1. Introduction

According to G. R. F. Ferrari, Plato did not have a complete theory of “Eros.” Rather, Plato employed the accepted theories of desire to serve his own philosophical goals [1] (p. 248) — namely, to use philosophy to educate people to seek personal growth and the progress of the polis. Although this theory is not fully developed, we can still outline its basic framework. How is growth and progress sought? In the Symposium, it is through the pursuit of eternal beauty, which exists only in the realm of Ideas. In the general interpretation, Plato’s division of the world is usually understood as two: the realm of Ideas and the realm of phenomena. However, this view neglects the connection between the two realms, which is precisely linked by the Ladder of Love. Figuratively speaking, Plato’s education aims for people to start from the phenomenal world and climb the Ladder of Love upward toward the world of Ideas. Here, two theoretical frameworks emerge: one is Plato’s doctrine of separation, and the other is the Ladder of Love within this dual-world structure. This paper will focus on the Ladder of Love, while the doctrine of separation between the phenomenal world and the realm of Ideas will mainly serve as the background.

So, why discuss the Symposium today? The key lies in its important supplementation of Plato’s educational thought and method: introducing “desire” into education, transforming education from mere rational or saintly admonition into guidance that truly resonates with human experience and social-humanistic emotions. This can be glimpsed through the two concepts of “intellect” and “mystery”. Generally, philosophers discussing this topic consider two opposing concepts — reason and madness [2]. In this paper, “reason” is narrowed down to “intellect,” while “madness” is expanded to “mystery”. The former is to avoid forming two conflicting concepts as in previous interpretations; in the Symposium, it is essential to emphasize that these two factors are harmoniously unified, to the extent that “intellect” can be said to be unified under “mystery”, which is a distinctive feature of this dialogue. Furthermore, “intellect” compared to “reason” carries a stronger connotation of a state or condition, emphasizing the state itself rather than the faculty of reason. This can be seen in the character of Alcibiades, whose words and actions reveal Plato’s attitude — an emphasis on action. Applied to the Ladder of Love, this means continuously climbing upward and exercising one’s personal ability. Desire drives us to pursue beauty; what matters is not the cognition itself but the action of pursuing. The latter is because Plato’s discourse (at least in the Symposium) does not merely reflect madness; using the broader term “mystery” is more appropriate. Within the realm of mystery, intellect, madness, and other elements can be directly integrated without needing external concepts. Next, we will examine how these two aspects are manifested.

At the very beginning of the dialogue, there are multiple layers of discourse curtains [3] (172A–174B). The first layer is the conversation between Apollodorus and his friends; the next layer is the dialogue between Apollodorus and Glaucon; and only in the deepest layer does Apollodorus relay the words of Aristodemus to present the details of the Symposium. Regarding this, Chen Siyi offers a slightly different interpretative perspective in Philosophical Education and Its Failure: Alcibiades’ Discourse on Desire in the Symposium. He points out that Socrates’ speech exerts a certain sacred attraction on Apollodorus and Aristodemus, turning them into his followers, and even the entire dialogue has been preserved and transmitted by these fervent followers [4]. Under this multiple-layered concealment, Plato successfully places the discussion of desire under a veil of mystery. Furthermore, Socrates deepens this concealment by primarily recounting his dialogue with Diotima (although Mr. Chen Siyi verifies that this figure likely did not exist, this does not affect our understanding that Plato intended to make the dialogue more mysterious, or rather, it is precisely the nonexistence of this person that adds a mysterious aura to the most exquisite discourse on desire in the Symposium) [5] (p. 173) [3] (201D). Diotima’s discussion of desire employs the term “Highest Mysteries” [6] (210A), a word richly imbued with mystical connotations, to denote the secret teachings of desire. Moreover, Diotima herself is a priestess, a figure who governs the mystical connection between humans and gods. It is precisely this series of arrangements that draws our attention to the mysterious aspect inherent in the education of desire.

Of course, we must also pay attention to the intellectual element contained in this dialogue, which remains an unchanging position in Plato’s educational philosophy, and its manifestation in the text is particularly evident. For example, at the very beginning, Eryximachus proposes not to drink excessively and even dismisses the flute-girls [3] (176D–176E). Because of this, during the delivery of the six encomia, everyone is able to maintain a clear and intellective state in their inquiry into desire. Even if this restraint is somewhat pathological, and even though the first five encomia appear rather rough, this process of inquiry depends on intellect to gradually heal this pathology and to polish this roughness. The process of the Symposium also exemplifies the characteristic of Platonic dialogue to deepen progressively layer by layer, allowing the exploration of desire to go deeper. Moreover, the different applications of rational faculties reflect different levels of intellect, which also manifest varied influences along the three paths of desire’s teaching. Here, the predominance of intellectual factors mainly concerns the first path—that is, the initiation of the philosopher into the society.

