1.Introduction

Traditional media outlets like movies, television, and print publications have been investigated throughout the years for their potential to exacerbate anxiety and depression symptoms related to body image issues [1]. It is said that viewing these photographs encourages valuing these idealized and unrealistic body shapes. A person's ideas, feelings, and perceptions regarding their body are referred to as their body image [2].

Researchers are currently investigating the correlation between online social media use and perceptions of body image. Studies have shown the link between using social media frequently and having negative body image issues. For instance, using Instagram frequently is linked to body dissatisfaction [3]. According to [4], these issues constitute a public health problem that may have harmful psychological and physiological consequences, such as eating disorders and low self-esteem.

A pivotal attribute distinguishing social media from traditional media lies in self-disclosure content. Individuals actively decide how to engage with social media instead of passive consumption in traditional media. For instance, users can engage in various activities on social media, such as sharing photos and videos, 'liking,' and commenting on others' posts.

Through social media, people have a forum to share their opinions as commentators and receive feedback from content creators, in addition to embracing body image norms that encourage social comparison. The significance of the impact of comments and feedback on social media on the way information is received and processed has been explored in previous articles, sometimes even exceeding the content of the conversation itself [5,6].In other words, comments made by other users might contextualize posts and affect how viewers perceive their bodies. In other words, viewers' perceptions of the body portrayed in a body image post as an ideal in line with favorable or negative comments can influence how satisfied they are with their bodies [7].

The presentation of body ideals for women on social media is thought to be intensified by these different types of interactions because women are more likely to perceive these ideals as normal, expected, and essential to attractiveness [8]. The rigid standards of physical attractiveness that women are subjected to appear to have an impact on how women perceive and manage their bodies and weight [9,10], making women more likely than men to be victims of body shaming [9,11,12]. In addition, women are more likely to be biased than men because of their weight, adding to pre-existing disparities.

Women and girls invest significant time and effort in capturing and curating images for online display, which involves capturing multiple shots for selection, utilizing favorable lighting to accentuate desired features, and adopting poses that convey a slender appearance [13]. The emotional state of women can be significantly influenced by the positive feedback received from others. While sharing aesthetically pleasing photos may seem harmless at first, the impact can shift based on the responses they evoke [14]. An experimental study has revealed that posting photos that welcome affirmative comments leads to heightened self-objectification and an intensified focus on body image for women [15]. Due to body expectations and self-objectification, an increasingly common phenomenon is that female consumers are paying more attention to online reviews when browsing social media platforms, whether from strangers or acquaintances [16]. Specifically, an increase in user self-objectification means they care more about their body image. Although many studies indicate that the comments of others negatively affect female users' body image, it has been shown that positive, appearance-related complementary comments in female users also lead to self-objectification than negative comments [17]. Self-objectification amplifies the user's awareness of body perspective [18].

The primary focus of studies on the effects of feedback on social media has been on examining the relationship between positive and negative comments and their effects on body image issues [19,20,15]. This conclusion could be reached by reviewing earlier research.

People can be negatively affected by critical comments from peers about their bodies, leading to concerns about body image, such as eating disorders, according to a previous study [21]. Moreover, people's attitudes toward their bodies are influenced by various groups of people, including peers, family, media users, and themselves, as noted in previous study [22]. These generalizations inspired the main focus of this research.

A hypothesis has emerged that the relationship between the poster and the person giving feedback (i.e. likes/comments) may have different impacts on the perception of body image by the comments. Our research attempts to reveal the different effects of feedback from close acquaintances and unknown individuals on body image. It is worth noting that so far, the academic community has paid little attention to familiarity in the field of social media.

The research also intends to investigate the editing habits of people before posting their content online to find correlations with potential body image dissatisfaction. Additionally, behaviors related to social comparisons are analyzed in the study of whether browsing celebrities or friends’ posts would cause a difference in their body image satisfaction.

