1. Introduction

Most countries have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and have fought against it (Cifuentes-Faura, 2022a). In this scenario, the role of business was crucial as an actor to revitalize the economy.

Companies faced a series of strategic and operational risks, such as delays or interruptions in the supply of raw materials; changes in customer demand; rising costs; logistical reductions leading to delays in deliveries; problems in protecting the health and safety of employees or difficulties related to the import and export of products. Companies had to be socially responsible and carry out good corporate governance, ensuring the safety and proper organization of all employees.

Teleworking has been largely imposed on the entire population as a result of COVID-19. This is defined as a new work scheme, in a place far from a central office or production, commercial or service facilities, etc., separating the worker from personal contact with colleagues and leaders who are in that office, plant or commercial area. Telework integrated with technology makes this physical separation possible by facilitating real-time communication with different levels of a company (Joyce et al., 2009; Gálvez et al., 2011; Messenger & Gschwind, 2016; Suh et al., 2017).

On the part of companies, in order to monitor people working outside their physical place, it is necessary to think of new concepts for the management of organizations and their staff, such as in the field of human management, monitoring working hours, inclusion in promotion programmes, monitoring in welfare programmes, etc., or in the field of occupational safety and health, with monitoring of workstations and training, psychosocial risk, ergonomic risks. Teleworking is also contributing to reducing environmental pollution (Kim, 2016). In the situation caused by COVID-19, many companies, especially the small enterprises that are most affected, needed to reinvent themselves, to make the most of work and to seek new strategies to reactivate their businesses.

2. Importance of Telework

Telework has great positive aspects for worker health:

•Workers who have household responsibilities can manage their time to fulfil them (Fan Ng; 2010), such as caring for small children, caring for sick people or the elderly, among others (Salazar-Solís, 2016).

•Favourable working environments can be created, which would increase worker satisfaction. (Eddelston & Mulki, 2017; Virick et al., 2010)

•It reduces the stress and complications for the worker of moving from home to work and vice versa. (Mann & Holdsworth; 2003; Morganson et al., 2010, Wicks, 2002)

•Time spent on transport from home to work and vice versa can be used for other personal activities (Leung & Zhang, 2017)

•It should be implemented as a humane management strategy in pursuit of worker welfare (Ilozor et al., 2001), not just sending the person home with a computer.

Several papers have reflected the importance of teleworking in reducing environmental pollution and contributing to sustainability. Kim (2016) conducted a study for the population of Seoul where he determined that teleworking reduces congestion by making workers travel fewer kilometres. He also argues that for teleworking to be effective in reducing congestion, it must be accompanied by other environmental policies.

Pérez et al. (2004) found that for every day of teleworking, it is estimated that 62 grams of nitrogen oxide, 581 grams of carbon monoxide and 70.2 grams of solid particles are reduced. Carnicer et al. (2003) found an average reduction of 65% of kilometres per day if teleworking is carried out.

On the other hand, during teleworking the pressure at work is usually less. This is determined by several studies such as Vesala and Tuomivaara, (2015), which showed that pressure at work was significantly lower during the teleworking day compared to the initial situation. The experience of having negative feelings during work was low and stress was also low.

3. Teleworking During COVID-19

Teleworking has become a major part of our lives. In the business world this idea is only conceived during the pandemic. However, the return to face-to-face activity also indicates the need for changes to adapt to the new normality. Millions of people have worked from home during the pandemic, and many still do so for safety.

Telework is not regulated at the European Union (EU) level through legal mechanisms. The EU directive 2019/1152 on transparent and predictable working conditions addressed some of the challenges protecting remote telecommuters. This directive requires workplace provisions to be put in place and working patterns to be clarified in the employment contract, so as to achieve a positive impact on work-life balance.

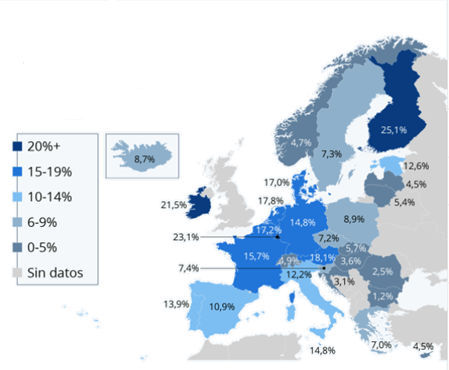

In the following graph (Figure 1), the percentage of people who routinely teleworked in 2020 is shown. Finland, Luxembourg and Ireland stand out.

