1. Introduction

After the presence of the first photograph, the art started questioning itself. The depiction of reality, or the form of art, has been recreated through every other isms. Once the Brillo Box by Andy Warhol was introduced, the critical problem soon turned to how we identify something as art. Marcel Duchamp was one of the pioneers who contributed to this question through his conceptual art. This revolution struke the art world with a comet named “philosophy”. By then, this transformation seemed to happen during the development of architecture as well. With the massive destruction of World War II, Brutalist style was mainly used to conform to the emergency of the housing shortage. This research has chosen Marcel Duchamp and Brutalism, aiming to bridge a connection between two seemingly unrelated characters that had relaunched their own fields with resemblance of their cognitions. This essay will elaborate on this connection through key statements, which are “thinking over crafting” and “equality and inclusion”.

2. Thinking over crafting

2.1. Duchamp: proposing philosophy

Marcel Duchamp, commonly acknowledged as an artist, also a chess player, and a writer, contributed substantially to the revolutionary development of art.

During the interview with the Philadephia Museum of Art (2020), Duchamp summarized two important constitutions of art pieces: first, whether the art has come up with internal philosophy, rather than the retinal pleasure conveyed through materiality; second, the consecutively avant-garde creation instead of imprisoning oneself with identities what society assigned ones to.

Figure 1: Nu descendant un escalier (N°2) (1913)

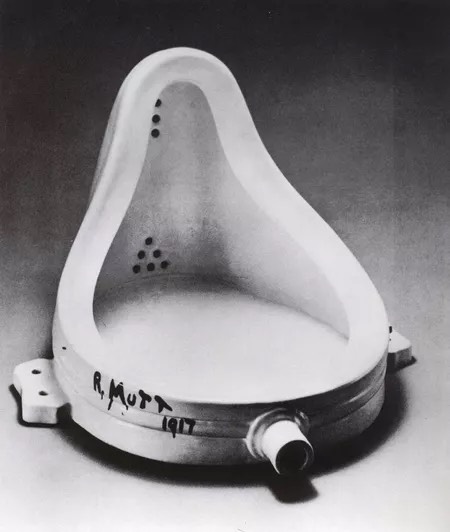

Figure 2: Fountain (1917)

Among the varieties of Marcel Duchamp’s artworks, he built his reputation initially through the Nu descendant un escalier (N°2), well appraised by the American society. This painting has been greatly influenced by cubism but by adding another dimension of time. Though it has a strong resemblance with futurism, Duchamp stated that he did not encounter the futuristic movement until he finished this painting. In other words, the simultaneous invention of appending a timeline was contributed by Duchamp and the futurist artist.

Beyond the strokes on the canvas, Duchamp created the “ready-mades”. Receiving both criticism and appreciation, the Fountain is the most renowned ready-made and explicit representation of the conceptual art.

The Fountain was submitted to the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists anonymously, but was placed in an inconspicuous position where Duchamp could not find it. This urinal with a word trick “R. Mutt” questioned the conventional idea of art and aesthetics. When he was attempting to make objects beyond the scope of art, he constructed a bridge between thinking and making, commented Humble [1].

The conceptual art, including the ready-mades, abandoned the pursuit of retinal pleasure to seek more internalized philosophy presented through the medium of art. (some contemporary conceptual even gave up the physical entities). Duchamp is the undisputed advocate of his own philosophy and also inspired the subsequent artists and the art critics.

The composition of artworks was, but Duchamp was also fascinated with the contingency.

With hidden noise, created in 1916, contains unknown objects added by Walter Arensberg inside the ball of twine, which is suppressed by two copper plates and fixed by four screws. Duchamp himself never figured out what is inside the ball. But every time he shakes it, the sound produced makes him wonder and feel intrigued.