2. The first path: the philosophic initiate

This path begins with Phaedrus and ends with Socrates’ private questioning of Agathon, presenting a typical Platonic [7] (pp. 13–29, 62–82) educational model: it emphasizes intellect over mystery, values inquiry and reflection on truth, and stresses the relationship between the individual and the polis.

Those who embark on this path must first address the question of motivation — or, in other words, how we turn toward the Ladder of Love — and further consider what constitutes a good way to enter it. Ferrari’s view, mentioned earlier, implicitly contains this idea. After all, Plato starts from generally accepted theories about desire, which also explains why the first five speakers in the Symposium deliver their encomia before Socrates speaks later. Specifically, this motivation has two aspects: external and internal.

The external motivation is represented by Phaedrus. Eryximachus mentions that Phaedrus often complains that no one praises Eros, the ancient and great god, which leads everyone to deliver encomia to pass the time [3] (177A–177B). This can be interpreted as Phaedrus being the awakener of desire, that is, the initiator of the education. In Platonic education, such an initiator often appears; the most typical example is the figure in The Republic who escapes from the cave and then returns — the one who sees the light [6] (515C). This also reflects the suddenness and mysterious driving force. However, in the Symposium, Phaedrus is not the one who returns to the cave to tell his fellow citizens the truth; rather, he is more like the one who suddenly frees the prisoner. The “freeing” at the scene of the Symposium draws attention to the power of the neglected god of love and guides people onto the Ladder of Love. It can be said that the initiator occupies an important position at the start of education; without Phaedrus’ passionate complaint, there would be no extensive encomia in the Symposium — that is, no conscious inquiry into desire. Placed within the framework of the theory of Ideas, the initiator is the trigger that causes the soul to turn away from the phenomenal world and toward the realm of Ideas. In the education of desire, the initiator likewise triggers a series of educational acts, turning desire from a natural state into a conscious one (although this conscious state may not be fully suitable for desire).

However, according to Ferrari’s interpretation, the Symposium is rooted in a problematic belief related to Phaedrus — the issue lies in that complaint. But this is acceptable because Phaedrus plays an important role as the initiator on the first path. Therefore, we can pay less attention to this flawed starting point of “complaint”, especially since this problem will be resolved by Socrates and Diotima later. The key problem with problematic belief is also related to Eryximachus [1] (pp. 249–250). His approach causes an internal motivational crisis at the starting point, namely impure motivation: on one hand, his proposal does not seem to express a heartfelt respect for the god of love nor an immersion in the beauty of desire, but rather a need to “discuss materials” and “pass the time” [3] (177D); on the other hand, regarding drinking, he insists on moderation for the sake of self-control (to avoid the troubles of drunkenness). How to resolve this internal issue is the difficulty of the starting point, but it will also be addressed later. Thus, on one side, Phaedrus directs desire together with a sense of shame straight toward polis politics, neglecting desire itself. On the other side, it is not Eryximachus but Pausanias who points out a flaw in the lover’s education of the beloved — only the beloved pursues virtue, while the lover pursues satisfaction of desire. Consequently, whether the beloved can maintain reverence for virtue after entering polis politics becomes questionable. Of course, Mr. Chen Siyi also believes these problems can be resolved by Socrates [5] (pp. 165–168).

After completing this turn, we can formally embark on the first path. For ease of exposition, we can divide the first six encomia into two groups, separated by Aristophanes’ hiccup [3] (185D)—the only occasion in the dialogue where the enforced order of speakers changes. The first group consists of Phaedrus, Pausanias, and Eryximachus; the second group includes Aristophanes, Agathon, and Socrates. The main difference between these two groups is that the first demands a distinction between good and bad love (though this is not explicit in Phaedrus), while the latter does not [1] (p. 250). This division more clearly shows how the inquiry into Eros progresses step by step and is effectively integrated in the second path. Additionally, Aristophanes’ hiccup underscores his identity as a comic playwright. Plato uses this device to create a comedic effect that effectively relieves the tension and concentration of the participants and readers caused by the lengthy speeches of the previous two speakers. It also resonates with the later tragic theme of Alcibiades and Socrates’ love, as well as Socrates’ final teaching in the Symposium: “Socrates wants to compel them to admit that the same person can write both comedy and tragedy” (emphasizing the unity of comedy and tragedy) [3] (223D). Eryximachus’ treatment of Aristophanes also highlights his identity as a physician. This gives us an opportunity to clarify the identities of the participants, mainly their professional roles: Phaedrus can be regarded as a sophist (he is a follower and admirer of the sophist Hippias; since little information is available about Phaedrus, here he is simply treated as a sophist for convenience of discussion) [8] (p.157); Pausanias is the only significant participant in the Symposium whose identity remains uncertain except that he is an Athenian and Agathon’s lover [8] (p.174); Eryximachus is a physician; Aristophanes is a comic playwright; Agathon is a tragic playwright; Socrates is a philosopher; Alcibiades is a politician and military leader. Besides these, there are two others: Aristodemus, who is a witness and narrator but does not deliver a speech, so his profession is not considered here; and Diotima, a priestess who appears only in Socrates’ narration. Later, we will see that the identities of the participants influence the entire Ladder of Love.

