1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change, rapid urbanization, and population growth, the unequal distribution of water resources has moved beyond issues of technology and infrastructure to become a central concern of social equity and human rights. Water is not only indispensable for life and health but also reflects broader patterns of social power and institutional arrangements. The distribution of water resources reveals who benefits from environmental resources and who bears their burdens [1]. It is therefore essential to ensure the provision of safe, accessible, and reliable drinking water to achieve social and environmental justice. However, despite the United Nations’ recognition in 2010 of “safe drinking water and sanitation” as a basic human right [2], and the adoption of Sustainable Development Goal 6 to provide “safe water and sanitation for all,” progress remains uneven. Current monitoring systems rely primarily on macro-level indicators such as water supply coverage and often overlooks key dimensions including water quality, affordability, service stability, and equity [3]. As a result, the water access challenges faced by vulnerable groups are systematically underestimated.

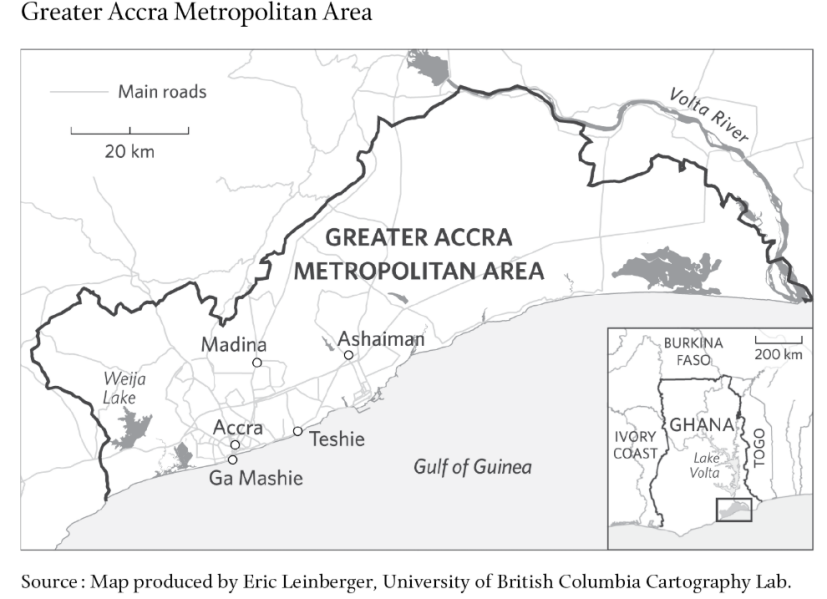

The Greater Accra Region of Ghana offers a particularly representative case. As the political and commercial center of the nation, the region has experienced tremendous growth in city expansion and substantial investment in infrastructure. However, the benefits of water resource allocation have not been fairly shared. Specifically, informal and peri-urban communities have long been excluded from the formal water supply network due to weak institutional coordination, ambiguous regulatory responsibilities, and exclusionary citizenship- or tenure-based policies. As such, this paper examines how institutional exclusion and spatial marginalization converge to produce multifaceted inequalities in access for the most vulnerable populations.

This paper addresses three questions. First, in what ways do residents in informal and peri-urban settlements encounter water inequality in the routines of daily life? Second, by what mechanisms do institutional exclusion, regulatory fragmentation, and citizenship-based barriers widen gaps in service delivery? Third, how do international policy and aid regimes condition national and municipal capacities for equitable governance?

Adopting a case-driven strategy, the study contributes to debates on water justice and environmental inequality in urban Africa, with a particular focus on the under-examined West African context. It traces how intersectional marginalization operates across scales—from neighborhood-level experiences to city-wide governance arrangements. Empirically, the analysis documents a persistent disjuncture between policy statements on water access and users’ lived realities, showing that physical availability frequently coexists with constraints of affordability, reliability, and safety. At the policy interface, the study synthesizes implications at the micro, meso, and macro levels and translates them into practical recommendations aimed at making water governance more responsive to marginalized urban residents.

2. Literature review

Recent African water-inequality scholarship has moved past a narrow focus on pipes and coverage, arguing that entrenched institutional and spatial arrangements are constitutive of distributional outcomes. Three lines of inquiry recur: (i) tracing structural drivers, (ii) evaluating uneven effects across social and spatial settings, and (iii) sharpening empirical and normative toolkits.

