1. Introduction

As the international situation is becoming increasingly complex, the BRICS member states, as representatives of developing and emerging market countries, also face opportunities and challenges in deepening comprehensive cooperation. Looking back, the BRICS countries have achieved notable progress in strengthening institutional mechanisms, conducting multi-sector exchanges, and increasing foreign investment. At present, the BRICS are entering their second “golden decade,” having evolved from the “BRICS four” to the “BRICS five,” and progressing toward the “BRICS ten,” marking a further deepening of the BRICS cooperation mechanism. Looking ahead, in the face of the ever-changing international situation, it is necessary to continue to consolidate the “three-pillars framework” of political and security cooperation, economic and trade cooperation, and people-to-people and cultural exchanges; to promote civil society interactions; to encourage cooperation among civil society organizations; and to strengthen mutual understanding.

Strengthening public support and deepening mutual understanding among the peoples of different countries are the foundations for advancing cooperation and exchanges across various fields. For BRICS cooperation, the core of the “collective region” should not be limited to economic and trade interests, but should be fundamentally rooted in “people-to-people connectivity and political mutual trust.” Accordingly, seeking platforms for people-to-people connectivity is of great significance for the sustained development of relations among BRICS countries and can also help promote the advancement of people-to-people and cultural exchanges in step with economic and trade cooperation.

At the BRICS and Developing Countries Civil Society Organizations Forum, representatives from various countries discussed the role of civil society organizations within the BRICS framework, recognizing that their participation is of great significance for promoting BRICS cooperation [1]. In addition, according to data from the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, IPEA) of Brazil, the development of Brazilian civil society organizations has reached a certain scale and exhibits universality and widespread presence across the federal states [2]. From the current state of research, although there have been studies on Brazilian civil society organizations focusing on legal aspects and their internal functions [3], the research on civil society organizations in Brazil is not comprehensive enough.

Based on this, in order to seek a platform for people-to-people connectivity, this study takes Brazilian civil society organizations as its focus. It explores their dual role under the BRICS mechanism from both domestic and international dimensions, considering their key functions in promoting internal stability and external cooperation.

2. The regulatory system and organizational structure of Brazilian civil society organizations

2.1. The legal constraints on Brazilian civil society organizations

Brazilian civil society organizations (Organizações da Sociedade Civil, OSCs) are a concept based on civil society, public interest, and non-profit characteristics. The Constitution of Brazil issued in 1988 provided a prerequisite guarantee for the operation of Brazilian civil society organizations and played a promoting role in developing of civil society organizations. On the one hand, the Constitution effectively guarantees the basic human rights of citizens, standardizes the operation of the country democratic system, raises the overall awareness of democracy, and creates favorable conditions for the formation of civil society organizations.

Article 5 of the Constitution guarantees the basic rights of equality between men and women, freedom of movement, the right to a fair trial, freedom of thought, the right to defense, freedom of conscience and religion, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom to choose one’s occupation, the right to peaceful assembly, and freedom of association [4]. On the other hand, the Constitution provides the fundamental legal basis for the regulated operation and supervision of civil society organizations, ensuring and promoting their social participation. This includes, but is not limited to, provisions regarding whether the state is allowed to interfere in the operation of legally established associations and cooperatives, as well as the necessary judicial procedures for the dissolution of associations and the suspension of their activities. In addition, the “Civil Society Organization Regulatory Framework” explicitly states that most civil society organizations in Brazil emerged after the promulgation of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, which to some extent confirms that the Constitution provides fundamental protection and support for the development of civil society organizations.

Under the guarantee of the Constitution, other laws and regulations have also made corresponding norms on the operation scope, service areas, basic types, and principles of Brazilian civil society organizations. Specifically, in 2014, the Brazilian federal government promulgated the Civil Society Organization Regulatory Framework (MROSC) [5], a regulatory document that defines and standardizes civil society organizations in Brazil. It points out that civil society organization is based on the public interest for non-profit private entities, committed to promoting health, education, culture, science and technology, agricultural development, social assistance and housing, and in the field of rights and activities, and stipulates the regulatory civil society organization in the process of “contract, economic sustainability and certification” three guiding direction. This regulatory framework specifically defines the partnership between the government and civil society organizations and effectively standardizes the guidelines and basic principles of civil society organizations.

The Brazilian government recognizes Civil Society Organizations of Public Interest (Organizações da Sociedade Civil de Interesse Público, OSCIPs) and Social Organizations (Organizações Sociais, OSs) as types of civil society organizations. Once officially certified, these organizations are eligible for preferential policies. Among them, public welfare civil society organizations that meet the qualification requirements can standardize the legal system with government power departments, and non-profit entities that have obtained the qualification of social organizations can not only obtain preferential policies such as government budget distribution and tax relief but also sign management contracts to improve the efficiency of public management. In addition, Law No. 9,790, issued on March 23, 1999, established regulations governing public-interest civil society organizations, and was amended by Law No. 13,019 in 2014. It clearly stipulates the required years of operation, activity criteria, and purpose of action that meet the qualification identification. To sum up, the legal framework governing Brazilian civil society organizations operates under the fundamental protection of the Constitution, complemented by other laws and regulations. Together, they serve as essential tools to ensure the effective and regulated functioning of civil society organizations.

