1. Introduction

On a humid morning in Lhasa's Barkhor street, a Tibetan pilgrim prostrates herself on the paved street surrounded by trekking gear shops, souvenir shops, and bubble tea cafes. Her forehead wore a thick layer of callus, a mark of years of devotion. Meanwhile, tourists step around her to photograph the “authentic” moment. Ten meters away, a vendor waves mass-produced prayer flags alongside The North Face knockoffs, and the scent of juniper incense mingles with diesel fumes from the street. Here, in this crowded intersection of the sacred and the commercial, an ancient rhythm of worship persists through the surrounding marketplace.

This scene, not uncommon across Buddhist Asia, is an epitome of transformation, reshaping religious life in the twenty-first century. Shrines and churches increasingly share their courtyards with ticket kiosks, cafés, and social media backdrops; rituals are scheduled around charter‑bus timetables; and spiritual well‑being is bundled into wellness packages alongside aromatherapy and artisanal tea. Religion, once celebrated as an antidote to consumerism's restless desire, now appears deeply entwined with it.

Within this broader transformation, Buddhism presents a particularly compelling—and puzzling—case. Canonical Buddhist teachings valorize non‑attachment (anālaṅkāra), emptiness (śūnyatā), and the transcendence of craving. The Buddha's first sermon at Sarnath identified desire itself as the root of suffering, and monastic codes across traditions emphasize material simplicity. Precisely because its doctrine critiques acquisitive desire, the rapid commercialization of Buddhist space across East Asia poses an analytic contradiction: How can a religion that teaches detachment thrive through souvenirs, tickets, and tourist branding?

Yet the phenomenon is more complex than a simple “materialism corrupts spiritual cultivation” story. Across traditions and continents, sacred spaces have long hosted material demands for the immaterial promises of religion. In Buddhist history, the idea of merit (puṇya) has functioned as a spiritual currency, accumulated through acts of donations to temples, offerings of incense, and sponsorship of rituals. These exchanges were not framed as commercial transactions but as moral acts that accrued metaphysical benefits across lifetimes. What has changed is not the presence of exchange within sacred space, but its scale, visibility, and underlying logic.

Drawing on 12 months of multi‑site fieldwork in Kathmandu, Lhasa, Shanghai, Kyoto, and Tokyo, this essay probes into the paradox by comparing Buddhist sacred spaces in three different countries with distinct histories, cultures, and stages of consumerism: Nepal, China, and Japan. The essay tries to answer two questions: (1) how consumerist logic transforms the production of religious space in East Asian Buddhist contexts, and (2) how this transformation in turn shapes the identities and experiences of the people who use, inhabit, or pass through these spaces.

By integrating Lefebvre's production‑of‑space paradigm with theories of consumer society and state‑religion relations, this study argues that facing the consumerist transformation of religions, religious institutions in the three countries adopt three models: Nepal's community-embedded spaces, China's scenic-hybrid model, and Japan's seamless lifestyle branding. These models represent different spatial strategies that religious institutions design and transform to balance the pressures of market logic and local characteristics while preserving institutional continuity and spiritual legitimacy.

The paper first examines literature on spatial theory, consumer studies, and religion under capitalism to establish the overall theoretical framework. Second, the author traces the history of religions' evolution from traditional merit economies to contemporary spiritual commerce. Then, a methodology section introduces the ethnographic approach across field sites. The result section presents detailed case studies of Nepal, China, and Japan's Buddhist religious spaces, analyzing each space's model. At last, the conclusion synthesizes findings to argue that these spatial strategies represent Buddhism's different adaptation strategies to modern consumerism.

The study is important for three reasons. First, by focusing on East Asian Buddhism, a tradition deeply rooted in material austerity, ritual regularity, and anti-attachment doctrines, this research reveals the tension between religious values and market rationalities. Second, while the commodification of religion has been widely noted in neoliberal societies, a spatially grounded analysis that focuses on the physical, symbolic, and experiential transformation of religious sites is still lacking. Third, as temple spaces increasingly function as hybrid domains, they offer a unique lens to study broader questions about how modern religions will evolve in a consumer-driven world.

2. Literature review

The transformation of Buddhist sacred spaces under consumer capitalism touches three major scholarly conversations: theories of spatial production, critiques of consumer society, and analyses of religion's adaptation to market forces. Rather than operating as separate domains, these literatures converge around a central insight: that space, consumption, and spirituality are co-constituted through social practices that both reproduce and resist dominant economic logics. This convergence becomes particularly visible in Buddhist contexts, where the tension between doctrinal anti-materialism and institutional survival generates novel spatial configurations that existing theories only partially explain.

2.1. Space, power, and the sacred

Henri Lefebvre's theory of the production of space provides the foundational framework for understanding how religious sites are transformed under capitalism. In La production de l'espace, Lefebvre argues that space is not a passive container but a social product generated through the dynamic interaction of three dimensions: spatial practices (perceived space—the material uses and movements through space), representations of space (conceived space—the planned, mapped, and ideologically coded space of planners and authorities), and representational spaces (lived space—the symbolic, experiential domain where meaning is embodied and contested) [1]. Religious spaces, Lefebvre suggests, historically functioned as representational spaces par excellence—sites where cosmic order was made tangible through ritual, architecture, and community gathering.

However, under capitalist spatial logic, Lefebvre argues that abstract space—homogeneous, quantifiable, and oriented toward exchange—increasingly colonizes these lived domains. Christian Schmid, extending Lefebvre's analysis in Henri Lefebvre's Theory of the Production of Space, demonstrates how spatial production intersects with power, governance, and everyday life. During this process, spatial production becomes a means of accumulation that interacts with entire social relations. Schmid's analysis of how global capital and politics reshape local spatial practices is highly relevant to the Buddhist context, where state sponsorship, heritage branding, and transnational tourism converge to produce new spatial assemblages.

Yet Lefebvre's framework, while powerful, was developed primarily through analysis of European urban contexts and requires adaptation for religious spaces operating under different political economies. Edward Soja, in Thirdspace, offers one such adaptation, proposing that spatial analysis must be viewed as a “thirdspace,” a hybrid reality that blends physical, mental, and social dimensions. Soja's concept of “third space” resonates with Nepalese temple complexes where ritual acts, tourist circulation, and emotional experience merge, proving especially useful for analyzing Buddhist sites.

