1 Introduction

With the intensification of globalization, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been described as “a hallmark of true global thinking” [21]. It has elevated from being part of corporate missions and strategic goals to a means of achieving corporate legitimacy, purpose, and sustainable development. The fulfillment of CSR is not only a corporate-level activity but also requires the participation of every employee [68]. Employees’ positive reactions to and even participation in corporate CSR initiatives is crucial to the social benefits generated by these activities [48]. However, employees’ attitudes toward CSR vary widely, with a significant number of employees remaining indifferent or even resistant to corporate CSR plans [13]. At the same time, existing literature has predominantly adopted an instrumental perspective, exploring how CSR influences traditional organizational behavior (OB) outcomes such as organizational commitment, organizational identification, and job performance [22], while neglecting employees’ participation in CSR. Specifically, the question of whether corporate CSR practices can inspire CSR-specific outcomes among employees to promote positive social change remains underexplored [17, 22]. Therefore, in the CSR 3.0 era, examining the drivers and mechanisms of employees’ CSR-specific performance is a topic with both theoretical and practical significance.

As the concept of social responsibility continues to be embedded and internalized within organizations, companies are increasingly focusing on formulating policies that integrate CSR with human resource management and employee initiative [38]. This has given rise to Socially Responsible Human Resource Management (SRHRM). SRHRM is not only a component of CSR activities but also a critical tool for successfully implementing CSR [50]. SRHRM refers to a set of organizational practices aimed at recruiting and retaining socially responsible employees, providing CSR-related training, and incorporating employees’ CSR contributions into key management decisions such as promotions, performance evaluations, and compensation [52, 56].

Existing research, based on theories such as social identity theory, person-organization fit theory, and self-determination theory, has preliminarily explored how SRHRM positively influences employees’ organizational commitment, task performance, organizational citizenship behavior, and voice behavior through mechanisms like organizational identification [52, 50], person-organization fit [65], and autonomous and controlled motivation [64]. However, the socialization outcomes of SRHRM remain underexplored [63]. Employees’ CSR-specific performance refers to their role-related or extra-role behaviors in the context of implementing organizational CSR initiatives [59] and represents an extension of their job performance into the domain of CSR activities. Based on this, the present study aims to explore whether and how SRHRM affects employees’ CSR-specific performance.

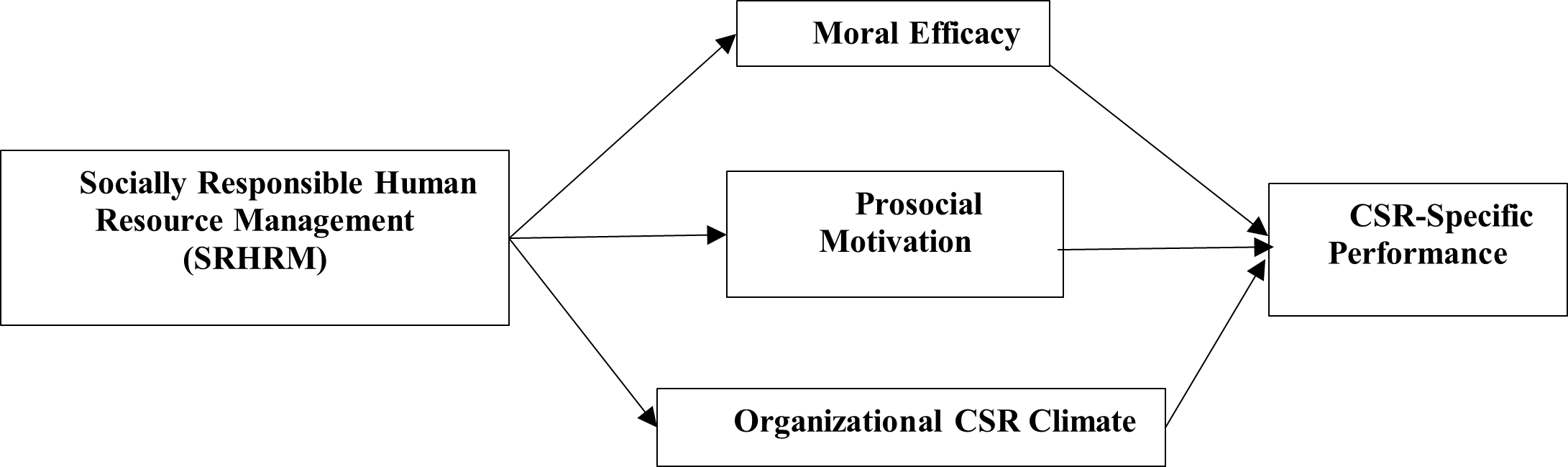

The A (Ability) – M (Motivation) – O (Opportunity) framework [3] provides a suitable theoretical perspective for clarifying the mechanisms through which SRHRM drives employees’ CSR-specific performance. On one hand, the AMO framework is a powerful lens for uncovering the mechanisms of employee performance [28]; on the other hand, SRHRM represents a specialized form of strategic human resource management [52]. Specifically, SRHRM promotes employees’ CSR-specific performance through three mechanisms: “ability,” “motivation,” and “opportunity.” First, regarding the “ability” mechanism, SRHRM emphasizes recruiting and selecting employees who possess awareness and knowledge of social responsibility and provides training to cultivate the necessary skills and knowledge for exhibiting socially responsible behavior [52]. These practices enhance employees’ moral efficacy, thereby boosting their CSR-specific performance. Second, in terms of the “motivation” mechanism, SRHRM practices such as performance evaluations, compensation, rewards, and promotions based on CSR performance motivate employees to complete their tasks in prosocial ways, reinforcing their prosocial motivation and consequently increasing CSR-specific performance. Finally, concerning the “opportunity” mechanism, employees’ CSR-specific performance depends on the organizational support and encouragement they receive. SRHRM sends signals to employees that the organization values social responsibility [63], shaping a CSR-oriented organizational climate that fosters employees’ CSR-specific performance. Therefore, this study posits that moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate respectively represent the ability, motivation, and opportunity mechanisms, acting as parallel mediators for SRHRM’s positive effect on employees’ CSR-specific performance.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, by exploring the role of SRHRM in promoting employees’ CSR-specific performance, this research goes beyond the instrumental perspective that dominates existing studies [63, 22] and extends the focus to social outcomes, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of SRHRM’s effects. Second, based on the AMO framework, this study clarifies the parallel mediating mechanisms of moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate. This not only expands the applicability of the AMO framework but also provides deeper insights into the black box of SRHRM’s influence on employees. Finally, this study offers practical implications for HRM in the context of corporate social responsibility, encouraging organizational managers to recognize the importance of implementing HRM practices grounded in CSR. Such practices can leverage employees’ critical role in the successful implementation of CSR initiatives.

