1. Introduction

This study focuses on the motivations, perceptions, and impacts of teenagers' high internet penetration on running their own media and being a peer viewer of other teenagers' media; the study has implications for exploring the development of minors' internet use and mental development, the future possibilities of teenagers' self-media operations, and the potential negative impacts; questionnaires were used and relevant literature was searched and read to help collect information and conduct comparative analyses. The final objective of this study is to investigate the influence of operating and following peer accounts on minors, and whether there are any gender differences during the process.

2. The Current Development of We-Media

With the advancement of the Internet, all kinds of online media platforms have become the main sources of entertainment and information acquisition for underage Internet users. According to "The 52nd Statistical Report on China's Internet Development" that the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC) released, as of June 2023, China's Internet users have reached 1.079 billion, the Internet penetration rate has reached 76.4%, of which underage Internet users accounted for 18.7%, and the penetration rate of underage Internet users is at a higher level compared to the overall [1]. In the high level of Internet penetration in daily social life at the same time, social attitudes towards the use of the Internet for juveniles show more tolerance, public opinion less use of negative labels to describe teenagers' Internet usage, increasing number of teenagers chose to create and operate a we-media account [2]. While the Internet gives teenagers a broader and more diversified platform to display themselves, it also brings positive and negative impacts on both the minds and lives of underage users and their peer audience, such as cyber-violence, body anxiety, peer pressure, etc. [3]. While adolescence is a special stage of physical and mental development, it is an important period for the formation of self-image; adolescents' psychological activities gradually change from perceiving and exploring the external world to understanding and recognizing themselves, and the contact and communication with online media has become an important mediator for adolescents to perceive the world, which has a significant impact on adolescents' physical and mental development.

3. Theoretical Framework

According to the Social Comparison Theory proposed by psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954, people often assess themselves and others in the areas of attractiveness, wealth, intelligence, and success. Social comparison theory suggests that individuals judge their social and personal worth based on how they compare themselves to others [4]. In upward comparisons, people compare themselves to others who are perceived to be better than them in some way; people are driven by the upward urge to improve themselves in order to outperform the targets used as comparisons [5]. But in doing so, when individuals believe that they are not capable of achieving the same success as the comparison target, upward comparison will also bring greater frustration to people [6]. In downward comparisons, comparisons are made with people who are perceived to be inferior to them; this process may give people confidence but can also become too complacent if not used correctly [7]. Research on motivation in social comparison theory is generally divided into three perspectives: self-evaluation, self-improvement, and self-satisfaction [8]. In the special mental development period of adolescence, minors tend to use many social comparisons to improve their understanding of themselves and the world around them. Meanwhile, related studies have shown that the intensity of adolescents' use of social networking sites is significantly positively correlated with upward social comparison and that both the intensity of social networking site use and upward social comparison are significantly positively correlated with adolescent depression [9]. Based on this theoretical framework, this study investigates the positive and negative impacts that adolescents perceive on their peers' self-mediation, using questionnaires, which have the advantage of collecting data objectively and quickly, objective choices and scale questions are used to collect more objective answers from the participants.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

This study used an online questionnaire as one of the data collection methods, which was distributed to junior and senior high school students under the age of 19, and a total of 109 questionnaires were recovered, all of which were valid responses. Of all the questionnaires recovered, the male-to-female ratio was 51.38% and 48.62%.

The questionnaire was designed with objective questions, subjective questions, and matrix scales. The questionnaire questions were broadly divided into two parts, the first part mainly explored the motivation of the youth group themselves to operate self-media, the type of content of their works, and the positive and negative impacts brought by operating self-media, and cross-analyzed on the basis of the collected data. The second part was designed with questions about the motivations and positive and negative impacts brought by focusing on we-media bloggers who are also teenagers; most of the concerns in the two parts are psychological impacts, such as self-confidence, satisfaction, positive and negative emotions, and self-identity.