Though most of the prior studies used women as their main objectives, the gender difference of participants in those studies could be another variable. Studies showed that body image dissatisfaction exhibits a higher prevalence among women compared to men. Compared to women, men were more likely to be satisfied with their body image, appearance, and weight [23]; however, there is a potential shift in which men are experiencing an increasingly adverse impact while women's experiences might be lessening [24].

2.Method

To investigate the research questions, a questionnaire was conducted to collect quantitative data.

2.1.Participants

The survey was advertised on Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn). The survey collected 229 respondents ranging in age from 15 to 60 from China. The sample comprised 49 participants aged between 15 and 18 (21.4 %), 98 aged between 19 and 22 (42.79 %), 33 aged between 23 and 27 (14.41 %), 41 aged between 28 and 35 (17.9 %), 4 aged between 36 and 45 (1.75 %), and 3 aged between 46 and 60 (1.31 %). The exception is the only participant who is aged below 14 (0.44 %), and this particular response was excluded from the research. The cause for the exclusion is that participants below the age of 14 are considered immature to have comprehensive perceptions of body image. Self-identification was used to identify gender for this investigation. Non-binary, questioning, or other gender identification (n=4) individuals were excluded from this research due to the low sample size for analysis.

The sample included 165 cisgender women (72.05%), 60 cisgender men (26.2%), 3 non-binary (1.31%), and 1 other gender identity (0.44%). This study collected respondents on various levels of education: 6 had not graduated from high school (2.62%); 54 had a high school, college, or associate's degree (23.58%); 134 had a bachelor's degree (58.52%); and the remaining 35 had a master's or doctoral degree (15.28%).

2.2.Procedure

WeChat, a Chinese social media site, was used to find participants. Participants were not disqualified based on their gender identity or degree of education. The survey was referred to be an online investigation into social media use. Participants responded to the online questions in their usual settings (such as their homes or libraries).

2.3.Measures

2.3.1.Social media usage habits

Five questions were applied to construct the overall pattern of participants’ social media use, including two inquiring about details of their browsing convention and three targeting their posting style.

1)The two browsing conventions: screen time usage on body-image-related content (e.g.: cosmetics, fitness), and participants’ attitudes towards those contents were separately asked.

2)The three posting-style questions refer to whether participants normally edit their images before posting them on social media; the frequency of posting images on social media; and the frequency of them editing those posts.

2.3.2.Appearance-related social media consciousness (ASMC)

An appearance-related social media consciousness scale(ASMC) was used to assess how individuals view their body image under the background of social media [25]. Using a seven-point response scale (1 = never, 7 = always), participants rated the degree to which 13 statements relevant to body images and specific behavior in social media (e.g. “I try to guess how people on social media will react to my physical appearance in my pictures. ”).

2.3.3.Comments preference

Since the influence of close peers and unknown individuals is categorized and identified as the main focus of the study, two corresponding questions were integrated:

1)The most viewed types of images (e.g.: celebrities or close peers)

2)Participants’ preferences towards reactions from either unknown individuals or close peers (“Which of the following scenes would make you feel the best when you images of yourself on social media?” A. receiving likes from friends on WeChat; B. friends leaving comments like 'you look amazing!' on WeChat; C. Online friends commenting "I want to know where you got this skirt!" on TikTok; D. receiving likes by online friends on Xiaohongshu; E. none of the above).

2.4.Data Analysis

For findings 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5, this analysis has reclassified the options in favor of clarity. In 3.4, people who chose "Receive likes from friends" and "Friends left comments like 'you look amazing!'" are classified as "people who value their friends' comments more" because the subject of these two options is "friends" in terms of expression. The respondents for findings 3.3 and 3.4 were also reclassified for the same concern.

The ASMC ratings were calculated to make comparisons on questions, and the results of this were obtained by calculating the average of each person's total score.