2 Theoretical Foundations and Research Hypotheses

2.1 Socially Responsible Human Resource Management (SRHRM)

Shen and Zhu (2011) formally introduced the concept of SRHRM, suggesting that it is as effective in organizational strategic development as other progressive HRM systems. They divided SRHRM into three main components: legal compliance HRM related to labor laws, employee-oriented HRM, and general CSR-promoting HRM. They emphasized that socially responsible HRM should comply with legal requirements, focus on employee needs, and encourage employees to participate in CSR initiatives benefiting external stakeholders. Similarly, Kundu and Gahlawat (2015) underscored the critical role of employees in advancing CSR initiatives by defining SRHRM as HR activities that aim to enhance employees’ participatory roles in CSR, viewing employees as both disseminators and recipients of CSR practices. In addition to its employee-centric approach and emphasis on employee participation in CSR initiatives, SRHRM also incorporates a significant focus on equality. The equality perspective requires organizations to reasonably consider gender factors when implementing SRHRM. For instance, organizations should provide equal employment opportunities in the workplace, balance work and family responsibilities, offer specific support to female employees, enhance women’s involvement in decision-making and their voice in discussions, and provide flexible working hours for female employees [42]. Building on this, Shen and Benson (2016) defined SRHRM as CSR-related policies and practices aimed at employees. These include not only offering competitive salaries and working conditions but also recruiting and retaining socially responsible employees, providing CSR training, and considering employees’ social contributions in promotions, performance evaluations, and compensation.

2.2 SRHRM and Employees’ CSR-specific Performance

Previous studies have shown that SRHRM has a positive impact on employee performance, such as increasing organizational belongingness, trust, and commitment [50, 52], as well as enhancing employee attraction, retention, and motivation [30, 42]. This study argues that SRHRM positively influences employees’ CSR-specific performance. CSR-specific performance refers to the effectiveness of employees’ behaviors in fulfilling tasks related to CSR projects. It includes in-role CSR performance, which pertains to behaviors related to CSR that are formally stipulated, rewarded, or sanctioned, and extra-role CSR performance, which consists of voluntary behaviors supporting CSR projects but not explicitly recognized by formal reward systems [59].

First, SRHRM encourages organizations to recruit and retain socially responsible employees, increasing the likelihood of hiring employees with positive attitudes toward CSR [51]. These employees inherently possess strong moral awareness and ethical standards, motivating them to engage in socially responsible behaviors, both within their job responsibilities and in extra-role activities that support the organization’s CSR efforts. Studies have shown that employees’ perceptions of positive CSR practices can trigger voluntary environmental behaviors [1, 57] and pro-environmental workplace behaviors [54]. Second, Ellis (2009) noted that employees’ lack of awareness of CSR could negatively impact their engagement. Providing CSR-related training equips employees with the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for both in-role and extra-role CSR performance, reinforcing the organizational CSR values and ensuring a solid capability foundation for CSR-specific behaviors [51]. Finally, considering employees’ social contributions in performance appraisals, promotions, and salary adjustments strengthens employees’ recognition of and commitment to CSR. Such practices convey organizational support and acknowledgment of employees’ social contributions [50], signaling a long-term employee-organization relationship and investment. Based on the principle of reciprocity, this approach motivates employees to increase their engagement in CSR-related work and their proactive extra-role behaviors, thereby maximizing their CSR-specific performance.

Additionally, we can analyze the process through which SRHRM exerts its influence. First, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a globally accepted norm, and employees often evaluate their companies based on CSR performance. Consequently, companies that successfully engage in CSR are more likely to receive positive recognition from employees, thereby enhancing their organizational identification [6, 15]. When organizations implement socially responsible human resource management, such as evaluating and rewarding employees’ social performance, they convey an organizational message aligned with CSR norms, which actively strengthens employees’ sense of organizational identification [50]. Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that employees who identify with their organizations tend to fulfill their job obligations through task performance and extra-role behaviors, such as pro-environmental actions, exerting additional effort to promote the collective interests, values, and goals of the organization [36, 50, 57].

Second, existing research shows that employees who perceive their organizations as socially responsible are more likely to develop a sense of identification and moral obligation toward the organization, fostering an emotional connection with it. This manifests as strong affective commitment [52]. Employees who exhibit higher levels of affective commitment toward their organizations are more motivated to undertake CSR-specific task performance and extra-role behaviors. These behaviors, in turn, support the organization in achieving its CSR objectives [59].

Finally, through the implementation of SRHRM, organizations can integrate their endorsed values into organizational systems and encourage employees to embody these values in their daily actions, thereby communicating CSR values to employees. In doing so, organizations cultivate a socially responsible environment, which reflects employees’ shared perception of a workplace dedicated to addressing the interests of various stakeholders [51]. Vlachos et al. (2014) demonstrated that employees who perceive their companies as socially and environmentally responsible are more likely to contribute ideas, actively participate, and willingly support organizational CSR initiatives, further enhancing their CSR-specific performance. Additionally, Tian and Robertson (2019) found that employees’ perceptions of CSR influence their environmentally responsible behaviors, providing indirect empirical support for our hypothesis.

In summary, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Socially responsible human resource management is positively correlated with employees’ CSR-specific performance.

2.3 The Mediating Role of Moral Efficacy

Competence refers to the knowledge, skills, and abilities that enable employees to effectively complete a task and fulfill their responsibilities. It is one of the three main pathways through which human resource management influences employee performance [28]. This study uses moral efficacy in moral contexts to represent employees’ competence. Moral efficacy is defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to organize and mobilize motivation, cognitive resources, means, and action processes to achieve moral performance within a specific moral domain [25, 32]. Moral efficacy is malleable and can be developed through successful experiences, modeling, verbal persuasion, and psychological/emotional arousal [4, 27].

Human resource management enables organizations to hire employees with the required knowledge and skills, while training programs help enhance the abilities of existing employees [53]. This aligns with the “make” and “buy” approaches proposed by Youndt et al. (2004) to increase employees’ KSAs (knowledge, skills, and abilities). Empirical studies have shown that specific-oriented human resource management practices can enhance employees’ specific efficacy in various ways during organizational implementation [33, 67]. SRHRM encompasses corporate social responsibility, HRM ethics, and employee-oriented HRM practices [52]. Its ethical characteristics, such as fairness, trust, and care [69], help organizations establish both internal and external moral environments, thereby improving employees’ moral efficacy.

Specifically, recruiting and retaining socially responsible employees—who tend to possess high moral standards [69]—enhances employees’ moral awareness and moral beliefs when faced with ethical decisions. In addition to offering employees superior compensation and working conditions to safeguard their interests, organizations also provide CSR-related training [50]. Such training enables employees to repeatedly practice the skills needed to fulfill social responsibilities, actively engage in corporate social responsibility practices, and accumulate successful experiences, thus enhancing their moral efficacy. Furthermore, organizations consider employees’ contributions to society in performance appraisals, promotions, and salary increases, encouraging ethical behavior and motivating employees to continuously acquire knowledge and skills related to social responsibility. By reinforcing and rewarding such behaviors, organizations provide employees with more opportunities to gain successful experiences in ethical behavior, thereby boosting their moral efficacy. Lastly, when organizations implement SRHRM practices, they not only offer employees favorable compensation and working conditions but also fulfill social responsibilities to external stakeholders. These actions, as events influencing employees’ perceptions of first-party and third-party fairness, evoke positive emotions such as happiness, excitement, and pride [69], further stimulating employees’ moral efficacy.