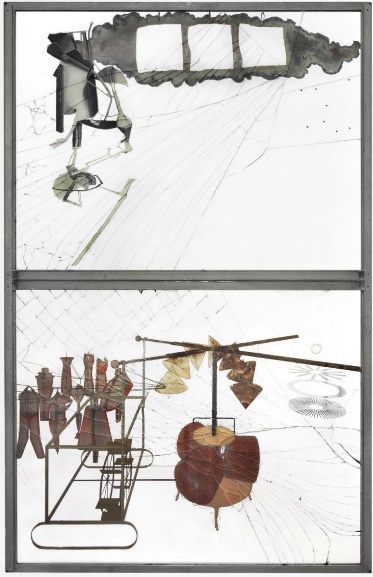

The symmetrical cracks on The Large Glass, or The Bride Stripped By Her Bachelors, Even, were caused by transportation. Duchamp declared the cracks not as flaws, but as improvement. He mentioned in the dialogue with Cabanne that he was giving birth to art after the completion and art shall be seen as a living being instead of being permanent [2]. These cracks may convey a sense of vitality, an ever-changing status of the glass instead of remaining still.

Figure 3: The Hidden Noise (1916)

Figure 4: The Bride Stripped By Her Bachelors, Even (1915 to 1923)

2.2. Brutalism: essential ethics

Reyner Banham defined the term Brutalism in his influential essay with three characteristics: 1. Memorability as an image; 2. Clear exhibition of structure; 3. Valuation of materials "as found”, stating the ethics and the aesthetics are equally important [3]. Nevertheless, the definition of the Brtutalism left space for much controversy and discussions. But the following paragraph would like to infer that the ethical concern is more outstanding instead of the aesthetics. First and foremost, Peter & Alison Smithsons, whose designed construction, the School at Hunstanton, was first referred to as “Brutalist architecture” and themselves referred as “Brutalist architects”, with this Swedish-English term’s definition remained uncertain until the commentaries addressed it to the school [3].

Figure 5: School at Hunstanton (1954)

In a written conversation record on the topic of Brutalism, Peter Smithson suggests what really stands out in the Brutalist style is the ethics that underlies the aesthetics [4].

Throughout this conversation, they criticized the “machine-like environment” for being anti-humane, especially the prevalence of the skyscrapers. The increase of efficiency costs the lack of social and ethical design. They urged the need for architectural designs to correspondingly evolve as the society and the form of labor have been progressed.

Furthermore, one of the fundamental reasons for the boost of Brutalism is the housing shortage after World War II. The majority of the brutalist architecture had taken upon the character to solve this intense social and economic issue. In other words, Brutalism was incubated to be the solution to the housing shortage. This comparatively clear objective shaped the design of the architects substantially to satisfy the needs of society.

Marcel Duchamp and the conceptual art alternatively underline the significance of the philosophy inherited in the art itself shall override the visual pleasure. Brutalism concerns the interaction of community and living philosophy instead of the decorations and design of facades under the instruction of ratio.

They both deny the artisanship of the conventional art or architecture, which were pursuing superficial enjoyment; in contrast, they drew attention to the metaphysical essence and ultimately redirected the entire discipline towards internal wisdom. And their bravery to challenge the authoriative mainstream shall be admired.

3. Equality and inclusion

3.1. Duchamp: the vicious taste

Unlike some of the artists would do, establishing their features and techniques into certain “isms”, Duchamp never constrianed himself with a specified doctrine. Duchamp thought that the concept of taste would form through repetition of conspicuous characteristics. And the taste itself has no contribution to the progress of art.

“There’s no such a thing in the art shall be considered as good taste, or bad taste because this concept of taste is always mutual” [5]. The redundancies from his perspective is to create self-repeating artworks. Duchamp practiced this idea and kept pushing forward the boundaries of art throughout his life. Since the tastes were never significant, a hierarchical judgment is erroneous and a rigid benchmark is meaningless.

