1. Introduction

Nowadays, both work and life as well as leisure and entertainment all require a certain approach - socializing. The term "socializing" has become a popular search term in recent years as its significance has increasingly come to light. Therefore, people's proficiency in socializing divides them into two categories. Those who are not good at socializing tend to experience emotions and behaviors such as tension, anxiety, and helplessness in social settings. Often, the best way for others to judge this is by observing whether they blush.

Blushing is related to cognitive processes, mainly manifested in the activity of brain regions, and has nothing to do with mentalization. Then, most blushing is accompanied by self-conscious emotions, but people do not know what the mechanism of blushing is [1]. This has led to two debates about whether blushing is related to self-awareness of emotions or to higher-level cognitive processes. The process of higher-level cognitive processes refers to the process by which a person reflects on themselves and begins to worry about what others think of him or her, or about negative evaluations.

This research aims to clarify the origin of blushing, so that people who suffer from social anxiety and may be affected in their normal work and life can solve their problems in a targeted manner. The experiment also revealed many limitations, such as using the increase in cheek temperature as an indicator of blushing, but in fact, blood flow measurement might provide more reliable information more quickly. Further research is needed to figure it out.

2. Literature review

2.1. Debate on blushing mechanism

Based on Darwin's blushing mechanism, blushing arises when individuals step into others’ shoes to think about themselves and recognize the possibility of being judged negatively by those around them. This is a point made by one side of the debate, but there's a greater emphasis on seeing yourself in other people's eyes when you're emotional about yourself -- recognizing that that's how you're seen, and in particular recognizing negative judgments, which can lead to blushing. Therefore, the more important point is that constantly considering the relationship between others and oneself has a significant impact.

Historically, most studies have held that blushing is closely related to social phobia, and blushing is the most prominent trait of social phobia. Therefore, most researchers have chosen to start with this trait. The final way to judge the result is mostly based on facial color and facial temperature for confirmation. In contemporary times, more in-depth research is conducted on the neural nature of facial flushing based on this trait. It is not only focused on facial color or changes in facial blood volume, but also on the measurement of facial temperature.

2.2. Neural responses associated with blushing

The activity in the brain region is closely tied to neural responses. Previous research has shown that to generate emotions, a person must find themselves in a fictional situation similar to one related to emotional cognition. However, to elicit an emotional response, one must be in a real situation rather than an illusory one. Following three studies, the mPFC and the ventral anterior insula were activated, areas associated with emotional arousal, awareness of a person's emotional and physical state, and self-reflection.

However, none of these studies specifically measured the emotional and physical responses that trigger blushing. So, to further directly measure neural responses, let's have participants watch their own videos. First, the participants were mostly teenagers, and they responded more directly and actively to various aspects of life. Second, in addition to watching their own videos, they also watched videos of other participants and professional singers to form a data comparison, making it easier to observe the blush. Finally, during their viewing, FMRI was used to detect the activity of the brain and the temperature of the cheek to more reliably record the degree of blush, ensuring the accuracy of the data.

This research observed that people tend to blush more when watching themselves sing than when viewing others performing. Overall, participants who exhibited stronger facial flushing while observing their own singing showed heightened activation in the cerebellum and in the left para-central lobule, along with greater time-locked neural responses in early visual regions. In line with prior findings, converging research suggests that the cerebellum plays a pivotal role in emotional regulation and processing. Therefore, the increased activity of cerebellar lobular V accompanied by more facial flushing may imply that individuals with more facial flushing are involved in sensor-motor matching and are more emotionally engaged.

According to the test, it can be concluded that whether blushing is related to psychosis is related to the areas of the brain that are activated.

3. Methods

3.1. Samples and data source

A total of sixty-three females aged 16 to 20 from Amsterdam took part in the research. Participants were recruited through social media platforms and the on-campus student community of the University of Amsterdam’s School of Social and Behavioral Sciences. About 63 participants from Amsterdam, were not told in advance to sing or were filmed on camera to prevent them from becoming predisposed or repulsed. Before watching the video, they were selected. First, through a social anxiety questionnaire, and then only 49 participants participated in the MRI study. Finally, due to errors in the fMRI data collection process, 9 participants were excluded, and the final sample was 40 participants.

