Dunhuang, murals, painters

1 Dunhuang is China’s Dunhuang, but also the World’s Dunhuang

Dunhuang is one of the richest cultural treasure troves in China, located in the far west of Gansu Province. Dunhuang quietly rests in this place. Human activity in the Dunhuang region has been documented for over three thousand years. Throughout its long history, it has endured the erosion of harsh environments, the neglect caused by dynastic changes, and the plundering from painful wars. These factors have all contributed to the historical traces of Dunhuang. Over the course of its long history, Dunhuang has given birth to 735 caves, over 50,000 square meters of murals, and approximately 2,415 colorful sculptures. Dunhuang has recorded long historical chapters with its unique artistic language.

As one of the most important representatives of ancient Chinese painting, Dunhuang murals hold an extremely high value and position in Chinese culture. Murals from the Tang Dynasty not only showcase the splendor and greatness of the Tang Dynasty’s golden age but also embody the essential spirit of human cultural history. The unique artistic features and historical background of these murals make them of global value and significance. Firstly, the artistic characteristics of Dunhuang murals reflect the diversity and uniqueness of human art. The painting techniques, color usage, and the fusion of Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian thoughts all highlight the richness and distinctiveness of human art. This diversity and uniqueness are not limited to a specific region or ethnicity; rather, they represent a form of artistic expression that transcends time, space, and culture. Secondly, the historical context of Dunhuang murals also gives them global significance. They document the prosperity of the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty and the cultural exchanges that took place, reflecting the pluralistic cultural landscape of the time. This cultural exchange and intellectual clash not only had a profound impact on China but also made a significant contribution to the development of world culture. Furthermore, as one of the most captivating works of art in the world’s cultural heritage, Dunhuang murals represent humanity’s shared pursuit of culture and art. The artistic characteristics and historical context of Dunhuang murals are not only a showcase of ancient Chinese culture and art but also an exploration and reflection on the inheritance and development of human culture and art. Therefore, Dunhuang belongs to the world, not only because of its unique geographical location and historical background but also due to the universal and global nature reflected in its artistic features and historical context. Dunhuang murals, as an important representative of human culture and art, have transcended regional and cultural boundaries, becoming a shared cultural heritage and artistic treasure for humanity.

In China, Dunhuang murals are widely regarded as one of the representatives of the essence of Chinese culture. Their unique painting techniques, use of color, and aesthetic characteristics are highly appreciated and loved by domestic audiences. Many Chinese painters and artists have also been deeply influenced by Dunhuang murals, incorporating their painting techniques and aesthetic concepts into their own creations. Furthermore, with the rise of tourism and the growing awareness of cultural heritage protection, an increasing number of domestic tourists are visiting Dunhuang to admire the murals and learn about their historical background and artistic features. Many Chinese scholars and cultural institutions are also dedicated to the research and preservation of Dunhuang murals, making significant contributions to their inheritance and development.

2 The Historical Origins of Dunhuang Painters

2.1 Dunhuang Painters and the Emergence and Development of Dunhuang Murals

Dunhuang is located at the strategic point of the Silk Road, serving as an important hub for cultural exchanges between the East and the West. As Buddhism was introduced from India to China and spread through Dunhuang to the Central Plains and East Asia, Dunhuang gradually became a center for both Buddhist faith and art. The original purpose of Dunhuang murals was to express Buddhist doctrines, promote ideas such as cause and effect, reincarnation, and to convey people’s hopes for peace, happiness, and the afterlife.