2.2. Identification and classification of Brazilian civil society organizations

The federal government of Brazil has introduced legal regulations regulating civil society organizations, recognizing the three types of Brazilian civil society organizations. First, Non-profit private entities, which do not distribute assets or profits among shareholders, partners, board members, auditors, employees, or donors. Instead, all operational income must be fully reinvested—either directly, through equity funds, or via reserve funds—toward achieving the organization’s non-profit objectives. Second, Cooperatives, as defined by Law No. 9.867 of November 10, 1999, which operate with the aim of providing social assistance, alleviating poverty, creating job opportunities, promoting rural culture, education, technical training, volunteer service, socio-economic development, and safeguarding the public interest in one or more of these areas. Third, Religious organizations that engage in public interest activities or projects, provided their primary purpose is not the promotion of religious belief.

The IPEA of Brazil proposed that the identification of civil society organizations should have the following conditions [6]: (a) private nature, the organization must be legally independent from the state; (b) non-profit orientation, it must not distribute profits among owners or board members and any surplus generated must be fully reinvested into the organization’s activities; (c) legally established, the organization must have legal personality and a valid National Registry of Legal Entities (Cadastro Nacional da Pessoa Jurídica, CNPJ); (d) autonomous management, activities must be independently organized and managed; (e) voluntary formation, the organization must be founded by individuals on a voluntary basis, and its leaders must be free to choose the activities it engages in.

Based on this, the IPEA holds that, according to relevant provisions of the Brazilian Civil Code, there are three types of entities that meet the above five criteria: private associations, private foundations, and religious organizations. At the same time, IPEA argues that whether cooperatives fall under the category of civil society organizations must be determined through a specific legal analysis of their public-interest purposes. Therefore, not all cooperatives can be classified as civil society organizations.

To sum up, to be recognized as a civil society organization in Brazil, an entity must simultaneously meet the conditions of being private, nonprofit, legally established, possessing self-management capability, and exercising independent decision-making based on the principle of voluntariness—referred to as the “three characteristics, one capability, and one principle.” They are divided into three categories: private associations, private foundations, and religious organizations.

2.3. The “network of relationships” of Brazilian civil society organizations

According to the formality of the rights relationship and interaction between the government and non-profit organizations, in a study of the relationship between government and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), Coston proposed eight models of government-NGO relationships. Among them, repression, rivalry, and competition represent “government-dominant” asymmetric power relations that emerge under a government opposition to pluralistic systems. In contrast, contracting, third-party government, cooperation, complementarity, and collaboration reflect symmetrical power relations formed under conditions where the government supports a pluralistic system [7].

Young identified three existing models of the relationship between nonprofit organizations and the government: the supplementary model, the complementary model, and the adversarial model [8]. Specifically, in the supplementary model, based on the diversity of social needs, nonprofit organizations provide services that the government does not offer, thus playing a supplementary role. In the complementary model, nonprofit organizations act as government partners, assisting in the provision of public services. In the adversarial model, there is mutual interaction: nonprofit organizations urge the government to change public policies and are accountable to the public, while the government attempts to influence nonprofit organizations’ behavior by regulating their services and responding to their advocacy initiatives.

According to Najam, the relationship between non-governmental organizations and the government is based on a conceptual framework grounded in the theory of strategic institutional interests, with the two key elements of this framework being strategies and goals [9]. That is, whether the government or non-governmental organizations will achieve their goals through means, but the difference is that the strategy and the goal may be consistent or inconsistent, thus forming a model of “two elements and four forms”. In detail, there are four possible relationship modes between NGOs and the government on specific issues: (a) cooperation mode—the policy goals are consistent, and the preference strategies are consistent; (b) confrontation mode—the policy goals and the preference strategies are inconsistent; (c) complementary mode—consistent policy goals and inconsistent preference strategies; (d) absorption mode—inconsistent policy goals and consistent preference strategies.

In conclusion, Coston divided the relationship between non-profit organizations and the government into two parallel lines pointing in different directions from the perspective of whether the government’s support for the diversified system. Among them, the government supports the diversified system is a necessary condition for the occurrence of the cooperation mode. Young, from the perspective of economic theory, argued that when assessing the complementary relationship between the government and nonprofit organizations, there is a positive correlation between government funding and the scale of activities carried out by nonprofit institutions. From the perspective of strategic institutional interests, Najam believes that the consistency of strategy and goal is the premise of the cooperative relationship between the government and non-profit institutions.

According to the MROSC, the Brazilian federal government believes that social participation is not only crucial to the way of governing, but also to the formulation, implementation, and supervision of public policies, and that civil society organizations play a key role in the process of realizing social participation. In addition, the private and non-profit characteristics of civil society organizations promote the development of Public-Private Partnership with government departments, and the government can provide funds to them, thus forming a virtuous cycle of interaction and resource complementarity, and realizing a “win-win” situation. It can be seen that there is an obvious and close partnership between the Brazilian government and civil society organizations.

3. Development trends of civil society organizations in Brazil

The IPEA has been tracking the development data of civil society organizations. According to the latest statistics released in 2024, the number of Brazilian civil society organizations has increased to 879 326 by 2023, an increase of 7.8% over 2021 [10]. The number of civil society organizations in Brazil was 815 677 in 2021, and the number of new civil society organizations reached 24 000 in 2020, about double the number added in 2019 [11]. It can be seen from the statistical results that, from the macro perspective, the overall development momentum of the civil society organizations in Brazil has momentum. At the same time, it is necessary to analyze their development trend from the micro perspective of regional distribution, per capita ratio, and sectoral distribution.