Figure 1. Percentage of people who regularly teleworked in 2020. (Source: Eurostat)

In Europe, the growth of telework during the pandemic has been exponential. Figure 2 shows the evolution of telework data in European countries over the last decade. It shows the percentage of workers who usually use telework.

Finland was in 2020 the country with the highest percentage of people teleworking (25.1%) experiencing a growth of 11 percentage points, going from 14.1% in 2019 to 25.1% in 2020. It is followed by Luxembourg at 23.1% and Ireland at 21.5%, which was one of the countries experiencing the largest growth in telework from 2019 to 2020, marked by the Covid-19 pandemic. Telework also increased considerably in percentage points over 2019 in countries such as Greece and Italy (+239%), although their telework rates are quite a bit lower, being 7% and 12.2% in 2020, respectively. In 2019, Greece had just 1.9% of people teleworking on a regular basis and Italy 3.6%. Figure 3 shows the variations in telework during the year 2020 marked by the pandemic compared to the previous year.

If gender is taken into account, three groups of countries can be distinguished. A first group formed by those countries where there are hardly any differences between men and women, such as Portugal or Luxembourg, a fairly large group of countries where the variation experienced by women was much higher than that of men, such as Greece, Italy or Bulgaria, and a minority group of countries where the variation experienced by men was slightly higher than that of women, such as France or Germany.

Figure 2. Percentage of workers who usually use telework as a priority. (Source: Own elaboration based on Eurostat database.)

Figure 3. Variations experienced in European countries in 2020 with respect to 2019 in telework.

(Source: own elaboration.)

Having presented the data and the variations experienced by telework, the following section offers possible measures that companies can adopt due to the new situation caused by the pandemic.

4. Possible Measures to Be Taken for Success in the Company Due to Emergencies Such US COVID-19

To ensure the success of business continuity and the management of events such as Covid-19, we recommend that companies implement and maintain the following measures:

Establish Emergency Decision-Making Teams.

This team should ensure that decisions are made quickly and effectively in the face of the pandemic. It should also set out the objectives to be achieved during the Covid-19 emergency business plan and assess the strengths and weaknesses of the company and its workers.

Assess Risks and Establish Emergency Response Mechanisms.

Sustainable contingency plans should be established for emergencies. If a company does not have such a plan, they should conduct a comprehensive assessment of all risks immediately, looking at the company's human capital, supply chain or customers.

The company should be able to respond to risks related to office space, logistics, production plans, procurement, material supply, staff security or financial capital.

Create Clear and Standardised Communication Documents for Employees, Customers and Suppliers.

Fluid and effective communication with employees and external parties is necessary. In addition, customer service must be strengthened to provide a good image and maintain standards of quality and commitment to the customer.

In addition, the information system implemented in the company must make it possible to gather effective information and transmit it to employees and external personnel.

Taking Care of the Health of Employees, Worrying about Their Physical and Mental Well-being.

The company should establish a system for monitoring employee health and maintaining personal information on employee health with full guarantees of confidentiality (Konradt et al., 2009; Paridon & Hupke; 2009).

The company must organize training talks for its employees to teach them about safety measures in the face of the pandemic. It is important to protect employees and increase awareness of the need to prevent risks.

Focus on Response Plans for Risks Generated in the Supply Chain.

In managing inventories, companies should take into account factors such as blockage of consumption, the corresponding increase in financial costs and pressure on cash flow.

Organizations with a long production cycle should prepare in advance for a consumption peak when production increases to avoid the risk of insufficient stocks.

Develop Solutions to Ensure Compliance and Maintain Customer Relationships If Production Cannot Be Resumed in the Short Term under the Same Conditions.

After a health emergency situation, organisations should work closely with customers to understand the changes in the market and understand the impact of resuming activity.

In addition, it is important to thoroughly analyse contracts, as due to the exceptional causes and laws issued during the crisis period, breaches of contract may not have legal consequences.

Companies should identify and evaluate contracts whose performance may be affected and notify customers, in order to mitigate possible losses, as well as to assess whether it is necessary to sign a new contract or additional clauses. It is important to generate and retain all documentary evidence to be used in possible civil claims.

Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development Strategies in Decision Making.

The publication of adequate corporate information on the crisis can improve a company's public image.