Also called social phobia, Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is one of the most widespread and troubling psychiatric disorders. Self-reported scales are a well-recognized assessment approach, and the SPAI stands out prominently among all available scales. This instrument consists of two subcomponents: (1) the Social Phobia subscale and (2) the Agoraphobia subscale. The former measures the defining features of social anxiety, while the latter assesses fears associated with situations that are typically connected to agoraphobia, such as dread of large crowds and standing in queues. The total score for the SPAI is derived by subtracting the score obtained from the Agoraphobia subscale from the score of the Social Phobia subscale [2].

After determining the number of participants, several main impact areas were examined in the FMRI analysis.

3.2. Data collection and experimental steps

While inside the MRI scanner, participants viewed recordings featuring themselves and those of others. Crucially, they were informed that their own performances were also being observed by other participants. But at the same time, there is a tendency to generate vicarious embarrassment, which leads to incorrect results. Vicarious embarrassment is that they will consider that others will be as embarrassed as themselves, or sing at the same level, but will be less embarrassed. Video data. So, in this case, participants will also watch videos of professional singers singing, in contrast. Subsequent FMRI sessions required three sessions, each consisting of five trials, each of which consisted of three videos (one's own, another's, and a professional singer's), and the order in which the three videos were presented to participants was random.

Studying the neural matrix of facial flushing can clarify the psychological processes behind facial flushing and the mechanisms involved in self-awareness. In contrast to blood flow measurements typically employed to assess blushing, temperature-based measurement is less susceptible to artifacts and provides a more stable signal, allowing for the detection of gradual and pronounced changes in facial coloration.

In terms of participants' behavior and measurement, participants fill out a social fear and anxiety form in the early stage of recruitment and determine whether they can participate in the trial based on their scores. There are 48 and 29 points, and those who score above 48 or below 29 can become participants. They are people with high and low levels of social fear and anxiety, respectively. Among them, this questionnaire is reliable enough.

The most important part of the experiment was to capture the cheek temperature, using the TSD202 series thermistor sensor to test the cheek temperature, measuring the blush index as the increase in cheek temperature from 12 seconds before stimulation to 24 seconds after the video was shown to the participants.

In terms of study design, the average blushing response of participants under different experimental conditions was used as a dependent variable, and the temperature increase was quantified by accurately measuring the 12-second baseline to the 24-second trial period. The experimental conditions were set to include three levels of intra-body factors, including self, others, and professional, and the random intercept of the subject level was considered. A mixed-effect regression model (Wilkinson symbol: 'blushing~ condition + (1 | subject) ') was constructed to comprehensively consider experimental factors and individual differences.

In data analytics, a variety of statistical methods are used to ensure the reliability of the results. On the one hand, a linear test is performed in the mixed-effect regression model to carefully check the effect combination, and at the same time, the normality, collinearity and homoscedasticity of the residual distribution of the model are strictly checked to ensure the validity of the model at the basic level. On the other hand, Bayesian repeated measurement variance analysis is used in parallel. By comparing with the empty model, the fixed null hypothesis prior probability is 0.5 corrected multiple tests. After judging the residual performance with the help of Q-Q graphs, parameter estimation is carried out, and individual comparison is carried out based on the default t-test of the Cauchy prior.

3.3. Data processing and analysis

The preprocessing and analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data were conducted using AFNI. Functional images were first despiked, denoised, and corrected for slice timing to ensure temporal alignment across slices. Motion correction was performed via six-parameter rigid-body realignment, during which the functional data were co-registered to each participant’s T1-weighted anatomical image. The T1 image, after skull stripping, was normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template using nonlinear warping, and the resulting transformation parameters were applied to the functional data.

Motion estimates were retained as nuisance regressors in subsequent modeling to control for motion-related variance. Spatial smoothing was applied with a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM), and each voxel’s time series was scaled to a mean of 100 to generate percentage signal change for interpretability. Preprocessing quality was verified using AFNI’s internal diagnostic tools through direct visual inspection.