Firstly, the first group — a sophist, an obscure Athenian, and a physician — are unified under one theme: they almost entirely immerse themselves in intellect. They excel in and enjoy using their intellective faculties to think and solve problems, and they are highly concerned with polis politics.

Phaedrus interprets love through the lens of shame [3] (178B–180C). He discusses Eros together with polis politics, especially the matter of war related to the survival of the city-state, focusing on the political consequences of desire [5] (pp. 165–166).

Pausanias builds upon Phaedrus — although Ferrari distinguishes the two, he tends to see them as sharing the same expectations for love, both uniformly praising Eros. He suggests that Phaedrus merely overlooks the contrast between them. This article opposes that view, because subsequent encomiasts also praise Eros and show acceptance of the prevailing homosexual customs, which makes it impossible to distinguish two groups otherwise. Thus, treating Phaedrus as a preliminary groundwork is more appropriate [1] (p.251). Pausanias emphasizes careful differentiation between different kinds of Eros and further explains the correct union of lover and beloved — merging the love of adolescent boys with the pursuit of knowledge [3] (180D–185C). Pausanias’ encomium thus leads to his recognition of the political-educational function of desire. However, he neither corrects the genuinely mistaken bad belief nor criticizes the problematic social reality described earlier. This represents a dangerous educational stance toward political figures and social customs in the polis, which Socrates must correct by reinterpreting Eros.

After the position swap, Eryximachus also distinguishes types of Eros, but from the perspective of a physician, dividing love into “healthy love” and “pathological love.” Our task is to eliminate the pathological love to restore bodily balance. When he subsequently applies the harmony and rhythm of love to life, he approaches it from the standpoint of nature’s cosmos. Although both types of love manifest as harmonious rhythms, the melodies they express are completely different, and it is necessary to examine which kind of love aligns with the principle of “reverence for Heaven and fear of the gods”. Clearly, the physician represents a natural-philosophical view, yet in his final argument, he especially emphasizes the role of “sacrificial rites and divinatory ceremonies” in preserving and healing love. Along with his prior exhortations toward temperance and the joint initiation of the dialogue, we can see a further subtlety in their identities—Plato is employing and expanding the scientific and religious customs of his time to better serve a higher philosophy, akin to the philosophization of medicine [7] (pp. 89–119). However, such a natural-philosophical explanation does not fully apply to Eros, for love is more intrinsically rooted in human society and human nature itself.

Then, in the second group, we encounter two dramatists (one tragedian, one comedian—who, after Alcibiades’ intrusion, remain the most sober at the drinking party second only to Socrates) and a philosopher. At this stage, the proportion of people’s states has shifted; although intellective elements still dominate, a more mystical inquiry into truth gradually gains greater space.

Aristophanes again displays his talent as a comic playwright, cleverly enlivening the Symposium’s atmosphere. Before delivering his encomium, he deliberately asks: “Why must we endure that loud, weirdly itchy sneezing fit before our bodies return to normal?” [3] (189A). Clearly, this is a satire of the first group’s loud and bizarre speeches, which exhausted everyone; only at his turn do the encomia become normal. Using the myth of the spherical humans, Aristophanes directly overturns the first group’s distinction between different kinds of love. He defines Eros as the yearning and pursuit of wholeness; the desire to return to unity is the original expression of love. Under the hope of love, humans pursue their beloved to form a whole, which constitutes human happiness. Beyond the pursuit of wholeness, there is another requirement: reverence for the gods. Humans were originally separated because they presumptuously challenged the gods; only by revering and loving the gods can one experience the grace of Eros and thus restore unity [3] (189A–193E). This is precisely another key turning point that Aristophanes introduces. He makes a relatively effective attempt to reconcile reason and mystery, intellectively exploring the truth of Eros while addressing human belonging (a sense of belonging that Alcibiades notably lacks). This is no longer merely a political domain, because in Aristophanes’ theory, incompleteness is human nature, making this fully a domain of life. Herein lies a profound interpretation of the “mystical” state in the Ladder of Love.

