1. Introduction

The concept of “physical literacy” was mentioned more than eighty years ago. The term “physical literacy” first appeared in an article published in a U.S. journal called Health and Education in 1938. At that time, public schools in the United States had already become aware of the need to cultivate students’ physical literacy as well as psychological literacy. Nearly sixty years later, in 1993, British scholar Margaret Whitehead introduced and articulated the concept again. The idea of physical literacy has become well known and accepted in many Western countries and has been applied in practice. At the same time, physical literacy has gained recognition from international organizations: international sports science bodies and educational councils have concurred that the purpose of physical education is to cultivate physical literacy, with physical literacy seen as its outcome. UNESCO incorporated “physical literacy” into the new International Charter on Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sport, and regards the education of physical literacy as one important aim and task of physical education. Beyond the United States and the United Kingdom, more countries have joined the exploration of physical literacy theory and practice—countries such as Canada, Australia, and Singapore have attached particular importance to physical literacy, elevating it to the national level and even using it as a basis for school physical education policy. China has also stepped up work on physical literacy education, highlighting the issue at the level of national strategy: the national Outline for Building a Strong Sports Nation explicitly proposes developing young people’s physical literacy. After the Outline was promulgated, professors, scholars, and teachers in this field in China poured into the tide of research. Physical literacy is a form of lifelong education; it is inclusive education; it is an education that transcends—the means of self-transcendence. Physical literacy education is a matter of concern for individuals, families, society, and the state. In view of this, the present paper reviews and examines the concept of physical literacy and its three philosophical foundations.

2. Understanding the concept of physical literacy

2.1. The concept of physical literacy

Physical literacy refers—relative to an individual’s endowments—to the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding that enable one to maintain bodily vitality throughout the life course [1]. Physical literacy recognizes the intrinsic value of physical activity; it overcomes the tendency to regard physical activity merely as a means to other ends; across all forms of physical activity, it provides a clear objective; it affirms the necessity and value of physical activity in the school curriculum; it rejects the view that physical activity is merely an optional form of recreation; it emphasizes that physical activity is important for all people, not only those who are most capable in the field; it articulates the rationale for lifelong participation in physical activity; and it clearly describes the importance of our physical dimension from cradle to grave.

2.2. The connotations of physical literacy

Physical literacy is a universal concept applicable to everyone—regardless of time and place, age, innate endowment, level of physical competence, or the cultural environment in which one lives. In every culture, whether in meeting the demands of daily life or in organized physical activities, there exist both opportunities and challenges. As human beings, we exist in the world in embodied form; the specific world in which each individual lives will foster the development of his or her embodied capabilities. Everyone can develop and improve their physical literacy and benefit from the growth of this capacity. The connotations of physical literacy can be understood from the following perspectives: ① The potential for physical literacy exists in all people. Physical literacy depends on an individual’s endowment across all capabilities, especially motor skills, and is closely related to the cultural environment in which the person lives. ② A physically literate person acts with composure, effectiveness, and confidence when faced with diverse physical challenges. Such a person can better manage bodily dimensions, perceive the surrounding physical environment, and—on the basis of physical capacities, particularly coordination and control—interact smoothly with the demands of daily life and physical activity, responding effectively to both familiar and novel requirements. ③A physically literate individual possesses a more developed self-awareness. This awareness facilitates genuine interaction with the surrounding environment, fosters self-esteem and self-confidence, and generates positive personal growth. ④ Nonverbal communication as self-expression. Effective self-expression arises from sensitivity to and awareness of one’s embodied capabilities. Such communication cultivates empathy, enables deeper perception of others’ inner worlds, and fosters meaningful interpersonal interaction. Physically literate individuals are confident in their embodied abilities, interact with their environment and others in ways that generate positive self-feedback—such as self-respect, resilience, confidence, and pride. This sensitivity and assured self-awareness, together with accumulated experience, support effective nonverbal self-expression and a greater capacity to respond to interpersonal interactions. ⑤ The ability to evaluate one’s own physical performance. Physically literate individuals are acutely aware of their bodily dimensions and the experiences gained from participating in physical activity. This embodied awareness—i.e., bodily consciousness—enables them to describe and evaluate their movements, discuss how to improve them, and assess the relationship between exercise and lifestyle, including the degree to which exercise shapes one’s way of life. By drawing on experiences gained through bodily engagement in physical activity, they can appreciate and understand its positive impact on overall health and well-being.

