1. Introduction

In learning a foreign language as L2, certain western studies found that L1 transfer is a ubiquitous condition during that process. L1 transfer can be deemed as a form of impact of L1 habits on second language learning [1]. Indeed, there are many influence aspects in the L1 transfer, such as grammar, word order, phonetics, and so on. The former western research has already revealed some problem caused by L1 transfer; for Spanish student, it is a substitution that frequently happens when they are learning English pronunciation; they are prone to replace the unknown English word with the equivalent in Spanish [2]. For the native French speaker, there are two aspects of orthographic processing skills when learning English: word-specific knowledge and sensitivity to sub-lexical regularities [3]. According to these studies, it is clearly illustrated that L1 transfer may influence second language acquisition in many aspects. Thus, the L1 transfer can be deemed a significant factor during the process of SLA.

Besides the language transfer study of western countries, it is also a common phenomenon among Chinese EFL learners. Since mandarin and English can be categorized into two different language systems, it would be hard for a mandarin speaker to alter their speaking habits. They thought the negative transfer happened when the native English speaker studied Chinese as their second language because their mother tongue is categorized into non-tonal language and Chinese, a tonal language, in which different tones in the same word may have different meanings [4]. This research is mainly based on the theory of language transfer, which refers to speakers or writers who study a second language by applying knowledge from their native language. For now, the problem of negative transfer of Chinese EFL learners is much more serious because instead of the difference in language, the difference in culture also plays a significant role during such a process. There are tons of articles which discuss how Chinese dialect, Beijing accent, Sichuan accent, or Cantonese, affect English pronunciation. There are, however, varieties of dialects or tones in China, which may lead to different problems when they study English as a second language, especially in pronunciation. The analysis of Liaoning’s accent is rarely discussed for now. Unlike Cantonese, which is hard to master /ʒ/ because there are no such equivalent sounds in the pronunciation system of cantonese [5]. In the southwestern region of China, the Sichuan dialect can be a typical example. When pronouncing alveolar nasal sound, such as /an/, /en/, /in/, or velar nasal sound, such as /ang/ /eng/ /ing/ in Chinese pinyin, the native Sichuan dialect speaker always perform bad. And by negative transfer in language, this problem can also be found when Sichuan EFL learners speak English, especially if there are similar sounds in certain English words [6]. What’s more, for native Cantonese, some think that, for Chinese English-as-Second-Language children, syllable awareness is seldom an important predictor when they do English reading’ [7]. Although there is lot of studies that were directed to identifying how accent impacts English learning, there is a lack of research on how the certain northeastern accent of China, especially the Liaoning accent, shows their influence.

In the whole range of English learning, especially for those Chines EFL learners, the school teaching of English pronunciation course is still seriously ignored in the English language learning [8]. Indeed, we have to admit that there are few chances for learners to practice spoken English in a particular environment. Thus, they often do well in composition and comprehension but worse in listening and speaking.

The main novelty of this work is analyzing the impact of the Chinese accent during process of SLA, and taking the accent of Liaoning province, which has rarely been discussed in past research, as an example. Stress, as one of the critical suprasegmentals in the English pronunciation system, plays a pivotal role in enhancing the comprehensibility of listening and speaking. [9], Chinese learners of English in Liaoning province have a unique stress system in saying, and it always transfers into their pronunciation of English which derives the very misplace of stress in spoken English.

In the results, they are divided into two parts: the segmental factors and the suprasegmental factors. For the segmental aspect, Liaoning accent speakers always confuse /o/ and / ə/ when they pronounce certain words and phrases. They also perform worse in plosive such as /t/, /k/, /p/, and so on, especially when the plosive is located at the end of a phrase or sentence. Based on this feature, the Liaoning accent speaker may have trouble in the usage of connected speech skills. Retroflex consonant is the other difficulty that the Liaoning accent EFL learners are facing. Their pronunciation of the word ‘world’ is the most typical example. For suprasegmentals, they have a unique tone when speaking, which also has a negative transfer during their learning of English as a second language. They are prone to use indicative moods when communicating with others; the tone is lower than in other accents in China. Furthermore, in Liaoning English class, students have no correct teaching in pronunciation while learning a second language.

