1 Introduction

The global higher education landscape has increasingly recognized universities as pivotal institutions for fostering talent, as evidenced by the growing imperative to enhance lecturers' professional growth and development. Specifically, the development of educators plays a crucial role in the establishment of top-tier research universities. Only the continuous improvement of teachers' level can ensure a high quality of education and teaching. Chen [10] shows that lecturers who actively participate in a variety of activities foster stronger bonds between the faculty and the lecturer involved. Kusters et al. [30] emphasize the crucial role of training as a fundamental component for both the continuous professional development of lecturers and university progress. Some authors, such as collaborating with colleagues, establishing knowledge management, participating in workshops, and mentoring services, propose that some models can improve lecturers’ professional development [10,19,30,51]. Additionally, business school lecturers often lack practical experience and struggle to navigate the intricacies of real-world business scenarios [11]. Lecturers endeavour to enhance the visibility of their research by publishing in journals with high-impact factors, while simultaneously imposing quantifiable performance targets and accountability pressures on lecturers affiliated with the business school [1,21].

Despite this, massive studies focus on lecturers’ professional development in the past while making minimal contributions to the business school in research universities in the 21st century. Soliman et al. [50] and Brouwer et al. [8] suggested that Lecturers foster their professional development through the implementation of innovative pedagogical approaches. Gribling and Duberley [21] argue that the influence of institutional reputation profoundly shapes the trajectory of individual careers, compelling faculty members to expedite their professional development. To improve the expertise and competencies of lecturers, it is advisable to give priority to the release of scholarly journals, provide opportunities for instructors to obtain specialized qualifications and practical experience, and seamlessly incorporate professional growth within the online teaching platform offered by the business school [9,21,29,39].

In fact, to enhance the progress and advancement of lecturers, research universities are implementing an extensive initiative for professional enrichment. The primary objective is not centered on expanding their magnitude, but rather specifically aimed at improving the research excellence of the lecturer’s professional development. According to El [18], lecturers’ endeavor to acquire and apply novel knowledge and skills to enhance their effectiveness in teaching. The competence and self-efficacy of lecturers are pivotal factors in the professional development of contemporary society [2,40,48]. Gong et al. [20] demonstrate that lecturers frequently articulate a demand for professional development in research, encompassing the acquisition of knowledge regarding scholarly endeavors. Additionally, Yuan & Gao [60] emphasize that international professional development is widely acknowledged as an effective means to augment lecturers' intercultural competence and effectiveness. In practical applications, lecturers can pursue diverse professional development opportunities through the resources provided by research-oriented universities.

This article addresses the research gaps in career development for lecturers at research universities and business schools, focusing on their effective utilization of abundant institutional resources to integrate scientific research with teaching courses, thereby achieving a harmonious integration of theory and practice for career advancement. This action is undertaken to achieve two research goals. These objectives are:

1) To explore the lecturer’s professional development in business school

2) To build a model of lecturer’s professional development in the business school of research universities in the 21st century

2 Literature Review

2.1. Effective Lecturer Professional Development

2.1.1. Teacher Professional Development

Gong et al. [20] define professional development as encompassing structured upskilling opportunities, including formal courses. Most importantly, teacher professional development encompasses the self-educational activities undertaken by educators. It involves participating in diverse further education opportunities related to the field of education to continually enhance knowledge, skills, and attitudes about fundamental principles, teaching methodologies, administrative practices, teacher collaboration, and service commitment, thereby fostering ongoing promotion and development [61]. Teacher Professional Development (TPD) programs can be comprehensively delineated as initiatives designed to cultivate an individual's proficiency, understanding, knowledge, and other attributes pertinent to the role of a teacher [41]. Teacher Professional Development is characterized as the systematic process aimed at enhancing a teacher's knowledge, attitudes, skills, and personal attributes to effectively fulfil their professional duties [25,35].

On the other hand, teacher professional development contains the learning process for educators, encompassing how they acquire new knowledge, develop learning strategies, and utilize this knowledge in practical settings to improve student educational outcomes [26,41]. Professional learning for teachers is characterized by the development of teacher knowledge, resulting in a transformative shift in practice that yields enhanced student learning outcomes [26]. Opfer and Pedder [39] claim that the improvement of student learning requires a pathway that includes the introduction of more effective professional learning activities for educators within educational institutions. In this context, 'effective' activities are those that yield positive changes for both teachers and their followers. Consequently, the process of teacher professional learning is intricate. Teachers acquire knowledge through participation in diverse courses and engage in reflection on their teaching within the school environment. Furthermore, active learning is recognized as a promising best practice in professional development. They observe and reflect on colleagues' teaching, fostering cooperation among peers [41,56]. The core of these initiatives lies in acknowledging that the emphasis of professional development is on teachers' acquisition of knowledge and understanding of how to effectively apply it to foster their students’ progress [3]. Sancar et al. [47] state that various measures have been taken to promote such circumstances, urging teacher colleges and other educational institutions engaged in teacher education to develop and enrich teachers' current knowledge and methods, leading to better academic results for students and higher school standards.

2.1.2. Lecturer Professional Development

In higher education institutions, lecturers play a primary role as essential personnel. They serve as representatives of their institutions and significantly contribute to shaping the quality of the education and learning processes. On the other hand, they are catalysts for innovation in pedagogical methodologies, fostering an environment that encourages active student engagement [50]. According to Brouwer et al. [8], a lecturer's instructional approach not only shapes the course design but also significantly impacts the learning process in the context of their professional development. Furthermore, lecturers operate within complex and unpredictable contexts, they are not readily available for final solutions and clear instructions for action. Many lecturers are not formally trained as educators, leading to a tendency for their knowledge of pedagogy to be inconsistent [19,35].

Collaborative and collegial behaviors are also integral to the professional development of lecturers. Workshops and short courses traditionally serve as cornerstones in centrally provided professional development programs [19]. Chen [10] suggested that repeated exchanges of the same lecturer to a specific institution fostered stronger connections between the faculty and the participating lecturer. Collaborating with colleagues under conducive conditions is considered an essential requirement for delivering engaging and effective education [19,30]. Professional development has the potential to empower lecturers to take increased responsibility for planning and actively engaging in their continuous learning. Additionally, El [18] shows that it facilitates reflective discussions with colleagues about their teaching practices.

On the other hand, individual approaches are also important for a lecturer’s professional development. It is recommended to contextualize the training within a comprehensive professional development program that is tailored to local, institutional, and personal requirements [35]. Due to pedagogical training courses in higher education have demonstrated success in fostering a more student-centered approach among younger lecturers. They suggest extending these courses to early career academics [2,8]. In addition, Training efforts for lecturers extend beyond universities, with instances of organizations and bodies endeavoring to establish certified training for subject teachers [2,30]. According to Alhassan [2], these courses are typically generic, often taking the form of intensive short refresher courses for lecturers. The exchange experience within training was found to contribute to professional development by fostering a deeper and broader understanding of lecturers [10]. Kusters et al. [30] found that this underscores the significance of training as a pivotal element for both continuing professional development and school advancement.

2.1.3. Effective Lecturer Professional Development

Strategies aimed at enhancing lecturer professional development may involve a variety of methods. Firstly, collaborating with colleagues emerges as a prevalent avenue for sharing experiences and ideas, fostering an essential exchange that enriches reflective practices [10,19,30]. According to Tigelaar [52], peer meetings provide a platform for participants to discuss and enhance their teaching methodologies. For instance, lecturers can gain novel insights by participating in diverse courses, reflecting on their instructional approaches within the school context, and engaging in collaborative efforts to observe and reflect on their colleagues' teaching practices [41].

