1. Data and methods

1.1. Data sources and time selection

This study uses the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database as its data source. Established in 1999, CNKI is currently the largest database in China, offering a diverse range of document types that cover nearly all academic disciplines. Its high-quality thesis and dissertation records and vast collection of literature make it one of the most important sources for academic research in China. The study conducts a keyword search using the theme “intangible cultural heritage” and “community,” beginning with the release of the “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” in 2003. The search period is limited from January 1, 2003, to March 1, 2025. A total of 235 documents were retrieved from CNKI journals. To ensure the relevance and validity of the documents, manual verification was conducted to eliminate non-academic materials such as prefaces, call-for-papers, recruitment notices, book reviews, and conference announcements. After the review process, 206 valid documents were retained [1].

1.2. Research methods

This study employs bibliometric methods, which were first proposed by Pritchard in 1969. Bibliometrics refers to the quantitative analysis of various types of literature to uncover underlying patterns and potential information, thereby providing new insights into the current state and development trends of a specific research field. For empirical analysis of the retrieved data, this study uses CiteSpace (6.4.R3), a bibliometric visualization software [2].CiteSpace is a data visualization analysis tool developed collaboratively by Professor Chen Chaomei of Drexel University (USA) and the WISE Lab at Dalian University of Technology [3]. It primarily helps researchers gain a better understanding of the development trends within different disciplines. In recent years, this bibliometric visualization software has been widely applied in bibliometric analysis. Its greatest advantage lies in its ability to collect large data samples in a visual format, helping researchers more efficiently and comprehensively understand the development trends in the field, without relying on traditional meso-level system evaluations or micro-level meta-analysis methods.

2. Statistical results analysis

In China, Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) refers to various traditional cultural expressions passed down from generation to generation by different ethnic groups, considered as part of their cultural heritage, along with the associated physical objects and locations [4]. ICH is not only the most vibrant component of cultural diversity but also the crystallization of human civilization and the most precious shared wealth, carrying human wisdom and the brilliance of history [5]. The term “ICH community” mentioned in this field of study refers to a model of ICH protection and inheritance carried out at the community level. This model emphasizes integrating ICH into the daily lives of community residents through various activities and projects, allowing residents to personally experience and learn about ICH, thereby strengthening the community’s cultural identity and cohesion. ICH, as a traditional cultural expression passed down through generations by word of mouth, has high recognizability and ethnic characteristics.

The combination of “ICH” and “community” is of great significance. On one hand, the protection and inheritance of ICH require specific practical fields, and as the fundamental unit of residents’ lives, the community is the natural soil for ICH inheritance. Integrating ICH into the community allows it to be passed on in a living form in residents’ daily lives, avoiding disconnection from modern society. On the other hand, the inheritance of ICH requires not only policy promotion but also widespread participation and recognition from community residents. Through the construction of ICH communities, the intrinsic motivation of residents can be stimulated, shifting ICH protection from “passive preservation” to “active inheritance,” thus enhancing the community’s cultural cohesion and sense of identity. From the perspective of ICH, as a living culture, it needs to be inherited and developed within a specific social environment. The community, as the core space of residents’ lives, is the natural soil for ICH inheritance. Integrating ICH into the community ensures its continuous transmission and practice in residents’ daily lives, preventing it from gradually disappearing due to disconnection from life. From the community’s perspective, cultural construction requires rich cultural connotations and broad resident participation. As the most ethnically distinctive and recognizable cultural heritage, ICH can provide a unique cultural identity for the community, strengthening its cultural cohesion and sense of belonging. The construction of ICH communities can ignite residents’ interest in and awareness of protecting local culture, promoting the sustainable development of community culture.

From the relationship between the two, the combination of ICH and community is a win-win model. ICH provides cultural resources for the community, and the community offers a platform for ICH inheritance. This combination not only aids in the protection and inheritance of ICH but also promotes the prosperity of community culture and the harmonious development of society. Therefore, this paper will use bibliometric methods to conduct a quantitative and visual analysis of relevant literature on domestic ICH community research, providing an overall overview and knowledge foundation for researchers in this field.

2.1. Analysis of total number of publications

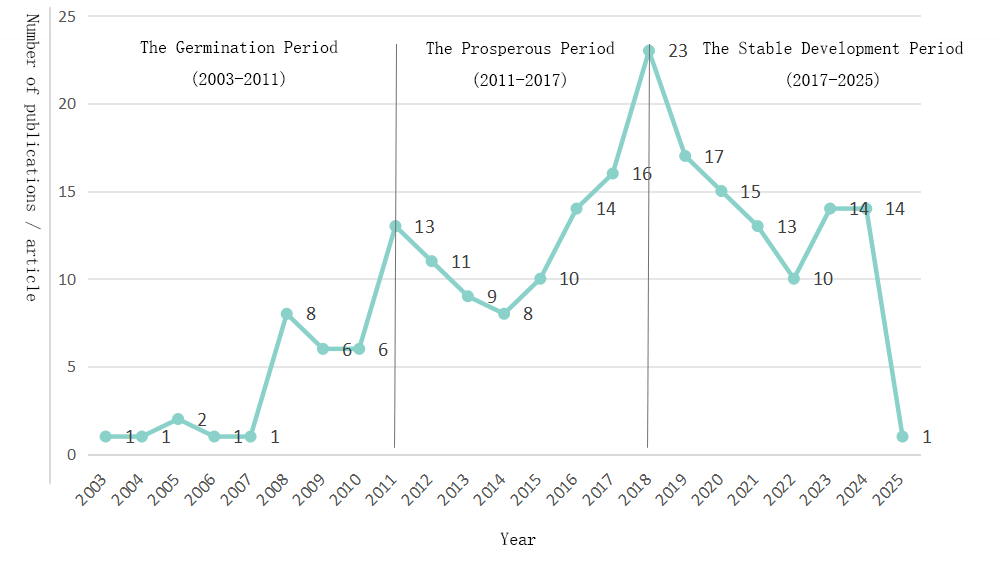

The number and timing of publications can reveal the academic evolution characteristics of a specific field. The distribution of research papers published in journals, along with their year-wise publication counts, is shown in Figure 1 [1]. Publications began in 2003, gradually increasing over time. The number of publications fluctuated significantly between 2011 and 2017. Despite some fluctuations between 2019 and 2021, likely due to the impact of the pandemic on academic activities, the number of publications became relatively stable after 2017. Following that period, the publication rate remained steady at around 15 articles per year, reflecting the growing national attention to intangible cultural heritage (ICH) and the introduction of relevant policies. Moving forward, ICH communities are expected to become an increasingly important focus for both academia and industry.