3.2. Data Analysis

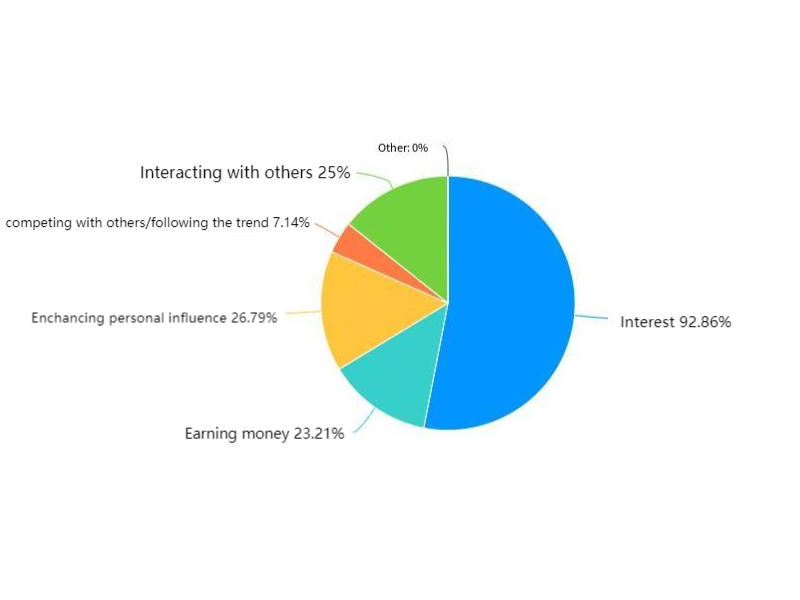

The results of the survey show that 51.38% of the participants who accepted the questionnaire have operated or are operating their own self-media accounts. The motivation for most of the questionnaire surveyed teenagers to run their own media accounts is their own hobbies and interests (92.86%), followed by enhancing their personal influence (26.79%) and communicating and interacting with others (25%); while only a few of participants are motivated by competing with others (7.14%). It indicates that currently operating we-media accounts would not be an important part of peer comparison among adolescents. It is noteworthy that 23.21% of the adolescent participants had operated a we-media account with the purpose of earning income. The specific data is presented as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Motivation for teenagers to run we-media accounts.