3.Findings and Discussion

3.1.Habits of editing photos

Table 1: mean (ASMC) ratings of different posting habits

Filter |

Do not filter |

|

N |

154 |

75 |

Average ASMC score |

4.45 |

3.23 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always)

Analysis in Table 1 examined the usage habits of the respondents from the survey. The average of the group of people who have the habit of editing photos was 4.45 and the average of the group of people who don’t have the habit of editing photos was 3.23, which indicates that people who have the habit of editing photos before they post feel more dissatisfied with their bodies than people that don’t have the habit of editing photos.

3.2.Frequency of posting photos

Table 2: Mean (ASMC) ratings of different posting frequencies.

Never |

Once a year |

1-5/half a year |

1-6/month |

1-7/week |

Everyday |

|

Average ASMC score |

3.39 |

3.04 |

4.1 |

4.34 |

4.44 |

3.79 |

Number of results |

14 |

31 |

77 |

75 |

24 |

7 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always. )

For this analysis, we set 6 options for respondents to report how often they posted photos on social media platforms, the 6 options are: never, once a year(or even less), one to five times in six months, one to six times a month, one to seven times a week and almost every day which can be divided as 3 groups: Low, mid and high frequencies.

It can easily be seen in Table 2 that the average of the third, fourth, and fifth groups was bigger than the other three groups, among them, the average of the fifth group(4.44) was the biggest. Therefore, people who post their photos in the mid frequencies are more unsatisfied with their bodies than people who post photos in the low or high frequencies.

3.3.Screen Time Usage on Body-image-related Contents

Table 3: Mean (ASMC) Ratings of Screen Time Usage on Body-image-related Contents

<1h |

1-3h |

3-5h |

>5h |

|

N |

137 |

57 |

25 |

10 |

Average ASMC Score |

3.75 |

4.27 |

4.84 |

5.04 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always)

As seen in Table 3, when the approximate screen time use increases, the average ASMC-scale score of participants increases, meaning the longer they spend on social media viewing body-image-related content, the more concerned they are about their self-presentation on social media. To be more specific, people who browse beauty content for more than 5 hours have the highest ASMC score at 5.04, compared to only 3.75 in respondents of less than 1h group.

3.4.Attitudes Toward social media

Table 4: Mean (ASMC) ratings of Participant Attitudes Toward Body-image-related Contents

Positive |

Neutral |

Negative |

|

N |

116 |

92 |

21 |

Average ASMC score |

4.10 |

3.59 |

4.42 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always)

Adding to the investigation from section 3.3, participant attitudes toward such content were also examined by the question “What are your attitudes towards fitness, dressing, and beauty content on social media”.

As seen in Table 4, selections were incorporated into three: the negative group, the neutral group, and the positive group. According to the results, participants who held neutral viewpoints had the lowest level of body dissatisfaction(3.59), indicating that apathy towards body-image-related content corresponds to a comparatively high degree of unconcern about body satisfaction. In contrast, participants claiming to be self-inspired which is considered as having a positive attitude by such content are having higher tendencies of developing body dissatisfaction(ASMC=4.10). Among all attitudes, the group with negative attitudes gained the highest score.

3.5.Browsing celebrities or friends

Table 5: Mean (ASMC) Ratings of Browsing Celebrities Or Friends

Browse photos of close peers |

Browse photos of influencers/idols |

|

N |

108 |

106 |

Average ASMC score |

3.89 |

4.31 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always)

As seen in Table 5, participants reported browsing photos of celebrities more revealing a higher average score on the ASMC scale at 4.31. Even though the statistics seemed similar, participants browsing photos of close peers performed better on the ASMC scale at 3.89. In addition, nine participants wrote in the option “others” but none of them fitted with the study, so these 9 samples were excluded.

