1.Introduction

1.1.Research Background

First used in the 1740s to refer to a group of Puritan Covenanters in southwest Scotland, the term "Whig" was originally pejorative. Still, in its long use, it was forgotten and became the name of a political party, along with the term "Tory". During the Exclusion Act of 1679, the English Parliament was openly divided between those who wanted to disinherit James and those who wanted to retain his inheritance, known as the Whigs and the Tories [1]. The mass base of the Whigs was not the traditional aristocracy but financial and commercial people and Protestants, and after the 19th century, it represented more the interests of the industrial and commercial bourgeoisie. Rather than a political party in the modern sense, the Whigs were more of a political faction, an amalgam of beliefs that followed the principle of "advocating a constitutional monarchy in place of a theocracy, siding with the bourgeoisie and the new aristocracy in favor of Parliament and against the King and the Catholic Church" [2]. It was the forerunner of the modern bourgeois political party, the Liberal Party. It played a significant role in the modern history of Britain.

Although there are different views in historical circles on evaluating the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in Britain, it is undeniable that the Glorious Revolution had a far-reaching influence on the historical development of Britain and even the world. On the one hand, the Glorious Revolution established the long-term stable growth of the British political situation through the mutual compromise between Parliament and the King [3]; on the other hand, the Glorious Revolution also established "Parliamentary Sovereignty," which opened modern Western representative democracy and provided the institutional guarantee for Britain's development into a current state [4]. After the Glorious Revolution, Whig political thought also changed along with the polity, altering the course of British history, and the study of this change is also helpful in our examination of modern political thought. However, there is a lack of comparative understanding of the direct changes in Whig political thought before and after the Glorious Revolution, especially in a specific period.

1.2.Thesis Statement

Through a contrastive analysis of academic documents and Whig’s political thought before and after the Glorious Revolution, this paper aims to illuminate the important influences of the Glorious Revolution on the Whig’s political thoughts, highlight the transformation from four aspects, the role of Parliament, contractual theory, attitudes towards the monarchical power and religious toleration which affect the revolution of modern British political thought.

1.3.Problem Statement

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 is one of the important events in British history, which not only changed the pattern of the British political system but also had a profound impact on the political development of the whole of Europe. In this important revolution, the political ideas of the Whig Party and the Tory Party were constantly improved and enriched, among which the formation and development of the Whig Party's political ideas was an important part of this revolution. Whig political thought played an important role not only in opposing the king's despotism and developing early English liberties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries but also in promoting parliamentary reform in the 19th century and expanding modern democracy. The changes of Whig’s political thoughts are also an important symbol of evolving socio-political transformation. However, there is a lack of comparative studies on the direct changes in Whig political thoughts before and after the Glorious Revolution, especially in a specific period.

This study aims to address this gap by meticulously comparing and analyzing the changes in Whig's political thoughts and their key via the Glorious Revolution and how these changes Shape their political ideology to gain valuable insights into the formation of modern British political ideology.

By using the research method of document analysis, we deeply analyzed the research results of different scholars from home and abroad on the Whig Party and the Glorious Revolution and also studied the relevant speeches and writings of prominent Whig figures. We devote to revealing the key shifts and their characteristics in four aspects: The role of Parliament, contractual theory, attitudes towards the monarchical power, and religious toleration.

The significance of this study lies in its potential to gain a deeper insight into the relationship between historical events and political ideology. By going back to the formation of Whig’s political thoughts from the angle of the Glorious Revolution, we can summarize the law and function between political ideology and real events. Further on, this study could contribute to gaining more insights into how important historical events reshape political thoughts and affect historical progress.