Institutional governance repeatedly appears as a first-order mechanism. Jaglin [4] and Chitonge et al. [5] show how governance legacies, legal exclusion, and fragmented mandates pattern water distribution across diverse African contexts; these same barriers stall the inclusivity envisioned in SDG 6 [5, 6]. Even reform agendas that foreground decentralization and participation often confront regulatory ambiguity, weak inter-agency coordination, and exclusionary eligibility rules—problems that also surface in the Ghanaian case examined here.

At the same time, another thread of literature highlights spatial disparities as compounding governance failures. Existing studies show that residents of informal settlements and peripheral urban areas experience limited access to water services due to their geographic disconnection from planned infrastructure [7-9]. This condition has often been framed conceptually as regional structural exclusion, which is prevalent in areas under fast urbanization process, such as Greater Accra. These spatial gaps are not merely technical but institutional, as urban-rural distinctions in service mandates fail to adapt to patterns of urban sprawl and informal growth [10].

The intersection of spatial marginality and institutional exclusion disproportionately burdens vulnerable social groups. Empirical studies repeatedly document that women, children, low-income households, and migrants bear the greatest costs of unequal water access – not only in terms of labor and financial strain but also in health outcomes and psychological stress [11, 12]. Whereas, the access barriers faced by other marginalized populations, such as people with disabilities, the elderly, and stateless individuals, remain underexplored in mainstream academic discourse.

Work that seeks to connect theory with practice has refined the analytical apparatus. Bell [13] articulates a tripartite model—distributive, procedural, and substantive justice—within an environmental-justice frame. Babuna et al. [14] link governance configurations to uneven access, while Boelens et al. [10] develop grassroots water-justice approaches centered on actor–knowledge–power dynamics. Yet much of this modelling remains abstract or macro-oriented and offers limited traction on how intersecting institutional and spatial inequalities shape everyday access.

Gaps remain. West African urban contexts—including Ghana—are still comparatively underrepresented; diagnostic claims often fail to translate into actionable reforms amid overlapping mandates and local implementation frictions; and global initiatives such as SDG 6 prioritize coverage indicators that can obscure fragmentation, spatial exclusion, and identity-based entitlements. To address these issues, this article focuses on Ghana’s Greater Accra Region and examines how spatial marginalization and institutional exclusion interact to produce layered inequalities in water governance across the micro, meso, and macro levels. In doing so, it contributes to debates on water justice in Africa by clarifying the intersections of governance capacity, spatial fragmentation, and lived barriers to access.

3. Methodology

The study adopts a case-based design rather than a purely statistical or model-driven approach. Water justice is situated, institutional, and spatial; inequalities are layered and often most visible among marginalized communities. A case design allows close examination of how institutional arrangements intersect with lived experience and supports explanation of causal processes and the identification of policy failures.Ghana’s Greater Accra Region was selected because prior scholarship and preliminary scoping indicate pronounced disparities in water access and marked spatial heterogeneity. This variation enables the study to probe how location-based disadvantage interacts with institutional exclusion.

Data and materials extend beyond academic publications to reports by international organizations (e.g., the United Nations, the World Bank) and non-governmental organizations. The analysis employs process tracing to reconstruct the evolution of key policies and governance decisions using policy documents, government statements, and other official records. Triangulation across these sources is used to clarify causal dynamics, implementation gaps, and shifts in policy narratives. The analytical framework is explicitly multi-scalar, organizing evidence at micro, meso, and macro levels, with attention at each tier to the spatial and institutional expression of inequality.

Furthermore, the study identifies key stakeholders within the water governance ecosystem, including municipal authorities, service providers (e.g., the Ghana Water Company Limited), community leaders, non-governmental organizations, donor agencies, and residents of underserved communities. Mapping these actors facilitates the assessment of accountability gaps and competing priorities in the pursuit of water justice.

4. Case analysis

4.1. Background of the Greater Accra

The Greater Accra Region is the smallest yet most populous administrative region in Ghana. Covering approximately 3,245 square kilometers, it is home to over 5.4 million people – about about 17% of the national population [15]. With a regional population density exceeding 1,700 people per square kilometer, nearly ten times the national average, the region experiences increasing pressure on infrastructure and public service delivery. As the country’s political and economic hub, Accra concentrates major industrial, commercial, port, and financial activities. However, this concentration of wealth coexists with persistent inequality. Urban centers and middle-income neighborhoods tend to enjoy relatively stable water and electricity supplies and well-developed transport networks, while underserved and informal settlements such as Ashaiman, Madina, and Old Fadama remain marginalized [16].

