1. Introduction and hypotheses

Globally, women remain underrepresented in legislatures, holding only about 27% of parliamentary seats as of 2024 [1]. Legislative Council of Hong Kong, China (LegCo) is no exception: female members comprised roughly 15–20% of LegCo in recent years. This deficit in descriptive representation has prompted debate on its consequences for substantive representation of women’s interests. In theory, increasing the number of female legislators should bring greater attention to “women’s issues” such as welfare, health care, education, and gender equality. Scholars have argued that the presence of women in government leads to better representation of women’s preferences and needs [2]. Empirically, many studies have found that female legislators prioritize social policy areas more than their male counterparts [3]. For example, women in various countries tend to focus on health, education, family, and welfare issues, whereas men devote more attention to economics, finance, and defense. These patterns have been observed in both western and non-western contexts, from the United States to Latin America [4]. In terms of legislative behavior, research also suggests that female lawmakers may approach their roles differently, often being more collaborative and responsive to constituents.

One important oversight activity is the posing of parliamentary questions. In venues like the UK House of Commons and the Scottish Parliament, women lawmakers have been shown to act as “women’s interest advocates” by asking questions on topics such as childcare, domestic violence, and gender equality far more frequently than men [5]. Female MPs deliberately introduce a women’s perspective into parliamentary discourse. On the other hand, as female representation increases, some male legislators also begin to address women-centric issues – a phenomenon of male “surrogate representation” observed in the European Parliament [6]. Prior research on Hong Kong, China’s legislature found only minimal gender differences up to 2016. Tam reported limited evidence that Hong Kong, China’s female legislators behaved differently from males in representing women’s interests [7]. Notably, however, the few questions about women’s rights or gender equality in that period were almost exclusively raised by female LegCo members. This suggests that even when greatly outnumbered, women lawmakers bore a disproportionate responsibility for raising women’s concerns.

Against this backdrop, this study asks whether female legislators in Hong Kong, China, differ systematically from male legislators in their questioning behavior. This research focus on four key dimensions and formulate the following hypotheses:

1.Question Format (H1): Female LegCo members are more likely to use oral questions (raised on the floor during sessions) rather than written questions. Because oral questions are addressed in the live chamber with media coverage, female legislators may favor this format to increase their public visibility and amplify their issues, thereby counteracting their numerical minority.

2.Policy Domain Focus (H2): Female members’ questions are more concentrated on social and community welfare issues (e.g. public health, education, social services), and relatively less on traditionally “masculine” domains such as finance, economy, and infrastructure. This expectation follows the common pattern that women politicians emphasize “care” or welfare issues in line with their voter base and gender role expectations. In Hong Kong, China, this research anticipate women will prioritize health, community development, and family policies, whereas men will focus more on economic development, transportation, and security.

3.Gender-Related Topics (H3): Female legislators are more likely to raise issues of gender equality and women’s rights in their questions. For example, women are expected to ask about the status of women, gender discrimination, support for caregivers, or anti-domestic violence measures more often than men. This reflects female legislators serving as substantive representatives for women in the legislature.

4.Breadth of Issues (H4): Female legislators’ questions cover a broader range of policy areas, indicating greater issue diversity. Contrary to the stereotype that women only concern themselves with a narrow set of “female” issues, this research hypothesize that Hong Kong, China’s female LegCo members engage with at least as wide a spectrum of topics as men, if not wider. One rationale is that as a small minority, women lawmakers may deliberately avoid being pigeonholed as niche players, and instead demonstrate competence across multiple domains. By pursuing a broad issue agenda, they seek to enhance their influence and counter marginalization.

By testing these hypotheses, this research aim to present a comprehensive picture of gender-based differences in LegCo of Hong Kong in China questioning behavior and to explore the underlying causes and implications of these differences. LegCo’s hybrid political context and historically low female representation provide a unique case to examine whether patterns noted in other democracies hold under semi-authoritarian conditions. The findings will enrich our understanding of gender and legislative oversight and inform efforts to strengthen women’s voices in politics.