During the process of second language acquisition, there is a specific negative transfer of L1 to L2 in pronunciation, which is the so-called ‘foreign accent.’ Also, in particular research, the authors thought that the pronunciation of some speakers of L2 indicated a transfer of L1 accent and intonation [10]. Also, Mandarin is a tonal language; hence the different pitch contours over the same syllable can discriminate word meaning [11]; it also happened in the accent and dialect in China. The primary goal of the study is to examine what Liaoning accent affects SLA and how it effects the acquisition of English tone and pronunciation.

However, in some other accents, such awareness may strongly influence learners’ studies during the process of SLA. Northeastern accent, especially Liaoning accent, in China may be more approach to mandarin because people who speak this accent have no problem in distinguishing /n/ and /l/, as well as /n/ and /ŋ/, which may make their learning easier than other areas. The same factors that have impact on learning English for them are more inclined to the aspects of suprasegmentals. Hence, despite Cantonese or other dialects, this author decided to analyze how the Liaoning accent of China affects English pronunciation.

All in all, we can find so much research on this field, but no comprehensive and systematic knowledge has been established. Hence, this article took the method of questionnaire to examine the negative transfer of the Liaoning accent.

2. Methodology

For the study, this author used mixed methods: both quantitative research methods and qualitative research methods. This questionnaire was designed to acquire approximately how Chinese EFL learners think their mother tongue accent impact the way they pronounce English, and the interview questions are designed to have a deep analysis of the interviewees’ Chinese-style English pronunciation. For this study, this author analyzed the data collected from 126 participants, who answered the questionnaire and four interviewees for the brief interviews, which contained some questions about individual basic information and some about their English learning condition. For analyzing the record of their answers, the voice recording was updated to praat and showed the graphs of each piece of voice document. There are 21 questions in the questionnaire. Question 1 to 6 is about basic information; 7 to 14 are designed to identify the speaking environment around the participants; while 15 to 21 is to acquire their own opinions on the pronunciation. To analyze the data, the author made some bar charts to give an overview.

3. Results and Discussion

The Liaoning dialect is more likely to be rhotic, the voice messages received from 6 different persons of different gender and age both embody the feature mentioned above, such as ‘word’ and ‘world.’ According to the interview recording, the three interviewees both have such problems when reading English sentences. They performed well in reading word like ‘hard,’ and ‘enter,’ but sometimes they are more likely to add some rhotic sound in some words; for example, when the interviewee said ‘was,’ their pronunciation sounded more like /wərz/. This result is similar to the former article, which thought that Liaoning people tend to add a /r/ sound after every /ə/ and /ʌ/ sound in every word [12]; hence their pronunciation may confuse the native speaker when speaking to certain /ə/ words. There is the other condition caused by this factor. For the learners in this province, they can not only pronounce /ʊə/ as /ə/, such as the pronunciation of ‘mushroom’ and ‘what’ in Chinese, but also have this phenomenon transferred into the process of speaking English.

According to the record of the interview, it is found that the people who speak Liaoning accent have a high speed of pronunciation, and they are kind of lazy to pronounce ultimately when they are pronouncing vowels. For example, they rarely tell the difference between /i/ and the Chinese character ‘one.’ What’s more, some Chinese EFL learners who pronounce with a Liaoning accent have trouble in pronouncing diphthongs. Lacking awareness in sliding one vowel to the other, many are not able to distinguish /əʊ/ and the Chinese character ‘Oh’, which is pronounced almost the same as ‘Oh.’