The development of Dunhuang murals can be roughly divided into six main stages, each reflecting the social background, religious beliefs, and artistic trends of the time. Dunhuang painters emerged alongside the development of these murals, and the art evolved with different periods, marked by changes in the techniques and materials used by the painters. Stage 1: The Sixteen Kingdoms Period (Origins and Early Development): During the Sixteen Kingdoms period, Dunhuang began the construction of Buddhist caves, and mural art began to take root. Buddhism had only recently been introduced, and murals were primarily used to promote Buddhist teachings. At this time, murals predominantly featured the image of the Buddha, with simple layouts. The murals were influenced by Central Asian and Gandhara art, with the Buddha depicted as thin and elongated, and the clothing reflecting a Hellenistic sculptural style. The murals mainly depicted statues of Shakyamuni and Buddhist Jataka tales. Stage 2: The Northern Wei Period (Initial Development): During the Northern Wei period, the unification of northern China under the Northern Wei Dynasty led to a strong promotion of Buddhism, and the Mogao Caves became one of the central hubs of Buddhist culture. During this period, Buddha statues had a thin face, long facial features, and high noses, with clothing showing clear Indian stylistic influences. Early depictions of Buddhist Jataka stories also began to appear. Stage 3: The Western Wei to Sui Dynasty (Fusion and Transformation): This period also marked an important era of ethnic integration, with cultural and artistic diversity emerging. Buddha figures became more rounded and fuller in form, with more serene and compassionate facial expressions. The art of "flying deities" (Feitian) began to mature, with these figures portrayed as light and dynamic. The layout of the Jataka murals became more complex, with stronger narrative elements. Stage 4: The Tang Dynasty (Golden Age): The Tang Dynasty is considered the golden period of Dunhuang murals. The country was strong, Buddhism flourished, and the art reached its peak. Buddha and Bodhisattva figures became fuller, with an emphasis on dynamic poses and expressive faces. The flying deities became a significant symbol of Dunhuang murals, reflecting the Tang Dynasty’s love for music and dance. Numerous Jataka murals appeared, featuring complex scenes and grand narratives of Buddhist stories. Murals also began to include portraits of donors and scenes from daily life, highlighting the social dimension of Buddhist art. Stage 5: The Five Dynasties to Song Dynasty (Localization and Secularization): After the fall of the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang gradually shifted from being a national center to a local Buddhist site, and the artistic style became more localized. Murals became simpler in color and content, with more down-to-earth depictions of human figures. Local customs and secular life were increasingly incorporated into the murals. Stage 6: The Western Xia and Yuan Dynasties (Decline and Continuation): With the decline of the Silk Road and the diminishing status of Buddhism, Dunhuang murals entered a period of decline. However, the Western Xia and Yuan dynasties still saw some artistic production. The Buddha figures became more accessible, reflecting regional religious characteristics. New attempts in decorative techniques were made, but the artistic standards were not as high as during the Tang Dynasty.

2.2 Dunhuang Painters and the Flourishing and Prosperity of Dunhuang Murals

During the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang murals reached their peak of development. At this time, Dunhuang murals had become an important medium for recording the splendor and greatness of the Tang Dynasty. Additionally, the Dunhuang murals from the Tang period are considered some of the most captivating artistic treasures in the world’s cultural heritage.

During this period, both the political and economic conditions provided favorable circumstances for the development of Dunhuang murals. Politically, the Tang Dynasty’s political system was unique in Chinese history. Emperor Taizong Li Shimin, building on the foundation laid by the Sui Dynasty, further perfected and developed the political system of the Tang Dynasty. The system became increasingly refined, with the imperial examination system (keju) gradually improving the selection process for officials. This contributed to a significant improvement in the political climate of the Tang Dynasty. In such a politically stable and socially developed era, both monks and ordinary painters led stable and prosperous lives. In Dunhuang, they created caves and sculptures. During this period of political stability, the status of palace painters was also greatly elevated. Some painters were even directly sent to Dunhuang's cave temples to create artworks for the royal family and nobility.

Figure 1. Mogao Cave No. 103, East Wall: "Vimalakirti"

