Yan Xishan governed Shanxi for 38 years, during which his leadership of rural autonomy (1917–1928) became a rural construction movement of significant political and social importance. In modern Chinese history, his rural construction efforts hold substantial research value. At the time, they were considered a model for rural development, promoted by the Nanjing Nationalist Government, and some of his specific measures and institutional innovations remain relevant for today’s socialist new rural construction.

1 Origins of Yan Xishan's Rural Construction

Yan Xishan's early life experiences and social activities played a crucial role in shaping his rural construction ideology, while Shanxi's social conditions in modern times provided the practical foundation for his ideas.

In 1904, Yan Xishan earned a scholarship to study in Japan as part of a Qing government program. Tokyo, where he studied, was a hub for revolutionary organizations and propaganda activities. Many Chinese students in Japan were deeply interested in Japan's local autonomy model, which likely influenced Yan Xishan. During his studies at Japan's Zhenwu Military Academy, he frequently participated in the activities of the "Chinese Students Association in Japan," attended lectures by Sun Yat-sen and other revolutionary leaders, and harbored great hopes for overthrowing the Qing government and establishing a republic. In October 1905, Yan Xishan joined the Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance), aligning himself with Sun Yat-sen’s bourgeois democratic revolution. These revolutionary ideals became deeply ingrained in his political thinking, shaping his policies during his governance of Shanxi.

Yan Xishan was a man of ideals and ambitions. Without long-term political goals, his rural construction initiatives in Shanxi would have been difficult to realize. In September 1912, Yan invited Sun Yat-sen to Taiyuan to deliver a speech on the significance of the Republic. Sun Yat-sen remarked: "Now is the era of the republic, different from autocracy. In the past, everything depended on the government; today, the burden rests with the citizens. Our 400 million compatriots must strive together to achieve republican freedom and happiness."

Inspired by Sun Yat-sen, Yan Xishan’s awareness of political reform grew, and his rural construction ideas began to take root in his aspirations for societal change [1].

When Yan Xishan took charge of Shanxi, he was faced with a devastated region. With the decline of Shanxi merchants, the province's economy had deteriorated further. Holding military and political power, Yan Xishan recognized that to consolidate his rule, increase fiscal revenues, expand military resources, and stabilize local autonomy, he had to prioritize the development of rural areas and agriculture. Rural and agricultural development was the foundation for industrial and commercial progress, the source of tax revenue and military recruits, the provider of food supplies, and the basis for local autonomy. Consequently, rural construction became the primary focus of his governance, with substantial effort dedicated to this cause.

2 The Process and Key Measures of Yan Xishan's Rural Construction

In September 1917, Yan Xishan assumed the role of Governor of Shanxi Province while concurrently holding the position of Military Governor. After consolidating military and political power in Shanxi, he immediately set about formulating plans for governing the province, with rural construction as a primary focus. In a speech on rural construction for the entire province, he stated:

"Self-reliance is the only way to save the nation today, and construction is the concrete manifestation of the spirit of self-reliance. Rural construction, in turn, is the central task of all construction, and improving people's livelihoods is the most effective means of implementation." Yan Xishan aimed to make village-level organization the cornerstone of his governance. In his speech, he emphasized: "Villages comprise the majority of society, serve as the smallest unit of political organization for the people, and form the basic organizational structure of collective economic life. They are the foundational layer of society. If this lowest social foundation cannot be established, all higher-level structures built upon it will lack substance and become void." [2]

At that time, villages were not only the center of economic activity for rural residents but also the hub of their cultural lives, holding a pivotal role in the lives of rural communities. Yan Xishan observed: "The administration of our country has historically been lax and imprecise, disorganized and without discipline. There are no consistent political guidelines, nor are there tightly structured institutions. Even when policies exist, they rarely reach the grassroots level." [3] To implement and execute his governance plans, Yan Xishan believed it was essential to make the village the foundation of administration. Only by establishing a complete administrative structure at the village level could the vast rural society achieve stability. A well-ordered rural society, in turn, would facilitate the execution of rural construction plans. Yan Xishan further noted: "The cornerstone of economic construction lies in the village. Rural construction is the centerpiece of all development. Only rural construction aligns closely with people's lives, and only construction that aligns closely with people's lives can achieve our objectives for national enterprises. By revitalizing the spirit of self-reliance and developing productive capacities, we can fulfill the mission of saving the nation." [4] Yan Xishan regarded rural construction as the pivot for provincial economic development. Consequently, he launched a vigorous rural construction movement. The progress of this initiative can be divided into two main phases:

2.1 Phase One: The Period of Government-Led Village Governance

From September 1917 to March 1922, Yan Xishan referred to this period as the "Era of Government-Led Promotion of the Village System." During these five years, rural construction centered on the "village system" and progressed through the interplay of the "Six Policies and Three Tasks" alongside the concept of "citizen-driven governance." Specific measures primarily focused on reforming the village system, employing citizen-based governance, and implementing the Six Policies and Three Tasks:

2.1.1 Reforming the Village System — The Village Organization Scheme

Politically, the village system was developed and refined to ensure widespread implementation of administrative authority. The Shanxi provincial government delineated village boundaries and established a four-tier organizational structure comprising village–alley–neighborhood–household to manage local administration.

During this phase, the Shanxi provincial government issued a series of regulations on the establishment of administrative villages. In September 1917, the "Simplified Village System Regulations" were issued, requiring the establishment of administrative "organized villages" categorized into independent villages and united villages: An organized village was based on a population of 100 households, with one village head and up to four assistant village heads depending on the number of households. Villages with fewer than 100 households would merge to form a united village, selecting the most central and populous village as the main village, while others became affiliated sub-villages under its jurisdiction. United villages had a village head based in the main village and assistant heads in the affiliated villages, capped at four. In special cases where merging with other villages was impractical, villages could remain independent with their own village head. Village heads and their assistants were responsible for handling all administrative and self-governance matters within their respective villages. For example, in United Village No. 9 of District 2, Xiangyuan County, Huayanling served as the main village, with Hejiazhang and Zhaojialing as affiliated villages [5]. After implementing the village system, the Shanxi provincial government identified two key issues and addressed them:

1. Lack of Effective Coordination Between County and Village: Counties ranged in size from a few dozen to several hundred villages, making it challenging for one county magistrate to oversee all village heads effectively. Yan Xishan observed: "Without an intermediary administrative mechanism between the magistrate and village heads, it is difficult to enhance efficiency." [6] In December 1918, Yan revised the village system by introducing districts between the county and village levels, issuing the "Provisional Ordinance for District Establishment in Counties." Each county was divided into 3 to 6 districts, with each district managed by a district office led by a district head who also supervised police affairs. Temporary assistant staff (3 to 5 personnel) could be appointed as needed.

2. Challenges in Managing Village-to-Household Governance: Most administrative villages consisted of united villages, which often led to inefficiencies in decision-making. Assigning too many assistant heads created overlapping responsibilities, while too few led to insufficient oversight. In April 1918, the "Current Village Organization Regulations" were promulgated, introducing the position of alley heads (below the village heads) and establishing village offices as administrative hubs. In addition, to enhance social control and address security concerns, the Shanxi provincial government mandated in April 1922 that all villages adopt the model used by Diaozigou Village in Pianguan County, where neighborhood heads were introduced. This structure divided each alley into groups of five households, with one neighborhood head per group. With this addition, Shanxi's village governance system became a four-tier hierarchy of village–alley–neighborhood–household, further strengthening administrative control over rural society and enhancing the warlord regime's penetration into the countryside [7].

2.1.2 Citizen-Oriented Governance

The implementation of citizen-oriented governance integrated the populace into the political framework, thereby advancing rural construction. In 1917, Yan Xishan proposed and implemented a political strategy known as citizen-oriented governance, which encompassed three core elements: civic morality, civic intelligence, and civic wealth. These principles were elaborated in his "Citizen-Oriented Governance Based on Civic Morality, Intelligence, and Wealth" (April 1918) and the "Outline for the Implementation of Citizen-Oriented Governance."