Perceived efficacy, as a task-specific motivational construct, has been demonstrated to influence individuals’ choices of actions as well as the effort and persistence dedicated to executing those actions [2, 4]. Ample empirical evidence supports the critical role of efficacy across various levels of analysis [32]. Domain-specific literature reveals that employees with higher levels of task-specific efficacy are more likely to engage in behaviors associated with their efficacy beliefs [11]. For example, higher creative self-efficacy leads to an increase in creative workplace behaviors [58]. As an efficacy belief specifically linked to moral behavior, moral efficacy strengthens employees’ intentions to engage in ethical actions [26]. Individuals with higher moral efficacy are more likely to translate moral judgment and inclinations into moral behavior [49]. In fact, research has shown that moral efficacy can encourage more prosocial behaviors, such as organizational citizenship behaviors [66]. Similarly, employees’ CSR performance, which also encompasses prosocial behavior, is influenced by their moral efficacy. In summary, when organizations implement SRHRM practices, the ethical characteristics they demonstrate—such as fairness, trust, and care—contribute to building a favorable and equitable work environment. This environment enhances employees’ moral competence, and their perception of moral capability becomes a crucial driving force for improving CSR-specific performance. Therefore, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H2: Moral efficacy mediates the positive relationship between SRHRM and employees’ CSR-specific performance.

2.4 The Mediating Role of Prosocial Motivation

The second determinant of employee performance is motivational performance. According to Lepak et al. (2006), motivation refers to an individual’s choice to exert effort toward achieving a goal, as well as the degree and duration of that effort. Other scholars define it as an individual’s desire and willingness to act [9]. Considering that this study focuses on SRHRM practices, which differ from general HRM practices by embodying corporate social responsibility (CSR), we use employees’ prosocial motivation to represent motivational performance. Prosocial motivation is defined as the willingness to consider others’ interests and to expend effort on their behalf [23]. Individuals with high prosocial motivation tend to prioritize protecting and promoting the welfare of others [40]. Existing literature provides two perspectives on prosocial motivation. One conceptualizes it as a stable trait-like construct, while the other views it as a state-like construct that varies with time and context [23, 24]. In this study, we conceptualize prosocial motivation as a state-like construct influenced by the work environment and situational triggers.

As an organizational-level contextual factor, SRHRM practices can enhance employees’ prosocial motivation in several ways: (1) When companies actively engage in CSR projects and implement SRHRM, they go beyond fulfilling economic and legal obligations by considering the moral and social responsibilities toward their employees and a broader range of stakeholders. CSR involves formulating policies and strategies that account for the organization’s impact on diverse stakeholders, including employees, communities, and the environment. This stakeholder-oriented approach emphasizes promoting and safeguarding others’ welfare, which positively enhances employees’ prosocial motivation in such organizational contexts [71]. (2) Organizations recognize and reward employees’ contributions, such as considering their societal impact during performance appraisals and promotions. This positive feedback encourages employees to act ethically [60], enhances their sense of social responsibility, and motivates them to contribute to broader community welfare, thereby fostering higher levels of prosocial motivation [40]. (3) Empirical studies suggest that socially responsible HRM practices increase employees’ organizational identification [50], foster emotional attachment and affective commitment to the organization [52], and enhance employees’ sense of belonging. To maintain alignment with the organization, employees are likely to exhibit behaviors consistent with its defining characteristics, including heightened prosocial motivation. (4) Research has also shown that when employees perceive their organization’s proactive efforts in CSR, they are more likely to further enhance their prosocial motivation [44].

Studies on prosocial motivation in organizational literature indicate that employees with prosocial motivation are more sensitive to the needs and perspectives of others, including colleagues, supervisors, suppliers, and customers, thereby improving their performance and productivity [5]. Prosocial motivation is a powerful driver of volunteering and helping behaviors. Employees with high prosocial motivation or a strong desire to care for and assist others naturally engage in prosocial behaviors that benefit the community and others [19]. Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that prosocial motivation positively influences employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors, community citizenship behaviors, and other prosocial actions [40, 44]. At the employee level, CSR behaviors target the welfare of both internal and external stakeholders, fundamentally constituting prosocial behaviors driven by prosocial motivation [16]. Based on the above reasoning, we posit that SRHRM practices enhance employees’ prosocial motivation. When employees care about the welfare of their organization, they are more likely to invest greater effort in achieving organizational goals through CSR behaviors, thereby improving their CSR-specific performance. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Prosocial motivation mediates the positive relationship between SRHRM and employees’ CSR-specific performance.

2.5 The Mediating Mechanism of Organizational CSR Climate

The third determinant of employee performance is opportunity (O) performance. Scholars have noted that even if employees possess the ability and motivation to work toward organizational goals, they cannot achieve their expectations without appropriate opportunities to demonstrate their efforts [37]. While there is no definitive description of what these opportunities are or what they should look like, Blumberg and Pringle (1982) were the first to incorporate the opportunity dimension into the framework of factors influencing employee performance. They provided examples of opportunities, such as whether employees have the necessary tools and equipment to execute tasks, and whether the company’s working conditions and culture facilitate the required behaviors. They further emphasized that the work environment is one of the variables that can characterize opportunity, which is an environmental factor that enables or constrains employee performance, beyond their direct control. This study uses the organizational CSR climate to represent employees’ contribution opportunities. The organizational CSR climate refers to employees’ shared perceptions of how the organization addresses the interests of various stakeholders and constitutes an organizational climate specific to CSR. It aligns with the CSR-oriented human resource management practices and CSR-specific performance examined in this study. Existing research indicates that an organizational CSR climate enhances employees’ support for organizational CSR initiatives. It creates opportunities by providing a supportive environment that enables employees to engage in socially responsible behaviors [51].

Organizational climate is defined as “shared perceptions of the surrounding environment” [46] and represents the quantification of organizational culture, largely derived from the adoption of organizational policies. Consequently, organizational climate evolves over time, especially when organizational policies change [45]. Human resource management practices are a primary factor in shaping organizational climate [20, 39]. Employees interpret their work environment based on which behaviors are acceptable and the consequences of these behaviors, thereby guiding their actions [12]. A successful organization, in addition to maximizing economic benefits, also cares about stakeholders such as customers, employees, and communities, and embraces a culture that values corporate social responsibility commitments. Shen and Zhang (2019) empirically demonstrated that by adopting SRHRM practices, organizations can integrate their endorsed values into organizational systems and encourage employees to reflect these values in their daily behaviors, thereby communicating CSR values to employees. In this way, the organization develops its CSR climate.

