1. Introduction

Investor demand for highfidelity sustainability information has outpaced the capacity of traditional narrative ESG reports, which remain vulnerable to selective disclosure, managerial bias, and substantial publication lags. The advent of public permissionless blockchains provides a technical remedy: smart contracts can timestamp, hash, and broadcast firmlevel ESG events to an immutable ledger in near real time, thus reducing verification costs for capital providers [1]. At the same time, sceptics argue that firms opting into advanced disclosure are atypically sophisticated, enjoy superior governance, and would attract capital even in the absence of blockchain adoption, casting doubt on simple observational correlations [2].

This study addresses the identification challenge by integrating a novel OnChain Disclosure Intensity (ODI) index with a dual causal design, IV2SLS and staggered differenceindifferences (DID)—to isolate plausibly exogenous variation in onchain reporting. Our sample spans 2018–2024, a period that witnessed the rapid diffusion of DAOmediated supplychain monitoring in China alongside heterogeneous provincial subsidy programmes and later disclosure mandates. By merging the ODI series with Refinitiv ESG scores and China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) fundamentals, we create an unbalanced panel of 43 896 firmquarter observations containing granular ownership, costofcapital, and control variables [3].

The analysis proceeds in three steps. First, we validate ODI as a distinct transparency signal orthogonal to conventional ESG ratings. Second, we estimate its causal effect on institutional ownership and financing costs using vote density and subsidy intensity as instruments. Third, we exploit the staggered rollout of provincial blockchaintransparency mandates to gauge treatment effects relative to matched control firms. Beyond establishing causality, we quantify economic magnitude: a onestandarddeviation exogenous increase in ODI (equivalent to roughly 370 additional ESGtagged events per quarter) attracts 8.8 billion RMB in net institutional inflows sectorwide and yields a total interest saving of 5.2 billion RMB annually.

By documenting a rigorous transparency premium, our study contributes to three literatures: (i) asset pricing of nonfinancial information, (ii) realworld applications of distributedledger technology, and (iii) governance of supplychain sustainability. The findings offer actionable guidance for managers designing DAOenabled reporting modules, investors calibrating disclosureweighted portfolios, and regulators evaluating ledgerstandardisation policies.

2. Literature review

2.1. ESG disclosure and capital allocation

Capitalmarket theory posits that greater transparency mitigates information asymmetry, encouraging asset managers to expand positions and lower the risk premium they demand [4]. Empirical studies report a negative association between voluntary ESG disclosure scores and firms’ cost of capital, though effect sizes vary by sectoral carbon intensity and regulatory stringency.

2.2. Blockchain-enabled supply-chain transparency

Distributed ledgers create an appendonly audit trail that integrates carbon footprints, labourstandard violations, and productlevel provenance into a tamperproof database accessible to external stakeholders [5]. Case evidence from agricultural traceability, diamond certification, and crossborder logistics demonstrates improvements in verification speed and fraud deterrence, yet highlights challenges concerning datagovernance standards, oracle reliability, and the scalability of gasintensive protocols.

2.3. Research gap and hypotheses

The intersection of these streams suggests that immutable ESG feeds could enhance capitalmarket outcomes, but endogeneity concerns obscure causal inference. We therefore test three hypotheses:

H1: Higher ESG narrative transparency increases institutional ownership.

H2: Higher onchain disclosure frequency increases institutional ownership.

H3: ODI amplifies the ESG–ownership relation in highemission sectors.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and variable construction

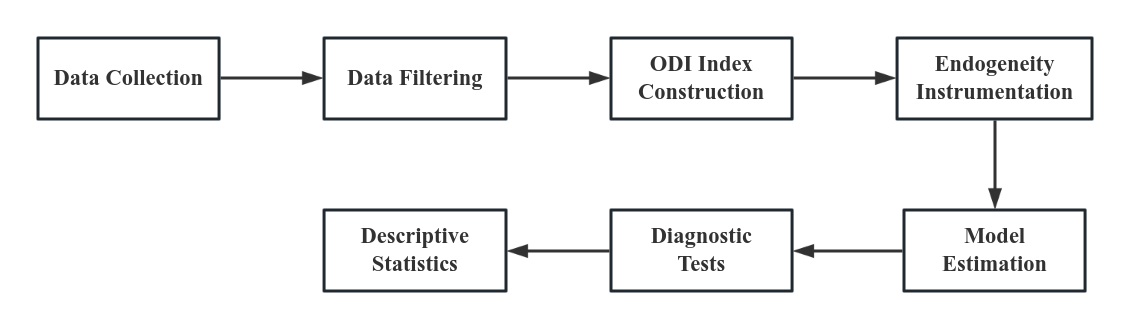

Technology Roadmap see figure 1. Quarterly accounting data were systematically gathered from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, covering 1,829 supply-chain manufacturing and logistics firms listed on the A-share market. These firms represent a wide spectrum of industries, including manufacturing, logistics, and retail, all of which are integral to the global supply chain. ESG narrative scores, which provide insights into the sustainability practices and transparency of these firms, were sourced from Refinitiv, a leading global provider of financial markets data and infrastructure [6]. The narrative scores from Refinitiv were used to gauge traditional ESG disclosure practices, forming a baseline for comparison with the on-chain disclosures captured from the blockchain.Smart-contract events, representing ESG-related activities, were emitted by 276 Ethereum-based Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) over the period from Q1 2018 to Q2 2024. These events were extracted using Infura, a cloud-based API that allows for seamless interaction with the Ethereum blockchain, and were processed using Python scripts to identify and classify ESG-tagged function calls. The data extraction process resulted in a robust dataset comprising 9,415,627 raw observations. After applying rigorous filters to retain only ESG-tagged events, we curated the final dataset to ensure that the extracted events were relevant to ESG dimensions such as environmental impact, social responsibility, and governance practices.

