1. Introduction

Research on children and media began in the 1920s when the film industry was booming in the United States, and the number of moviegoers rapidly increased. Statistics from 1923 show nearly 40 million viewers, including about 17 million children under the age of 14. However, the content of films at that time was similar to today's television content [1]. Educator Edgar Dale analyzed 1,500 films of that era and found that three-quarters of them contained themes of romance, crime, and sex. In 1928, the Motion Picture Research Council, headed by William H. Short, conducted a series of studies to assess the impact of films on children, funded by The Payne Fund. This research, known as the Payne Fund Studies, is regarded by domestic and international scholars as the inception of child and media research. Subsequently, experts began to explore the impact of media on child development. In 1933, British cultural researcher E.R. Leavis and his student Dennis Thompson first introduced the concept of "media literacy".

2. What is "Media Literacy"?

The literal meaning of media literacy is the ability to read and write media. In 1992, the Aspen Institute's Media Literacy Leadership Summit in the United States defined it as "the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media in a variety of forms" [2]. In the same year, the American Center for Media Literacy also defined media literacy as follows: "The ability of individuals to select, question, understand, evaluate, create, and produce information when faced with various forms of information from different media, as well as the ability to engage in critical thinking."

In 2001, W. James Potter wrote in "Media Literacy" that media literacy is our insight into media information, which is built on our knowledge structure. We need tools and materials to build this knowledge structure, with skills being our tools and media and the real world being the materials. Actively using these abilities means we can correctly understand media information and interact with it. In 2003, researchers Xie Guanwen and Yu Jian pointed out in "A Brief Discussion on Media Literacy Education" that media literacy refers to the ability of individuals to correctly judge and evaluate the meaning and function of media information, as well as the ability to effectively create and disseminate information. With the popularization of computers and the internet, concepts such as computer literacy, information literacy, and internet literacy have been proposed. In the information age, media literacy not only includes the ability to judge information but also the ability to effectively create and disseminate information [3]. In 2005, researcher Zhang Yanqiu mentioned in "An Analysis of Foreign Media Education Development" that media literacy encompasses three levels of significance. The first level is the ability of individuals to recognize the importance of balancing and managing their media "diet", i.e., how to reasonably choose and allocate time for media use. The second level is to master specific, critical media use abilities, such as analyzing and questioning media structures and information. The third level is the ability to delve into the underlying framework of media and further explore the purposes of media information production [4]. In 2006, researcher Xie Jinwen wrote in "Introduction to Journalism and Communication" that media literacy is the literacy of individuals in understanding, using, and participating in mass media. It not only includes personal media literacy but also the media literacy of social environments, social organizations, media institutions, and power institutions [5]. In 2006, researcher Zhang Kai pointed out in "Introduction to Media Literacy" that media literacy refers to the ability of individuals to select, understand, question, evaluate, think critically, adapt, create, and produce media messages when faced with various messages from the media [6]. In 2009, Julia Wood wrote in "Media in My Life" that media literacy is understanding the impact of mass media and approaching, analyzing, evaluating, and responding to mass media from multiple perspectives in a critical manner. In 2015, scholar Liu Yong wrote in "Introduction to Media Literacy" that media literacy refers to people's ability to understand the characteristics and functions of different media, interpret and critique media dissemination of information, and participate in media, use media, and its information for personal survival, development, and social progress [7]. In summary, we believe that media literacy is the ability, in an era of concurrent development of various media and information explosion, to select the information one needs from a plethora of information, discern the authenticity of information, and transform the collected information into one's own knowledge for flexible application.

3. Definition of Media Literacy Education

Media literacy education originated in the Western developed countries in the 1930s, stemming from the educational concepts of British scholars and Danish workers. Since the second half of the 20th century, media education has gradually emerged as a new teaching subject in Europe, North America, Oceania, Latin America, and some parts of Asia. As of today, countries such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Norway, Finland, and Sweden have incorporated media literacy education into the formal education systems of primary and secondary schools in whole or in part [11]. There are diverse opinions among scholars regarding the definition of media literacy education, but a relatively unified perspective is that media literacy education is a form of education aimed at cultivating and improving students' media literacy, guiding them to correctly understand and constructively utilize mass media resources. Through this education, students can more keenly discern and analyze media information, thus better adapting to the challenges of the information age [9].