Following Aristophanes is Agathon, who delivers a speech widely regarded as a painstakingly elaborate but ultimately superficial praise of Eros [3] (194E–197E). Ironically, the host of this Symposium is none other than Agathon himself, freshly crowned champion of the dramatic contest. Nonetheless, we can discern a particular contribution from Agathon: his argumentation is notably clear and serves as a model for Socrates’ subsequent discourse. Agathon states, “Whatever one praises, there is only one correct method: first explain what the object of praise is, then explain the effects it produces; so, when praising the god of love, one must first say what he is, then what benefits he bestows” [3] (197A).

Socrates then begins by ironically criticizing all the preceding speakers: “Our method seems to be that everyone only makes the appearance of praising the god of love, without truly praising him. Because of this, it seems to me that you have all exerted great effort attributing everything to the god of love, saying he is such and such and produces such effects, to show that he is the most beautiful and excellent; but this is only so to the ignorant, not to those with discernment. Thus, this is a splendid encomium, but when I promised to praise the god of love, I did not know it was to be done this way. Therefore, that was a verbal promise, not a heartfelt one. Please allow me to take my leave—I cannot give such a praise, for I simply do not know how. However, if you permit me to speak honestly in my own way, not to compete in rhetoric and become a laughingstock, I would be willing to try” [3] (198E–199B). Socrates here directly targets the flawed belief—that is, the impure motive—and criticizes the method of inquiry into Eros employed by the previous five speakers. He then initiates a dialectic with Agathon—a dialogue that adopts Agathon’s own methodological framework and roughly parallels the teachings of Diotima. One might say Agathon’s contribution lies in providing the schema for the first path up the Ladder of Love. This also relates to the earlier point about Plato borrowing widely accepted theories of love to serve his philosophical aims. Through this dialogue, Socrates overturns the simplistic attribution of beauty and goodness to Eros by Agathon and others, clarifying that love is the desire for what is lacking. The god of love only pursues beauty and goodness, so love itself is neither beautiful nor good. This insight plunges both participants and readers into a mix of enlightenment and new perplexity.

Looking back, this has been a rather long and winding path, but it is progressive and deepens step by step, aligning with common modes of thought. However, Plato’s journey along the first path of intellective inquiry into Eros temporarily ends here. Next, we must proceed to the second path.

3. The second path: the lesser mysteries of love

The second path is generally considered a higher level than the first. Philosophical initiates, having encountered setbacks in their intellective pursuit of Eros along the first path, move on to a different extreme in the second path—one that is almost entirely immersed in mysticism. This stage does not reject reason outright; rather, the proportion of reason is smaller. The reason is that, compared to the intellective element in the first path, the intellect here is of a higher order—one that can yield to mystery to better enable Eros to function. The second path can be seen as a transition between the first path and the deep mysteries of love; philosophical initiates at this stage shift their original conscious state back into a natural state.

The priestess Diotima and the philosopher Socrates clarify through inquiry that the god of love “is a great daimon... intermediate between gods and mortals” [3] (202E). They further explain that only gods are wise and thus do not seek wisdom, while the ignorant, being unaware of their own ignorance, have no intention to pursue wisdom. Therefore, the god of love becomes the philosopher, because only the philosopher truly pursues wisdom (the lover of wisdom). This effectively turns the entire theme of the Symposium from a praise of Eros to a praise of the philosopher. Moreover, this also responds to Aristophanes’ revelation from a different angle: although we are indeed pursuing something lost, Aristophanes mistakenly thought we were seeking our other half, whereas in fact, we are pursuing the Good [1] (p.253). Here the essence of love is clarified—that love longs for eternal possession of what is good [3] (206A). This narrative also answers the issue raised by the first group on the first path: love is always good, and there is no need to distinguish between good love and bad love. Diotima further explains that the apparent distinctions arise simply because people use proper names for the whole name—some types of love are called love, while others are given different names [3] (205B–205D). After clarifying what the god of love is, the next step is to specify what function love has. Based on the essence of love, as long as it points to what is good, it undoubtedly brings happiness to humans. The greatest value of the teaching on Eros is to make people happy [3] (205A).

Next, Socrates asks how we should engage in the activities of love. Diotima answers, “Love is not aimed at beautiful things themselves... its purpose lies in giving birth and procreation in beautiful things” [3] (206D). People achieve immortality through procreation. Generally, love aroused by Eros leads one to love beautiful bodies and thus achieve immortality through offspring. But ultimately, one must transcend physical procreation and engage in the procreation of the soul. The procreation of the soul cultivates virtue, and “among these virtues, the greatest and most beautiful are those that arrange the affairs of the state and the household, called clarity and justice” [3] (209A). Thus, on the second path, love is once again linked to the politics of the polis. We can describe this higher-level relationship as “immortality through lineage” and “immortality through politics” [9].