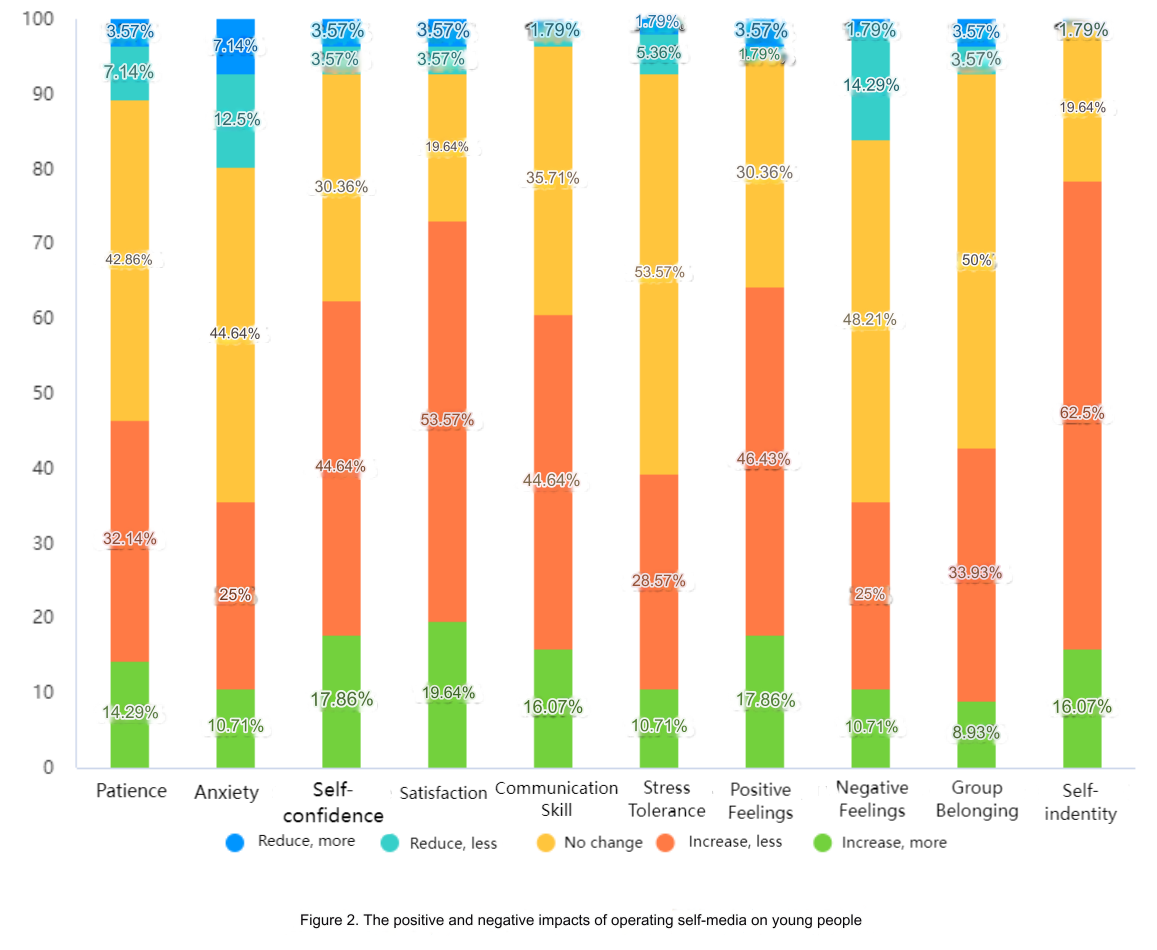

In the question "What positive/negative impacts do you think operating self-media has on you", the data reflects that more participants believe that both the positive and negative impacts have increased than decreased; 78.57% of the participants believe that their sense of self-identity has increased during the process of operating self-media on their own, and about 20% of the participants believe that their self-confidence, satisfaction and positive emotions have increased more during the process. The specific data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The positive and negative impacts of operating self-media on young people.

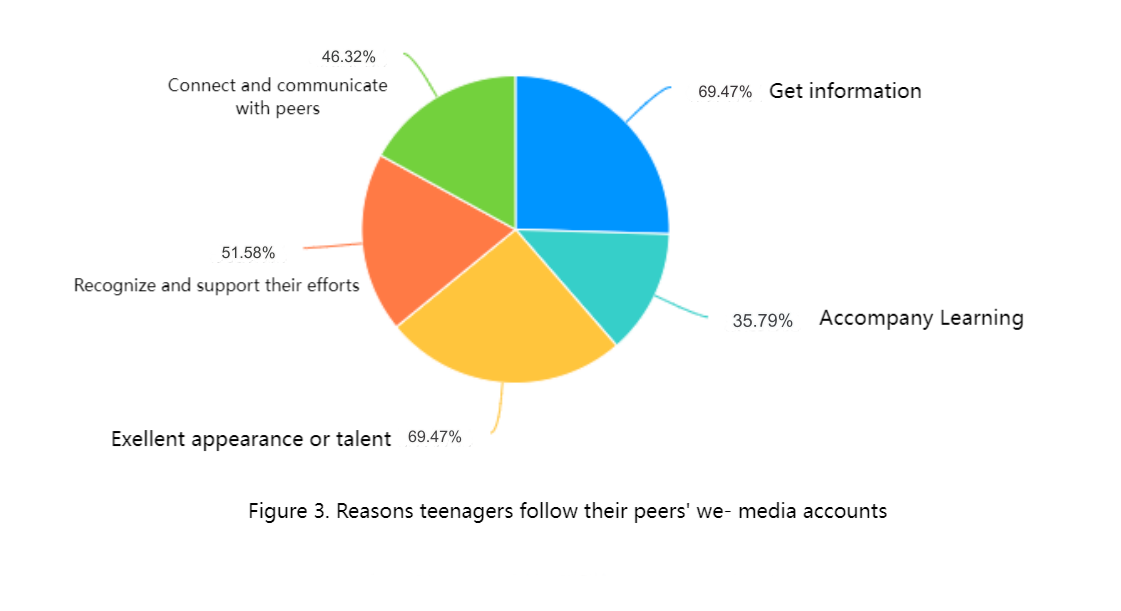

The results showed that 87.16% of the participants had followed or were following teenage we-media bloggers. When participants were asked about the main reasons for following teenage self-media accounts, the most frequently chosen options were 'good appearance or talent' (69.47%) and 'to obtain useful information and knowledge' (69.47%), while only 35.79% of the participants followed teenage accounts for the reason of 'to accompany learning'. Combined with the answer data of the motivation to operate self-media, the most chosen reason is "for hobby"; it can be inferred that when teenagers operate self-media and follow the accounts of their peers, the main reason is to entertain and share hobbies, and the starting point is less to compare or compete. The specific data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Reasons teenagers follow their peers' we-media accounts.

