1. Introduction

Negative emotions, especially foreign language anxiety (FLA), have long been active since 1970 [1]. However, positive emotions, such as motivation, persistence, and resiliency, have emerged as important variables for improving learner’s long-term language learning experiences as the rising of positive psychology [2]. Among positive emotions, enjoyment is a trending research topic in foreign language (FL) learning contexts [3]. By combining positive and negative emotions in FL research, a more comprehensive understanding of emotions can be achieved [4]. Botes discovered moderate positive associations between FLE and self-perceived accomplishments, confirming the importance of FLE in SLA and instruction. FLE can also offset the downside of negative emotions [5]. Another crucial contributor to FL learning is motivation. Recently, there has been a discussion about whether learners' emotions can represent intrinsic motivation or simply a general behavioral tendency, and emotion has not been featured prominently in the literature on motivation, especially in SLA[6]. Gardner's integrative motive and Dörnyei's L2 self-system are extensively used models for measuring L2 motivation. Even though these models occupy the obvious position, they still fail to extend to a larger scope of emotions in the L2 domain. Therefore, the expectancy-value motivation scale (used to measure expectancy for success and four other value beliefs) may fully analyze the link between motivational factors and emotions in the FL learning process [7]. The current study sought to investigate the relationships between Chinese university students’ FLE, expectancy-value motivation, and English competence.

2. Research Background

2.1. Foreign Language Enjoyment

The establishment of Positive Psychology represents a significant shift in the research approach from primarily examining negative emotions to including considering positive emotions in the context of L2/FL. This change aims to incorporate a broader spectrum of emotions that are relevant to the development of L2 proficiency. The definition of FLE is described by Dewaele and MacIntyre as a multifaceted feeling that encompasses the combination of facing challenges and feeling capable of overcoming them [3]. Dewaele and MacIntyre developed a 21-item Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (FLES) by collecting web-based questionnaires completed by 1,746 multilingual volunteers to assess FLE [8]. Participants in their study reported more FLE than FLCA in L2 classrooms. Dewaele and MacIntyre then divided the scale into two FLE factors—Private-FLE and Social-FLE [3]. Li et al. included the teacher factor in the original two-factor framework and confirmed its application in the context of Chinese foreign language acquisition [4]. A shortened version of the FLES is required since long questions reduce completion rates. Therefore, in order to balance the effectiveness and efficiency of the measure, Botes et al. further developed a 3-element structure (each containing three 3-items), which was composed of Teacher Appreciation, Personal Enjoyment, and Social Enjoyment [5]. This short-from measure of FLE was found to be valid and reliable and was recommended for studying enjoyment in FL learning.

Based on the definition of FLE, enjoyment can be related to the learning process and the learning outcome and achievement. According to the research, there is a considerable positive correlation between FLE and FL success, and compared to FLCA, FLE is more essential [9]. Besides, enjoyment can predict English achievement more in the study done by Li & We [10]. The improvement of FL proficiency by FLE can be achieved through the following aspects. Firstly, FLE can cultivate an enjoyable learning environment which plays a vital moderating role in promoting FL performance; second, FLE has the potential to enhance the acquisition of FL by promoting heightened attention and consciousness towards the linguistic input and helping learners to deal with problems during the learning process; third, FLE can motivate FL to aim higher [11].

2.2. Expectancy-value Motivation

The expectancy-value theory (EVT) is a contemporary method for studying motivation proposed by Atkinson and developed by Eccles and Wigfield. Differences in learners’ persistence, desire to learn, motivation, and achievement in second language learning may be due to perceptions of their abilities, expected achievement, and values of achieving important tasks which are related to EVT, an approach for scholarly inquiry into motivation [12].