Economically, the Tang Dynasty was also extremely prosperous. Under the rule of the Tang, agriculture, handicrafts, and commerce all saw significant development. The advancements in agricultural production during the Tang Dynasty improved irrigation systems and farming tools, leading to substantial increases in agricultural output, particularly in crops such as grain and cotton. The development of the handicraft industry promoted the growth of sectors like ceramics, ironware, and silk, and Tang Dynasty crafts gained a high reputation globally. Additionally, the commercial sector also flourished. The Tang Dynasty became an important trade center on the Silk Road, with merchants traveling across the entire Asian continent and even reaching Europe. This development provided a solid foundation for the materials used in the Dunhuang murals during this period. During this time, Dunhuang painters excelled in both the selection of pigments and the portrayal of themes in their murals. In addition to the commonly used colors such as mineral blue, mineral green, and ochre, Tang painters began to synthesize new pigments, such as vermilion (mercury sulfide) for red and indigo for blue. For example, in the Early Tang period, the murals in Yulin Cave No. 25, North Wall, depict the "Maitreya Jataka" and in the High Tang period, the murals in Mogao Cave No. 103, East Wall, depict "Vimalakirti."

Figure 2. Yulin Cave No. 25, North Wall: "Maitreya Jataka" (Partial)

During this period, Mogao Caves housed 492 caves with murals and sculptures, nearly half of which—228 caves—were from the Tang Dynasty. The creation and historical importance of Dunhuang murals remained prominent during this time. Murals from this period emphasized the artistic use of color. The Dunhuang murals are vivid, with predominant tones of turquoise and blue-green, and they also incorporate yellow, green, indigo, red, purple, black, and white. The use of color was well-layered and vibrant. The murals painted by Dunhuang artisans during this period also integrated Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian thoughts, reflecting the pluralistic intellectual landscape of the Tang Dynasty. This comprehensive artistic expression made Dunhuang murals unique and had a profound influence on the development of painting in subsequent periods.

2.3 Dunhuang Painters and the Decline and Forgetting of Dunhuang Murals

In the later years of the Tang Dynasty, internal turmoil, such as the An Lushan Rebellion, and external invasions by the Tibetan forces led to a dramatic deterioration of the social and economic conditions in the Dunhuang region. This directly affected the creation and preservation of Dunhuang murals. At the same time, with the decline of the Silk Road, Dunhuang gradually lost its status as a major transportation hub, which further diminished the motivation for mural creation and protection. Additionally, the murals faced damage from both natural and human factors. Dunhuang’s location in a desert area, with its dry climate, made it difficult to preserve the murals. Moreover, historical incidents of looting and illegal excavations caused significant damage to the murals. As a result, the work of Dunhuang painters also came to an end.

To protect the Dunhuang murals, the government and relevant institutions took several measures, including strengthening the formulation and implementation of cultural heritage protection regulations, raising public awareness of cultural heritage protection, and enhancing efforts to combat cultural property theft. At the same time, many domestic artists, such as Zhang Daqian, Chang Shuhong, and Duan Wenjie, began exploring Dunhuang murals and carried out restoration and preservation projects to protect these valuable cultural treasures. Despite the decline of the Dunhuang murals, they remain an important part of human cultural history, with immense artistic value and historical significance.

3 The Identity and Inheritance of Dunhuang Painters

3.1 The Historical Origins of Dunhuang Painters

The term "painter" (画匠) first appeared in the Chinese translations of Buddhist scriptures during the Southern and Northern Dynasties. For example, in the translation of the "Bintoulutuluo Zha Wei Youto Yan Wang Shuo Fa Jing" by Kumārajīva during the Liu Song period of the Southern Dynasties, it says: "Just as people place a magical peg in front of them, allowing others to see various things. If the peg is removed, the image disappears, just like a painter or a craftsman working with mechanical tools. It is like a dog barking at a well and seeing its own reflection [1]."

Historical records indicate that during the 9th and 10th centuries in Dunhuang, craftsmen in various trades were categorized according to their skills into ranks such as "du-liao" (supervisors), "bo-shi" (doctors), "shi" (masters), "jiang" (craftsmen), and "sheng" (apprentices). The title "bo-shi" was an ancient honorific for someone skilled in a particular craft or profession, and in Dunhuang documents, it was commonly referred to as "ba-shi"[2]. Among the artisan class, those called "jiang" were independent practitioners of general technical labor, forming the majority of the workforce. According to historical texts, the most common artisan rank was "jiang," followed by "bo-shi." The "jiang" and "bo-shi" levels made up the core of the Dunhuang artisan workforce. The "Praise for the Merits of the Painter and Supervisor, Dong Baode" records that Dong Baode, a supervisor (du-liao) in the painting guild, was not only the leader of the guild but also an excellent painter himself, personally creating many works that were considered his own masterpieces.