2.3. The interrelationship among the attributes of physical literacy

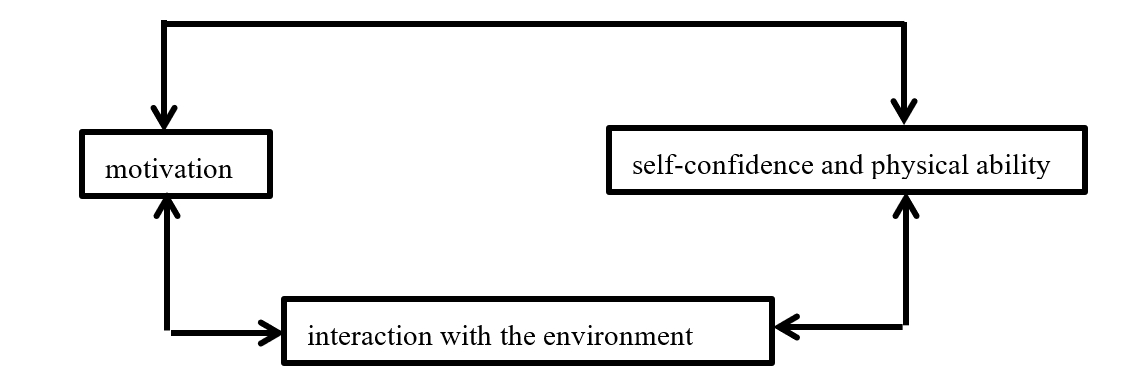

The attributes of physical literacy can be described in two stages. At its core lie motivation, confidence and physical competence, and interaction with the environment. These three attributes influence and reinforce one another.

Motivation encourages participation, which in turn strengthens confidence and physical competence. The development of confidence and competence, in turn, sustains or enhances motivation. Confidence and competence promote interaction with the environment. Interaction with the environment, and the new challenges it entails, further enhance confidence and competence. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship among motivation, confidence and physical competence, and interaction with the environment.

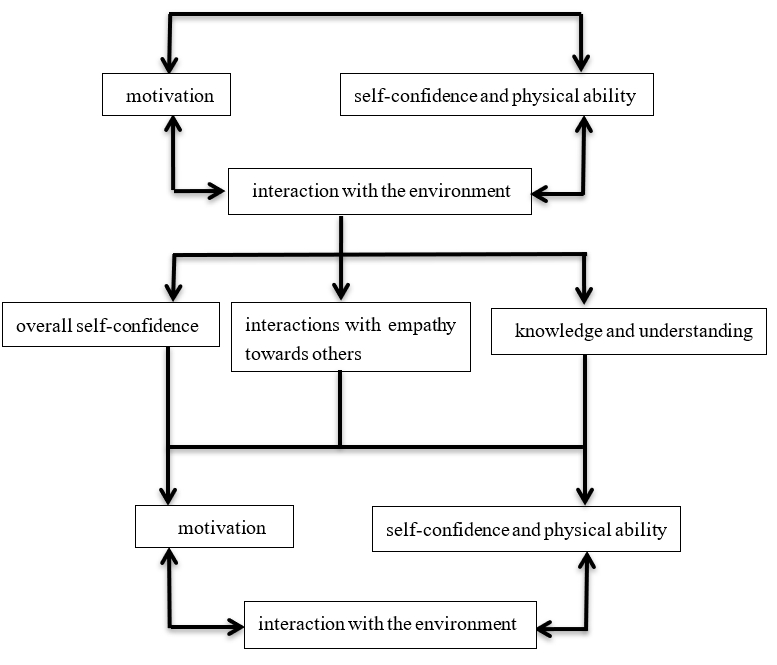

In addition, three other attributes—global self-confidence, empathetic interaction with others, and knowledge and understanding—develop significantly as motivation, confidence, physical competence, and environmental interaction grow. For example, when individuals gain positive experiences through physical activity, they develop heightened self-awareness and global self-confidence. Awareness of embodiment and healthy self-esteem promote fluent self-expression, perceptiveness, and empathetic engagement with others. Knowledge and understanding are enriched and advanced through broad participation.