These inequalities are further reinforced by environmental pressures. Climate change, including rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and recurrent floods, has intensified stress on water supply infrastructure and heightened the vulnerability of low-income and coastal communities [17, 18]. Although the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) serves as the primary urban water provider, limited network coverage and substantial leakages – estimated at nearly 50% of total supply – leave many residents without reliable piped water [19]. Consequently, low-income households often rely on informal vendors or sachet water, which means that they must pay high prices for inconsistent quality [20].

Overall, the Greater Accra Region exemplifies how rapid urbanization, institutional fragmentation, and spatial inequality converge to produce unequal access to water resources, exposing the fundamental weaknesses of the urban water regime in Ghana.

4.2. Development of water governance in Ghana

Ghana’s water governance has gradually shifted from a centralized system to one emphasizing multi-stakeholder participation. However, issues such as ambiguities in institutional roles, weak coordination, and unequal resource distribution continue to constrain equitable access in urban areas such as Greater Accra.

In the 1990s, relevant reforms were implemented with policies of liberalization and privatization. The Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) resumed its role as the primary national utility responsible for urban water supply, while the Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) took over rural and small-town systems [21]. Rapid urbanization has since blurred these service boundaries, effectively excluding most peri-urban and informal settlements from formal water provision.

To improve coordination, Ghana adopted a Sector-Wide Approach (SWAP) with support from international partners. The initiative aimed to harmonize the efforts of communities and government agencies, but its impact has been limited by capacity constraints and slow implementation [19]. The 2024-2025 GWCL water rationing further highlights these shortcomings. Particularly, low-income households without official connections were excluded from the scheme and forced to rely on costly informal supplies [22].

Local Water Boards (LWBs), established in 2007 to promote community participation, have had minimal impact due to financial dependency and limited authority. Meanwhile, the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) regulates tariffs and service standards at the national level but focuses primarily on urban utilities, and overlooks the informal and rural networks [19].

Overall, overlapping mandates among the GWCL, CWSA, and local municipalities – combined combined with weak regulatory oversight – have produced a fragmented governance system that perpetuates spatial and institutional inequities in access to water.

5. Analysis of multi-level inequality in water issues

5.1. Micro-level inequality

At the micro scale, water access in Greater Accra exposes a durable gap between national commitments and on-the-ground delivery. Policies invoke universal access, yet implementation is uneven and fragmented, producing daily frictions for vulnerable urban residents. These frictions are most visible in informal and otherwise marginalized settlements without secure tenure or municipal infrastructure, where households depend on informal arrangements to obtain water [20].

The principal actors at this level are residents, private suppliers, and community intermediaries. In many neighborhoods, bottled-water vendors and tanker operators function as the de facto providers but often entrench inequality through opaque pricing, irregular supply, and weak accountability [19]. In the absence of effective price regulation or external oversight, these firms target higher-margin areas and bypass poorer enclaves, contributing to the “de-publicization” of water—access mediated by markets rather than guaranteed as a right. The result is a central tension in urban water governance: informal mechanisms can patch shortfalls in public systems yet simultaneously reproduce spatial and economic inequalities. Local leaders and community representatives attempt to broker relations among residents, suppliers, and officials, but their leverage is limited by weak inter-agency coordination and uncertain mandates [23].

Micro-level water insecurity manifests along three linked dimensions—deficit, cost burden, and health vulnerability. First, restricted links to formal networks push households toward intermittent or unsafe sources, generating chronic shortages that destabilize domestic routines; women often shoulder the labor of collection and household allocation, compounding physical fatigue and emotional stress [24]. Second, the price of water is disproportionately high for low-income households, which in some cases spend as much as 91% of disposable income on vendor or tanker purchases; price volatility set by private suppliers deepens financial risk [20, 22]. Third, reliance on unregulated, lower-quality sources elevates sanitation problems and disease exposure and imposes psychological strain associated with prolonged insecurity [12].