Secondly, Lecturers' professional development encompasses their learning process, skill acquisition, and the practical application of knowledge to support pupil learning [3,26,41]. Kusters et al. [30]maintain that the establishment of a knowledge management mechanism facilitates the provision of essential knowledge for lecturers' professional development, enhancing their professional self-confidence and abilities. Concurrently, it promotes enhanced knowledge sharing within lecturer professional communities, contributing to the development of knowledge and cultures within school organizations [61].

Thirdly, Chia [11] revealed that workshops constitute the most prevalent form of TPD programs. Workshops display diverse formats, including those lacking supplementary elements, those integrating instructional designs, and those backed by collaborative development of instructional designs with professional communities [51]. Within these workshops, lecturers hone their conversation skills, thereby augmenting their professional development [52].

Fourthly, besides workshops, mentoring serves as an additional model for lecturer professional development. emphasizes expertise in particular fields, knowledge of effective teaching methods, research-based strategies for inquiry, and cooperative efforts [19,51]. Lecturers expect to receive extra assistance for teaching, such as the provision of top-notch professional development opportunities, resources to improve their knowledge of effective teaching methods and exemplary approaches, guidance, and support from the district regarding educational initiatives, and allocated time for collaborative endeavours with fellow educators [25]. According to El [18], mentoring is characterized as a linear knowledge transfer process from an experienced lecturer to a less experienced counterpart, facilitated through discussions and reflective practices. This entails teachers receiving professional development support from esteemed expert colleagues.

2.2. Current Lecturer Professional Development in Business School

2.2.1. The Characteristics of Business School

Higher education greatly relies on the significant contribution of business schools, shaping current and future leaders poised to impact the world significantly [14,24]. Liu [14] argues that as the managerial class has risen, business schools have evolved into prestigious institutions focused on achieving corporate success and generating wealth. Within these schools, pedagogical knowledge and education support units are often influenced by positivistic scholarship, which prioritizes technological interventions for improving measurable metrics. Consequently, business schools serve as training grounds for talent propelling a significant portion of management roles [14,29].

Three characteristics of a business school are unique. First, Cooper et al. [13] suggest that accreditation holds greater value for schools competing for resources against other accredited institutions. Accreditation programs are required to adhere to rigorous standards for instructor qualifications and maintain robust scholarly output. Moreover, it imposes stringent requirements for collecting high-quality assessment data, in addition to instructor qualifications and scholarly output [13,58]. One notable accreditation is the Triple Crown, which represents the attainment of all three major international accreditation: AACSB in the USA, EQUIS in Europe, and AMBA in the UK [14,24,38].

Next, due to their focus on a curriculum centred around specific disciplines that align with the research interests and ambitions of scholars, business schools further strengthen the intellectual priorities of academia [11]. According to Krishna and Orhun [29], a bulletin is released by the Registrar of the Business School, which outlines the designated schedules for certain fundamental courses. Kociatkiewicz et al. [28] comment that the curriculum of the business school is seen as upholding capitalist relationships. However, business schools are often absorbed in academic rigour, potentially neglecting practical relevance and, consequently, diminishing societal impact [44].

Finally, at the core of many business schools lie the fundamental components of research and education. There is significance in business schools emphasizing practical wisdom alongside providing scientific and technical expertise. Management education encompasses the development of applied sagacity, surpassing the mere dissemination of factual scientific information, proficiencies, and methodologies [44,49]. It has been suggested that a significant portion of the research conducted in business schools focuses excessively on scientific rigour while overlooking practical applicability, commonly referred to as the gap between rigour and relevance [44].

2.2.2. Lecturer Professional Development in Business School

Business schools mainly focus on fundamental and specialized subjects, yet frequently fail to provide practical curriculum that effectively connect theoretical knowledge with real-life scenarios. Chia [11] found that business schools frequently face criticism for their failure to sufficiently equip graduates with the essential abilities of creativity, adaptability, and problem-solving skills required to effectively handle intricate real-life business scenarios. Combining practical management experience with a strong academic background increases credibility by effectively connecting theory and real-world application [49]. Programs with a focus on skills aim to educate students on the mechanics of running their businesses. Therefore, lecturers in business schools emphasizing practical wisdom should possess firsthand experience in managing a corporation or organization.

In addition, the discernible outcomes for lecturers within business schools are a result of the impact that competition and reputational imperatives have on human resources policies and practices. The management of academic careers significantly impacts the attractiveness of such lecturers, thereby influencing institutions' ability to attract, retain top talent, and maintain a competitive edge [21]. According to Abzug [1], business schools are increasingly promoting the benefits of corporate universities and commercial business schools, shifting from cooperation to rivalry and placing greater emphasis on measurable performance goals and lecturer accountability. As an illustration, business schools strategically recruit lecturers with publications in highly ranked journals to enhance their research visibility. Lecturers also continue to depend on business schools for career management and development [21]. Opfer & Pedder [39] described that the effectiveness of augmenting lecturers' knowledge and skills through professional development is heightened when it forms a comprehensive program of lecturer learning by the business school.

2.2.3. Current Lecturer Professional Development in Business School

Prioritizing the publication of academic journals, offering opportunities for lecturers to acquire subject-specific qualifications and experience, and seamlessly integrating professional development into the online teaching environment of the business school is more likely to develop the expertise and skills of lecturers [9,21,29,39].

In the first place, universities urged lecturers to submit their research papers to internationally recognized English-language journals. Because of journals are increasingly stringent in terms of lecturers' technical expertise, resulting in an escalation of the time required for paper crafting and revision [20]. Although professional development is a dual-faceted process, driven by both institutions and individuals, each business school competes for acceptance in a limited number of top journals [20,21]. Therefore, business schools prompt academics to engage in research, publish, and adjust their workloads, accordingly, leading to a continuous decline in lecturers' acceptance rates.

Then, lecturers swiftly adapted from traditional, in-person interaction-focused teaching methods to remote, technology-enabled content dissemination and virtual engagement platforms. The transition to online teaching presented notable obstacles for educators, including the need for instruction on utilizing digital classrooms effectively, determining ideal class length, and integrating formative evaluations into online teaching environments [9]. Depending on the lecturers' teaching styles, they have the option to incorporate various media into their lessons to engage students, including the customization of course materials for group study [12]. Mariam et al. [37] show that tasks such as marking students' attendance, collecting assignments, creating subject-specific quizzes, tests, and digital extracurricular exercises contribute to class engagement and can be efficiently managed through the tools provided by an eLearning platform.

2.3. Lecturer Professional Development in Universities of 21st Century

2.3.1. Lecturer Professional Development in Universities

When investigating knowledge management among university lecturers, it consistently demonstrates a strong correlation with the purpose, outcome, or destination of lecturer professional development [61]. This linkage exists because the efficacy of knowledge management directly impacts the quality of a lecturer’s professional development. Vereijken and van der Rijst [54] observe that university instructors utilize a comprehensive range of conceptualizations and expertise derived from their subject knowledge and pedagogical proficiency in the field of higher education instruction. El [18] argues that lecturers continuously gain and implement fresh expertise and abilities to improve their teaching effectiveness. As an example, it is recommended that instructors engage in ongoing professional growth activities to update, advance, and enhance both their instructional techniques and understanding of the subjects they teach [3]. Consequently, the imperative for lecturer professional development (LPD) involves updating subject knowledge and didactics [20].