3.6.Seeking approval: Comments from close peers vs. unknown individuals

Table 6: Mean (ASMC) Ratings of Seeking Approval

Comments from close peers |

Comments from unknown individuals |

|

N |

187 |

27 |

Average ASMC score |

4.09 |

4.48 |

(Note: ASMC ratings ranged from 1 = never to 7 = always)

As demonstrated in Table 5, people who care more about comments from unknown individuals to their photos feel more unsatisfied than people who care more about comments from close peers to their photos(ASMC=4.48). Excessive variation in numbers between people who care about comments from close colleagues and comments from unfamiliar people may affect the accuracy of the conclusions. Most people may care more about comments from close peers instead of comments from unknown individuals.

12 participants wrote in the option “others” but only one answer was valid for the study. The answer “Being asked for clothing links on any social media” can be considered as caring more about comments from unknown individuals so we put it into this group.

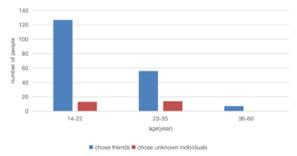

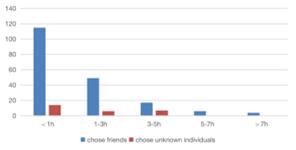

Figure 1: Age distribution of preferred comments from friends and unknown individuals

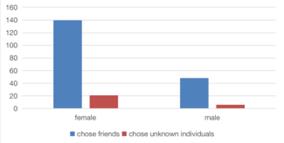

Figure 2: Gender distribution of preferred comments from friends and unknown individuals

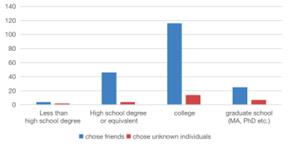

Figure 3: Educational level distribution of preferred comments from friends and unknown individuals

Figure 4: Screen time distribution of preferred comments from friends and unknown individuals

Analysis for demographic factors was also conducted to identify other differences in characteristics between these two groups. As shown in Graph 2, Graph 3, and Graph 4, people with both preferences showed the same trend in gender identity, screen time, and educational level. To be more specific, female respondents and college-level education accounted for the biggest, and most of the participants with two preferences used screens to browse social media content for less than one hour.

However, slight differences appeared in age distribution in the two preference groups. Specifically, people who enjoyed receiving comments from close peers were concentrated between the ages of 14 and 22. However, people who valued feedback from unknown individuals were concentrated at the age of 23-35.

3.7.Gender differences

3.7.1.Similarities

Table 7: Screen time use of different genders

<1h |

1-3h |

3-5h |

>5h |

|

female |

88 |

46 |

22 |

8 |

male |

46 |

9 |

3 |

2 |

Our result is that the option with the highest number of choices among both genders is that respondents watched less than one hour each day about fitness, dressing, and beauty content on social media.

3.7.2.Differences

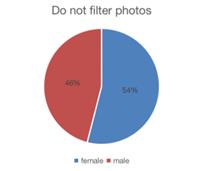

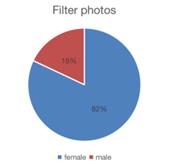

Figure 5: Filtering habits of different genders

As shown in Graph 5, it is found that the female group demonstrated a higher percentage of editing photos compared to the male group(54%). In addition, among the female group, the number of females with editing photos habits(82%) far exceeds the number of females that don’t have editing photos habits(18%); While among the male group, the number of males with editing photos habits is nearly equal to the number of males without editing photos habits.

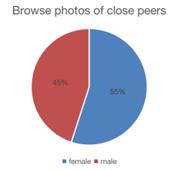

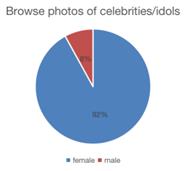

Figure 6: Browsing preferences of different genders

According to Graph 6, when viewing photos on social media, males are more likely to watch photos of friends, classmates, or workmates(45%) instead of watching photos of celebrities, idols, or bloggers(8%). However, females love to watch photos of celebrities, idols, or bloggers more(92%).

