1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development, extensive reach, and profound impact of the digital economy have been unprecedented. It is becoming a key force in reshaping global resource allocation, restructuring the global economic structure, and altering the global competitive landscape. General Secretary Xi Jinping attaches great importance to expanding and strengthening the digital economy, emphasizing the need to fully leverage the role of informatization in guiding economic and social development. The 14th Five-Year Plan and the Outline of the 2035 Vision for the future specifically outline the goal of “accelerating digital development and building a digital China” as a separate section, while dedicating a separate chapter to “creating new advantages in the digital economy,” requiring “the full utilization of the advantages of massive data and rich application scenarios to promote the deep integration of digital technologies with the real economy, empower the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, and foster new industries, new business forms, and new models to strengthen the new engines of economic growth.” This provides a clear direction for the development of China’s digital economy.

The latest judicial interpretation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law came into effect on March 20, 2022. It clarifies the definition and criteria of unfair competition behavior, aiming to safeguard the healthy development of the market economy, encourage fair competition, and protect rights and interests. However, there are still shortcomings in the integration of judicial interpretations with judicial practices. This paper intends to promote the use of judicial interpretations in practice through empirical research, providing legal support for case adjudication. Taking the 2017 “Taobao vs. Meijing case” as an example, the court acknowledged that data controllers, such as enterprises, hold property rights over the data they collect and process. However, it also cautiously treated the strength of these property rights, limiting their effectiveness to a certain scope, recognizing them as limited competitive property rights. In judicial practice, when data is not clearly regulated or restricted, legal application becomes difficult. The specific provisions for the internet become “zombie clauses,” and improper data crawling behavior occurs frequently, as seen in cases such as the unfair competition dispute between Beijing Taoyou Tianxia Technology Co., Ltd. and Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd., and the unfair competition dispute between Shenzhen Gumi Technology Co., Ltd. and Wuhan Yuanguang Technology Co., Ltd. Although the general provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law can still be applied to adjudicate these cases, they fail to effectively protect the interests of businesses and regulate the efficient and orderly development of the digital economy under a market economy. Therefore, the author defines data as publicly available data sets that businesses legally collect from users and transform through labor, thus giving them commercial value. This paper will also use empirical research to better apply the Anti-Unfair Competition Law to regulate unfair practices during the data crawling process.

