1. Introduction

The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), which systematically identifies mood disorders through observed syndromes, categorises behavioural and emotional problems into internalising, externalising, and mixed disorders [1]. Internalising disorders, which manifest as emotional distress, have become an increasing concern for public health due to their rising prevalence and significant impact on individuals’ daily functioning. In the proposed ASEBA model, internalising disorders are problems characterised by the considerable presence of emotional disturbances or subtle behaviour inhibition, known as internalising symptoms [2], such as somatic complaints [3], avoidance and withdrawal [4], and constant ruminations [5]. In psychopathological studies integrating DSM-5’s identified mood disorders into the ASEBA model, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), multiple phobias (such as social phobias), and more emotional disorders are categorised within the spectrum of internalising disorders [2, 6]. Studies highlight the increasing prevalence rate of different internalising disorders among populations since 1990 to 2021, with a 1.8-fold increase in global MDD, a 52% increase in GAD, and an increase in dysthymic cases [7-9]. The prevalence of internalising syndromes is especially increasing among adolescents [10]. Although the specific cause of the increasing prevalence rate remains unclear, several social factors, such as the development of social media, have been linked to the emergence of internalising symptoms [11, 12]. As a result, treatments for such internalising disorders remain in high demand. According to Karrouri et al.’s holistic review, psychotherapy, with supporting pharmacological interventions, is the prevailing treatment for internalising disorders; specifically, talk therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) are proven effective [13]. However, the heavy reliance on verbal interactions imposes a communication barrier. While such barriers may create little obstacle for most patients, individuals comorbid with communicative deficiency – due to physiological impairment, neurodevelopmental language disorders, or severe impairment in social communicative ability, which is often related to internalising disorders [14] – may experience minimal benefits [15]. Complementing the limitation brought about by talk therapy, modern clinical psychology explores interdisciplinary therapies designed to overcome communication barriers. One successful approach is Visual Art Therapy (VAT) [16], in which therapists utilise visual elements and creative processes – such as painting, sculpting, and ceramics – to facilitate better expressions of thoughts, thereby fostering therapeutic effects [17]. By integrating studies on VAT treating different internalising disorders and a holistic review of the effectiveness of VAT, this review aims to provide evidence for VAT as an alternative therapy beyond conventional talk therapies for patients who may not express their cognitions effectively, thereby ensuring the availability of psychological treatments for minorities.

2. Methodology

This review primarily examines literature from five databases, including PubMed, Elsevier, Google Scholar, Taylor & Francis, and PsycINFO. Boolean search strategies were employed using keywords such as (“art therapy” OR “visual art therapy” OR “art”) AND (“communication” OR “communication deficit” OR “developmental language disorder” OR “internalising disorders” OR “depression” OR “anxiety” OR “trauma”). Research conducted with randomised controlled trials (RCTs), case studies, or systematic reviews was included. No restrictions on publication date or language were applied; as a result, the essay comprises journals published from 1992 to 2025 (see Table. 1). Within the field of art therapy, studies concerning music, literature, performance, and those integrating interdisciplinary approaches (such as music and art therapy) were also excluded if they lacked isolating the efficacy of each artistic approach. Furthermore, within the search term concerning communication deficit comorbidity, studies investigating non-internalising disorders were also excluded.

|

Research Type |

Studies |

Number (n) |

Overall Result |

|

Randomised Control Trial |

[18] |

1 |

The study compares different forms of VAT and indicates their similar effectiveness in alleviating internalising syndromes. |

|

Systematic Review |

[19-21] |

3 |

Research draws on studies across a variety of RCT experiments (12 from [19], 8 from [20], 15 from [21]), indicating that though VAT is effective in treating internalising disorders, researches yield limited statistical significance due to varying clinical practice. |

|

Case study |

[22-26] |

5 |

Research across different regions is drawn, and studies showcase both forms of VAT to be effective in reducing depressive and anxious symptoms. Case studies investigating Art in Therapy reported increasing confidence in communication for patients experiencing communication difficulties. |