3.1. The universality and concentration of the regional distribution

From the perspective of regional distribution, the distribution of civil society organizations has the characteristics of universality and concentration. Civil society organizations are established in the federal states and cities/towns of Brazil, which are extensive, but the differences between cities/towns are obvious, among which the largest number of civil society organizations is São Paulo, with 55 000. In terms of regional proportion, civil society organizations are concentrated in the southeast of Brazil, accounting for 41.5% in 2021, while there are fewer civil organizations in the North, accounting for 7% [11]. In terms of increase, the Midwest and North increased the most from 2021 to 2023, reaching 11% and 9.9% respectively, followed by the Southeast and Northeast with 8.1% and 7.1% respectively, and the South with the smallest increase of 5.9%.

3.2. The difference in the per capita ratio

From the perspective of the per capita ratio, the ratio of civil society organizations in different regions shows certain differences. Based on the statistical data from the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service (Secretaria da Receita Federal do Brasil, SRF) and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE), the average number of civil society organizations per thousand people in the north, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Midwest in 2016 was 3.8, 3.6, 3.8, 5.4 and 4.1 respectively [6]. Compared with the regional per capita ratio in 2023, although the per capita ratio in the southeast increased significantly, other regions did not show significant differences. It can be seen that in the regional distribution of civil society organizations in Brazil, the per capita ratio in southern regions is significantly higher than that in other regions (see Table 1).

|

2016 |

2023 |

|||||

|

Number of civil society organizations |

Population |

Per capita ratio (per thousand people) |

Number of civil society organizations |

Population [12] |

Per capita ratio (per thousand people) |

|

|

North |

67,370 |

17,707,783 |

3.80 |

64,717 |

17,349,619 |

3.73 |

|

Northeast |

205,300 |

56,915,936 |

3.61 |

215,636 |

54,644,582 |

3.95 |

|

Southeast |

325,376 |

86,356,952 |

3.77 |

366,000 |

84,847,187 |

4.31 |

|

South |

157,898 |

29,439,773 |

5.36 |

158,696 |

29,933,315 |

5.3 |

|

Midwest |

64,242 |

15,660,988 |

4.1 |

74,241 |

16,287,809 |

4.56 |

3.3. The tendencies in sectoral distribution

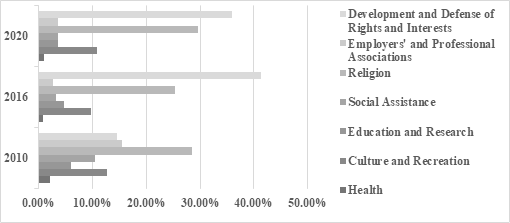

From the perspective of sectoral distribution, the service areas of civil society organizations show a certain degree of tendency or concentration. The activities of Brazilian civil society organizations mainly include health, entertainment, education and research, social assistance, religion, professional associations, and the development and maintenance of rights and interests. Data was tracked by the services of the IBGE, the SRF, and the IPEA [6]. According to the statistical results, on the whole, the development of civil society organizations is concentrated on the development and maintenance of rights and interests, religion, culture, and entertainment, while the proportion of services in the health field accounts for a tiny proportion. In terms of the performance of different years, in 2010, civil society organizations serving the religious sector accounted for a relatively large proportion, reaching 28.5%. According to the data in 2016 and 2020, civil society organizations have a certain service tendency in the development and maintenance of rights and interests, reaching 41.3% and 35.9% respectively. At the same time, the activities of civil social organizations in the field of social assistance showed a significant decline, from 10.5% in 2010 to 3.3% in 2016, compared with 3.6% in 2020 (see Figure 1).

From the perspective of development, there are some differences in the development trend of civil society organizations in different service fields, among which social assistance, education, and research show a declining trend. Although the ranking of civil society organizations in the field of entertainment in various sectors has decreased, the proportion in the sector of entertainment is relatively stable, with little fluctuation, and maintained at the level of 10%.

From the above three fundamental summaries, a large number of Brazilian civil society organizations are concentrated in the southeast, with the highest per capita ratio in the southern region. The service sector is diversified. At the same time, they have the development and maintenance of rights and interests and religious services, so there are some difficulties in the development of the health sector. When looking for cooperation opportunities among BRICS countries from the level of civil society organizations, it is necessary to consider the development status and general trend of civil society organizations in Brazil and choose the cooperation direction of civil society organizations from the stability and tendency.

4. The key role of civil society organizations under the BRICS mechanism

Since the establishment of the BRICS Cooperation mechanism, cooperation among member states has covered a wide range of areas and diversified forms. A multi-field and multi-level cooperation framework has been formed, guided by leaders’ summits and supported by ministerial-level meetings such as senior officials’ meetings on security affairs and foreign ministers’ meetings [14]. With the deepening of BRICS cooperation, civil society organizations have gradually participated in and interacted in different fields and played an irreplaceable role based on the characteristics of non-profit, self-management, and self-determination.