On the other hand, Liang et al. [33] argue that lecturer educators should not merely serve as instructors transmitting knowledge and skills, but also engage in the study and reflection of teaching and learning. Lecturers research to meet academic demands, address frontline problems, and gain insights into teacher education. They address their LPD (Learning and Professional Development) needs by participating in specialised training and engaging in international communities of activities [3]. Engaging in International educational activities is widely recognized as a valuable approach to improve research-related abilities and instructional methodologies [20]. However, research demands are influenced by job requirements and performance pressures related to tenure, annual assessments, and career advancement, necessitating participants to produce research regardless of their workplace [33].

2.3.2. The Traits of Universities in the 21st Century

A university is a prestigious establishment of higher learning that possesses the necessary authorization to grant advanced degrees in three or more academic disciplines or areas of study [15]. Yang et al. [59] assert that a university comprises scholars and students forming a truth-seeking community. Universities, characterized by a teaching-oriented approach, strive to cultivate competent educators [33]. Denman [15] highlights the university's responsibility to disseminate and advance knowledge through scholarly endeavours and research in 21st-century universities. Furthermore, universities play a key role in fostering scientific and technological advancements. The scientific research conducted within a university entails a multifaceted process involving various inputs, internal procedures, and diverse outcomes [59].

Most importantly, the evolution of society has led to the expansion and standardization of the roles of colleges and universities. Specifically, faculty cultivation, scientific research, and societal service have emerged as the primary functions of current higher education institutions. Presently, these functions represent a global consensus within the higher education system [59]. In today's age of globalization, universities are acknowledged as crucial national resources. For example, in numerous countries, they serve as primary hubs for the domestic research base and have spearheaded the development of cross-disciplinary concepts [7].

Next, universities require instructors to improve their current proficiency, understanding, and abilities to adapt to the swiftly changing educational environments. Numerous universities across the globe have implemented institutional structures that enforce instructor involvement through various means. The fulfillment of specific criteria often determines contract extensions or advancements in academic ranks [48].

Finally, the complex and interrelated system of universities acts as the source of unique advantages valued by society, encompassing economic, social, cultural, and practical benefits [7]. According to Zhang et al. [61], higher education was anticipated to contribute to economic development, enhance the competitiveness of existing firms, and proactively foster university-led high-tech industries.

2.3.3. Lecturer Professional Development in Universities of the 21st Century

Lecturers and universities possess distinct objectives concerning professional development. Lecturers prioritize development initiatives that contribute to research, whereas the university emphasizes enhancing classroom teaching quality and student achievement [48]. The competency and self-efficacy of lecturers play a crucial role in professional development within contemporary society.

On the one hand, the competence of lecturers significantly impacts students' academic performance and the reputation of their affiliated institutions. Lecturers' responsibilities extend beyond knowledge transfer; they play a crucial role in supporting and preparing students to emerge as skilled professionals contributing to the nation. In this context, the competence of lecturers directly shapes that of their students. Lecturers are expected to serve as comprehensive resources, facilitating students in connecting theoretical aspects of subjects with current industrial practices [40]. Therefore, lecturers must enhance their professional competence, which plays a crucial role in the overall studying process.

On the other hand, self-efficacy pertains to an individual's confidence in their ability to navigate challenging situations and fulfil assigned responsibilities [5]. Bandura [4] studied that this task-specific belief governs decision-making, exertion, and perseverance in the presence of obstacles. The self-efficacy among lecturers is greatly impacted by the recognition they receive from students and colleagues, the formal education they obtain during their university studies, and their experiences within the academic institution [48]. Alhassan [2] asserts that research conducted on the enhancement of lecturers' skills in higher education has uncovered a multitude of advantages stemming from the correlation between professional development, positive self-efficacy, and the overall advancement and achievement of educators.

2.4. Lecturer Professional Development in Research Universities

2.4.1. The Characteristics of Research Universities

While research plays a critical role in any university, it does not necessarily constitute its most basic function in most higher education institutions. However, research universities offer a broad spectrum of degree-granting programs, spanning from bachelor's to PhD levels, and engage in extensive research activities [15]. The research conducted by universities not only establishes the framework for their educational role but also demonstrates the high cost-effectiveness of these institutions, especially in the realm of basic research [7]. Additionally, to attain world-class status, universities should fundamentally embody the characteristics of research institutions with a commitment to "universalism". This necessitates an international orientation across faculty, students, research endeavours, and teaching materials [32]. Liang et al. [33] think that research universities typically hold top positions in both national and international university rankings. They are recognized for providing nationally and internationally acclaimed programs, serving as exemplars for other teacher education institutions. First-class research-oriented universities aspire to develop lectures into researchers.

Besides, universities, especially comprehensive ones, possess a distinctive capacity to encompass a wide range of knowledge among all human institutions. As a result, they hold the potential to swiftly reorganize and combine their expertise in innovative manners to tackle both the growing number of interdisciplinary issues that are gaining significance and explore fresh avenues of comprehension unexpectedly [7]. In addition, personnel departments and research units in universities prioritize a lecturer's paper publications, their role in hosting scientific research projects, and their award status. The recruitment processes in universities often emphasize the introduction of talent, particularly focusing on the demonstration of significant scientific research achievements during the application process. Subsequently, after undergoing examination and throughout the assessment period, these talents also undergo a title appraisal [32].

2.4.2. The Current Trend of Research University Development

The evolving trend manifests in four key aspects. First, research universities are urged to adopt a more proactive role as catalysts for innovation. Their pivotal role in innovation lies in cultivating human capital across bachelor's, master's, and doctoral levels [7]. Saavedra & Opfer [46] found that the development of creativity necessitates structured and intentional efforts from lecturers and can be imparted through disciplinary approaches. Lecturers teaching directly about the creative process and factors contributing to creative development further enhance this endeavour. As a result, they contribute to creating an environment conducive to innovation, especially when linked with globally competitive research and producing outstanding graduates.

Second, research universities enhance the intellectual, social, and cultural assets of a region to attract knowledge-intensive businesses, promote entrepreneurial endeavours, and forge collaborative partnerships with businesses to establish interactive mechanisms [7]. Furthermore, it is imperative to enhance the collaboration between universities and businesses while promoting the seamless integration of academia and industry [32].

Third, Li & Xu [32] argued that international exchange and cooperation constitute integral components of the comprehensive strength of research universities, with a focus on achieving world-class status that necessitates global integration. Simultaneously, there is a need to broaden access to high-quality overseas educational resources through diverse channels, enhance the scale and proficiency of overseas student enrolment, engage in sophisticated international cultural exchanges across various formats, and foster exceptional talents affiliated with international organizations in diverse domains [7,32].

At last, in advancing the development of research universities, numerous institutions leverage their strengths in scientific research, dismantling technological monopolies and addressing the nation's significant requirements. Therefore, they play a crucial role in major national scientific research initiatives, subsequently enhancing their scientific research capabilities and standards [7,32].