Scholars have gradually realized how religious-sacred spaces can (re)produce social and cultural discourses [2-4]. Massey especially emphasizes space as fundamentally relational and political. Massey argues that spaces are constituted through networks of social relations that extend across scales—from the intimate to the global. Her insight that “places” emerge from the intersection of multiple trajectories illuminates how Buddhist temples become nodes where local devotional practices intersect with transnational tourism circuits, state heritage policies, and global spiritual marketplaces. This relational understanding helps explain why the same doctrinal tradition produces such different spatial configurations across Nepal, China, and Japan. This analysis also helps explain how different groups claim and reconfigure sacred spaces, providing a framework for understanding how Buddhist temples deal with both pilgrims seeking merit and tourists seeking experience.

2.2. Consumer culture and the commodification of experience

The spatial transformation of Buddhist temples cannot be understood without the broader evolution of consumer culture that has redefined the relationship between identity, meaning, and material practice. Baudrillard, in his The Consumer Society, provides insights into how consumption in late capitalism shifts from use-value to sign-value—the symbolic meanings that commodities communicate about lifestyle, status, and identity [5]. Baudrillard's analysis of how objects become “signs to be consumed” rather than tools to be used echoes the transformation of religious artifacts—prayer wheels, incense, meditation cushions—into lifestyle accessories that signal spiritual sophistication or cultural openness. This symbolic dimension of consumption becomes particularly complex in religious contexts, where the boundary between authentic spiritual practice and performative cultural consumption often blurs [5].

Pierre Bourdieu's analysis of “cultural capital” in Distinction helps explain this complexity by showing how cultural practices—including religious ones—function as forms of symbolic capital that mark social distinction. Bourdieu's concept of “habitus” as embodied dispositions that generate and organize practices proves especially relevant for understanding how temple visitors navigate between devotional sincerity and cultural consumption, often within the same spatial encounter.

Rather than simple individual gratification and acquisition, scholars also find other aspects of consumerism. Colin Campbell analyzes the imaginative and emotional aspects of consumer desire. Daniel Miller shows how consumption practices can express care, devotion, and social connection. Bauman further dissects modern consumerism’s roots in contemporary anxieties. Bauman argues that in conditions of social and economic uncertainty, consumption offers temporary relief from existential anxiety—a “liquid” form of meaning-making that substitutes flexibility for commitment and experience for community [6]. His insights are particularly relevant considering how Buddhist temples position themselves as therapeutic spaces offering “mindfulness,” “wellness,” and “authentic experience” to consumers seeking respite from modern life's pressures.

Recent scholarship has begun to examine how these consumer cultures reshape religious practice and space. Vincent Miller's Consuming Religion demonstrates how religious symbols and practices become fragmented and commodified within consumer culture, losing their connection to coherent traditions and communities. Miller argues that this “commodification of the sacred” transforms religion from a way of life into a set of lifestyle options, available for selective appropriation rather than comprehensive commitment. Heelas and Woodhead suggest a more complex picture, arguing that contemporary spirituality represents not simply the commodification of traditional religion but the emergence of new forms of “subjective life spirituality” that blend ancient practices with modern therapeutic and consumer sensibilities [7].

Nevertheless, these classic theories of consumer culture, although analytically powerful, mostly focus on Western contexts and may not fully capture the dynamics of spiritual consumption in Asian societies where economic, political, and cultural logics of exchange, reciprocity, and religions are different. As Gellner points out, the comparison between religious systems in different cultures is a critical question in the anthropology and sociology of Buddhism and Hinduism [8]. Therefore, we also need to look into how these different social contexts can shape the interaction between consumer culture and religious practices.

2.3. Religious adaptation and social contexts

How might differences in state-religion relations, economic development patterns, and cultural backgrounds shape religious institutions?

Koesel's Religion and Authoritarianism offers us a glimpse of how religious organizations in China and Russia develop fundamentally different strategies from their counterparts in liberal democracies, trading political compliance for operational autonomy and economic opportunity [9]. Koesel shows that authoritarian contexts create what she terms “cooperative co-optation,” where religious institutions gain access to resources and legitimacy by aligning with state development goals, including heritage tourism and cultural soft power projection. Similarly, Ashiwa and Wank portray the mutual constitution between religion and state, examining how “the modern category of ‘religion’ is enacted and implemented in specific locales and contexts by a variety of actors” [10].

Borchert also observes Buddhist leadership's complicated relationship with local authority [11]. Monks receive mandatory schooling to learn the core values required by the state. Temples become sites for “patriotic education” alongside spiritual practice, inspiring us on the complex spatial choreography required to satisfy simultaneously religious, political, and commercial demands in authoritarian contexts.

The Japanese context, as well as those of many other liberal democracies, not only presents a different form of religion and politics but also suggests a strong influence of the social, political, and economic contexts on religious agendas. Nelson analyzes Japanese Buddhist temples’ responses to social concerns. Monks and lay practitioners alike take actions to innovate, repose, and reboot existing paradigms to respond to environmental, political, and economic issues [12].

The relationship between economic development and religious commodification is more complex than simple modernization theories suggest. Berger's The Sacred Canopy provides nuanced insights into how economic modernization creates new forms of religious competition [13]. Berger argues that market economies produce “religious pluralism” where spiritual institutions must compete for adherents, leading to increased attention to consumer preferences and service delivery.

All these literatures show that religious institutions' engagement with consumer culture cannot be understood through a universal narrative but must be analyzed within specific contexts of political authority, economic development, and cultural meaning. Different strategies adopted by religious institutions in different countries reflect not simply various stages of modernization but qualitatively different institutional responses to varying political, economic, and cultural contexts.

However, these studies focus on institutional strategy and political adaptation but seldom explore how these dynamics reshape the concrete spatial practices in which religious life exists. Understanding these differences is crucial for analyzing how Buddhist sacred space is produced through the intersection of global consumer culture with local religions. This is what this study attempts to achieve.

This research addresses the gaps in literature by bringing together spatial theory, consumer analysis, and religious studies to examine how Buddhist sacred spaces are produced through the intersection of devotional practice, commercial activity, and state regulation. By comparing temples across different political economies: Nepal's community-embedded spaces, China's state-managed spiritual commerce, and Japan's lifestyle-branded temple tourism—the analysis demonstrates that although Buddhism traditionally teaches detachment and critiques material desire, Buddhist sacred spaces across East Asia have adapted to consumerist pressures in ways that reflect their local economic, political, and historical contexts.