Table 8: Attitudes toward body image-related content of different genders

Positive |

Neutral |

Negative |

|

female |

94 |

58 |

12 |

male |

21 |

32 |

7 |

In Table 8, outcomes revealed that most of the males(32) have neutral attitudes toward beauty-related content, contrasting with the attitudes of females, in which most of them feel positive about the content on social media(94).

4.Discussion

Consistent with a previous study conducted on Instagram, people who have more time spent on social media have higher levels of body dissatisfaction [26]. Therefore, this study extends previous research, demonstrating that this conclusion can be applied to the background of Chinese social media platforms such as Weibo, TikTok, and Xiaohongshu.

Since self-comparison is a common phenomenon when users browse social media, some surveys were conducted to assess facts relating to self-objectification and appearance comparisons [14], our main research question tries to examine whether people’s preferences in receiving feedback from unknown individuals or close peers will influence their body images concerns. The significance of the study in this regard is to answer the uncertainty on attitudes toward social media adoption for body image, whether positive, neutral, or negative. However, the survey conducted for this paper found that a vast majority (187) of respondents said they were more interested in receiving feedback from close peers than respondents valuing comments from unknown individuals (27) so it might not be reliable to compare their ASMC rating directly. However, this survey finds that slight differences appeared in age distribution in the two preference groups. These two problems might be settled in future studies, trying to collect a larger quantity of data and figure out if there is a correlation between age, preferences of receiving comments from different connection strength people, and how they perceive their body image.

Previous studies have examined negative comparisons about one’s appearance on social media such as Facebook, finding a strong correlation between comments from different connection strength groups and body image perception [27]. To expand this previous study, we tested the link between body image perception and photo browsing habits. We found the same trend as previous studies, where people who browse more celebrity photos regularly tend to be more negative about body image concerns. It is also advisable that influencers and idols should post less idealized photos on social media.

Results also indicate that people having photo-editing habits in this survey have higher levels of body dissatisfaction, which corresponds with previous research [28].

This study observed that the ASMC scores of women were higher than men after using social media, expanding the statement relating to body image perception in different genders of other scholars [29]. However, former studies found more similarities than differences across genders on social media [14], which is slightly different from this survey. This research found that males have a more neutral attitude toward body image-related content, while females have a more positive attitude toward this type of content. There is also a surprising finding- the number of men and women who do not have the habit of editing pictures is almost the same. This difference may result from the diverse attitudes toward body image content from Chinese and Westerners, or the attributes between Chinese appearance-related social media and Western appearance-related social media. But we failed to explore the cause of this difference so these factors might indicate that scholars could conduct more research on mental diversities between males and females when discussing the influence of social media.

5.Limitations

Despite the results, the study still contained several limitations. Since the major research focus of this study is on whether the identity of the commenter influences individuals’ body-image perception on social media and given that this topic is rarely discussed in previous literature, questions within the questionnaire for assessing factors relating to this focus were all designed by the research group. Only a few sets of questions (around 2-3 for each section, three sections in total) were used to measure abstract variables, for instance, one’s perception of body image and their fondness for others. The questions themselves are insufficient in number, leaving the validity and reliability of the questionnaire debatable.

Data was collected in the form of questionnaires, denoting that the study only indicates certain traits and is unable to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The association between variables can result from both directions. For instance, it could be individuals who edit their photos on social media are more dissatisfied with their bodies, or it could be individuals who have body dissatisfaction editing their photos on social media.

Regardless of the scale questions quoted from a substantiated test, the AMSC scale, authentic and credible Chinese translations were inaccessible. Leaving no other solution but doing the translation by the research group. Back translation was applied during the process to enhance the accuracy and minimize the effect of cross-language translation. However, lexical borrowing terms like “feel bad about oneself” do not have direct Chinese translations as the expression does not exist in either the Chinese semantic field or the conventional Chinese oral context. Ambiguous translation could create misleadingness and further affect the reliability of the results.