2. Methodology

Data and Sample: This research compiled an original dataset of all questions raised by LegCo members from November 1, 2016 to July 31, 2025, covering multiple legislative sessions and major socio-political changes in Hong Kong, China, during this period. The dataset contains 5,402 parliamentary questions, each linked with the asking legislator and detailed question content. In LegCo, questions can be posed in two formats: oral questions, asked by legislators on the floor during Q&A sessions (with government officials responding on the spot, often folloThis researchd by brief debate), and written questions, which are submitted in writing and receive written replies without floor discussion. Both types serve as oversight tools and include a legislator-crafted question title (summarizing the issue) along with metadata such as the asker’s name and date. In our sample, about 22.9% of questions are oral, indicating that while written queries are more common, oral questions constitute a substantial portion of oversight activity.

This research coded the gender of each asking legislator as female (=1) or male (=0). Across the 2016–2025 period, female legislators initiated approximately 19.3% of all questions. This share is in line with women’s seat share (which averaged around 15–20%), suggesting that as a group, women were as actively engaged in questioning as their numbers would predict. In other words, women legislators were neither notably silent nor excessively talkative relative to men in terms of quantity of questions.

Question Classification: To analyze the content of questions, this research adopted a scalable coding strategy combining a large language model (LLM) and machine learning. First, this research manually and semi-automatically labeled a subset of questions on three key attributes: (a) the question’s policy domain (e.g. health, education, finance, transportation, security, etc.), (b) the frame or perspective used (e.g. a rights-based frame, economic frame, safety frame, or administrative/technical frame), and (c) whether the question is related to gender (explicitly concerning women’s status, gender equality, or women-centric issues). This research employed a Chinese LLM (Qwen-3) to assist in reading question texts and assigning preliminary labels, especially for subtle judgments such as whether a question implicitly involves gender equality. These initial labels were then used to train machine learning classifiers. In particular, this paper extracted TF-IDF text features from the question titles and descriptions, and trained logistic regression models to predict the labels for the remaining 60%+ of questions that had not been human-reviewed. This approach proved effective: the multiclass logistic model for policy domain achieved about 85% accuracy on a validation set, and the binary classifier for gender-related topics reached an F1 score of approximately 0.8, indicating good precision and recall. This research performed spot checks on cases where the model was uncertain (scores near decision thresholds) and adjusted labels as needed to correct any systematic errors. This semi-automated coding yielded a full dataset with each question categorized into one of 11 policy domains (covering the breadth of Hong Kong public policy issues) and flagged for gender-related content where applicable. This research also quantified each legislator’s issue breadth by computing two indices of the dispersion of their questions across domains: a normalized entropy score (higher values indicate questions are more evenly spread across many topics) and a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of concentration (higher HHI means questions concentrate in fewer areas). For ease of interpretation, this research use the negative of HHI so that on both indices a higher value denotes greater topic diversity. These indices were calculated for each legislator-year (each member in each year), enabling a longitudinal view of issue breadth.

Statistical Analysis: This research employed regression models to test the hypothesized gender effects while controlling for other factors. For H1 (Question Format), this research used a binary logistic regression with the dependent variable indicating an oral question (=1) vs. written (=0). The key predictor was a dummy for the legislator being female, and This research included controls such as the member’s political camp (pro-establishment or opposition), seat type (geographical constituency vs. functional constituency), and indicators of seniority or leadership positions (e.g. committee chair). Year fixed effects were added to account for temporal shifts (e.g. some years overall questioning patterns might change). These controls address alternative explanations: for instance, if pro-establishment members (who are predominantly male) prefer a certain questioning style, or if functional constituency members (often focused on industry-specific issues, many of whom are male) ask fewer oral questions, our model adjusts for those factors when isolating the effect of gender.