At the group-analysis level, intersubject correlation (ISC) was computed to measure the similarity of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses among participants exposed to the same stimuli. Fisher z-transformed ISC maps were analyzed with the 3dISC module in AFNI using voxelwise linear mixed-effects models. An additional ISC model incorporating the continuous variable Blushing was used to identify regions where neural activity patterns covaried with individual blushing responses. Statistical significance was assessed with cluster-level thresholds, and false-positive rates were controlled by simulating noise volumes through hybrid modeling of spatial autocorrelation.

4. Result

4.1. Changes in the degree of blushing

Through the experimental conditions displayed by the mixed effect model, when watching your singing video, the cheek temperature is the highest, and the relative temperature is not adjusted at this time. Secondly, watch the singing video of professional singers, because professional singers must be higher than their singing level, so the degree of embarrassment is stronger, and the cheek temperature is relatively high.

The findings were substantiated by linear contrasts within the mixed-effects model, comparing each condition to the baseline. Facial flushing during the self condition was significantly elevated relative to the overall mean. In contrast, comparisons of the self condition with the professional condition and with the other condition yielded no significant differences. To further examine condition-specific effects, paired contrasts were conducted within the mixed-effects framework. These analyses demonstrated that blushing intensity under the self condition was significantly greater than that observed in the professional condition. However, the comparison between the self and other conditions approached but did not reach statistical significance. The contrast between the other and professional conditions was likewise non-significant.

Currently, the temperature has a relative drop. Finally, watch the video of other participants, because considering that other participants are similar to their singing level, and other participants will also know that they are watching their video, so there is an alternative embarrassment, and the cheek temperature is lower.

Figure 1: The influence of the situation on blushing

ΔT denotes the temperature change (°C) between 12 seconds prior to the onset of the video and 24 seconds following its start, serving as an indirect indicator of blushing. Each data point represents the mean ΔT value across all trials for a given participant, computed separately for the Self , Other, and Professional conditions.