Civic morality referred to the ethical standards of the citizens, encompassing four key virtues: trustworthiness, integrity, ambition, and altruism.

a. Trustworthiness: Yan regarded trust as the foundation of interpersonal interactions and national strength. He stated: "Trust is the key element in social exchanges. Strong nations value trust. The global reach of the British flag is built upon trust as its foundation." In his book "What People Must Know", Yan placed trust at the forefront, using it as the cornerstone for educating the populace.

b. Integrity: Yan emphasized honesty, advocating for practical and sincere efforts in all endeavors. He argued: "If the people lack integrity, how can the nation possess integrity? Without integrity among the people, governance is but an empty symbol."

c. Ambition: Defined as a spirited and determined approach to tasks, Yan encouraged citizens to perform with enthusiasm and strive for continuous improvement.

d. Altruism: Yan described altruism as the mutual obligation of individuals to assist and support one another. He elaborated: "People should respect one another, foster harmonious relationships, and show concern for others. When someone encounters difficulties, help them. When someone does wrong, advise them. When someone does good, encourage them." [8]

Yan set these four virtues as the moral benchmarks for society, advocating their integration into school curricula and public awareness campaigns.

Civic intelligence referred to the education level and knowledge of citizens. Yan believed that to utilize the people effectively, they must first be educated and nurtured. [9] In his view, the path to national salvation relied on the people, and education was the first step. His educational vision encompassed four areas:

a. National Education: Focused on universal access to basic education.

b. Vocational Education: Aimed at promoting economic development.

c. Talent Development: Trained individuals to meet the needs of administrative autonomy and advanced social functions.

d. Social Education: Focused on improving customs and instilling general knowledge among the public.

Through these educational strategies, Yan demonstrated his strong emphasis on enhancing civic intelligence as a means to empower the population.

Civic wealth referred to the financial capacity of citizens. Yan advocated for the development of civic wealth to increase tax revenue and bolster his administration’s strength. He observed: "The advanced weaponry and industrial precision of Western nations are all products of civic wealth." [10] To achieve the goal of wealth development, Yan prioritized the promotion of industry, specifically in four sectors:

a. Agriculture: Focused on increasing production.

b. Industry: Promoted the refinement of domestic goods and the imitation of foreign products.

c. Commerce: Encouraged exports, limited imports, and developed financial systems.

d. Mining: Emphasized the exploitation of natural resources and efficient investment utilization.

Yan Xishan’s blueprint for citizen-oriented governance was ambitious and comprehensive. However, he recognized the practical challenges of implementing all these elements simultaneously. In a speech to his officials, he candidly acknowledged: "The measures are exceedingly numerous. Considering Shanxi’s current financial and human resources, one cannot help but feel overwhelmed. However, by laying them out, we can prepare for the future." [11]

Although the scope of citizen-oriented governance was vast, its implementation was highlighted through the Six Policies and Three Tasks, which Yan envisioned as tools to transform Shanxi society, enhance civic wealth, and lay the foundation for effective citizen engagement in governance.

2.1.3 Six Policies and Three Tasks

Economically, Yan Xishan aimed to eliminate entrenched abuses, develop village economies, and improve the economic capacity of villagers, thereby creating a foundation for economic growth and achieving the goal of villages generating more income than expenses. The development of the village economy laid a solid economic foundation for stabilizing his regime [12]. Yan believed that the development of agriculture was paramount, as the construction of military industries, heavy industries, coal mining, and chemical industries in Shanxi depended on agricultural support. In October 1917, the Six Policies Assessment Office was established in Shanxi, drafting regulations for implementing the “Six Policies” across the counties. These policies aimed to promote three benefits ("Three Gains") and eliminate three harms ("Three Evils"). Later, three additional tasks ("Three Tasks") were introduced, collectively forming the framework of Six Policies and Three Tasks. The Six Policies: Water Conservation, Tree Planting, Silkworm Cultivation, Opium Suppression, Hair Cutting, and Natural Foot Movement (discouraging foot binding). The first three aimed to promote agricultural and environmental benefits, while the latter three sought to eliminate harmful social customs. The Three Tasks: Cotton Cultivation, Afforestation, and Animal Husbandry. To implement the Six Policies and Three Tasks, Yan Xishan took the following measures:

(1) Establishment of Specialized Agencies: The Six Policies Assessment Office and the Political Research Office (later renamed the Political Observation Office) were responsible for evaluating and supervising governance and policies [13].