2. Empirical Investigation of Judicial Rulings on Data Crawling Cases

2.1. Selection of Judicial Samples and Basic Information on Data Crawling Cases

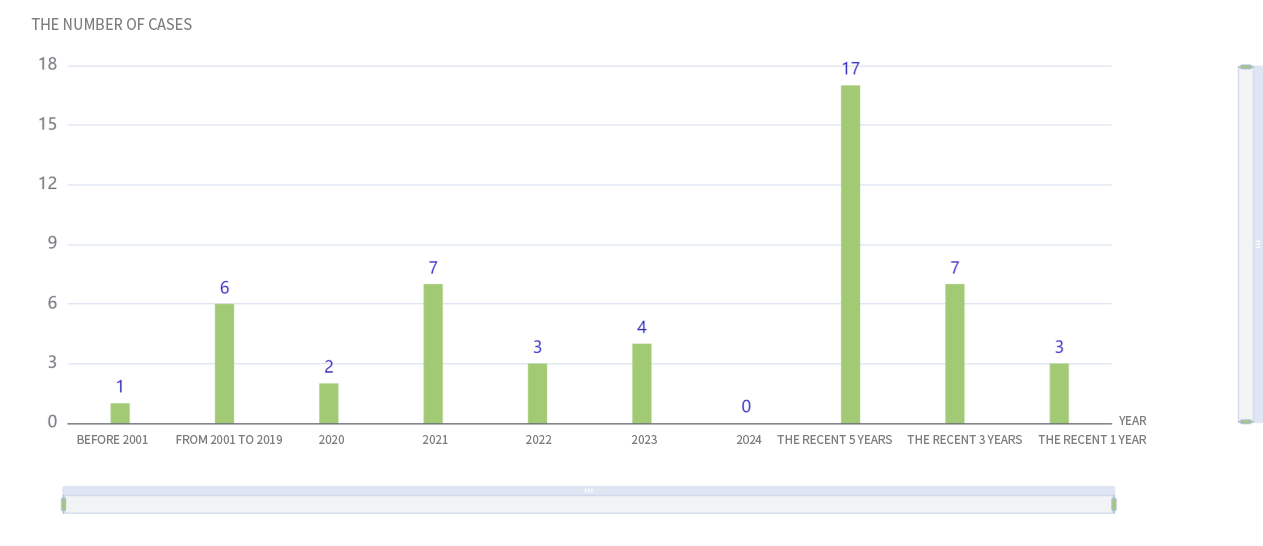

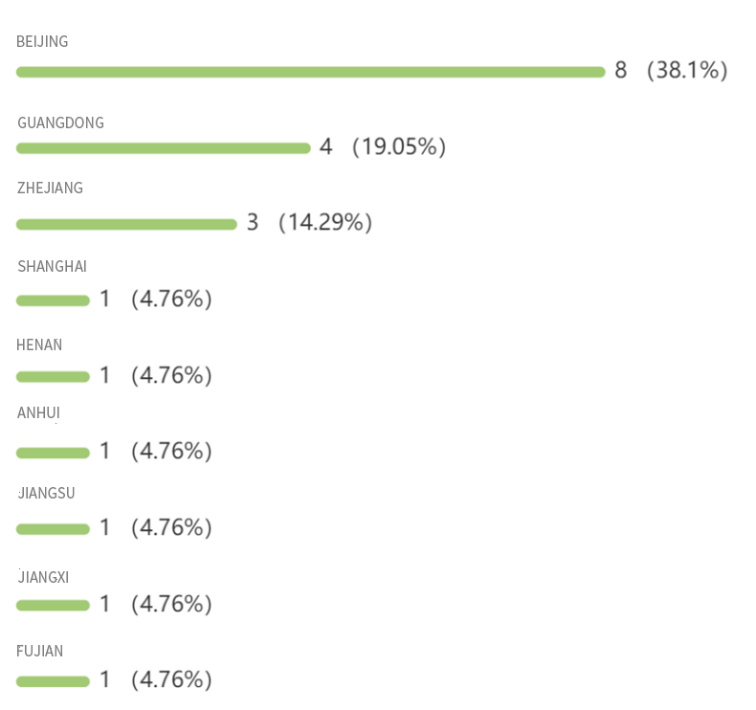

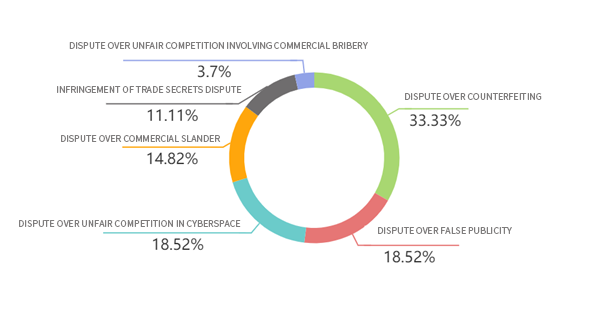

The author conducted a cross-search using the keywords “data crawling” and “Anti-Unfair Competition Law” on platforms such as the China Judgments Online and FaXin, selecting 27 representative judicial rulings in total [1]. As shown in Figure 1, 77% of these cases occurred after 2019. The judgments were predominantly made in economically developed regions such as Beijing, Guangdong, and Zhejiang (as shown in Figure 2). The main causes of action in these cases were issues of imitation, unfair competition on the internet, and false advertising (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 1. Data Crawling Case Adjudication Years

Figure 2. Data Crawling Case Adjudication Locations

Figure 3. Causes of Action in Data Crawling Cases under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law

2.2. Characteristics of Judicial Rulings in Data Crawling Cases

For data usage, the open sharing of data resources is an essential pathway for the development of the digital economy, but data protection is also an unavoidable practical need [2]. Regarding the legitimacy of crawling activities, 86.96% of defendants lost their cases, with their crawling activities being deemed in violation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Judicial determinations of crawling activities in these cases show two main characteristics.

In judicial practice, adopting the Anti-Unfair Competition Law as the legal basis to regulate data crawling and its subsequent application has gained widespread legal consensus. A detailed analysis of 27 judicial cases reveals that when courts examine the “data crawling + utilization” strategy employed by defendants, their core focus is to assess whether this strategy is unfair under the framework of competition law, using this as the benchmark to define the nature of the defendant’s actions. At present, neither the analysis of legal provisions and legal doctrines nor the analysis based on legitimacy and consequentialism can fully clarify the ownership of data. The reason for this is that platform data has multiple attributes, and its characteristics are highly dependent on the context [3]. The core logic behind using anti-regulation is that it directly evaluates the legitimacy of the behavior itself, without presuming that businesses have specific rights to the data. This approach cleverly bypasses the complexity and controversy often associated with confirming data ownership in such cases. Therefore, the focus of disputes in litigation is not on the final ownership of data rights but on which party holds more reasonable, rather than absolute, rights after a comprehensive consideration.

When evaluating the scope of unfair competition, the judicial community has broadly accepted the moderate expansion of the criteria for defining competitive relationships. In the cases reviewed, no court denied the existence of a competitive relationship between the parties. Some judicial bodies hold the view that a competitive relationship is not a necessary prerequisite for infringement, while other courts have taken a more open stance, extending the concept of a competitive relationship to include interactions between non-direct competitors. This trend is largely due to the fact that data crawling activities mainly concentrate in information technology-intensive fields such as the internet, where platform economies often exhibit clear characteristics of two-sided markets. This means that even in the absence of traditional direct competition, operators may still find themselves in a competitive situation due to conflicting interests. For example, in the “WeChat and JuKe Dispute” case, the defendant argued that its social commerce application and the plaintiff’s instant messaging service belonged to different business fields. However, according to the Judicial Interpretation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law issued in 2022, any market entity that may have a risk of competing for transaction opportunities or competitive advantages in the course of business operations may be legally recognized as “other operators” under Article 2 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. This legal interpretation provides solid support for the practice of broadly interpreting competitive relationships in judicial practice, thus further consolidating the consensus in the judicial field.

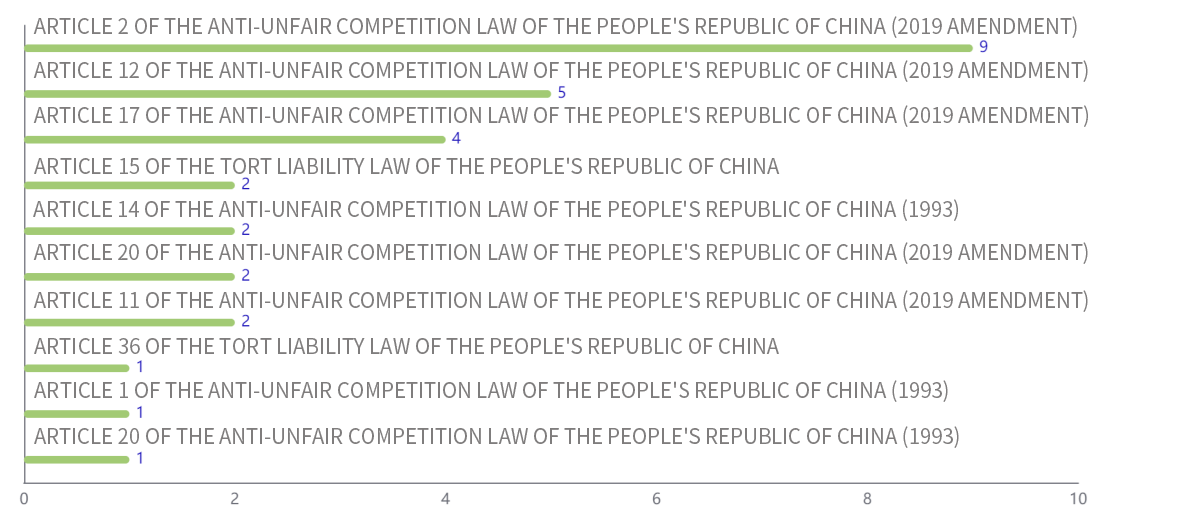

2.3. Application of General Provisions and Internet-Specific Provisions in Legal Articles

In handling data crawling cases with similar behaviors, courts generally apply the 12th article, the “Internet-Specific Clause,” and the second article, the “General Provisions,” of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. It is worth noting that, compared to Article 12, the second article, the “General Provisions,” is more frequently applied in practice.