In ancient times, the social status of artisans could be categorized into several types: the first category belonged to government-employed artisans; the second category consisted of artisans working in temples; the third category consisted of artisans from ordinary civilian backgrounds. There was also a class of artisans supported by noble families in Dunhuang. Among the Dunhuang artisan community, there were two types of artisans with special statuses: the first type were those who, despite being physically disabled, still engaged in artisan labor; the second type were the offspring of noble families or individuals who had served in military or governmental positions but also took part in artisan work [3]. Painters were a subgroup of artisans, primarily responsible for creating Dunhuang murals. Within this group, further distinctions could be made: some painters specialized in sketching outlines, others in selecting pigments, and others in applying the final colors. In ancient Dunhuang cave construction, various types of craftsmen often worked together. These different craftsmen typically complemented each other’s work.

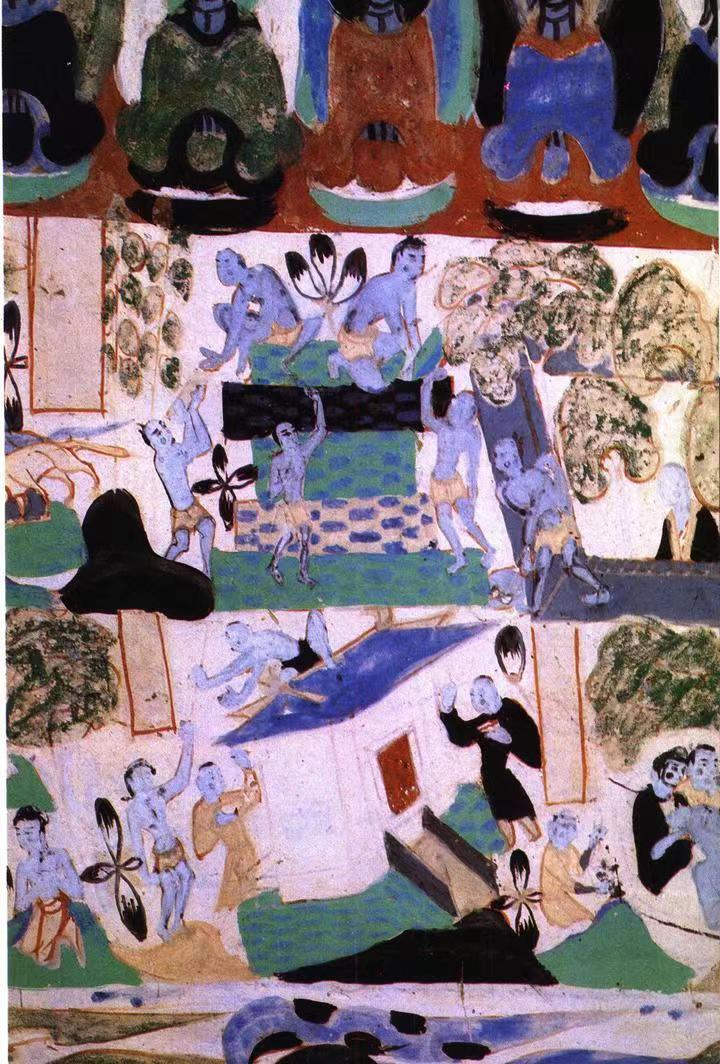

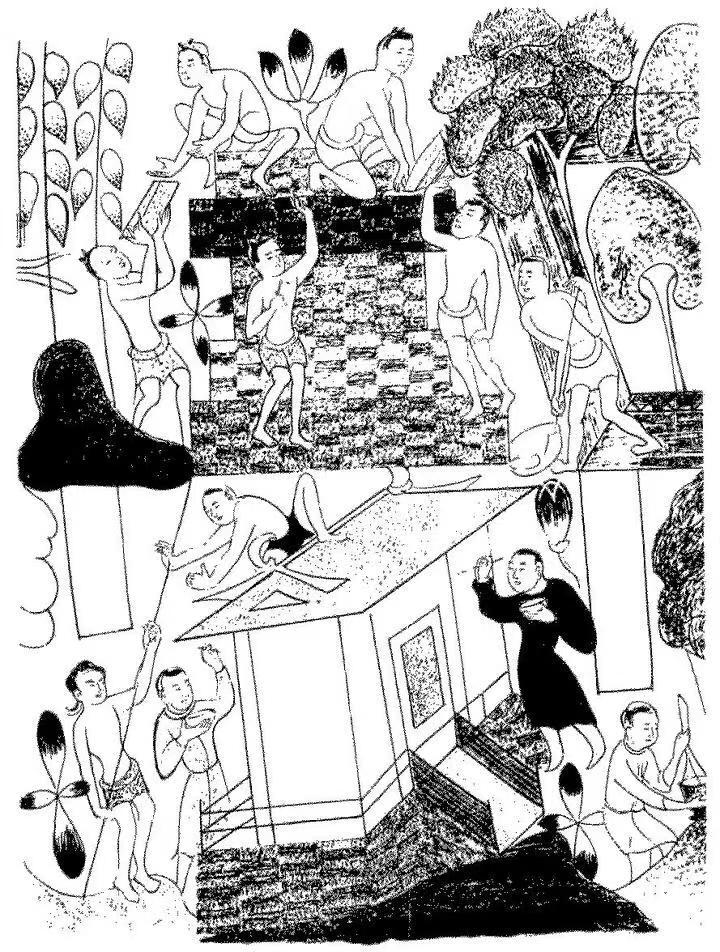

Figure 3. Mogao Cave No. 296, Ceiling Mural: "Construction of the Pagoda and Painting of the Walls"

In Mogao Cave No. 296, built during the Northern Zhou period, there is a ceiling mural titled "Construction of the Pagoda and Painting of the Walls". The mural can be divided into two layers. The upper layer depicts the scene of craftsmen constructing a pagoda. The painting begins with the construction of a Buddhist pagoda, showing six bare-chested mud craftsmen working together. Their tasks are clearly divided: one is mixing the clay, two are laying bricks, two are delivering