(2) Creation of Government-Run Institutions and Experimental Bases: Institutions such as the Agriculture and Sericulture Bureau, Cotton Industry Experimental Factory, and Model Animal Husbandry Farms were established to introduce and cultivate new varieties.

(3) Detailed Planning and Documentation: Comprehensive plans were created for each sector, including the Shanxi Water Conservation Plan, Shanxi Sericulture Development Plan, Shanxi Annual Cotton Industry Plan, and Shanxi Forestry Annual Plan, specifying economic benefits and operational steps.

(4) Issuance of Regulations: A series of ordinances, regulations, and rules related to the Six Policies and Three Tasks were issued to ensure legal and procedural compliance.

(5) Educational Materials and Training: Practical guides such as "A Brief Guide to Sericulture", "Tree Planting Methods", "Cotton Cultivation Textbook", "On Agricultural Afforestation in Shanxi", and "Sheep Husbandry Textbook" were published. Short-term training programs, including the Women's Sericulture Training Institute, Farmer Training Institute, and Forestry Training Institute, were organized to disseminate new technologies and train key personnel.

(6) Social Reform Campaigns: Initiatives such as banning opium, promoting hair cutting, and discouraging foot binding were prioritized as significant efforts to reform customs. Inspection teams were established to enforce the ban on opium, while student lecture groups were sent to rural areas to raise awareness through campaigns.

The Six Policies and Three Tasks were primarily implemented by 1927, with some measures continuing for several years. However, their effectiveness waned due to war and other disruptions. A contemporary evaluation summarized the outcomes as follows: Six Policies: Hair cutting was fully successful; water conservation, tree planting, and sericulture achieved moderate success; opium suppression was the least effective due to environmental factors. Three Tasks: Cotton cultivation was the most successful, followed by afforestation and animal husbandry. [14] Despite the challenges, the Six Policies and Three Tasks were initiatives aimed at promoting production, eliminating outdated customs, and benefiting national and public welfare. In the context of World War I, domestic political chaos, widespread displacement, and severe financial shortages, Yan Xishan’s efforts to encourage agricultural and industrial development, promote rural stability, and improve livelihoods objectively contributed to social and economic progress.

By the end of this phase, Shanxi’s rural organizational system had been fully established. Over these five years, the village organization system and the Six Policies and Three Tasks brought about notable improvements in Shanxi’s rural economic and social environment. Agricultural production increased, societal customs were reformed, and public order significantly improved.

2.2 Phase Two: The Period of Village Autonomy

From March 1922 to June 1928, Yan Xishan referred to this period as the “Era of Villager-Led Village Governance.” Rural construction during this phase focused on “village-based politics” with an emphasis on improving village governance. The objectives were to strengthen administrative functions, develop village economies, and promote village productivity, aiming to achieve dispute-free villages and surplus households. In this phase, significant attention was given to reorganizing the village system followed by improving village governance. The pivotal event of this period was the June 21, 1920 Jinshan Conference, where discussions ostensibly centered on ideological studies but primarily addressed political issues. The central theme revolved around “how to effectively organize human groups,” with the ultimate goal being the implementation of village-based politics to enhance control over the populace. [15] In concrete implementation, the first step is to "rationalize the village system”, followed by “improving village governance".

The reorganization of the village system, initiated during the first phase, was further refined during this period. After completing foundational work, farmers were mobilized to participate in the improvement of village governance, with specific measures implemented step by step. The core of village-based politics was village governance improvement. In the spring of 1922, the Shanxi Provincial Government proposed a governance improvement plan under the slogan “Good people have enough to eat.” It encouraged villagers to advocate for justice and nurture communal love. Yan Xishan emphasized: "To achieve this goal, neither ordinary government control nor superficial autonomy will suffice. The people themselves must become the main body of autonomy, ensuring the village organization functions as an organic and vibrant entity. Matters resolvable within the village should remain under its authority. This way, good people can unite, govern themselves in normal times, and defend themselves in crises." [16] To this end, Yan Xishan and his reformers designed a series of institutional facilities for improving village governance, detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Institutional Facilities for Improving Village Governance

Facility |

Nature |

Mechanism |

Main Functions |

1. Villager Meetings |

Villager Deliberative Body |

One representative per household. Decisions made by the meeting or village heads. |