3. Visual art therapy approaches

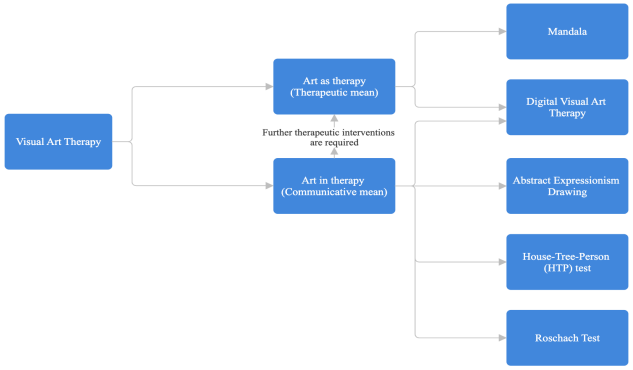

While including overlaps in the specific therapeutic methods of implementation, VAT is primarily implemented through two approaches (Figure 1): one focuses on enhancing communication, enabling therapists to more effectively analyse patients’ cognition and emotions (Art In Therapy, AIT), while the other uses the creative process as therapy, aiming to reduce distress and anxiety (Art As Therapy, AST) [18]. These two approaches can be applied in combination across stages of diagnosis, communication, and therapy. Currently, VAT is often used to target young children with internalising problems or elderly patients with dementia, as these groups primarily experience restrictions in verbal expression [19, 27]. While empirical evidence has showcased the potential ability of VAT in alleviating internalising problems such as depressive and anxious syndromes [18, 19, 28], relevant studies still contain statistical uncertainty regarding its effectiveness on different age groups, especially among adults [29]. The following sections will evaluate VAT according to its two approaches: AIT and AST. Under each aspect, specific forms of creative processes will be further categorised, with their therapeutic efficacy being reviewed.

3.1. Art In Therapy (AIT)

AIT often aids individuals with communication deficits, enabling them to express complex ideas through artistic creations. AIT itself may provide a limited therapeutic effect beyond the communication benefits, as such a method mainly aims to create complex communication, but it can be used in combination with other therapeutic methods, such as CBT, IPT, or AST means approaches. Referencing Roberts’s theory regarding the relationship between emotional communication and styles of artistic creation, specifically Abstract Expressionist paintings, Roberts highlights how mechanical movement in paintstrokes may bypass conscious control, allowing more raw and complex emotions within the unconscious mind to be expressed [30]. This principle may further apply to other forms of artistic creation, such as sculpture or installation, in which patients’ tactile interactions with art mediums may facilitate fewer difficulties in expressing innate and complicated thoughts, hence making AIT plausible to aid communication.

In practice, Lazar et al.provide an example of AIT’s effectiveness through the application of art creation (pottery, drawing, and painting) within psychotherapies for patients with internalising problems (presence of distress and anxious syndromes) and speech impairment (due to cognitive impairment, stroke, or developmental language disorders) comorbidity [22]. By incorporating tactile and visual interactions within collaborative art creation in group therapy, Lazar et. al showcases the potential of visual art in meeting patients’ complex expression needs whilst reducing previous emotional distress caused by the fear of stigmatisation; according to self-reported information, this is potentially due to the less intense power dynamic in VAT between therapists and patients compared to prevailing forms of talk therapies, and patients are more willing to engage in interactions with therapists [22]. Furthermore, in attempts to understand AIT’s ability to alleviate communication withdrawal symptoms in depression, Riley compares therapeutic results between talk therapy and an interdisciplinary approach, cross-pollinating AIT (drawing as a medium) and talk therapy [23]. The case study investigates female adolescents exhibiting withdrawal, depressive, and anxious syndromes. Compared to traditional talk therapy, where participants may disengage from the sessions and refuse to admit a sense of distress, the researcher’s integration of drawing activities in a group setting (drawing makeup on paper) increases participants’ willingness to communicate their concerns, hence facilitating better communication between patients and therapists [23]. The longitudinal study providing different conditional trials reinforces the possibility of engaging participants and facilitating better interactions when individuals are more withdrawn from sessions of therapy. While the case study highlights the potential of AIT in reducing communication withdrawal, it provides limited statistical evidence that quantifies the results of the two trials on the group.