4. Current State of Media Literacy Education

As of December 2022, China has 1.067 billion internet users, with an internet penetration rate of 75.6%, of which minors make up 18.7%. The penetration rate among minors far exceeds the overall level, marking them as witnesses and builders in the digital era [10]. Against this backdrop, we conducted a survey study involving 422 children in Hohhot, Xilin Gol, Chifeng, and Tongliao in Inner Mongolia. The results show that mobile phones are the primary media used by children daily, accounting for 70%. Additionally, they use tablets, computers, TVs, and other media in their daily lives (see Table 1).

Table 1. Other Media Used in Daily Lives

Options |

Subtotal |

Proportion |

A.Mobile |

297 |

|

B.Tablet |

59 |

|

C.computer |

42 |

|

D.television |

24 |

|

Validly fill in the number of people |

422 |

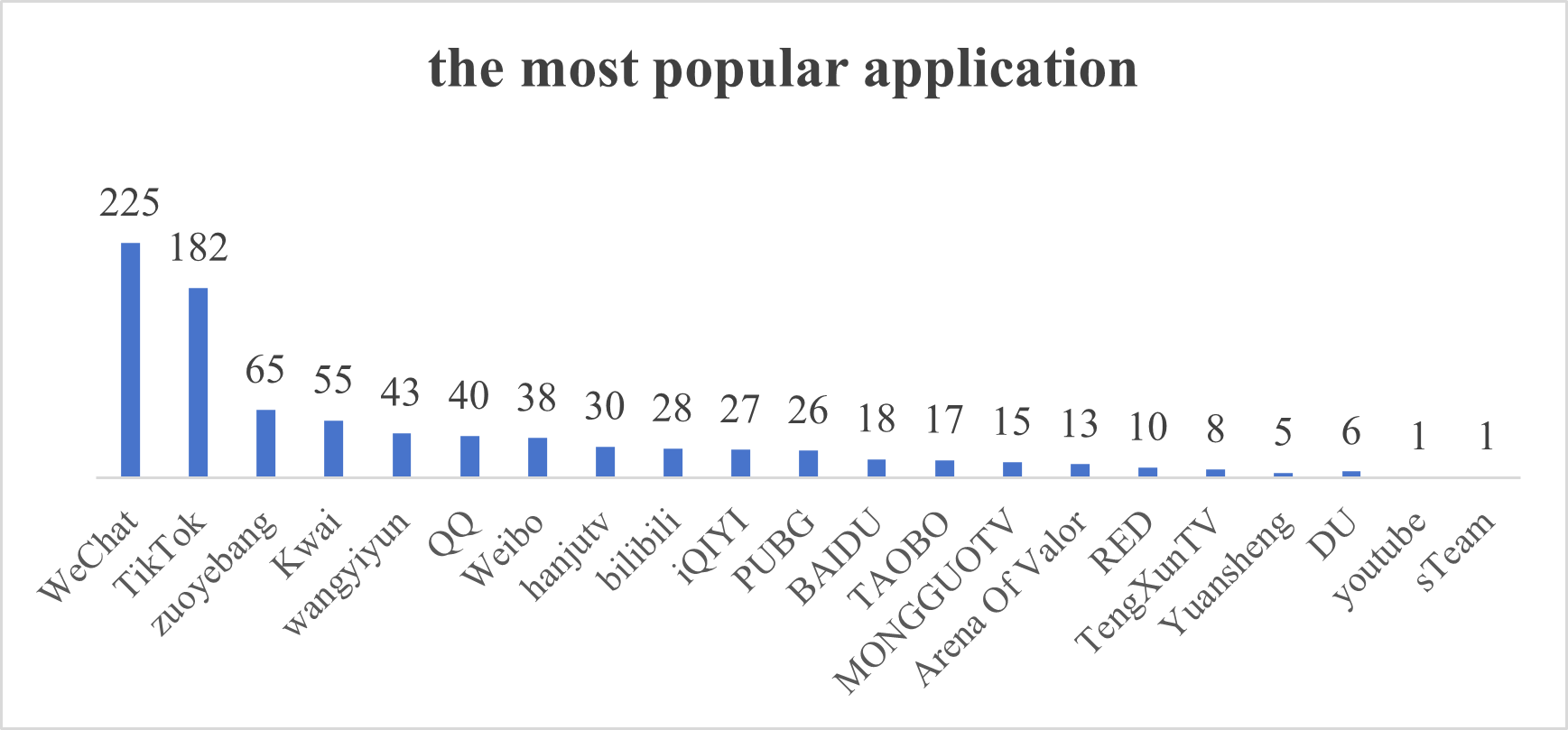

The study indicates that the main purposes for minors to access various media include leisure, social communication, news acquisition, and satisfying learning needs (see Table 2). Their daily media exposure is primarily between 1-2 hours (see Table 3). In daily life, apps like WeChat, TikTok, and Homework Help are used most frequently (see Figure 1). It is evident that daily internet use has become a norm for minors, with chatting, entertainment, and learning online becoming significant aspects of their "digital lives." In the contemporary era, the functions of the internet extend beyond entertainment to include learning and social interaction. The widespread use and functional expansion of internet scenarios have demystified the internet for minors, leading to a more specific and comprehensive understanding of its applications.

Table 2

Options |

General assessment |

№1 |

№2 |

№3 |

№4 |

№5 |

Average sum |

For leisure and entertainment |

3.24 |

124(30.69%) |

85(21.04%) |

76(18.81%) |

60(14.85%) |

59(14.6%) |

404 |

For social interaction, public relations |

3.17 |

133(33.5%) |

44(11.08%) |

100(25.19%) |

78(19.65%) |

42(10.58%) |

397 |

Learning requirements |

2.75 |

61(16.09%) |

100(26. 39%) |

76(20.05%) |

85(22.43%) |

57(15.04%) |

379 |

Obtain knowledge and information |

2.53 |

67(17.27%) |

60(15.46%) |

75(19.33%) |

81(20.88%) |

105(27.06%) |

388 |

To spend time |

2.44 |

37(9.89%) |

105(28.07%) |

60(16.04%) |

73(19.52%) |

99(26.47%) |

374 |

Table 3

Options |

Subtotal |

Proportion |

A.Less than 1 hour |

99 |

|

B.1-3 hours |

182 |

|

C.3-5 hours |

89 |

|

D.More than 5 hours |

52 |

|

total |

422 |

Figure 1. The Most Popular Applications

During our research, we identified the following issues:

1、 Minors exhibit poor self-regulation in media use, such as using mobile phones in class. Additionally, 40% of minors occasionally allow media to disrupt their study plans, and 17% often find their learning delayed due to media use.