2.4.3. Lecturer Professional Development in Research Universities

Research emerged as the most frequently cited category of professional development needs for lecturers, encompassing the acquisition of knowledge about research and academic activities. Frequently cited approaches to fulfil research-related requirements encompass engaging in professional development programs, acquiring knowledge from academic conferences, talks, and seminars conducted by experts, exploring opportunities for studying or visiting scholars overseas, and embarking on a PhD [20]. According to Liang et al. [33], participants affiliated with research universities tended to define themselves as pragmatic researchers, emphasizing the practical value of research.

Furthermore, the utilization of overseas professional development emerges as a widespread approach to enhance lecturers' intercultural competence and effectiveness. Inclusive within specific lecturer education and professional development schemes are opportunities for temporary overseas study or cultural immersion. These endeavours have demonstrated their ability to enrich lecturers' understanding of diversity and intercultural knowledge [60]. Besides, a secondary objective for lecturers engaging in professional development programs is the enhancement of their teaching skills. Exposure to overseas teaching environments, diverse teaching methodologies, and comparative learning stimulate the development and transformation of participants' professional identity, fostering an expansion of their pedagogical thinking [33,60].

3. Method

Content analysis functions as a methodical and unbiased approach to research, enabling accurate deductions from verbal, visual, or written data to describe and measure specific occurrences [16]. As stated by White & Marsh [57], content analysis is a research technique that allows for consistent and reliable deductions about the contextual usage of texts. Recognizing the importance of language in human cognition lies at the core of the value attributed to content analysis as a research methodology [17]. The objective of this method is to enhance knowledge and comprehension of the phenomena being studied through a structured process of coding and categorizing text to reveal patterns and themes [43]. The primary goal of content analysis is to enhance the interpretive accuracy of findings by establishing connections between categories and the specific context or setting in which the data was generated. White & Marsh [57] demonstrate that inference plays a crucial role in content analysis. Researchers utilize analytical constructs, also known as rules of inference, to bridge the gap between textual information and responses to research inquiries. The basic steps include a) Sources of data, b) Data collection, c) Coding, d) Categories, e) Analysis of content, and f) Interpretation of results.

To begin, the article is comprehensively indexed in the Social Sciences Citation Index. For instance, the chosen article focused on lecturer professional development and relevant literature was searched through the Social Sciences Citation Index. Within this search, it was discovered that there are variations and objectives in lecturer professional development across different institutions. Consequently, the author extracted and organized the concept of lecturer professional development within our article.

Secondly, this article compiles 48 articles sourced from the Social Sciences Citation Index. The first part focuses on extracting effective professional development for lecturers. The second part provides an overview of current professional development practices for lecturers in business schools. The third and fourth parts examine the contemporary landscape of lecturer professional development in both business schools and universities of the 21st century.

Eventually, code and categorize the coding. When coding this article, the author selected relevant literature to organize and summarize it into concise words, sentences, or paragraphs. For instance, Liang et al. [33] found that research emerged as the most frequently cited category of professional development needs for lecturers. Their study revealed that participants affiliated with research universities tended to identify themselves as pragmatic researchers who prioritize the practical value of their work. Therefore, the author has condensed the research-related content from their literature into a comprehensive paragraph for further elaboration.

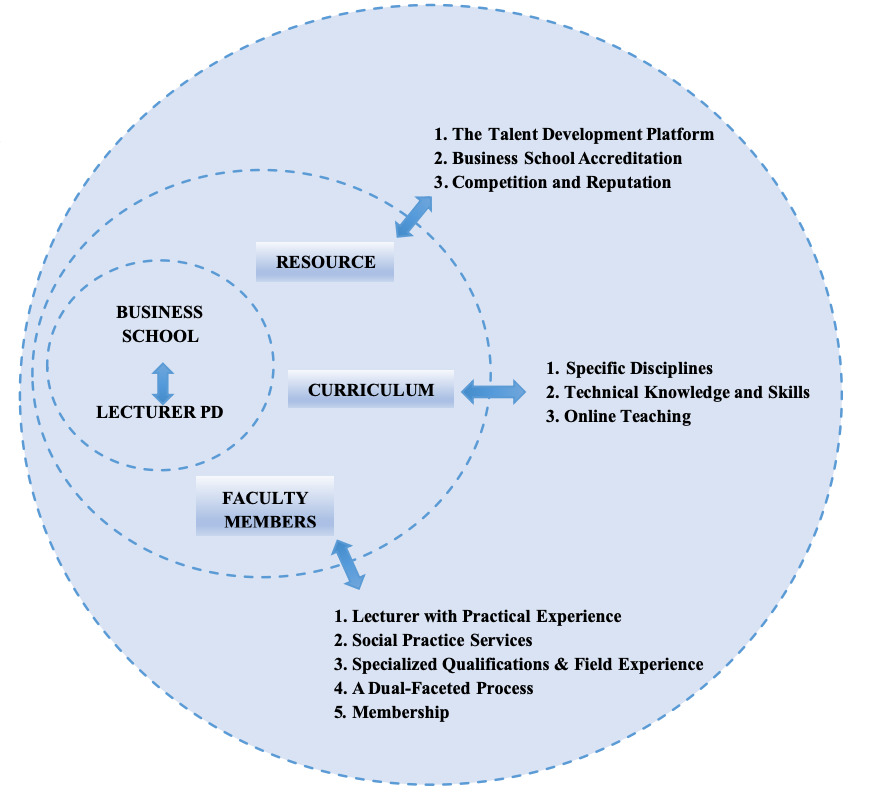

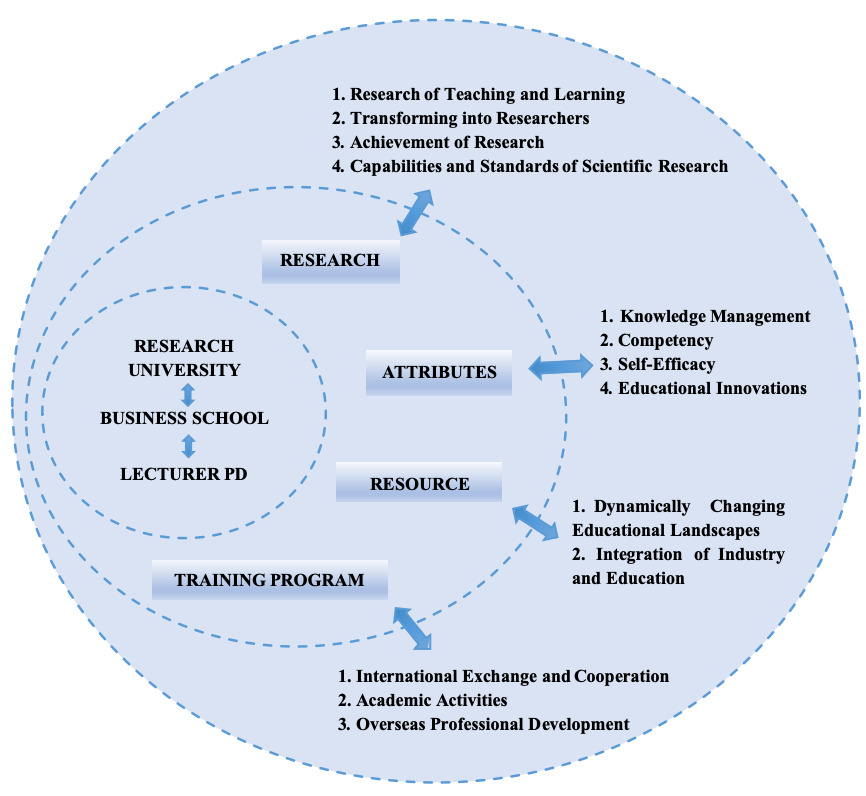

Through the collection and collation of relevant literature from SSCI, two graphs are constructed. The core of Figure 1 depicts the interrelationship between business schools and lecturers, while the middle layer highlights three pathways for lecturer career development within business schools. The outermost layer provides detailed insights into the specific content encompassed by these three channels of lecturer development. Similarly, Figure 2 focuses on the relationship among lecturers, business schools, and research universities at its core. The middle layer illustrates four distinct trajectories through which lecturers can advance their careers, while the outermost layer delves into specific details about each trajectory. Ultimately, a comprehensive analysis is conducted to examine every facet associated with lecturer career development.