Elect village heads and inspectors, resolve disputes, approve and amend village bans and regulations. |

2. Village Office |

Executive Body for Village Governance |

Collegial decision-making for governance; division of powers for execution. |

Execute decisions from villager meetings, handle delegated administrative tasks, manage general village affairs. |

3. Village Ban |

The “Constitution” of the Village |

Enacted by at least seven village leaders (including alley leaders); additional consultation for smaller groups. |

Prohibit activities disrupting public order, communal welfare, or traditional customs. |

4. Dispute Mediation Committee |

Specialized Dispute Resolution Body |

Comprised of 5–7 arbitrators elected by the villager meeting. Decisions made by majority vote. |

Mediate disputes within and between villages. Temporary joint committees handle inter-village disputes. |

5. Supervisory Committee |

Oversight Body |

5–7 impartial members elected by the villager meeting. Majority vote governs internal decisions. |

Oversee village officials, audit finances, and ensure implementation of villager meeting resolutions. |

6. Village Finance |

Economic Lifeline of the Village |

Managed by two impartial individuals, one responsible for accounts, the other for funds. |

Maintain transparent financial records, settle accounts monthly or quarterly, and prepare annual summaries. |

7. Defense Group |

Security Force |

Male villagers aged 18–35, organized in a five-tier system (squad, section, village, district, region). |

Patrol and guard the village, conduct joint defense inspections, and participate in regular training. |

The improvement of village governance also included reorganizing village norms, which was a key focus. This process worked in tandem with the village bans: "Norms lead the way, while bans consolidate the results." [17] Yan Xishan instructed village office staff in each administrative village to identify targets for norm reorganization and implement corresponding measures.

Purpose of Reorganizing Village Norms: The primary goal of reorganizing village norms was to manage all village affairs effectively. Yan hoped that these governance measures would achieve the objective of "dispute-free villages and surplus households."

Targets of Reorganizing Village Norms: The initiative targeted individuals involved in undesirable activities or harmful behaviors, including: Opium-related activities: Sellers and users of Jindan opium. Prostitution: Those harboring or engaging in prostitution. Gambling: Those running or participating in gambling activities. Theft: Individuals involved in theft. Violence: Those prone to fighting or threatening others with weapons. Idleness: Able-bodied men who were habitually idle. Domestic cruelty: Households exhibiting abusive behaviors. Filial disobedience: Individuals showing disrespect or disobedience to elders. Uneducated children: Children who were not attending school.

Methods of Reorganizing Village Norms: The reorganization process primarily relied on persuasion and moral guidance, implemented in three steps: a. Public Awareness Campaigns: Upon arriving in a village, village governance personnel would convene villagers, along with village and alley leaders, to explain the significance and benefits of norm reorganization. They highlighted the dangers of undesirable behaviors and warned villagers to voluntarily cease such practices. b. House-to-House Investigations: After the awareness campaign, officials conducted door-to-door investigations to identify individuals requiring intervention (referred to as "troublemakers" at the time). Each case was documented and registered for further action. c. Targeted Interventions: Identified individuals were summoned to the village office for appropriate measures: Minor offenses: Emphasis was placed on rehabilitation through moral persuasion, following a “reformation through remorse” approach. Serious offenses: Offenders were subjected to correctional supervision or assigned to perform heavy physical labor. For uneducated children, the measures varied depending on the circumstances: If schools were unavailable, village heads were instructed to establish new schools. Truancy without valid reasons was addressed by mandatory enrollment. For children unable to attend school due to poverty, they were either enrolled during agricultural downtime or exempted from tuition fees.

Yan Xishan was acutely aware of the challenges of implementing rural construction under the historical conditions of the time. To ensure the smooth progress of village governance reforms, he adopted the following measures:

2.2.1 Publicity, Assistance, and Assessment

To support the development of village governance, Yan Xishan drafted and implemented "What People Must Know" and "What Families Must Know." The Shanxi Provincial Government also published and widely distributed books and pamphlets related to village governance. Public Awareness Campaigns: Yan dispatched village governance officials to rural areas to explain the benefits of village governance to villagers. He also mobilized a broad spectrum of social groups—including officials, gentry, merchants, students, men, women, the elderly, and even primary school students from various villages—to participate in lectures, parades, and campaigns aimed at dispelling doubts and eliminating obstacles to village governance. Assessment and Supervision: At the onset of the reforms, the provincial government established a Village Governance Office with a dedicated Assessment Division that managed the investigation and evaluation of village governance in the province’s 105 counties, divided into 12 districts. Additionally, each county was assigned a Village Governance Commissioner tasked with providing assistance, guidance, and on-site inspections. [18]