With the introduction of the Fountain mentioned above and the Brillo Box by Andy Warhol, they became the testimonies of the theory “the end of art”, proposed by art theorist Arthur C. Danto. According to his theory, after the art has transcended mimesis and emotional expression, the art history entered the epoch named, the “post-historical era”: “finally, it became apparent that there were no stylistic or philosophical constraints” [6].

As we proceeded to this post-historical era, the standard had decomposed. The definition of this post-historical era is the end of “master narrative”. The conflict between the mainstream and other minor styles had come to an end. Individuals are centralized. Post-historical artists hold a more equitable view towards art. This generally was acknowledged as the inclination to the pluralism [7].

3.2. Brutalism: the inclusive community

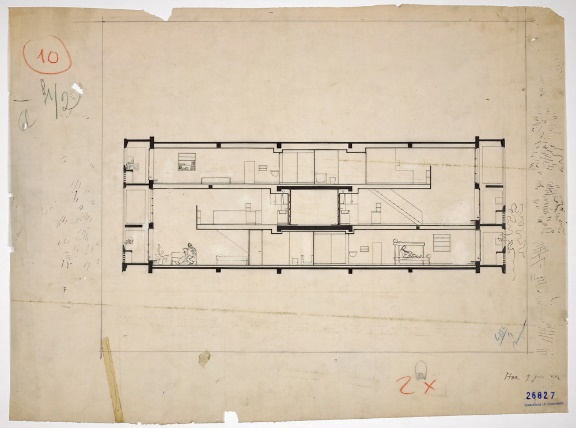

Being the solution to the destruction caused by the war and further scrutinized to compact living, Le Corbusier’s project Unité d’Habitation in Marseille was built aiming to be the prototype of massive housing in the modern era. Millais mentioned that it has presented the sophisticated consideration towards the living philosophy as the solution for overpopulation [4]. The presence of communal space and the idea of inclusive community were emphasized throughout the design. Millais also wrote that the concept of “social condenser”, entitling the space with both public and private attributes, raised by Ginzburg and applied to the Narkomfin building, had affected the Unite from the beginning [8].

Supporting facilities including a hotel, a school, restaurants, and shops are implemented. Most needs of the residents can be fulfilled solely inside this building. The unique L-shaped design increases the efficiency of utilizing the space, providing every resident with access to the corridor while wiping out 2/3 of redundant places. The modulated design showed the impartial consideration and made replication applicable.

Figure 6: Unité d’Habitation (1940s) Figure 7: Sectional plan of the units

“Architectural Principle in the Age of Humanism”, written by Rudolf Wittkower, offered the discipline of architecture with another perspective to analyze architecture in terms of harmonic music ratio and directly contributed to the neo-palladian revival. This revival, with emphasis on form and classical elements, was strongly opposed by Peter & Alison Smithsons, implied in their conversation on Brutalism [4]:

“One puts less value on the thing being symmetrical or cubic and more on the fact that its particular geometry, builds up into a relationship with other geometry not in a Camillo Sitte romantic way, but in a functional way.”

By freeing up the spaces beyond the scopes of ratio, Brutalism does not only hold an antagonist position against the formulaic and classical aesthetics, but also shows a transcending pursuit to the inner loftiness to reconcile inter-personal relationships instead of the superficial beauty.

Brutalism also has an intricate relationship with Communism. In the beginning, a bizarre building in Sweden against the indifferent design was seen as an anomaly against humanism. “Flat roofs, glass, expose of structure,” elements designed by architects Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm received a commentary from their colleague Hans Asplund [3]. Its association with the term “communism” is due to its adversial ideology in contrast to the widely accepted conventions.

Subsequently, after the completion of the project the School at Hunstanton, this term was coined with this construction and started to establish the connections to both materiality and design philosophy. Debate on the definition of this term, then, continued restlessly even until nowadays.

Later, due to its functionality, it prevailed substantially and developed into a unique style in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, which are communist nations. Massive constructions and monuments in the communist nations entailed people with the stereotype of Brutalism to be ruthless, colossal and brutal, like the Bolshaya Tulskaya Residential Complex.