These three attributes in turn help further develop the core attributes—motivation, confidence and competence, and interaction with the environment. For instance, confident self-awareness can transform into motivation and a willingness to accept challenges; fluent interaction with others can build confidence and the ability to collaborate in physical activity settings; and knowledge and understanding can support the development of physical competence and sensitivity to diverse environments. Figure 2 illustrates the relationships among the various attributes of physical literacy.

3. The “mind–body monism” of physical literacy

Monism stands in contrast to dualism. The origins of dualism can be traced back to Plato, whose philosophy was largely built upon the idea that the intellect is superior while the body is inferior. However, the most influential figure was René Descartes in the seventeenth century, who established two fundamentally distinct human attributes—mind and body—with the mind considered undoubtedly more important. Descartes’ interpretation of this view was based on his own reasoning: the only thing he could not doubt was that he was thinking. Hence, he declared, “I think, therefore I am.” According to Descartes’ epistemological philosophy, the mind is the subject of cognition and can exist independently of the body. Although human beings are a union of mind and body, Descartes insisted that they are distinct rather than unified [2]. From his philosophical position of cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”), Descartes inferred that the essence of the world lies in the soul. The body, originally one with the soul, was reduced to an object of cognition for the soul. In his framework, the mind is a unique force: whether receiving images from the senses together with illusions, applying images stored in memory, or forming new ideas that engage the imagination—sometimes so strongly that imagination alone cannot contain them. He wrote: When this distinctive force of the mind is applied to imagination together with the senses, it is called vision, touch, and so forth. When it is applied to imagination alone in order to retain various images, it is called memory. When the mind acts on imagination to form new impressions, it is called concept or idea. Finally, when it works purely on its own, it is called understanding or comprehension [3]. From Descartes’ perspective, human vision, touch, memory, imagination, and comprehension all arise from the power of the mind and have no connection with the body. The body, in his view, plays no role in these cognitive activities. Descartes sought to explain why we engage in different cognitive activities and what their nature is. Yet what actually requires explanation is the activities themselves, for it is precisely through the body’s involvement that such activities exist at all. Moreover, dualism regarded bodily activities as having little value beyond maintaining survival and prolonging life—a view unacceptable to many who engage in physical activity.

Monism, in contrast, holds that human beings are essentially indivisible wholes. Bresler’s propositions of “the body in the mind” and “the mind in the body” express the interdependence of mind and body. This idea of “body in mind, mind in body” stands in stark opposition to Cartesian dualism. In both ontological and methodological senses, monism has two sides. Ontologically, monism can be divided into materialist monism and idealist monism. Methodologically, it can be divided into concrete monism and abstract monism. The basic standpoint of monism is that we are, at root, a single and indivisible entity, even though composed of different capacities. These capacities are interdependent and closely cooperative. From a monistic perspective, the human being is a highly complex entity containing various capacities that mutually construct and enrich one another. The concept of physical literacy identifies a particular capacity that is deeply and significantly interrelated with all other capacities. Although often treated as a functional attribute when considered in isolation, the reality is that we exist in material form, and our bodily capacities constitute an essential dimension of life. Physical literacy embodies a form of mind–matter monism known as animism of matter—where matter contains spirit and spirit contains matter, the two unified as one.

4. The existentialism of physical literacy

The foundation of existentialist belief is that individuals create themselves through life and interaction with the world. This continuous engagement with the surrounding environment is referred to as intentionality [3]. Through intentionality, individuals are drawn to perceive and respond to everyone and everything around them. We live in a state of constant connection with the world, so our existence manifests as an ongoing dialogue between ourselves and our environment. We are born with great potential, including inherited strengths and dispositions, but how we shape ourselves depends on the experiences we acquire. At its core, the individual is one who “exists in this world.” A central principle of existentialism is that “existence precedes essence.” [4] In other words, our uniqueness or essence emerges through the experiences we accumulate across our entire lives. Who we are at present is the result of the environments we have encountered and the accumulation of those experiences.

The perspective of phenomenologists aligns closely with that of existentialists. Phenomenologists emphasize that each person perceives the world from a unique standpoint, a uniqueness shaped by one’s prior experiences. Every individual is engaged in interpreting the world, and with every perception our understanding of the world changes, thereby shaping how we view the future. Each lived experience and insight transforms the self, making each of us unique.