For example, the first research question pertains to lecturers’ professional development in a business school. In the preliminary investigation concerning the professional advancement of instructors in business school, the author undertook a thorough examination of the strategies utilized to augment their proficiency. Initially, the author’s primary focus involved delving into literature about business school through the utilization of the Social Sciences Citation Index. During this exploration, the author encountered an article entitled "The Relevance and Impact of Business Schools: In Search of a Holistic View," offering a comprehensive examination of extant literature concerning the significance and influence of business schools. Subsequently, the author extracted and systematized pivotal attributes linked to business school from this source for integration into research. Furthermore, upon scrutinizing the publication by Cooper et al. [13], it became evident that accreditation of business schools emerged as a prominent feature. To delve deeper into this aspect within the framework of a business school, the researcher consolidated findings into a dedicated paragraph elucidating accreditation.

4. Discussion and Analysis

4.1. For Objective One: To Explore the Lecturer’s Professional Development in Business School.

4.1.1. Resources of Business Schools

1) The Talent Development Platform. Business schools function as platforms for nurturing talent essential for driving a substantial segment of managerial positions. For example, these investments have been directed towards improving the quality standards of teacher education programs; refining the efficacy of novice teacher initiation programs; expanding avenues for teachers to pursue master’s or even PhD degrees; and augmenting salary grades for educators, thereby amplifying growth prospects within the teaching profession [45]. Lecturers rely on the resources provided by business schools for managing and developing their careers.

2) Business School Accreditation. The accreditation of a business school profoundly affects both its academic standing and the reputation of the university it is affiliated with. Achieving accreditation of the Triple Crown signifies exceptional qualifications and authoritative recognition. Accreditation will enhance the resources of the school. Meanwhile, the clear connection between the mission and strategies of the university and those of the business school implies that business school accreditation is intricately linked to both the academic standing of the business school and the reputation of its host university [21,38].

3) Competition and Reputation. The influence of competition and reputation in business schools significantly affects the appeal of lecturers. The field of business relies on the qualification standards established by accrediting bodies to conduct assessments and ensure quality assurance in business schools. Thus, the significance of performance excellence in business school in higher education is self-evident. The decision of a business school to pursue accreditation hinges on the significance of competition, economic benefits, and lecturer [13].

4.1.2. The Curriculum of Business School

1) Specific Disciplines. Business schools underscore the importance of a curriculum rooted in specific disciplines. The principal responsibility of a business school is to enrich students’ learning encounters by imparting focused knowledge and equipping them with requisite skills. The mandatory syllabus includes basic modules covering accounting, economics in business, effective communication in a business setting, financial management, marketing principles, organizational behavior, statistics, as well as strategic planning [28].

2) Technical Knowledge and Skills. In addition, lecturers predominantly emphasize technical knowledge and skills, although employers and markets increasingly seek graduates with behavioural competencies alongside requisite knowledge and skills, necessitating educators to surpass conventional pedagogical paradigms and customary curricular confines. They must augment the curriculum with practical content to empower students with additional career-related skills pivotal for their professional lives post-graduation.

3) Online Teaching. Lecturers underwent a rapid transition from traditional classrooms to online teaching in the business school. Online teaching holds benefits for both students and teachers alike. This mode of teaching allows for enhanced flexibility, heightened collaboration, improved time management, personalized education, and reduced expenses. Online learning employs various eLearning tools. These tools provide invaluable assistance to both educators and students. Acquiring new technology for teaching a group of students may pose challenges; however, it presents an opportunity for skill enhancement. Technical literacy consistently benefits educators in the long term [37].

4.1.3. The Faculty Members of Business School

1) Lecturer with Practical Experience. Lecturers at business schools who emphasize practical experience should possess firsthand experience in managing a business or organization. Many business schools also hire adjunct professors with practical industry experience who can provide real-world insights to complement the theoretical knowledge taught in the classroom.

2) Social Practice Services. Business schools not only provide scientific and technical expertise but also offer social practice services. In addition to teaching and conducting research, lecturers actively engage students in societal service initiatives. Consequently, they are more inclined towards incorporating practical assignments into their courses. Practical assignments are an intriguing method for supplementing course content and enhancing student learning [22]. By integrating academic expertise with practical experience, lecturers aim to offer a comprehensive education that prepares students for diverse career paths in the business world.

3) Specialized Qualifications and Field Experience. Lecturers possess specialized subject-related qualifications and pertinent field experience required for instructing students in business schools. Business lecturers may come from backgrounds in accounting, marketing, and human resources. In addition to their graduate and doctoral degrees, they are likely to possess specialized work experience in a field related to business administration. With the increasing emphasis on data-driven and analytical approaches in the field of marketing, instructors for accountancy or marketing courses are anticipated to possess specialized subject-related qualifications and relevant field experience [6]. It is recognized that academic disciplines of this nature can be acquired through well-established and validated pedagogical methods. Consequently, there is a pressing need to recruit additional lecturers to enhance students' success in these fields [6,29].

4) A Dual-Faceted Process. Business schools facilitate a dual-faceted process wherein lecturers are encouraged to engage in research and publication while enhancing their professional development. For instance, business schools, driven by the imperatives of accreditation and rankings, allocate substantial funds to resident lecturers dedicated solely to research activities. Meanwhile, business schools assess lecturers based on a multitude of criteria, including teaching quality, innovation, engagement, institutional involvement, and managerial duties.

5) Membership. The core of most business schools lies in the fundamental pillars of faculty members. Common pedagogical approaches employed by lecturers encompass case studies, lectures, and assigned readings aimed at fostering students' critical thinking skills and their capacity to comprehend, interpret, and analyze information. Moreover, students frequently seek their lecturers for practical, specific, and experiential knowledge related to small business management issues [6,49].

Figure 1. Network of TPD in Business School

4.2. For Objective Two: To Build a Model of Lecturer’s Professional Development in Business Schools of Research Universities in the 21st Century.

4.2.1. Research

1) Research of Teaching and Learning. The lecturers’ professional development entails systematically exploring and critically analysing pedagogy and educational practices. Lecturers must employ pedagogical strategies to ensure a focused instructional approach in education. Specifically, university lecturers play a crucial role as agents of change, facilitating sustainable educational development in university teaching. In this context, the significance of teachers' knowledge and pedagogical skills is paramount.

2) Transforming into Researchers. In research universities, lecturers will gradually transition into researchers. Lecturers possess the capacity to cultivate impactful research within their scientific domain, generate intellectually stimulating inquiries, strike a harmonious balance between teaching and research endeavours, effectively disseminate the knowledge they produce across diverse communities, and proficiently mentor emerging researchers while seamlessly integrating them into the academic sphere.