Organizational climate affects employees’ cognitive and emotional states, prompting them to act in certain ways and motivating behaviors that are required and accepted in the workplace [46]. In this study, the organizational CSR climate influences employees’ perceptions of CSR and fosters attitudes toward CSR, aligning employees’ values with the organization’s advocated CSR values. Furthermore, the organizational CSR climate provides a supportive environment for employees who are capable and willing to engage in CSR, offering them opportunities to participate in organizational CSR initiatives, thereby enhancing their individual CSR-specific performance. In summary, organizational climate serves as a critical foundational mechanism linking human resource management practices to employees’ work attitudes and behaviors [39]. Previous research has indicated that SRHRM practices can cultivate an organizational CSR climate, thereby increasing employees’ support for organizational CSR initiatives [51]. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: The organizational CSR climate mediates the positive relationship between SRHRM and employees’ CSR-specific performance.

In conclusion, the hypothesized model of this study is illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model

3 Research Methodology

3.1 Research Sample

The participants in this survey were primarily employees from enterprises located in Central and South China, encompassing industries such as pharmaceutical manufacturing, non-ferrous metal smelting and processing, and automobile manufacturing. A combination of online and offline methods was used to collect sample data. The online method involved creating a questionnaire link via Questionnaire Star and distributing it to enterprise employees through email, social media platforms such as WeChat Moments, or other electronic channels. Each respondent was assigned a unique ID number based on the last four digits of their mobile phone number combined with the initials of their name, enabling the matching of questionnaires collected at different time points. The offline method involved the distribution of paper questionnaires on-site. With the assistance of colleagues from the enterprises’ human resources departments, each participating employee was assigned a unique ID number. Staff members explained the research purpose to respondents and assured them of the anonymity of the survey.

To reduce common method bias, the study collected data at two time points, approximately one month apart. At Time Point 1, data were collected on employees’ demographic variables, their evaluations of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM), self-reported moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and perceptions of the organizational CSR climate. A total of 459 valid questionnaires were retrieved. At Time Point 2, data on employees’ self-reported CSR-specific performance were collected. By matching the questionnaires from the two time points, a total of 331 valid paired questionnaires were obtained, yielding a response rate of 72.11%.

In the final sample of 331 employees, 150 were female, accounting for 45.3% of the sample. The average age of participants was 33.19 years (SD = 7.784). Employees with a college degree or higher comprised 81.1% of the sample, while 137 participants (41.4%) held regular employee positions.

3.2 Variable Measurement

The measurement scales for the variables in this study were all adapted from well-established foreign scales. Given the emphasis on contextual characteristics in organizational behavior research, the original variables were contextualized for the Chinese setting through a translation-back translation process. The scales for socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM), moral efficacy, organizational CSR climate, and employees’ prosocial identification used a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 to 5 ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The scales for prosocial motivation and CSR-specific performance used a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 to 7 ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

3.2.1 Socially Responsible Human Resource Management (Time Point 1)

This scale was adapted from Shen and Benson (2016) and consists of six items. Representative items include: “When recruiting employees, the enterprise I work for considers whether the applicant’s values align with the CSR values recognized by the enterprise” and “The enterprise I work for provides appropriate CSR training to make CSR a core organizational value.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.926.

3.2.2 Moral Efficacy (Time Point 1)

This scale was adapted from Hannah and Avolio (2010) with a prompt stating: “Considering your knowledge, skills, and abilities, indicate your confidence in performing the following tasks.” It consists of five items, with representative items such as: “I am confident in taking decisive action when making moral/ethical decisions.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.806.

3.2.3 Prosocial Motivation (Time Point 1)

This scale was adapted from Grant and Adam (2008) to measure “Why are you motivated to do your job?” It consists of four items, with representative items such as: “Because I want to have a positive impact on others.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.950.

3.2.4 Organizational CSR Climate (Time Point 1)

This scale was adapted from Shen and Zhang (2019) and consists of five items. A representative item is: “The company expects employees to do the right thing to support social welfare initiatives.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.702.

3.2.5 CSR-Specific Performance (Time Point 2)

This scale was adapted from Vlachos et al. (2014) and includes two dimensions: in-role CSR-specific performance and extra-role CSR-specific performance. The in-role dimension includes three items, such as: “I have contributed many ideas to improve my organization’s CSR initiatives.” The extra-role dimension includes four items, such as: “My work behavior aligns with the standards of the company’s CSR initiatives.” The overall Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.911.

3.2.6 Control Variables (Time Point 1)

Consistent with previous research, this study set employees’ gender, age, educational background, and job level as control variables to eliminate potential alternative explanations. Specifically, age was measured in years; gender was coded as 1 for male and 2 for female; educational background was coded as 1 for high school or below, 2 for associate degree, 3 for bachelor’s degree, and 4 for master’s degree or above; and job level was coded as 1 for regular employee, 2 for junior manager, 3 for middle manager, and 4 for senior manager.

4 Data Analysis and Results

4.1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To test the discriminant validity of the variables in this study, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on SRHRM, moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, organizational CSR climate, and CSR-specific performance. As shown in Table 1, the hypothesized five-factor model demonstrated the best fit (2/df = 2.659, RMSEA = 0.071, CFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.910), with all fit indices meeting the required thresholds. Compared with other measurement models, the five-factor model exhibited significant differences, indicating good discriminant validity for the focal variables in this study.

Table 1. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Model |

χ2 |

df |

χ2/df |

RMSEA |

CFI |

TLI |

Five-Factor (SRHRM; MOE; PRM; CRE; CSRP) |

835.082 |

314 |

2.659 |

0.071 |

0.920 |

0.910 |

Four-Factor (SRHRM+CRE; MOE; PRM; CSRP) |

1057.767 |

318 |

3.326 |

0.084 |

0.886 |

0.874 |

Three-Factor (SRHRM+CRE+MOE; PRM; CSRP) |

1581.072 |

321 |

4.925 |

0.109 |

0.806 |

0.788 |

Two-Factor (SRHRM+CRE+MOE+PRM; CSRP) |

2596.950 |

323 |

8.040 |

0.146 |

0.649 |

0.619 |

One-Factor (SRHRM+MOE+PRM+CRE+CSRP) |

3126.244 |

324 |

9.649 |

0.162 |

0.568 |

0.532 |

Note: SRHRM represents socially responsible human resource management; MOE represents moral efficacy; PRM represents prosocial motivation; CRE represents organizational CSR climate; CSRP represents CSR-specific performance.