5.2. Meso-level water governance

At the meso scale, inequality in Greater Accra is produced less by physical scarcity than by coordination failures—unclear responsibilities, weak regulation, and gaps in routine governance. Peri-urban zones function as a governance gray area where urban and rural systems overlap without effective alignment; the result is no clear line of accountability for service delivery.

Fragmented mandates. Ghana’s water services are split between the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) for urban areas and Local Water Boards (LWBs) for smaller towns and rural communities [21]. As urban expansion blurs jurisdictional boundaries, LWBs have incrementally taken on peri-urban service beyond their formal remit, often without the technical capacity or finances to ensure reliability; dependence on donor funds and lean staffing further destabilize operations. By contrast, GWCL’s centralized decision routines emphasize cost recovery and efficiency, a prioritization that tends to favor higher-income neighborhoods. Marginalized and informal settlements, caught between agencies, face recurring shortfalls and higher effective prices. This pattern illustrates how overlapping mandates plus ambiguous authority translate into inequitable access.

Regulatory gaps. The Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) is tasked with tariff and service oversight, but its leverage is limited [19]. Lacking robust tools and the reach to coordinate GWCL–LWB interfaces, it struggles to enforce equitable coverage. In this vacuum, actors with greater economic weight—large industrial consumers—secure preferential access, while low-income neighborhoods remain underserved. The outcome is not simply unequal distribution but a systemic bias embedded in the governance architecture: administrative inefficiency amplifies the role of purchasing power in allocating water.

Administrative exclusion. Policy rules tied to citizenship and tenure compound these dynamics. Residents of informal or unregistered settlements frequently cannot obtain official connections absent legal documents or land titles [21]; even long-term residency or consistent payment histories may not suffice. Applications traverse multiple bodies—local authorities, GWCL offices, NGOs, and micro-finance entities—creating a cumbersome process that deters marginalized households and weakens channels for articulating demand or negotiating improvements.

5.3. Macro-level limitations

At the macro scale, inequities in Ghana’s urban water governance reflect a structural mismatch between internationally promoted policy templates and domestic implementation capacity. Despite sustained cooperation and investment, global frameworks have tended to privilege fiscal efficiency and network expansion over distributional equity, producing durable gaps in access for marginalized groups [25].

Policy transmission to domestic reform. Recent measures—tariff revisions and public–private partnership arrangements—illustrate how international models diffuse into national policy. While intended to improve efficiency and cost recovery, these instruments frequently leave out residents without formal tenure, secure housing, or proximity to piped networks; for many urban poor, affordable and reliable supply remains out of reach.

Aid architecture and its limits. Donor- and NGO-led efforts, including initiatives associated with CHF and CONIWAS, add capacity through community engagement, technical support, and targeted finance [26]. Yet short project cycles, volatile funding, and limited integration with core public institutions cap their durability and scale.

Macro-level diagnosis. The central constraint is the misalignment between globally driven orientations and the on-the-ground conditions of urban governance. Under this misfit, national and local agencies struggle to universalize fair service, and structural inequalities encoded in international governance logics persist.

6. Recommendation

At the micro level, the main problem is the “de-publicization” of water, which frames access as a technical and fiscal issue rather than a matter of entitlement. Achieving equitable access requires restoring the public nature of water through affordable, flexible, and community-centered supply models. Governments should expand community water stations, implement prepaid and mobile payment systems, and apply targeted subsidies to reduce the financial burden on low-income residents. At the same time, the role of women in water collection and community governance, as enhancing their participation can improve the inclusivity of decision-making processes. Additionally, private water suppliers should be integrated into a unified regulatory framework under the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC), ensuring uniform pricing, consistent service coverage, and protection against price exploitation [21].

At the meso level, unclear responsibilities and weak coordination between the Local Water Boards (LWBs) and the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) have produced irregular and inequitable water services in peri-urban and transitional areas. Institutional reforms should clearly define the roles and accountability mechanisms of all entities, establish inclusive service standards, and decouple water eligibility from citizenship status, guaranteeing access to basic water for all residents. Local governments should be granted greater fiscal and regulatory authority to enhance transparency and responsiveness in resource allocation. Regulatory institutions such as the PURC must balance economic efficiency with social equity in performance assessments, as well as maintain oversight to prevent the overconsumption of limited public supplies by trial or private users [19].