3) Achievement of Research. Research universities provide state-of-the-art infrastructure to facilitate the research work of lecturers, ensuring they have access to adequate research grants. Consequently, the publication of an article in a prestigious journal by lecturers signifies acceptance and recognition from the global research community. Additionally, universities offer promotional incentives to researchers with publications in top-indexed journals.

4) Capabilities and Standards of Scientific Research. The scientific research capabilities of universities and colleges consistently furnish substantial support for the progress of national science and technology, consequently yielding a significant contribution to the augmentation of the country's high-tech capabilities [42].

4.2.2. Attributes

1) Knowledge Management. The integration of research into instruction at universities has considerable potential to foster a more profound comprehension of disciplinary knowledge. Refining the methods, strategies, or outcomes of lecturer professional development can concurrently advance and elevate the strategies, methods, or outcomes of university knowledge management [61].

2)Competency. To augment their professional competence, lecturers ought to endeavour to swiftly restructure and amalgamate their skills in inventive manners within research universities, so as to proficiently tackle the progressively crucial trans-disciplinary matters [7].

3) Self-Efficacy. The lecturer's professional development exerts a strong influence on individuals' positive self-efficacy, which refers to the belief in one's ability to successfully perform the required behaviours in work-related situations [45]. Klassen & Tze [27] demonstrate that the effectiveness of teachers plays a pivotal role in elucidating the variations observed in student achievement within any educational system. Regarding lecturers, self-efficacy has been found to bolster their perseverance in dealing with challenging students and exerts a noteworthy influence on their instructional practices, enthusiasm, commitment, and teaching behaviours.

4) Educational Innovations. Within the research university, lecturers assume a pivotal role as educational innovators, fostering an atmosphere of dynamic creativity that entices research-intensive companies and investments in an area. Consequently, this process catalyses innovation within indigenous businesses [7]. Research universities, by fostering extensive collaboration among educational institutions, businesses, and research organizations, significantly contribute to the integration of various fields and promote the creation of novel assets. This contribution, in turn, advances and establishes various investment opportunities.

4.2.3. Resources

1) Dynamically Changing Educational Landscapes. Universities mandate that instructors continuously enhance their existing expertise, knowledge, and skills to effectively navigate the dynamically evolving educational landscapes. Lecturers in the 21st century possess an accelerated vision towards the future, necessitating them to remain cognizant of emerging trends in technology, teaching styles, as well as issues and developments within education.

2) Integration of Industry and Education. Research universities play a crucial role in making substantial contributions to the intellectual, social, and cultural assets of a particular area. They actively foster the influx of knowledge-intensive businesses, stimulate entrepreneurial activities, and establish effective mechanisms of interaction by fostering collaborations with industries [7,32]. Valentín [53] showed that the primary impetus driving university researchers to employ in collaboration with industry resides in the fulfillment of the university's social function. Meanwhile, business executives place a high value on external collaboration owing to their constrained internal capacity for technological research.

4.2.4. Training Program

1) International Exchange and Cooperation. The responsibility of a research university encompasses nurturing talents with a global perspective, fostering collaborations with international universities, perpetually improving educational quality, and aspiring to attain world-class status. Enhancing the scientific research performance of local universities greatly relies on the pivotal catalysts provided by scientific research and knowledge exchange. Heightened international exchanges and collaborations serve to facilitate the cross-border flow of talents, augment the human capital of academic institutions, promote knowledge exchange and interaction among universities, and access international knowledge and technology, thereby amplifying the scientific research output of these institutions [42].

2) Academic Activities. Lecturer groups bolster their scientific research and international publishing capabilities by actively participating in global academic conferences, collaborating on research projects with prestigious universities worldwide, and nurturing exchanges within the international academic community. Through active engagement in global academic conferences, conducting extensive research, and exchanging ideas with esteemed international universities, along with proactive involvement in collaborative research initiatives on a global scale, our objective is to nurture the expansion of human capital within our educational institutions and enhance their capacity for innovation.

3) Overseas Professional Development. Participation in professional development programs abroad has the potential to cultivate a learning and working environment with a more global perspective for educators, concurrently serving to allure distinguished foreign universities and educational institutions as significant collaborators. Such endeavours empower research universities to assimilate and incorporate state-of-the-art teaching management methodologies and innovative talent development strategies globally, thereby fostering the nurturing of forward-looking individuals endowed with an international outlook and augmenting the collective quality of human capital.

Figure 2. Network of TPD in Business School in the 21st Century.

5. Conclusion

In the backdrop of the 21st-century knowledge economy, the global landscape is marked by fierce competition. Research universities act as strategic bastions in nurturing an innovative nation, capitalizing on their distinctive strengths to forge national scientific and technological prowess, and facilitating advanced self-sufficiency in science and technology. They play a pivotal role in propelling social development, with the professional growth of lecturers comprising a critical element of research endeavors within these establishments. This article has two primary objectives: first, to investigate the professional development of lecturers in business schools; second, to formulate a model for the lecturers’ professional development in business schools within research universities in the 21st century. This study utilizes content analysis methods to formulate a holistic model of lecturers' professional development, encapsulating two primary dimensions. First, it examines lecturers' professional advancement within business schools, where they utilize institutional resources and curriculum to augment their expertise. Faculty members of business schools play a crucial role in this process. Second, it introduces a model specifically designed for lecturers' professional development in business schools of research universities during the 21st century. This model integrates four critical components: research achievement, personal attributes, available resources, and an effective training program.

Previous research has predominantly focused on the professional development of teachers in non-higher education institutions, with limited investigation into specific organizations or institutions. Some scholars argue that lecturers' professional growth can be enhanced through various approaches, such as collaborating with colleagues, implementing knowledge management systems, engaging in workshops and training programs, and receiving mentoring services [10,19,30,51]. Lecturers in the 21st century no longer solely rely on individual capabilities to enhance their professional development. Instead, they can effectively advance their careers by fully leveraging the abundant resources provided by business schools and research universities, while integrating their attributes, goals, and experiences for personal growth. By participating in international training programs offered by research universities, lecturers not only broaden their global perspective but also gain valuable insights into project collaboration and academic activities. Ultimately, lecturers should strive to combine scientific research with teaching courses as a means of achieving a harmonious integration of theory and practice for career advancement.

The findings of this study have contributed to a more refined trajectory for future research and understanding of business schools in research universities, by pinpointing deficiencies within the existing body of literature. The limitation of this paper lies in its omission of quantitative research methods for data analysis and the absence of empirical evidence to support the proposed model. Future research should employ this model in educational institutions and design a questionnaire survey focused on the professional development of faculty members in business schools affiliated with research universities.

References

[1]. Abzug, R. (2022). Structural drivers and barriers to the strategic integration of sustainability in US B-schools. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(5), 986–1001. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe-10-2021-0433

[2]. Alhassan, A. (2021). Challenges and professional development needs of EMI lecturers in Omani Higher Education. SAGE Open, 11(4), 215824402110615. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061527

[3]. Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher Professional Development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

[4]. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986(23-28).