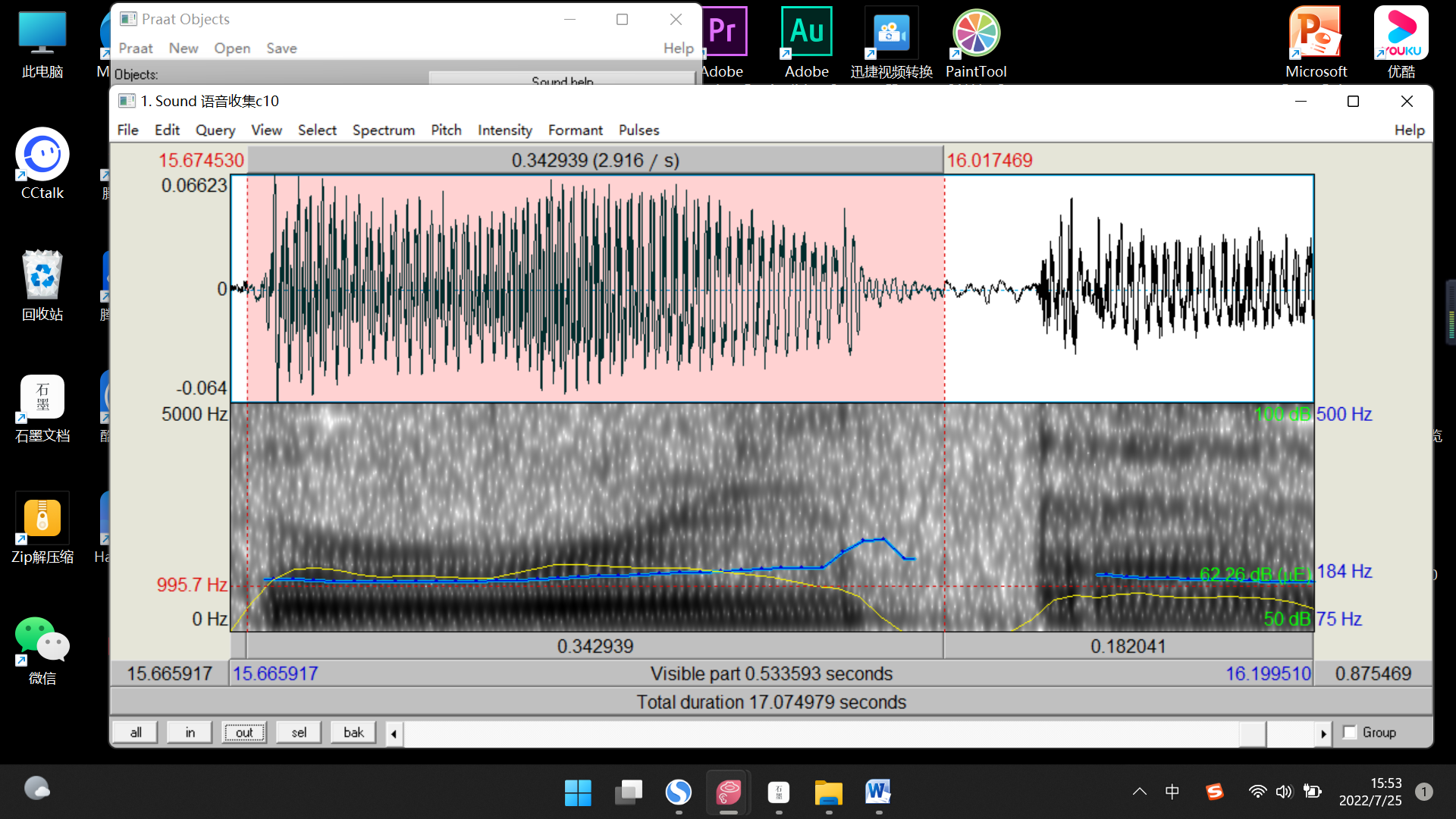

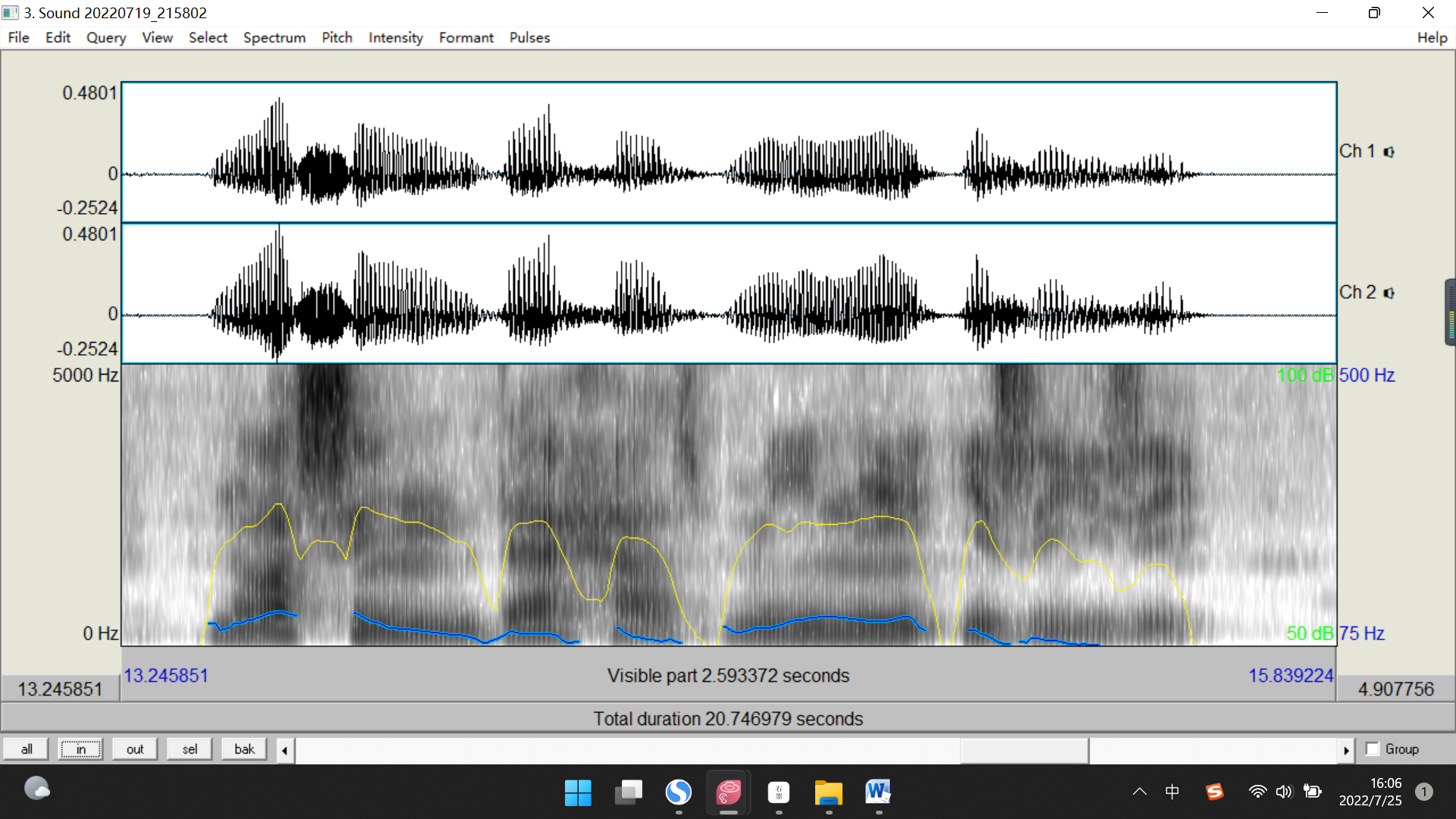

They are prone to use indicative moods when communicating with others; the tone is lower than in other accents in China. In Table.1, the column shows that most native Liaoning accent speaker thinks that their mother tongue has an influence on the phonetic change and tone of English pronunciation acquisition. Hence, most of the Chinese EFL learners in Liaoning province always read a Yes-no question sentence as declarative sentences. From Figure 1, we can see the slope of the pitch diagram is inclined to 0, which means the pitch is stable, and so is the tone of speaking. Besides, according to the voice messages, it can be identified that the people in Liaoning are more likely to add stress at the end of a sentence to strengthen their attitude, just as shown in Figure.3, at which showed the pitch diagram while the interviewees reading a long sentence and the decreasing in each end of the blue lines show the tone of their speaking, which means their tone are prone to be katabatic in the end. Hence, the Liaoning learners usually perform worse in plosive such as /t/, /k/, /p/ and so on, especially when the plosive is located at the end of a phrase or sentence. The word ‘world’ can be the best, and most typical example of the Chinese Liaoning accent English because instead of ignoring the pronunciation of /əl/, they would pronounce /d/ very clearly. For example, when the native speakers pronounce ‘good,’ the /d/ would be plosive, but for the Liaoning accent learners, they always pronounce it as ‘gu’ and ‘də’ separately, in which the /d/ sound was pronounced very clearly. What’s more, this feature would also cause some syllable problems. The data in the questionnaire shows that there is 64.29% of all think they are bad at the usage of connected speech skills.

Table 1 – influential factors

The factors that influence the oral language most by the Liaoning dialect | total | proportion |

phonetic change | 70 |

|

tone | 86 |

|

stress | 50 |

|

stop consonant | 31 |

|

syllable | 22 |

|

rhythm | 35 |

|

Figure 1 slope of pitch diagram

Figure 3 recording's pitch diagram

Furthermore, in Liaoning English class, students have no correct teaching in pronunciation while learning a second language. According to Table 2, there are 75.4% among 126 persons whose English teachers let student follow their pronunciation as the primary method in the class. There are, nevertheless, 44.45% person who think their teacher has less or more accent in speaking English. That may be the main reason why so many people in Liaoning province cannot distinguish the negative transfer from L1 to their L2 pronunciation while learning English.