2.4. Religious consumerism in history

The intertwining of religion and economic exchange is far from a modern anomaly. Across the world’s major religious traditions, whether the Catholic sale of indulgences, Islamic zakat and waqf systems, or Hindu temple patronage, economic exchange has long been entangled with spiritual aspiration. These interactions often operate on a moral economy, where donations are exchanged not for immediate material return but for metaphysical benefits, ethical merit, or communal prestige. Buddhism is no exception.

Although Buddhist believers often practice asceticism and Buddhism is known for its no-self (anatta) doctrine, which makes materialism meaningless from the very beginning, the religion is not immune to economic exchange in its later development. In Buddhist history, the idea of merit (punya) has long functioned as a spiritual currency, one that could be accumulated through acts of generosity. Punya involves various types of donations, from donations to temple constructions to offerings of incense, food, or cloth to monastics. These exchanges were not framed as commercial transactions but as moral acts that accrued metaphysical benefits across lifetimes. Yet embedded in these devotional acts was a transactional logic: the expectation of karmic return, whether in the form of blessings, protection, or favorable rebirth. This merit economy persisted for centuries, providing religious institutions with material support while endowing donors with ethical prestige and ritual reassurance.

In premodern contexts, religious spaces often served as both spiritual centers and economic hubs. Temples controlled land, labor, and sometimes entire trade routes. Pilgrimage economies arose around these sacred sites, where relics were venerated, and donations flowed in from both local villagers and itinerant traders [14]. In Theravāda contexts across South Asia and Mahāyāna centers in China and Japan, rituals such as sponsoring sutra recitations or building stupas were promoted as acts of immense merit, often publicized through temple edicts or engraved stone inscriptions [15, 16]. The development of these exchanges laid the groundwork for later transformations, in which sacred value could be expressed through material accumulation, patronage, and public piety.

In modern society, with the arrival of capitalism and urban consumer culture, these embedded economies underwent a significant reformation. Commodities began to enter temple grounds not only as ritual implements but as purchasable souvenirs, dietary products, health remedies, and symbols of identity.

In twentieth-century Japan, for instance, Buddhist temples struggling with financial decline began operating funeral services and gift shops, a shift that only accelerated in the postwar economic boom. In China, especially after the 1980s economic reform, temples were gradually reopened and allowed to engage in revenue-generating activities, ranging from ticketed entry to the sale of amulets, incense packages, and spiritual consultations. Similarly, Nepal's temples and monasteries, despite operating in a largely informal economy, increasingly tailored their spatial practices toward the tourist gaze, incorporating performance, photography zones, and multilingual signage into their rituals.

These shifts, while often critiqued as signs of secularization or religious decline, can be better understood through spatial theory. The spatial logic of the sacred becomes entangled with that of capital: altars are rearranged for photo accessibility, donation counters are placed strategically near entry points, and formerly silent zones are animated by recorded chants and guided tours. Baudrillard's theory of sign-value further clarifies this shift: religious artifacts are not consumed for their use in ritual alone, but for the identities they allow visitors to project: mindful, enlightened, or culturally aware [5]. Sacred space becomes an aesthetic experience, a lifestyle product, a node in the affective economy of modern life.

Yet this essay doesn't try to claim that consumerist saturation has erased the spiritual. Rather, the author attempts to show that it produces new hybrid forms: rituals performed with smartphones in hand, temple visits filtered through Instagram aesthetics, and moments of quiet devotion nested within scripted commercial flows. Rather than trace a unidirectional decline from sacred to secular, this historical trajectory suggests a layered continuity. Ancient logics of merit, patronage, and embodied ritual persist under new guises, folded into the circuits of consumer capitalism not as opposites but as recursive energies. The sacred, in this view, survives not despite commodification but through it, rearticulated at each historical juncture in response to the desires and anxieties of its era.

3. Methodology

This study employs a small-N qualitative comparative case analysis to examine how different political, economic, and cultural contexts shape Buddhist temples' spatial strategies for engaging with consumer culture. The paper analyzes temple cases that represent varying levels of state oversight, economic development, and religious market conditions while controlling: Nepal's Swayambhunath and Thamel district as examples of community-embedded sacred spaces with minimal state regulation, Shanghai's Longhua Temple as a case of state-managed religious commercialization and high-level state oversight, and Japan's hotel-temples as instances of market-driven spiritual commodification with moderate level state regulation.

This paper analyzed both primary ethnographic data and secondary materials, including temple administrative documents, municipal tourism reports, and religious policy directives. Primary data collection involved multi-sited fieldwork conducted between July 2024 and January 2025, including participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and spatial mapping. Secondary sources included scholarly studies of religious commercialization in these regions, media reports on temple tourism, and government heritage designation documents. This comparative approach allows for an in-depth examination of causal mechanisms linking political-economic context to spatial transformation strategies.

The study takes the degree of state regulation and market development as key independent variables. Specifically, whether temples operate under authoritarian oversight (urban China), democratic weak-state conditions (Nepal), or mature capitalist markets (Japan) determines the institutional possibilities and constraints for religious commercialization. The sampling was selected to capture maximum variation in responses to consumerism across different political economies while maintaining religious and spatial comparability.

In Nepal, Swayambhunath represents a historic pilgrimage center deeply embedded in daily ritual practice, while the Thamel district provides an urban context where small-scale sacred sites coexist with tourist infrastructure. These sites offer insight into religious spaces that remain community-integrated despite commercial pressures. In urban China, Longhua Temple exemplifies state-sanctioned religious commercialization, blending market visibility with political compliance requirements. In Japan, hotel-temples like Chishakuin and urban temples like Chion-in represent advanced spiritual commodification, where sacredness is repackaged as a lifestyle experience. Though culturally and institutionally diverse, these sites share key structural similarities: all are Buddhist, all serve both local and tourist populations, and all operate in urban settings with commercial activity.

The dependent variable is the temple spatial strategy for engaging consumer culture, consisting of three dimensions analyzed through Lefebvre's triadic framework. The first dimension is conceived space—how temple authorities and planners organize commercial and ritual zones, measured through spatial layout, signage placement, visitor flow management, and commercial infrastructure integration. The second dimension is perceived space—how visitors navigate and experience these environments, assessed through observation of movement patterns, consumer behavior, and ritual participation. The third dimension is lived space—how meaningful spiritual experience persists or transforms within commercialized settings, evaluated through interview data on authenticity, devotion, and spiritual efficacy.