But more fundamentally, the design philosophy somehow aligns with the communist will. Brutalist architecture was born with the hope of creating a shelter for people who suffered from the war. With modulated dwellings, replicating facades, and interior communal spaces the building elaborates its unbiased inclusion and equality.

Figure 8: Bolshaya Tulskaya residential complex (1986)

Pointing out the uselessness and reflecting detestation to the taste, Duchamp and his art works lead the world to embrace the post-historical era. The judgemental and gradable system is outcompeted has transformed to be free and open to various genres of art. The critics are welcome to offer diverse decoding to a particular artwork. Brutalism strengthens the equality and integration of people with different backgrounds and identities, imagining to propose a utopian community where residents are proactively interacting instead of isolating themselves; the design planning aligns with the Communist maxim to bring equality to everyone in the society.

They both introduce an unbiased and welcoming environment, to a certain discipline and to certain groups of people, respectively. This inclusive atmosphere also gives rise to the non-linear development of art and architecture where you can see the coexistence of traditional ones and avant-garde ones nowadays.

4. Conclusion

Based on our inference so far, the artistic concept of Duchamp and the design methodology of Brutalism have resemblance in philosophy and equality. Further research could be done towards the contemporary development of art and architecture to achieve a more comprehensive analysis. However, we can observe this radical change in motif explicitly. The aesthetics means no longer the visual pleasure which is superficial, but the thoughts and morality beneath the materiality. These ideas are both protagonistic to personal narratives. In art, the competition to justify oneself, pursuing the love of the majority in society to become the mainstream, has ended. In architecture, everyone was treated without partiality. People are encouraged to convey this benign relationship when interacting and communicating with others free from bias.

References

[1]. Humble, P. N. (1982). DUCHAMP’S READYMADES: ART AND ANTI-ART. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 22(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaesthetics/22.1.52

[2]. Cabanne, P., & Duchamp, M. (1971). Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA19295887

[3]. Banham, R. (2011). The new brutalism. October, 136, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00034

[4]. Smithson, A., Smithson, P., Drew, J. B., & Fry, E. M. (2011). Conversation on brutalism. October, 136, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00039

[5]. Manufacturing Intellect. (2020, March 13). Marcel Duchamp interview on Art and Dada (1956). (n.d.). [Video]. Youtube. https://youtube.com/watch?v=Wuf_GHmjxLM&t=890s

[6]. Danto, A. C. (2021). After the end of art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated Edition. Princeton University Press.

[7]. Danto, A. C. (2013). What art is. Yale University Press.

[8]. Millais, M. (2015). A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND INFLUENCE OF THE UNITÉ D’HABITATION, MARSEILLES, FRANCE. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 39(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.3846/20297955.2015.1062636

Cite this article

Chen,Z. (2025). Rethinking Aesthetics: The Philosophy and Equality in Duchamp and Brutalism. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,92,23-29.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Humble, P. N. (1982). DUCHAMP’S READYMADES: ART AND ANTI-ART. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 22(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaesthetics/22.1.52

[2]. Cabanne, P., & Duchamp, M. (1971). Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA19295887

[3]. Banham, R. (2011). The new brutalism. October, 136, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00034

[4]. Smithson, A., Smithson, P., Drew, J. B., & Fry, E. M. (2011). Conversation on brutalism. October, 136, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00039

[5]. Manufacturing Intellect. (2020, March 13). Marcel Duchamp interview on Art and Dada (1956). (n.d.). [Video]. Youtube. https://youtube.com/watch?v=Wuf_GHmjxLM&t=890s

[6]. Danto, A. C. (2021). After the end of art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated Edition. Princeton University Press.

[7]. Danto, A. C. (2013). What art is. Yale University Press.

[8]. Millais, M. (2015). A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND INFLUENCE OF THE UNITÉ D’HABITATION, MARSEILLES, FRANCE. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 39(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.3846/20297955.2015.1062636