4.2 Descriptive Statistical Analysis

The mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients of the study variables are presented in Table 2. The results show that SRHRM is significantly positively correlated with CSR-specific performance (r = 0.501, p < 0.001); SRHRM is also significantly positively correlated with moral efficacy (r = 0.336, p < 0.001), prosocial motivation (r = 0.459, p < 0.001), and organizational CSR climate (r = 0.542, p < 0.001). Additionally, moral efficacy (r = 0.562, p < 0.001), prosocial motivation (r = 0.616, p < 0.001), and organizational CSR climate (r = 0.526, p < 0.001) are positively correlated with CSR-specific performance. These correlation analyses provide preliminary support for further exploration of the relationships between variables.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis (N = 331)

Variable |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

1. Gender |

1.45 |

0.499 |

— |

|||||||

2. Age |

33.19 |

7.784 |

-0.157** |

— |

||||||

3. Education Level |

2.25 |

0.837 |

0.199*** |

-0.129* |

— |

|||||

4. Job Level |

1.69 |

0.666 |

-0.247*** |

0.458*** |

0.059 |

— |

||||

5. SRHRM |

3.877 |

0.695 |

0.064 |

-0.184*** |

-0.131* |

-0.085 |

— |

|||

6. Moral Efficacy |

3.956 |

0.475 |

-0.062 |

0.065 |

-0.064 |

0.141* |

0.336*** |

— |

||

7. Prosocial Motivation |

5.739 |

0.944 |

0.001 |

-0.070 |

0.019 |

0.043 |

0.459*** |

0.408*** |

— |

|

8. Organizational CSR Climate |

3.799 |

0.587 |

0.051 |

-0.037 |

-0.023 |

0.018 |

0.542*** |

0.443*** |

0.426*** |

— |

9. CSR-Specific Performance |

5.509 |

0.839 |

-0.080 |

0.002 |

-0.179** |

0.060 |

0.501*** |

0.562*** |

0.616*** |

0.526*** |

Note: * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, *** indicates p < 0.001; SRHRM represents Socially Responsible Human Resource Management.

4.3 Hypothesis Testing

This study employed hierarchical regression analysis to examine the mechanism by which socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) influences employees’ CSR-specific performance. The results are presented in Table 3. Controlling for gender, age, education level, and job position, Model 1 shows that SRHRM has a significant positive effect on CSR-specific performance (B = 0.608, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. According to Models 3, 4, and 5, SRHRM significantly positively affects moral efficacy (B = 0.254, p < 0.001), prosocial motivation (B = 0.645, p < 0.001), and organizational CSR climate (B = 0.472, p < 0.001). Furthermore, when moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate are included in Model 2, the positive effect of SRHRM on CSR-specific performance remains significant (B = 0.158, p < 0.01), albeit with a reduced effect size. This indicates that moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate mediate the positive impact of SRHRM on CSR-specific performance.

To further validate the mediation effects, this study applied Bootstrap analysis, with results shown in Table 4. The mediation effect of moral efficacy is 0.130, with a confidence interval of [0.080, 0.189], excluding zero, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. The mediation effect of prosocial motivation is 0.211, with a confidence interval of [0.138, 0.295], excluding zero, supporting Hypothesis 3. The mediation effect of organizational CSR climate is 0.110, with a confidence interval of [0.038, 0.193], excluding zero, supporting Hypothesis 4.

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis Results (N = 331)

Variable |

CSR-Specific Performance |

Moral Efficacy |

Prosocial Motivation |

Organizational CSR Climate |

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

|

Gender |

-0.105 |

-0.074 |

-0.045 |

-0.051 |

-0.037 |

Age |

0.003 |

0.001 |

0.004 |

-0.003 |

0.003 |

Education Level |

-0.097 |

-0.138*** |

0.003 |

0.097 |

0.036 |

Job Position |

0.111 |

0.089 |

0.093* |

0.128 |

0.053 |

SRHRM |

0.608*** |

0.158** |

0.254*** |

0.645*** |

0.472*** |

Moral Efficacy |

0.511*** |

||||

Prosocial Motivation |

0.327*** |

||||

Organizational CSR Climate |

0.232*** |

||||

R2 |

0.278*** |

0.568*** |

0.154*** |

0.225*** |

0306 |

F |

24.450 |

51.558 |

11.514 |

18.385 |

27.967 |

Note: * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, *** indicates p < 0.001; SRHRM represents Socially Responsible Human Resource Management.

5 Conclusion and Discussion

5.1 Research Conclusions

This study, based on the AMO (Ability-Motivation-Opportunity) framework, explores the driving effects and mechanisms of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) on employees’ CSR-specific performance. Data collected from 331 questionnaires at three time points demonstrate that SRHRM has a significant positive impact on employees’ CSR-specific performance. Moreover, moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate, representing ability, motivation, and opportunity mechanisms respectively, mediate the positive effects of SRHRM on employees’ CSR-specific performance.

Table 4. Mediation Effect Analysis of SRHRM on CSR-Specific Performance (N = 331)

Mediation Path |

effect |

BootSE |

95% Confidence Interval |

|

LLCI |

ULCI |

|||

Moral Efficacy Mediation Effect |

0.130 |

0.028 |

0.080 |

0.189 |

Prosocial Motivation Mediation Effect |

0.211 |

0.041 |

0.138 |

0.295 |

Organizational CSR Climate Mediation Effect |

0.110 |

0.040 |

0.038 |

0.193 |

5.2 Theoretical Contributions

Firstly, this study enhances our understanding of the outcomes influenced by SRHRM. Existing SRHRM literature primarily focuses on its effects on traditional organizational behavior (OB) outcomes, such as organizational commitment [52], organizational identification [41], well-being [63], moral voice [64], and job performance [31]. However, limited research has examined the impact of SRHRM on CSR-related OB outcomes [22]. Employees, as a critical stakeholder group, play a pivotal role in the social benefits generated by corporate social responsibility initiatives [48]. Nevertheless, there has been scant attention to whether and how SRHRM influences employees’ individual social responsibility behaviors. In recent years, scholars have called for research that goes beyond the instrumental perspective of SRHRM to explore its broader social impact [63]. Addressing this gap, this study confirms that SRHRM enhances employees’ CSR-specific performance, thereby enriching our understanding of the drivers of employees’ social responsibility behaviors and broadening the overall perspective on the instrumental and social impacts of SRHRM.

Secondly, by introducing the AMO framework into the SRHRM research domain, this study offers a new perspective for elucidating the mechanisms through which SRHRM promotes employees’ CSR-specific performance. Current research primarily draws on theories such as social identity theory, person-organization fit theory, self-determination theory, and social information processing theory to investigate how SRHRM influences employees through mechanisms like organizational identification [52, 50], person-organization fit, autonomous and controlled motivation [64], and perspective-taking [63]. However, CSR-specific performance extends employees’ job performance into the realm of social responsibility behaviors, and the AMO framework provides a robust lens for uncovering the mechanisms behind employee performance [28]. Existing studies have yet to leverage this theoretical framework to delve into how SRHRM shapes and enhances employees’ abilities, motivations, and opportunities, thus improving their behavioral performance. By using moral efficacy, prosocial motivation, and organizational CSR climate to represent ability, motivation, and opportunity mechanisms, this study thoroughly examines the triple influence mechanisms of SRHRM on employees’ CSR-specific performance. This not only broadens the application scenarios of the AMO framework but also enriches our understanding of the new mechanisms through which SRHRM impacts employee behavior outcomes.