A total of 52 interviews were conducted. Participants included monks, administrators, lay volunteers, temple visitors, shopkeepers, and local officials. Data collection utilizes multiple methods: fieldnotes from participant observation, audio-recorded interviews, spatial sketches, and photography. Spatial markers documented included location and signage of donation boxes, incense stalls, commercial signage, altars, and designated photography zones. Observation was both naturalistic (participating in rituals and events) and structured (documenting visitor flows, consumer touchpoints, and ritual sequences).

Fieldwork was conducted over multiple visits to each site, typically lasting 3-6 hours per session, with notes recorded on-site and expanded immediately afterward. In Nepal, fieldwork focused on public participation and community ritual behavior. In China, the author obtained permissions for informal staff interviews, with particular attention to state-sanctioned commercial practices. In Japan, observations and interviews focused on how aesthetic and commercial services integrate with spiritual offerings in hotel-temple settings.

4. Results & analysis

4.1. Nepal: community-embedded sacred space

Nepal's Buddhist sacred spaces operate within a distinctive context that shapes their relationship to consumer culture in fundamental ways. As a developing economy with limited state capacity for religious regulation, Nepal maintains what political scientists term a “weak state” context where religious institutions function largely through traditional community networks rather than formal market structures. The country's religious landscape is further complicated by the fluid syncretism between Buddhism and Hinduism, particularly among the Newar population, creating sacred spaces that serve multiple religious communities simultaneously. This political and cultural context produces what this study terms community-embedded sacred space—where spiritual economy, ethnic ritual, and neighborhood ecology form a self-reinforcing structure that subordinates commercial logic to local devotional patterns.

Unlike the carefully staged consumer landscapes of urban China or the lifestyle branding of Japanese hotel-temples, Nepali temples function as living extensions of community life rather than destinations for religious tourism. This difference reflects both economic necessity (most temple donors are local residents rather than paying tourists) and cultural continuity, where sacred sites remain integrated into daily neighborhood rhythms rather than set apart as special consumption experiences.

4.2. Thamel district: spatial integration and vernacular commerce

Kathmandu's Thamel district offers a living demonstration of what Lefebvre calls lived space: the unplanned, continuously practiced layer where everyday life and symbolic meaning overlap. Along its winding lanes, trekking-gear stalls share walls with votive niches; a stupa barely wider than a doorway interrupts traffic at an intersection; and a blackened relief of Mahākāla peers from the façade of a guesthouse. These micro-shrines are not set apart from commerce—they pulse at its centre, forming a vernacular commerce in which buying tea, bargaining over a pashmina, and spinning a small prayer wheel belong to the same rhythm of daily exchange.

In Lefebvre's terms, the conceived space of Thamel—zoned by planners as a tourist district—stands in tension with a perceived space dense with sensory cues of devotion (incense curls from windowsills, butter-lamp flicker glints off shopfront brass), while the lived space is continually reproduced by residents who treat deities as neighbors rather than museum pieces. One Newar shopkeeper explained, “The gods are like family landlords—we share the street. If I sweep the doorway, I sweep the little shrine too.” (Interview, July 2024) This comment reveals how commercial activity and religious maintenance merge into unified daily practice rather than competing for space or attention.

4.3. Padmasambhava: traditional merit economy and informal exchange

A forty-minute ride south from Thamel, the Padmasambhava retreat cave near Pharping reveals another facet of Nepal's community-embedded logic. Reached by stone steps cut into pine-covered slopes, the cave is tended by a lineage of Hindu caretakers who have watched over it for thirteen generations. The site demonstrates how Nepal's weak regulatory context enables informal religious economies that would be impossible under stronger state oversight.

Visitors, including Tibetan pilgrims, Nepali Buddhists, Hindu devotees, and backpackers, may commission a personalized incense offering inside the grotto for a suggested donation of 2,000 Nepali rupees (approximately $ 15). The caretaker interviewed dismissed any suggestion of syncretic tension: “Padmasambhava blesses everyone. For us Hindus, he is a rishi; for Buddhists, he is a Buddha.” (Interview, July 2024) The service operates commercially yet remains embedded within a devotional atmosphere; the fee funds lamp oil, repairs, and the caretaker's livelihood through traditional patron-client relationships rather than formal business structures.

Here, Lefebvre's representations of space, i.e., the ritual instructions, the pricing sign at the cave mouth, frame but do not dominate the practice. Pilgrims continue to circumambulate, chant mantras, and press foreheads to the soot-dark wall according to traditional patterns. Consumption follows devotion rather than preceding it, and economic exchange retains face-to-face intimacy absent from larger heritage sites. This reflects Nepal's cultural context, where religious merit-making continues to operate through traditional reciprocity networks rather than anonymous market transactions.

This community-embedded strategy differs markedly from the scenic-hybrid temples of Shanghai or the lifestyle-branded hotel temples of Kyoto, differences that reflect Nepal's distinctive political and economic context. Shanghai funnels visitors through incense kiosks before prayer; Kyoto packages chanting as a curated wellness experience. Thamel's shrines, by contrast, impose no spatial checkpoint: incense is bought at corner stalls for half the temple price, and offerings are self-directed according to individual devotional preferences.

Even at the Pharping cave, commercial mediation retains traditional characteristics—personal relationship with hereditary caretakers, flexible pricing based on visitor capacity, and integration of payment with ritual instruction—that reflect Nepal's limited integration into formal tourism industries. Economic exchange remains modest, diffused, and subordinate to local ritual ecology, producing sacred spaces that accommodate commerce without being restructured by it.

Thus, Nepal occupies neither an untouched “pre-modern” pole nor a transitional stage toward full commodification. Rather, it exemplifies an alternative pathway shaped by weak state capacity and strong community networks: sacred space sustained by porous integration into neighborhood life, where economic activity supports rather than scripts devotion. In Lefebvre's theoretical terms, abstract space, namely the homogenizing logic of capital, never fully subsumes the lived in Nepal's case, producing hybrid configurations that preserve community control while enabling modest commercial adaptation.

4.4. China: scenic-hybrid sacred space

In China, Buddhist spaces such as Shanghai's Longhua Temple and Jing'an Temple exemplify a middle stage of spatial commodification: religious sites embedded in market infrastructure and political visibility. This hybrid character is not a transitional “middle stage” in a linear developmental arc, but a spatial strategy shaped by China's specific blend of rapid urbanization, managed religious tolerance, and socialist market economy.