Although it may be difficult to imagine, phenomenologists argue that nothing “out there” is rigid or fixed; instead, it is through our perception and encounter that meaning arises. The term phenomenon derives from the Greek, referring to that which appears before us, though not necessarily that which is explained by science. A phenomenon represents the fusion of prior experience, because it provides the interpretive context for objects or situations in the environment. Familiar objects or scenarios are infused with previous associations, and our ideas about them are influenced by those associations. An individual’s understanding of the external world is realized through perception, which is itself a product of accumulated past experiences. This process resembles what psychologists describe as assimilation. In assimilation, individuals must alter or interpret what they perceive so that it aligns with existing understandings—allowing us to see things in a way consistent with our prior frameworks. This suggests that, in a certain sense, each person’s world is different and unique to them. For example, if we have previously been stung by a wasp and are allergic, the mere sight of a wasp will trigger fear; by contrast, if we have never had a frightening encounter with wasps, their presence may be seen merely as a stimulus—or carry no consequence at all. Psychologists link assimilation with accommodation. Accommodation refers to the way individuals must modify their existing understandings in order to make sense of new experiences. For instance, if someone we had previously thought incompetent demonstrates meticulous efficiency in completing a task, our evaluation of that person must change. The perceiver interprets the world from their own standpoint, shaping the situation in ways that make sense to them. At the same time, to some extent, the individual must also accommodate what is perceived. In this process of adapting to new experiences, those very experiences reshape the perceiver. Thus, every individual is continuously creating a personal world, and personal growth and development unfold through ongoing interaction with the world.

Phenomenologists use existentialist language to explain why and how we become who we are: it is because the accumulation of our experiences shapes the way we interact with the world. When intentionality drives us to engage with our surroundings, we become ourselves—rather than anyone else—at every moment.

5. The embodied phenomenology of physical literacy

Descartes attempted to reconcile the opposition between the cognitive subject and cognitive object through consciousness. Husserl, however, fell into the trap of idealism by negating the existence of the objective world. Heidegger regarded Dasein’s being-in-the-world as the phenomenon of facticity itself. Facticity refers to each individual’s concrete mode of existence in everyday life. Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of the body holds that the body is no longer merely an entity opposed to thought, but rather a form of being endowed with the capacity to “think.” All our mental activities and cognition are grounded in the body’s integrated sensorimotor capacities and lived bodily experience.

Dasein’s being-in-the-world is essentially cognitive, and cognition itself is a mode of existence. Only by returning to the natural body can Dasein reflect upon its ontological existence and avoid the suspicion of phenomenology as a purely transcendental enterprise. Cognition is not simply a physiological mechanism, nor a purely conscious activity; it is a bodily phenomenon, inherently embodied. The body is the basis of the psyche, and all cognitive activities of the mind arise through the participation of the body. The body is thus a conscious body, a body capable of cognition. While transcendentalism holds that knowledge precedes experience, the transcendental forms of knowledge must be situated within the body and belong to it. Through bodily participation, the self is connected with the world; only by having a body can Dasein truly possess its own horizon of existence. The concept of “physical literacy” inherently contains Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of bodily consciousness, namely, embodied phenomenology. The body is the general medium through which we possess the world [5], the universal tool that mediates the relationship between understanding and the perceived world. It is through bodily experience that we form cognition of objects, thereby constructing the unity of those objects. Consequently, the experiential qualities of the body constitute the appearance of recognized objects and the representation of the world. The body, in maintaining its transcendence before consciousness, prevents the world from dissolving into nothingness. The body’s wonder lies in its dual ability to perceive and to experience, while simultaneously feeding the results of experience back into itself—coming from the body and returning to the body.

Embodiment is manifested through what is called operative intentionality, where perception and response play a decisive role. The embodied dimension of perception stems from our employment of prior experiences related to objects. Our interactions with particular aspects of the environment or the world serve as indispensable bridges for understanding them. When we engage with an object or feature of the world, we experience a primordial bodily sensation, an embodied relation—for instance, the dizziness and fear a person feels when standing at the edge of a cliff. Such original bodily feelings become part of our understanding of those features. Many aspects of the world are perceived from our embodied standpoint. Merleau-Ponty affirmed this, stating that “the perceiving mind is an incarnated mind” [6]. In operative intentionality, movement and perception are closely interwoven; these dimensions of human existence are not separate, but interconnected.