For H2 (Policy Domain Preferences), the dependent variable is the policy domain of the question. This research employed a multinomial logistic regression to estimate how a legislator’s gender (and controls) affects the probability of a question falling into each domain category. This allows us to observe, for example, whether being female increases the likelihood of a question being about health or education. This research treated male legislators’ distribution as the reference and computed the average marginal effect (AME) of the female indicator for each domain. The writer’s primary interest is whether the female coefficient is significantly positive in social policy domains and significantly negative in economic or technical domains, as hypothesized. The same controls (party affiliation, seat type, year effects) were included to isolate gender’s influence. In Hong Kong (China), because certain domains (like finance or transport) might be associated with functional constituency members who are mostly male, these controls help ensure this research are not simply capturing constituency-specific patterns.

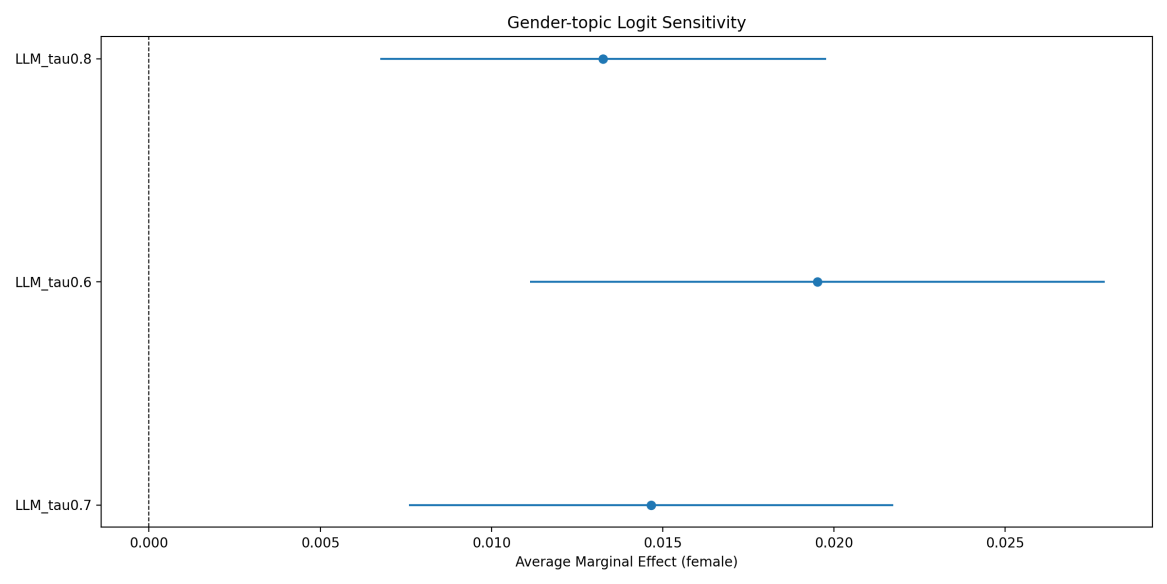

For H3 (Gender-Related Topics), this research conducted a binary logistic regression where the dependent variable indicates whether a question was classified as gender-related (1 if yes, 0 if no). The key predictor is again the female legislator dummy, with similar controls (party, etc.) included. This model tests whether female LegCo members are more likely in general to bring up women’s and gender equality issues, even after accounting for other factors. This research also performed sensitivity analyses by varying the stringency of the “gender-related” definition (e.g. requiring explicit mention of women for a narrow definition, or including implicit gender concerns for a broader definition) and found the female effect robust under these variations.

For H4 (Issue Breadth), this research ran ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions (and panel regressions with legislator fixed effects for robustness) on the diversity indices (entropy and –HHI). Each observation in these models is a legislator-year. The dependent variable is the entropy or negative HHI of that member’s questions in that year. The key independent variable is the legislator’s gender (female=1), and this research control for the total number of questions the member asked that year (since asking more questions naturally allows covering more topics). Year fixed effects are included, and in the panel specification This research also incorporate legislator fixed effects to account for unobserved individual traits. A significantly positive coefficient on female for entropy (or significantly negative for HHI) would indicate that female legislators tend to cover a more diverse range of topics in their questioning than male legislators.

All models use robust standard errors to address heteroskedasticity, and statistical significance is evaluated at conventional levels (p < 0.05 as moderate evidence, p < 0.01 as strong evidence). Below, this research report descriptive findings and regression results corresponding to each hypothesis.