4.1. Civil society organizations shall participate in government decision-making and state governance

Based on the experience of civil society participation in government decision-making, the Brazilian National Integration Network (REBRIP) put forward the establishment of the BRICS Civil Society Forum, believing that its participation in governance can improve political legitimacy, get closer to the requirements and needs of citizens, more effectively regulate conflicts, and is conducive to optimizing the democratic environment. Brazil has been more active in civil society engagement, both global and regional. Since its establishment, the BRICS Civil Society Forum has played a key role in promoting information exchange and dialogue among BRICS countries, strengthening connections between civil society organizations of the member states, and providing advice to BRICS leaders.

BRICS civil society organizations participate in governance through exchanges and dialogue with the New Development Bank. According to the information released by the Beijing Green Research Public Welfare Development Center, in October 2017, representatives of civil society organizations from BRICS countries engaged in discussions with the BRICS New Development Bank on topics such as environmental issues, climate change, energy transition, women’s rights, and sustainable development [15]. During the communication, civil society organizations raised questions about the relevant policies of the New Development Bank, and put forward suggestions regarding language settings, timeframes, and the public environment for social evaluations. In addition, civil society organizations also expressed their views and concerns on referring to national standards, environmental and social frameworks, attitudes towards thermal power, and gender equality. From this perspective, this activity reflects the good form of interaction between the BRICS civil society organizations and the New Development Bank and also the cooperation model of “consistent policy goals and consistent preference strategies”.

4.2. Civil society organizations to promote close ties and common progress among BRICS members

The BRICS civil society organizations will strengthen the ties between the civil society organizations of their member states, stabilize the BRICS relations and jointly address various challenges. At the opening ceremony of the 2021 BRICS Civil Forum, Sanjay Bhattacharyya, Secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs of India, stated that interaction among civil society organizations of BRICS countries would become a beacon for the advancement of the BRICS cooperation mechanism. He emphasized that civil society represents the collective conscience of the people, and its voice is becoming increasingly important in responding to the trends of the times, addressing global climate change, demographic shifts, and challenges to the multilateral trading system [16].

Therefore, it is necessary to promote the establishment of an international order for common progress, including the participation of individuals, civil society, national, and multilateral forums. According to information released by the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), the agenda of the 2021 BRICS Civil Forum covered a wide range of areas including politics, economy, health, and education. Specific topics included reformed multilateralism, finance and development, global public goods, the response strategies and roles of civil society organizations during the pandemic, dialogue on health and traditional medicine systems among BRICS countries, women’s development, economic growth, and education [17]. In addition, the BRICS civil society organizations are uniting and also play an important role in fighting the epidemic. According to a report by China Daily, at the 2022 seminar titled “Strengthening Public Health Cooperation and Joining Forces to Combat the Pandemic among BRICS civil society organizations”, a representative from Doctors Without Borders proposed that BRICS countries should strengthen cooperation and exchange in various scientific fields [18].

BRICS civil society organizations have always pursued the concept of unity and sustainable development to promote the common progress of BRICS countries. The BRICS Political Parties, Think Tanks, and Civil Society Organizations Forum held in May 2022 was themed “unity and cooperation to promote development, hand in hand towards a better future.” The forum highlighted the vital role of BRICS countries in pandemic response, economic recovery, and global governance, and emphasized the responsibilities of political parties, think tanks, and civil society organizations within the BRICS framework. The joint initiative stated that “civil society organizations should serve as important platforms for enhancing mutual understanding, deepening friendship, strengthening cooperation, and promoting coordination among the peoples of BRICS countries [19].” BRICS civil society organizations can play an important role in enhancing political mutual trust, deepening understanding among member states, strengthening the sense of community among BRICS countries, and promoting consensus on international issues.

5. The dual role of civil society organizations in Brazil under the BRICS mechanism

5.1. The continuous role and importance of ensuring internal stability in Brazil

The development of NGOs in Brazil can be traced back to the 1950s, with the earliest organizations characterized by strong religious affiliations. One of the earliest examples was the Basic Ecclesial Communities, which emerged during the Cold War and carried out activities closely linked to Catholicism, serving ordinary people in times of hardship.

Then, in the 1970s, as social movements began to proliferate, the service areas of NGOs in Brazil started to diversify across multiple sectors. A notable example is the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, MST), which emerged in the broader context of agrarian reform in Brazil. This organization arose in response to the economic crisis and rapid industrialization, advocating for land reform, defending the rights of rural workers, and opposing the military dictatorship. It adopted nonviolent methods to call on the government to address the deep inequality caused by extreme land concentration.

Importantly, the MST also established a mutually beneficial relationship with the market, securing rights for rural “workers” and helping to alleviate some of the negative impacts of urbanization.

The National Union of Students (União Nacional dos Estudantes, UNE) is one of the most important student organizations in Brazil and also one of the longest-standing civil society organizations in the country. It has witnessed the nation’s ongoing development and continuous transformation, playing a significant role at various historical turning points. According to the relevant information of the Brazilian Senate [20], the UNE emerged from the student movement and has since actively participated in various social activities. During World War II, it opposed Nazi fascism and pressured the Vargas government to take a clear stance and join the anti-fascist war effort, confronting the Axis powers.