Figure 4. Legal Provisions Cited in Data Crawling Cases

In cases involving crawling behaviors that damage server performance, most courts base their judgments on the provisions of Article 12, Paragraph 4 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, categorizing such behaviors as “actions that interfere with or disrupt the normal operation of network products or services provided by other operators.” In general, if a defendant uses technical measures to bypass the plaintiff’s technical protection measures and crawl non-public data, this is considered “destructive” [4]. However, since the capacity of the plaintiff’s server for load-bearing and optimization varies in individual cases, determining the extent to which crawling public data, especially user-uploaded data, is “destructive” differs significantly from case to case. For instance, in a case where WeChat was the plaintiff, some courts did not consider the quantity of information crawled as a factor but instead directly deemed that automated, large-scale operations would increase the data load and data flow on the plaintiff’s system, leading to a heavier operational burden, reduced stability, and diminished efficiency, ultimately hindering normal operations [2]. Other courts, however, argued that WeChat, as an open internet platform, is inherently capable of handling massive user access, and machine-based bulk access achieved through technical means would not directly disrupt or hinder the platform’s functionality. Some courts, taking into account the defendant’s average of over 745,000 crawling requests per day, considered that this level and frequency of requests would impose a much greater burden on the WeChat server than normal user access [5].

The greatest uncertainty and controversy in the application of legal provisions lies in the determination of the behavior after data crawling. The vast majority of courts recognize the conflict between the application of the “specific provisions” and the “general provisions” and can only apply one of them [6]. The term “normal operation” in Article 12 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law is ambiguous, and a reasonable judgment of this element inevitably leads back to the interpretation of the general provisions, causing Article 12 to become “zombie legislation” [7]. Moreover, the concept of “abuse” under Article 2 has become a common evaluative standard [8]. Whether this will lead to an escape to general principles in the judgment of crawling behavior remains a shared concern among scholars, as legitimacy interpretations depend on judicial reasoning, which requires higher levels of explanation in individual cases.

2.4. Value Orientation in the Determination of Data Crawling Behavior — Adherence to the Balance of Multiple Interests

In the internet industry, leading companies build competitive advantages by leveraging vast datasets, using robots.txt protocols, contractual clauses, and technical barriers to prevent unauthorized data scraping, with the aim of monopolizing and effectively utilizing these data resources. However, web crawling technology plays an indispensable role in maintaining the diversity of the internet ecosystem [9]. On an international scale, businesses frequently resort to legal measures, seeking judicial clarification on the boundaries of the legality of data scraping activities. For publicly accessible data, establishing the reasonable limits of the legitimacy of web crawling activities is particularly important. For example, in the case of Weimeng vs. Yifang, Weimeng operated the “Weibo” platform, while Yifang scraped Weibo data without permission through the “Eagle Strike” system, processed the data, and sold it as a data product. Weimeng considered this to be unfair competition and demanded that Yifang cease scraping and compensate for damages. The first-instance court ruled that Weimeng had legal rights over the Weibo data, and Yifang’s unauthorized collection and commercial use of non-public data constituted unfair competition. The court’s rationale stated that Yifang failed to provide adequate evidence of the legality of its access to public data, and its actions infringed upon user privacy rights and the legal rights of the platform. The subsequent appeal and retrial upheld the first-instance judgment. Later, Yifang’s software claimed in a public account that Sina Weibo’s refusal to grant data access constituted a monopoly, requesting the court to allow it to use the data and seek compensation. Some scholars have pointed out that large platforms win over 80% of unfair competition lawsuits against smaller platforms, whereas there are no cases where smaller platforms win monopoly lawsuits against larger platforms [10], reflecting the disadvantages of non-data controllers in the data field.

From the perspectives of both the plaintiff and defendant, both parties believe their actions promote the maximization of information flow and are beneficial to the public good. In the assessment, priority should be given to considering the public interest, followed by group interests, and finally individual interests, in order to more accurately judge whether the actions violate commercial ethical standards [11]. In this value assessment process, attention should be extended to consumers and other competitors in the market, analyzing whether the alleged behavior contributes to improving consumer welfare, incentivizing industrial innovation, driving technological progress, and adjusting the existing imbalanced interests, thus avoiding the formation of a substantive monopoly situation.

3. The Controversies and Solutions of Regulating Data Crawling Behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law

3.1. Disputes over the Application of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law to Data Crawling Cases

In the context of data crawling cases, there are two main approaches in the academic community: competition law protection and empowerment protection [12]. Scholars who support empowerment protection argue that competition law protection can only assess the behavior on a case-by-case basis, without addressing the fundamental issue of the ownership of data. Therefore, they believe that competition law is merely a temporary solution, and empowerment protection is the ultimate approach for such cases. Some scholars suggest that in past judicial practices, courts often regulated data crawling behavior based on Article 2 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, determining the legitimacy of the behavior by examining whether it violated business ethics. However, this model has certain problems. Business ethics standards are inherently vague, and an over-reliance on business ethics could potentially restrict the development of behaviors with higher economic efficiency [13]. After conducting empirical analysis, the author believes that the regulation under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law is more reasonable and feasible.

3.2. The Rationality of Regulating Data Crawling Behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law

Firstly, data possesses core and fundamental attributes such as non-competitiveness, non-exclusivity, and intrinsic value. The non-competitiveness of data means that it can be used by multiple parties simultaneously without interfering with or diminishing its utility, which is significantly different from traditional goods or services. This characteristic ensures that data resources cannot be monopolized by a single entity in the market, thus promoting the free flow and sharing of information, providing fertile ground for market innovation and development. The non-exclusivity of data further reinforces its nature as a public resource. Unlike physical assets, the existence and use of data do not exclude other parties from accessing or utilizing the same data, helping to break down information silos and fostering cross-industry integration and innovative applications of data. This openness not only enhances the utilization efficiency of data resources but also promotes collaboration and integration across different industries, accelerating the arrival of the digital economy era. The intrinsic value of data is one of its most unique and important attributes. The value of data is not external to the data itself but stems from the richness, accuracy, and completeness of its content, as well as its diverse applications in different scenarios. This means that the value of data depends not only on its quantity but also on how it is mined, analyzed, and utilized. This intrinsic value drives enterprises to continuously explore new data processing technologies and application models to maximize the economic and social benefits of data, while also presenting challenges and opportunities for the regulation under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. The legal framework needs to protect the legitimate rights and interests of data innovators while maintaining fair market competition.