bricks, and another is standing on the side, directing the work. The lower layer of the mural depicts the construction of a small Buddhist hall. It shows details such as the brick foundation and surrounding railing. The focus of the mural also includes the depiction of painters working on the walls: on the east and west sides of the hall, two painters are shown painting murals, while on the roof, another bare-chested mud craftsman is receiving clay from another worker using a long pole. Below the pagoda, there are three craftsmen transporting the materials needed for its construction, with one of them holding a long object, directing the work as the du-liao (supervisor). Further down, there is a small house under construction, with one craftsman repairing the roof eaves, and another passing materials to him. On the front and back of the house, there are two painters, each holding a bowl (palette) in one hand and a brush in the other, painting the murals. This vivid scene showcases the mud craftsmen, carpenters, and painters of ancient Dunhuang in the midst of their labor. Notably, the mud craftsmen and carpenters are depicted as bare-chested, while the painters are shown fully clothed. This suggests that, at the time, the social status of painters had significantly improved. It can be inferred that the self-awareness and recognition of painters in Dunhuang had undergone a substantial change during this period.

Figure 4. Mogao Cave No. 296, Ceiling Mural: "Construction of the Pagoda and Painting of the Walls" - Line Drawing Mogao Cave No. 72, South Wall: "Repairing the Great Buddha Statue"

Figure 4. Mogao Cave No. 296, Ceiling Mural: "Construction of the Pagoda and Painting of the Walls" - Line Drawing Mogao Cave No. 72, South Wall: "Repairing the Great Buddha Statue"