[5]. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

[6]. Bennett, R. (2006). Business lecturers’ perceptions of the nature of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 12(3), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550610667440

[7]. Boulton, G., & Lucas, C. (2011). What are universities for?. Chinese Science Bulletin, 56, 2506-2517. https://doi: 10.1007/s11434-011-4608-7

[8]. Brouwer, N., Joling, E., & Kaper, W. (2022). Effect of a person-centred, tailor-made, teaching practice-oriented training programme on continuous professional development of STEM lecturers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103848

[9]. Chauhan, S., Goyal, S., Bhardwaj, A. K., Sergi, B. S. (2021). Examining continuance intention in business schools with digital classroom methods during COVID-19: A comparative study of India and Italy. Behavior Information Technology, 41(8), 1596–1619. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2021.1892191

[10]. Chen, R. T. H. (2018). University lecturers’ experiences of teaching in English in an international classroom. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1527764

[11]. Chia, R. (1996). Teaching paradigm shifting in management education: University Business Schools and the entrepreneurial imagination. Journal of Management Studies, 33(4), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1996.tb00162.x

[12]. Choi, J.J., Robb, C. A., Mifli, M., & Zainuddin, Z. (2021). University students’ perception to online class delivery methods during the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus on hospitality education in Korea and Malaysia. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport Tourism Education, 29, 100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100336

[13]. Cooper, S., Parkes, C., & Blewitt, J. (2014). CAN accreditation help a leopard change its spots? Social accountability and stakeholder engagement in business schools. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(2), 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-07-2012-01062

[14]. Davies, J., Thomas, H., Cornuel, E., & Cremer, R. D. (2023). Leading a business school. Taylor & Francis Group.

[15]. Denman, B. (2009), What is a University in the 21st Century?. Higher Education Management and Policy, vol. 17(2),9-28. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v17-art8-en

[16]. Downe‐Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health care for women international, 13(3), 313-321.https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339209516006

[17]. Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the Content Analysis Literature in Organization Studies: Research Themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106289252

[18]. El, A. A. M. M. A. (2023). The role of educational initiatives in EFL teacher professional development: a study of teacher mentors’ perspectives. Heliyon, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13342

[19]. Ferman, T. (2002). Academic professional development practice: What lecturers find valuable. International Journal for Academic Development, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144032000071305

[20]. Gong, Y., MacPhail, A., Guberman, A. (2021). Professional learning and development needs of Chinese University-based Physical Education teacher educators. European Journal of Teacher Education, 46(1), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1892638

[21]. Gribling, M., Duberley, J. (2020). Global competitive pressures and career ecosystems: Contrasting the performance management systems in UK and French Business Schools. Personnel Review, 50(5), 1409–1425. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-05-2019-0250

[22]. ] Gujarathi, M. R., & McQuade, R. J. (2002). Service-learning in business schools: A case study in an intermediate accounting course. Journal of Education for Business, 77(3), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599063

[23]. Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

[24]. Hammond, K., Harmon, H., Webster, R., Rayburn, M. (2004). University Strategic Marketing Activities and Business School Performance. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500410568565

[25]. Huang, B., Jong, M. S. Y., Tu, Y. F., Hwang, G. J., Chai, C. S., & Jiang, M. Y. C. (2022). Trends and exemplary practices of STEM teacher professional development programs in K-12 contexts: A systematic review of empirical studies. Computers & Education, 104577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104577

[26]. King, F. (2013). Evaluating the impact of teacher professional development: An evidence-based framework. Professional Development in Education, 40(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.823099

[27]. Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

[28]. Kociatkiewicz, J., Kostera, M., Zueva, A. (2022). The ghost of capitalism: A guide to seeing, naming and exorcising the spectre haunting the business school. Management Learning, 53(2), 310–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505076211005810

[29]. Krishna, A., & Orhun, A. Y. (2021). Gender (still) matters in Business School. Journal of Marketing Research, 59(1), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243720972368

[30]. Kusters, M., van der Rijst, R., de Vetten, A., Admiraal, W. (2023). University lecturers as change agents: How do they perceive their professional agency? Teaching and Teacher Education, 127, 104097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104097

[31]. Lai, H.M., Hsiao, Y.L., Hsieh, P.J. (2018). The role of motivation, ability, and opportunity in university teachers’ continuance use intention for flipped teaching. Computers & Education, 124, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.013

[32]. Li, J., Xue, E., Li, J., & Xue, E. (2021). The policy analysis of creating world-class universities in China. Creating World-Class Universities in China: Ideas, Policies, and Efforts, 1-33.

[33]. Liang, J., Ell, F., Meissel, K. (2023). Who do they think they are? professional identity of Chinese University-based teacher educators. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2191814

[34]. Liu, H. (2022). Teaching for freedom, caring for ourselves. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(1–2), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2022.2131268

[35]. Loads, D. J. (2009). Putting ourselves in the picture: art workshops in the professional development of university lecturers. International Journal for Academic Development, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440802659452

[36]. Maor, D. (2006). Using reflective diagrams in professional development with university lecturers: A developmental tool in online teaching. The Internet and Higher Education, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.03.005

[37]. Mariam, S., Khawaja, K. F., Qaisar, M. N., & Ahmad, F. (2023). Blended learning sustainability in business schools: Role of quality of online teaching and immersive learning experience. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100776

[38]. Miles, M. P., Grimmer, M., & Franklin, G. M. (2016). How well do AACSB, AMBA and EQUIS manage their brands?. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 34(1), 99-116. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-06-2014-0100

[39]. Opfer, V. D., & Pedder, D. (2011). The lost promise of teacher professional development in England. European Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.534131

[40]. Pekkarinen, V., & Hirsto, L. (2017). University lecturers’ experiences of and reflections on the development of their pedagogical competency. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(6), 735-753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1188148

[41]. Postholm, M. B. (2012). Teachers’ professional development: A theoretical review. Educational Research, 54(4), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2012.734725

[42]. Rao, Z., & Huang, Y. (2023). The impact of International Exchange and cooperation on the scientific research performance of local universities. International Journal of Education and Humanities, 10(2), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.54097/ijeh.v10i2.11586

[43]. Renz, S. M., Carrington, J. M., Badger, T. A. (2018). Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: An intramethod approach to triangulation. Qualitative Health Research, 28(5), 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317753586

[44]. Redgrave, S. D., Grinevich, V., Chao, D. (2022). The relevance and impact of business schools: In search of a holistic view. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(2), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12312

[45]. Runhaar, P., Bouwmans, M., & Vermeulen, M. (2019). Exploring teachers’ career self-management. considering the roles of organizational career management, occupational self-efficacy, and learning goal orientation. Human Resource Development International, 22(4), 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2019.1607675

[46]. Saavedra, A. R., & Opfer, V. D. (2012). Learning 21st-century skills requires 21st-century teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 94(2), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171209400203

[47]. Sancar, R., Atal, D., Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ Professional Development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103305

[48]. Scott, T., Guan, W., Han, H., Zou, X., Chen, Y. (2023). The impact of academic optimism, institutional policy and support, and self-efficacy on university instructors’ continuous professional development in mainland China. SAGE Open, 13(1), 215824402311533. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231153339

[49]. Sison, A. J. G., & Redín, D. M. (2023). If MacIntyre ran a business school… how practical wisdom can be developed in management education. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(1), 274-291. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12471

[50]. Soliman, M., Di Virgilio, F., Figueiredo, R., Sousa, M. J. (2021). The impact of workplace spirituality on lecturers’ attitudes in tourism and Hospitality Higher Education Institutions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100826

[51]. Surahman, E., & Wang, T.H. (2023). In-service STEM Teachers Professional Development Programmes: A systematic literature review 2018–2022. Teaching and Teacher Education, 135, 104326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104326

[52]. Tigelaar, D. E. H., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Meijer, P. C., de Grave, W. S., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2008). Teachers’ Interactions and their Collaborative Reflection Processes during Peer Meetings. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-006-9040-4

[53]. Valentín, E. M. M. (2000). University—industry cooperation: A framework of benefits and obstacles. Industry and Higher Education, 14(3), 165-172. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000000101295011

[54]. Vereijken, M. W., van der Rijst, R. M. (2021). Subject matter pedagogy in university teaching: How lecturers use relations between theory and Practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(4), 880–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1863352

[55]. Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. International Institute for Educational Planning.