2.Literature Review

2.1.Analysis & Synthesis of the Existing Studies

Herbert Butterfield analyzed and critiqued the Whig approach to interpreting history in his book The Whig Interpretation of History [5]. The book did not address early Whig concepts of political thought but instead inspired later scholars. In The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law, Pocock examined the development of historical thought in seventeenth-century Britain, particularly in relation to the concepts of the Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law. The work reveals the complex interplay between seventeenth-century historical thought, political theory, and practical politics. The book provides insights into the development of British thought during a critical period in its history [6]. In The Origins of the Whigs and Tories, William analyses the etymological origins of the names of the two parties and their use in realpolitik [7]. In Revolution by Degree: James Tyrrell, Julia Rudolph provides an insight into the development of English thought during a critical period in its history. James Tyrrell provides an insight into the development of English thought during a critical period in its history. Qualification: By analyzing the political thought of James Tyrrell before and after the Glorious Revolution, Julia Rudolph illustrates the transformation of Whig thought at that time. To establish the legitimacy of William's rule, the Whigs revisited their historical and theoretical issues through the lens of natural rights and social contract theory [8]. Most of the recent literature on Whig political thought has focused on analyzing the political thought of prominent Whig Party members like Edmund Burke or Locke while giving less consideration to the overall changes in early Whig thought that occurred before and after the Glorious Revolution.

There is a dearth of research in China on the political thought of the Whigs, and a distinct treatise on Whig political thought has not yet been established. Studies and treatises on the same are dispersed across various works. In their co-authored work, 'A Political History of the British Parliament', Professor Shen Han and Professor Liu Xincheng cover Locke's political thought and Whigism after the Glorious Revolution in the relevant chapters. They argue that the historical manifestation of an immature form of Whigism embodies the late maturity of the British bourgeoisie [9]. Professor Yan Zhaoxiang, an expert in British history, has addressed the circumstances surrounding the early Whig Party in several books and essays. In his article, 'The Evolution of the Three Major Political Parties in Britain', he examined the origins of the three modern British political parties and discussed the emergence of the Tories and the Whigs, which are now the Conservative and Liberal parties, respectively [10]. In his book, 'A History of Party Politics in Britain', he closely examined the development and evolution of British political parties, including the content and expression of early Whig ideas. In his second book, 'A History of Political Ideas in Britain', he analyzed the shift from liberal to conservative in early Whig political ideas from the perspective of the development of political ideas in Britain [11,12]. Scholar Ma Hengxiang researched the political thought of the early Whigs from the Exclusion Act of 1679 to 1714, when the Whigs became the dominant party, in his master's thesis [13]. However, unlike this study, he did not analyze the changes in Whig political thought before and after the Glorious Revolution.

2.2.Definition of Whig's Political Thoughts

Political thought also referred to as political trend of thought, political theory or political philosophy.

Some scholars define political thought as a conceptual expression of practical political experience, with its core aim regarding the search for justice required for a good political life [14]. From a Marxist perspective, other scholars argue that political thought is a reflection of the needs, interests, and demands of specific social classes, strata, or groups in a certain era. Political thought serves as a method for designing and implementing programs to seize, establish, and maintain political power. Its core issue is the acquisition and exercise of state power, meaning that the main content of political thought is concerned with how to comprehend, organize, and govern the state. It follows that the primary content of political thought is focused on understanding, organizing, and managing the state. Political thought is conspicuously expressed in multiple forms, including political views, ideas, and doctrines [15]. Liu Zehua broadens the interpretation of political thought by equating it to political conception and divides it into three levels: political psychology, political thought, and political doctrine. Political psychology is characterized by emotions, inclinations, preconceptions, beliefs, customs, habits, and more. It has spontaneity and direct sensibility and is not exclusive to a few ideologues but is possessed by most members in one way or another. Political thought is a type of political consciousness that combines political psychology and political ideology. Political thought is a theorized form of political consciousness that sublimates political psychology and is more systematic. Political doctrine, on the other hand, is a systematic and sometimes philosophical form of political thought [16].

The focus of our research is the political thought of the Whig Party. This paper defines the political ideology of the Whig Party as the political concepts, ideas, and doctrines that have been predominant throughout the ages, based on the research and theme of the project.

2.3.Identification of Gaps in Previous Literature

By analyzing the previous literature and research, we found that there is a lack of comparative understudying on the direct changes of Whig political thoughts before and after the Glorious Revolution, especially in a specific period. It served as the precursor to the modern sense of the bourgeois political party, the Liberal Party. It held a significant position in the modern history of Britain [13], and Previous research on Whig political thought often points out that the Glorious Revolution was a significant turning point for Whig political thought [2].

To some extent, this gap prevents us from exploring the relationship between the Glorious Revolution and the formation of Whig political ideology from a deeper perspective and reflecting on the guiding significance of the historical process of Whig ideological change for the political development of Britain today.