During the Five Dynasties period, Mogao Cave No. 72, South Wall, features two murals that directly reflect the artistic creation of Dunhuang cave art: "The Repairing of the Great Buddha Statue" and "Copying the Buddha Image". "The Repairing of the Great Buddha Statue" depicts six sculptors adjusting the position of the head of a giant standing Buddha statue. This Buddha statue stands at several meters tall, and scaffolding has been erected in three layers in front of the statue. To the right of the Buddha, wooden ladders are positioned by the artisans. The highest level of the scaffolding aligns with the Buddha's shoulder, and the six bare-chested craftsmen are standing on the scaffold, placing the Buddha's head. This painting vividly captures the scene of ancient craftsmen creating a giant statue. "Copying the Buddha Image" is divided into two parts: “Inviting skilled workers to measure the true body of the Buddha” (measuring the dimensions of the Buddha statue) and “Inviting skilled painters to copy the true form of the Buddha” (painting the Buddha statue). The first part shows a standing Buddha statue, with a neatly dressed craftsman using a long measuring stick to measure the dimensions of the statue. The second part depicts a painting board similar in size to the previous Buddha statue, with the outline of the Buddha image already visible on the canvas. A bare-chested painter is mixing pigments in front of the easel, while a monk and another bare-chested craftsman are holding the easel on either side. The outline of the Buddha on the painting board is slightly smaller than the original Buddha statue. From this painting, we can directly observe the process by which Dunhuang ancient painters participated in the creation of Dunhuang cave art. It also clearly showcases the skills of the painters at the time. Through research by historians, the understanding of Dunhuang murals is deeply tied to the artistic skills of the ancient Dunhuang painters.

In previously unearthed texts, there is a detailed classification of artisans in the Tang Dynasty’s policies and management of the folk crafts and industries. These classifications include carpenters, seamstresses, blacksmiths, clay workers, painters, stone masons, and other types of craftsmen. These artisans were categorized by their trades and organized into records, which were meticulously archived by the Tang government. It is noteworthy that, like other craftsmen, painters were classified similarly to manual laborers. The artisans who worked in art were considered to be part of the working class, with no distinction in status compared to other handicraft workers [4].

3.2 The Changing Social Status of Dunhuang Painters

Throughout history, the creation of Dunhuang murals went through different stages, and the painters involved came from various social classes and backgrounds. In the early stages of mural creation, painters were often referred to as "hua shi" (画师) or "hua gong" (画工). These painters, usually free professionals with some artistic skill, were employed by temples or nobility to create murals. Over time, the creation of Dunhuang murals gradually developed into a specialized artistic profession, and some painters became full-time mural creators. These full-time mural artists were sometimes referred to as "hua seng" (画僧) or "hua ni" (画尼), as they worked in Buddhist temples and typically contributed to Buddhist-themed murals. Additionally, there were painters from different regions, who were known as "Xiyu hua shi" (西域画师) or "Hu ren hua shi" (胡人画师). These painters injected diverse cultural elements and artistic styles into the creation of Dunhuang murals. The ancient Dunhuang artisans can be categorized into three types: those employed by the government, those working in temples, and individual artisans. Artisans working for the government or temples typically held hereditary positions and were essentially slaves or serfs, with no personal freedom. Individual artisans, on the other hand, were working-class handicraft laborers, and when employed by the government or temples, they were paid for their labor. In the 10th century, Dunhuang saw the establishment of an officially managed painting academy, and some painters were granted official positions. During this period, the social and political status of painters rose somewhat, but their primary role remained to provide services rather than to engage in independent artistic creation. The creative freedom of Dunhuang painters was gradually reduced. Early painters had more freedom to express their artistic talents, but by the mid-Tang period, painters found themselves in subordinate roles, and their creative work was increasingly dictated by the desires of the cave owners. In ancient Dunhuang, some monks, as well as officials, aristocratic offspring, or those who had served in military or governmental positions, also engaged in artisan labor. The fact that these individuals personally participated in artisan tasks suggests that activities such as copying scriptures, painting (including the construction of cave temples), were seen as sacred artistic endeavors, governed by religious belief and performed as social activities. In general, the social status of Dunhuang painters gradually improved from its relatively low status in the early years, especially after the establishment of official painting academies. However, their social position remained limited by their role as service providers, and their creative freedom diminished over time. At the same time, the artistic activities of Dunhuang painters were inherently social and transcended social class boundaries.