2.2.2 Standardization and Categorization (Grading)

Villages were categorized into different types and levels based on specific criteria, with corresponding measures applied to each category. The primary criteria for grading villages were: The general state of the village. The quality of village governance outcomes. The level of attention given to village affairs. This grading system allowed for tailored approaches to village governance reform.

2.2.3 Pilot Projects and Phased Implementation

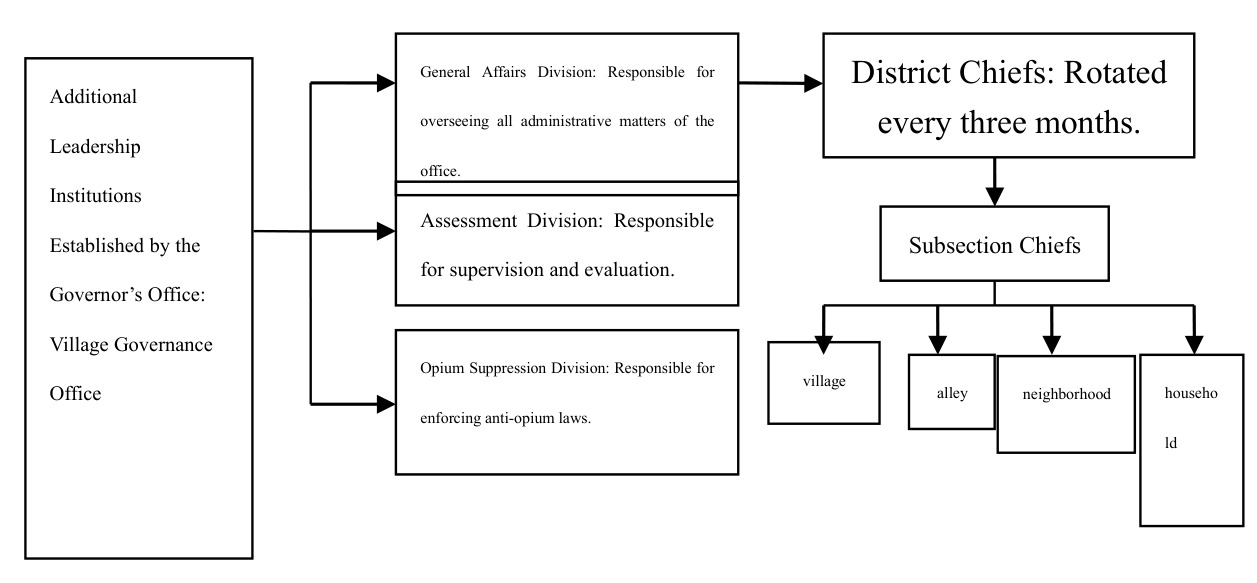

After formulating the governance reform policies and facilities, pilot projects were conducted in three counties: Yangqu, Yuci, and Taiyuan, as well as in urban areas of the provincial capital. By June 1922, the pilot program was expanded to include five additional counties: Pingding, Shouyang, Taigu, Xin County, and Dingxiang. Province-Wide Implementation: Once the pilot programs proved effective, reforms were rolled out across the province. In September and October 1922, the Shanxi Provincial Government convened two village governance conferences with participation from over 90 counties. During these conferences, county magistrates engaged in in-depth discussions on the principles, methods, processes, challenges, and tools for improving village governance. By the conclusion of the conferences, all participants pledged to prioritize "village-based politics grounded in the spirit of the people." [19] Supportive Infrastructure: Each county was assigned a Village Autonomy Assistance Commissioner to help implement village autonomy. In August 1922, the Village Governance Office was established in the provincial capital as the central agency for guiding village-based politics. It included the following divisions: General Affairs Division: Managed all administrative matters. Assessment Division: Oversaw evaluation and inspection. Opium Suppression Division: Enforced anti-opium laws.