AIT’s artistic communication can also play a significant role in aiding unconventional communication deficiencies, such as helping with the treatment of PTSD. Wild and Gur find that there is a positive association between the emergence of PTSD and impaired verbal memory, meaning that PTSD patients may face communication deficits in verbally recalling their memories [31]. To facilitate expression of traumatic memories, Schouten et al. and Talwar report that trauma-focused VAT circumvents impaired verbal memories and allows better visual externalisation of traumatic experiences [24, 25]. Participants engaging in VAT have also self-reported less distress when communicating traumatic experiences and greater confidence in future communication, both verbally and visually [24]. Thus, the researchers highlight AIT’s effectiveness in helping PTSD patients to express memories that may be difficult to communicate in conventional talk therapy.

In summary, various case studies evidence the communicative benefits that AIT yields and hence indirectly increases therapeutic effect. However, its limitations are also significant, which is shown through the comprehensive therapeutic techniques used in the case studies, as AIT alone may not be used as a therapeutic means and requires adjunctive talk therapy. Moreover, few studies systematically review AIT in aiding withdrawal syndromes in internalising disorders through a quantified method to measure it under RCT [32]. Hence, it is an indicator for future studies to understand the extent of effectiveness for AIT in aiding common speech withdrawal present in internalising disorders in comparison to traditional talk therapy.

3.2. Art As Therapy (AST)

Beyond the application of visual art as a supportive tool in therapy, therapists also recognise the intrinsic therapeutic potential of visual art-making. One example is the use of a mandala, which is a religious form of drawing that employs circular and repeated forms, and the therapeutic use of mandala dates back to Jung, who used VAT to alleviate anxious syndromes [33]. From a theoretical perspective, as the therapeutic approach circumvents verbal expressions, it is a potential form of VAT that can be used for patients experiencing communication deficiency and internalising disorder comorbidity. However, modern meta-analyses, such as Støre & Jakobsson, highlight that the form of manda itself has no significant benefits compared to other free-drawing activities [20]. This provides an insight into the mechanism behind mandala and similar drawing ASTs in alleviating distress, which the repetitive process allows individuals to enter the state of flow, characterised by high attentiveness, thereby reducing anxiety level [34].

To examine AST’s effectiveness related to the interdisciplinary therapy combining AIT and CBT, Hartz & Thick conducted an RCT, splitting clients into either AIT or AST group therapy to examine AST’s ability to increase self-esteem among female juvenile delinquents with low talk therapy response due to mood and communication withdrawal [18]. In the AST condition, researchers adopted art-making processes that mimic repetitive processes (paper collage, yarn basket-making), allowing participants to enter the state of flow. As a result, through a self-report questionnaire, Hartz and Thick found that participants in AST experienced the same level of therapeutic benefit in raising self-esteem and alleviating distressing syndromes compared to those in the AIT condition, hence proving the similar effectiveness of AST as AIT.

While there was no significant difference between the level of increasing self-esteem among the two conditions, the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA, dividing self-esteem into 9 categories) scoring highlights that individuals attending AST showed statistically higher self-perceived social acceptance (1.05 points increase) compared to participants in AIT (0.6 points increase) [18]. This improvement may reflect enhanced confidence in social communication and interactions. Furthermore, new modes of VAT, such as digital-VAT (d-VAT), are also used to resolve withdrawal tendencies in individuals experiencing internalising disorders. Mochimaru & Demaine’s case study analysed d-VAT’s capacity to alleviate loneliness in patients with Hikkikomori, a form of internalising disorder characterised by prolonged social withdrawal and continuous depressed mood [26, 35]. By highlighting the remote nature of artistic creation, d-VAT may increase confidence and reduce social withdrawal. However, the efficacy of d-VAT remains uncertain due to the small sample size and limited studies, highlighting the need for future research. Hence, future statistical studies are required to provide a conclusive implication on the potential effectiveness of d-VAT. Overall, studies indicate that AST has similar effectiveness to AIT when treating individuals with withdrawal tendencies, justifying AST as an alternative therapeutic means for patients if they experience minimal benefit from talk therapy. Compared to AIT, AST relies less on talk therapy, as the main mechanism that relieves internalising syndromes is through the working process; hence, it yields higher potential when treating individuals with moderate to severe withdrawal and communication deficiency symptoms.