3. Results

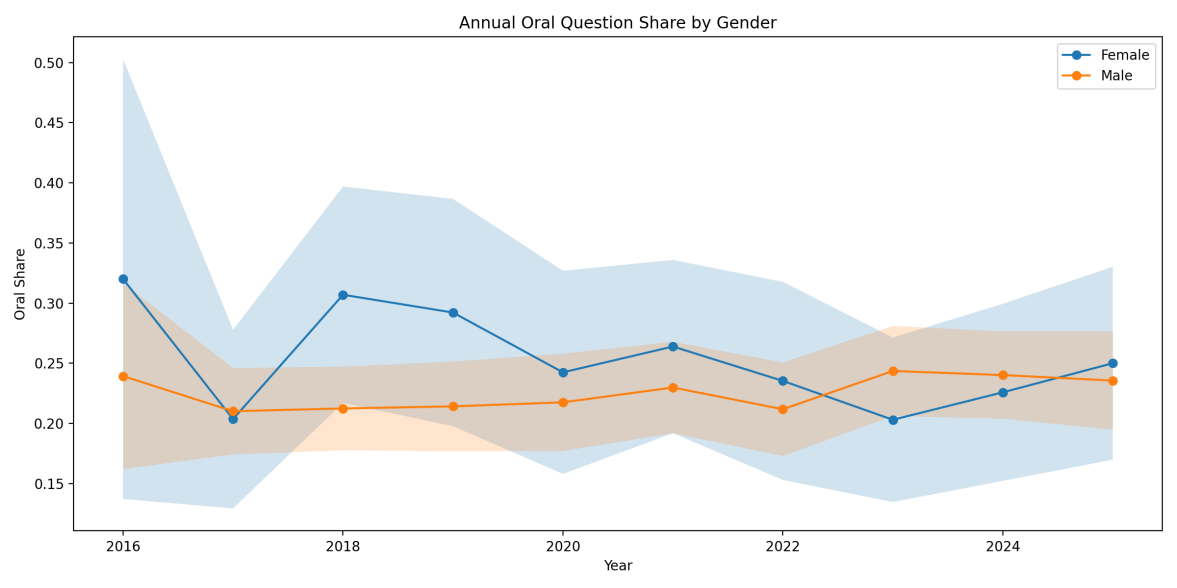

Descriptive Overview: From 2016 to 2025, LegCo members asked roughly 600 questions per year on average. Female legislators’ share of total questions each year was roughly proportional to their share of seats, about 15–20%. Thus, in terms of participation quantity, women as a group did not lag behind men – relative to their numbers, they were neither conspicuously silent nor excessively outspoken. However, a clear gender difference emerged in the format of questions. Female LegCo members showed a marked preference for asking questions orally on the chamber floor compared to their male colleagues. Overall, about 26% of questions raised by women were oral, versus about 22% of those by men, a gap of ~4 percentage points.

As shown in Figure 1, female legislators consistently raised a higher proportion of oral questions than men throughout 2016–2025, even accounting for yearly fluctuations. In 2016, about one-third of women’s questions were oral compared with roughly one-quarter for men, and this gap persisted through 2025. This pattern supports H1, suggesting that women legislators strategically favored the more public on-floor format to enhance visibility and signal engagement despite being a minority.

Substantively, clear gender differences emerged in policy focus. Female members concentrated on public health, community and internal affairs, and law and justice, whereas male members prioritized finance, economy, and infrastructure. For example, nearly 20 percent of women’s questions concerned health (versus 11 percent for men), while men devoted about 14 percent to financial issues (versus 9 percent for women). These contrasts illustrate a “social versus technical” divide: women emphasized social welfare and community concerns, while men focused more on economic and structural matters.