Figure 1. Number of publications on ICH community research in journals

2.2. Spatial distribution characteristics of the literature

2.2.1. Journal distribution

Among the data retrieved for this field, there are 167 journal articles, 21 master’s/doctoral theses, and 10 conference papers. The distribution of journal articles in related popular science journals shows the following characteristics: First, of the 206 valid documents collected, 66 are from CSSCI journals [6], accounting for approximately 32.0%. This indicates that the quality of research output in journals needs further improvement. Second, the journal with the highest number of publications is Northwest Ethnic Studies, with 10 articles published. This journal is an important academic platform in the field of ICH, and over the past 30 years since its establishment, it has become a major academic forum for ethnic ICH culture [1], dedicated to researching ethnic issues, anthropology, and sociology. The second journal with the most publications is Cultural Heritage, which published 8 articles. Its mission is to “promote excellent Chinese culture and prosper the study of cultural heritage,” focusing on building a theoretical framework for Chinese cultural heritage research and providing strong theoretical support for the protection and development of Chinese cultural heritage. Finally, Folk Culture Forum published 7 articles, with a focus on “promoting Chinese folk culture” and emphasizing multidisciplinary perspectives in the study of folk culture.

2.3. Core author analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the research progress in a specific field, analysis of its core authors is essential. The research achievements of core authors represent the level and direction of research in that field, as shown in Table 1 [8]. According to Price’s law (1), authors with more than m published papers are considered core authors [7].

\( {M_{P}}=0.749\sqrt[]{{N_{P max}}}\ \ \ (1) \)

Statistical analysis reveals that there are five core authors in the field of ICH community research. Among them, one author, Ma Qianli, has published 8 papers, while the other four authors—Tang Lulu, Wang Yonggui, Zheng Wenqing, and An Deming—have each published 3 papers. This indicates that high-output authors in this field are scarce, and there is still significant room for research.

Table 1. Author publication count

No. | Publication Count | Year | Author |

1 | 8 | 2018 | Ma Qianli |

2 | 4 | 2016 | Tang Lulu |

3 | 3 | 2011 | Wang Yonggui |

4 | 3 | 2018 | Zheng Wenqing |

5 | 3 | 2016 | An Deming |

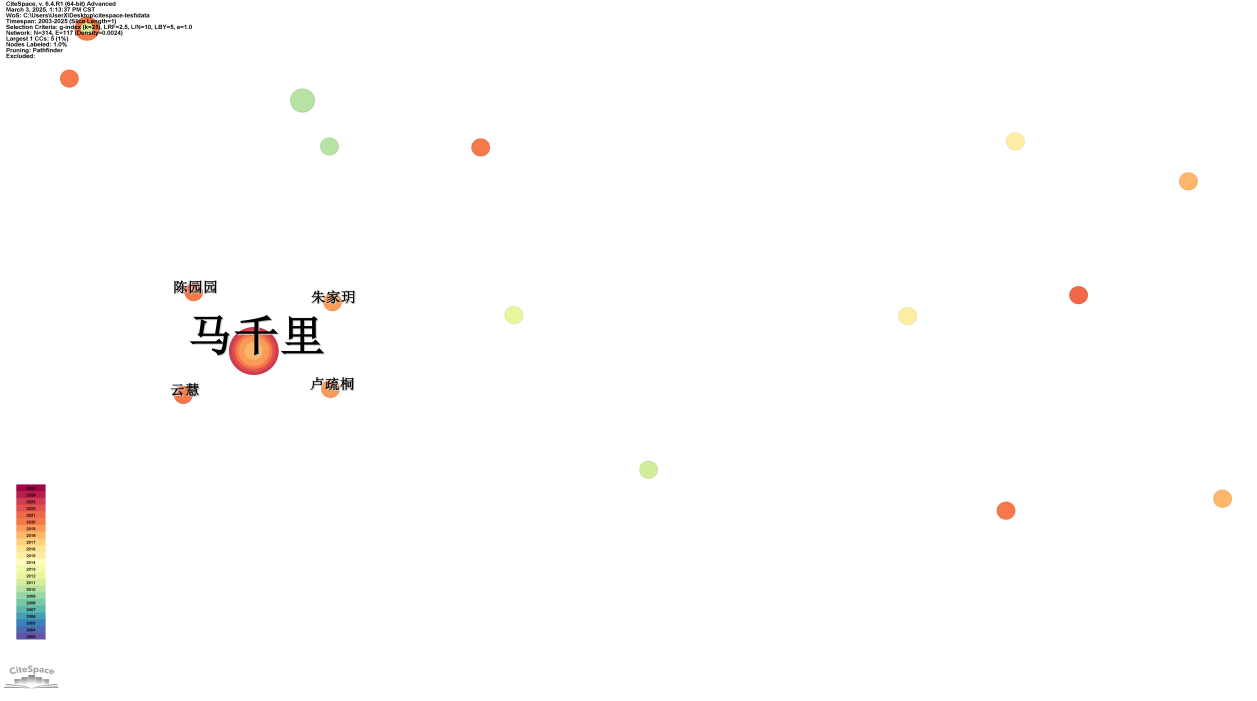

Additionally, by using CiteSpace software and analyzing authors as node types, a co-authorship network of core authors is generated, as shown in Figure 2. The report shows that there are 516 author nodes with 253 connections, and the density is 0.0019, with a value of 0.9764 [6]. “A value greater than 0.3 indicates that the network’s community structure is significant, and the closer the value is to 1, the better the clustering of the network” [6]. The co-authorship connections between core authors in Figure 2 are sparse and dispersed, with a low node density, indicating that the collaborative relationships in popular science journal research are fragmented. Most collaborations occur within institutions, and overall, a multi-level and cohesive research team has not yet formed. The frequency and intensity of collaboration between scholars still need to be enhanced [6].