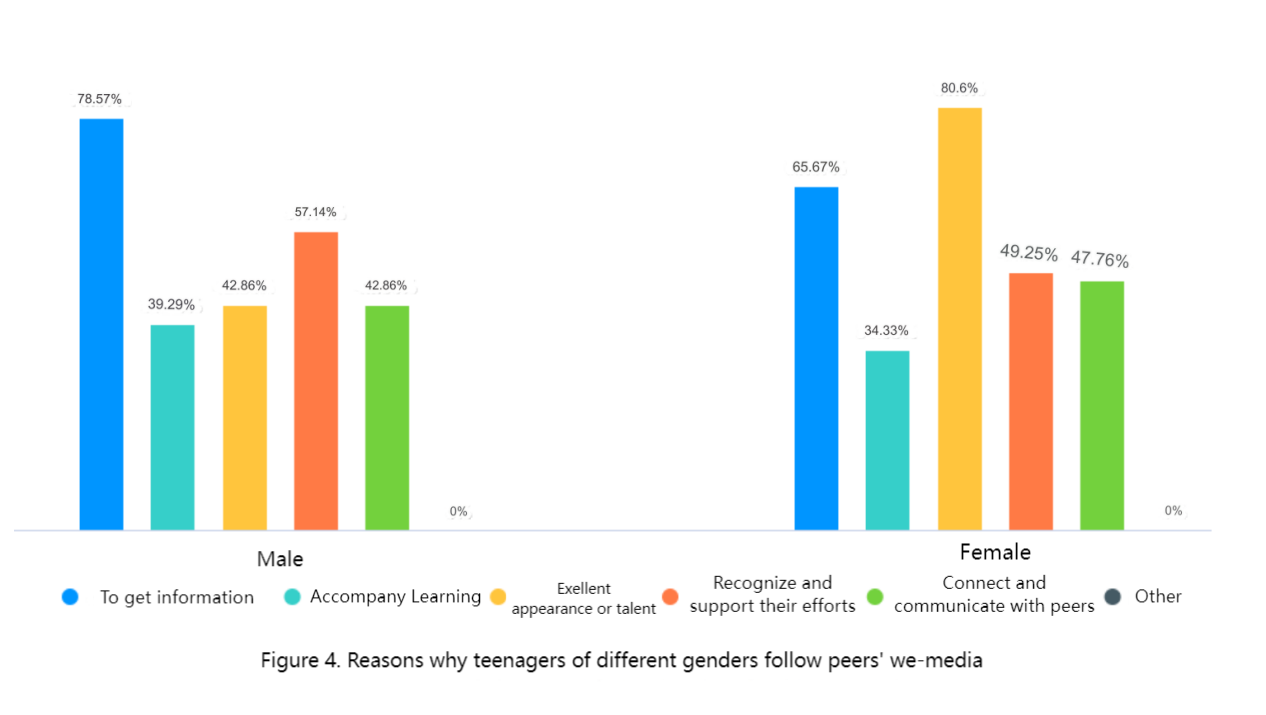

There are obvious gender differences in the reasons for following teenagers' self-media accounts. Teenager females pay more attention to appearance and talent content, while males are more interested in obtaining information. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Reasons why teenagers of different genders follow peers' we-media.

In the question "What positive/negative impacts do you think following teenage bloggers have on you?", more participants believed that both positive and negative impacts have increased. Among them, 48.42% of participants believed that following teenage self-media has increased a small number of positive emotions, more than half (58.95%) of the participants believed that following teenage bloggers increased their peer pressure, but at the same time, about 30% of the participants believed that their self-confidence, satisfaction, collective belonging, and self-identity were improved by following teenage bloggers of the same generation has increased, and more than half of the participants believed that their negative emotions had not changed significantly during this process. The specific data is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The positive and negative effects of following peer teenage bloggers.

According to the reasons why teenagers pay attention to self-media analyzed in the previous article, although the motivation to follow peers' accounts is more entertainment-oriented, teenagers will still feel greater peer pressure when watching the self-expression of teenagers of the same generation.

