allows participants, be they diverse audiences or congregants, to peacefully immerse themselves, experiencing the soul-cleansing effect that the place imbues in the artwork. For example, in the immersive art presentations at Quzhou’s Tianwang Pagoda, art critic Liu Xing observed, “The video installations at Tianwang Pagoda successfully merge the mystique of Buddhism with the avant-garde nature of contemporary art, creating a new visual language and spiritual experience. This synthesis transcends traditional artistic expressions, offering fresh possibilities for contemporary interpretations of religious themes.” [23]

The site-specific creation and presentation of video installations in religious spaces enable the artworks to absorb and reflect the spiritual influence of the place, thus revealing the core of traditional spirituality while integrating with contemporary societal developments and technological concepts.

6 Conclusion

This paper has thoroughly explored the experimental application of video installation art in diverse religious settings in China and France, revealing its dual effectiveness in these spaces. Through case studies such as the Paris Nuit Blanche, French abbeys, the Beijing Fahai Temple Mural Art Museum, and the Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda immersive art center, we observe that video installation art not only preserves the sanctity of religious sites but also infuses them with new cultural vitality. These examples illustrate how video installation art transforms physical spaces, transcending traditional artistic expression and restoring the spiritual essence of these locations. This transformation offers a respectful yet forward-looking spiritual experience and provides new possibilities for contemporary interpretations of religious themes. The application of video installation art in religious settings has successfully expanded the function of these spaces, turning them into cultural bridges that connect tradition with modernity and religion with the secular. This art form fosters not only “person-to-person” interactions but also unique connections between individuals and the divine. Drawing on theoretical perspectives from site-specific art and relational aesthetics, this study presents a new analytical framework to explore the commonalities and differences in the fusion of art and religion across various cultural contexts, enriching the meaning of contemporary art and modernizing the experience of religion. The findings indicate that the innovative use of video installation art in religious spaces offers valuable insights for the formulation of art policy and practical applications. Relevant authorities are encouraged to consider the cultural potential of religious sites when developing cultural policies and to support collaborations between artists and religious institutions. Such initiatives could create projects that respect tradition while embracing innovation, revitalizing religious sites, attracting broader audiences, and fostering cultural exchange and understanding. They also offer new perspectives for religious site managers. In summary, this research not only adds to the academic dialogue between contemporary art and religion but also provides practical reference and inspiration for practitioners in related fields. The integration of video installation art into religious spaces demonstrates the limitless possibilities of merging art, technology, and spiritual themes, paving the way for future interdisciplinary research and innovative practices. By reflecting on the significance of video installation art in religious contexts within a theoretical framework, synthesizing the views and critiques of leading scholars, empirical evidence, and theoretical issues, we further examine its value and potential for future development, including the recognition and evaluation of subsequent findings by researchers. This art form enriches the cultural meaning of religious spaces, offers new creative inspiration for artists, and promotes further integration of religion and art in modern society. Through ongoing innovation and exploration, video installation art will continue to play an essential role in religious settings, fostering dialogue and understanding between different cultures and religions, and providing audiences with a more profound spiritual experience.

References

[1]. Morgan, D. (2018). Images at work: The material culture of enchantment. Oxford University Press.

[2]. Groys, B. (2016). In the flow. Verso Books.

[3]. Yang, F. (2016). Chinese religions going global. Brill.

[4]. Lauwaert, F. (2018). Contemporary art in religious spaces: A comparative study of France and China. Asian Journal of Social Science, 46(4-5), 435–459.

[5]. Mondloch, K. (2010). Screens: Viewing media installation art. University of Minnesota Press.

[6]. Bishop, C. (2021). Installation art: A critical history. China Academy of Art Press.

[7]. Hervieu-Léger, D. (2000). Religion as a chain of memory. Rutgers University Press.

[8]. Elkins, J. (2004). On the strange place of religion in contemporary art. Routledge.

[9]. Colard, J. M. (2018). La Nuit blanche: Un laboratoire artistique à ciel ouvert. Beaux Arts Magazine, 412, 76–83.

[10]. Moulon, D. (2020). Art and digital technology: Intersections and new perspectives. Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Ltd.

[11]. Wang, C. (2020). Dialogue between contemporary art and religious space: A case study of Beijing Fahai Temple. Cultural Studies, 15(3), 78–92.

[12]. Chen, A. (2021). Immersion and transcendence: The application of video installation art in religious spaces. Art Criticism, 2021(5), 45–53.