Therefore, we intend to address the gap by meticulously comparing and analyzing the changes in Whigs' political thoughts and their key features by the Glorious Revolution. The second objective of our research is to study how these changes Shape their political ideology to gain valuable insights into the formation of modern British political ideology in this research.

While identifying gaps, we also ensured that our studies were realistic and manageable by delineating specific time periods, which was the scope of our entire study (1679-1760). Meanwhile, to maintain a clear connection and constructiveness between gaps and research objectives throughout our research, we set our research objectives on the basis of this gap.

3.Methodology

In our research, we utilized qualitative research methods to gather relevant information. Denzin and Lincoln argue that qualitative research is a multi-method approach that uses interpretivism and naturalism to explore their subjects, including philosophical perspectives, research paradigms, research approaches, data collection, and data analysis that are completely different from quantitative research [17].

To accurately analyze the changes in Whig political thoughts before and it after the Glorious Revolution.

We employed a qualitative method known as document analysis. Through CNKI and Google Scholar, documents related to Whig political thought and the Glorious Revolution (a total of 24 articles) were collected for combing and analysis. First, a large number of research literature related to the research content is collected and reviewed; secondly, the literature materials are classified and sorted out according to the four keywords of this study. finally, the literature materials are analyzed to extract our own views.

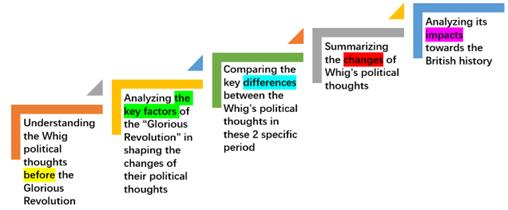

Our objectives of using the document analysis as our research method were to show a feature of coherence and layers of progression, as below (As shown in Figure 1, The research objectives):

1)Understanding the Whig political thoughts before the Glorious Revolution;

2)Analyzing the key factors of the “Glorious Revolution” in shaping the changes in their political thoughts;

Figure 1: THE RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

3)Comparing the key differences between the Whig’s political thoughts in the specific period

4)Summarizing the features of Whig’s political thoughts formation;

5)Analyzing its impacts on British history.

4.Findings

4.1.The Whig's Political Thoughts Before the Glorious Revolution

4.1.1.Overview of Whig Ideology and Principles

The Whigs, also known as the King's Opposition, were primarily formed during the time of parliamentary Exclusion. The term "Whig," referring to Scottish horse thieves and pirates, was initially adopted by the government to refer to the King's Opposition due to its irony and simplicity of writing and gained popularity in the mid-1680s. The Whigs were more intricate and less united than contemporary political parties and shared certain ideology and composition characteristics with the Tories. The Whigs comprised both Presbyterians during the Civil War and the 'rural opposition' of the 1670s. Besides, it included a certain number of radicals, Monmouths, and a handful of political opportunists [13]. However, the Whigs' loss of power over the Exclusion Bill resulted from internal divisions [1]. Yet, the Whigs showed an unparalleled degree of organization and party discipline compared to the previous rural opposition. They had a significant influence in parliament and the countryside, impressive scale, and strength in elections and propaganda. They also had highly influential leaders obedient members and possessed the foundational features of a political party: Both parties presented distinct political platforms by proposing the Exclusion Bill. The contrary stances towards this bill demonstrated each party's political position. The two parties also created durable and secure political entities, establishing a stable core leadership. Additionally, they attempted to affect governmental decisions by wielding power over Parliament. According to today's standards, the Whigs would be more accurately classified as a political party [18]. The party's fundamental principle was to advocate for the substitution of theocracy with constitutional monarchy, aligning with the bourgeoisie and the new aristocracy to support Parliament and oppose the king and the Catholic Church [2].