2、 They struggle to clearly distinguish between the online world and the real world. Regarding the view that "media reports are a mirror of reality, reflecting it truthfully," 44% of minors are unclear, 39% agree, and when it comes to actively considering the truth of media information, 44% say they only sometimes do.

3、 There is a lack of media literacy education. Among surveyed minors, 54.74% reported that their schools do not have a dedicated media literacy curriculum. Only 25.59% mentioned that media literacy is occasionally addressed through class meetings or lectures, and the same percentage stated that their schools have never focused on media literacy education.

Moreover, according to the "China Minors Internet Application Report (2023)" surveying minors' internet literacy courses in 2022, 34.8% have never heard of or attended an internet literacy course, 33.8% have heard of but not attended such courses, 16.9% are unsure what an internet literacy course entails, and only 14.4% have attended or are attending such a course. This reveals the current state of digital literacy education among Chinese minors. The report also notes the prevalence of shallow internet reading habits, "fast food culture," and "information disorientation" online among minors, highlighting an urgent need to advance digital literacy education in China.

5. Objectives of Media Literacy Education

German education worker Nicole Bergmann pointed out: "Everything that appears in children's lives should be given attention in education. Therefore, we should regard television, newspapers, computers, and other media as part of children's daily lives and incorporate them into educational work. Children should develop the ability to access various things in all educational fields. Computers and their functions are also among such things, and we should focus on making various media available to children as everyday tools." In countries like Germany, the United Kingdom, and Denmark, media literacy education started early and has accumulated rich experience. We can learn from their educational objectives and methods and carry out localized reforms accordingly.

5.1. Provide Children with Experience and Knowledge of Media Use

This is one of the fundamental objectives of media literacy education. According to the psychological and physiological development of children, those aged 1-2 view media as interesting and playable items and show interest and preference for the information displayed by media, such as certain nursery rhymes or early education books. Children aged 3-4 exhibit clear preferences for certain types of media, such as specific cartoons or songs, and they actively use familiar media. By the age of 5-6, children can operate a certain type of media independently or with peers and adults. Based on this, we can attempt to incorporate the objective of providing children with experience and knowledge of media use into pre-school education, allowing them to discover and try using media products or technologies in daily life.