Operating within China's “socialist market economy,” where rapid economic development occurs under continued Communist Party control, religious institutions. Like Koesel notes, engage in “cooperative co-optation,” where religious institutions gain operational autonomy by aligning with state development priorities. Urban temples like Longhua and Jing'an function within municipal tourism strategies, heritage preservation programs, and cultural soft power projection, creating institutional incentives for commercial development that would be impossible under different political systems.

This state-managed commercial context produces distinctive spatial characteristics. Henri Lefebvre's theory of spatial production helps clarify the spatial strategies of urban Chinese temples. Lefebvre argues that space is not inert or neutral but socially produced through a triad: conceived space (planned by architects and authorities), perceived space (used and navigated by people), and lived space (imbued with symbolic meaning and affective experience).

In Shanghai's Buddhist temples, the conceived space is engineered by temple managers and municipal planners alike: carefully landscaped courtyards, controlled visitor flows, and ritual zones separated from commercial zones reflect both religious design and regulatory compliance. For example, the Jing'an Temple is reconstructed atop a metro station and flanked by luxury malls. The temple even incorporates escalator-accessible prayer halls and velvet-roped photo zones that frame the gilded Buddha statues as the city’s landmarks as much as spiritual icons.

The perceived space, in turn, is choreographed to accommodate both ritual and tourism: incense burners are cordoned off for crowd control, guided donation paths direct foot traffic through relic halls and gift shops, and signage alternates between doctrinal quotes and public safety messages. Visitors, including both domestic pilgrims and international tourists, move through these spaces not just as worshippers or consumers, but as regulated subjects of a state-monitored religious economy.

What makes this configuration “hybrid” is precisely its institutional double coding. Unlike Nepal, where religious institutions are embedded within local community rhythms, Chinese Buddhist temples are embedded in dual logics: they are devotional centers and public cultural showcases, subject to both market incentives and political oversight. Longhua Temple, for instance, hosts large-scale merit rituals and state-sponsored commemorative events, while also operating a thriving religious gift economy through its “Dharma Items Pavilion,” where temple-branded incense, amulets, and seasonal zodiac charms are sold in glass cases resembling luxury boutiques.

This spatial hybridization reflects broader ideological considerations. On the one hand, Lefebvre's lived space, the domain of affect and memory, is not erased. Pilgrims continue to kneel, chant, and light incense with sincerity, even in front of surveillance cameras and automated donation machines. On the other hand, that sincerity is now inseparable from managed experience—regulated timings, aestheticized sacredness, and monetized access. The temple becomes a zone where ritual affect, urban spectacle, and state legibility converge.

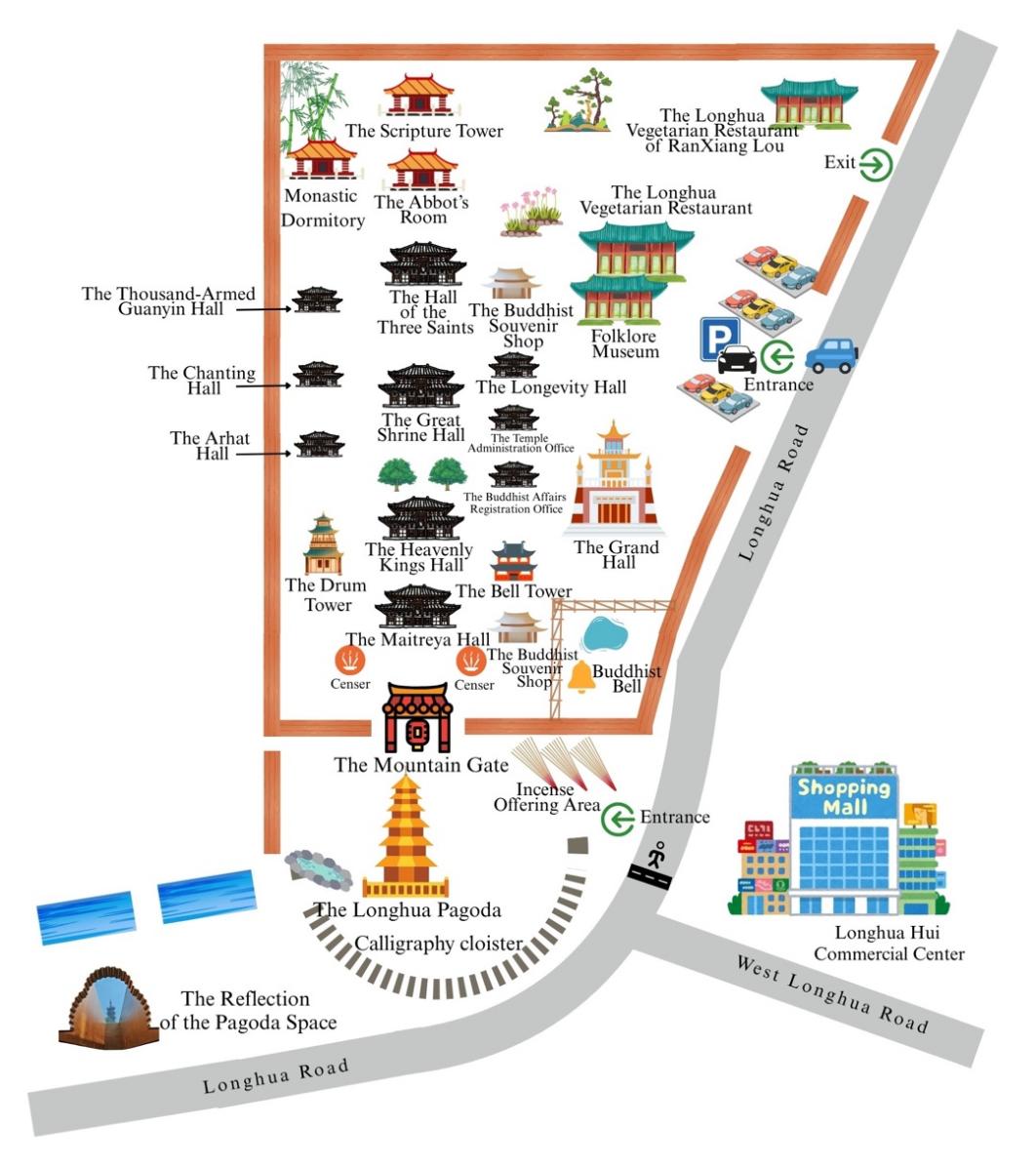

4.5. Longhua Temple: choreographed consumption and ritual flow

Longhua Temple offers a striking example of such managed spatial choreography (see Figure 1). Upon entry, visitors are funneled through a systematic sequence: a long arcade of donation counters, merit lanterns, and incense bundles precedes access to the main prayer halls. Incense burners are cordoned off for crowd control, guided donation paths direct foot traffic through relic halls and gift shops, and multilingual signage alternates between doctrinal quotes and public safety messages. Visitors move through these spaces not just as worshippers or consumers, but as regulated subjects of a state-monitored religious economy.