When the Whig and Tory parties first emerged, the bourgeoisie and the new nobility still confronted feudalism, and as a result, the political struggle between these two parties had a distinctly class-based nature. The Whigs, who represented the new nobility, merchants, and financiers, not only engaged in parliamentary conflicts with the king and the Tories but also resorted to armed rebellion and assassination attempts[11]. During the Exclusion, the Tories published Robert Filmer's work 'On Patriarchy or the Natural Power of the King', which espoused the doctrine of the divine right of kings. Robert Braid, another Tory, wrote a history of England to express the views of Robert Filmer's work. In response, the Whigs proposed a balanced approach, advocating for the expansion of the Parliament's power and the limitation of the king's power, opposing despotism, and promoting the rule of law, leading to a heated debate with the Tories[11]. However, before the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs had not yet developed a unified and systematic political philosophy, and various theories differed among the Whigs. Certain Whigs believed that laws and constitutions perpetually evolved according to changing conditions. Some stated that England had been a limited monarchy since ancient times and that legislation assumed a mixed form. They believed the king ruled according to Parliament's advice. Some radical Whigs rejected the doctrine of the divine right of kings and presented the idea of "natural human rights"; however, it appeared less robust than Locke's thoughts. The "natural human rights" theory. During this time, the Whig political theories had even exhibited contradictions. One instance of such a contradiction was James Tyrrell's argument regarding private property and the people's right to resist [19]. Yet, almost all Whig theorists predominately highlighted that the subjects could only follow the legislature constituting the king, the House of Lords and the House of Commons, and the constitution itself. This was never the case with the king alone. Additionally, a monarch who menaced the constitution and the parliament could not sustain the trust of the people in him [11].

Most notably, the political theories of Whig individuals prior to the Glorious Revolution lacked precision, only indicating a general direction.

4.1.2.Key Figures and Thinkers Associated with the Whig Movement

In the course of the Exclusion Bill Crisis, the most prominent Whig leaders in the House of Lords were the likes of Shaftesbury, Holles, and Wharton, and mainly represented by Wensifen, Capel, and others in the House of Commons. The Whigs had more literary talent than the Tories, including Algernon Sidney, James Tyrrell, Henry Neville, William Petty, and others, as well as the great John Locke. William Petty argued that Parliament has the capability to annul existing laws based on historical records, pass fresh legislation, transfer existing private rights and property, legitimize unacknowledged children, and settle the problem of succession to the throne. Regarding the issue of royal succession, Algernon Sidney stated that Parliament has the power not just to restrict the authority of the king but also to determine who can ascend to the throne. This ideology supported the justification for the Whig's course of action to remove James II from the throne. James Tyrrell countered Robert Filmer's autocratic viewpoints but did not entirely elaborate on the aspects of rightful rebellion and disintegration of the government, nor did he scrutinize the customs of English history.

Although John Locke's opinions about natural law and rights are frequently considered a shield against despotism and the Glorious Revolution's Whig movement, in truth, Locke's outlook is more radical than the Whigs' revolutionary principles. The modern interpretation of John Locke’s political thought has recognized this difference between Lockean theory and Whig Revolution principles, and it has shifted from an image of Locke as the Whig apologist for 1688 to an understanding of Locke as fundamentally different and more radical than his Whig contemporaries [8].

Shortly after the dissolution of the Oxford Parliament in March 1681, Shaftesbury, the main Whig leader, was prosecuted and later acquitted by a jury. He then unsuccessfully attempted to organize an armed rebellion and subsequently fled abroad, dying in Holland in 1683 [1]. The Whigs lost their parliamentary position after the dissolution of Parliament in 1681 until the coup d'état in 1688 [11]. During the summer and autumn of 1682, several critical members of the Whig party plotted to assassinate Charles II and Duke John. After the plot was exposed, the Whig leaders Arthur Capell, Algernon Sidney, and William Russell were arrested and executed, significantly weakening the Whig Party.

4.1.3.Whig's Stance on Monarchy and Parliamentary Power

Despite opposing Duke John's succession to the throne and holding Parliament in high esteem, the Whigs were not against the British monarchy per se. According to the Whigs, Parliament, particularly the House of Commons, was the sole legitimate expression of people's will. They saw the King, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons, the legislative branch, as the ultimate authority. Although some Whigs claimed that Parliament had absolute power in the succession to the throne, they were mostly opposed to the King's and Parliament's absolute authority. Following the Thirty Years' Civil War, they aimed to establish a hybrid monarchy that would limit the powers of both the King and Parliament by bringing together the secular nobility and the democratic House of Commons under a representative system. The legislative power was to consist of the King, the nobility, and the lower house, while only the lower house would have the power of taxation, and the King would hold the executive power. They sought to abide by the constitutional tradition. Their ideal monarchy entailed separating and limiting powers to constrain the King. It would comprise the secular nobility under the aristocracy and the democratic lower house of Parliament through the representative system. The legislative power consisted of the King, the nobility, and the lower house, with the lower house solely responsible for taxation. Meanwhile, the executive power would be in the hands of the King [13]. The Whigs aimed to align with the constitutional tradition.