5.2. Equip Children with the Ability to Use Media to Meet Their Own Needs, Solve Problems, and Engage in Social Communication

Data from the "Youth Blue Book" shows that in 2022, minors believed that the benefits of social media platforms primarily lie in "easier access to knowledge," "more convenient social interaction," "easier learning, with many courses/assignments available online," and "more new games and entertainment methods." Comparing data from the "China Minors Internet Application Status Survey" in 2020 and 2022, minors' rankings of the benefits of social media platforms have remained consistent in recent years. Social media platforms have become important channels for minors to acquire knowledge, with their informational significance surpassing their social significance in minors' perceptions. It is evident that minors are gradually using media as sources of information and learning tools. At the same time, the survey from the "Youth Blue Book" in 2022 showed that the majority of minors use social media platforms to maintain social relationships in real life (82.3%); some minors expand their online social circle while consolidating offline social relationships (12.2%); only a few minors focus on expanding online social connections through social media platforms (5.5%). Minors growing up in the information age are attempting to break through the limitations of offline social interaction and expand their social circles and meet social needs through online channels. However, accompanying problems have gradually emerged, such as their superficial attention to social events, inability to express their thoughts through media, entertainment needs squeezing out other needs, and causing harm to their physical and mental development. Therefore, in the current context of the compatible development of various media, equipping children with the ability to use media to meet their own needs, solve problems, and engage in social communication is not only our educational objective but also a requirement of children themselves.

5.3. Enabling Children to Reflect on and Summarize Their Relationships with Media

Some scholars believe that emotionally, media experiences have a stronger impact on children than on adults. Children actively connect what they see and hear with themes relevant to themselves. Therefore, media provide children with excellent opportunities to deal with contradictions and fears. Children often see heroes and fairy tale characters from television as symbols of identity and projection to cope with conflicts and fulfill desires. In these role-playing games, they can experience a sense of power and strength, and symbolically fulfill wishes and resolve conflicts in their fantasies. Children also actively adapt characters and stories from media to fit their emotional states and environments. Since children often incorporate media information into their imaginative and fantasy play, it is difficult to predict whether the media's emotional impact on them is positive or negative. The goal of such educational activities is to develop children's ability to manage both positive and negative emotions triggered by media, and to reflect on their own ways of using media.

5.4. Enabling Children to Understand and Independently Think about the Ways and Functions of Media Production

For children, distinguishing between the real world and the "media world" is most challenging when it comes to television images. Studies show that most 3-year-olds believe that the characters on TV live inside the television set, but no child thinks that a radio announcer's home is inside the radio. A significant number of children also believe that people on TV can see and hear the audience, and they often do not abandon the idea that "things on TV also exist in real life" until they reach school age. Therefore, the goal of these educational activities is to enable children to have a substantive understanding of the information carried by media and its functions, to understand the creative intent behind media messages, and to recognize that media content is created by people.

6. Educational Methods of Media Literacy Education

6.1. Interactive Engagement with Media

Utilizing media to interact with students can create a dynamic, innovative, and collaborative learning environment. Children gradually deepen their understanding of the world by actively engaging with their surroundings, expressing their viewpoints, and interacting with others, including peers and adults. This social learning process, in which children and teachers actively participate together, holds significant meaning and value for media literacy education. In this process, media serves as an essential tool, providing rich content for teaching. Children can communicate using media, engage in discussions with adults, share their experiences and thoughts, and thereby reinforce their learning.

6.2. Learning About and Through Games

For children, games are the most fundamental way of learning. During gameplay, children explore various phenomena around them, summarize experiences, and expand their knowledge. Games also enable children to interact with others, build social relationships, express emotions, and enhance self-regulation skills. Children can learn about and through media through activities like role-playing in games, which serves as an excellent learning method.

6.3. Enhancing Children's Mastery of Learning Methods through Media

In media literacy education, children can enhance their ability to grasp learning methods by mastering relevant media knowledge and improving their media usage skills. Children can utilize media for learning by searching for and collecting information, gaining a better understanding of information. Additionally, they can use media to document their learning processes, publish their learning achievements, and share them with others. By correctly utilizing media and mastering learning methods, children can avoid being overwhelmed by fragmented information.