5.3 Practical Implications

The managerial implications of this study lie in guiding managers on how to foster employees’ individual-level social responsibility behaviors through the implementation of SRHRM. Firstly, from the perspective of human resource management, enterprises should recognize the importance of integrating corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies into HRM practices and actively adopt employee-centered, socially responsible HRM approaches. For example, during recruitment, companies should consider candidates’ CSR values and retain employees who exhibit social responsibility. Providing CSR-related training to employees can enhance their knowledge and skills in this area. Furthermore, employee performance evaluations should include CSR-specific performance, linking it to promotions and rewards. Secondly, moral efficacy serves as a key mediating mechanism through which SRHRM positively impacts employees’ CSR-specific performance. Managers should focus on cultivating employees’ confidence in their ability to carry out ethical behaviors within the organization. Effective communication and opportunities to practice ethical behaviors can enhance employees’ moral efficacy, equipping them with the “ability” to demonstrate CSR-specific performance. Thirdly, given the critical role of prosocial motivation as a mediating factor, organizations can use assessment tools during recruitment to identify and select candidates with prosocial traits. Training programs can then be employed to further stimulate employees’ prosocial motivation, thereby preparing a “motivation” mechanism for employees to exhibit CSR-specific performance. Finally, the study highlights that organizational CSR climate provides opportunities for employees’ CSR-specific performance. Enterprises should strive to engage in ongoing CSR activities and communicate their CSR values to employees. Over time, employees will develop a shared understanding of corporate CSR values, fostering an organizational CSR climate [35].

5.4 Research Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) Although data were collected at three time points, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to directly establish causal relationships between variables. Future research could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to strengthen the causal inferences between variables. (2) This study was conducted within the Chinese context and did not consider the influence of cultural factors. Future studies could conduct cross-cultural research to explore the moderating role of cultural factors. (3) While investigating the internal mechanisms of how SRHRM influences employees’ CSR-specific performance, this study focused solely on the AMO framework to explore three potential mediating mechanisms. Future research could adopt other theoretical perspectives, such as psychological need satisfaction, to uncover additional pathways of influence.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71972185) and the Hunan Provincial Social Science Review Committee Project (XSP22YBZ139).

References

[1]. Afsar, B., Al-Ghazali, B. M., Rehman, Z. U., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). The moderating effects of employee corporate social responsibility motive attributions (substantive and symbolic) between corporate social responsibility perceptions and voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 769-785.

[2]. Alexander, D., & Stajkovic, A. (2006). Development of a core confidence-higher order construct. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1208-1224.

[3]. Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., et al. (2000). Manufacturing Advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

[4]. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

[5]. Bendell, B. L. (2017). I don’t want to be green: Prosocial motivation effects on firm environmental innovation rejection decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(2), 277-288.

[6]. Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2006). Identity, identification, and relationship through social alliances. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 128-137.

[7]. Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder-company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 257-272.

[8]. Blumberg, M., & Pringle, C. D. (1982). The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Academy of Management Review, 7(4), 560-569.

[9]. Bos Nehles, A. C., Van Riemsdijk, M. J., & Kees Looise, J. (2013). Employee perceptions of line management performance: Applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 861-877.

[10]. Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203-221.

[11]. Bradley, P. O., Kai, C. Y., Jeffrey, S. B., Jianghua, M., & David, W. H. (2018). The impact of leader moral humility on follower moral self-efficacy and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 146-163.

[12]. Burke, M. J., Borucki, C. C., & Hurley, A. E. (1992). Reconceptualizing psychological climate in a retail service environment: A multiple-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(5), 717-729.

[13]. Cao, Y., Pil, F. K., & Lawson, B. (2021). Signaling and social influence: The impact of corporate volunteer programs. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(2), 183-196.

[14]. Ciocirlan, C. E. (2017). Environmental workplace behaviors: Definition matters. Organization & Environment, 30(1), 51-70.

[15]. Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(1), 19-33.

[16]. Crilly, D., Schneider, S. C., & Zollo, M. (2008). Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior. European Management Review, 5(3), 175-190.

[17]. De Roeck, K., & Maon, F. (2016). Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 609-625.

[18]. Ellis, A. D. (2009). The impact of corporate social responsibility on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2009, No. 1, pp. 1-6). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

[19]. Finkelstein, M. A., Penner, L. A., & Brannick, M. T. (2005). Motive role identity, and prosocial personality as predictors of volunteer activity. Social Behavior & Personality, 33(4), 403-418.

[20]. Gelade, G., & Ivery, M. (2003). The impact of human resource management and work climate on organizational climate. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 383-404.

[21]. Gjølberg, M. (2009). Measuring the immeasurable?: Constructing an index of CSR practices and CSR performance in 20 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1), 10-22.

[22]. Gond, J. P., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 225-246.

[23]. Grant, A., & Adam, M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48-58.

[24]. Grant, A., & Berg, J. (2011). Prosocial Motivation at Work: When, Why, and How Making a Difference Makes a Difference. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[25]. Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 663-685.

[26]. Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2014). Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(2), 277-279.

[27]. Hannah, S. T., & Avolio, B. J. (2010). Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research, 62(4), 291-310.

[28]. Jiang, K., Chuang, C. H., & Chiao, Y. C. (2015). Developing collective customer knowledge and service climate: The interaction between service-oriented high-performance work systems and service leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1089-1106.

[29]. Kim, C. H., & Scullion, H. (2013). The effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on employee motivation: A cross-national study. Poznan University of Economics Review, 13(2), 5-30.

[30]. Kundu, S. C., & Gahlawat, N. (2015). Socially responsible HR practices and employees’ intention to quit: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Human Resource Development International, 18(4), 387-406.

[31]. Lee, B. Y., Kim, T. Y., Kim, S., Liu, Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). Socially responsible human resource management and employee performance: The roles of perceived external prestige and employee human resource attributions. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(4), 828-845.

[32]. Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47-57.

[33]. Lee, H. W., Pak, J., Kim, S., & Li, L. (2016). Effects of human resource management systems on employee proactivity and group innovation. Journal of Management, 45(2), 819-846.

[34]. Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y., & Harden, E. E. (2006). A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Research in Personnel & Human Resources Management, 25(6), 217-271.

[35]. Lin, Y. T., Liu, N. C., & Lin, J. W. (2022). Firms’ adoption of CSR initiatives and employees’ organizational commitment: Organizational CSR climate and employees’ CSR-induced attributions as mediators. Journal of Business Research, 140, 626-637.

[36]. Manika, D., Wells, V. K., Gregory-Smith, D., & Gentry, M. (2015). The impact of individual attitudinal and organisational variables on workplace environmentally friendly behaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(4), 663-684.