Figure 1. Key Institutions of Village-Based Politics

By this stage, the core governance structure at the village level had been fully established. Key measures—such as reorganizing village norms, convening villager meetings, enacting village bans, establishing dispute mediation committees, and forming defense groups—were implemented across Shanxi. In 1927, Village Supervisory Committees were introduced in each administrative village, further refining the autonomy system and its institutional framework. These reforms contributed to: Economic development in modern Shanxi. Social progress and stability. As a result, Yan Xishan's village autonomy reforms hold a significant place in the modern history of Shanxi.

3 The Contemporary Implications of Yan Xishan’s Rural Construction

3.1 Yan Xishan's Rural Construction Emphasized Agriculture Development

In modern Shanxi, agriculture was the most significant industry in the national economy. Despite the growth of imperialist, bureaucratic capitalist, and national capitalist industrial and commercial enterprises, agriculture still accounted for the largest share of the economy. The primary role of agriculture was to provide food for the population, a particularly critical issue in war-torn China, where food security was a key concern for any political regime. Yan Xishan placed great emphasis on agriculture in his rural construction policies, implementing initiatives such as the “Six Policies” and “Three Tasks” to promote agricultural development. Today, in the context of building socialist new rural areas, the foundational role of agriculture remains irreplaceable. Addressing the food security of over one billion people continues to be a top priority in national governance. Adhering to the principle of basic self-sufficiency in grain production, accelerating the modernization of agriculture, and ensuring stable and sustainable agricultural development are crucial for driving agricultural economic growth and building a harmonious socialist society.

3.2 Yan Xishan's Rural Construction Valued Science and Experimentation

Yan Xishan established institutions such as the Agriculture and Sericulture Bureau, Cotton Industry Experimental Factory, and Model Animal Husbandry Farms as part of his “Six Policies and Three Tasks” initiative. He emphasized scientific experimentation and economic development. During the village governance reforms, experimental methods were used to pilot programs, showcasing a scientific approach. In the new era, the fundamental solution to agricultural development lies in technological progress. In today’s socialist new rural construction, it is imperative to: Increase investment in agricultural science and technology. Promote independent innovation in agricultural technology. Foster a scientific spirit of truth-seeking and pragmatism. Encourage bold experimentation and exploration. This approach will help accumulate experience, understand the principles of new rural construction, and develop innovative models. It also requires expanding the pool of agricultural science and technology talent, promoting agricultural technology dissemination, and conducting farmer training programs to cultivate new farmers who are educated, skilled, and capable of management. The active participation of millions of farmers is essential to building new rural areas.

3.3 Yan Xishan's Rural Construction Focused on Village Autonomy and Governance

Yan Xishan actively promoted the establishment of village governance systems, aligning with the trend of local autonomy during modern times and setting an example for rural self-governance nationwide. Policies such as the village organization system, direct democracy, and village governance supervision mechanisms standardized grassroots governance in Shanxi, stabilizing rural society. These practices remain relevant for contemporary China’s efforts to build grassroots democracy in rural areas. In today’s new rural construction, grassroots democracy remains a central element. It is essential to: Innovate governance systems and create dynamic village autonomy mechanisms under the leadership of village Party organizations. Expand the scope of village autonomy. Strengthen grassroots governance structures. Guarantee farmers’ political, economic, and cultural rights, including the rights to information, participation, expression, and oversight, in accordance with the law.

3.4 Yan Xishan's Rural Construction Addressed Farmers’ Needs

Whether through promoting education, advocating morality, or reorganizing village systems, Yan Xishan's rural construction largely reflected the production and living needs of farmers. In the contemporary context of socialist new rural construction, safeguarding and advancing the fundamental interests of farmers must remain the starting point and endpoint. It is necessary to adhere to the principle of “people-centered development” by: Ensuring farmers’ political, economic, cultural, and social rights. Improving farmers’ overall quality and fostering their comprehensive development. Only by doing so can farmers’ central role and innovative spirit be fully realized. This approach will also transform rural social resources into social capital, enabling rapid and stable advancement of new rural construction initiatives and achieving balanced, sustainable development.