This spatial arrangement reflects what Lefebvre describes as the interplay between conceived space (planned by authorities) and perceived space (experienced by users), where visitor behavior is structured through architectural design rather than explicit regulation. Visitors are first encouraged to purchase merit items, then guided into ritual zones for incense burning and prayer, and finally spill into open courtyards ideal for photography. This spatial choreography frames the visitor's experience as a ritualized consumer journey: sacred intention flows seamlessly into aesthetic consumption, with prayer folded into a rhythm of offerings, documentation, and exit.

The incense altar strategically located before the Maitreya Hall ensures that burning incense functions as both a devotional gesture and spatial transition, producing aromatic clouds that enhance the aesthetic atmosphere while guiding visitors through predetermined ritual sequences. This choreography blurs Lefebvre's categories of representational space (the lived, symbolic domain of practice) and representations of space (the official, planned layout). Embeds affective intensity within commercial and spatial scripts, making sincerity, control, and spending mutually reinforcing rather than contradictory.

4.6. Incense and commodified sincerity

Among the various practices shaped by commodified temple design, incense burning stands out as one of the cases that demonstrate how religious experience and consumer activity are interwoven.

In urban Chinese temples like Longhua and Jing'an, incense burning has evolved into a practice of layered meaning: part ritual, part performance, part economic transaction. While Lefebvre's framework helps illuminate how space is produced through the triad of conceived, perceived, and lived dimensions, it is in the intersection of these levels, especially within the act of burning incense, that the consumerist restructuring of sacred space becomes visible.

At Longhua Temple, just outside the temple's formal threshold, incense vendors sit by the metro exit, selling the same three-stick bundles for 10 yuan (about 1.3 USD), about half the official price inside. Still, many visitors bypass these offerings, choosing instead to purchase incense within the temple property at a fixed price of 20 yuan. This choice reflects more than preference; it signals a belief in the ritual legitimacy conferred by institutional space. Incense bought within the boundary of the temple, although materially identical, carries symbolic weight: it is not merely incense; it is sanctioned incense.

The phenomenon of “burning high incense” (shao gaoxiang), which means paying substantial sums for premium ritual participation, and temple' other thriving religious gift economy, such as temple-branded incense, amulets, and seasonal zodiac charms sold in glass cases resembling luxury boutiques, illustrate how traditional merit-making adapts to contemporary consumer culture. Temples like Yonghegong in Beijing or Guangxiao Temple in Guangzhou advertise premium incense tiers, often with priority access or symbolic rewards. Jing'an Temple offers limited-edition peach-blossom charms during Valentine's season and green jade pendants specifically marketed for business success.

An interview with Ms. Liu, a 48-year-old entrepreneur visiting from Hangzhou, reveals the spiritual wish embedded in religious commodities: “I paid 888 yuan (about 124 USD) for the tall incense in front of the main hall. My son is applying for university this year—I want to do everything possible. It is not just money—it is sincerity. If others see you burn the best incense, they know your heart is in it.” (Interview, December 2024). Mr. Zhang, a 33-year-old e-commerce executive from Shanghai, also admitted the complex mix of consumerist attraction and spiritual sincerity, “I don't believe in everything, but I buy the amulet every year. One for me, one for my daughter. It's tradition, and it looks good. Some of my clients even ask where I got mine.” (Interview, December 2024)

This response illustrates a crucial logic: commodified sincerity. Drawing on Baudrillard's idea of sign value , the incense becomes not only an offering to the divine but also a public statement of piety and social class [5]. High incense use reflects “the symbolic transformation of religious devotion into consumer performance,”a trend further intensified by temple marketing that presents incense sets as fortune-enhancing packages.

Moreover, the psychological mechanism behind this behavior mirrors Bauman's Liquid Modernity: in an age of uncertainty, consumers seek quick symbolic resolution. Incense becomes insurance against bad luck, disease, and academic failure. And as Lefebvre might suggest, the lived space—the internal experience of the worshipper—is not eliminated by commodification but rather reorganized [6]. Devotion persists, but it now expresses itself through acts that double as consumption.

Spatially, Longhua's incense areas are flanked by donation boxes and digital QR codes for “karma transfers”—a seamless integration of spiritual and financial flows. The fact that these are placed along the one-way path through the temple reveals a logic of flow management akin to Lefebvre's abstract space: worshippers are guided not just spiritually but behaviorally, in alignment with commercial interests.

4.7. Spiritual privilege and symbolic capital

Beyond the standard 20-yuan incense ritual, a shadow economy of high incense and large-scale donations has emerged within urban Chinese temples. While incense in this context already represents a commodified ritual object, high incense extends this logic into a socially stratified system of privilege and symbolic capital. Worshippers who burn specially designated high incense or who contribute substantial financial donations often receive access to exclusive services and spaces not available to the general public.

This informal system is not advertised but widely understood through social circulation and temple familiarity. As Mr. Yang, a 54-year-old doctor and regular visitor to Longhua Temple, explained, “It’s not really about how much you burn, but if you donate regularly, the temple knows. They will greet you by name. During festival times like the Lunar New Year or the Ghost Festival, we sometimes receive little gifts, like phone charms, amulets, even stickers, they say have been blessed by the abbot. I have also been invited to drink tea at the rear teahouse. It is a quiet place, only open to familiar faces. They serve temple-made cakes and hot water steeped with mountain herbs. Once, when my mother was seriously ill, a monk even came to our home to chant for her. It gave her peace. That’s not something money buys directly—it’s about building a relationship over time.” (Interview, January 2025)

The practices Mr. Yang describes operate within Lefebvre's concept of lived space, where affective relations and informal gestures override formal architecture. The private blessings, edible offerings, and personal outreach emerge as symbolic reciprocations within a moral economy shaped by both Confucian reciprocity and consumerist expectation. The conceived space of the temple may remain open and egalitarian in theory, but in practice, its perceived and lived modalities become stratified through these gift cycles.