Figure 2. Core author co-occurrence map of research journals

2.4. Institutional distribution

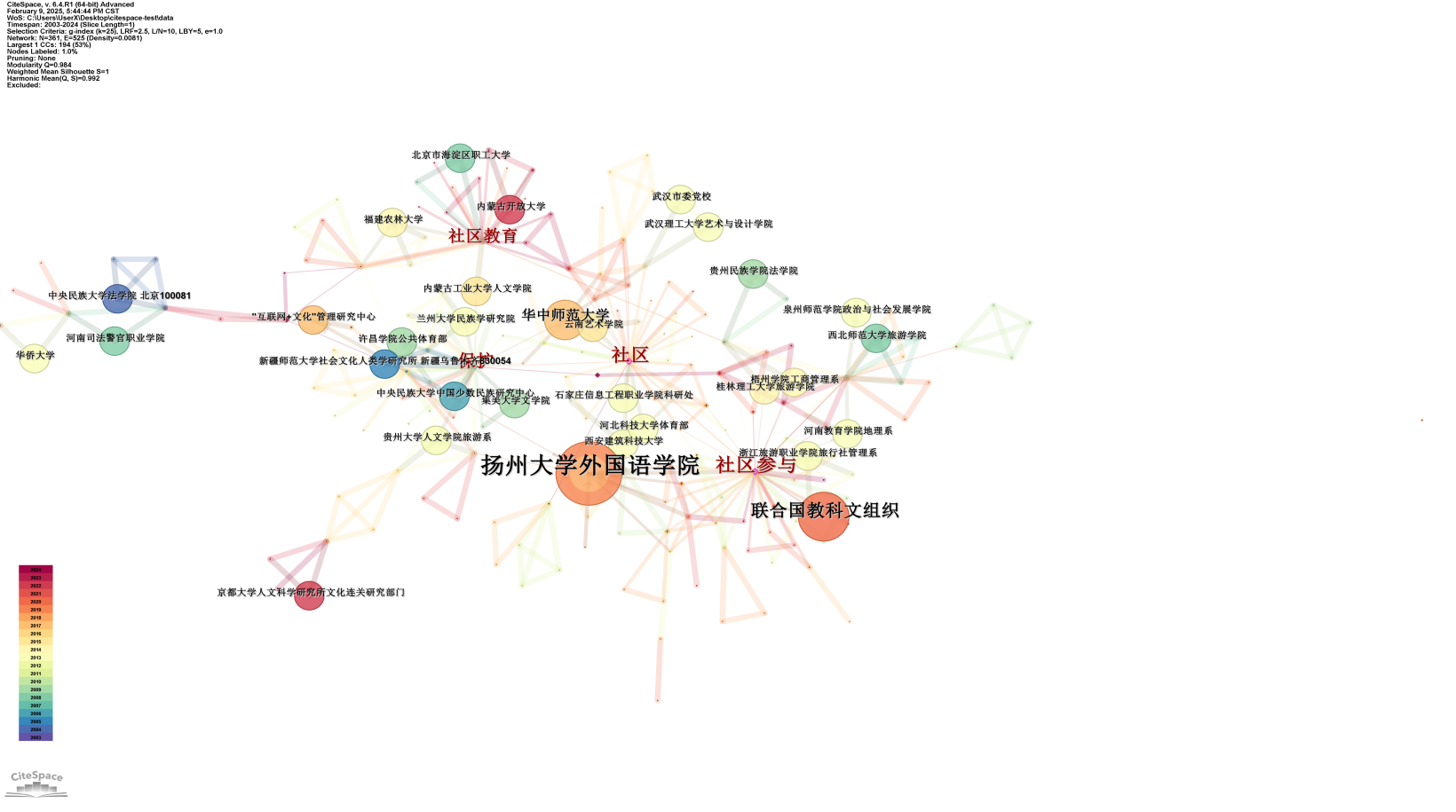

CiteSpace software was used to analyze the research institutions related to the ICH community in the valid sample, resulting in the collaboration institution distribution map shown in Figure 3. The analysis reveals that the 206 documents involve multiple research institutions, including higher education institutions, government departments, popular science research organizations, social organizations, and other entities [6]. The institution with the highest number of publications has only 7, and schools dominate in terms of publication volume, holding the position of research subject position. Unlike other research fields, most of the studies are supported and encouraged by the government. Looking at the line thickness and inter-institutional cooperation relationships, the lines between nodes are few and the node density is low. Moreover, the larger the circle of a node, the more publications it has, indicating insufficient cooperation and communication between institutions, with cross-institutional collaboration needing improvement.