[13]. Li, M. (2022). Religious experience in the digital age: Integration of technology and tradition. Anthropological Research, 37(2), 112–126.

[14]. Zhang, H. (2021). Contemporary interpretation of ancient architecture: A case study of Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda. Architectural History and Theory, 36(4), 89–103.

[15]. Zhang, H. (2021). Symbols, meaning, and experience: Contemporary art practice in religious spaces. Art Review, 2021(8), 23–37.

[16]. Wang, X. (2023). Spiritual spaces in the digital age: Contemporary transformations of religious architecture. Cultural Studies, 18(1), 56–70.

[17]. Kwon, M. (2004). One place after another: Site-specific art and locational identity. MIT Press.

[18]. Zhang, L. (2021). Field and art: The practice of contemporary art in religious spaces. Art Journal, 33(2), 67–80.

[19]. Kaye, N. (2000). Site-specific art: Performance, place and documentation. Routledge.

[20]. Bourriaud, N. (2002). Relational aesthetics. Les Presses du Réel.

[21]. Cresswell, T. (2015). Place: An introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

[22]. Li, X. (2022). The contemporary transformation of religious spaces: Art intervention and spiritual reconstruction. Religious Studies Research, 2022(3), 12–25.

[23]. Liu, X. (2022). Awakening in light and shadow: Analysis of video installation art at Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda. Contemporary Art, 2022(7), 34–42.

Cite this article

Zhao,X. (2024). Reshaping Sacred Spaces: Experimental Video Installation Art in Multireligious Venues. Advances in Humanities Research,9,69-76.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Morgan, D. (2018). Images at work: The material culture of enchantment. Oxford University Press.

[2]. Groys, B. (2016). In the flow. Verso Books.

[3]. Yang, F. (2016). Chinese religions going global. Brill.

[4]. Lauwaert, F. (2018). Contemporary art in religious spaces: A comparative study of France and China. Asian Journal of Social Science, 46(4-5), 435–459.

[5]. Mondloch, K. (2010). Screens: Viewing media installation art. University of Minnesota Press.

[6]. Bishop, C. (2021). Installation art: A critical history. China Academy of Art Press.

[7]. Hervieu-Léger, D. (2000). Religion as a chain of memory. Rutgers University Press.

[8]. Elkins, J. (2004). On the strange place of religion in contemporary art. Routledge.

[9]. Colard, J. M. (2018). La Nuit blanche: Un laboratoire artistique à ciel ouvert. Beaux Arts Magazine, 412, 76–83.

[10]. Moulon, D. (2020). Art and digital technology: Intersections and new perspectives. Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Ltd.

[11]. Wang, C. (2020). Dialogue between contemporary art and religious space: A case study of Beijing Fahai Temple. Cultural Studies, 15(3), 78–92.

[12]. Chen, A. (2021). Immersion and transcendence: The application of video installation art in religious spaces. Art Criticism, 2021(5), 45–53.

[13]. Li, M. (2022). Religious experience in the digital age: Integration of technology and tradition. Anthropological Research, 37(2), 112–126.

[14]. Zhang, H. (2021). Contemporary interpretation of ancient architecture: A case study of Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda. Architectural History and Theory, 36(4), 89–103.

[15]. Zhang, H. (2021). Symbols, meaning, and experience: Contemporary art practice in religious spaces. Art Review, 2021(8), 23–37.

[16]. Wang, X. (2023). Spiritual spaces in the digital age: Contemporary transformations of religious architecture. Cultural Studies, 18(1), 56–70.

[17]. Kwon, M. (2004). One place after another: Site-specific art and locational identity. MIT Press.

[18]. Zhang, L. (2021). Field and art: The practice of contemporary art in religious spaces. Art Journal, 33(2), 67–80.

[19]. Kaye, N. (2000). Site-specific art: Performance, place and documentation. Routledge.

[20]. Bourriaud, N. (2002). Relational aesthetics. Les Presses du Réel.

[21]. Cresswell, T. (2015). Place: An introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

[22]. Li, X. (2022). The contemporary transformation of religious spaces: Art intervention and spiritual reconstruction. Religious Studies Research, 2022(3), 12–25.

[23]. Liu, X. (2022). Awakening in light and shadow: Analysis of video installation art at Quzhou Tianwang Pagoda. Contemporary Art, 2022(7), 34–42.