These attributes ensure that data, as a special resource, is not monopolized or excluded by any single entity in the market, and its value derives from the richness of its content and the diversity of its applications. The regulation under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law not only strictly adheres to the core and fundamental attributes of data, such as non-competitiveness, non-exclusivity, and intrinsic value, but also deeply aligns with the fundamental spirit and core concept of “interconnection and information sharing” advocated in the big data era. It emphasizes the free and open flow of data, promotes data exchange and integration among different entities, and provides solid legal support for building a more open, inclusive, and collaborative data ecosystem, which contributes to the high-quality development of the digital economy and the maximization of social benefits.

Secondly, the regulatory principles of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law not only deeply align with the objective laws of internet market economy development but also demonstrate a thorough understanding and high respect for the inherent logic of market operations. Particularly, it emphasizes the protection and promotion of free competition in the data market. This legal framework is based on profound insights into market dynamics and the characteristics of the data economy, aiming to create a vibrant yet fair and orderly market environment. Specifically, the Anti-Unfair Competition Law clearly defines the boundaries of unfair competition behavior through a series of detailed and precise provisions, providing clear guidelines for market participants. This approach effectively curbs unfair competition phenomena such as false advertising, commercial defamation, and free-riding, protecting the rights of legitimate operators, while also preserving ample competitive and innovative space for enterprises in the vast internet space. In such a fair, just, and transparent market environment, enterprises are free to compete based on their own strength and innovative capabilities, constantly exploring new business models and technological frontiers, driving the continuous progress and development of the entire industry. More profoundly, the implementation of this regulatory strategy not only helps maintain market health and stability but also significantly improves the competitive efficiency of the data market, promoting the optimal allocation and efficient utilization of data resources. Under the protection of the law, data, as a key production factor in the new era, is fully energized in terms of its flow, sharing, and innovation, injecting continuous powerful momentum into the sustained prosperity of the internet economy. This has not only accelerated the development of the digital economy but also promoted the deep integration of traditional and emerging industries, laying a solid foundation for building a smart society and achieving high-quality economic development.

Currently, applying the general provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law to data crawling cases has become a common practice in judicial proceedings [14]. It is evident that the Anti-Unfair Competition Law is sufficient to resolve such disputes. In light of the ongoing controversy surrounding data empowerment, setting aside the disputes and optimizing the regulatory approach of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law to fill judicial gaps is a more feasible path. The author will re-optimize macro-regulatory concepts and micro-behavioral determinations to improve the application of general provisions in data crawling cases.

4. The Challenges and Responses in Determining Data Scraping Behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law

4.1. Determination of Competitive Relationship

Article 2, paragraph 3 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and Article 2 of the Supreme People’s Court’s Interpretation on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of the People’s Republic of China reaffirm the judicial stance on determining a broad competitive relationship. This stance no longer regards the existence of the same industry, same field, same business operation, or same business model as the premise for determining competition, but instead, it is based on the judgment of damage arising from the competing interests of parties involved.

In fact, under the rapid development of the internet economy, the element of competitive relationships has gradually lost its original normative significance. Traditional definitions of competitive relationships are often limited to direct competition between industries or similar businesses. However, in the internet economy, the competition model has undergone a fundamental shift, with cross-industry competition becoming mainstream. The core of this competition lies in the intense pursuit of traffic. This competition model displays an open, integrative characteristic that covers the entire internet market, no longer confined to specific industries or fields, but spanning multiple dimensions and boundaries. In such a competitive environment, the competitive relationship has become dynamic and omnipresent. The competition between businesses is no longer limited to traditional market share battles but is increasingly reflected in aspects such as innovation capacity, user experience optimization, and the integration and utilization of data resources. Therefore, the occurrence of competitive relationships has become difficult to predict and define; it may arise anytime and anywhere between different businesses, evolving continuously with changes in the market environment and consumer demand. At the same time, the behaviors connecting competitive relationships have become varied and numerous. Businesses may engage in competition through various means such as technological innovation, product iteration, and marketing strategy adjustments, often crossing traditional industry boundaries, making the line between competitive relationships and competitive behaviors increasingly blurred. Thus, under the internet economy, there is no necessarily direct or fixed relationship between competitive relationships and competitive behaviors, but rather a more complex and variable interactive model.

In conclusion, the competitive relationship element under the internet economy has lost its original normative meaning, and the relationship between competitive behaviors and competitive relationships has become more complex and difficult to define. This requires a more open, flexible, and innovative mindset in understanding and responding to market competition, to adapt to the ever-changing market environment. Additionally, as the Anti-Unfair Competition Law begins to achieve “triple protection” for operators, consumers, and market order, the focus of its application is gradually shifting towards determining the legitimacy of behaviors. Therefore, it is necessary to interpret the significance of competitive relationships in the Anti-Unfair Competition Law in a manner that aligns with current realities and follows the trend of the times, acknowledging that the relative dissolution of “competitive relationships” is now an indisputable fact.

4.2. Determination of Competitive Damage

Firstly, the competitive damage here must refer to damage to the competitive interests of the operator being scraped. This is a threshold requirement for the general provisions, meaning there can be no unfairness without damage, and only after the presence of damage can its legitimacy be judged. For behaviors that cause no actual harm or harm that is minimal, judicial intervention should not be made, which is in line with the thinking and approach of competition law [15].

Secondly, the forms of competitive damage in reality are extremely diverse and rich, involving not only economic costs and technological investments but also the business reputation and market competitiveness of enterprises. Specifically, damage may manifest, as shown in the case of Beijing Weimeng suing Yunzhilian, by forcing the scraped party to invest additional resources and costs to upgrade anti-scraping technologies to address the threats posed by improper scraping behaviors. This additional operational and maintenance cost not only increases the economic burden on enterprises but may also affect their normal operations due to the time costs and labor costs of technology upgrades. Furthermore, competitive damage may also manifest as an obstruction to the scraped party’s ability to fulfill its contractual obligations to protect user data, which in turn negatively impacts its business reputation. In the digital economy, user data is a crucial asset for businesses and the core of their competitiveness. When a business is unable to protect user data effectively due to unfair competition behaviors, it may not only face legal litigation and fines but, more importantly, lose customer trust and support, thus damaging its business reputation and brand image. More commonly and severely, competitive damage often manifests as the interception of the scraped party’s traffic, even constituting a substantive substitute. This has been fully reflected in classic cases such as Dazhong Dianping suing Baidu, 360 suing Baidu, and Alibaba suing Ma Zhu. In these cases, unfair competition behaviors not only directly deprived the scraped party of business opportunities and profits but also potentially caused long-term and profound damage to its market position and competitiveness by confusing user perceptions and misleading consumer choices. Such damage is not only difficult to measure in monetary terms but may also endanger the survival and development of enterprises.