During the same period, the Vargas government issued a decree officially recognizing the UNE as the representative organization of university students. Following the end of World War II and the collapse of Vargas’s authoritarian “Estado Novo” regime, the UNE played an important role in the popular “The Oil is Ours” campaign.

After the military regime came to power, the UNE was subject to constant repression and disruption by the military dictatorship. More severely, the government passed legislation that stripped the organization of its representative status. Although it remained active in protests against authoritarian rule, the UNE entered a difficult period of sustained suppression.

With the end of the military regime, the UNE returned to the public stage, voicing its stance on constitutional reform and political democratization, and defending the fundamental interests of the nation and its people. From the perspective of historical change and political transition, a qualitative analysis of the UNE reveals that Brazilian civil society organizations have served as accompanying forces in times of historical transformation, protectors of the basic rights of the people, and catalysts for the realization of national political democracy.

From the perspective of the relationship between Brazilian civil society organizations and the state, it is evident that during both the Vargas dictatorship and the military regime, this relationship was largely characterized by a confrontational model. In other words, the policy goals and strategic preferences of the government and civil society organizations were fundamentally misaligned. Civil organizations that sought to defend political democracy were repeatedly repressed, which had a significant negative impact on their growth in scale and level of social participation. After the end of the military regime in the 1990s, the relationship between the two shifted from confrontation to cooperation. Brazilian civil society organizations experienced large-scale development and began to interact more closely with the state. On the one hand, Brazilian civil society organizations can monitor and promote national development and political democracy through social participation. On the other hand, democratic politics created a favorable environment for the civil society organizations development and provided fundamental policy support for social participation.

From the late 20th century to the early 21st century, Brazilian civil society organizations developed rapidly and expanded into an increasing number of sectors. However, overall, they remained relatively small in scale and exhibited low levels of social participation. With continuous expansion in scale and diversification of service areas, Brazilian civil society organizations have gradually extended their social service activities to sectors such as social assistance, health, education, and culture [21].

Among these, it is worth highlighting that social assistance is an important area of participatory cooperation between Brazilian civil society organizations and federal, state, and municipal governments. Since 2006, the “Unified Social Assistance System” (Sistema Único de Assistência Social, SUAS) has been implemented as a public system dedicated to organizing social assistance services. It not only provides plans, services, and benefits to individuals or families in socially vulnerable situations, but also protects the fundamental rights of individuals or families at risk [22]. In addition, it can play an active role in responding to social emergencies. More importantly, under the implementation of the SUAS system, Brazilian civil society organizations participate as co-managers in local social assistance councils, sharing responsibility for safeguarding citizens’ rights to social protection [23]. This participatory cooperation in co-management thus serves as a guarantee for maintaining social stability and equal rights.

The Regulatory Framework for Civil Society Organizations notes that, based on the shift from representative democracy to participatory democracy, the participation of civil society organizations in various work in the public policy cycle plays a key role in solving complex social problems. Compared with the government control mode, the participatory cooperation of joint management helps to form a stable situation, play the role of mutual supervision, and avoid the corruption that personal interests harm the interests of the people.

Internally, Brazil has a series of social problems such as uneven distribution of resources, increasing gap between the rich and the poor, economic downturn, rapid urbanization, and high crime rate among young people. In this regard, Brazilian civil society organizations play an important role in building an equal, free, democratic, safe, and harmonious social environment. The participation and cooperation between civil society organizations and the government not only promote the realization of a harmonious society where national political democracy and everyone is equal before the law but also enhance the importance and ability of civil society organizations. In addition, under the BRICS mechanism, the participation, interaction, and advocacy of Brazilian civil society organizations can deepen member countries’ understanding of Brazil itself, as well as clarify Brazil’s needs and current situation in relevant fields, thereby safeguarding the country’s fundamental interests.

5.2. The promoting role and importance of the BRICS mechanism

Since the establishment of the BRICS cooperation mechanism, relations among member countries have developed across various dimensions, and their connections have become increasingly close. As the number of BRICS member states continues to grow, economic and trade cooperation among member states has been strengthened, promoting political and security cooperation and people-to-people and cultural exchanges.

At the same time, it is important to pay attention to the balanced development of cooperation across different fields to avoid the “weakest link” effect. Specifically, economic cooperation and trade exchanges have been the starting point and main focus of BRICS countries’ collaboration and development. However, there are differences in people-to-people and cultural exchanges among member states. In comparison, the people-to-people and cultural exchanges between China and Russia are relatively mature.

Although China and Brazil have not established a high-level mechanism for people-to-people and cultural exchanges, such activities have been ongoing. Paragraph 63 of the Ufa Declaration of the Seventh BRICS Summit explicitly proposed the initiative to support the establishment of the BRICS University League, aiming to create a platform for cooperation and exchange in the field of education among BRICS countries [24]. In 2019, the China-Brazil Football Exchange Center was established to promote exchanges between the two countries in the field of football [25]. In addition to enhancing people-to-people and cultural exchanges through investment, talent development, and football-related cooperation, the collaboration between local cities in China and Brazil has also been steadily advancing. In 2021, the Chongqing municipal government and the State of São Paulo, Brazil, held a thematic seminar on “Co-building Smart Cities” [26]. The seminar has deepened our mutual understanding and provided a platform for communication and exchange in the field of scientific and technological innovation. In the same year, Mianyang City of China and Niterói City of Brazil established a friendly cooperative relationship and proposed to focus on exchanges and cooperation in the fields such as pandemic response, telemedicine, culture and education, and science and technology [27].