Figure 3. Co-occurrence map of research institutions in journal publications

3. Keyword analysis

3.1. Keyword co-occurrence analysis

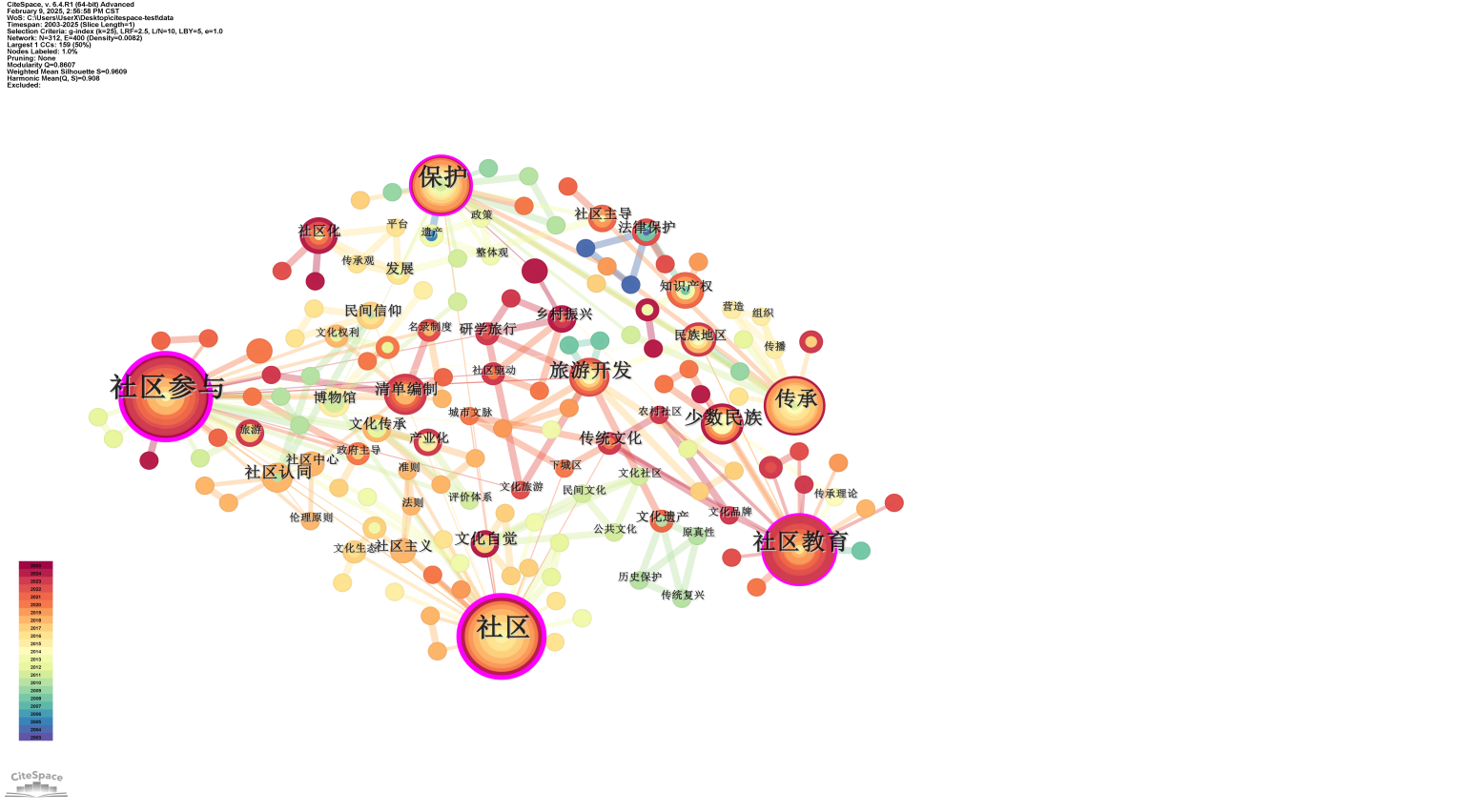

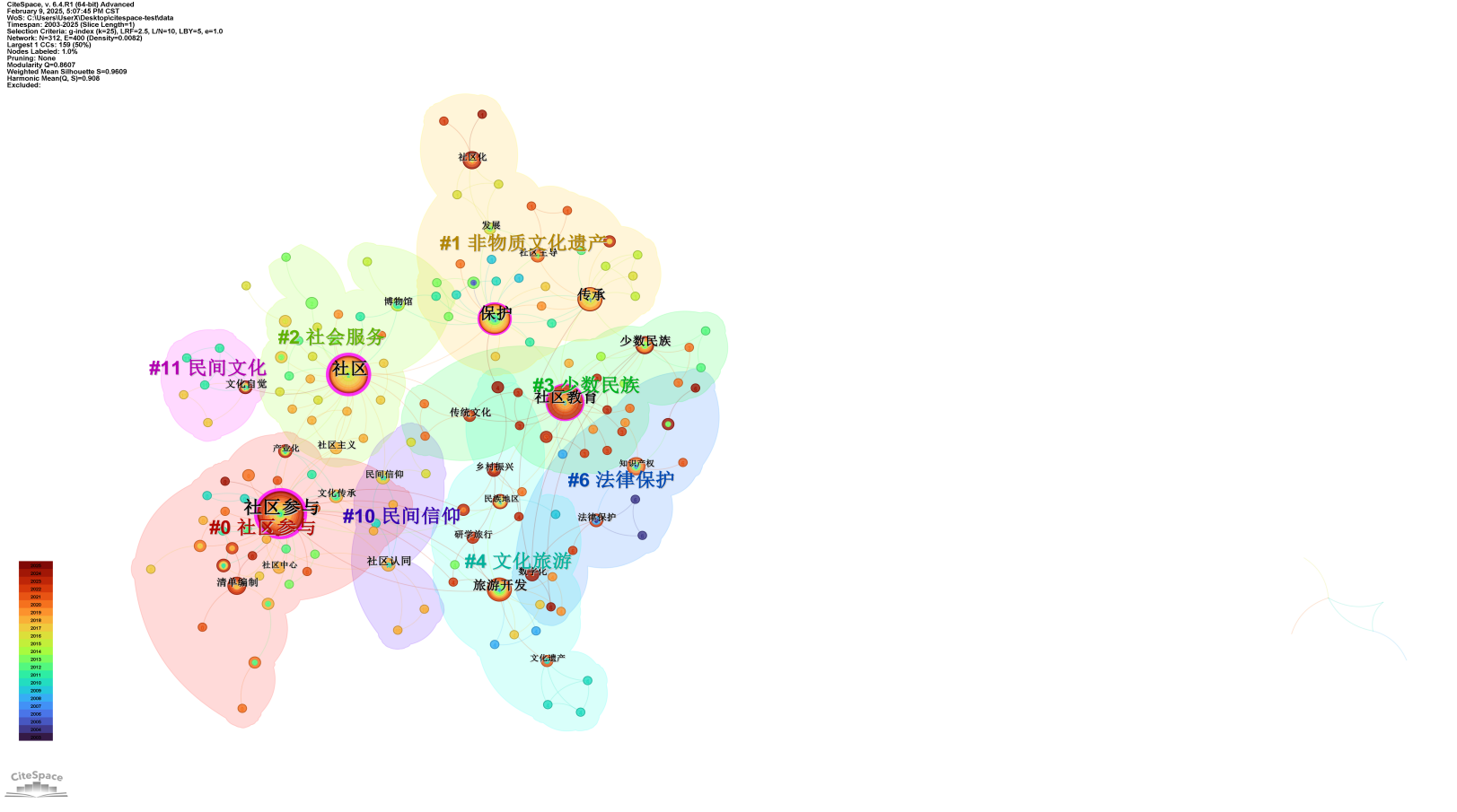

Keywords are a highly condensed and summarized representation of the topics in the literature. By analyzing the high-frequency keywords in the literature, it is possible to reveal the research hotspots [8], trends, and the relationships between different research topics. For the valid literature, CiteSpace software was used to conduct high-frequency keyword analysis, resulting in 312 nodes and 400 connections, with a node density of 0.0082. The keyword co-occurrence map for the 2003-2025 journal research field is shown in Figure 4 [9]. In Figure 4, the size of the node reflects the frequency of occurrence of the keyword. The larger the node, the higher the frequency of the keyword. The color of the node represents the active time period of the keyword [10], with the color changing from the inside to the outside indicating the publication time range from early to present. The thickness of the purple outer circle of the node represents the citation frequency of the keyword, i.e., its centrality. The study found that “community participation,” “community,” “community education,” “protection,” and “inheritance” are the five core keyword nodes. These keywords occupy a central position in the ICH community field, and a wide range of radial connections are formed around them, creating a complex structural network [11]. These connections primarily link to “intellectual property,” “ethnic regions,” “ethnic minorities,” and “tourism development,” suggesting that the journal research field has developed a certain content system and that cross-disciplinary research is already taking place [12].