4. Comparison between AIT and AST

In summary, both AIT and AST represent valid therapeutic components within the broader spectrum of VAT, with empirical evidence highlighting their effectiveness in treating internalising disorders. While the two approaches share similarities, they also differ in mechanisms, implementation, and target populations, which may cause the form of VAT to suit certain contexts better (refer to Table 2).

|

Art In Therapy |

Art As Therapy |

|

|

Characteristics and Mechanism |

Uses art to aid communication, which allows patients to better express their cognitions, memories, and emotions. It may not function as therapy on its own and requires other talk therapy interventions to alleviate internalising syndromes. |

Uses the practice of art directly as a therapeutic means. Through enthralling patients into the process of art-making, it ensures individuals enter hyper attentiveness and hence reduce internalising syndromes. |

|

Medium requirement |

No restriction on artistic medium, but values more creative work that includes personal voice. |

No restriction on artistic medium, but values a more repetitive working process (colouring, basket-weaving) that heightens focus. |

|

Effectiveness |

Yields a limited therapeutic effect on itself and requires additional psychotherapy in conjunction. No significant therapeutic difference from AST in terms of effectiveness [18]. |

Yields substantial therapeutic effect on itself. No further psychotherapy is required, but it may be implemented in conjunction. No significant therapeutic difference from AIT in terms of effectiveness [18]. |

|

Targeting Age Group |

Often used among adolescents and elderly patients. |

Often used among adolescents and young adults. Sometimes used for post-cancer psychotherapy [36]. |

|

Empirical Evidence |

There is little statistical evidence showcasing the extent of effectiveness of AIT compared to other therapies among participants with internalising disorders and communication deficiency comorbidity, but more case-study evidence highlighting therapeutic effectiveness compared to AST. |

There is little research conducted on AST. Meta-analyses highlight that its therapeutic effectiveness varies among age groups and communities [29]. Further empirical evidence is required to justify the extent of effectiveness. |

5. Discussion

Referencing previous analyses of the different forms of VATs, current clinical studies demonstrate that VAT predominantly utilises the creative process and hands-on experiences to reduce anxious symptoms as well as to facilitate better communication within comprehensive therapy sessions. Though AIT and AST have slightly different focuses within therapy, both approaches are based on the mechanism of increasing sense of control and autonomy, through either self-expression or repetitive process of art-making, to increase communication inclination [18], hence reducing internalising symptoms such as withdrawal and persistent distress. Furthermore, Franklin also highlights that the reduced sense of distress may also be due to art’s ability to allow patients to visualise their cognitive distortions, as a result, emphasising the dispositional quality of traumatic events [37]. Though the exact mechanism of VAT remains ambiguous between different schools of explanation, it has been proven to be relatively effective as an alternative treatment for patients experiencing limited benefits from traditional talk therapies.

With regard to clinical studies examining VAT effectiveness, there is a predominant use of case studies. While such a research design provides a holistic review concerning participants’ well-being before and after VAT, the relatively small sample size, lack of a controlled condition, and mainly regional investigation, reduce the validity of the findings and the level of generalisation among global internalising disorder and communication deficiency comorbid populations. Beyond case studies, meta-analyses investigating the validity of RCT experiments conducted on VAT also yield ambiguous results [19, 21]; though VAT is effective to a great extent, the intervention standardisation among different RCTs is ambiguous and highly variable [19]. As a result, a baseline standardisation for VAT, along with standardised art therapist training, shall be implemented to foster an evidence-based therapeutic technique. In comparison to talk therapy, such as CBT, VAT has an advantage in engaging the participants who are withdrawn from verbal interactions, as seen in Reily’s 2003 case study [23]. This engagement allows therapists to understand patients better and, hence, create unique therapeutic plans. This advantage is also seen in other forms of art therapies, such as music therapy, where individuals’ expression of emotions circumvents verbal communication obstacles [38]. However, due to the lack of standardised practice in both visual and music therapies, therapeutic outcomes may vary across practitioners, potentially reducing consistency compared to CBT.