It can be seen that the Brazilian government has demonstrated a certain level of enthusiasm for people-to-people and cultural exchanges and cooperation, made some efforts, and achieved notable results. This not only plays a positive role in fostering a participatory cooperation model between Brazilian civil society organizations and the government but also provides support for civil society organizations’ involvement in such activities under the BRICS mechanism, thereby promoting deeper people-to-people and cultural exchanges and cooperation among member countries within the BRICS framework.

It is worth noting that the Brazil-China Chamber of Commerce, building on the foundation of economic and trade cooperation between China and Brazil, has continuously expanded the scope of social participation through social services and various public welfare initiatives. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chamber provided the first batch of protective supplies to Aricanduva Park and, following the outbreak in Brazil, organized member institutions to donate supplies and facilitated remote meetings for experts from both countries to share medical treatment experiences [28]. This series of social activities serves as a powerful driving force for fostering mutual understanding and close ties between the peoples of China and Brazil.

In fact, the participation and interaction of civil society organizations in different fields under the BRICS cooperation mechanism not only represents the national interests but also expresses the common voice of the civil society of the BRICS countries. Civil society organizations also play an important role in participating in global governance. From this perspective, as a member of the BRICS countries, Brazil’s civil society organizations can also play an active role in promoting exchanges among BRICS countries. Externally, Brazilian civil society organizations can positively influence multilateral cooperation under the BRICS mechanism, contributing to the advancement of economic and trade cooperation, the promotion of people-to-people and cultural exchanges, and the strengthening of mutual understanding among the peoples.

6. Feasibility suggestions and prospects

To promote the continuous stability of political and security cooperation, economic and trade cooperation, and people-to-people and cultural exchanges under the BRICS mechanism, and “the high-quality development of greater BRICS cooperation” [29], it is necessary to think about how to play the role of civil society organizations. A relatively stable and cooperative cooperation model has been formed between Brazilian civil society organizations and the government, which provides a prerequisite for civil society organizations to play a role in the BRICS mechanism. From the perspective of duration, the development of civil society organizations in Brazil is relatively mature, which plays an important role in maintaining national stability, promoting social harmony, and realizing democracy and equality. More importantly, driven by the participatory cooperation model, Brazilian civil society organizations have also played a role in promoting exchanges in different areas of the BRICS mechanism.

From Brazil’s civil society organization management mechanism, development trend, and role positioning, strengthening the mechanism of the BRICS and Brazilian civil society organizations in the rights and interests development and maintenance, cultural exchanges can find a new breakthrough point for cooperation between countries, or find a breakthrough point to realize the balanced development in various fields, break the bottleneck of people-to-people and cultural exchanges, broaden the breadth and increase the depth of cooperation under the BRICS mechanism. From the current state of development, although Brazilian civil society organizations have shown relatively low levels of participation in the health sector, the deepening of global health governance cooperation will inevitably make this area a key focus for their engagement. It will enable these organizations to contribute more actively to addressing health challenges among BRICS countries and to advancing the achievement of global health goals.

Acknowledgement

This paper is the achievement of the “3146” multilingual high-level international talent training project of Sichuan International Studies University. It is also part of the research project titled “The Role and Development Status of Brazilian Civil Society Organizations under the BRICS Mechanism,” conducted by the Chongqing Institute of International Strategic Studies, project approval no.: CIISFTGB2013.

References

[1]. Chinanews. (2017, June 12). BRICS and Developing Countries Civil Society Organizations Forum: People-to-People Connectivity Strengthens the Foundation for Cooperation. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https: //www.chinanews.com.cn/m/gn/2017/06-12/8248228.shtml

[2]. Brazilian Institute of Applied Economics (IPEA). (2021, February 23). Mapa das Organizações da Sociedade Civil. Retrieved from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/

[3]. Fan, L. (2019). Civil society organizations and state governance in Brazil [In Social Organizations Blue Book: China Social Organizations Report (2019)] (pp. 302–320). Beijing, China: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[4]. Brazilian Government. (2021). CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DE 1988 [EB/OL]. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https: //www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm

[5]. Brazilian Government. (2021). Marco Regulatório das Organizações da Sociedade Civil–M-ROSC [EB/OL]. Retrieved April 5, 2021, from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/post/83/entenda-o-mrosc-marco-regulatorio-das-organizacoes-da-sociedade-civil

[6]. Lopez, F. G. (2018). Perfil das organizações da sociedade civil no Brasil. Brasília: IPEA.

[7]. Coston, J. M. (1998). A model and typology of government-NGO relationships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 27(3), 358-382.

[8]. Young, D. R. (2000). Alternative models of government-nonprofit sector relations: Theoretical and international perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149-172.

[9]. Najam, A. (2000). The four C’s of third sector-government relations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 10(4), 375-396.