Figure 4. Co-occurrence network map of journal research keywords

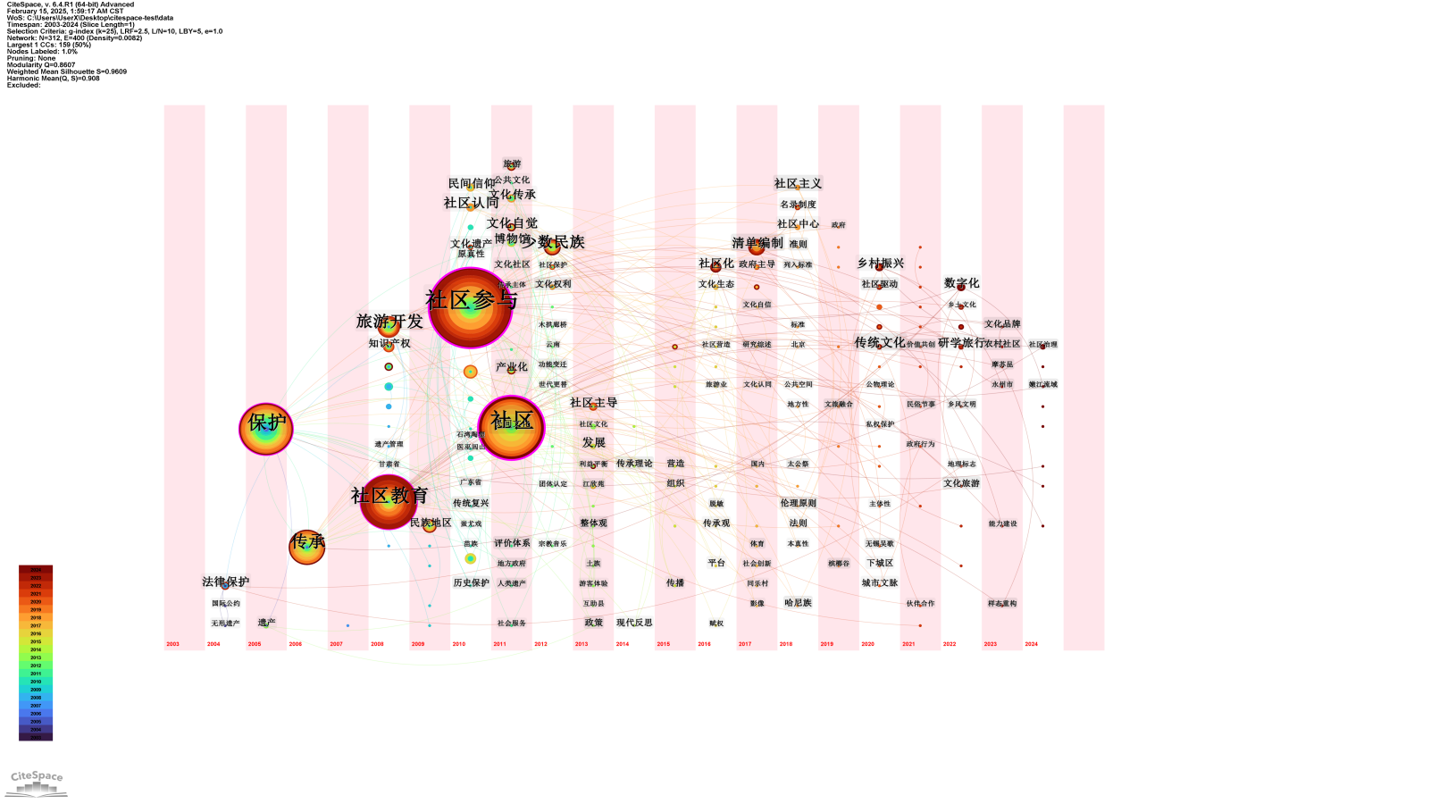

3.2. Keyword clustering map analysis

The keyword clustering map groups similar keywords into different clusters, revealing the main themes and research directions in the field. It helps researchers quickly identify research hotspots, the relationships between themes, and the development trends of the field. CiteSpace software was used to perform keyword clustering, grouping keywords with similar characteristics as clustering objects [13], as shown in Figure 5. This resulted in 8 keyword clusters labeled #0 to #11, which are as follows: #0 Community Participation, #1 Intangible Cultural Heritage, #2 Social Services, #3 Ethnic Minorities, #4 Cultural Tourism, #6 Legal Protection, #10 Folk Beliefs, and #11 Ethnic Culture. Based on this, the thematic classification of the journal research field can be further extracted [12]. Since some clustering terms contain similar words, to further summarize the academic research hotspots, similar clustering terms were merged. Then, high-frequency keywords and high-centrality keywords were used for further categorization [14], resulting in a summary of the main knowledge groups in the ICH community research field.

Figure 5. Keyword clustering map of journal research

3.3. Keyword emergence and time zone analysis

Conducting a keyword emergence analysis (including emerging keywords, emergence strength, and start and end times) for the research subject can clearly present the historical development of the research field [15]. The top 21 keywords with the highest emergence strength in the field of ICH community journal research were selected for quantitative statistics, generating the keyword emergence map and the time zone map for keyword clustering, as shown in Figure 6 [16]. Analyzing Figure 6, the following characteristics can be summarized: First, based on the start year of keywords becoming research hotspots, topics related to “community,” “grassroots community,” “community education,” and “protection” began their research in 2011, 2008, and 2005, respectively, making them earlier research hotspots, whereas topics such as “digitalization” became hotspots later, starting in 2022 [17]. Second, in terms of the duration of research hotspots, topics related to “folk art” lasted the longest, from 2010 to 2016, lasting for 8 years. Third, 2022 was the “outburst period” for keyword emergence in this field, generating four hot keywords: “digitalization,” “research-based travel,” “local culture,” and “community empowerment,” all of which became highly popular during that year. This indicates that most popular keywords were extensively researched in earlier periods. Fourth, in terms of emergence strength, “community” ranked first with a score of 2.83, which aligns with the current research hotspots and reflects the gradual transformation of ICH communities [18]. Other keywords with significant emergence strength, such as “community education,” “protection,” “grassroots community,” “digitalization,” and “tourism development,” have also become major hotspots in scientific journals [19].

Table 2. Time distribution analysis of journal emergent keywords

Keywords | Year | Strength | Begin | End | 2003 - 2025 |

Community | 2011 | 2.83 | 2015 | 2018 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Community Education | 2008 | 2.75 | 2019 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂ |

Protection | 2005 | 1.88 | 2005 | 2011 | ▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Grassroots Community | 2008 | 1.73 | 2008 | 2010 | ▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Digitalization | 2022 | 1.53 | 2022 | 2025 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃ |

Tourism Development | 2008 | 1.44 | 2013 | 2014 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

ICH | 2010 | 1.39 | 2016 | 2017 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Museum | 2011 | 1.35 | 2011 | 2015 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Inheritance | 2006 | 1.31 | 2014 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Folk Art | 2010 | 1.29 | 2010 | 2016 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Ethnic Minorities | 2012 | 1.29 | 2012 | 2014 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

List Preparation | 2017 | 1.26 | 2017 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂ |

Legal Protection | 2004 | 1.22 | 2004 | 2008 | ▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Rural Revitalization | 2020 | 1.15 | 2020 | 2025 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃ |

Research-based Travel | 2022 | 1.14 | 2022 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂ |

Local Culture | 2022 | 1.14 | 2022 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂ |

Cultural Ecology | 2016 | 1.11 | 2016 | 2017 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Cultural Heritage | 2011 | 1.05 | 2011 | 2012 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Community Empowerment | 2022 | 1.02 | 2022 | 2025 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃ |

Development | 2013 | 1 | 2013 | 2016 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

Folk Beliefs | 2010 | 0.97 | 2016 | 2017 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