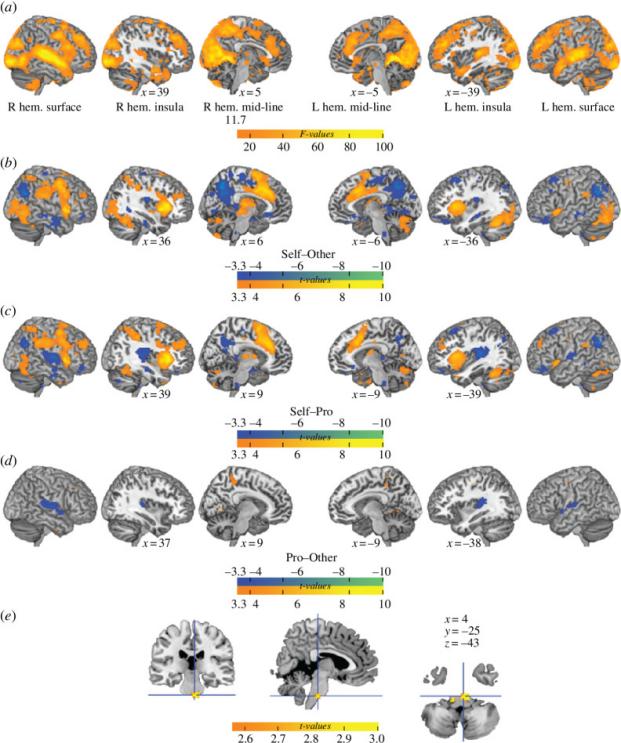

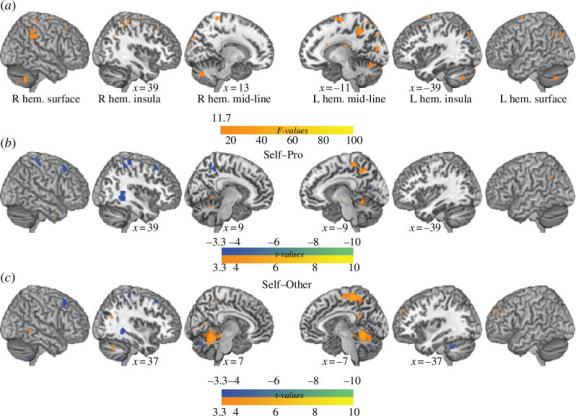

4.2. Preliminary analysis of FMRI

Blushing has been linked to heightened emotional arousal and activation within corresponding neural regions. Brain areas associated with attentional control exhibited increased induced electrical capacitance, whereas regions of the default mode network, demonstrated reduced BOLD responses [3]. This pattern primarily reflects the engagement of task-relevant neural systems. However, because the brain regions in broad psychological processes overlap considerably, distinguishing their specific contributions based solely on activation patterns remains challenging.

In particular, the participants with more blushing showed greater activity in the cerebellum and paracentric lobules. Blushing-by-Condition interactions was found that the effects on the cerebellum and the left paracentral lobe were greatest under self-conditioning.

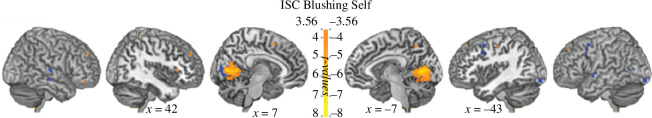

Participants who blushed more often and to a greater extent showed higher ISC in the early visual cortex. A positive correlation indicates that there are large changes in cheek temperature, with higher cheek temperatures. Negative correlation is the opposite.

This section highlights the regions showing individual differences in correlation across different subjects, as well as changes in cheek temperature within the self-condition. Positive values are represented by warm colors, and negative values by blue. A key point to emphasize is that after applying cluster size correction at 40, the negative correlations no longer hold up (i.e., lose statistical significance).

5. Discussion

Compared with previous studies, the main trait of known social phobia is blushing. From focusing on observing and measuring the color of the blush to emphasizing the degree and temperature of the blush. The common point is to consider that blushing is a trait of social phobia, starting from this basis.

Initially, to test the neural correlations of blushing, participants were selected for the experiment through a social fear and anxiety questionnaire. At the beginning of the trial, the participants watched three kinds of videos, and eventually, the participants watched their videos with the highest cheek temperature and watched other participants' videos with the lowest cheek temperature. Because they develop empathy and substitute embarrassment, the level of embarrassment is reduced, and it is difficult to capture the cheek temperature. The findings presented here suggest that blushing could be set off by processing related to the self, and that it has an association with the activation of brain areas involved in emotional arousal as well as the attention directed toward stimuli connected to the self.

Furthermore, participants who exhibited more pronounced blushing in response to watching their own singing showed heightened activation in two specific brain regions: the cerebellum (specifically the V lobule) and the left paracentral lobule. Notably, the cerebellum is known to play a vital role in the processing of emotional experiences. In an analysis in which BOLD signals were associated with changes in blushing from trial to trial or individual differences in blushing, the psychologized brain region was not significantly activated.

Including lobular V, the cerebellum plays a critical role in emotion processing [4]. Consequently, the increased activity of cerebellar lobular V that accompanies more intense facial flushing could indicate that people with more noticeable facial flushing participate in sensor-motor matching and are more emotionally invested [5].

The greater blushing, the more time the participants spent in the early visual cortex, because they were better at processing stimuli, such as visual stimuli. These self-related stimuli tend to generate emotional responses and keep themselves focused on the stimulus. So, blushing is the result of emotional processes before reflection, not mentalization.

In addition, there are still a great many limitations. First of all, only the facial flushing temperature was considered as the facial flushing index. In fact, the blood flow rate as the index is more reliable. Secondly, the neural activities discovered related to blushing when witnessing oneself singing may not necessarily be applicable to other neural activities. Thirdly, when planning the experiment, it was unexpected that specific associations related to the activities of the cerebellum and the visual cortex would be observed.