In addition, participant bias was also an unavoidable limitation during data collection. Considering that most questions within the questionnaire had a clear connection with body image and social media, and considering the potential observer-expectancy effect, it is likely that demand characteristics may occur among the participants. Observer-expectancy effect describes the tendency where the expectations or beliefs of the experimenters unintentionally influence the behavior of participants. And as the participants may interpret the purpose of the study, it could subconsciously impact their replies.

Because the distribution platform, WeChat, possesses interpersonal communication [30], its distinctive characteristics may cause a possible sampling bias. Most participants are contacts of the researchers, forming a condensed population and hence, lacking generalizability. Besides, even though the number of male participants is sufficient to support evaluations and analysis, the small population hinders the generalizability of the results for males. Thus, additional studies should be conducted.

6.Future Directions

The majority of experimental research has concentrated on samples of young, white women who reside in Western nations [14] and on appearance-focused social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and Snapchat which are popular in Western nations.

WeChat is deemed as a utility for getting social support since, according to the most recent data from Tencent in June 2022, it has more than one billion 200 million daily active users worldwide and has a spectacular year-on-year growth of 3.8%. As a result, we gathered a sizable number of samples, of which one-third were male samples. This indicates that future surveys may attempt to use WeChat to assess male body image concerns.

7.Conclusion

By using the ASMC scale, we observed several interesting connections between body image and seeking approval which is the comments from close peers versus unknown individuals. People who browse more photos of idols or celebrities and people who care more about comments from unknown individuals on their photos may have a higher level of body dissatisfaction. Also, we found several remarkable gender differences: males love to watch photos of friends, workmates, or classmates more on social media, but females love to watch photos of celebrities, idols, or bloggers more. We examined that people may value comments from close peers more than comments from unknown individuals when posting photos on social media. Slight differences have also been found in age distribution in the two preference groups. People who enjoyed receiving comments from close peers were concentrated at the age of 14-22, however, people who valued feedback from unknown individuals were concentrated at the age of 23-35.

Acknowledgment

Haolan Xu, Yixuan Han, Siyuan Zhou, Yiran Li and Yifei Tang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H.(2009). Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 683–698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

[2]. Grogan, S. (2008). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children (second ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

[3]. Sherlock, M., & Wagstaff, D. L. (2019). Exploring the relationship between frequency of Instagram use, exposure to idealized images, and psychological well-being in women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 482–490.

[4]. Bucchianeri, M. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2014). Body dissatisfaction: An overlooked public health concern. Journal of Public Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-11-2013-0071

[5]. Waddell TF and Sundar SS (2017) # thisshowsucks! The overpowering influence of negative social media comments on television viewers. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 61: 393–409.

[6]. Walther JB, DeAndrea D, Kim J, et al. (2010) The influence of online comments on perceptions of antimarijuana public service announcements on YouTube. Human Communication Research 36: 469–492.

[7]. Kim, H. M. (2020). What do others’ reactions to body posting on Instagram tell us? The effects of social media comments on viewers’ body image perception. New Media & Society, 146144482095636. doi:10.1177/1461444820956368

[8]. Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

[9]. Brownell, K. D. (1991). Dieting and the search for the perfect body: Where physiology and culture collide. Behavior Therapy, 22, 1–12.

[10]. Grogan, S. and Richards, H. (2002) Body image: Focus groups with boys and men. Men and Masculinities, 4(3), 219-232.

[11]. Murray, S. H., Touyz, S. W., & Beumont, P. J. V. (1995). The in-fluence of personal relationships on women’s eating behaviorand body satisfaction. Eating Disorders, 3, 243–252.

[12]. Wadden T. A., & Stunkard, A. J. (1985). Social and psychologi-cal consequences of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine, 103, 1062–1067.

[13]. Tiggemann, M., & Velissaris, V. G. (2020). The effect of viewing challenging “reality check” Instagram comments on women’s body image. Body Image, 33, 257–263.