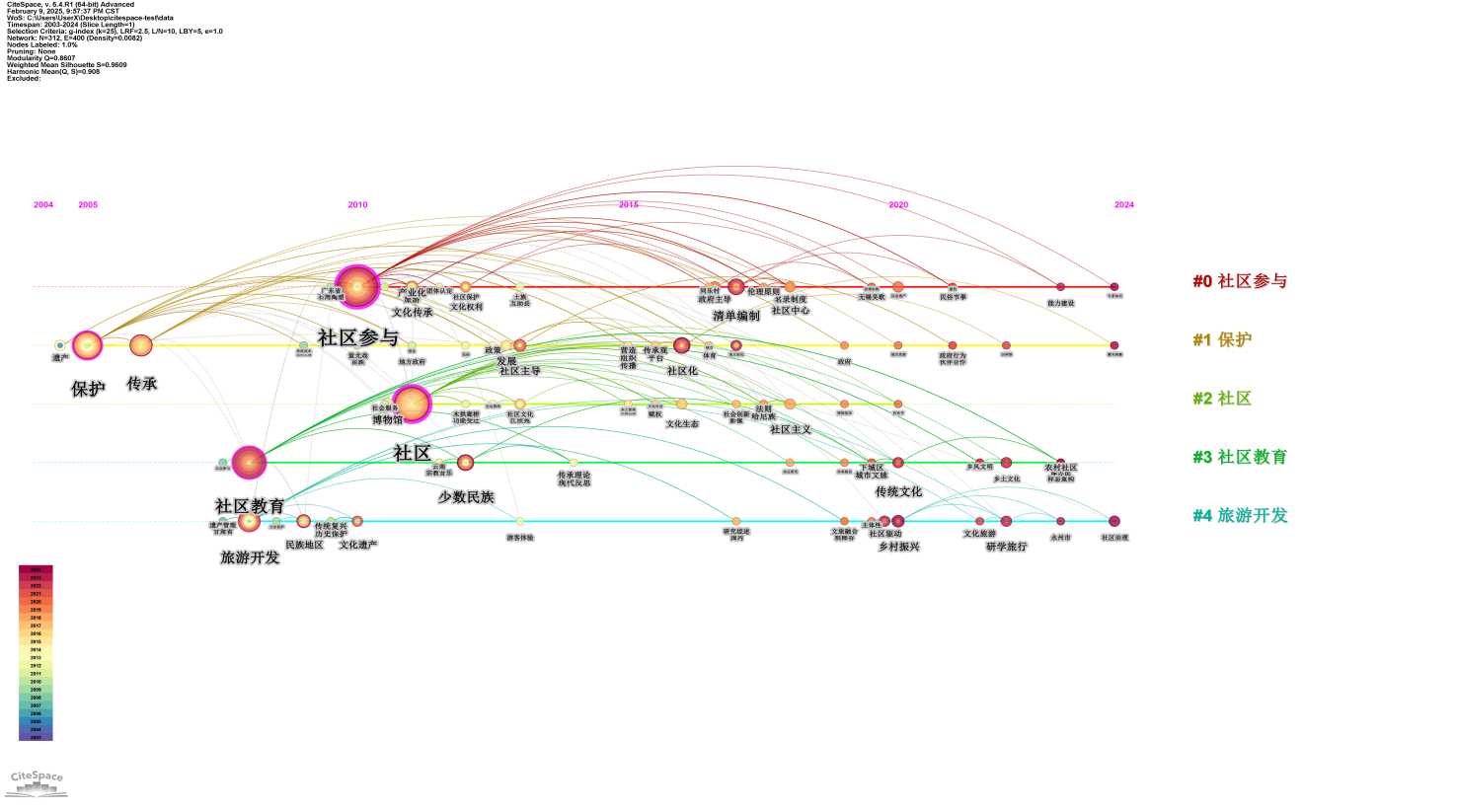

A time zone analysis was conducted on the research subjects, as shown in Figures 7 and 8. The time zone chart introduces time as an important dimension in the visualization analysis. The analysis of the chart reveals that the keyword “protection” first appeared as early as 2005. In the time zone chart, the lines connecting keywords represent their co-occurrence relationships. The span of the lines shows the ongoing development of these keywords, while the thickness of the lines indicates the frequency of co-occurrence [20]. The higher the frequency, the thicker the line. For example, keywords like “community,” “community education,” and “community participation” show a strong correlation between them. These clusters are displayed in chronological order from 2003 to 2025, providing a more intuitive view of the activity levels and mutual influences of different clusters during various time periods. Finally, the time zone chart reveals the evolution of research topics, shifting from “protection” to “community” and then to “community-based.” This evolution clearly illustrates the research hotspots and trends in this field during different time periods, allowing for the identification of future development directions and frontier dynamics in the field [21].

Figure 6. Journal research keyword time zone analysis map

Figure 7. Research keyword clustering time map

4. Future outlook of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) community research

In the new century, driven by both policy and market forces, ICH communities will focus on enhancing community subjectivity, promoting digital protection, facilitating living inheritance, and strengthening international exchanges. At the same time, ICH protection will aim for sustainable development [22]. First, from an academic research perspective, the study of community subjectivity can be deepened. Further exploration is needed into the central role of communities in ICH protection, emphasizing the internal heterogeneity of communities, diverse interests, and the establishment of community-led endogenous mechanisms. Research will focus more on the agency of community members and cultural identity, advancing the transformation of ICH protection from “entering communities” to “existing within communities.” Next, interdisciplinary research will be expanded. ICH community research will strengthen cross-disciplinary collaboration with fields such as folklore, sociology, anthropology, and cultural economics, creating a more comprehensive theoretical framework [23]. For example, through protection strategies from a cultural gene perspective, the sustainable development of ICH in modern society will be explored. Finally, research will focus on how ICH can aid rural revitalization through tourism development and community cooperation, using the integration of ICH and rural revitalization to play a role in rural governance, cultural inheritance, and economic development.

4.1. Research topic: digital and intelligent protection

With continuous technological progress, the protection of ICH communities will increasingly rely on digital technologies such as virtual reality and artificial intelligence to achieve digital protection and dissemination of ICH [24]. The application of such technologies not only improves protection efficiency but also enables more people to access ICH through new media platforms. In the future, ICH protection will place greater emphasis on community participation and cultural dialogue, balancing government-led and community-driven initiatives to foster a positive atmosphere for ICH inheritance. Through division of labor and cooperation within the community, ICH protection will become community-led. ICH protection will shift from mere preservation to living and dynamic inheritance, emphasizing the integration of ICH into social life as a “living resource” [25]. For example, by combining ICH with modern design and the fashion industry, more ICH products that meet contemporary aesthetic standards can be created.

4.2. Research method: strengthening communication and exchange

The international dissemination of ICH will become an important trend in the future. China will actively participate in international ICH protection projects, learning from the successful experiences of other countries through international exchanges and further improving its own ICH protection model [26]. At the same time, greater policy support will be provided, with more measures to support ICH protection and inheritance, including financial investment and tax incentives. Policies will also focus more on the sustainability of ICH protection, promoting the deep integration of ICH and community development [27]. In addition, the ICH market shows strong growth potential, and ICH will engage in more cross-industry collaborations with tourism, education, cultural creativity, and other industries, expanding the space for ICH culture to develop. It is expected that the market size will continue to grow in the coming years. Finally, ICH will play an important role in community governance and enhancing community cohesion. Regional features and community governance in different areas will explore ICH protection models with regional characteristics based on local cultural features [28].