Basically, the second path has also reached its conclusion. Methodologically, it largely aligns with the approaches of the previous five speakers; however, the key lies in the fact that the second path provides a gradual ascending framework. The mystical state here is our natural state (mystical, internal—distinct from the natural analogy of pursuing harmony in Eryximachus’s encomium). This state requires no explicit articulation; the crucial point is that we dwell within it. Guided naturally by Eros, we inevitably act accordingly. This explains why this study places great emphasis on the issue of “state”: only when one is truly engaged in doing something can one enter a definite state, or conversely, the manifestation of a definite state indicates that a person is indeed doing something. So, what are these people doing? They are following Plato’s teaching, climbing the ladder of love. Two things can be established here. First, Phaedrus’s initiating role is actually effective only for those on the first path; those on the second path do not require initiation. They only need to act according to their own eros and certainly need not go to the trouble of lavishly praising eros. After all, obeying the mysterious summons of eros and enabling one’s soul to give birth smoothly is the greatest praise and reward for eros. From this, the second thing can be affirmed: the concept of the “mystical” must here be deepened and clarified. “Mystical” is essentially human life and human selfhood. “Reason” functions merely as a necessary instrumental state within our political life in the polis (such as communication, making political decisions, etc.), embodying the exercise of intellective capacity. This exercise varies in quality but is always situated within the mystical whole. When eros manifests in ancient Greek life, it is undoubtedly manifested in the political life of the polis—but this is still insufficient, for what truly matters to humans is to turn toward the human self.

Before formally entering the deep mysteries of love, I must add another facet of the second path: the second path need not necessarily follow the first path. Some people can enter the second path directly without passing through the first. Here the second path does not serve as a transitional phase but rather as a preparatory stage for the deep mysteries of love. They naturally enter the second path under the stimulation of eros and thus proceed into the deep mysteries of love. In the Symposium, there is such a figure: Alcibiades. However, Alcibiades does not delve into the deep mysteries of love. His intrusion is the most dramatically effective part of the Symposium as a “tragicomedy”.

In principle, the Symposium should have ended after Socrates relayed Diotima’s teaching, at most concluding with a brief debate between him and Aristophanes. Alcibiades’s uninvited, seemingly off-topic encomium thus appears odd. But we should note that although Socrates’s teaching is basically concluded aside from some details, Plato’s teaching is not. Alcibiades’s intrusion vividly manifests Plato’s stylistic signature. Alcibiades appears here as a special kind of reflector (interestingly, Alcibiades is often cast as an opponent of philosophy). He symbolizes Plato’s reflection on his teacher Socrates’s educational philosophy. We can also incorporate the scholarly notion of “enthusiasm” (mania) here—this mania is, of course, unified within the mystical.

Alcibiades’ encomium also undergoes a transformation: it shifts from praising Eros to praising Socrates [3] (214D–222B). In his encomium, Plato reveals multiple misunderstandings that Alcibiades has about Socrates. Throughout, Alcibiades is overshadowed by political eros; although he admires Socrates’ teachings, once he realizes he cannot obtain virtues from Socrates that serve political life, he willingly distances himself from him. Moreover, Alcibiades himself embodies a strong element of mania (enthusiasm). He enters intoxicated, wearing a wreath of ivy and violets—symbols of Dionysus in Greek mythology, who is represented by a garland of ivy, grapevines, and grape clusters. (Additionally, as Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, shed tears that turned into violets.) After completing his encomium, Alcibiades brings a large group of revelers who cause everyone to abandon earlier moderation and drink to excess [3] (223B). However, Socrates also bears some responsibility in this misunderstanding. His education adopts a perspective superior to political life, which can breed arrogance towards politics. As a political figure, Alcibiades is naturally hurt by this perceived arrogance. Socrates also favors teaching through sarcasm—Liu Xiaofeng notes that the term hubris (often translated as arrogance, mockery, or even bullying) appears nine times in the Symposium and is almost exclusively applied to Socrates himself [8] (p.170). Additionally, the inversion of their roles as lover and beloved, combined with Alcibiades’ repeated frustrations [4], culminates in the tragic nature of their eros relationship. Socrates’ reprimands of Alcibiades [3] (214D, 214E, 222D) thus mark the failure of his educational efforts.