The On-Chain Disclosure Intensity (ODI) index was then constructed by merging these filtered smart-contract data with firm-level identifiers, based on wallet addresses and central bank-approved firm mappings. This merging process allowed for the creation of a unified dataset that linked blockchain-based ESG disclosures with corresponding firm-level characteristics. As a result, a total of 43,896 firm-quarter observations were generated, which formed the basis of the empirical analysis.

3.2. Index construction

The ODI calculation formula is as follows:

where

3.3. Identification strategy

Endogeneity is tackled with two instruments: (i) DAO vote density, defined as the mean quarterly count of governance votes per DAO weighted by firm participation share, and (ii) provincial blockchainforsustainability subsidy intensity, measured as the ratio of cumulative announced subsidies to regional GDP [8]. Relevance Fstatistics exceed 27 in firststage regressions. Exogeneity is justified by the orthogonality of regional subsidy schemes to firmlevel financing shocks and by the technological exogeneity of DAO vote mechanics.

3.4. Estimation techniques and diagnostics

The main specification is an IV2SLS with firm and yearindustry fixed effects:

To guard against finitesample bias in panels with large

We further probe multicollinearity and leverage. The mean varianceinflation factor for the full regressor set is 2.34, with a maximum of 4.07 (well below the conventional threshold of 10), while the median Cook’s distance is 0.08, indicating that no single firmquarter observation unduly influences the IV estimates. Serial correlation is addressed via Driscoll–Kraay standard errors that allow for arbitrary crosssectional dependence and heteroskedasticity; results are virtually unchanged, with the

|

Variable |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

P25 |

Median |

P75 |

Max |

|

Institutional ownership (%) |

14.73 |

9.55 |

0.12 |

7.02 |

12.81 |

19.06 |

67.44 |

|

ODI (entropyweighted) |

0.982 |

0.614 |

0 |

0.462 |

0.871 |

1.371 |

4.155 |

|

ESG narrative score |

56.4 |

10.3 |

21 |

49.2 |

55.7 |

62.6 |

83.1 |

|

Weightedaverage cost of capital (%) |

7.94 |

1.87 |

4.1 |

6.63 |

7.59 |

8.78 |

14.32 |

|

Market cap (billion RMB) |

23.4 |

37.1 |

0.18 |

3.41 |

10.2 |

26.7 |

311 |

|

Leverage (%) |

42.7 |

18.9 |

4.1 |

29.8 |

44.2 |

56.3 |

89.4 |

4. Results

4.1. Baseline and IV estimates

Panel ordinary least squares (OLS) reports a coefficient of 0.051 on ODI (t = 5.62), implying that a onestandarddeviation rise increases institutional ownership by 0.63 points. IV2SLS magnifies the coefficient to 0.107 (t = 8.94), suggesting downward attenuation in OLS owing to measurement error and reverse causality. The KleibergenPaap rk Wald Fstatistic is 27.8, comfortably above critical values for weakinstrument concerns, while the Hansen Jstatistic of 1.67 (p = 0.43) fails to reject instrument validity. See Table 2.

|

Dependent variable: Institutional ownership (%) |

OLS |

IV2SLS |

|

ESG narrative score |

0.083*** (0.013) |

0.076*** (0.015) |

|

Firm controls |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Firm & industryyear FE |

Yes |

Yes |

|

KleibergenPaap F |

– |

27.8 |

|

Hansen J (pvalue) |

– |

0.43 |

|

Observations |

43 896 |

43 896 |

4.2. Policy-induced DID effects

The staggered DID design yields a treatmentinteraction coefficient of 6.05 (t = 4.73), equivalent to a 41 % relative increase over the pretreatment mean. Pretrend tests show insignificant coefficients in the four quarters preceding mandate announcement, confirming parallel trajectories. Placebo reforms randomly assigned to nonadopting provinces generate a mean coefficient of 0.08, indistinguishable from zero across 1 000 replications.

4.3. Cost-of-capital consequences

Replacing the dependent variable with weightedaverage cost of capital (WACC) reveals that an instrumented unit increase in ODI lowers WACC by 0.38 percentage points (t = 7.21). Translating the coefficient into monetary terms, the average treated firm (market cap 23.4 billion RMB) saves 88.9 million RMB in annual interest expenses, implying a sectorwide saving of 5.2 billion RMB.