At the macro level, while global cooperation has contributed to improvements in Ghana’s water governance, its benefits are unevenly distributed. International projects often emphasize efficiency, coverage, and cost recovery, but they frequently overlook local implementation challenges and the practical constraints faced by marginalized populations. Future policy initiatives should embed equity and institutional justice in the design and evaluation of projects, ensuring that international support translates into meaningful local impact. Ghana can also benefit from learning from other nations’ experiences in localizing international governance frameworks. Furthermore, establishing long-term, stable partnerships with international counterparts can strengthen infrastructure investment and governance capacity. Simultaneously, reducing reliance on short-term, one-off projects and aligning national development goals with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 6 will promote more inclusive and sustainable water and sanitation outcomes.

7. Conclusion

Evidence from Greater Accra shows that overlapping mandates, spatial marginalization, and fragmented responsibilities jointly reproduce water inequality. Despite reforms framed around decentralization and efficiency, informal settlements and peri-urban districts remain weakly integrated into stable network supply. National bodies retain control over capital and priority setting, while local authorities shoulder implementation with thin resources; limited oversight of industrial and private suppliers further skews distribution.

Two implications follow. First, restoring water’s public character at the micro scale requires access pathways that are affordable, flexible, and community-anchored irrespective of residence status. Second, meso-level accountability depends on clarifying the respective authority of the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL), Local Water Boards (LWBs), and the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) and on routine coordination across these interfaces.

At the macro scale, international partners should recalibrate support from narrow efficiency gains toward locally embedded capacity and durable infrastructure. When micro-level access schemes, meso-level mandate clarity, and macro-level capacity building are pursued in concert, national commitments can translate into more reliable, inclusive urban water provision.

References

[1]. Zwarteveen, M., & Boelens, R. (2014). Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: Some conceptual building blocks for research and action. Water International, 39(2), 143–158. https: //doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.891168

[2]. United Nations. (2010). The human right to water and sanitation (Resolution A/RES/64/292). United Nations General Assembly.

[3]. United Nations. (2018). Sustainable Development Goal 6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. United Nations.

[4]. Jaglin, S. (2022). Water resources and socio-spatial inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: Legacies, clues and research agenda. In Jaglin, S., & Zérah, M.-H. (Eds.), Undisciplined Environments: Spaces, Politics and Practices in the Global South (pp. 157–176). Springer. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60502-4_8

[5]. Chitonge, H., Mokoena, A., Kongo, M. (2020). Water and Sanitation Inequality in Africa: Challenges for SDG 6. In: Ramutsindela, M., Mickler, D. (eds) Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14857-7_20

[6]. Yalew, S. G., Kwakkel, J., & Doorn, N. (2021). Distributive justice and sustainability goals in transboundary rivers: Case of the Nile Basin. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 8, Article 590954. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.590954

[7]. Rossi, Maurizio, and Marina Fischer-Kowalski. Dimensions of Inequality in Urban and Rural Water Use and Water Accessibility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 12.2 (2020): 574. https: //doi.org/10.3390/su12020574

[8]. Pullan, R. L., Freeman, M. C., Gething, P. W., & Brooker, S. J. (2014). Geographical inequalities in use of improved drinking water supply and sanitation across sub-Saharan Africa: Mapping and spatial analysis of cross-sectional survey data. PLOS Medicine, 11(4), e1001626. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001626

[9]. Enqvist, J., Ziervogel, G., Metelerkamp, L., van Breda, J., Dondi, N., Lusithi, T., Mdunyelwa, A., Mgwigwi, Z., Mhlalisi, M., Myeza, S., Nomela, G., October, A., Rangana, W., & Yalabi, M. (2022). Informality and water justice: community perspectives on water issues in Cape Town’s low-income neighbourhoods. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38(1), 108–129. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2020.1841605

[10]. Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2023). Riverhood: Political ecologies of socionature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. In Riverhood: The Politics of Socionature in the Struggle for Water Justice (pp. 1–31). Routledge. https: //doi.org/10.4324/9781003246805-1

[11]. Graham, J. P., Hirai, M., & Kim, S. S. (2016). An analysis of water collection labor among women and children in 24 sub-Saharan African countries. PLOS ONE, 11(6), e0155981. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155981

[12]. Kangmennaang, J., Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). “We are drinking diseases”: Perception of water insecurity and emotional distress in urban slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 890.https: //doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

[13]. Bell, K. (2016). Bread and roses: A gender perspective on environmental justice and public health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(10), 1005.