Current clinical applications of VAT primarily focus on pre-school toddlers, adolescents, and the elderly, as this form of psychotherapy may reduce communication barriers and foster complex expression of thoughts limited by verbal expression. However, the essay advocates for the application of VAT for adults as well as further research conducted on the adult population, since individuals of the adult population may also experience limited expression of emotion due to varying linguistic capabilities. Moreover, current clinical approaches also emphasise offline artistic practices, which may lead to low accessibility; the emergence of d-VAT creates a pioneering example of making VAT more accessible regardless of region. While making global research on VAT more plausible, the essay also believes that future research may further understand such an interdisciplinary approach combining digital technology with VAT and its effectiveness in addressing severe internalising symptoms.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, considering the evidence for VAT’s effectiveness in treating internalising disorders and aiding communication, the essay highlights the special value of such forms of psychotherapy as an alternative treatment. It allows psychotherapy to be more accessible and effective when facing patients experiencing mood disorders and communication difficulties. Within the spectrum of VAT, while AIT and AST both successfully target patients with such comorbidity, and both treatments are similarly effective, AIT functions as an adjunctive treatment, whilst AST can be used to treat more severe cases of communication withdrawal compared to AIT. For future research, large-scale RCTs across diverse age, cultural, and socioeconomic groups are recommended to establish robust statistical evidence concerning VAT’s efficacy. Additionally, preliminary studies in combining VAT with other forms of art therapy, as well as technology (d-VAT), are also worthy of exploration, as they ensure greater clinical accessibility.

References

[1]. Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., & Rescorla, L. A. (2017). Empirically based assessment and taxonomy of psychopathology for ages 1½–90+ years: Developmental, multi-informant, and multicultural findings.Comprehensive Psychiatry, 79, 4–18. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.03.006

[2]. Forns, M., Abad, J., & Kirchner, T. (2011). Internalizing and externalizing problems. In Springer eBooks (pp. 1464–1469). https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_261

[3]. Haftgoli, N., Favrat, B., Verdon, F., Vaucher, P., Bischoff, T., Burnand, B., & Herzig, L. (2010). Patients presenting with somatic complaints in general practice: depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders are frequent and associated with psychosocial stressors.BMC Family Practice, 11(1). https: //doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-67

[4]. Struijs, S. Y., Lamers, F., Vroling, M. S., Roelofs, K., Spinhoven, P., & Penninx, B. W. (2017). Approach and avoidance tendencies in depression and anxiety disorders.Psychiatry Research, 256, 475–481. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.010

[5]. Olatunji, B. O., Naragon-Gainey, K., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B. (2013). Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta‐analysis.Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 20(3), 225–257. https: //doi.org/10.1037/h0101719

[6]. Eaton, N. R., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Carragher, N., & Krueger, R. F. (2015). Transdiagnostic factors of psychopathology and substance use disorders: a review.Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(2), 171–182. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-1001-2

[7]. Chen, X., Li, F., Zuo, H., & Zhu, F. (2025). Trends in Prevalent Cases and Disability‐Adjusted Life‐Years of Depressive Disorders Worldwide: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study from 1990 to 2021.Depression and Anxiety, 42(1). https: //doi.org/10.1155/da/5553491

[8]. Bie, F., Yan, X., Xing, J., Wang, L., Xu, Y., Wang, G., Wang, Q., Guo, J., Qiao, J., & Rao, Z. (2024). Rising global burden of anxiety disorders among adolescents and young adults: trends, risk factors, and the impact of socioeconomic disparities and COVID-19 from 1990 to 2021.Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1489427

[9]. Luo, J., Tang, L., Kong, X., & Li, Y. (2024). Global, regional, and national burdens of depressive disorders in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years from 1990 to 2019: A trend analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 92, 103905. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103905

[10]. Blomqvist, I., Blom, E. H., Hägglöf, B., & Hammarström, A. (2019). Increase of internalized mental health symptoms among adolescents during the last three decades.European Journal of Public Health,29(5), 925–931. https: //doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz028

[11]. Rosenthal, S. R., Buka, S. L., Marshall, B. D., Carey, K. B., & Clark, M. A. (2016). Negative experiences on Facebook and depressive symptoms among young adults.Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 510–516. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.023

[12]. Maras, D., Flament, M. F., Murray, M., Buchholz, A., Henderson, K. A., Obeid, N., & Goldfield, G. S. (2015). Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth.Preventive Medicine,73, 133–138. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.029

[13]. Karrouri, R., Hammani, Z., Benjelloun, R., & Otheman, Y. (2021). Major depressive disorder: Validated treatments and future challenges.World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(31), 9350–9367. https: //doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9350