These benefits form what might be described as devotional entitlements: privileges gained not through doctrinal knowledge but through sustained financial offerings. They mirror the logics of contemporary luxury loyalty programs, where repeat customers are rewarded with exclusivity cloaked in intimacy.

More importantly, these benefits reconfigure religious merit as something that can be accumulated materially. While Buddhist doctrine traditionally frames merit as the fruit of intention and karma, this system allows it to be partly purchased through visible acts of generosity. The result is a dual axis of sacred participation: one navigated by tourists and casual worshippers through standard offerings, and another by elite donors through personalized devotional economies.

This bifurcation complicates any simple reading of temple space as either sacred or commodified. Rather, as Lefebvre might argue, it is a space of negotiated practice, where the abstraction of religious egalitarianism is overlaid by the lived hierarchies of capital and recognition.

4.8. Japan: lifestyle-branded sacred space

Contemporary Japan, which operates within a mature capitalist democracy with relatively moderate state regulation of religion, faces severe challenges from demographic decline, urbanization, and weakening traditional family ties that historically sustained temple economies. Unlike contexts where state support or community obligation provides institutional security, Japanese temples must compete in open markets for both members and revenue, creating powerful incentives for innovation and service diversification.

As a result, Japanese Buddhist institutions have developed what this study terms seamless lifestyle-branded sacred space to strategically rebrand themselves through aesthetic appeal, therapeutic services, and cultural programming. **Unlike the communal embeddedness seen in Nepal, where temples remain enmeshed in local social life, or the scenic-hybrid model in urban China, where ritual and consumerist flows coexist in visible yet often compartmentalized spatial configurations, the Japanese hotel temples (shukubō) that transform Buddhist temples into hybrid spaces of lodging, leisure, and spiritual service represents a distinctive mode of adaptation to consumerism: one in which commerce is camouflaged as culture, and spiritual tourism is naturalized into the rhythms of everyday leisure.

4.9. Hotel temples and immersive spiritual experience

The hotel temple phenomenon exemplifies Japan's seamless integration strategy. Field research at a Kyoto hotel temple revealed how traditional monastic infrastructure is adapted for contemporary consumers' needs. When asked about the motivations behind offering overnight stays to tourists, the manager-monk of a Kyoto hotel-temple explained: “We wanted people to experience the atmosphere of the temple not as outsiders, but as participants—even if they don't understand Buddhism. A night's stay is a kind of gentle entry point.” (interview, August 2024) The facilities, indeed, are intentionally designed to reflect this ethos. Guests sleep in tatami-matted rooms lined with wooden screens that echo traditional monastic quarters yet equipped with modern amenities and curated lighting to enhance aesthetic appeal. Here, the temple is not simply a spiritual infrastructure but an immersive spatial experience.

Using Lefebvre's spatial triad, the transformation becomes clear: the conceived space blends Zen minimalism with luxury hospitality through careful architectural planning; the perceived space is choreographed through sequential affective cues, such as incense, calligraphy, garden views, that create atmosphere for spiritual consumption, while the lived space enables genuine contemplative experience within commercial frameworks.

4.10. Staged authenticity and performative spirituality

The morning ritual at hotel temples illustrates the complex relationship between authenticity and performance in commercialized sacred space. According to a monk, “We don't alter the core ritual for guests, but we've timed and designed it so that anyone, even a tourist, can join before breakfast.”(interview, August 2024) However, in reality, approximately 80% of foreign visitors attend the 6:00 AM meditation and chanting session, despite many not identifying as Buddhist, while participation among Japanese guests remains significantly lower. All morning session participants are paying guests—no one is from the local community, and even a few monks join the session. This demographic pattern reflects the exotic appeal of ritual experience for international travelers seeking "authentic" cultural encounters.

The ceremony itself has rich symbolic signals but is at the same time unmistakably theatrical. Monk's process into the hall with solemn chants, rhythmically wave a vajra in synchrony, and feed goma fire sticks into a ritual fire during sutra recitation. Monks process with solemn chants, rhythmically manipulate ritual implements, and feed goma fire sticks into ceremonial flames during sutra recitation. Periodic incense offerings punctuate the chanting, filling the space with an aromatic atmosphere under soft dawn lighting.

Yet several interviewees described the experience as feeling more like a cultural “show” than a purely religious rite. One participant from the Netherlands remarked, “It was beautiful, but almost too polished—like a performance.” (interview, August 2024) The precise choreography and no restrictions on photography after the recitation render the sacred into consumable spectacle.

This performance-like quality of the morning chanting ritual in Japanese hotel temples embodies what Dean MacCannell concept of “staged authenticity”: cultural performances that appear intimate and spontaneous but are designed for tourist consumption [17]. Originally proposed in the context of tourism, MacCannell suggests that as tourists search for the “real” behind-the-scenes culture (“backstage”), tourism operators craft carefully curated versions of that very backstage—decorated authenticity that appears intimate but is itself performative*.

In the context of the hotel temple, the early morning Goma fire ritual functions precisely in this way: it presents itself as a raw, sacred practice, yet is choreographed with the aesthetic and emotional cadence of a cultural show. Monks chant in unison, strike ritual implements in timed rhythm, and feed firewood into the ceremonial flames. These are all gestures in the Goma fire ritual that evoke genuine devotion but also offer aesthetic spectacle. The scene is carefully tuned: smoke curling upward, amber lighting filtered through shōji screens, and ample opportunities for discreet photography once the sutras end. These elements together produce what interviewee Ms. Yu called “a beautifully packaged silence.” (interview, August 2024) For some, the experience is spiritually meaningful; for others, it is a curated pause in their consumer itinerary. Either way, the boundary between reverence and receptacle collapses.