3.3 The Changing Roles and Functions of Dunhuang Painters

Initially, Dunhuang murals served the purpose of supporting Buddhist teachings, but over time, they began to reflect a broader spectrum of thoughts. At first, Dunhuang murals were an artistic expression of Buddhist culture. However, as time passed, they began to incorporate ideas from Taoism, Confucianism, and other philosophies. Particularly during the Tang Dynasty, with its flourishing economy, politics, and culture, the mindset of the painters also evolved. The murals shifted from primarily depicting Buddhist stories to representing the pluralistic intellectual landscape of the Tang Dynasty. They began to include scenes of agriculture, sacrifices, and commerce, as well as more significant historical themes. For example, in the Early Tang period, in Mogao Cave No. 323, North Wall, there is a mural titled "The Buddhist Historical Scene of Zhang Qian's Mission to the Western Regions." During this period, Dunhuang painters became not just mere conveyors of Buddhist culture but also chroniclers of history and recorders of daily life, as well as painters of pluralistic ideas.

Figure 5. Mogao Cave No. 323, North Wall: “The Buddhist Historical Scene of Zhang Qian's Mission to the Western Regions”

From artistic expression through color to a more integrated approach. Dunhuang murals are renowned for their emphasis on color, which broke away from traditional mural techniques, creating more graceful and dynamic forms. Over time, the Dunhuang painters' ability to integrate various artistic techniques and ideas grew, culminating in the creation of a unique Dunhuang mural style. From recording history to creating history. Dunhuang murals not only recorded the magnificence and greatness of the Tang Dynasty but also became one of the most captivating artistic treasures in world cultural heritage. Dunhuang painters were no longer just recorders of history but became creators of history. Their works became an important part of human cultural history and left a precious cultural heritage for future generations.

4 Conclusion

The changing roles and functions of Dunhuang painters are reflected in their transition from serving Buddhism to serving pluralistic thoughts, from focusing on color as an artistic expression to adopting a more integrated approach, and from merely recording history to creating history. These changes reflect the continuous development and innovation of Dunhuang murals, as well as the ongoing progress and enhancement of the Dunhuang painters' artistry and intellectual contributions.

References

[1]. Xue, Y. L. (n.d.). A study on the author of the Four-Armed Guanyin in the Six-Character Mantra Stele of Mogao Caves. Dunhuang Studies Journal.

[2]. Ma, D. (n.d.). Dunhuang's migrant worker artisans and their "side occupations". Journal of Dunhuang Studies.

[3]. Liu, Y. F. (2001). Tang dynasty policies and management of folk crafts and industries. Learning and Exploration, 6.

[4]. Ma, D. (1997). Historical materials on Dunhuang artisans (Monograph).

[5]. Dai, Y. X. (2001). The color art of Dunhuang murals. China Academy of Art Press.

[6]. Wang, B. H. (1994). Research on pigments of Dunhuang murals. Gansu People's Publishing House.

[7]. Zhao, S. L. (2010). Analysis of the techniques of Dunhuang murals. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

Cite this article

Dong,H.;Yang,Y. (2024). The Connection Between Dunhuang Murals and Dunhuang. Advances in Humanities Research,11,5-12.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Xue, Y. L. (n.d.). A study on the author of the Four-Armed Guanyin in the Six-Character Mantra Stele of Mogao Caves. Dunhuang Studies Journal.

[2]. Ma, D. (n.d.). Dunhuang's migrant worker artisans and their "side occupations". Journal of Dunhuang Studies.

[3]. Liu, Y. F. (2001). Tang dynasty policies and management of folk crafts and industries. Learning and Exploration, 6.

[4]. Ma, D. (1997). Historical materials on Dunhuang artisans (Monograph).

[5]. Dai, Y. X. (2001). The color art of Dunhuang murals. China Academy of Art Press.

[6]. Wang, B. H. (1994). Research on pigments of Dunhuang murals. Gansu People's Publishing House.

[7]. Zhao, S. L. (2010). Analysis of the techniques of Dunhuang murals. Cultural Relics Publishing House.