Finally, in a free competitive market economy, operators do not have the right to demand protection of their market position, customer sources, or business opportunities as absolute rights, shielding them from the invasion of competitors. Rather, they must tolerate some degree of damage as a natural consequence of free competition. Competition is a form of creative destruction, and the advantages gained by one party immediately imply disadvantages for another. The damage caused by competition is neutral; the damage itself does not carry a positive or negative connotation. “Under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, the mere fact that a benefit should be protected does not constitute a sufficient condition for the party suffering from the loss of that benefit to obtain civil relief.” This is the market damage neutrality principle established by the Supreme People’s Court in the Seaweed Quota Case. As seen, what matters is not the damage outcome but the consideration of the legitimacy of the behavior itself, which aligns with the dynamic competition perspective.

4.3. Commercial Ethics Determination

The key to determining the illegitimacy of data scraping behavior lies in whether it violates commercial ethics [16]. However, due to the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty of the concept of commercial ethics itself, its application in judicial practice often becomes a highly controversial issue. When judges handle related cases, they may sometimes unconsciously broaden the scope of commercial ethics, leading to its generalization, which has long been widely criticized by all sectors of society. The generalization of commercial ethics not only may lead to arbitrariness and inconsistency in judicial rulings, but also may interfere with and restrict the normal business operations of enterprises. The complexity and diversity of market competition suggest that the standard of commercial ethics should not be fixed or absolutized. Instead, the existing standards of commercial ethics should be optimized and improved in accordance with Article 3 of the Interpretation by the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of the People’s Republic of China, with the aim of proposing new standards that better align with actual market conditions and judicial practice. These new standards should be clearer and more specific, with stronger recognizability and operability, thereby effectively avoiding the ambiguity and generalization of commercial ethics [17].

Specifically, the new standards should fully consider the actual market competition situation, clearly define the connotations and extensions of commercial ethics, and avoid excessive expansion or contraction. At the same time, the new standards should focus on balancing conflicts of interest between enterprises, protecting the legitimate rights and interests of enterprises, and promoting fair competition and innovative development in the market. Optimizing and improving the standards of commercial ethics can enhance the effectiveness of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law in maintaining market order and promoting the healthy development of enterprises. This, in turn, will provide robust legal protection for the establishment of a fairer, more transparent, and predictable market environment.

4.4. Existing Determination Standards and Their Optimization

4.4.1. Industry Practices

On November 1, 2012, under the organization of the China Internet Association, twelve internet companies signed the Internet Search Engine Service Self-Discipline Convention (referred to as the Self-Discipline Convention), which essentially recognizes and formalizes the behavioral order that had previously been formed and generally observed. Two points need to be optimized:

First, in the case of Dazhong Dianping suing Baidu, the court pointed out that compliance with the robots.txt protocol does not necessarily prove the legitimacy of behavior. Data scraping behavior should be analyzed in two stages: the scraping behavior and the subsequent usage behavior. The robots.txt protocol only addresses whether the data scraping behavior complies with the recognized industry standards, and cannot resolve whether the subsequent usage of the scraped data by the search engine is legal. If the scraping behavior itself violates the robots.txt protocol, the subsequent usage behavior lacks a legitimate basis due to the illegality of the data source. If the scraping behavior complies with the robots.txt protocol, further judgment on the legitimacy of the data scraping behavior should consider other factors, such as whether the amount of data scraped is sufficiently large and valuable, and whether the subsequent usage behavior by the defendant constitutes substantial substitution for the platform that owns the scraped data [18].

Second, the Self-Discipline Convention does not clarify what kind of robots.txt setup constitutes legitimate commercial ethics. It merely broadly requires that the use of robots.txt to restrict search engine scraping should have industry-recognized legitimate and reasonable reasons, and should not violate the principles of fairness, openness, and the promotion of free information flow. However, industry practices can vary, and they may become tools for monopolistic power. Therefore, such practices are still subjects that need to be examined and cannot be considered impartial and objective standards. They require the courts to review their legality.

4.4.2. “Free-Riding”

The behavior of “free-riding” is widely recognized in judicial practice as a violation of commercial ethics. However, there is a tendency in current practice to oversimplify and generalize this concept [19]. A superficial application of intuitive judgment standards such as “free-riding,” “reaping without sowing,” “benefiting from others’ work,” or “plowing others’ fields with someone else’s ox” leads to simple and shallow logic. This not only hinders the establishment of legitimate market expectations regarding commercial ethics but may also cause operators to frequently violate the law, significantly narrowing the space for free competition. To avoid the issues arising from improper information protection, it is necessary to strengthen the review process in specific cases. This requires careful consideration of whether information should be protected, how it should be protected, and how the protection method can align with the essential characteristics and operational rules of the market while minimizing market costs. Such an approach will promote the maximization of market competition value. These deeper considerations are essential for accurately determining the legitimacy of competitive behavior. Only by carefully evaluating these factors can a more precise judgment on the legitimacy of competitive behavior be made, ensuring fair, just, and efficient market competition, and providing a strong foundation for the sustainable and healthy development of the economy.

4.4.3. Introducing New Determination Standards: Objective Market Economic Efficiency and the Proportionality Principle of Interest Balancing

4.4.3.1. Objective Market Economic Efficiency

Returning to the competition law orientation, it is necessary to eliminate non-economic goals in determining the legitimacy of competitive behavior, particularly by shaping commercial ethics standards based on economic objectives. In market transactions, operators are naturally profit-driven, and all market competition behavior is aimed at seeking competitive benefits [20]. On one hand, to ensure that free competition and efficiency in the market economy are fully realized, it is essential to promote the effective functioning of market mechanisms and the optimal allocation of resources. On the other hand, to significantly improve the predictability of commercial ethics judgments and enhance the transparency and rationality of business decisions, it is necessary to introduce a set of scientifically rigorous economic analysis standards. The evaluation indicators covered by these economic analysis standards should be comprehensive and specific. Specifically, these indicators should deeply consider the actual disruption caused by competitive behavior to the market order, assess its potential impact on the competitive landscape, and whether there is any unfair competition or monopolistic behavior. At the same time, the analysis should pay attention to the specific impact of competitive behavior on the survival pressures of both plaintiffs and defendants, including changes in market share, fluctuations in operating costs, and variations in profitability. Additionally, the analysis should carefully consider the technical capabilities of the parties involved and the market opportunities they face, evaluating their adaptability and growth potential in the competitive environment.