[14]. Segrin, C. (2000b). Social skills deficits associated with depression.Clinical Psychology Review,20(3), 379–403. https: //doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00104-4

[15]. Hill, E., Tonta, K., Boyes, M., Norbury, C., Griffiths, S., Goh, S., & Ryan, B. (2025). “Why would someone like me with DLD want to sit in a room and talk? How would that make me feel better?!” Developmental Language Disorder and the language demands of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.International Journal of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. 18, 405–424 (2025). https: //doi.org/10.1007/s41811-025-00254-3

[16]. Hu, J., Zhang, J., Hu, L., Yu, H., & Xu, J. (2021). Art therapy: a complementary treatment for mental disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686005

[17]. Haeyen, S., Van Hooren, S., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2015). Perceived effects of art therapy in the treatment of personality disorders, cluster B/C: A qualitative study.The Arts in Psychotherapy, 45, 1–10. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.005

[18]. Hartz, L., & Thick, L. (2005). Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: A comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches.Art Therapy, 22(2), 70–80. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129440

[19]. Zhang, B., Yang, L., Sun, W., Xu, P., Ma, H., & Abdullah, A. B. (2025). The effect of the art therapy interventions to alleviate depression symptoms among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Clinics,80, 100683. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2025.100683

[20]. Støre, S. J., & Jakobsson, N. (2022). The effect of mandala coloring on state anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Art Therapy, 39(4), 173–181. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2021.2003144

[21]. Han, B., Jia, Y., Hu, G., Bai, L., Gains, H., You, S., He, R., Jiao, Y., Huang, K., Cui, L., & Chen, L. (2024b). The effects of visual art therapy on adults with depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta‐analysis.International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 33(5), 1183–1196. https: //doi.org/10.1111/inm.13331

[22]. Lazar, A., Feuston, J. L., Edasis, C., & Piper, A. M. (2018). Making as expression.CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173925

[23]. Riley, S. (2003). Using art therapy to address adolescent depression. InC. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of art therapy, 220-228. Guilford Press.

[24]. Schouten, K. A., Van Hooren, S., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2018). Trauma-focused art therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study.Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(1), 114–130. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712

[25]. Talwar, S. (2006). Accessing traumatic memory through art making: An art therapy trauma protocol (ATTP).The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34(1), 22–35. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.001

[26]. Mochimaru, Y., & Demaine, K. (2022). Digital art therapy and social withdrawal in Japan.Creative Arts in Education and Therapy,8(1), 99–112. https: //doi.org/10.15212/caet/2022/8/16

[27]. Rentz, C. A. (2002). Memories in the Making: Outcome-based evaluation of an art program for individuals with dementing illnesses.American Journal of Alzheimer S Disease & Other Dementias, 17(3), 175–181. https: //doi.org/10.1177/153331750201700310

[28]. Abbing, A., Baars, E. W., De Sonneville, L., Ponstein, A. S., & Swaab, H. (2019). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adult women: a randomized controlled trial.Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–14. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01203

[29]. Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., Van Hooren, S., De Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., & Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials.PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0208716, 1-19. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

[30]. The Psychology of American Abstract Expressionism. (2023).International Journal of Art and Art History, Vol. 11(No. 1), 9–22. https: //doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v11n1p2

[31]. Wild, J., & Gur, R. C. (2008). Verbal memory and treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder.The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(3), 254–255. https: //doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045922

[32]. Mirabella, G. (2015). Is art therapy a reliable tool for rehabilitating people suffering from brain/mental diseases?The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(4), 196–199. https: //doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0374

[33]. Zhang, M., Liu, X., & Huang, Y. (2023b). Does mandala art improve psychological well-being in patients? A systematic review.Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 30(1), 25–36. https: //doi.org/10.1089/jicm.2022.0780

[34]. Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,56(5), 815–822. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

[35]. Kondo, N., Sakai, M., Kuroda, Y., Kiyota, Y., Kitabata, Y., & Kurosawa, M. (2011). General condition of hikikomori (prolonged social withdrawal) in Japan: Psychiatric diagnosis and outcome in mental health welfare centres.International Journal of Social Psychiatry,59(1), 79–86. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0020764011423611