Here we see that although Alcibiades naturally embodies eros more intensely than the philosophical initiates, he remains stuck at this level. He can never progress into the deep mysteries of love. On a personal level, he misapplies his intellective faculties, which manifest as crude and ineffective in serving the mystical. We often interpret Alcibiades as a failure of philosophical education [4], but in fact, it is Socrates who fails. Plato places Alcibiades’ intrusion here to reflect on Socratic pedagogy and to improve it, ultimately shaping his own educational method. Although Alcibiades may have misunderstood Socrates’ famous maxim “The unexamined life is not worth living”, interpreting it as a criticism of his own life and thus devaluing it—and while the maxim emphasizes continuous “examination” rather than “action”, which does not align with Alcibiades’ practical political and military focus—Plato knowingly employs this misunderstanding. After all, it represents a common misconception among polis citizens. Therefore, while Plato continues to champion “examination”, he also emphasizes the “living” aspect of life. For example, Plato’s stylistic shift is evident in the deep mysteries of love teachings: Socrates rarely uses the dialectic method there and instead allows Diotima to speak uninterruptedly. This marks a change, as Plato, through Alcibiades’ misunderstanding, doubts that endless philosophical inquiry without political action is adequate [4]. Accordingly, in some places Plato provides direct answers (e.g., in Book VI of The Republic, after the initial guidance, Socrates himself outlines the political structure of the ideal city, while Glaucon’s few interjections are minor and mostly confirmatory), facilitating practical action. This article further argues that Plato places strong emphasis on the phenomenal world, which is at least the only level of the ladder of love accessible to ordinary people. In this sense, it is justifiable to call it the “real world”.

Thus, although Alcibiades can be situated on the second path, his role resembles more that of an outsider to the ladder of love. Alcibiades would certainly never admit to being within such philosophical eros teachings; rather, he serves better as a contrast and reflection on eros instruction. At this point, we can set this reflector aside and focus our attention on the deep mysteries of love.

4. Unified in the mysteries of love

Ultimately, the first two paths converge in the mysteries of love. However, since certain errors on the first path must be corrected along the second, it is more accurate to say that in the initial stages, the first two paths run in parallel; then the first path merges into the second, which at this point plays a transitional role leading to the mysteries of love. At this stage, eros transcends the level of political life and turns directly toward itself, focusing on the individual’s personal growth and perfection. The mysteries of love are also a state of complete immersion in the mystical, but compared to the second path, reason here harmonizes more naturally within the mystical, playing a functional role within this harmonious unity. This can be seen in the mysteries of love’s simultaneously natural yet rigorously ordered dialectical pattern. In short, the mysteries of love reconcile the first and second paths. A minor question arises here: how do those who enter the second path directly, bypassing the first, attain this more harmonious reason? The answer lies in the mystical itself. On one hand, such individuals experience an enlightening transformation in their pursuit of immortality, akin to the soul’s immediate intuitive turn toward the mysteries of love; on the other hand, some are inspired by initiators like Diotima on the second path to make this turn. Of course, there are also those like Alcibiades who reject this turning.

At this stage, the narrator is only the priestess. The mysteries of love manifest through strict order: one must first pursue the beauty of individual bodies from youth, then turn to the beauty of bodily types, next place greater value on the beauty of the soul than on bodily beauty, and then discover the beauty that pervades all things, reaching the beauty of knowledge. Finally, the person discovers the one knowledge—the knowledge of beauty itself. At the conclusion of the doctrine of love, people contemplate beauty itself, with all particular beauties partaking in it. Only thus is the virtue we nurture no mere shadow but true virtue. However, mortals alone cannot achieve this; it is only possible with the help of the god of love [3] (210A–212A).

Here, Phaedrus employs the displacement of attention to explain the dynamics of the ladder of love: the beauty of the body inspires a person to produce a beautiful discourse. As previously mentioned, the individual continuously shifts the object of pursuit, generating a new beautiful discourse at each stage. Finally, at the level of knowledge, the discourse produced is philosophical discourse [1] (pp. 256–259). At each stage, one is stimulated, contemplates, and generates, repeating the same process in the next stage. Meanwhile, Mr. Chen Siyi offers another interpretation: the ladder of love is essentially a ladder of contemplation, and the entire process is one of seeing, with only the highest stage being the place where we should “generate” [9]. Regarding intellectual inspiration, this article tends toward the former interpretation, as it explains the ladder of love based on eros. Although eros essentially pursues eternal beauty and immortality, it is important that the mysteries of love emphasize order. Each stage’s eros impulse should not be denied; rather, it is necessary to preserve the results of each stage through generation, which also contains an element of immortality. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, we have long surpassed the stage of distinguishing whether eros is good or bad; eros is always directed toward the good. However, the latter interpretation arguably aligns better with Socrates. Here a supplementary argument is that from Socrates’ attitude, he always aims only at eternal beauty, and therefore naturally abandons non-eternal beauty. This choice is related to a statement by Socrates himself: “Truth cannot be refuted; refuting Socrates is not difficult” [3] (201C). Nonetheless, whatever the description, this remains a description of states. How exactly such a transformation occurs is beyond inquiry [1] (p. 257), for it is mystical—something we must do under the influence of eros’s power.