Table 2 – the method used in teaching

The method teachers used in teaching pronunciation | total | proportion |

Read after the teachers’ pronunciation | 95 |

|

Read after the recording tape | 31 |

|

Because of some historical reasons, the Liaoning accent can be regarded as a mixture of the Beijing accent, the Shandong accent, and the local Manchu dialect. It can be deemed as one of the regional accents that sounds mostly approach to mandarin. Hence, when we determine the feature of this accent, we don’t need to concern too much about how they use their tongue, especially when they pronounce /n/ and /l/. For the EFL learners themselves, People who use Liaoning accent as their first language probably do worse in plosive and syllable, so this condition may add some difficulties when reading the whole sentence fluently and eventually lead to the problem of connected speech as the proportion showed in Table.3 that nearly 65% of the 126 participants don’t know how to do connected speech naturally. In the recording of the interview, most interviewee has a verbatim pronunciation. The American accent may be more accessible for the Chinese EFL learners to imitate because they are used to being rhotic when pronounce, and such an accent always pronounce /ə/ clearly in each word. To tackle this problem, the EFL learners are supposed to have an accurate and correct distinction on the way to reading phonetic symbols and practice opening their mouths and reading slides from one vowel to the other when they read diphthongs.

Table 3 – self-evaluated on connected speech

Can you read connected speech correctly? | total | proportion |

No | 29 |

|

Seldom | 36 |

|

Not sure | 16 |

|

Sometimes | 36 |

|

Adapt at connected speech | 9 |

|

Since English is one of the subjects of the College Entrance Examination, Chinese EFL learners start learning English at a very young age. In another word, the pronunciation of English teachers may have dominant influence on the EFL learners in Liaoning province because they are prone to teach the pronunciation by asking students to speak follow the teachers’ example. So in the initial stage, the English teacher would be the most influential in acquiring a native accent. Because there is no specific dialect, which has a totally independent word and pronunciation system, but just a different accent, you can hear that almost each learner studies in this kind of condition. It would be a little wired and distant for them to try to speak in the proper English accent or even Chinese.

4. Conclusion

On the one hand, the negative transfer from L1, in the individual aspect, plays a pivotal role in the process of SLA. Based on the above information, it is evident that identify that the Chinese EFL learners in Liaoning province can be influenced by the negative language transfer in the aspect of segmental and more of some suprasegmental details such as rhythm, stress, rhotic pronunciation, and lack of sliding awareness in reading diphthongs. Because there is no consonant like /θ/ or /ð/ in Chinese pinyin, the Chinese EFL learners always use /s/ or /d/ to replace the consonant. As for the Liaoning learners, they always ignore the /l/ appearing at the end of a word. Lacking the awareness of their accent and having no active conscience in correcting the English pronunciation, the incorrect English pronunciation has rooted in their memory, mainly being influenced by the negative transfer from their mother tongue.

On the other hand, there still exist some external factors which cannot be noticed in the process of SLA. The initial English teacher in one’s life can guide the way to study spoken English, as well as the environment, friends, and family members surrounding the learners. In that case, it acquires high sensitivity to English pronouncing tone to examine one’s speech recording. Thus, the EFL learners ought to create an English-speaking environment and try to get used to the tone of English. More attention, to the Chinese English education system, should be paid to English speaking and listening skills for Chinese learners.

Besides the above findings, there are still some limitations in this study. Though 126 participants were recruited for the questionnaire, the sample size of the study remains not so sufficient for giving a generic and decisive verdict in identifying how the Chinese accent influence English tone acquisition. It is limited that only the Liaoning accent was considered because there are so many kinds of dialects or accents in China. Future studies are suggested to give an overview of each region or province accent in China.

References

[1]. Karim K, Hossein N. (2013). First Language Transfer in Second Language Writing: An Examination of Current Research. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 1(1), (Jan., 2013) 117- 134

[2]. Alonso, M. R. (1997). Language transfer: Interlingual errors in Spanish students of English as a foreign language. Revista alicantina de estudios ingleses, No. 10 (Nov. 1997); pp. 7-14.

[3]. Commissaire, E., Duncan, L. G., & Casalis, S. (2011). Cross‐language transfer of orthographic processing skills: A study of French children who learn English at school. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(1), 59-76.