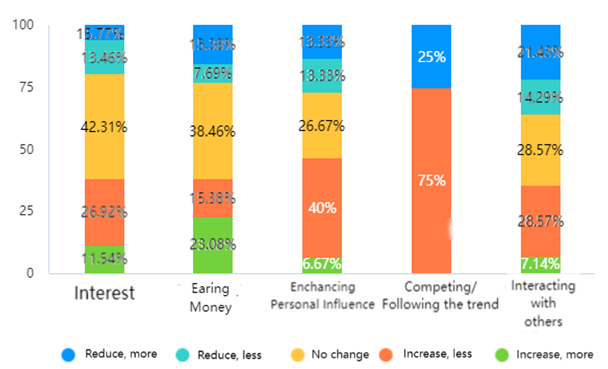

When cross-analyzing the reasons why teenage participants operate self-media and its effects, it was found that participants who operate self-media based on competition with others reported more increases in anxiety. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Changes in anxiety by different motivations of operating we-media accounts.

When asking participants whether they had imitated or learned from the teenage bloggers they followed, only 24.21% of the participants had relevant experiences.

According to collected data, most of these participants chose to learn the blogger's learning methods and application experience, while a small number also chose to imitate the blogger's dressing style and work and rest habits. However, the vast majority of participants believed that learning or imitating the experiences of these bloggers would bring more positive impacts, and only one believed that there was no impact.

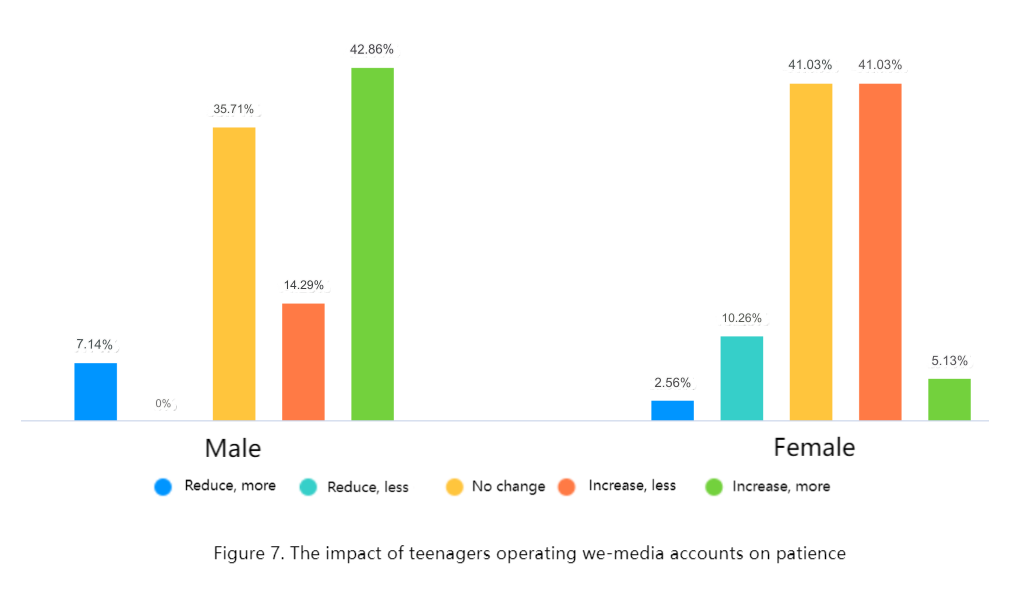

When cross-analyzing the impact of teenagers operating self-media accounts and the gender of teenage participants, there are gender differences in some options.

In terms of patience, a higher proportion of male participants rated their patience as increasing and more, while female participants rated it as less increasing. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: The impact of teenagers operating we-media accounts on patience.