[37]. Meijerink, J. G., & Nehles, A. C. (2018). The effect of Strength-Based Talent Management on employee performance: The impact of employees’ ability, motivation and opportunity to perform. University of Twente.

[38]. Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 805-824.

[39]. Mossholder, K. W., Richardson, H. A., & Settoon, R. P. (2011). Human resource management systems and helping in organizations: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 33-52.

[40]. Nathan, E., Alexander, N., Abby, J. Z., & Steven, S. Z. (2019). The relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ internal and external community citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of prosocial motivation. Personnel Review, 49(2), 636-652.

[41]. Newman, A., Miao, Q., Hofman, P. S., & Zhu, C. J. (2016). The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(4), 440-455.

[42]. Nie, D., Lämsä, A. M., & Pučėtaitė, R. (2018). Effects of responsible human resource management practices on female employees’ turnover intentions. Business Ethics: A European Review, 27(1), 29-41.

[43]. Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503-545.

[44]. Ong, M., Mayer, D. M., Tost, L. P., & Wellman, N. (2018). When corporate social responsibility motivates employee citizenship behavior: The sensitizing role of task significance. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 144, 44-59.

[45]. Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Muhammad, R. S. (2013). Organizational Culture and Climate. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[46]. Pablo, R., Rodrigo Daniel, & Arenas. (2008). Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 265-283.

[47]. Paré, G., & Tremblay, M. (2007). The influence of high-involvement human resources practices, procedural justice, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors on information technology professionals’ turnover intentions. Group & Organization Management, 32(3), 326-357.

[48]. Rupp, D. E., & Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 211-236.

[49]. Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Lord, R. G., Trevino, L. K., & Peng, A. C. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1053-1078.

[50]. Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1723-1746.

[51]. Shen, J., & Zhang, H. (2019). Socially responsible human resource management and employee support for external CSR: Roles of organizational CSR climate and perceived CSR directed toward employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(3), 875-888.

[52]. Shen, J., & Zhu, C. (2011). Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(15), 3020-3035.

[53]. Subramony, M. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between HRM bundles and firm performance. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 745-768.

[54]. Suganthi, L. (2019). Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. Journal of Cleaner Production, 232(20), 739-750.

[55]. Sun, L., Aryee, S., & Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 558-577.

[56]. Orlitzky, M., & Swanson, D. L. (2006). Socially responsible human resource management: Charting new territory. In J. R. Deckop (Ed.), Human Resource Management Ethics (pp. 3–25). Information Age Publishing.

[57]. Tian, Q., & Robertson, J. L. (2019). How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Business Ethics, 155(2), 399-412.

[58]. Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137-1148.

[59]. Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990-1017.

[60]. Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Misati, E. (2017). Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. Journal of Business Research, 72(3), 14-23.

[61]. Wright, P. M., Gardner, T. M., Moynihan, L. M., & Allen, M. R. (2005). The relationship between HR practices and firm performance: Examining causal order. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 409-446.

[62]. Youndt, M. A., Subramaniam, M., & Snell, S. A. (2004). Intellectual capital profiles: An examination of investments and returns. Journal of Management Studies, 41(2), 335-361.

[63]. Zhang, Z., Wang, J., & Jia, M. (2022). Multilevel examination of how and when socially responsible human resource management improves the well-being of employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 176(1), 55-71.

[64]. Zhao, H., Chen, Y., & Liu, W. (2023). Socially responsible human resource management and employee moral voice: Based on the self-determination theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(3), 929-946.

[65]. Zhao, H., Zhou, Q., He, P., & Jiang, C. (2021). How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 371-385.

[66]. Fan, H., & Zhou, Z. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee autonomous behavior: A perspective based on social learning theory. Management Review, 30(9), 164-173.

[67]. Fang, Y. (2019). The impact of inclusive human resource management practices on employee innovation behavior: The mediating role of innovation self-efficacy. Science Research Management, 40(12), 312-322.

[68]. Ma, L., Chen, X., & Zhao, S. (2018). A review and outlook of research on corporate social responsibility in organizational behavior and human resource management. Foreign Economics & Management, 40(6), 59-72.

[69]. Wang, J., Zhang, Z., & Jia, M. (2019). Social responsibility-based human resource management practices and counterproductive behavior: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Industrial Engineering/Engineering Management, 33(4), 19-27.

[70]. Yan, A., & Li, G. (2016). A cross-level analysis of the impact of corporate social responsibility on employee behavior: The mediating role of external honor and organizational support. Management Review, 28(1), 121-129.

[71]. Zhao, H., & Zhou, Q. (2018). A review and outlook of research on socially responsible human resource management. China Human Resources Development, 35(7), 31-42.

Cite this article

Guo,H.;Yan,A.;Chen,S. (2024). A Study on the Mechanism of Corporate Social Responsibility-Oriented Human Resource Management’s Impact on Employees’ CSR-Specific Performance. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies,13,77-88.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Afsar, B., Al-Ghazali, B. M., Rehman, Z. U., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). The moderating effects of employee corporate social responsibility motive attributions (substantive and symbolic) between corporate social responsibility perceptions and voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 769-785.

[2]. Alexander, D., & Stajkovic, A. (2006). Development of a core confidence-higher order construct. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1208-1224.

[3]. Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., et al. (2000). Manufacturing Advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

[4]. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

[5]. Bendell, B. L. (2017). I don’t want to be green: Prosocial motivation effects on firm environmental innovation rejection decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(2), 277-288.

[6]. Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2006). Identity, identification, and relationship through social alliances. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 128-137.

[7]. Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder-company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 257-272.

[8]. Blumberg, M., & Pringle, C. D. (1982). The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Academy of Management Review, 7(4), 560-569.

[9]. Bos Nehles, A. C., Van Riemsdijk, M. J., & Kees Looise, J. (2013). Employee perceptions of line management performance: Applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 861-877.

[10]. Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203-221.

[11]. Bradley, P. O., Kai, C. Y., Jeffrey, S. B., Jianghua, M., & David, W. H. (2018). The impact of leader moral humility on follower moral self-efficacy and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 146-163.

[12]. Burke, M. J., Borucki, C. C., & Hurley, A. E. (1992). Reconceptualizing psychological climate in a retail service environment: A multiple-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(5), 717-729.

[13]. Cao, Y., Pil, F. K., & Lawson, B. (2021). Signaling and social influence: The impact of corporate volunteer programs. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(2), 183-196.

[14]. Ciocirlan, C. E. (2017). Environmental workplace behaviors: Definition matters. Organization & Environment, 30(1), 51-70.

[15]. Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(1), 19-33.

[16]. Crilly, D., Schneider, S. C., & Zollo, M. (2008). Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior. European Management Review, 5(3), 175-190.

[17]. De Roeck, K., & Maon, F. (2016). Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 609-625.

[18]. Ellis, A. D. (2009). The impact of corporate social responsibility on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2009, No. 1, pp. 1-6). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

[19]. Finkelstein, M. A., Penner, L. A., & Brannick, M. T. (2005). Motive role identity, and prosocial personality as predictors of volunteer activity. Social Behavior & Personality, 33(4), 403-418.