Expectancy and four types of subjective task values are two components of EVT mode (these two components can form a multiplicative function), and they defined expectancies for success as learners' beliefs about their anticipated performance on a forthcoming task (either a current or long one). The expected delight and pleasure that learners receive from anticipating and completing a task is characterized as intrinsic value (or interest value). Utility value, on the other hand, is more concerned with extrinsic motivation and to what extent a work can fit into an individual's goals. Attainment value is an individual's sense of the importance of completing tasks [12]. These three subjective values have been shown to improve learning [13]. In contrast, cost value is what an individual needs to invest in and strives to avoid while anticipating chores or activities. There are three kinds of costs: effort, opportunity cost, and emotional cost [12]. Studies of EVT have set solid groundwork for proving EVT’s predictive effect on L2 behaviors [13]. Trautwein et al. used a questionnaire to tap into the expectancy and value beliefs of 2,508 German students in language and mathematics domains[7]. Researchers looked into the connection between motivation, English competence, and FLE. 280 high school students who were studying English were polled by Dong et al [14]. They discovered that FLE and expected-value beliefs were directly connected. Expectancy beliefs, intrinsic value, personal enjoyment, and anxiety of unpleasant emotions all worked together to predict how proficient the students thought they were, but they did not use actual English test scores to conduct the research [14]. Though it is of great research value to study learning from the perspective of EVT, EVT is still under-researched in the FL domain and the impact of EVT on real-world foreign language performance must be quantified.

In light of the analysis presented above, FLE and EVT each have a favorable predictive impact on proficiency in a foreign language. Since their effects on performance are predictable, it is also necessary to assess their impact on the actual foreign language test. Therefore, the purpose of this study, which targets Chinese university students, is to examine the questions below:

1. What is the status quo of FLE, expectancy-value motivation, and test-measured English competence among Chinese undergraduates?

2. How does FLE affect Chinese university students' expectancy-value motivation?

3. What connection exists between FLE, expectancy-value motivation, and Chinese undergraduates' test-measured English proficiency?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The convenience sampling approach was used via an online questionnaire distributed to 74 Chinese undergraduates (31 males, and 43 females; the average age was 19.84; 45 sophomores, 15 juniors, and 14 seniors). These students are all majoring in subjects other than English, and they all attend a university in southern China. For them, taking an academic English course is needed. The goal of this course is to help students enhance their critical thinking abilities while also enhancing their academic English listening, speaking, reading, and writing abilities. All participants took the College English Test-Band 4 (CET-4), a domestic standardized English examination for college students with a combined score of 720.

3.2. Instruments

In the current investigation, a composite questionnaire with four components was employed. Items concerning participant background, such as gender, age, and grade, made up the first section. The second part measures FLE with Botes et al.’s 9-item short FLE Scale (S-FLES) [5]. Three dimensions, which are FLE-Personal Enjoyment, FLE-Social Enjoyment, and FLE-Teacher Appreciation (each dimension has 3 items). High internal consistency was found by this S-FLES analysis (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.93). Feedback on these questions ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A 16-item scale from the study of Trautwein et al. made up the third section. Expectancy beliefs, attainment value, intrinsic value, utility value, and cost value were the five aspects addressed by the scale [7]. Each item was graded on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagreed and 7 being strongly agree. In this study, the scale exhibits a good level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.899). Then, students provided their CET-4 scores.

3.3. Data Analysis

Using SPSS 27.0, the descriptive statistics of FLE, Expectancy-value motivation, and English competence were studied. The FLES and expectancy-value motivation scales scored 0.855 and 0.817 on Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) tests, respectively, demonstrating the suitability of these scales for information extraction and their high validity. To determine the association between FLE, Expectancy-value motivation, and English proficiency, the Pearson correlation analysis was used. This research employed Amos software to examine the direct impact of FLE dimensions on EVM and the indirect impact on CET-4 scores.

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Levels of FLE, Expectancy-value Motivation and English Proficiency of Chinese Undergraduate EFL Learners

As Table 1 demonstrates, the mean value of the overall level of FLE is 5.491 which is higher than the study done by Dong et al., [14]. The mean CET-4 score is 547.216, indicating they can almost reach the upper intermediate English level. Compared with general College English courses, Academic English courses have more obvious teaching effects.

It shows that Chinese college students have higher FLE than high school students, especially the teacher factor, which has the highest score in these three dimensions. The explanation for this is that college students have more autonomy in learning English than high school English learners (a large part of the English teaching revolves around preparing for the English test of the College Entrance Examination) [14]. Besides, China has entered the information age, and the new English teaching methods and teaching models have been continuously improved. As a result, students' experience of college English learning and their positive emotions have been greatly improved.

Teacher and classroom environment factors are more prominent than the personal enjoyment factors which is consistent with the findings of the research carried out by Dewaele & Dewaele [15]. They argue teachers and peers are more influential on FLE because things happened in the classroom can lead to “ups and downs” in FLE. Teachers, therefore, have the responsibility to moderate the learning emotions. When teachers demonstrate care for their students, understand their emotions, alleviate their stress, and foster their self-assurance, they will achieve better outcomes in their teaching [15].