The body is not merely a physical structure but a living, experiential structure. Experience is the body’s own experience, the consciousness of the body itself. This capacity of the body is often overlooked or reduced to mere representation. The body is not simply a physical system; anatomical and physiological knowledge provides only the most basic tools for understanding the body’s internal structures. Within the empiricist view, the body’s active and adaptive role in engaging with the environment is diminished. Yet beyond its physical structure, the body also manifests itself phenomenally through its intact physicality. In this sense, the body is a living body with its own experiential structure. Experience has a personal, embodied character—it is the lived history and record of bodily activity. This is our true body: a body of dual structure, both perceivable and perceiving. Mental activities such as sensation, memory, reasoning, and judgment are all formed through bodily experience and are external expressions of it.

6. Conclusion

The concept of “physical literacy” is both old and new. It is old because the idea of physical literacy was proposed long ago; it is new because in the present era it has been endowed with renewed vitality, has received growing attention from many countries, and has been re-recognized for its importance. Physical literacy extends across the entire human lifespan, from birth to death, and cannot be separated from its cultivation. It holds significant meaning and value for every individual, regardless of natural talent; it is not the exclusive right of athletic elites.

Physical literacy encompasses motivation, confidence, physical competence, interaction with the environment, knowledge, and understanding. These attributes are interconnected, influencing and permeating one another. At its core, physical literacy is the desire to be active, to sustain participation in activities, to explore new forms of movement, and to improve physical fitness. An individual who has developed physical literacy will hold a positive attitude toward participation in physical activity and will take practical steps to engage in such activity on a weekly or even daily basis.

As an expression of fundamental capability, physical literacy serves as a vehicle for individuals to realize and develop their unique humanity. Whenever we exercise any latent ability, we become more fully human. In a sense, such experiences bring intrinsic satisfaction and affirmation. Each experience contributes to becoming a complete person. Every activity helps us become our true selves, builds self-confidence, and physical activity is no exception.

Monism of mind and body, existentialism, and embodied phenomenology together provide the three main philosophical foundations for the concept of physical literacy. Physical literacy acknowledges the philosophical view that mind and body are interdependent and inseparable. The embodied dimension of human existence is a vital human asset: through living our embodied dimension and through interacting with our surrounding environment, we deepen our understanding of the world, enhance self-awareness, and strengthen self-confidence. Everyone has the potential to develop physical literacy, and all individuals can cultivate it within the limits of their endowment. More importantly, each person progresses along their own personal journey and benefits from the growth of physical literacy.

References

[1]. Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy throughout the life course.Taylor & Francis e-Library.

[2]. Mao, D. (2015). On the transition from dualism to monism.Journal of Jilin Institute of Education, 31(5), 129–130.

[3]. He, J. (2017). Existence, for-itself, and choice: Reflections on existence in Sartre’s existentialist philosophy.Journal of Harbin University, 38(6), 5–8.

[4]. Zhang, Y. (2012). The “descending path” toward “reconciliation”: An analysis of Spinoza’s monism and its transformation of Descartes’ mind-body dualism.Journal of Jiangsu Administration Institute, 63(3), 26–31.

[5]. Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception.Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

[6]. Yan, Y. (2016). A study on Merleau-Ponty’s embodied phenomenology.Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Cite this article

Yuan,X.;Li,J. (2025). Philosophical thinking on physical literacy. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(8),8-13.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy throughout the life course.Taylor & Francis e-Library.

[2]. Mao, D. (2015). On the transition from dualism to monism.Journal of Jilin Institute of Education, 31(5), 129–130.

[3]. He, J. (2017). Existence, for-itself, and choice: Reflections on existence in Sartre’s existentialist philosophy.Journal of Harbin University, 38(6), 5–8.

[4]. Zhang, Y. (2012). The “descending path” toward “reconciliation”: An analysis of Spinoza’s monism and its transformation of Descartes’ mind-body dualism.Journal of Jiangsu Administration Institute, 63(3), 26–31.

[5]. Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception.Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

[6]. Yan, Y. (2016). A study on Merleau-Ponty’s embodied phenomenology.Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.