The impact on consumer interests is also an essential factor, as it is necessary to analyze whether competitive behavior harms consumers’ legitimate rights, such as through price manipulation, information concealment, or negative effects on consumers’ rights to choose, to know, and to fair trade. Based on this, economic analysis should also consider multi-dimensional factors such as business model innovation, technological change, and industry development, to fully evaluate the comprehensive effects of competitive behavior on economic and social development, thus ensuring that economic analysis standards can both maintain fair market competition and promote the sustainable and healthy development of the economy and society.

4.4.3.2. The Proportionality Principle of Interest Balancing

Many disputes arising from unfair competition cases determined under the general provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law stem from the lack of a stable analysis framework that adheres to a complete proportionality principle. In the face of such rights disputes, the solution lies in the hierarchy of rights and the proportionality principle [21]. The proportionality principle is essentially a tool for balancing and coordinating conflicting interests and provides a universally applicable framework for analyzing the legality of behavior, including the “suitability principle,” “necessity principle,” and “proportionality principle” as three sub-principles [22]. The logic of unfair competition determination based on the proportionality principle can transform the principles of good faith and recognized commercial ethics standards into an objective framework for weighing interests based on competition outcomes, eliminating the specialized protection of specific rights, and maximizing the coordination and compatibility of various interests.

The second-instance court’s ruling in the Dazhong Dianping v. Baidu case clearly reflects the analytical context of the three sub-principles of proportionality in its judgment on the legitimacy of behavior. First, regarding suitability, the second-instance court confirmed that Baidu’s use of review information scraped from Dazhong Dianping for Baidu Maps, where users could view consumer reviews when searching for business locations, was an innovative commercial model that, to some extent, enhanced user experience and enriched consumer choice, resulting in positive effects. Second, regarding necessity, the court held that Baidu could have taken a less damaging approach, such as displaying fewer or partial review information, to minimize harm to Dazhong Dianping while still ensuring a basic user experience. Therefore, Baidu’s use of the data exceeded the necessary limit. Third, regarding proportionality, the court found that the positive effects of Baidu’s scraping behavior were disproportionate compared to the damage caused to Dazhong Dianping, as it had substantially replaced Dazhong Dianping’s service. More importantly, such behavior might discourage other market participants from investing in information collection, disrupting the normal industrial ecosystem and negatively affecting the competitive order. If fewer market participants enter this field, consumers will have fewer channels and options to obtain information in the future, which is detrimental to consumer welfare. As Baidu’s scraping behavior failed to meet the requirements of necessity and proportionality, the court ruled it as unfair competition.

5. Judicial Dilemmas and Optimization Paths for the Application of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law in Data Scraping Cases

5.1. Protection Mode Deviation from Anti-Unfair Competition Focus: Seeking a Balance under the Dynamic Competition Perspective

In legal decisions involving data scraping behaviors, the application of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law often tends to adopt a protection mode centered around the concept of rights infringement. This model first emphasizes identifying the data creator, i.e., those who, through considerable labor, resources, and technology, engage in data collection, organization, and analysis. These entities naturally enjoy legal rights to the data they create. This confirmation of rights is not only a recognition and protection of the data creator’s labor achievements but also a key foundation for maintaining market order, facilitating the reasonable flow and utilization of data resources. On this basis, when these rights are infringed upon due to illegal data scraping activities, the law grants victims clear avenues for relief, including but not limited to demands for cessation of infringement, compensation for losses, etc. This serves as a legal sanction and correction of unfair competition behaviors, ensuring a fair competitive environment in the data market and promoting the healthy development of the data economy. However, this static, linear, and overly simplistic protection mode, which violates the principle of competition damage neutrality, actually contradicts the dynamic competition view. In a free market economy, competition should be viewed as a process where competitors fiercely vie for business opportunities, leading to frequent technological innovations, business model upgrades, improved consumer welfare, and an evolving competitive order [23].

Therefore, the appropriate direction is to return to the competitive law attributes of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, realizing a regulatory model based on the dynamic competition view. The focus should shift to assessing the legitimacy of behaviors. The essence of data scraping is utilizing the results of others’ work. While some scraping may be legitimate, its legality should be judged based on whether it exceeds reasonable limits. This requires case-by-case judgment, fully considering factors such as the volume of data scraped, the types of data involved, and the operational and maintenance costs caused by the scraping behavior [24].

5.2. Data Scraping Judgment Focuses on Rights Protection, But the Core of Anti-Unfair Competition Should Be Maintaining Competitive Balance

The legal judgments in data scraping cases often adopt an infringement-based tort law mindset, inevitably leading to the determination of a protected legal right, followed by an inference of illegitimacy based on the damage to that right. This process typically results in symbolic or ritualistic discussions of the legitimacy of the behavior itself, without substantial consideration of the elements that determine its legitimacy. Courts have even developed a specialized “Non-Interference Principle for Non-Public Interest Necessity,” emphasizing that, unless based on public interest, the commercial interests of prior market participants should not be harmed, which has become a widely applied judicial rule. This effectively elevates the commercial benefits derived from competitors’ advantages to a protected right.

However, the core goal of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law is fundamentally to maintain a healthy and fair market competition environment, focusing on protecting the competition process itself—the dynamic balance of the market—rather than merely protecting specific competitors. The law aims to define reasonable boundaries for competitive property rights, preventing them from being improperly expanded or abused and turning into highly exclusive absolute rights. In this process, the law requires a detailed evaluation of the legitimacy of various market behaviors, considering the interests of multiple stakeholders, including consumers, small and medium enterprises, innovation incentives, and overall market efficiency. This balancing mechanism ensures that the Anti-Unfair Competition Law promotes fair competition while also facilitating market vitality and sustainable development, creating a competitive stage that is both challenging and full of opportunities for various market participants.