[4]. Zhang, H. (2013). The second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese tones by English, Japanese and Korean speakers (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

[5]. Chan, A. Y., & Li, D. C. (2000). English and Cantonese phonology in contrast: Explaining Cantonese ESL learners' English pronunciation problems. Language Culture and Curriculum, 13(1), 67-85.

[6]. Wu, K. (2019). WING-WING OR WIN-WIN: A CASE STUDY OF THE INFLUENCES OF CHINESE SOUTHWESTERN DIALECTS IN ENGLISH PRONUNCIATION.

[7]. Yeung, S. S., & Ganotice, F. A. (2014). The role of phonological awareness in biliteracy acquisition among Hong Kong Chinese kindergarteners who learn English-as-a-second language (ESL). The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 333-343.

[8]. Gilakjani, A. P. & Ahmadi, M. R. (2011) Canadian Center of Science and Education. 1120 Finch Avenue West Suite 701-309, Toronto, OH M3J 3H7, Canada. Tel: 416-642-2606; Fax: 416-642-2608; e-mail: elt@ccsenet.org; Web site: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt

[9]. Bian, F. (2013). The Influence of Chinese Stress on English Pronunciation Teaching and Learning. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 199-211.

[10]. Tahta S, Wood M, Loewenthal K. Foreign Accents: Factors Relating to Transfer of Accent from the First Language to a Second Language. Language and Speech. 1981;24(3):265-272. doi:10.1177/002383098102400306

[11]. Zhang, H. (2007). A phonological study of second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese tones (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

[12]. Zhang, L. (2021). Common Problems in English Pronunciation Among Chinese Learners and Teaching Implications. Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 5(5), 33-38.

Cite this article

Huang,X. (2023). The Influence of Chinese Dialect on English Pronunciation Acquisition: Evidence from Liaoning Accent as An Example. Communications in Humanities Research,3,241-247.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 1

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Karim K, Hossein N. (2013). First Language Transfer in Second Language Writing: An Examination of Current Research. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 1(1), (Jan., 2013) 117- 134

[2]. Alonso, M. R. (1997). Language transfer: Interlingual errors in Spanish students of English as a foreign language. Revista alicantina de estudios ingleses, No. 10 (Nov. 1997); pp. 7-14.

[3]. Commissaire, E., Duncan, L. G., & Casalis, S. (2011). Cross‐language transfer of orthographic processing skills: A study of French children who learn English at school. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(1), 59-76.

[4]. Zhang, H. (2013). The second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese tones by English, Japanese and Korean speakers (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

[5]. Chan, A. Y., & Li, D. C. (2000). English and Cantonese phonology in contrast: Explaining Cantonese ESL learners' English pronunciation problems. Language Culture and Curriculum, 13(1), 67-85.

[6]. Wu, K. (2019). WING-WING OR WIN-WIN: A CASE STUDY OF THE INFLUENCES OF CHINESE SOUTHWESTERN DIALECTS IN ENGLISH PRONUNCIATION.

[7]. Yeung, S. S., & Ganotice, F. A. (2014). The role of phonological awareness in biliteracy acquisition among Hong Kong Chinese kindergarteners who learn English-as-a-second language (ESL). The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 333-343.

[8]. Gilakjani, A. P. & Ahmadi, M. R. (2011) Canadian Center of Science and Education. 1120 Finch Avenue West Suite 701-309, Toronto, OH M3J 3H7, Canada. Tel: 416-642-2606; Fax: 416-642-2608; e-mail: elt@ccsenet.org; Web site: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt

[9]. Bian, F. (2013). The Influence of Chinese Stress on English Pronunciation Teaching and Learning. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 199-211.

[10]. Tahta S, Wood M, Loewenthal K. Foreign Accents: Factors Relating to Transfer of Accent from the First Language to a Second Language. Language and Speech. 1981;24(3):265-272. doi:10.1177/002383098102400306

[11]. Zhang, H. (2007). A phonological study of second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese tones (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

[12]. Zhang, L. (2021). Common Problems in English Pronunciation Among Chinese Learners and Teaching Implications. Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 5(5), 33-38.

55.56%

55.56%

68.25%

68.25%

39.68%

39.68%

24.6%

24.6%

17.46%

17.46%

27.78%

27.78%

75.4%

75.4%

24.6%

24.6%

23.02%

23.02%

28.57%

28.57%

12.7%

12.7%

28.57%

28.57%

7.14%

7.14%