[10]. Institute for Applied Economic Research. (2024, May 17). Brasil possui mais de 879 mil organizações da sociedade civil ativas [EB/OL]. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.ipea.gov.br/portal/categorias/45-todas-as-noticias/noticias/15065-brasil-tem-mais-de-879-mil-organizacoes-da-sociedade-civil-ativas

[11]. Escudero, C., Galvão, R., & Teixeira, B. S. (2021). Mapa das Organizações da Sociedade Civil: Policy Brief - Em Questão - Evidências para políticas públicas [R/OL]. IPEA, 6(6). https: //www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/em_questao/210721_pb6_divulcacao_v4.pdf

[12]. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. (2022). Censo Demográfico. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html

[13]. Institute for Applied Economic Research. (2022). Analise: Infografico reune dados com o p-erfil das OSCs, Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/post/153/analise-infografico-reune-dados-com-o-perfil-das-oscs

[14]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2024). BRICS countries. Re-trieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gjhdqzz_681964/jzgj_682158/jbqk_682160/

[15]. Ghub (Beijing Green Research Center for Public Welfare Development). (2017). Meeting observation: BRICS New Development Bank and civil society organizations hold a consultation meeting. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //www.ghub.org/

[16]. BRICS Research Team of the Department of International Law and Comparative Law, University of São Paulo. (2021). Discurso inaugural no Fórum Civil do BRICS de 2021 (BRICS Civil Forum 2021) pelo Sr. Sanjay Bhattacharyya, Secretário (CPV & OIA) e BRICS Sherpa. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //sites.usp.br/gebrics/discurso-inaugural-no-forum-civil-do-brics-de-2021-brics-civil-forum-2021-pelo-sr-sanjay-bhattacharyya-secretario-cpv-oia-e-brics-sherpa/

[17]. Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS). (2021). BRICS Civil Forum 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //ris.org.in/bricscivil/index.html

[18]. China Daily. (2022). BRICS civil society organizations hold online seminar on “Public health cooperation and solidarity against the pandemic”. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //hb.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202204/23/WS6263de66a3101c3ee7ad2043.html

[19]. Xinhua News Agency. (2022). BRICS Political Parties, Think Tanks, and Civil Society Organizations Forum Issues Joint Initiative. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from http: //www.news.cn/2022-05/20/c_1128670663.htm

[20]. Agência Senado. (2017). Há 80 anos, União Nacional dos Estudantes faz história no país. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https: //www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/especiais/arquivo-s/ha-80-anos-uniao-nacional-dos-estudantes-faz-historia-no-pais

[21]. Carneiro, D. G. (2018). Estado, organizações da sociedade civil e a política de assistência social: Um olhar sobre o acolhimento institucional para idosos [Master’s thesis, Universidade de Brasília].

[22]. Brazil Special Secretariat for Social Development. (2019, November 22). O que é - A Assistência Social é uma política pública; um direito de todo cidadão que dela necessitar [EB/OL]. Retrieved from https: //www.gov.br/mds/pt-br/acoes-e-programas/suas/servicos-e-programas/o-que-e

[23]. Brazilian Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger, National Secretariat of Social Assistance. (2004). Política Nacional de Assistência Social - PNAS/2004 Norma Operacional Básica - NOB/SUAS [EB/OL]. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https: //www.mds.gov.br/webarquivos/publicacao/assistencia_social/Normativas/PNAS2004.pdf

[24]. Xinhua News Agency. (2015, July 11). Full text: VII BRICS Summit Ufa Declaration. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/world/2015-07/11/c_1115889581.htm

[25]. Xinhua News Agency. (2019, October 25). China-Brazil Football Exchange Center established to promote cooperation in multiple fields. Sina Sports (reprint). Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https: //sports.sina.cn/china/other/2019-10-25/detail-iicezzrr4834892.d.html?from=wap

[26]. Xinhua News Agency. (2021, July 7). São Paulo State of Brazil and Chongqing Municipality hold online seminar on co-building smart cities. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2021-07/07/c_1127630967.htm

[27]. People's Daily Online – International Channel. (2021, October 22). Mianyang, China and Niterói, Brazil sign memorandum of friendly cooperation. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //world.people.com.cn/n1/2021/1022/c1002-32261223.html

[28]. Xinhua News Agency. (2020, August 23). Overseas Chinese as a bridge: Brazil China Chamber of Commerce actively promotes China–Brazil exchanges and cooperation. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/world/2020-08/23/c_1126402378.htm

[29]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2024, October 23). Xi Jinping attends the 16th BRICS Summit and makes an important statement. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https: //www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202410/t20241025_11516006.html

Cite this article

Liu,M.;Zou,S. (2025). A study on the role and positioning of Brazilian civil society organizations under the BRICS mechanism. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(5),22-31.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Chinanews. (2017, June 12). BRICS and Developing Countries Civil Society Organizations Forum: People-to-People Connectivity Strengthens the Foundation for Cooperation. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https: //www.chinanews.com.cn/m/gn/2017/06-12/8248228.shtml

[2]. Brazilian Institute of Applied Economics (IPEA). (2021, February 23). Mapa das Organizações da Sociedade Civil. Retrieved from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/

[3]. Fan, L. (2019). Civil society organizations and state governance in Brazil [In Social Organizations Blue Book: China Social Organizations Report (2019)] (pp. 302–320). Beijing, China: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[4]. Brazilian Government. (2021). CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DE 1988 [EB/OL]. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https: //www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm

[5]. Brazilian Government. (2021). Marco Regulatório das Organizações da Sociedade Civil–M-ROSC [EB/OL]. Retrieved April 5, 2021, from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/post/83/entenda-o-mrosc-marco-regulatorio-das-organizacoes-da-sociedade-civil

[6]. Lopez, F. G. (2018). Perfil das organizações da sociedade civil no Brasil. Brasília: IPEA.