Among the expectancy-value motivation factors, attainment value and utility value have the highest mean value. The results are in accordance with Dong et al. Attainment value is related to focus on the experience of proficiency and autonomy and utility value emphasis on long-term goals [14][7], meaning that, Chinese undergraduates deem English learning and competence are significantly valuable in the long run, but acquiring the ability and skills comes at a cost.

Table 1: Descriptive Data. | |||||

Items | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Deviation | Median |

FLE-Personal Enjoyment | 1.000 | 7.000 | 5.063 | 1.259 | 5.000 |

FLE-Teacher Appreciation | 3.333 | 7.000 | 5.982 | 0.822 | 6.000 |

FLE-Social Environment | 1.333 | 7.000 | 5.428 | 1.299 | 5.667 |

FLE | 3.000 | 7.000 | 5.491 | 0.987 | 5.444 |

Expectancy Beliefs | 2.250 | 7.000 | 4.912 | 1.269 | 4.750 |

Attainment | 3.333 | 7.000 | 5.752 | 0.915 | 6.000 |

Intrinsic | 1.600 | 7.000 | 4.727 | 1.246 | 4.800 |

Utility | 3.500 | 7.000 | 5.973 | 0.968 | 6.000 |

(negative) Cost | 1.000 | 7.000 | 4.932 | 1.417 | 5.000 |

Expectancy-value Motivation | 3.188 | 7.000 | 5.147 | 0.846 | 5.031 |

CET-4 Score | 434.000 | 647.000 | 547.216 | 46.666 | 553.500 |

4.2. Relationship among FLE and Expectancy-value Motivation of Chinese Undergraduates

Table 2: Matrix of Pearson Correlation (* p<0.05 ** p<0.01).

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

1.FLE-Personal Enjoyment | 1 | ||||||||||

2.FLE-Teacher Appreciation | 0.620** | 1 | |||||||||

3.FLE-Social Environment | 0.639** | 0.674** | 1 | ||||||||

4.FLE | 0.878** | 0.837** | 0.898** | 1 | |||||||

5.Expectancy Beliefs | 0.770** | 0.518** | 0.408** | 0.651** | 1 | ||||||

6.Attainment | 0.672** | 0.532** | 0.453** | 0.632** | 0.518** | 1 | |||||

7.Intrinsic | 0.709** | 0.502** | 0.675** | 0.737** | 0.513** | 0.660** | 1 | ||||

8.Utility | 0.447** | 0.410** | 0.329** | 0.448** | 0.284* | 0.649** | 0.472** | 1 | |||

9.Cost | -0.104 | -0.011 | 0.030 | -0.034 | -0.198 | 0.133 | 0.199 | 0.256* | 1 | ||

10.Expectancy-value Motivation | 0.793** | 0.589** | 0.608** | 0.768** | 0.715** | 0.821** | 0.895** | 0.651** | 0.290* | 1 | |

11.CET-4 score | 0.434** | 0.203 | 0.223 | 0.339** | 0.432** | 0.216 | 0.155 | 0.118 | -0.279* | 0.235* | 1 |

In Table 2, Pearson correlation analysis is used to explore the connection between FLE and expectancy-value motivation, indicating a substantial positive connection (with a value of 0.768 which is above 0, p<0.01) between these two factors (except the cost value). with expectancy-value motivation. As a result, FLE increases along with expectation beliefs, attainment value, intrinsic value, and utility value[6]. Positive emotions influence learners' behaviors and attitudes in the process of learning a FL, igniting their drive and providing fuel.

To be more specific, FLE has the most significant positive relationship with intrinsic value and expectancy beliefs. Loh argues that high intrinsic value of students may have more enjoyment engaging in academic activities because of self-control which is deemed to be a core requirement of success academically, which means the more enjoyable they are, the more engaged and more successful, forming a positive loop [13].

All FLE dimensions correlate with expectancy-value motivation as a whole. Especially, personal enjoyment has the most significant positive relationship with expectancy-value motivation. As mentioned above, university students have more autonomy in learning and pay more attention to their self-feeling. Therefore, the more they enjoy learning, the stronger motivation they have and the higher expectancy of success.