After resolving the issue of motivation, we ascend orderly toward the eternal beauty above. Yet because the world of Ideas is difficult to grasp, we must also ask: is what lies above truly the world of Ideas? This insight is chiefly drawn from Ruby Blondell [7] (pp. 184–225), who examines where Socrates should be placed on the ladder of love. Generally, Socrates appears as a seeker of the highest good. He himself often emphasizes his own ignorance and, in the Symposium, describes himself (the philosopher) as impoverished, striving to possess eternal beauty. On the other hand, Socrates’ complete teachings and noble character make him seem almost mythical; Alcibiades even uses the term “statue” to describe Socrates’ inner qualities [3] (216E–217A). So, is Socrates on the ladder of love, or is he in the world of Ideas? Blondell’s conclusion is that Plato places Socrates at every step of the ladder of love. This clever approach reveals that the world of Ideas and the sensible world are unified.

For the city-state’s inhabitants, if one is to compare the importance of the world of Ideas and the sensible world, the conclusion is that both are vital, from two perspectives: first, the world of Ideas greatly benefits the transformation of the sensible world, serving as an essential method; second, Plato’s theoretical aim is ultimately directed at the sensible world, with the world of Ideas being the best method he could conceive to achieve this goal. All theories built on this framework must serve the transformation of the sensible world. Accordingly, Socrates says: “Respect all things related to love, do so passionately, and arouse others to do the same” [3] (212B). In the Symposium, other guides and inspirers appear, such as Phaedrus and Diotima, whose existence signifies an unwavering commitment to the sensible world and the effort to live a better life within it. Moreover, the distinction between the two worlds is not so great; there is some distance, but the world of Ideas is inherent within the sensible world. In this sense, the mystical is the sensible world itself, which is thereby confirmed, and reason corresponds to the world of Ideas. This allows us not only to manage the relationship between the mystical and reason, but also the relationships among the elements within the mystical. The mystical is the tangible, perceptible world we live in; reason is merely the intrinsic state of this world. The ladder of love naturally arises within this mystical realm, constructed by reason and the mystical. Such a structure does not conflict with the ladder’s upward movement; the ascent is cyclical. As people climb the ladder of love toward higher realms of Ideas, they simultaneously look back upon the sensible world and continually examine and transform it from higher perspectives.

Then why don’t we simply act directly, rather than discuss these theories of eros? Isn’t this also using eros to guide toward something (education) without immersing directly in eros itself? In this sense, the ladder of love resembles Wittgenstein’s approach: “If someone understands me, then after using my propositions—stepping on them—he will climb beyond them and see that they are senseless. (One must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after climbing it)” [10] (6.54). This dialogue functions as a necessary yet ultimately useless ladder to help us ascend.