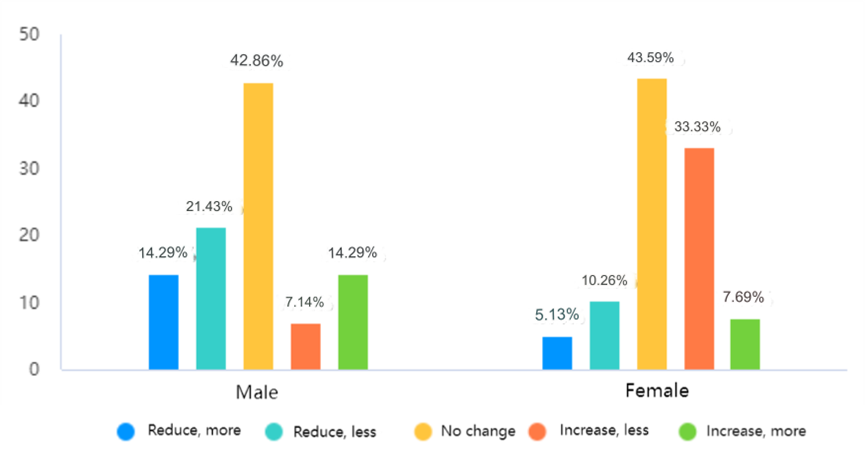

At the same time, in terms of anxiety, a higher proportion of female adolescent participants believe that operating self-media has increased their anxiety, while a higher proportion of male participants believe that operating self-media has reduced their anxiety. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: The impact of teenagers operating we-media accounts on anxiety.

When the impact of following peers' self-media accounts was cross-compared with the gender of adolescent participants, larger gender differences were found in peer pressure and anxiety.

It was found that the proportion of female participants (68.66%) who believed that following their peers' accounts brought more peer pressure to themselves was nearly twice the proportion of male participants (35.71%), while more than half of the male participants believed that following their peers' accounts brought them more peer pressure. There is no change or even decrease after the category account. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: The impact of teenagers following their peers' we-media accounts on peer pressure.

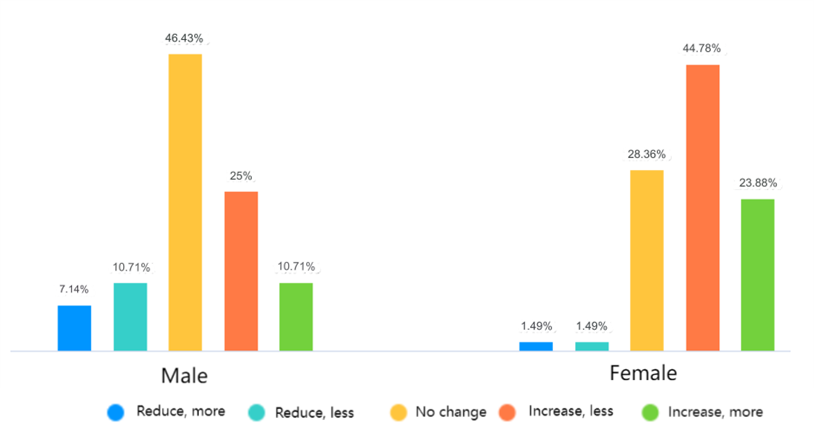

At the same time, it was found that the proportion of female participants (43.29%) who believed that their anxiety increased after following their peers' accounts was 11% higher than the proportion of male participants (32.15%), and compared with women, a higher proportion of male participants believed that their anxiety There has been a decrease in following such accounts. The specific data presentation is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: The impact of teenagers following their peers' self-media accounts on anxiety.

According to the summary analysis of the questionnaire results, at this stage, the driving force for teenagers to operate self-media is more hobbies, and the process of operating self-media brings more positive feedback, such as an increase in self-confidence and self-identity. When following and browsing other teenagers' self-media accounts, although the positive feedback brought about by entertainment increases more, the increased peer pressure cannot be ignored. In terms of gender differences, teenage females reported increased anxiety or peer pressure when operating their own accounts or following and browsing their peers' self-media accounts, while the data from male participants showed the opposite trend. Peer pressure, anxiety, and negative emotions all showed no change or even decrease.