[36]. Dadashi, N., Mojen, L. K., Ilkhani, M., Nasirie, M., Mirzaee, H. R., & Boozaripour, M. (2025). Effect of mandala art therapy on quality of life in breast cancer patients.Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 26(7), 2533–2540. https: //doi.org/10.31557/apjcp.2025.26.7.2533

[37]. Franklin, M. (1992). Art therapy and self-esteem.Art Therapy,9(2), 78–84. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1992.10758941

[38]. Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M., Vanhala, M., & Gold, C. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: randomised controlled trial.The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(2), 132–139. https: //doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085431

Cite this article

Chen,O. (2025). Visual Art Therapy for internalising disorders with communication deficiency: a systematic review. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(9),9-15.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., & Rescorla, L. A. (2017). Empirically based assessment and taxonomy of psychopathology for ages 1½–90+ years: Developmental, multi-informant, and multicultural findings.Comprehensive Psychiatry, 79, 4–18. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.03.006

[2]. Forns, M., Abad, J., & Kirchner, T. (2011). Internalizing and externalizing problems. In Springer eBooks (pp. 1464–1469). https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_261

[3]. Haftgoli, N., Favrat, B., Verdon, F., Vaucher, P., Bischoff, T., Burnand, B., & Herzig, L. (2010). Patients presenting with somatic complaints in general practice: depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders are frequent and associated with psychosocial stressors.BMC Family Practice, 11(1). https: //doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-67

[4]. Struijs, S. Y., Lamers, F., Vroling, M. S., Roelofs, K., Spinhoven, P., & Penninx, B. W. (2017). Approach and avoidance tendencies in depression and anxiety disorders.Psychiatry Research, 256, 475–481. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.010

[5]. Olatunji, B. O., Naragon-Gainey, K., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B. (2013). Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta‐analysis.Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 20(3), 225–257. https: //doi.org/10.1037/h0101719

[6]. Eaton, N. R., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Carragher, N., & Krueger, R. F. (2015). Transdiagnostic factors of psychopathology and substance use disorders: a review.Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(2), 171–182. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-1001-2

[7]. Chen, X., Li, F., Zuo, H., & Zhu, F. (2025). Trends in Prevalent Cases and Disability‐Adjusted Life‐Years of Depressive Disorders Worldwide: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study from 1990 to 2021.Depression and Anxiety, 42(1). https: //doi.org/10.1155/da/5553491

[8]. Bie, F., Yan, X., Xing, J., Wang, L., Xu, Y., Wang, G., Wang, Q., Guo, J., Qiao, J., & Rao, Z. (2024). Rising global burden of anxiety disorders among adolescents and young adults: trends, risk factors, and the impact of socioeconomic disparities and COVID-19 from 1990 to 2021.Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1489427

[9]. Luo, J., Tang, L., Kong, X., & Li, Y. (2024). Global, regional, and national burdens of depressive disorders in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years from 1990 to 2019: A trend analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 92, 103905. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103905

[10]. Blomqvist, I., Blom, E. H., Hägglöf, B., & Hammarström, A. (2019). Increase of internalized mental health symptoms among adolescents during the last three decades.European Journal of Public Health,29(5), 925–931. https: //doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz028

[11]. Rosenthal, S. R., Buka, S. L., Marshall, B. D., Carey, K. B., & Clark, M. A. (2016). Negative experiences on Facebook and depressive symptoms among young adults.Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 510–516. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.023

[12]. Maras, D., Flament, M. F., Murray, M., Buchholz, A., Henderson, K. A., Obeid, N., & Goldfield, G. S. (2015). Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth.Preventive Medicine,73, 133–138. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.029

[13]. Karrouri, R., Hammani, Z., Benjelloun, R., & Otheman, Y. (2021). Major depressive disorder: Validated treatments and future challenges.World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(31), 9350–9367. https: //doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9350

[14]. Segrin, C. (2000b). Social skills deficits associated with depression.Clinical Psychology Review,20(3), 379–403. https: //doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00104-4

[15]. Hill, E., Tonta, K., Boyes, M., Norbury, C., Griffiths, S., Goh, S., & Ryan, B. (2025). “Why would someone like me with DLD want to sit in a room and talk? How would that make me feel better?!” Developmental Language Disorder and the language demands of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.International Journal of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. 18, 405–424 (2025). https: //doi.org/10.1007/s41811-025-00254-3