It is necessary to be able to apply corporate social responsibility from the perspectives of the environment, society, the economy and the stability of employees, as well as to coordinate relations with the community and supply companies. The potential impact and duration of the epidemic must be assessed, plans adjusted and, in the case of shareholders or the board of directors, proposed measures and results communicated.

Develop A Plan for Managing Employee Data, Information Security and Privacy.

Companies should establish mechanisms to manage employee data and register internal and external staff, suppliers and other employees with whom the organisation has contact.

Information security emergency response plans should also be developed to ensure information security and stability of operations. Protocols must be in place to ensure the operation of networks, systems and applications.

It is also essential to protect the personal and data privacy of both customers and employees.

Companies Should Consider Adjusting Their Budgets and Implementation Plans.

Special attention should be paid to cash flow, to ensure the security of funds, in accordance with the pace of suppliers and the work plans of employees.

In addition, the situation of international import and export trade should be monitored closely, particularly sudden changes or possible impacts on the places of origin of major products, which could result in considerable losses to the enterprise itself. To avoid such incidents, companies should establish different scenarios that include the responses that would be carried out in these situations, such as contingency plans for basic suppliers, alternative suppliers and consideration of other means of transport.

From an economic and business point of view, this crisis must be an opportunity to change the way business is managed, so that it becomes more efficient and competitive. This crisis must be a turning point to learn from the mistakes of the past. This extraordinary situation must become a new opportunity to demand that both companies act in accordance with the principles of sustainable development (Wagner, 2010; Zamagni, 2013; Ciocoiu, 2011; Câmara, 2014; Biswas and Roi, 2015). Without a doubt, the new order we build after the pandemic must be focused on sustainability.

5. Conclusions

It is important to be informed in order to know the real situation and the plans drawn up by public institutions, and to rely on truthful information, away from the bullshit. In addition, the individual situation of each company must be defined and not be led by the actions of third parties or those decisions that are fashionable because they are generalised.

We must know how to look for where we can continue to be competitive, there will be sectors of activity that are literally in a state of total hibernation, therefore, either new business opportunities are sought or the impact must be quantified in order to take drastic measures in companies, especially in small enterprises. It is necessary and of vital importance, to generate scenarios spatially in this area, so that we can reach the dimension of the impact and correct it according to each temporary situation.

What must not be forgotten in a company is that people come first. We must never put workers' health at risk, contemplating those measures that are necessary to safeguard their well-being. Following the advice and recommendations of the health authorities is an obligation, not an option. Transmitting calm is the principle for actions and plans to be properly executed.

It is important to make a daily review of the actions implemented and equipment for monitoring. Making decisions based on collective intelligence will help make them more robust. It is necessary to adapt quickly, so do not be afraid to modify the planned strategy as many times as necessary in this contingency situation.

In this work, it has been exposed through the presentation of data, the importance of telework. It should try to regulate globally a telework law that regulates the rights and duties of workers, and that allows the company and the workers themselves to be as productive as possible and get the best performance.

This crisis was an opportunity to change those habits that harm the progress and development of citizens and the planet. Furthermore, this pandemic has led to an increase in citizen solidarity, so the population will give even more importance to those companies that are socially responsible. In this sense, companies that are committed to sustainable development are likely to benefit from the good brand image that this will generate (Cifuentes-Faura, 2021, 2022b).

The pandemic has served to make companies stronger, to look for new adaptation measures, and to improve workers' conditions, for example, with greater flexibility or teleworking. All measures adapted during the pandemic period should be maintained in the company in the long term.

References

[1]. Biswas, A. & Roy, M. (2015). Green products: an exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. Journal of Cleaner Production, 87, 463-468.

[2]. Câmara, J. B. D. (2014). Reflections on the Green Economy (Redemption of the Principles of Mill and Pigou): A View of a Brazilian Environmentalist. Journal of Environmental Protection, 5(12), 1153.

[3]. Carnicer, M.P., Jiménez, M. J., Sánchez, A., Pérez, M. (2003). Análisis del impacto del teletrabajo en el medioambiente urbano. España. Boletín Económico del ICE (23 – 39)

[4]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2021). COVID-19 and the opportunity to create a sustainable world through economic and political decisions. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 18(4), 417-421.

[5]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022a). Analysis of containment measures and economic policies arising from COVID-19 in the European Union. In The Political Economy of Covid-19 (pp. 134-147). Routledge.