[14]. Babuna, P., Yang, X., Tulcan, R. X. S., Bian, D., Takase, M., Guba, B. Y., Han, C., Awudi, D. A., & Li, M. (2023). Modeling water inequality and water security: The role of water governance. Journal of Environmental Management, 326, 116815. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116815

[15]. Dongzagla, A., Dordaa, F., & Agbenyo, F. (2022). Spatial inequality in safely managed water access in Ghana. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(12), 869–882. https: //doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2022.099

[16]. World Bank. (2024). Ghana’s climate vulnerability profile. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[17]. Padi, M., Foli, B. A. K., Nyadjro, E. S., Owusu, K., & Wiafe, G. (2021). Extreme rainfall events over Accra, Ghana in recent years. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s41976-021-00052-3

[18]. Mojekwu, J. N., Nani, G., Ogunsumi, L., Tetteh, M. U. S., Awere, M. E., Pardie-Ocran, M. S., & Bamfo-Agyei, M. E. ARCA.

[19]. Tsai, A. C., & Boateng, G. O. (2021). Water insecurity: Insights from underserved communities in Accra, Ghana. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. https: //www.amacad.org/publication/water-insecurity-insights-underserved-accra-ghana

[20]. Atsugah, E. J., & John, A. (2025, June 27). Ghana’s water emergency: Unraveling the layers of crisis, inequity, and urgent reform. Amandla! Retrieved from https: //www.amandla.org.za/ghanas-water-emergency-unraveling-the-layers-of-crisis-inequity-and-urgent-reform/

[21]. Citi Newsroom. (2025, April 16). Water crisis hits Accra; residents, businesses struggle to cope. https: //citinewsroom.com/2025/04/water-crisis-hits-accra-residents-businesses-struggle-to-cope/

[22]. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2021). 2021 Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Results. Accra.

[23]. Ghana News Agency. (2025). Kpone residents express frustration over persistent water shortages. Retrieved from https: //gna.org.gh/2025/02/kpone-residents-express-frustration-over-persistent-water-shortages/

[24]. Achore, M., & Bisung, E. (2023). Coping with water insecurity in urban Ghana: Patterns, determinants and consequences. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 13(2), 150–163. https: //doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2023.203

[25]. Ainuson, K. G. (2010). Urban water politics and water security in disadvantaged urban communities in Ghana. African Studies Quarterly, 11(4), 59–77.

[26]. Morinville, C., & Harris, L. M. (2014). Participation, politics, and panaceas: exploring the possibilities and limits of participatory urban water governance in Accra, Ghana. Ecology and Society, 19(3), 36. http: //dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06623-190336

Cite this article

Zhao,J. (2025). Water Justice and Urban Inequality in Ghana: Institutional and Spatial Exclusion in Greater Accra. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,116,40-48.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceeding of ICSPHS 2026 Symposium: Urban Industrial Innovation and Resilience-oriented Regional Transformation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zwarteveen, M., & Boelens, R. (2014). Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: Some conceptual building blocks for research and action. Water International, 39(2), 143–158. https: //doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.891168

[2]. United Nations. (2010). The human right to water and sanitation (Resolution A/RES/64/292). United Nations General Assembly.

[3]. United Nations. (2018). Sustainable Development Goal 6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. United Nations.

[4]. Jaglin, S. (2022). Water resources and socio-spatial inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: Legacies, clues and research agenda. In Jaglin, S., & Zérah, M.-H. (Eds.), Undisciplined Environments: Spaces, Politics and Practices in the Global South (pp. 157–176). Springer. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60502-4_8

[5]. Chitonge, H., Mokoena, A., Kongo, M. (2020). Water and Sanitation Inequality in Africa: Challenges for SDG 6. In: Ramutsindela, M., Mickler, D. (eds) Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14857-7_20

[6]. Yalew, S. G., Kwakkel, J., & Doorn, N. (2021). Distributive justice and sustainability goals in transboundary rivers: Case of the Nile Basin. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 8, Article 590954. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.590954