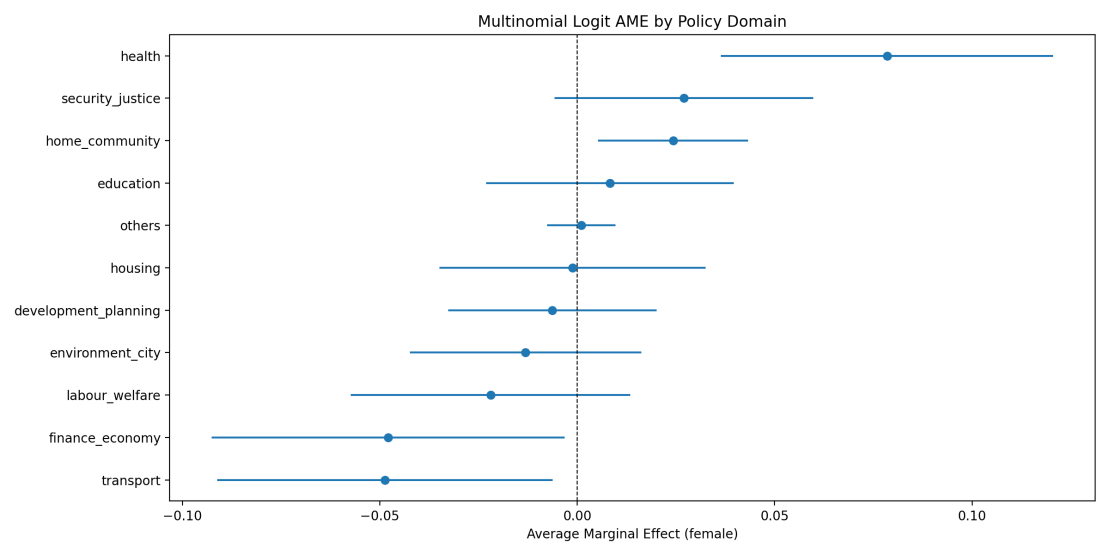

To rigorously test H2, this research used regression to control for confounding factors. The results strongly confirm the gender gap in policy priorities. Women legislators were significantly more likely than men to direct their questions to certain social policy areas, and significantly less likely in some economic/technical areas, even when holding other variables constant. Figure 2 presents the estimated effect of legislator gender on the probability of a question falling into selected key domains, based on a multinomial logit model. Each point in the figure represents the female vs. male difference in probability (average marginal effect) for that domain, with 95% confidence intervals.

As shown in Figure 2, regression estimates confirm a robust gender gap in policy focus. Holding party affiliation and constituency constant, female legislators were significantly more likely to raise questions on public health (+7.8 pp, p < 0.01) and community & home affairs (+2.4 pp, p < 0.05). In contrast, they were less likely to question government actions in finance/economy (–4.8 pp, p < 0.05) and transport & infrastructure (–4.9 pp, p < 0.05). Other domains showed smaller, non-significant differences.

Overall, these findings strongly support H2: female LegCo members consistently prioritize social-welfare and community issues, while male members focus more on economic and infrastructural matters. This “pro-social, less-economic” pattern mirrors cross-national evidence and remains robust even after controlling for institutional and partisan factors.

Next, H3 tests whether legislators differ in attention to gender-related issues. As shown in Figure 3, such questions formed only a small portion of total inquiries, yet female members were overwhelmingly responsible for them. About 3.3% of women’s questions addressed gender equality or women’s rights, compared with 1.3% for men. Across nearly every year from 2016–2025, women consistently raised a larger share of “women’s issues.” Logistic regression confirms this gap: the female coefficient remains positive and significant, even under alternative definitions. These results support H3, indicating that female LegCo members serve as the primary advocates for women’s interests—posing questions on discrimination, caregiving, and workplace equality—while men rarely initiate such inquiries.