5.3. Moralization of Evaluation Deviates from Anti-Unfair Competition Focus: Seeking Legitimacy Balance Under the Efficiency and Benefit Perspective

Emphasizing the importance of data circulation lies in processing the data obtained and enabling its re-utilization [25]. In the legal rulings of data scraping cases, whether the behavior violates business ethics is the foundation for judging legitimacy. However, the widespread use of moral evaluation has often led to overgeneralized individual case judgments by judges. The most prominent example is the creation of judicial principles such as the “Substantial Substitution Principle,” “Minimal Harm Principle,” “Non-Interference Principle for Non-Public Interest Necessity,” and “Legitimate Business Models.” The Substantial Substitution Rule, which has become one of the basic rules for judging the legitimacy of data scraping behavior after more than a decade of development, can be misleading, especially when abstracted into various normative documents, where the issue becomes particularly evident. The Substantial Substitution Rule fundamentally emphasizes direct competition, which contradicts the trend in the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of downplaying competitive relationships and provides no substantial explanation for the legitimacy of the behavior [13]. This fails to offer market participants reasonable expectations.

Introducing objective market efficiency standards and the proportional principle of benefit balance into the recognition of business ethics not only adapts to the flexibility of ethical clauses but also transforms moral standards into an objective framework for weighing interests based on competition effects. This approach maximizes the coordination and compatibility of various interests. As the data market develops and business behaviors related to data utilization become more diversified, there will inevitably be data usage behaviors that benefit competition efficiency and consumer welfare. At that point, the advantages of economic efficiency and benefit assessment standards will become more pronounced, protecting these behaviors from criticism under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

5.4. Paternalistic Intervention Deviates from the Essence of Competition: Seeking a Balance in Economic Law Under the Dynamic Market Perspective

In the judicial decisions of data scraping cases, some judges display a paternalistic intervention tendency. While this is ostensibly done in the name of maintaining competitive order, in practice, it impedes competition. Judges often lean toward excessively protecting specific competitors, constructing exclusionary barriers through legal means, and improperly restricting the competitive freedom of non-specific market participants, thus deviating from the fundamental requirement of market competition. Such practices not only fail to adhere to the essence of competitive thinking—promoting market efficiency and resource allocation optimization through free competition—but also run counter to the dynamic and diverse nature of market competition [26]. Excessive judicial intervention may suppress innovation and technological progress, as well as decrease market vitality and resource allocation efficiency.

In reality, economic law, in its construction and operation, should maintain a necessary modesty and restraint, recognizing the decisive role of market mechanisms in resource allocation and avoiding hasty resort to state intervention. Economic law should be positioned as a supplementary and last-resort tool, intervening only when the market mechanism fails or cannot effectively address specific market issues. This ensures that economic law does not excessively intervene in market operations and prevents the emergence of “excessive interventionism,” avoiding unnecessary control over every minute detail of economic activity. Based on this philosophy, the institutional design of economic law is deeply rooted in the legal principle of “freedom unless prohibited by law.” This principle emphasizes that individuals and businesses should enjoy sufficient freedom to pursue their economic interests unless explicitly prohibited by law. Economic law ensures fair competition by precisely defining the boundaries of unfair competition behavior, while also providing ample space for innovation and market vitality. Economic law only intervenes when significant damage to market order occurs that cannot be overcome or regulated by the market mechanism, aiming to restore the healthy functioning of the market.

This institutional design ensures that economic law maintains market order while not suppressing the competitive freedom and innovative spirit of businesses, thereby providing a solid legal foundation for the prosperity and development of the market economy.

6. Conclusion

This paper, through empirical examination of 27 data scraping case judgments, explores the regulatory effects and practical challenges of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law concerning data scraping behavior. The research finds that in recent years, data scraping cases have mainly occurred in economically developed regions, with the primary case types being counterfeit disputes and online unfair competition disputes. In judicial practice, courts generally adopt the Anti-Unfair Competition Law as the legal basis for regulating data scraping and its subsequent applications. The core focus is to determine whether the behavior is deemed unjust under the competition law framework. At the same time, the judicial community has moderately expanded the criteria for identifying competitive relationships, no longer limiting it to the traditional notion of direct competition.

In judging the legitimacy of data scraping behavior, courts face many difficulties. On the one hand, business ethics standards are somewhat ambiguous, leading to the potential for overgeneralization or inconsistency in individual case judgments. On the other hand, data scraping behaviors often involve complex balancing of interests, including the interests of data controllers, non-data controllers, consumers, and other market competitors. Therefore, when assessing the legitimacy of such behavior, courts must fully consider the dynamic and diverse nature of market competition, as well as the effects on market competition order, consumer welfare, and industry development.

In conclusion, the Anti-Unfair Competition Law has played an important role in regulating data scraping behaviors but still faces many challenges. In the future, there is a need to further optimize the regulatory approach of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, introducing more objective and quantifiable standards of judgment to enhance judicial accuracy and predictability, thereby promoting the healthy development of the data market.

References

[1]. Li, H., & Sun, J. (2018). On the legal boundaries of web scraping data behavior. Electronic Intellectual Property, 12.

[2]. Ding, X. (2019). Who owns the data? — A look at platform data ownership and data protection from the perspective of web crawlers. Journal of East China University of Political Science and Law, 5.

[3]. Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd. v. Yunzhilian Network Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd. (2017). Civil judgment (2017) Jing 0108 Minchu 24512, Beijing Haidian District People’s Court.

[4]. A certain computer system company, a certain technology (Shenzhen) company v. a certain technology company (Hangzhou) (2021). Civil judgment (2021) Zhe 8601 Minchu 309, Hangzhou Railway Transport Court.

[5]. Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd. v. Shanghai Fuyu Culture Communication Co., Ltd. (2017). Civil judgment (2017) Jing 0108 Minchu 24510, Beijing Haidian District People’s Court.

[6]. Jiang, G. (2019). Reflection and interpretation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law’s network provisions: Focusing on the principle of typification. Chinese and Foreign Legal Studies, 1.

[7]. Hangzhou Alibaba Advertising Co., Ltd., Alibaba (China) Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. v. Nanjing Mazhu Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. (2019). Civil judgment (2019) Zhe 0108 Minchu 5049, Binjiang District People’s Court, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

[8]. Yang, H., & Qu, S. (2013). On the legal nature of web scraper agreements. Application of Law, 4.