This performative authenticity is further masked by the temple's projection of daily life. Guests are invited to share simple vegetarian meals, sit in common spaces designed to resemble monastic quarters. As Yu described, “The monks know who the loyal guests are.” (interview, August 2024)

In doing so, hotel temples invert the usual direction of commodification: they render consumer acts invisible by wrapping them in the signs of community, care, and continuity. The sacred is not abandoned—it is domesticated. What is sold is not just a room or ritual, but an illusion of return to the everyday sacred. This blurring of commerce and communion exemplifies a key feature of contemporary Japanese temple spaces: they do not fight consumerism head-on but assimilate it so thoroughly that it becomes indistinguishable from the spiritual itself.

5. Conclusion

Drawing from Lefebvre's spatial theory, the research focuses on how sacred space is (re)produced in the interactions of special design (conceived space), spatial experience (perceived space), and individual practices or rituals (lived space). The study demonstrates that Buddhist sacred spaces in Nepal, China, and Japan exhibit distinctive spatial strategies in response to consumerism, shaped by their unique sociopolitical, economic, and cultural environments. Nepal's community-based religious spaces reflect deep historical embeddedness; urban China's temples are entangled with market and state infrastructures; and Japanese hotel temples have rearticulated religion as a lifestyle product. These models are not merely different stages on a linear trajectory of modernization, but qualitatively distinct strategies that reflect how religious institutions adapt to the pressures of market logic.

At the same time, limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The sample of interviewees remains small and skewed towards accessible temple visitors and monks amenable to being recorded. Observations and interviews were constrained to some high-security zones (e.g., Jokhang interior) and were time-limited in Japan. Moreover, the focus on Buddhist spaces excludes other religious traditions that may adopt different spatial logics under commodification. Future research could expand into Christian or Islamic sites facing similar consumer pressures or apply GIS mapping techniques to track spatial flow more precisely.

In a nutshell, this study affirms that religious space is not passively commodified but actively reimagined. Through Lefebvre's lens, the sacred emerges not as a fixed category but as a produced space: contested, curated, and contingent upon broader societal forces. The three spatial strategies analyzed here are not endpoints but adaptive logics in an ongoing negotiation between faith and finance. Far from erasing religiosity, commodification reorganizes it—sometimes into spectacle, sometimes into service, and occasionally, into shared community life.

References

[1]. Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.).Blackwell.(Original work published 1974)

[2]. Kong, L. (2002). In search of permanent homes: Singapore’s house churches and the politics of space.Urban Studies, 39(9), 1573–1586. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00420980220151761

[3]. Martin, A. K., & Kryst, S. (1998). Encountering Mary: Ritualization and place contagion in postmodernity. InH. J. Nast & S. Pile (Eds.),Places through the body(pp. 207–230). Routledge.

[4]. Holloway, J. (2006). Enchanted spaces: The séance, affect, and geographies of religion.Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(1), 182–187. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00507.x

[5]. Baudrillard, J. (1998). The consumer society: Myths and structures (C. Turner, Trans.).SAGE Publications.(Original work published 1970)

[6]. Bauman, Z. (2007). Consuming life. Polity Press.

[7]. Heelas, P. (2008). Spiritualities of life: New age romanticism and consumptive capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

[8]. Gellner, D. N. (2023). The spaces of religion: a view from South Asia.Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 29(3), 553-572.

[9]. Koesel, K. J. (2014). Religion and authoritarianism: Cooperation, conflict, and the consequences. Cambridge University Press.

[10]. Ashiwa, Y., & Wank, D. L. (Eds.). (2020). Making religion, making the state: The politics of religion in modern China. Stanford University Press.

[11]. Borchert, T. A. (2017). Educating monks: Minority Buddhism on China’s southwest border. University of Hawaii Press.

[12]. Nelson, J. K. (2013). Experimental Buddhism: Innovation and activism in contemporary Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

[13]. Berger, P. L. (2014). The many altars of modernity: Toward a paradigm for religion in a pluralist age. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

[14]. Aruljothi, C., & Ramaswamy, S. (2019). Pilgrimage tourism: Socio-economic analysis. MJP Publisher.

[15]. Kieschnick, J. (2003). The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture. Princeton University Press.

[16]. Gombrich, R. (1988). Theravāda Buddhism: A social history from ancient Benares to modern Colombo. Routledge.

[17]. Ning, W. (2017). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. InThe political nature of cultural heritage and tourism(pp. 469-490). Routledge.

Cite this article

Xu,Z. (2025). The production of commodified sacred space: a comparative study of Buddhist temples and consumer culture in Nepal, China, and Japan. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(7),26-36.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.).Blackwell.(Original work published 1974)

[2]. Kong, L. (2002). In search of permanent homes: Singapore’s house churches and the politics of space.Urban Studies, 39(9), 1573–1586. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00420980220151761

[3]. Martin, A. K., & Kryst, S. (1998). Encountering Mary: Ritualization and place contagion in postmodernity. InH. J. Nast & S. Pile (Eds.),Places through the body(pp. 207–230). Routledge.

[4]. Holloway, J. (2006). Enchanted spaces: The séance, affect, and geographies of religion.Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(1), 182–187. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00507.x

[5]. Baudrillard, J. (1998). The consumer society: Myths and structures (C. Turner, Trans.).SAGE Publications.(Original work published 1970)

[6]. Bauman, Z. (2007). Consuming life. Polity Press.

[7]. Heelas, P. (2008). Spiritualities of life: New age romanticism and consumptive capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

[8]. Gellner, D. N. (2023). The spaces of religion: a view from South Asia.Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 29(3), 553-572.

[9]. Koesel, K. J. (2014). Religion and authoritarianism: Cooperation, conflict, and the consequences. Cambridge University Press.

[10]. Ashiwa, Y., & Wank, D. L. (Eds.). (2020). Making religion, making the state: The politics of religion in modern China. Stanford University Press.

[11]. Borchert, T. A. (2017). Educating monks: Minority Buddhism on China’s southwest border. University of Hawaii Press.

[12]. Nelson, J. K. (2013). Experimental Buddhism: Innovation and activism in contemporary Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

[13]. Berger, P. L. (2014). The many altars of modernity: Toward a paradigm for religion in a pluralist age. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

[14]. Aruljothi, C., & Ramaswamy, S. (2019). Pilgrimage tourism: Socio-economic analysis. MJP Publisher.

[15]. Kieschnick, J. (2003). The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture. Princeton University Press.

[16]. Gombrich, R. (1988). Theravāda Buddhism: A social history from ancient Benares to modern Colombo. Routledge.

[17]. Ning, W. (2017). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. InThe political nature of cultural heritage and tourism(pp. 469-490). Routledge.