[56]. Wayne, A. J., Yoon, K. S., Zhu, P., Cronen, S., Garet, M. S. (2008). Experimenting with teacher professional development: Motives and methods. Educational Researcher, 37(8), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x08327154

[57]. White, M. D., Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends, 55(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0053

[58]. Williams, Z. B. (2021). The impact of business program accreditation on Ranking and enrollment for HBCU Schools. Research Journal of Business and Management, 8(4), 233-242.https://doi.org/10.17261/pressacademia.2021.1465

[59]. Yang, G. L., Fukuyama, H., & Song, Y. Y. (2018). Measuring the inefficiency of Chinese research universities based on a two-stage network DEA model. Journal of Informetrics, 12(1), 10-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.11.002

[60]. Yuan, G., Gao, Y. (2021). Factors impacting an overseas continuing professional development programme: Chinese teachers’ voices. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 43(1), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1918631

[61]. Zhang, H., Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2013). Building global-class universities: Assessing the impact of the 985 Project. Research Policy, 42(3), 765-775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.10.009

Cite this article

Yan,L. (2024). A Model of Lecturer’s Professional Development in Business School of Research Universities in the 21st Century. Advances in Social Behavior Research,6,43-54.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Abzug, R. (2022). Structural drivers and barriers to the strategic integration of sustainability in US B-schools. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(5), 986–1001. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe-10-2021-0433

[2]. Alhassan, A. (2021). Challenges and professional development needs of EMI lecturers in Omani Higher Education. SAGE Open, 11(4), 215824402110615. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061527

[3]. Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher Professional Development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

[4]. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986(23-28).

[5]. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

[6]. Bennett, R. (2006). Business lecturers’ perceptions of the nature of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 12(3), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550610667440

[7]. Boulton, G., & Lucas, C. (2011). What are universities for?. Chinese Science Bulletin, 56, 2506-2517. https://doi: 10.1007/s11434-011-4608-7

[8]. Brouwer, N., Joling, E., & Kaper, W. (2022). Effect of a person-centred, tailor-made, teaching practice-oriented training programme on continuous professional development of STEM lecturers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103848

[9]. Chauhan, S., Goyal, S., Bhardwaj, A. K., Sergi, B. S. (2021). Examining continuance intention in business schools with digital classroom methods during COVID-19: A comparative study of India and Italy. Behavior Information Technology, 41(8), 1596–1619. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2021.1892191

[10]. Chen, R. T. H. (2018). University lecturers’ experiences of teaching in English in an international classroom. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1527764

[11]. Chia, R. (1996). Teaching paradigm shifting in management education: University Business Schools and the entrepreneurial imagination. Journal of Management Studies, 33(4), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1996.tb00162.x

[12]. Choi, J.J., Robb, C. A., Mifli, M., & Zainuddin, Z. (2021). University students’ perception to online class delivery methods during the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus on hospitality education in Korea and Malaysia. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport Tourism Education, 29, 100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100336

[13]. Cooper, S., Parkes, C., & Blewitt, J. (2014). CAN accreditation help a leopard change its spots? Social accountability and stakeholder engagement in business schools. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(2), 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-07-2012-01062

[14]. Davies, J., Thomas, H., Cornuel, E., & Cremer, R. D. (2023). Leading a business school. Taylor & Francis Group.

[15]. Denman, B. (2009), What is a University in the 21st Century?. Higher Education Management and Policy, vol. 17(2),9-28. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v17-art8-en

[16]. Downe‐Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health care for women international, 13(3), 313-321.https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339209516006

[17]. Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the Content Analysis Literature in Organization Studies: Research Themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106289252

[18]. El, A. A. M. M. A. (2023). The role of educational initiatives in EFL teacher professional development: a study of teacher mentors’ perspectives. Heliyon, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13342

[19]. Ferman, T. (2002). Academic professional development practice: What lecturers find valuable. International Journal for Academic Development, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144032000071305

[20]. Gong, Y., MacPhail, A., Guberman, A. (2021). Professional learning and development needs of Chinese University-based Physical Education teacher educators. European Journal of Teacher Education, 46(1), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1892638

[21]. Gribling, M., Duberley, J. (2020). Global competitive pressures and career ecosystems: Contrasting the performance management systems in UK and French Business Schools. Personnel Review, 50(5), 1409–1425. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-05-2019-0250

[22]. ] Gujarathi, M. R., & McQuade, R. J. (2002). Service-learning in business schools: A case study in an intermediate accounting course. Journal of Education for Business, 77(3), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599063

[23]. Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

[24]. Hammond, K., Harmon, H., Webster, R., Rayburn, M. (2004). University Strategic Marketing Activities and Business School Performance. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500410568565

[25]. Huang, B., Jong, M. S. Y., Tu, Y. F., Hwang, G. J., Chai, C. S., & Jiang, M. Y. C. (2022). Trends and exemplary practices of STEM teacher professional development programs in K-12 contexts: A systematic review of empirical studies. Computers & Education, 104577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104577

[26]. King, F. (2013). Evaluating the impact of teacher professional development: An evidence-based framework. Professional Development in Education, 40(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.823099

[27]. Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

[28]. Kociatkiewicz, J., Kostera, M., Zueva, A. (2022). The ghost of capitalism: A guide to seeing, naming and exorcising the spectre haunting the business school. Management Learning, 53(2), 310–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505076211005810

[29]. Krishna, A., & Orhun, A. Y. (2021). Gender (still) matters in Business School. Journal of Marketing Research, 59(1), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243720972368

[30]. Kusters, M., van der Rijst, R., de Vetten, A., Admiraal, W. (2023). University lecturers as change agents: How do they perceive their professional agency? Teaching and Teacher Education, 127, 104097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104097

[31]. Lai, H.M., Hsiao, Y.L., Hsieh, P.J. (2018). The role of motivation, ability, and opportunity in university teachers’ continuance use intention for flipped teaching. Computers & Education, 124, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.013

[32]. Li, J., Xue, E., Li, J., & Xue, E. (2021). The policy analysis of creating world-class universities in China. Creating World-Class Universities in China: Ideas, Policies, and Efforts, 1-33.

[33]. Liang, J., Ell, F., Meissel, K. (2023). Who do they think they are? professional identity of Chinese University-based teacher educators. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2191814

[34]. Liu, H. (2022). Teaching for freedom, caring for ourselves. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(1–2), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2022.2131268

[35]. Loads, D. J. (2009). Putting ourselves in the picture: art workshops in the professional development of university lecturers. International Journal for Academic Development, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440802659452

[36]. Maor, D. (2006). Using reflective diagrams in professional development with university lecturers: A developmental tool in online teaching. The Internet and Higher Education, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.03.005

[37]. Mariam, S., Khawaja, K. F., Qaisar, M. N., & Ahmad, F. (2023). Blended learning sustainability in business schools: Role of quality of online teaching and immersive learning experience. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100776