[14]. Vandenbosch, L., Fardouly, J., & Tiggemann, M. (2022). Social media and body image: Recent trends and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 45, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002

[15]. Vendemia, M. A., & DeAndrea, D. C. (2021). The effects of engaging in digital photo modifications and receiving favorable comments on women’s selfies shared on social media. Body Image, 37, 74–83.

[16]. Choukas-Bradley, S., Nesi, J., Widman, L., & Higgins, M. K. (2019). Camera-ready: Young women’s appearance-related social media consciousness. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000196

[17]. Slater, A. , & Tiggemann, M. (2015). Media Exposure, Extracurricular Activities, and Appearance-Related Comments as Predictors of Female Adolescents’ Self-Objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(3), 375-389–389.

[18]. Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

[19]. Calogero, R. M., Herbozo, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Complimentary weightism: The potential costs of appearance-related commentary for women’s self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 120–132. http://dx.doi. org/10.1111/j.1476402.2008.01479.x

[20]. Tiggemann, M., & Boundy, M. (2008). Effect of environment and appearance compliment on college women’s self-objectification, mood, body shame, and cognitive performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 399–405. http://dx. doi.org/10.1111/j.14716402.2008.00453.x

[21]. Varnagirytė, E., & Perminas, A. (2022). The impact of appearance comments by parents, peers and romantic partners on eating behaviour in a sample of young women. Health Psychology Report, 10(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2021.111294

[22]. Van den Berg, P., Thompson, J. K., Obremski-Brandon, K., & Coovert, M. (2002). The Tripartite Influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(5), 1007-1020. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00499-3.

[23]. Voges, M. M., Giabbiconi, C.-M., Schöne, B., Waldorf, M., Hartmann, A. S., & Vocks, S. (2019). Gender Differences in Body Evaluation: Do Men Show More Self-Serving Double Standards Than Women? https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00544

[24]. Brennan, M.A., Lalonde, C.E., & Bain, J. (2010). Body Image Perceptions: Do Gender Differences Exist? Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 15, 130-138.

[25]. Maheux, A. J., Roberts, S. R., Nesi, J., Widman, L., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2022). Psychometric properties and factor structure of the appearance-related social media consciousness scale among emerging adults. Body Image, 43, 63–74.

[26]. Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. R. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media and Society, 20(4), 1380-1395–1395.

[27]. Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82–88.

[28]. Wang, Y., Xie, X., Fardouly, J., Vartanian, L. R., & Lei, L. (2021). The longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between selfie-related behaviors and self-objectification and appearance concerns among adolescents. New Media and Society, 23(1), 56-77–77.

[29]. Franchina, V., & Coco, G. L. (2018). The influence of social media use on body image concerns. International Journal of Psychoanalysis & Education 10 (1), 6-14.

[30]. Wang, G., Zhang, W., & Zeng, R. (2019). WeChat use intensity and social support: The moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 244–251.

Cite this article

Xu,H.;Han,Y.;Zhou,S.;Li,Y.;Tang,Y. (2024). Seeking Approval of Appearance — The Link Between Social Media Use in China and Body Image Concerns. Communications in Humanities Research,29,1-12.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H.(2009). Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 683–698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

[2]. Grogan, S. (2008). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children (second ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

[3]. Sherlock, M., & Wagstaff, D. L. (2019). Exploring the relationship between frequency of Instagram use, exposure to idealized images, and psychological well-being in women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 482–490.

[4]. Bucchianeri, M. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2014). Body dissatisfaction: An overlooked public health concern. Journal of Public Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-11-2013-0071

[5]. Waddell TF and Sundar SS (2017) # thisshowsucks! The overpowering influence of negative social media comments on television viewers. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 61: 393–409.

[6]. Walther JB, DeAndrea D, Kim J, et al. (2010) The influence of online comments on perceptions of antimarijuana public service announcements on YouTube. Human Communication Research 36: 469–492.