[20]. Gelade, G., & Ivery, M. (2003). The impact of human resource management and work climate on organizational climate. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 383-404.

[21]. Gjølberg, M. (2009). Measuring the immeasurable?: Constructing an index of CSR practices and CSR performance in 20 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1), 10-22.

[22]. Gond, J. P., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 225-246.

[23]. Grant, A., & Adam, M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48-58.

[24]. Grant, A., & Berg, J. (2011). Prosocial Motivation at Work: When, Why, and How Making a Difference Makes a Difference. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[25]. Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 663-685.

[26]. Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2014). Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(2), 277-279.

[27]. Hannah, S. T., & Avolio, B. J. (2010). Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research, 62(4), 291-310.

[28]. Jiang, K., Chuang, C. H., & Chiao, Y. C. (2015). Developing collective customer knowledge and service climate: The interaction between service-oriented high-performance work systems and service leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1089-1106.

[29]. Kim, C. H., & Scullion, H. (2013). The effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on employee motivation: A cross-national study. Poznan University of Economics Review, 13(2), 5-30.

[30]. Kundu, S. C., & Gahlawat, N. (2015). Socially responsible HR practices and employees’ intention to quit: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Human Resource Development International, 18(4), 387-406.

[31]. Lee, B. Y., Kim, T. Y., Kim, S., Liu, Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). Socially responsible human resource management and employee performance: The roles of perceived external prestige and employee human resource attributions. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(4), 828-845.

[32]. Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47-57.

[33]. Lee, H. W., Pak, J., Kim, S., & Li, L. (2016). Effects of human resource management systems on employee proactivity and group innovation. Journal of Management, 45(2), 819-846.

[34]. Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y., & Harden, E. E. (2006). A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Research in Personnel & Human Resources Management, 25(6), 217-271.

[35]. Lin, Y. T., Liu, N. C., & Lin, J. W. (2022). Firms’ adoption of CSR initiatives and employees’ organizational commitment: Organizational CSR climate and employees’ CSR-induced attributions as mediators. Journal of Business Research, 140, 626-637.

[36]. Manika, D., Wells, V. K., Gregory-Smith, D., & Gentry, M. (2015). The impact of individual attitudinal and organisational variables on workplace environmentally friendly behaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(4), 663-684.

[37]. Meijerink, J. G., & Nehles, A. C. (2018). The effect of Strength-Based Talent Management on employee performance: The impact of employees’ ability, motivation and opportunity to perform. University of Twente.

[38]. Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 805-824.

[39]. Mossholder, K. W., Richardson, H. A., & Settoon, R. P. (2011). Human resource management systems and helping in organizations: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 33-52.

[40]. Nathan, E., Alexander, N., Abby, J. Z., & Steven, S. Z. (2019). The relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ internal and external community citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of prosocial motivation. Personnel Review, 49(2), 636-652.

[41]. Newman, A., Miao, Q., Hofman, P. S., & Zhu, C. J. (2016). The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(4), 440-455.

[42]. Nie, D., Lämsä, A. M., & Pučėtaitė, R. (2018). Effects of responsible human resource management practices on female employees’ turnover intentions. Business Ethics: A European Review, 27(1), 29-41.

[43]. Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503-545.

[44]. Ong, M., Mayer, D. M., Tost, L. P., & Wellman, N. (2018). When corporate social responsibility motivates employee citizenship behavior: The sensitizing role of task significance. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 144, 44-59.

[45]. Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Muhammad, R. S. (2013). Organizational Culture and Climate. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[46]. Pablo, R., Rodrigo Daniel, & Arenas. (2008). Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 265-283.

[47]. Paré, G., & Tremblay, M. (2007). The influence of high-involvement human resources practices, procedural justice, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors on information technology professionals’ turnover intentions. Group & Organization Management, 32(3), 326-357.

[48]. Rupp, D. E., & Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 211-236.

[49]. Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Lord, R. G., Trevino, L. K., & Peng, A. C. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1053-1078.

[50]. Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1723-1746.

[51]. Shen, J., & Zhang, H. (2019). Socially responsible human resource management and employee support for external CSR: Roles of organizational CSR climate and perceived CSR directed toward employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(3), 875-888.

[52]. Shen, J., & Zhu, C. (2011). Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(15), 3020-3035.

[53]. Subramony, M. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between HRM bundles and firm performance. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 745-768.

[54]. Suganthi, L. (2019). Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. Journal of Cleaner Production, 232(20), 739-750.

[55]. Sun, L., Aryee, S., & Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 558-577.

[56]. Orlitzky, M., & Swanson, D. L. (2006). Socially responsible human resource management: Charting new territory. In J. R. Deckop (Ed.), Human Resource Management Ethics (pp. 3–25). Information Age Publishing.

[57]. Tian, Q., & Robertson, J. L. (2019). How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Business Ethics, 155(2), 399-412.

[58]. Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137-1148.

[59]. Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990-1017.

[60]. Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Misati, E. (2017). Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. Journal of Business Research, 72(3), 14-23.

[61]. Wright, P. M., Gardner, T. M., Moynihan, L. M., & Allen, M. R. (2005). The relationship between HR practices and firm performance: Examining causal order. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 409-446.

[62]. Youndt, M. A., Subramaniam, M., & Snell, S. A. (2004). Intellectual capital profiles: An examination of investments and returns. Journal of Management Studies, 41(2), 335-361.

[63]. Zhang, Z., Wang, J., & Jia, M. (2022). Multilevel examination of how and when socially responsible human resource management improves the well-being of employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 176(1), 55-71.

[64]. Zhao, H., Chen, Y., & Liu, W. (2023). Socially responsible human resource management and employee moral voice: Based on the self-determination theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(3), 929-946.

[65]. Zhao, H., Zhou, Q., He, P., & Jiang, C. (2021). How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 371-385.

[66]. Fan, H., & Zhou, Z. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee autonomous behavior: A perspective based on social learning theory. Management Review, 30(9), 164-173.

[67]. Fang, Y. (2019). The impact of inclusive human resource management practices on employee innovation behavior: The mediating role of innovation self-efficacy. Science Research Management, 40(12), 312-322.

[68]. Ma, L., Chen, X., & Zhao, S. (2018). A review and outlook of research on corporate social responsibility in organizational behavior and human resource management. Foreign Economics & Management, 40(6), 59-72.

[69]. Wang, J., Zhang, Z., & Jia, M. (2019). Social responsibility-based human resource management practices and counterproductive behavior: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Industrial Engineering/Engineering Management, 33(4), 19-27.

[70]. Yan, A., & Li, G. (2016). A cross-level analysis of the impact of corporate social responsibility on employee behavior: The mediating role of external honor and organizational support. Management Review, 28(1), 121-129.

[71]. Zhao, H., & Zhou, Q. (2018). A review and outlook of research on socially responsible human resource management. China Human Resources Development, 35(7), 31-42.