[7]. Coston, J. M. (1998). A model and typology of government-NGO relationships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 27(3), 358-382.

[8]. Young, D. R. (2000). Alternative models of government-nonprofit sector relations: Theoretical and international perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149-172.

[9]. Najam, A. (2000). The four C’s of third sector-government relations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 10(4), 375-396.

[10]. Institute for Applied Economic Research. (2024, May 17). Brasil possui mais de 879 mil organizações da sociedade civil ativas [EB/OL]. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.ipea.gov.br/portal/categorias/45-todas-as-noticias/noticias/15065-brasil-tem-mais-de-879-mil-organizacoes-da-sociedade-civil-ativas

[11]. Escudero, C., Galvão, R., & Teixeira, B. S. (2021). Mapa das Organizações da Sociedade Civil: Policy Brief - Em Questão - Evidências para políticas públicas [R/OL]. IPEA, 6(6). https: //www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/em_questao/210721_pb6_divulcacao_v4.pdf

[12]. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. (2022). Censo Demográfico. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html

[13]. Institute for Applied Economic Research. (2022). Analise: Infografico reune dados com o p-erfil das OSCs, Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https: //mapaosc.ipea.gov.br/post/153/analise-infografico-reune-dados-com-o-perfil-das-oscs

[14]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2024). BRICS countries. Re-trieved October 7, 2024, from https: //www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gjhdqzz_681964/jzgj_682158/jbqk_682160/

[15]. Ghub (Beijing Green Research Center for Public Welfare Development). (2017). Meeting observation: BRICS New Development Bank and civil society organizations hold a consultation meeting. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //www.ghub.org/

[16]. BRICS Research Team of the Department of International Law and Comparative Law, University of São Paulo. (2021). Discurso inaugural no Fórum Civil do BRICS de 2021 (BRICS Civil Forum 2021) pelo Sr. Sanjay Bhattacharyya, Secretário (CPV & OIA) e BRICS Sherpa. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //sites.usp.br/gebrics/discurso-inaugural-no-forum-civil-do-brics-de-2021-brics-civil-forum-2021-pelo-sr-sanjay-bhattacharyya-secretario-cpv-oia-e-brics-sherpa/

[17]. Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS). (2021). BRICS Civil Forum 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //ris.org.in/bricscivil/index.html

[18]. China Daily. (2022). BRICS civil society organizations hold online seminar on “Public health cooperation and solidarity against the pandemic”. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https: //hb.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202204/23/WS6263de66a3101c3ee7ad2043.html

[19]. Xinhua News Agency. (2022). BRICS Political Parties, Think Tanks, and Civil Society Organizations Forum Issues Joint Initiative. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from http: //www.news.cn/2022-05/20/c_1128670663.htm

[20]. Agência Senado. (2017). Há 80 anos, União Nacional dos Estudantes faz história no país. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https: //www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/especiais/arquivo-s/ha-80-anos-uniao-nacional-dos-estudantes-faz-historia-no-pais

[21]. Carneiro, D. G. (2018). Estado, organizações da sociedade civil e a política de assistência social: Um olhar sobre o acolhimento institucional para idosos [Master’s thesis, Universidade de Brasília].

[22]. Brazil Special Secretariat for Social Development. (2019, November 22). O que é - A Assistência Social é uma política pública; um direito de todo cidadão que dela necessitar [EB/OL]. Retrieved from https: //www.gov.br/mds/pt-br/acoes-e-programas/suas/servicos-e-programas/o-que-e

[23]. Brazilian Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger, National Secretariat of Social Assistance. (2004). Política Nacional de Assistência Social - PNAS/2004 Norma Operacional Básica - NOB/SUAS [EB/OL]. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https: //www.mds.gov.br/webarquivos/publicacao/assistencia_social/Normativas/PNAS2004.pdf

[24]. Xinhua News Agency. (2015, July 11). Full text: VII BRICS Summit Ufa Declaration. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/world/2015-07/11/c_1115889581.htm

[25]. Xinhua News Agency. (2019, October 25). China-Brazil Football Exchange Center established to promote cooperation in multiple fields. Sina Sports (reprint). Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https: //sports.sina.cn/china/other/2019-10-25/detail-iicezzrr4834892.d.html?from=wap

[26]. Xinhua News Agency. (2021, July 7). São Paulo State of Brazil and Chongqing Municipality hold online seminar on co-building smart cities. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2021-07/07/c_1127630967.htm

[27]. People's Daily Online – International Channel. (2021, October 22). Mianyang, China and Niterói, Brazil sign memorandum of friendly cooperation. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //world.people.com.cn/n1/2021/1022/c1002-32261223.html

[28]. Xinhua News Agency. (2020, August 23). Overseas Chinese as a bridge: Brazil China Chamber of Commerce actively promotes China–Brazil exchanges and cooperation. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from http: //www.xinhuanet.com/world/2020-08/23/c_1126402378.htm

[29]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2024, October 23). Xi Jinping attends the 16th BRICS Summit and makes an important statement. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https: //www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202410/t20241025_11516006.html