[7]. Kim, H. M. (2020). What do others’ reactions to body posting on Instagram tell us? The effects of social media comments on viewers’ body image perception. New Media & Society, 146144482095636. doi:10.1177/1461444820956368

[8]. Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

[9]. Brownell, K. D. (1991). Dieting and the search for the perfect body: Where physiology and culture collide. Behavior Therapy, 22, 1–12.

[10]. Grogan, S. and Richards, H. (2002) Body image: Focus groups with boys and men. Men and Masculinities, 4(3), 219-232.

[11]. Murray, S. H., Touyz, S. W., & Beumont, P. J. V. (1995). The in-fluence of personal relationships on women’s eating behaviorand body satisfaction. Eating Disorders, 3, 243–252.

[12]. Wadden T. A., & Stunkard, A. J. (1985). Social and psychologi-cal consequences of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine, 103, 1062–1067.

[13]. Tiggemann, M., & Velissaris, V. G. (2020). The effect of viewing challenging “reality check” Instagram comments on women’s body image. Body Image, 33, 257–263.

[14]. Vandenbosch, L., Fardouly, J., & Tiggemann, M. (2022). Social media and body image: Recent trends and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 45, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002

[15]. Vendemia, M. A., & DeAndrea, D. C. (2021). The effects of engaging in digital photo modifications and receiving favorable comments on women’s selfies shared on social media. Body Image, 37, 74–83.

[16]. Choukas-Bradley, S., Nesi, J., Widman, L., & Higgins, M. K. (2019). Camera-ready: Young women’s appearance-related social media consciousness. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000196

[17]. Slater, A. , & Tiggemann, M. (2015). Media Exposure, Extracurricular Activities, and Appearance-Related Comments as Predictors of Female Adolescents’ Self-Objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(3), 375-389–389.

[18]. Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

[19]. Calogero, R. M., Herbozo, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Complimentary weightism: The potential costs of appearance-related commentary for women’s self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 120–132. http://dx.doi. org/10.1111/j.1476402.2008.01479.x

[20]. Tiggemann, M., & Boundy, M. (2008). Effect of environment and appearance compliment on college women’s self-objectification, mood, body shame, and cognitive performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 399–405. http://dx. doi.org/10.1111/j.14716402.2008.00453.x

[21]. Varnagirytė, E., & Perminas, A. (2022). The impact of appearance comments by parents, peers and romantic partners on eating behaviour in a sample of young women. Health Psychology Report, 10(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2021.111294

[22]. Van den Berg, P., Thompson, J. K., Obremski-Brandon, K., & Coovert, M. (2002). The Tripartite Influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(5), 1007-1020. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00499-3.

[23]. Voges, M. M., Giabbiconi, C.-M., Schöne, B., Waldorf, M., Hartmann, A. S., & Vocks, S. (2019). Gender Differences in Body Evaluation: Do Men Show More Self-Serving Double Standards Than Women? https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00544

[24]. Brennan, M.A., Lalonde, C.E., & Bain, J. (2010). Body Image Perceptions: Do Gender Differences Exist? Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 15, 130-138.

[25]. Maheux, A. J., Roberts, S. R., Nesi, J., Widman, L., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2022). Psychometric properties and factor structure of the appearance-related social media consciousness scale among emerging adults. Body Image, 43, 63–74.

[26]. Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. R. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media and Society, 20(4), 1380-1395–1395.

[27]. Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82–88.

[28]. Wang, Y., Xie, X., Fardouly, J., Vartanian, L. R., & Lei, L. (2021). The longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between selfie-related behaviors and self-objectification and appearance concerns among adolescents. New Media and Society, 23(1), 56-77–77.

[29]. Franchina, V., & Coco, G. L. (2018). The influence of social media use on body image concerns. International Journal of Psychoanalysis & Education 10 (1), 6-14.

[30]. Wang, G., Zhang, W., & Zeng, R. (2019). WeChat use intensity and social support: The moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 244–251.