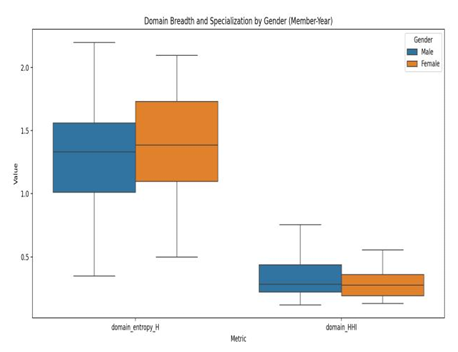

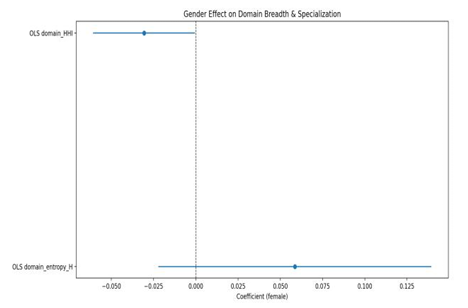

Finally, H4 examines whether female legislators engage across a broader range of issues. As shown in Figures 4 and 5, women’s questions display greater topic diversity and less concentration. On average, a female LegCo member’s questions were distributed more evenly across policy domains, while male members tended to focus on fewer areas. The OLS regression on the HHI (issue concentration index) shows a female coefficient of –0.03 (p < 0.05), indicating women’s questions are about three percentage points less concentrated. The entropy measure also shows a positive female effect, suggesting broader coverage across topics. Together, these findings support H4, demonstrating that women legislators act as policy “generalists” rather than being confined to a few “soft” domains.

This pattern aligns with research from other countries showing that women lawmakers deliberately diversify their agendas to avoid being labeled as single-issue actors and to demonstrate competence across all policy areas. In Hong Kong, China’s context, female LegCo members similarly appear to assert themselves as well-rounded policymakers, not merely advocates for social welfare or women’s concerns.

Beyond content, no significant gender differences were found in questioning style or quality. Supplementary text analysis of question titles (length, use of statistics, tone) revealed negligible variation. Both female and male legislators displayed comparable professionalism and directness, indicating that observed differences stem from issue prioritization, not from capability or communication style.

In summary, our analyses largely validate all four hypotheses. Compared to their male colleagues, Hong Kong, China’s female legislators showed a consistent set of tendencies in their questioning behavior: they more often opted for the high-visibility oral questioning format, focused more on health, community and other social domains (while de-emphasizing finance and infrastructure), were more active in raising gender-equality concerns, and engaged with a wider array of topics rather than a narrow subset. These results paint a clear picture of how gender shapes legislative oversight in Hong Kong(China) and set the stage for further interpretation and implications.

4. Discussion

This study reveals that female legislators in Hong Kong, China’s LegCo, though few in number, exhibit distinct patterns of parliamentary questioning that both reflect and reinforce their role as substantive representatives of women and community interests. The findings resonate with international literature on gender and politics while also highlighting nuances of Hong Kong,China’s context.

First, our evidence strongly supports the idea that descriptive representation can lead to substantive representation. Female LegCo members used their questions to spotlight issues traditionally associated with women’s perspectives – from healthcare and social welfare to gender equality – significantly more than male members did. This aligns with the theory of the “politics of presence” that having women in office is crucial for raising previously neglected issues affecting women [8]. Consistent with studies of other legislatures, Hong Kong, China’s women legislators acted as critical actors who advanced women’s substantive interests despite being a small minority. Notably, Hong Kong, China’s case confirms such patterns in a semi-democratic setting. Similar dynamics have been observed in Singapore’s authoritarian parliament, where female MPs likewise took on the role of representing women’s concerns in parliamentary questions [9]. These cases suggest that even under constrained or non-This researchstern political systems, female legislators tend to fulfill a unique advocacy role for women’s issues.

At the same time, our results refute any simplistic notion that women only care about “women’s issues.” On the contrary, Hong Kong, China’s female legislators demonstrated broad policy engagement. They participated in debates on law and order, environmental planning, labor rights, and more, in addition to the social sectors where they outshone men. This finding reinforces the argument by Childs and Krook [10] that what matters is not a “critical mass” of women but the presence of critical actors – individuals who, given the opportunity, will actively represent women’s interests and also integrate into all areas of policy. Even as tokens in a male-dominated body, Hong Kong, China’s women made their mark across the policy spectrum. Our findings mirror evidence from Pakistan and Australia: female legislators can be as policy-generalist and ambitious as males [11,12]. The breadth of issues women covered in LegCo may be a deliberate strategy to avoid marginalization. With only ~15% of seats, Hong Kong(China)’s women lawmakers likely felt pressure to prove their competence broadly. By not confining themselves to a narrow agenda, they countered stereotypes and expanded their influence. This reflects a broader trend of women politicians breaking out of traditional molds and asserting their expertise in “hard” policy realms as well.