4. Discussion

The study found that teenage girls were more negatively affected than boys when they were exposed to their peers' self-media. This is consistent with what the author has observed in various posts, works, and comment areas on their respective media platforms. For example, on social media platforms and self-media websites, most of the publishers of works discussing body anxiety are female, while there are fewer male publishers. In the comment area under relevant posts, most of the people participating in related discussions are female accounts. Connected with social comparison theory, a possible explanation for this phenomenon is that when operating and browsing self-media, female teenagers tend to compare themselves upward with accounts they think are better, so they feel more anxiety and peer pressure in the process; while male teenagers may make more downward comparisons in this process, that is, compare themselves with accounts they think are inferior, in order to increase their self-confidence and reduce related stress and anxiety. Another explanation is that women are more susceptible to negative emotions than men [10]. Therefore, it may be that when both parties receive similar content, adolescent women will be more aware of their own negative emotions than men, and then answers related to more negative emotions were reflected in the questionnaire.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study are that the motivation of teenagers as a whole to operate self-media versus being a peer viewer is more for entertainment and information acquisition and less for the idea of climbing and competing with peers through this channel. Adolescents' use of we-media can bring them a greater sense of self-identity, increased satisfaction, communication skills, and positive emotions. The data as a whole also reflects an increase in negative feedback, such as peer pressure and anxiety. The study further concluded that minors' self-media accounts can help adolescents' mental development, build self-confidence, enhance self-identity, and improve communication and problem-solving skills; and there is a large gender difference in the effect of following peer self-media on peer pressure. Therefore, while encouraging the operation of youth self-media, the mental health of its operators should not be neglected; psychological education on facing pressure and reasonable comparison are also recommended.

This study provides some references for future research in this direction, mainly on the possibilities of adolescent self-media operation and gender differences, and future research should focus more on the influence of minors' self-media operation on mental development for in-depth investigation.

References

[1]. China Internet Network. (2023) Information Centre The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development.

[2]. Yong, F., Weimin, J., Jie, S., Binyan, Y., Lin, J., Jun, Y. (2023) Annual Report on the Internet Use of Chinese Minors.

[3]. Caixia, S. (2018) Adolescents' Internet Use Types and Psychosocial Adjustment, 12, 18-24.

[4]. Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 72, 117-140.

[5]. Suls, J. M., Wheeler L. (2023) Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research. New York: Plenum Press.

[6]. Lockwood, P., Kunda, Z. (2019) Increasing the Salience of One's Best Self Can Undermine Inspiration by Outstanding Role Models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7, 214-228.

[7]. Miller, R. L. (2017) Social Comparison Process: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publication Service, 1-19.

[8]. Shufen, X., Guoliang, Y. (2015) A Review on Research of Social Comparison. Advances in Psychological Science, 13, 78-84.

[9]. Xiaojun, S., Shuailei, L., Jinfeng, N., Jinglei, Y., Yuantian, T., Zongkui, Z. (2016) Upward Social Comparison in Social Network Site and Depression: Mediating of Social Anxiety. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 32-35.

[10]. Proverbio, A. M., Adorni, R., Zani, A., & Trestianu, L. (2019). Sex Differences in the Brain Response to Affective Scenes with or without Humans. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2374-2388.

Cite this article

Xu,S. (2023). Exploring the Motivation in Adolescents’ Running of We-Media and as Peer Audiences. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,31,51-58.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. China Internet Network. (2023) Information Centre The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development.

[2]. Yong, F., Weimin, J., Jie, S., Binyan, Y., Lin, J., Jun, Y. (2023) Annual Report on the Internet Use of Chinese Minors.

[3]. Caixia, S. (2018) Adolescents' Internet Use Types and Psychosocial Adjustment, 12, 18-24.

[4]. Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 72, 117-140.

[5]. Suls, J. M., Wheeler L. (2023) Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research. New York: Plenum Press.

[6]. Lockwood, P., Kunda, Z. (2019) Increasing the Salience of One's Best Self Can Undermine Inspiration by Outstanding Role Models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7, 214-228.

[7]. Miller, R. L. (2017) Social Comparison Process: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publication Service, 1-19.

[8]. Shufen, X., Guoliang, Y. (2015) A Review on Research of Social Comparison. Advances in Psychological Science, 13, 78-84.

[9]. Xiaojun, S., Shuailei, L., Jinfeng, N., Jinglei, Y., Yuantian, T., Zongkui, Z. (2016) Upward Social Comparison in Social Network Site and Depression: Mediating of Social Anxiety. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 32-35.

[10]. Proverbio, A. M., Adorni, R., Zani, A., & Trestianu, L. (2019). Sex Differences in the Brain Response to Affective Scenes with or without Humans. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2374-2388.