Conclusion

As we enter the era of new media, children are being exposed to media at increasingly younger ages. From birth, they find themselves enveloped in a reality intertwined with mediated spaces, facing a digitized existence and relationships between humans and machines in an era of intelligence. In such an environment, media literacy education is crucial. It equips children to distinguish between real society and media portrayals, enabling them to skillfully handle the various challenges brought by the new media age. However, surveys indicate a significant gap in media literacy education within preschool and primary education in China.

The absence of media literacy education could lead to children's inability to differentiate between the virtual world and real society, their failure to find the information they need among a plethora of messages, and an excessive immersion in media that could hinder their development. It might also subtly influence their perspectives on life and the world. Neil Postman once said, "The peculiarities of media mean that while it guides how we perceive and understand things, its involvement often goes unnoticed." This implies that media can shape one's worldview, values, and problem-solving approaches in ways often not recognized. Therefore, it is imperative to teach children to remain vigilant towards media information, to question, and to discern the truth from the false information they encounter.

References

[1]. Lowery, L. A., & DeFleur, M. L. (2009). Milestones in mass communication research (3rd ed.) (H. L. Liu et al., Trans.). China Renmin University Press.

[2]. Zhang, Y. Q. (2012). Understanding media literacy: Origins, paradigms, and paths. People's Publishing House.

[3]. Zhang, G. W., & Yu, J. (2003). Discussion on media literacy education. China Vocational and Technical Education, 200313.

[4]. Zhang, Y. Q. (2005). Exploration of the development of foreign media education. International Journalism, 200502.

[5]. Xie, J. W. (2006). General theory of journalism and communication. Fudan University Press.

[6]. Zhang, K. (2006). Introduction to media literacy. Communication University of China Press.

[7]. Liu, Y. (2016). Introduction to media literacy. China Renmin University Press.

[8]. Kellner, D. (2013). Media culture: Cultural studies, identity and politics between the modern and the postmodern (N. Ding, Trans.). Commercial Press.

[9]. Fidakos, V. E. (2022). Media literacy education for preschool children in Germany (Y. N. Li, Trans.). Northeast Normal University Press.

[10]. Fang, Y., Li, W. M., Shen, J., et al. (2023). Chinese minors' internet usage report (2023). Social Sciences Academic Press.

[11]. Li, M., & Zhang, X. M. (2006). Drawing on the beneficial experiences of Western media education to construct media education with Chinese characteristics. Journal of Shanghai Normal University (Education Edition), 20061225.

Cite this article

Bayar,C.;Su,H.;Alatengsuhe,A. (2024). Current Status of Media Literacy Education for Children. Advances in Social Behavior Research,8,26-31.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lowery, L. A., & DeFleur, M. L. (2009). Milestones in mass communication research (3rd ed.) (H. L. Liu et al., Trans.). China Renmin University Press.

[2]. Zhang, Y. Q. (2012). Understanding media literacy: Origins, paradigms, and paths. People's Publishing House.

[3]. Zhang, G. W., & Yu, J. (2003). Discussion on media literacy education. China Vocational and Technical Education, 200313.

[4]. Zhang, Y. Q. (2005). Exploration of the development of foreign media education. International Journalism, 200502.

[5]. Xie, J. W. (2006). General theory of journalism and communication. Fudan University Press.

[6]. Zhang, K. (2006). Introduction to media literacy. Communication University of China Press.

[7]. Liu, Y. (2016). Introduction to media literacy. China Renmin University Press.

[8]. Kellner, D. (2013). Media culture: Cultural studies, identity and politics between the modern and the postmodern (N. Ding, Trans.). Commercial Press.

[9]. Fidakos, V. E. (2022). Media literacy education for preschool children in Germany (Y. N. Li, Trans.). Northeast Normal University Press.

[10]. Fang, Y., Li, W. M., Shen, J., et al. (2023). Chinese minors' internet usage report (2023). Social Sciences Academic Press.

[11]. Li, M., & Zhang, X. M. (2006). Drawing on the beneficial experiences of Western media education to construct media education with Chinese characteristics. Journal of Shanghai Normal University (Education Edition), 20061225.

70.38%

70.38%

13.98%

13.98%

9.95%

9.95%

5.69%

5.69%

23.46%

23.46%

43.13%

43.13%

21.09%

21.09%

12.32%

12.32%