Another notable point is the strategic use of question format. This research found that women were more inclined to ask oral questions on the floor, which tend to attract more immediate public attention. This behavior suggests that female legislators actively sought visibility and a platform for their issues. In the context of Hong Kong(China), where female voices are a minority, taking the stage through oral questions can amplify their impact. This corresponds with the idea that when facing a “token” situation (a small proportion in a larger group), women may over-perform or take extra measures to have their contributions noticed. By contrast, male legislators, who constitute the majority, might not feel the same imperative for visibility. The fact that Hong Kong, China’s female members matched their male peers in question volume (proportional to their numbers) and even exceeded them in oral questioning proportion indicates a proactive approach to lawmaking and oversight. It underlines that the women were eager to fulfill their legislative duties and to be seen doing so, challenging any biases about women being less engaged. This finding is encouraging: it shows that having even a few women in the legislature can make a difference in how legislative oversight is conducted – women will seize available tools (like oral questions) to raise important issues and assert their presence.

The study’s findings also have practical implications. They suggest that increasing the number of women in LegCo could further enrich and diversify the policy discourse. The current female legislators have shown they bring different priorities and a broad approach to oversight; additional women could amplify these effects and share the representational load for women’s interests that presently falls on very few shoulders. Policymakers and political stakeholders should consider measures to support women’s legislative participation. This can include recruitment and training programs for potential female candidates, resources to help female legislators succeed in office, and efforts to ensure media portrayal of women politicians is fair and highlights their contributions. Institutional reforms toward gender mainstreaming in the legislature could also be beneficial – for instance, adjusting rules or agendas to better accommodate issues concerning women and families, or creating caucuses and channels for women members to collaborate across party lines. Our results show that women legislators are fully capable of robust, professional engagement; what they need is greater presence and perhaps a more enabling environment to maximize their impact.

Finally, this research contributes to the comparative understanding of gendered legislative behavior by providing empirical evidence from Hong Kong, China, a case with both authoritarian features and a low proportion of women. It demonstrates that theories developed largely in western democracies – such as women’s propensity to champion social issues or the concept of surrogate representation – are applicable in the Hong Kong, China’s context. However, the Hong Kong, China’s case also underscores the importance of context: cultural, institutional, and political factors (like the functional constituency system, or the unique socio-political events of the past decade) can modulate how gender differences manifest. Future research could delve deeper into how these factors interact with legislator gender. For example, do female legislators in the opposition versus pro-establishment camp behave differently in questioning? How did specific events (e.g. political upheavals, protests) influence the issues women raised? Additionally, as Hong Kong, China’s political landscape evolves (notably with recent electoral changes), it will be important to monitor whether these gendered patterns persist or change.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study finds that female legislators in Hong Kong, China’s Legislative Council, despite their small numbers, have a measurable and multifaceted impact on legislative oversight through questions. They not only shine a spotlight on health, community welfare, and gender equality issues to a greater extent than men, but also actively engage across a wide range of policy topics and utilize strategic avenues like oral questions to enhance their visibility. In terms of questioning style and rigor, women perform on par with their male colleagues, dispelling any notion of lesser competence. These results update and extend earlier analyses by showing clear gender-based patterns in the past decade of LegCo activity. The Hong Kong, China’s case thus enriches the global evidence that women’s descriptive underrepresentation can lead to differences in substantive representation, even under political constraints. Our findings lend credence to calls for increasing women’s presence in government, as doing so is likely to broaden the agenda and ensure that issues of importance to women and communities are not overlooked. Supporting and empowering the few women who do make it into legislature is equally crucial – they have proven capable of leveraging the tools at their disposal to serve as effective representatives. Efforts such as capacity-building for female legislators, media strategies to highlight women’s contributions, and reforms to parliamentary procedures to be more inclusive of diverse perspectives are recommended. In conclusion, gender matters in legislative oversight: even in a semi-authoritarian legislature like Hong Kong, China’s women lawmakers bring different priorities and approaches that ultimately enhance the deliberative function and representativeness of the body. Strengthening female representation can therefore be seen as a step toward a more responsive and inclusive governance in Hong Kong (China) and beyond.