[7]. Rossi, Maurizio, and Marina Fischer-Kowalski. Dimensions of Inequality in Urban and Rural Water Use and Water Accessibility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 12.2 (2020): 574. https: //doi.org/10.3390/su12020574

[8]. Pullan, R. L., Freeman, M. C., Gething, P. W., & Brooker, S. J. (2014). Geographical inequalities in use of improved drinking water supply and sanitation across sub-Saharan Africa: Mapping and spatial analysis of cross-sectional survey data. PLOS Medicine, 11(4), e1001626. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001626

[9]. Enqvist, J., Ziervogel, G., Metelerkamp, L., van Breda, J., Dondi, N., Lusithi, T., Mdunyelwa, A., Mgwigwi, Z., Mhlalisi, M., Myeza, S., Nomela, G., October, A., Rangana, W., & Yalabi, M. (2022). Informality and water justice: community perspectives on water issues in Cape Town’s low-income neighbourhoods. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38(1), 108–129. https: //doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2020.1841605

[10]. Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2023). Riverhood: Political ecologies of socionature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. In Riverhood: The Politics of Socionature in the Struggle for Water Justice (pp. 1–31). Routledge. https: //doi.org/10.4324/9781003246805-1

[11]. Graham, J. P., Hirai, M., & Kim, S. S. (2016). An analysis of water collection labor among women and children in 24 sub-Saharan African countries. PLOS ONE, 11(6), e0155981. https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155981

[12]. Kangmennaang, J., Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). “We are drinking diseases”: Perception of water insecurity and emotional distress in urban slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 890.https: //doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

[13]. Bell, K. (2016). Bread and roses: A gender perspective on environmental justice and public health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(10), 1005.

[14]. Babuna, P., Yang, X., Tulcan, R. X. S., Bian, D., Takase, M., Guba, B. Y., Han, C., Awudi, D. A., & Li, M. (2023). Modeling water inequality and water security: The role of water governance. Journal of Environmental Management, 326, 116815. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116815

[15]. Dongzagla, A., Dordaa, F., & Agbenyo, F. (2022). Spatial inequality in safely managed water access in Ghana. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(12), 869–882. https: //doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2022.099

[16]. World Bank. (2024). Ghana’s climate vulnerability profile. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[17]. Padi, M., Foli, B. A. K., Nyadjro, E. S., Owusu, K., & Wiafe, G. (2021). Extreme rainfall events over Accra, Ghana in recent years. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s41976-021-00052-3

[18]. Mojekwu, J. N., Nani, G., Ogunsumi, L., Tetteh, M. U. S., Awere, M. E., Pardie-Ocran, M. S., & Bamfo-Agyei, M. E. ARCA.

[19]. Tsai, A. C., & Boateng, G. O. (2021). Water insecurity: Insights from underserved communities in Accra, Ghana. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. https: //www.amacad.org/publication/water-insecurity-insights-underserved-accra-ghana

[20]. Atsugah, E. J., & John, A. (2025, June 27). Ghana’s water emergency: Unraveling the layers of crisis, inequity, and urgent reform. Amandla! Retrieved from https: //www.amandla.org.za/ghanas-water-emergency-unraveling-the-layers-of-crisis-inequity-and-urgent-reform/

[21]. Citi Newsroom. (2025, April 16). Water crisis hits Accra; residents, businesses struggle to cope. https: //citinewsroom.com/2025/04/water-crisis-hits-accra-residents-businesses-struggle-to-cope/

[22]. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2021). 2021 Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Results. Accra.

[23]. Ghana News Agency. (2025). Kpone residents express frustration over persistent water shortages. Retrieved from https: //gna.org.gh/2025/02/kpone-residents-express-frustration-over-persistent-water-shortages/

[24]. Achore, M., & Bisung, E. (2023). Coping with water insecurity in urban Ghana: Patterns, determinants and consequences. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 13(2), 150–163. https: //doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2023.203

[25]. Ainuson, K. G. (2010). Urban water politics and water security in disadvantaged urban communities in Ghana. African Studies Quarterly, 11(4), 59–77.

[26]. Morinville, C., & Harris, L. M. (2014). Participation, politics, and panaceas: exploring the possibilities and limits of participatory urban water governance in Accra, Ghana. Ecology and Society, 19(3), 36. http: //dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06623-190336