In summary, blushing is linked to neural activity within regions implicated in emotional arousal and attentional regulation. This relationship suggests that blushing may arise from heightened emotional arousal and self-focused attentional engagement, rather than from psychosomatic influences. The present findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of self-awareness, reinforcing the growing recognition of embodied experience as a key component of self-related processes. Moreover, this perspective opens promising avenues for exploring the foundations of self-awareness in infants and non-human animals.

6. Conclusion

Blushing seems to be involved with portions of the brain connected to how people feel emotionally and how aware people are. It also means that blushing is aroused by being excited emotionally, and by self-focused attention, and not by an involvement of the psyche consciously [6]. These results add to continuing ideas about how flushing works on the face, and they give more backing to the idea that high-level thinking about others is not needed for flushing to happen. Also, it opens up new areas for research on self- awareness in babies and other animals [7].

References

[1]. Leary MR, Britt TW, Cutlip WD, Templeton JL.1992. Mentally. 112, 446-460. (10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.446)

[2]. de Vente W, Majdandžić M, Voncken MJ, Beidel DC, Bogels SM. 2014. The SPAI-18 is a brief version of the Social Phobia and Anxiety Scale: Reliability and validity of clinical reference and non-reference samples. J. Anxiety disorder. 28, 140-147. (10.1016 / j.j. Anxdis 2013.05.003)

[3]. Cox RW 1996. AFNI: Software for analyzing and visualizing functional magnetic resonance neural images. Calculation. Biomedical. Res. 29, 162-173. (10.1006/CB Mr. 1996.0014)

[4]. Nakamura K. 2011. A central circuit for body temperature regulation and fever control. American Journal of Physiology - Regulation Integration. Comparative physiology. 301, R1207 - R1228. (10.1152 to 00109.2011)/ajpregu.

[5]. Bhave VM, Nectow AR. 2021. The dorsal nucleus of the middle slit controls the energy balance. Trend Neuroscience 44, 946-960. (10.1016 / j.t. ins. 2021.09.004)

[6]. Nikolic M, Di Plinio S, Sauter D, Keysers C, Gazzola V. 2024. The blushing brain: The neural matrix of cheek temperature rises due to self-observation.

[7]. Nikolic M, Di Plinio S, Sauter D, Keysers C, Gazzola V. 2024. Supplementary materials come from: The blushing brain: The neural matrix of cheek temperature increases in response to self-observation. FIG. (10.6084 / m9. Figshare. C. 7344383).

Cite this article

Yang,Y. (2025). Research on the Relationship Between Blushing and Higher-order Social Cognition. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,114,52-61.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Leary MR, Britt TW, Cutlip WD, Templeton JL.1992. Mentally. 112, 446-460. (10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.446)

[2]. de Vente W, Majdandžić M, Voncken MJ, Beidel DC, Bogels SM. 2014. The SPAI-18 is a brief version of the Social Phobia and Anxiety Scale: Reliability and validity of clinical reference and non-reference samples. J. Anxiety disorder. 28, 140-147. (10.1016 / j.j. Anxdis 2013.05.003)

[3]. Cox RW 1996. AFNI: Software for analyzing and visualizing functional magnetic resonance neural images. Calculation. Biomedical. Res. 29, 162-173. (10.1006/CB Mr. 1996.0014)

[4]. Nakamura K. 2011. A central circuit for body temperature regulation and fever control. American Journal of Physiology - Regulation Integration. Comparative physiology. 301, R1207 - R1228. (10.1152 to 00109.2011)/ajpregu.

[5]. Bhave VM, Nectow AR. 2021. The dorsal nucleus of the middle slit controls the energy balance. Trend Neuroscience 44, 946-960. (10.1016 / j.t. ins. 2021.09.004)

[6]. Nikolic M, Di Plinio S, Sauter D, Keysers C, Gazzola V. 2024. The blushing brain: The neural matrix of cheek temperature rises due to self-observation.

[7]. Nikolic M, Di Plinio S, Sauter D, Keysers C, Gazzola V. 2024. Supplementary materials come from: The blushing brain: The neural matrix of cheek temperature increases in response to self-observation. FIG. (10.6084 / m9. Figshare. C. 7344383).