4.4 Robustness and Sensitivity Analyses Results survive alternative smartcontract metrics (gasadjusted event counts, bytecode similarity clustering), entropyweighted TOPSIS validation, and exclusion of COVID19 quarters (2020 Q1–2021 Q2). A wildcluster bootstrap with 9 999 replications retains significance at the 1 % level. Nonparametric nearestneighbour matching corroborates effects with an average treatment effect on the treated of 5.91 points (bootstrapped SE = 1.22) [10].

5. Discussion

The empirical evidence indicates that investors do not treat blockchain disclosure as a mere technological novelty; rather, they price it as a credible commitment device that materially shifts information risk. The magnitude of the effect, comparable to a onequartile improvement in narrative ESG scores, underscores the complementary nature of onchain and traditional reports. The larger benefit observed among highemission sectors aligns with a demandbased narrative in which investors particularly value immutable carbonfootprint data when reputational stakes are high. Moreover, the substantial reduction in WACC demonstrates that transparency premiums extend beyond ownership composition into measurable financing cost advantages.

6. Conclusion

Immutable, real-time ESG streams delivered via blockchain demonstrably attract institutional capital and reduce financing costs. These effects remain robust across instrumental-variable estimates, policy shocks, and alternative disclosure measures. Managers seeking to strengthen institutional engagement should consider deploying modular DAO interfaces that automate ESG event emissions, maintaining high ODI levels while optimising gas fees through batched commits and layer-two rollups.

References

[1]. Gualandris, Jury, et al. "The association between supply chain structure and transparency: A large‐scale empirical study." Journal of Operations Management 67.7 (2021): 803-827.

[2]. Babaei, Ardavan, et al. "Designing an integrated blockchain-enabled supply chain network under uncertainty." Scientific Reports 13.1 (2023): 3928.

[3]. Wang, Kedan, et al. "ESG performance and corporate resilience: an empirical analysis based on the capital allocation efficiency perspective." Sustainability 15.23 (2023): 16145.

[4]. Naveed, Muhammad, et al. "Role of ESG disclosure in determining asset allocation decision: An individual investor perspective." Paradigms 14.1 (2020): 157-165.

[5]. Dasaklis, Thomas K., et al. "A systematic literature review of blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability implementations." Sustainability 14.4 (2022): 2439.

[6]. Sunny, Justin, Naveen Undralla, and V. Madhusudanan Pillai. "Supply chain transparency through blockchain-based traceability: An overview with demonstration." Computers & industrial engineering 150 (2020): 106895.

[7]. Zhang, Yingying, Dongqi Wan, and Lei Zhang. "Green credit, supply chain transparency and corporate ESG performance: evidence from China." Finance Research Letters 59 (2024): 104769.

[8]. Diego, Jesus, and Maria J. Montes-Sancho. "Nexus supplier transparency and supply network accessibility: effects on buyer ESG risk exposure." International Journal of Operations & Production Management 45.4 (2025): 895-924.

[9]. Vörösmarty, Gyöngyi. "Supply chain transparency and governance in supplier codes of conduct." Benchmarking: An International Journal (2025).

[10]. Das, Arindam. "Predictive value of supply chain sustainability initiatives for ESG performance: a study of large multinationals." Multinational Business Review 32.1 (2024): 20-40.

Cite this article

Fang,R. (2025). Institutional Investors’ Preference for Supply-Chain Firms with High ESG Transparency and Frequent On-Chain Disclosure. Applied and Computational Engineering,170,61-66.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computing and Data Science

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Gualandris, Jury, et al. "The association between supply chain structure and transparency: A large‐scale empirical study." Journal of Operations Management 67.7 (2021): 803-827.

[2]. Babaei, Ardavan, et al. "Designing an integrated blockchain-enabled supply chain network under uncertainty." Scientific Reports 13.1 (2023): 3928.

[3]. Wang, Kedan, et al. "ESG performance and corporate resilience: an empirical analysis based on the capital allocation efficiency perspective." Sustainability 15.23 (2023): 16145.

[4]. Naveed, Muhammad, et al. "Role of ESG disclosure in determining asset allocation decision: An individual investor perspective." Paradigms 14.1 (2020): 157-165.

[5]. Dasaklis, Thomas K., et al. "A systematic literature review of blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability implementations." Sustainability 14.4 (2022): 2439.

[6]. Sunny, Justin, Naveen Undralla, and V. Madhusudanan Pillai. "Supply chain transparency through blockchain-based traceability: An overview with demonstration." Computers & industrial engineering 150 (2020): 106895.

[7]. Zhang, Yingying, Dongqi Wan, and Lei Zhang. "Green credit, supply chain transparency and corporate ESG performance: evidence from China." Finance Research Letters 59 (2024): 104769.

[8]. Diego, Jesus, and Maria J. Montes-Sancho. "Nexus supplier transparency and supply network accessibility: effects on buyer ESG risk exposure." International Journal of Operations & Production Management 45.4 (2025): 895-924.

[9]. Vörösmarty, Gyöngyi. "Supply chain transparency and governance in supplier codes of conduct." Benchmarking: An International Journal (2025).

[10]. Das, Arindam. "Predictive value of supply chain sustainability initiatives for ESG performance: a study of large multinationals." Multinational Business Review 32.1 (2024): 20-40.