[6]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022b). Circular economy and sustainability as a basis for economic recovery post-COVID-19. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2(1), 1-7.

[7]. Ciocoiu, C. N. (2011). Integrating digital economy and green economy: opportunities for sustainable development. Theoretical and Empirical Researches. Urban Management, 6(1), 33.

[8]. Eddleston, K. A., & Mulki, J. (2017). Toward Understanding Remote Workers’ Management of Work–Family Boundaries: The Complexity of Workplace Embeddedness. Group & Organization Management, 42(3), 346-387.

[9]. Fan Ng, C. (2010). Teleworker's home office: an extension of corporate office? United Kingdom. Facilities, 28(3/4), 137-155.

[10]. Gálvez, A., Martínez, M. J., & Pérez, C. (2011). Telework and work-life balance: Some dimensions for organisational change. Journal of Workplace Rights, 16(3-4).

[11]. Ilozor, D. B., Ilozor, B. D., & Carr, J. (2001). Management communication strategies determine job satisfaction in telecommuting. United Kingdom. Journal of management development, 20(6), 495- 507.

[12]. Joyce, K., Pabayo, R., Critchley, J. A., & Bambra, C. (2009). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. United Kingdom, 2.

[13]. Kim, S. N. (2016). Two traditional questions on the relationships between telecommuting, job and residential location, and household travel: revisited using a path analysis. The Annals of Regional Science, 56(2), 537-563

[14]. [Konradt, U., Schmook, R., Wilm, A., & Hertel, G. (2000). Health circles for teleworkers: selective results on stress, strain and coping styles. United Kingdom. Health education research, 15(3), 327-338.

[15]. [Leung, L., & Zhang, R. (2017). Mapping ICT use at home and telecommuting practices: A perspective from work/family border theory. United Kingdom. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 385-396.

[16]. [Mann, S., & Holdsworth, L. (2003). The psychological impact of teleworking: stress, emotions and health. Estados Unidos. New Technology, Work and Employment, 18(3), 196.

[17]. Messenger, J. C., & Gschwind, L. (2016). Three generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R) evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. New Technology, Work and Employment, 31(3), 195-208.

[18]. Morganson, V. J., Major, D. A., Oborn, K. L., Verive, J. M., & Heelan, M. P. (2010). Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: Differences in work-life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. United Kingdom. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(6), 578-595.

[19]. Paridon, H. M., & Hupke, M. (2009). Psychosocial impact of mobile telework: Results from an online survey. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 5(1).

[20]. Pérez, M. P., Sánchez, A. M., Carnicer, M. P. D. L., & Jiménez, M. J. V. (2004). The environmental impacts of teleworking: A model of urban analysis and a case study. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 15(6), 656-671.

[21]. Salazar-Solís, M. (2016). Telework: conditions that have a positive and negative impact on the work-family conflict. United Kingdom. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 29(4), 435-449. 46.

[22]. Suh, A., Suh, A., Lee, J., & Lee, J. (2017). Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Inglaterra. Internet Research, 27(1), 140-159.

[23]. Vesala, H., & Tuomivaara, S. (2015). Slowing work down by teleworking periodically in rural settings? Personnel Review, 44(4), 511-528.

[24]. Virick, M., DaSilva, N., & Arrington, K. (2010). Moderators of the curvilinear relation between extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. California. Human Relations, 63(1), 137-154

[25]. Wagner, M. (2010). The role of corporate sustainability performance for economic performance: a firm-level analysis of moderation effects. Ecological Economics, 69, 1553-1560

[26]. Wicks, D. (2002). Successfully increasing technological control through minimizing workplace resistance: understanding the willingness to telework. United Kingdom. Management Decision, 40(7), 672-681.

[27]. Zamagni, S. (2013). Por una economía del bien común. Buenos Aires, Ciudad Nueva, 334.

Cite this article

Cifuentes-Faura,J. (2023). The Impact of the COVID-19 on Business Companies: Measures and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies,1,12-20.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Biswas, A. & Roy, M. (2015). Green products: an exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. Journal of Cleaner Production, 87, 463-468.

[2]. Câmara, J. B. D. (2014). Reflections on the Green Economy (Redemption of the Principles of Mill and Pigou): A View of a Brazilian Environmentalist. Journal of Environmental Protection, 5(12), 1153.