[16]. Hu, J., Zhang, J., Hu, L., Yu, H., & Xu, J. (2021). Art therapy: a complementary treatment for mental disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686005

[17]. Haeyen, S., Van Hooren, S., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2015). Perceived effects of art therapy in the treatment of personality disorders, cluster B/C: A qualitative study.The Arts in Psychotherapy, 45, 1–10. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.005

[18]. Hartz, L., & Thick, L. (2005). Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: A comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches.Art Therapy, 22(2), 70–80. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129440

[19]. Zhang, B., Yang, L., Sun, W., Xu, P., Ma, H., & Abdullah, A. B. (2025). The effect of the art therapy interventions to alleviate depression symptoms among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Clinics,80, 100683. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2025.100683

[20]. Støre, S. J., & Jakobsson, N. (2022). The effect of mandala coloring on state anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Art Therapy, 39(4), 173–181. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2021.2003144

[21]. Han, B., Jia, Y., Hu, G., Bai, L., Gains, H., You, S., He, R., Jiao, Y., Huang, K., Cui, L., & Chen, L. (2024b). The effects of visual art therapy on adults with depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta‐analysis.International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 33(5), 1183–1196. https: //doi.org/10.1111/inm.13331

[22]. Lazar, A., Feuston, J. L., Edasis, C., & Piper, A. M. (2018). Making as expression.CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173925

[23]. Riley, S. (2003). Using art therapy to address adolescent depression. InC. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of art therapy, 220-228. Guilford Press.

[24]. Schouten, K. A., Van Hooren, S., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2018). Trauma-focused art therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study.Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(1), 114–130. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712

[25]. Talwar, S. (2006). Accessing traumatic memory through art making: An art therapy trauma protocol (ATTP).The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34(1), 22–35. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.001

[26]. Mochimaru, Y., & Demaine, K. (2022). Digital art therapy and social withdrawal in Japan.Creative Arts in Education and Therapy,8(1), 99–112. https: //doi.org/10.15212/caet/2022/8/16

[27]. Rentz, C. A. (2002). Memories in the Making: Outcome-based evaluation of an art program for individuals with dementing illnesses.American Journal of Alzheimer S Disease & Other Dementias, 17(3), 175–181. https: //doi.org/10.1177/153331750201700310

[28]. Abbing, A., Baars, E. W., De Sonneville, L., Ponstein, A. S., & Swaab, H. (2019). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adult women: a randomized controlled trial.Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–14. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01203

[29]. Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., Van Hooren, S., De Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., & Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials.PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0208716, 1-19. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

[30]. The Psychology of American Abstract Expressionism. (2023).International Journal of Art and Art History, Vol. 11(No. 1), 9–22. https: //doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v11n1p2

[31]. Wild, J., & Gur, R. C. (2008). Verbal memory and treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder.The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(3), 254–255. https: //doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045922

[32]. Mirabella, G. (2015). Is art therapy a reliable tool for rehabilitating people suffering from brain/mental diseases?The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(4), 196–199. https: //doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0374

[33]. Zhang, M., Liu, X., & Huang, Y. (2023b). Does mandala art improve psychological well-being in patients? A systematic review.Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 30(1), 25–36. https: //doi.org/10.1089/jicm.2022.0780

[34]. Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,56(5), 815–822. https: //doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

[35]. Kondo, N., Sakai, M., Kuroda, Y., Kiyota, Y., Kitabata, Y., & Kurosawa, M. (2011). General condition of hikikomori (prolonged social withdrawal) in Japan: Psychiatric diagnosis and outcome in mental health welfare centres.International Journal of Social Psychiatry,59(1), 79–86. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0020764011423611

[36]. Dadashi, N., Mojen, L. K., Ilkhani, M., Nasirie, M., Mirzaee, H. R., & Boozaripour, M. (2025). Effect of mandala art therapy on quality of life in breast cancer patients.Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 26(7), 2533–2540. https: //doi.org/10.31557/apjcp.2025.26.7.2533

[37]. Franklin, M. (1992). Art therapy and self-esteem.Art Therapy,9(2), 78–84. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1992.10758941

[38]. Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M., Vanhala, M., & Gold, C. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: randomised controlled trial.The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(2), 132–139. https: //doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085431