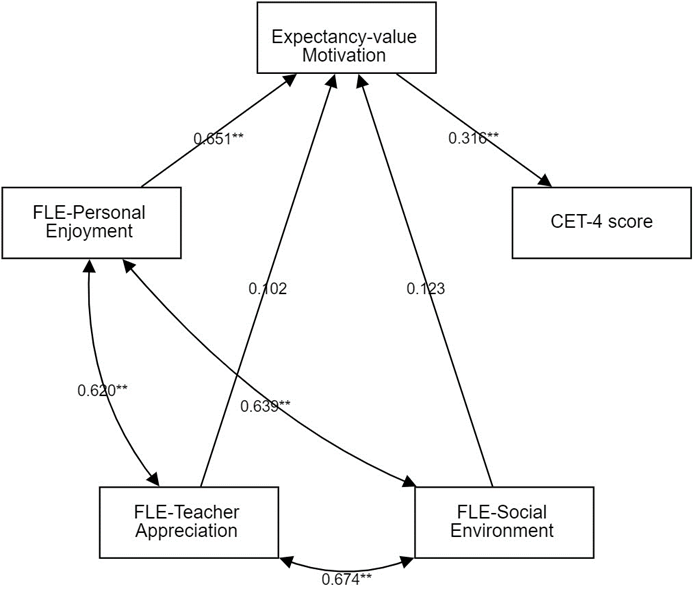

4.3. Direct Effect of FLE on Expectancy-value Motivation and Indirect Effect

FLE and expectancy-value motivation are strongly positively connected with both the CET-4 score, as seen in Table 2. The results resonate with previous studies, such as Dewaele & Alfawzan, Li & Wei [9][10]. However, CET-4 scores have weak relationship with the teacher and social environment variables in FLE and weak relationship with intrinsic and utility values in expectancy-value motivation. As the data obtained using Amos path analysis showed (figure 1), of the three parameters of FLE, only personal enjoyment directly affects expectancy-value motivation and indirectly on CET-4 scores, with p< 0.01 indicating significantly related. At most colleges and universities, non-English majors need to take about two to four English classes a week. Students need to study English by themselves in the spare time, which highlights the personal influence on learning a foreign language. If students can devote themselves to English learning activities (and enjoy this process) during the free time after class, such as listening to English programs, watching English videos, etc., their English level will be greatly improved. The increased requirement of autonomous learning urges students to have strong expectancy beliefs because this factor requires students' self-restraint and self-management. This can explain why personal enjoyment and expectancy beliefs have a significant impact on English proficiency.

Figure 1: Amos Analysis of direct and indirect effect of FLE variables (** p<0.01).

5. Conclusion

This study looked into the general profile of FLE, expectancy-value motivation, and English proficiency of Chinese undergraduates and the relationship among these variables. Students have medium to high levels of FLE, especially enjoyed the most related to the teacher factors. They hold strong utility and attainment values because of the practical reasons that English is vital to their future further study and joy-seeking. All value components (except cost value) and the expectation beliefs of Chinese students were highly correlated with FLE. The personal enjoyment influences expectancy-value motivation directly and CET-4 scores indirectly. This result has certain inspirations for practical implications. First, teachers and schools can provide students with more personal learning environments and help. For example, they can set up some independent foreign language learning centers or give students more independent learning guides. In addition, teachers can give students more support and encouragement to create a better learning atmosphere and give more guidance when working on group tasks. The study content can involve more topics that students find valuable and useful in real life, which can encourage more interest in foreign language learning, and allow them to apply their foreign language knowledge in practice.

This study also has some limitations. It only used quantitative research, so incorporating qualitative research is feasible for the future study (such as classroom observations, and interviews which will provide a deeper understanding of the student's situation). Future researches can also combine different teaching methods to understand the impact of different pedagogies on FLE and motivation. In addition, this study only used a random sample from one university. China is a large country, and students' levels of English proficiency range according to location. There hasn't been enough study done on how different foreign language proficiency levels affect FLE and expectancy-value motivation. Despite its drawbacks, this study contributes further empirical data to the body of knowledge regarding the connection between FLE, expectancy-value motivation, and English competence.

References

[1]. Dewaele, J. M., Witney, J., Saito, K., & Dewaele, L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 676–697.

[2]. Mercer, S., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 153–172.