5. Conclusion

This study takes the field of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) and community research as its entry point and, using the knowledge mapping tool CiteSpace, conducts a visual analysis of relevant journal literature in China since the beginning of the new century. The knowledge map is constructed from multiple dimensions, including high-frequency keywords, highly cited literature, keyword clustering, and time series changes, in order to deeply analyze the research progress, hotspots, and trends in this field. In terms of research methodology, this study employs a quantitative approach to analyze existing literature. Compared to traditional methods of literature processing, this approach offers significant objectivity and accuracy. The charts generated by CiteSpace are intuitive and vivid, clearly presenting the research context and key nodes. However, due to the dynamic nature of literature retrieval and the modeling limitations of the software tool, future research should further strengthen qualitative analysis on the basis of quantitative analysis, organically integrating quantitative research with qualitative analysis.

Moreover, more diversified research methods could be explored to provide a more comprehensive and objective representation of China’s ICH and community research. Due to the limitations of literature database coverage and the parameter settings of software algorithms, future studies should build a “quantitative analysis-based, qualitative research-oriented” hybrid methodological framework. This could include the introduction of grounded theory, comparative research, and other diverse methods, which would enhance the depth of theoretical interpretation while maintaining the objectivity of data. Through this comprehensive research approach, this study aims to provide deeper theoretical support and practical guidance for ICH and community research, promoting the further development of this field.

References

[1]. Yan, W. (2024). Progress, hotspots, and trends in Chinese popular science journal research: A visualization analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map. Chinese Journal of Science and Technology Periodicals, 35(02), 163-170.

[2]. Yi, K. (2024). A literature-based review of museum experience design research: A bibliometric analysis. Packaging Engineering, 45(20), 272-284. https://doi.org/10.19554/j.cnki.1001-3563.2024.20.025

[3]. Tang, L. (2024). A visual analysis of research on ideological and political education in university English courses: A statistical analysis of CNKI literature from 2018 to 2023. Journal of Wuzhou University, 34(01), 90-99.

[4]. Liu, L. (2018). Research on the intangible cultural heritage of Bailu Ancient Village in the context of the post-industrial era (Master’s thesis). Gan Nan Normal University.

[5]. Huang, S., & Chen, W. (2024). Research on visual culture innovation in the digital dissemination of intangible cultural heritage. Cultural Exchange between China and Foreign Countries, (10), 106-108.

[6]. Yan, W., & Wang, J. (2025). Twenty years of rural communication research in China: Hotspots, evolution, and outlook — A visualization analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map. Southeast Communication, (01), 44-49. https://doi.org/10.13556/j.cnki.dncb.cn35-1274/j.2025.01.010

[7]. Peng, J. (2024). Research on the development of adult education courses for traditional craftsmanship intangible cultural heritage in communities (Master’s thesis). Sichuan Normal University. https://doi.org/10.27347/d.cnki.gssdu.2024.001453

[8]. Sun, J., & Yan, H. (2024). Using “community” as a method: Cultural heritage paths from the perspectives of sociology and anthropology. Southeast Culture, (06), 6-12.

[9]. Peng, M. (2025). From expert-led to community participation: The formation of public folklore in the United States and the “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Folklore Studies, (01), 62-74+157. https://doi.org/10.13370/j.cnki.fs.2025.01.004

[10]. Li, S. (2024). Research on the community-based inheritance of intangible cultural heritage: A case study of Gupo Song. Journal of Yangtze University (Social Science Edition), 47(06), 46-50.

[11]. Chen, X. (2024). Research on library strategies for community education and promotion in the protection of local cultural heritage. Media Forum, 7(14), 110-113.

[12]. Zhu, H., Wen, Y., & Zhang, H. (2024). Current status, hotspots, and trends in international deep leisure research: A knowledge map analysis based on the Web of Science core database (1982–2023). In Proceedings of the 1st National Outdoor Adventure and Leisure Sports High-Quality Development Seminar, 2nd National “Leisure Sports” National First-Class Undergraduate Program Construction Seminar, and 2nd Capital University Leisure Sports Academic Paper Report Conference (p. 15). Beijing Sport University, Sports Leisure and Tourism College. https://doi.org/10.26914/c.cnkihy.2024.014307

[13]. Xu, D., & Liu, Z. (2023). A review of the current status of Chinese foreign language research from the perspective of “new liberal arts”: A visual analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map (2018–2022). Journal of Guizhou Normal University, 39(2), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.13391/j.cnki.issn.1674-7798.2023.02.011

[14]. Tian, J. (2024). The protection and inheritance of intangible cultural heritage from a community perspective. China Ethnic Expo, (8), 26–28.

[15]. Pu, Y. (2021). A knowledge map analysis of research dynamics in hospital party building. Gansu Medical Journal, 40(4), 362–364+370. https://doi.org/10.15975/j.cnki.gsyy.2021.04.025

[16]. Zhang, J. (2024). Practical exploration of the role of intangible cultural heritage in urban community construction. Journal of Jingdezhen College, 39(2), 1–6.

[17]. Yang, H. (2024). Initial exploration of the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage in online virtual communities. Cultural Heritage, (2), 9–16.

[18]. Zhou, H. (2024). Discussion on the integration of intangible cultural heritage into community cultural construction. China Ethnic Expo, (4), 61–63.

[19]. Yang, L. H. (2023). “Bringing the community’s voice to the forefront”: Multiple practice models of intangible cultural heritage protection and community participation. Journal of Yunnan Normal University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 55(6), 45–55.

[20]. Zhang, M. F. (2023). Community education’s role in protecting intangible cultural heritage in ethnic regions of China. Journal of Qiqihar University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), (8), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.13971/j.cnki.cn23-1435/c.2023.08.013

[21]. He, T. T. (2023). Research on rural cultural heritage protection strategies under the concept of community museums: A case study of Shuyi Village in Changsha, Hunan Province. Village Committee Director, (6), 137–140.

[22]. Ju, Y. Y., & Cheng, L. (2023). The formation mechanism of heritage responsibility behavior in tourism communities at cultural heritage sites: Based on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Journal of Natural Resources, 38(5), 1135–1149.

[23]. Wang, Q. C. (2023). Listening to the voices of heritage owners (Doctoral dissertation). Guangxi University for Nationalities. https://doi.org/10.27035/d.cnki.ggxmc.2023.000235

[24]. Li, L. Y. (2023). Research on the reconstruction of community education inheritance paths for intangible cultural heritage: A case study of the Mosukun of the Oroqen nationality. Heilongjiang Ethnic Journal, (2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.16415/j.cnki.23-1021/c.2023.02.021

[25]. Shi, J. D. (2023). Inheritance paths of intangible cultural heritage in cultural ecological protection areas: From the perspective of residents’ community cultural participation. China Ethnic Expo, (3), 72–74.