5. Conclusion

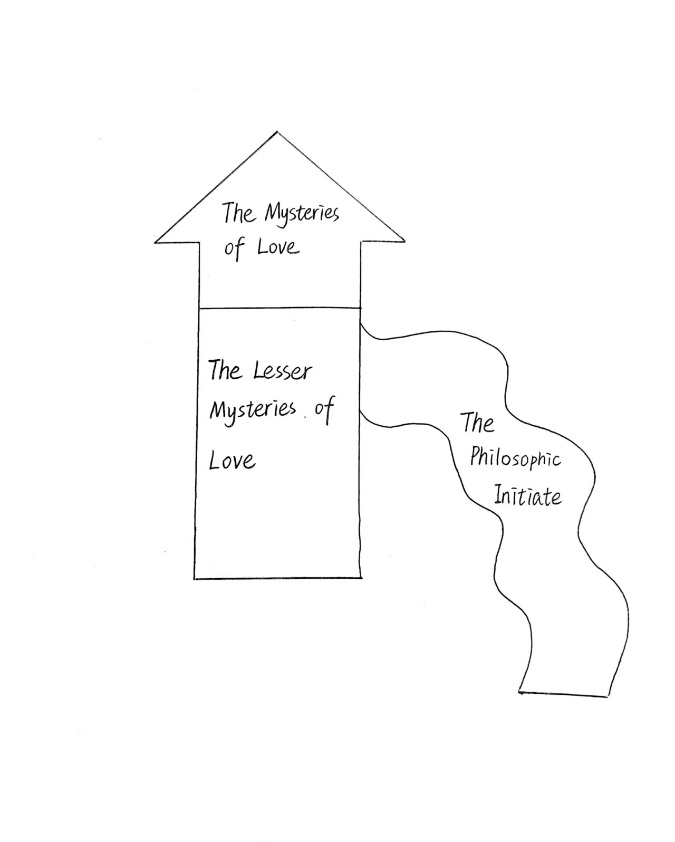

Overall, the entire teaching of eros unfolds through three paths. Philosophical initiates typically start from a lower point and, after a winding process of exploration, enter the second path—the minor mystery of love. However, some can start directly from the second path, and because they skillfully harness the power of eros to place themselves in a mystical state, they are closer to the major mystery of love. Thus, those who enter directly from the second path begin at a higher point, making their process of receiving the teaching of eros smoother. Ultimately, regardless of which path one takes, as long as they accept the teaching of eros, they gradually ascend into the major mystery of love, the third path (see Figure 1). Through these three paths, we have progressively clarified the concepts of the mystical and reason and used these two state-based concepts to interpret the ladder of love. Although the ladder of love appears in Symposium only within the major mystery of love, the two parallel and converging paths prior to it are indispensable preparations. Moreover, both paths exhibit a splendid interplay of reason and the mystical, so we still place them within the scope of the ladder of love. In this sense, this paper has somewhat expanded the scope of the ladder of love. Beyond this inquiry, we also saw the figure of Alcibiades as a reflective agent. Plato here more explicitly expresses his attitude toward the sensible world, reflecting on the tension between philosophical education and political life. Finally, we further examined the apex of the ladder of love and concluded that the world of Ideas is inherent within the sensible world. The interaction between these two worlds manifests the function of eros and establishes the possibility of human growth under eros’ influence.

To conclude this investigation, we may pose a small question: Is the person climbing the ladder of love lonely? This question concerns the lived experience of each climber. This paper’s answer is negative, a point visible in Socrates. Compared to Alcibiades—who valued political life but also defected from it—Socrates arguably ensures his non-loneliness precisely through belonging politically only to Athens as a city-state. Athens symbolizes our origin and this sensible world. We climb the ladder of love, pursuing eternal and immortal beauty, yet we still live in our human world. We continue to love people and love our lifeworld. (Existentialists seem to echo this call for the lifeworld made over two millennia ago, though more directly without necessarily passing through the world of Ideas.) We still return to the cave because it is our origin and the unique particularity retained in our hearts. After all, although Socrates was judged by the Athens he loved deeply, it is hard to say he died in lonely misery. Especially when recalling his past, he saw that he not only enjoyed the continual pursuit of wisdom but also the teaching and growth of Athenian youths, many delightful conversations such as symposia, and in his final moments, the presence of disciples and friends filling the room.

References

[1]. Kraut, R. (2006). The Cambridge companion to Plato. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Wang, J. (2023). A brief exploration of Plato’s “madness of reason. ”JinguWenchuang, (24), 70–74.

[3]. Plato. (2019). Collected dialogues of Plato (W. Taiqing, Trans. ). Beijing:Commercial Press. (Original work published date unknown)

[4]. Chen, S. (2022). Philosophical education and its failure: Alcibiades’ discourse on eros in Symposium.Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (02), 5–14.

[5]. Liang, Z. (2022). Twenty lectures on Plato’s dialogues. Beijing: Commercial Press.

[6]. Plato. (1997). Complete works of Plato (J. M. Cooper, Ed. ). Hackett Publishing Company.

[7]. Leiser, J. , et al. (Eds. ), & Liang, Z. , et al. (Trans. ). (2018). The ladder of love: Interpretation and echoes of Plato’s Symposium. Beijing: Renmin University Press.

[8]. Liu, X. (2015). The four books of Plato. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

[9]. Chen, S. (2020). “Begetting” or “viewing”? — Eros and immortality in Plato’s Symposium.Philosophy Gate, 21(02), 1–22.

[10]. Wittgenstein, L. (2013). Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Beijing: Commercial Press. (Original work published 1921)

Cite this article

Mei,J. (2025). Climbing the ladder of love between intellect and mystery: a study on the educational views in Plato’s Symposium. Advances in Humanities Research,12(3),45-52.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kraut, R. (2006). The Cambridge companion to Plato. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Wang, J. (2023). A brief exploration of Plato’s “madness of reason. ”JinguWenchuang, (24), 70–74.

[3]. Plato. (2019). Collected dialogues of Plato (W. Taiqing, Trans. ). Beijing:Commercial Press. (Original work published date unknown)

[4]. Chen, S. (2022). Philosophical education and its failure: Alcibiades’ discourse on eros in Symposium.Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (02), 5–14.

[5]. Liang, Z. (2022). Twenty lectures on Plato’s dialogues. Beijing: Commercial Press.

[6]. Plato. (1997). Complete works of Plato (J. M. Cooper, Ed. ). Hackett Publishing Company.

[7]. Leiser, J. , et al. (Eds. ), & Liang, Z. , et al. (Trans. ). (2018). The ladder of love: Interpretation and echoes of Plato’s Symposium. Beijing: Renmin University Press.

[8]. Liu, X. (2015). The four books of Plato. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

[9]. Chen, S. (2020). “Begetting” or “viewing”? — Eros and immortality in Plato’s Symposium.Philosophy Gate, 21(02), 1–22.

[10]. Wittgenstein, L. (2013). Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Beijing: Commercial Press. (Original work published 1921)