[3]. Dewaele, J. M., & Macintyre, P. D. (2016). Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety: The Right and Left Feet of the Language Learner. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive Psychology in SLA (Issue April, pp. 215–236). Multilingual Matters.

[4]. Li, C., Jiang, G., & Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ Foreign Language Enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment scale. System, 76, 183–196.

[5]. Botes, E., Dewaele, J. M., & Greiff, S. (2021). The development and validation of the short form of the foreign language enjoyment scale. The Modern Language Journal, 105(4), 858-876.

[6]. Dewaele, J.M., Botes, E., & Meftah, R. (2023). A Three-Body Problem: The effects of foreign language anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom on academic achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 1–16.

[7]. Trautwein, U., Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Lüdtke, O., Nagy, G., & Jonkmann, K. (2012). Probing for the multiplicative term in modern expectancy-value theory: A latent interaction modeling study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 763–777.

[8]. Dewaele, J.M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237–274.

[9]. Dewaele, J. M., & Alfawzan, M. (2018). Does the effect of enjoyment outweigh that of anxiety in foreign language performance? Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 21–45.

[10]. Li, C., & Wei, L. (2023). Anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom in language learning amongst junior secondary students in rural China: How do they contribute to L2 achievement? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(1), 93–108.

[11]. Jiang, G., Li, C., & Dewaele, J. M. (2020). The complex relationship between classroom emotions and EFL achievement in China. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(3), 485–510.

[12]. Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary educational psychology, 61, 101859.

[13]. Loh, E. K. Y. (2019). What we know about expectancy-value theory, and how it helps to design a sustained motivating learning environment. System, 86, 1–27.

[14]. Dong, L., Liu, M., & Yang, F. (2022). The Relationship Between Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety, Enjoyment, and Expectancy-Value Motivation and Their Predictive Effects on Chinese High School Students’ Self-Rated Foreign Language Proficiency. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

[15]. Dewaele, J. M., & Dewaele, L. (2020). Are foreign language learners’ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learners’ classroom emotions. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 45–65.

Cite this article

Li,X. (2023). Exploring the Direct Effect of Foreign Language Enjoyment on Expectancy-value Motivation and Indirect Effect on English Competence. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,31,1-8.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Dewaele, J. M., Witney, J., Saito, K., & Dewaele, L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 676–697.

[2]. Mercer, S., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 153–172.

[3]. Dewaele, J. M., & Macintyre, P. D. (2016). Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety: The Right and Left Feet of the Language Learner. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive Psychology in SLA (Issue April, pp. 215–236). Multilingual Matters.

[4]. Li, C., Jiang, G., & Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ Foreign Language Enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment scale. System, 76, 183–196.

[5]. Botes, E., Dewaele, J. M., & Greiff, S. (2021). The development and validation of the short form of the foreign language enjoyment scale. The Modern Language Journal, 105(4), 858-876.

[6]. Dewaele, J.M., Botes, E., & Meftah, R. (2023). A Three-Body Problem: The effects of foreign language anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom on academic achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 1–16.

[7]. Trautwein, U., Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Lüdtke, O., Nagy, G., & Jonkmann, K. (2012). Probing for the multiplicative term in modern expectancy-value theory: A latent interaction modeling study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 763–777.

[8]. Dewaele, J.M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237–274.

[9]. Dewaele, J. M., & Alfawzan, M. (2018). Does the effect of enjoyment outweigh that of anxiety in foreign language performance? Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 21–45.

[10]. Li, C., & Wei, L. (2023). Anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom in language learning amongst junior secondary students in rural China: How do they contribute to L2 achievement? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(1), 93–108.

[11]. Jiang, G., Li, C., & Dewaele, J. M. (2020). The complex relationship between classroom emotions and EFL achievement in China. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(3), 485–510.

[12]. Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary educational psychology, 61, 101859.

[13]. Loh, E. K. Y. (2019). What we know about expectancy-value theory, and how it helps to design a sustained motivating learning environment. System, 86, 1–27.

[14]. Dong, L., Liu, M., & Yang, F. (2022). The Relationship Between Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety, Enjoyment, and Expectancy-Value Motivation and Their Predictive Effects on Chinese High School Students’ Self-Rated Foreign Language Proficiency. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

[15]. Dewaele, J. M., & Dewaele, L. (2020). Are foreign language learners’ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learners’ classroom emotions. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 45–65.