Yan Xishan governed Shanxi for 38 years, making him one of the longest-serving figures in local autonomy during the Republic of China. His longevity in power was closely tied to the series of policies he implemented, including rural construction. However, due to the limitations of his era and personal circumstances, Yan Xishan's rural construction could not fundamentally solve the challenges facing rural development in old China. Nonetheless, some of his specific measures, institutional innovations, and practices in rural construction offer valuable historical lessons. It is essential to respect Yan Xishan's originality, recognize his historical contributions, and extract the rational elements of his legacy. These lessons are highly relevant for addressing contemporary "agriculture, rural areas, and farmers" issues, developing grassroots democracy, improving rural governance structures, and promoting socialist new rural construction. Yan Xishan's efforts provide important insights and serve as a meaningful reference for modern development.

References

[1]. Academy of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Republican History Research Office, et al. (Eds.). (1982). The Complete Works of Sun Yat-sen. Zhonghua Book Company, p. 471.

[2]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 54.

[3]. Jiang, D. (1988). Modern Shanxi. Shanxi People's Publishing House, p. 132.

[4]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, pp. 54, 57.

[5]. Yan, Y. C., Wang, W. X., et al. (1928). Xiangyuan County Gazetteer, Vol. 2. Lithographed edition, p. 4.

[6]. Guo, B. L., et al. (1925). Shanxi Local System Survey Report. Shandong Public Agricultural Specialized School Survey Association, p. 2.

[7]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 6.

[8]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, pp. 84–85.

[9]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 11.

[10]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 86.

[11]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 25.

[12]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 56.

[13]. Yan, X. S. (1929). Compilation of the Six Policies and Three Affairs of Shanxi (Preface). Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 1.

[14]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 5.

[15]. Shanxi Provincial CPPCC Historical Research Committee. (1984). Historical Facts of Yan Xishan's Rule of Shanxi. Shanxi People's Publishing House, p. 72.

[16]. Shanxi Village Administration Office. (1928). Compilation of Shanxi Village Governance (Official Reports). Shanxi Provincial Government Village Administration Office, p. 1.

[17]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 7.

[18]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 21.

[19]. Shanxi Village Administration Office. (1928). Compilation of Shanxi Village Governance, Vol. 8. Shanxi Provincial Government Village Administration Office, p. 4.

Cite this article

Wu,G. (2025). Yan Xishan's Rural Construction and Its Contemporary Implications. Advances in Humanities Research,11,69-76.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Academy of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Republican History Research Office, et al. (Eds.). (1982). The Complete Works of Sun Yat-sen. Zhonghua Book Company, p. 471.

[2]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 54.

[3]. Jiang, D. (1988). Modern Shanxi. Shanxi People's Publishing House, p. 132.

[4]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, pp. 54, 57.

[5]. Yan, Y. C., Wang, W. X., et al. (1928). Xiangyuan County Gazetteer, Vol. 2. Lithographed edition, p. 4.

[6]. Guo, B. L., et al. (1925). Shanxi Local System Survey Report. Shandong Public Agricultural Specialized School Survey Association, p. 2.

[7]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 6.

[8]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, pp. 84–85.

[9]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 11.

[10]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 86.

[11]. Office of the Director of the Taiyuan Pacification Commission. (1925). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 3. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 25.

[12]. Yan, X. S. (1937). Collected Discourses of Mr. Yan Bochuan, Vol. 7. Office of the Pacification Commission, p. 56.

[13]. Yan, X. S. (1929). Compilation of the Six Policies and Three Affairs of Shanxi (Preface). Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 1.

[14]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 5.

[15]. Shanxi Provincial CPPCC Historical Research Committee. (1984). Historical Facts of Yan Xishan's Rule of Shanxi. Shanxi People's Publishing House, p. 72.

[16]. Shanxi Village Administration Office. (1928). Compilation of Shanxi Village Governance (Official Reports). Shanxi Provincial Government Village Administration Office, p. 1.

[17]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 7.

[18]. Xing, Z. J. (1929). General Outline of Shanxi Village Governance. Shanxi Village Administration Office, p. 21.

[19]. Shanxi Village Administration Office. (1928). Compilation of Shanxi Village Governance, Vol. 8. Shanxi Provincial Government Village Administration Office, p. 4.