[3]. Carnicer, M.P., Jiménez, M. J., Sánchez, A., Pérez, M. (2003). Análisis del impacto del teletrabajo en el medioambiente urbano. España. Boletín Económico del ICE (23 – 39)

[4]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2021). COVID-19 and the opportunity to create a sustainable world through economic and political decisions. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 18(4), 417-421.

[5]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022a). Analysis of containment measures and economic policies arising from COVID-19 in the European Union. In The Political Economy of Covid-19 (pp. 134-147). Routledge.

[6]. Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022b). Circular economy and sustainability as a basis for economic recovery post-COVID-19. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2(1), 1-7.

[7]. Ciocoiu, C. N. (2011). Integrating digital economy and green economy: opportunities for sustainable development. Theoretical and Empirical Researches. Urban Management, 6(1), 33.

[8]. Eddleston, K. A., & Mulki, J. (2017). Toward Understanding Remote Workers’ Management of Work–Family Boundaries: The Complexity of Workplace Embeddedness. Group & Organization Management, 42(3), 346-387.

[9]. Fan Ng, C. (2010). Teleworker's home office: an extension of corporate office? United Kingdom. Facilities, 28(3/4), 137-155.

[10]. Gálvez, A., Martínez, M. J., & Pérez, C. (2011). Telework and work-life balance: Some dimensions for organisational change. Journal of Workplace Rights, 16(3-4).

[11]. Ilozor, D. B., Ilozor, B. D., & Carr, J. (2001). Management communication strategies determine job satisfaction in telecommuting. United Kingdom. Journal of management development, 20(6), 495- 507.

[12]. Joyce, K., Pabayo, R., Critchley, J. A., & Bambra, C. (2009). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. United Kingdom, 2.

[13]. Kim, S. N. (2016). Two traditional questions on the relationships between telecommuting, job and residential location, and household travel: revisited using a path analysis. The Annals of Regional Science, 56(2), 537-563

[14]. [Konradt, U., Schmook, R., Wilm, A., & Hertel, G. (2000). Health circles for teleworkers: selective results on stress, strain and coping styles. United Kingdom. Health education research, 15(3), 327-338.

[15]. [Leung, L., & Zhang, R. (2017). Mapping ICT use at home and telecommuting practices: A perspective from work/family border theory. United Kingdom. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 385-396.

[16]. [Mann, S., & Holdsworth, L. (2003). The psychological impact of teleworking: stress, emotions and health. Estados Unidos. New Technology, Work and Employment, 18(3), 196.

[17]. Messenger, J. C., & Gschwind, L. (2016). Three generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R) evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. New Technology, Work and Employment, 31(3), 195-208.

[18]. Morganson, V. J., Major, D. A., Oborn, K. L., Verive, J. M., & Heelan, M. P. (2010). Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: Differences in work-life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. United Kingdom. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(6), 578-595.

[19]. Paridon, H. M., & Hupke, M. (2009). Psychosocial impact of mobile telework: Results from an online survey. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 5(1).

[20]. Pérez, M. P., Sánchez, A. M., Carnicer, M. P. D. L., & Jiménez, M. J. V. (2004). The environmental impacts of teleworking: A model of urban analysis and a case study. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 15(6), 656-671.

[21]. Salazar-Solís, M. (2016). Telework: conditions that have a positive and negative impact on the work-family conflict. United Kingdom. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 29(4), 435-449. 46.

[22]. Suh, A., Suh, A., Lee, J., & Lee, J. (2017). Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Inglaterra. Internet Research, 27(1), 140-159.

[23]. Vesala, H., & Tuomivaara, S. (2015). Slowing work down by teleworking periodically in rural settings? Personnel Review, 44(4), 511-528.

[24]. Virick, M., DaSilva, N., & Arrington, K. (2010). Moderators of the curvilinear relation between extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. California. Human Relations, 63(1), 137-154

[25]. Wagner, M. (2010). The role of corporate sustainability performance for economic performance: a firm-level analysis of moderation effects. Ecological Economics, 69, 1553-1560

[26]. Wicks, D. (2002). Successfully increasing technological control through minimizing workplace resistance: understanding the willingness to telework. United Kingdom. Management Decision, 40(7), 672-681.

[27]. Zamagni, S. (2013). Por una economía del bien común. Buenos Aires, Ciudad Nueva, 334.