[9]. Feng, B., & Zhang, J. (2023). Economic logic and judicial connection of Antitrust Law and Anti-Unfair Competition Law in the digital platform field. Legal Studies, 3.

[10]. Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Co., Ltd., Tencent Technology (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd., et al. v. Zhejiang Soudao Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. (2019). Civil judgment No. 1987, Zhe 8601 Minchu, Hangzhou Railway Transport Court.

[11]. Zhang, S. (2023). On the Anti-Unfair Competition Law protection of data sets. Journal of Henan University of Economics and Law, 5.

[12]. Li, Z. (2021). Reflections and revisions on the regulation of data crawling behavior from the perspective of Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Journal of Jinan University, 6.

[13]. Shen, G., & Liu, Y. (2021). The regulatory dilemma and solutions for data crawling behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. China Circulation Economy, 1.

[14]. Gao, J. (2024). Legality of data crawling behavior from the perspective of competition law. Journal of Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, 1.

[15]. Li, J. (2024). Judging the legitimacy of data crawling behavior: Reflecting on the substantial substitution rule. Journal of Political and Legal Studies, 2.

[16]. Yang, H. (2014). The impact of crawler agreements on internet competition relationships. Intellectual Property, 1.

[17]. Fan, C. (2015). Industry practices and unfair competition. Jurist, 5.

[18]. Yao, J. (2019). Guidelines for the use of corporate data. Tsinghua Law Review, 3.

[19]. Chen, G. (2023). A theoretical critique and rule improvement on the expansion of general provisions under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Legal Studies, 1.

[20]. Lin, L., & Zhang, Z. (2003). On the hierarchy of rights in conflicts of rights: An analysis from the perspective of normative jurisprudence. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 5.

[21]. Sollen, L. (2010). Legal lexicon: A toolbox for law school students (Wang, L. H., Trans.). China University of Political Science and Law Press. (Original work published 2010).

[22]. Cai, C. (2021). The regulation of data crawling behavior in competition law. Comparative Law Studies, 4.

[23]. Li, J. (2024). Judging the legitimacy of data crawling behavior. Journal of Political and Legal Studies, 2.

[24]. Xu, K. (2021). The legitimacy and boundaries of data scraping. China Law Studies, 2.

[25]. Zhang, P. (2013). The general provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and its application: Reflections on crawler agreements in search engines. Application of Law, 3.

Cite this article

Chen,J. (2025). Empirical study on the regulation of data crawling behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(2),1-11.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Li, H., & Sun, J. (2018). On the legal boundaries of web scraping data behavior. Electronic Intellectual Property, 12.

[2]. Ding, X. (2019). Who owns the data? — A look at platform data ownership and data protection from the perspective of web crawlers. Journal of East China University of Political Science and Law, 5.

[3]. Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd. v. Yunzhilian Network Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd. (2017). Civil judgment (2017) Jing 0108 Minchu 24512, Beijing Haidian District People’s Court.

[4]. A certain computer system company, a certain technology (Shenzhen) company v. a certain technology company (Hangzhou) (2021). Civil judgment (2021) Zhe 8601 Minchu 309, Hangzhou Railway Transport Court.

[5]. Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd. v. Shanghai Fuyu Culture Communication Co., Ltd. (2017). Civil judgment (2017) Jing 0108 Minchu 24510, Beijing Haidian District People’s Court.

[6]. Jiang, G. (2019). Reflection and interpretation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law’s network provisions: Focusing on the principle of typification. Chinese and Foreign Legal Studies, 1.

[7]. Hangzhou Alibaba Advertising Co., Ltd., Alibaba (China) Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. v. Nanjing Mazhu Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. (2019). Civil judgment (2019) Zhe 0108 Minchu 5049, Binjiang District People’s Court, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

[8]. Yang, H., & Qu, S. (2013). On the legal nature of web scraper agreements. Application of Law, 4.

[9]. Feng, B., & Zhang, J. (2023). Economic logic and judicial connection of Antitrust Law and Anti-Unfair Competition Law in the digital platform field. Legal Studies, 3.

[10]. Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Co., Ltd., Tencent Technology (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd., et al. v. Zhejiang Soudao Network Technology Co., Ltd., et al. (2019). Civil judgment No. 1987, Zhe 8601 Minchu, Hangzhou Railway Transport Court.

[11]. Zhang, S. (2023). On the Anti-Unfair Competition Law protection of data sets. Journal of Henan University of Economics and Law, 5.

[12]. Li, Z. (2021). Reflections and revisions on the regulation of data crawling behavior from the perspective of Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Journal of Jinan University, 6.

[13]. Shen, G., & Liu, Y. (2021). The regulatory dilemma and solutions for data crawling behavior under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. China Circulation Economy, 1.

[14]. Gao, J. (2024). Legality of data crawling behavior from the perspective of competition law. Journal of Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, 1.

[15]. Li, J. (2024). Judging the legitimacy of data crawling behavior: Reflecting on the substantial substitution rule. Journal of Political and Legal Studies, 2.

[16]. Yang, H. (2014). The impact of crawler agreements on internet competition relationships. Intellectual Property, 1.

[17]. Fan, C. (2015). Industry practices and unfair competition. Jurist, 5.

[18]. Yao, J. (2019). Guidelines for the use of corporate data. Tsinghua Law Review, 3.

[19]. Chen, G. (2023). A theoretical critique and rule improvement on the expansion of general provisions under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Legal Studies, 1.

[20]. Lin, L., & Zhang, Z. (2003). On the hierarchy of rights in conflicts of rights: An analysis from the perspective of normative jurisprudence. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 5.

[21]. Sollen, L. (2010). Legal lexicon: A toolbox for law school students (Wang, L. H., Trans.). China University of Political Science and Law Press. (Original work published 2010).

[22]. Cai, C. (2021). The regulation of data crawling behavior in competition law. Comparative Law Studies, 4.

[23]. Li, J. (2024). Judging the legitimacy of data crawling behavior. Journal of Political and Legal Studies, 2.

[24]. Xu, K. (2021). The legitimacy and boundaries of data scraping. China Law Studies, 2.

[25]. Zhang, P. (2013). The general provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and its application: Reflections on crawler agreements in search engines. Application of Law, 3.