References

[1]. Congressional Research Service. (2024, December 10). Statistics on women in national governments around the world (CRS Report No. R45483). Congress.gov.

[2]. Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes.” Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.*

[3]. Wängnerud, L. (2009). Women in parliaments: Descriptive and substantive representation. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 51–69.* [4] Barnes, T. D. (2012). Gender and legislative preferences: Evidence from the Argentine provinces. Politics & Gender, 8(4), 483–507 [5]. Bird, K. (2005). Gendering parliamentary questions. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 7(3), 353–370.

[4]. Höhmann, D. (2020). When do men represent women’s interests in Parliament? How the presence of women in Parliament affects the legislative behavior of male politicians. Swiss Political Science Review, 26(1), 31–50.

[5]. Tam, W. (2018). Women representing women? Evidence from Hong Kong, China’s semi-democratic legislature. Representation, 53(1), 1–18.*

[6]. Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Oxford University Press.

[7]. Tam, W. (2020). Parliamentary questions and women’s substantive representation in authoritarian legislatures: Evidence from Singapore. Journal of Legislative Studies, 26(2), 249–268.*

[8]. Childs, S., & Krook, M. L. (2009). Analysing women’s substantive representation: From critical mass to critical actors. Government and Opposition, 44(2), 125–145

[9]. . Khan, N. (2018). Women legislators and their interests in policy making in Pakistan: A study of private members’ bills presented in National Assembly during 2010–15. Pakistan Annual Research Journal, 54(1), 218–235.*

[10]. Vacaflores, I., & Stephenson, E. (2025). Understanding female legislators’ substantive representation in the Australian Parliament. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 60(1), forthcoming.* Author accepted manuscript available from Griffith University. https: //doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2025.2507550

Cite this article

Zhang,C. (2025). Gender Differences in Questioning Behavior in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, China. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,122,44-53.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceeding of ICSPHS 2026 Symposium: Critical Perspectives on Global Education and Psychological Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Congressional Research Service. (2024, December 10). Statistics on women in national governments around the world (CRS Report No. R45483). Congress.gov.

[2]. Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes.” Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.*

[3]. Wängnerud, L. (2009). Women in parliaments: Descriptive and substantive representation. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 51–69.* [4] Barnes, T. D. (2012). Gender and legislative preferences: Evidence from the Argentine provinces. Politics & Gender, 8(4), 483–507 [5]. Bird, K. (2005). Gendering parliamentary questions. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 7(3), 353–370.

[4]. Höhmann, D. (2020). When do men represent women’s interests in Parliament? How the presence of women in Parliament affects the legislative behavior of male politicians. Swiss Political Science Review, 26(1), 31–50.

[5]. Tam, W. (2018). Women representing women? Evidence from Hong Kong, China’s semi-democratic legislature. Representation, 53(1), 1–18.*

[6]. Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Oxford University Press.

[7]. Tam, W. (2020). Parliamentary questions and women’s substantive representation in authoritarian legislatures: Evidence from Singapore. Journal of Legislative Studies, 26(2), 249–268.*

[8]. Childs, S., & Krook, M. L. (2009). Analysing women’s substantive representation: From critical mass to critical actors. Government and Opposition, 44(2), 125–145

[9]. . Khan, N. (2018). Women legislators and their interests in policy making in Pakistan: A study of private members’ bills presented in National Assembly during 2010–15. Pakistan Annual Research Journal, 54(1), 218–235.*

[10]. Vacaflores, I., & Stephenson, E. (2025). Understanding female legislators’ substantive representation in the Australian Parliament. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 60(1), forthcoming.* Author accepted manuscript available from Griffith University. https: //doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2025.2507550