[26]. Gu, C. X. (2023). Inheritance and aesthetic education practices of cultural heritage in “community scenes”. Cultural Education Materials, (3), 30–33.

[27]. Feng, L., & Zhao, J. W. (2022). Lived co-construction: Intangible cultural heritage protection practices in community museums. Northwest Ethnic Studies, (4), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.16486/j.cnki.62-1035/d.20220823.001

[28]. Li, F. (2022). Research on improving citizens’ quality through “intangible cultural heritage enters the community” activities. China Literary Artists, (6), 175–177.

Cite this article

Cao,S. (2025). A bibliometric study of intangible cultural heritage and community research. Advances in Humanities Research,12(2),1-11.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yan, W. (2024). Progress, hotspots, and trends in Chinese popular science journal research: A visualization analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map. Chinese Journal of Science and Technology Periodicals, 35(02), 163-170.

[2]. Yi, K. (2024). A literature-based review of museum experience design research: A bibliometric analysis. Packaging Engineering, 45(20), 272-284. https://doi.org/10.19554/j.cnki.1001-3563.2024.20.025

[3]. Tang, L. (2024). A visual analysis of research on ideological and political education in university English courses: A statistical analysis of CNKI literature from 2018 to 2023. Journal of Wuzhou University, 34(01), 90-99.

[4]. Liu, L. (2018). Research on the intangible cultural heritage of Bailu Ancient Village in the context of the post-industrial era (Master’s thesis). Gan Nan Normal University.

[5]. Huang, S., & Chen, W. (2024). Research on visual culture innovation in the digital dissemination of intangible cultural heritage. Cultural Exchange between China and Foreign Countries, (10), 106-108.

[6]. Yan, W., & Wang, J. (2025). Twenty years of rural communication research in China: Hotspots, evolution, and outlook — A visualization analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map. Southeast Communication, (01), 44-49. https://doi.org/10.13556/j.cnki.dncb.cn35-1274/j.2025.01.010

[7]. Peng, J. (2024). Research on the development of adult education courses for traditional craftsmanship intangible cultural heritage in communities (Master’s thesis). Sichuan Normal University. https://doi.org/10.27347/d.cnki.gssdu.2024.001453

[8]. Sun, J., & Yan, H. (2024). Using “community” as a method: Cultural heritage paths from the perspectives of sociology and anthropology. Southeast Culture, (06), 6-12.

[9]. Peng, M. (2025). From expert-led to community participation: The formation of public folklore in the United States and the “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Folklore Studies, (01), 62-74+157. https://doi.org/10.13370/j.cnki.fs.2025.01.004

[10]. Li, S. (2024). Research on the community-based inheritance of intangible cultural heritage: A case study of Gupo Song. Journal of Yangtze University (Social Science Edition), 47(06), 46-50.

[11]. Chen, X. (2024). Research on library strategies for community education and promotion in the protection of local cultural heritage. Media Forum, 7(14), 110-113.

[12]. Zhu, H., Wen, Y., & Zhang, H. (2024). Current status, hotspots, and trends in international deep leisure research: A knowledge map analysis based on the Web of Science core database (1982–2023). In Proceedings of the 1st National Outdoor Adventure and Leisure Sports High-Quality Development Seminar, 2nd National “Leisure Sports” National First-Class Undergraduate Program Construction Seminar, and 2nd Capital University Leisure Sports Academic Paper Report Conference (p. 15). Beijing Sport University, Sports Leisure and Tourism College. https://doi.org/10.26914/c.cnkihy.2024.014307

[13]. Xu, D., & Liu, Z. (2023). A review of the current status of Chinese foreign language research from the perspective of “new liberal arts”: A visual analysis based on CiteSpace knowledge map (2018–2022). Journal of Guizhou Normal University, 39(2), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.13391/j.cnki.issn.1674-7798.2023.02.011

[14]. Tian, J. (2024). The protection and inheritance of intangible cultural heritage from a community perspective. China Ethnic Expo, (8), 26–28.

[15]. Pu, Y. (2021). A knowledge map analysis of research dynamics in hospital party building. Gansu Medical Journal, 40(4), 362–364+370. https://doi.org/10.15975/j.cnki.gsyy.2021.04.025

[16]. Zhang, J. (2024). Practical exploration of the role of intangible cultural heritage in urban community construction. Journal of Jingdezhen College, 39(2), 1–6.

[17]. Yang, H. (2024). Initial exploration of the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage in online virtual communities. Cultural Heritage, (2), 9–16.

[18]. Zhou, H. (2024). Discussion on the integration of intangible cultural heritage into community cultural construction. China Ethnic Expo, (4), 61–63.

[19]. Yang, L. H. (2023). “Bringing the community’s voice to the forefront”: Multiple practice models of intangible cultural heritage protection and community participation. Journal of Yunnan Normal University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 55(6), 45–55.

[20]. Zhang, M. F. (2023). Community education’s role in protecting intangible cultural heritage in ethnic regions of China. Journal of Qiqihar University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), (8), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.13971/j.cnki.cn23-1435/c.2023.08.013

[21]. He, T. T. (2023). Research on rural cultural heritage protection strategies under the concept of community museums: A case study of Shuyi Village in Changsha, Hunan Province. Village Committee Director, (6), 137–140.

[22]. Ju, Y. Y., & Cheng, L. (2023). The formation mechanism of heritage responsibility behavior in tourism communities at cultural heritage sites: Based on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Journal of Natural Resources, 38(5), 1135–1149.

[23]. Wang, Q. C. (2023). Listening to the voices of heritage owners (Doctoral dissertation). Guangxi University for Nationalities. https://doi.org/10.27035/d.cnki.ggxmc.2023.000235

[24]. Li, L. Y. (2023). Research on the reconstruction of community education inheritance paths for intangible cultural heritage: A case study of the Mosukun of the Oroqen nationality. Heilongjiang Ethnic Journal, (2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.16415/j.cnki.23-1021/c.2023.02.021

[25]. Shi, J. D. (2023). Inheritance paths of intangible cultural heritage in cultural ecological protection areas: From the perspective of residents’ community cultural participation. China Ethnic Expo, (3), 72–74.

[26]. Gu, C. X. (2023). Inheritance and aesthetic education practices of cultural heritage in “community scenes”. Cultural Education Materials, (3), 30–33.

[27]. Feng, L., & Zhao, J. W. (2022). Lived co-construction: Intangible cultural heritage protection practices in community museums. Northwest Ethnic Studies, (4), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.16486/j.cnki.62-1035/d.20220823.001

[28]. Li, F. (2022). Research on improving citizens’ quality through “intangible cultural heritage enters the community” activities. China Literary Artists, (6), 175–177.