Nonetheless, there existed a minority of Whigs who embraced a more radical version of the mixed monarchy concept, that of a "king in parliament", in which the king was obliged to accept bills already passed by both houses of parliament. In addition, certain Whigs regarded the authority wielded by both houses of parliament as an organic by-product of the principle of mixed monarchy, whereby the king, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons all collaborated in a spirit of mutual agreement. Nevertheless, the more radical version of mixed monarchy did not have broad-based support, either among the political elite or within the Whig party. This was largely because the period of the Restoration still bore the marks of the Civil War and was not conducive to the acceptance of more extreme, radical political ideas [13]. Before the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs opposed the succession of a Catholic king more vehemently than the Tories. Still, on the issue of parliamentary power, there was no consensus among them.

4.2.The Historical Features of the Glorious Revolution

4.2.1.Overview of the Glorious Revolution and Its Causes

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was one of the most important events in English history. In this revolution, King James II stepped down, and the English Parliament invited William II and his wife, Mary, to become the new King and Queen. There was no more revolution. The revolution is known for its "bloodless" character, with "fewer disputes in the core areas of power." But the true face of history is that the English Revolution brought the struggle of Parliament against the king to a final victory. It completed the change of government in a bloodless way, making "Parliament Supremacy" and other constitutional principles that their predecessors fought for Finally established, opening a new era in human history, becoming an important milestone in the constitutional history of mankind. After a comprehensive analysis of the literature, we believe that there are two main reasons for this "bloodless" revolution, as follows:

4.2.1.1.The Dictatorship of the King in Politics

James II was constantly trying to expand his power and upset the balance of power between Parliament and the king. Before the Glorious Revolution, King James II was arrested for violating the former royal government's instituted restrictions on those not from the established Church and the Catholic Church. The law of the Apostolic office, appointing Catholics to the military, government, and the Church held important positions. It supported the appointment of Catholics to university posts, granting revoked decrees restricting the rights of non-conformists and Catholics [20]. James II also proclaimed the "divine right of Kings," arrested Protestants, and imposed authoritarian rule, leading to increased struggles with Parliament. This left the Whigs and Tories opposed to James II with the choice of whether the abolition of the monarchy could succeed. Violent social unrest is certain, about to "plunge the country into blood to bring their religion, their laws and their freedom back to the past the danger of escaping."

4.2.1.2.Contradictions between Religious Beliefs

We believe that the conflict between the Protestants and the king's Catholicism was also one of the main triggers of the Glorious Revolution. King James II vigorously promoted Catholicism in predominantly Protestant England, which caused resentment among the Protestant nobility and people.

4.2.2.Impacts on the English Monarchy and Parliamentary System

After analyzing the above two main reasons for the Glorious Revolution, please allow us to discuss the impact of the Glorious Revolution on the British monarchy and parliamentary system in this part, as follows:

4.2.2.1.The Birth of the Constitutional Monarchy and the Establishment of the Political Status of Parliament

The Glorious Revolution marked the gradual transition from monarchy to constitutional monarchy in England. The monarch is no longer a single-power individual, and the exercise of power by the monarch begins to be jointly supervised and constrained by law and parliament. At the same time, the monarch gradually became a ceremonial and symbolic role, and the real political jurisdiction of the country was transferred to Parliament, effectively following the common will of the old and new English aristocracy. Four of the seven coup makers of the Glorious Revolution were Whig leaders, representing the interests of the new aristocracy. The remaining three, the founders of the Tory Party, the hard-nosed barons, and the Bishop of London, were typical representatives of the old aristocracy. The coup by the seven old and new aristocrats showed that the Glorious Revolution was a compromise between the bourgeoisie and the feudal class. And the monarch lost real power at the same time. On the other hand, the political status of parliament has also been established, and parliament has obtained the power to make laws and other powers. Without the consent of parliament, the monarch cannot manage the country.

4.2.2.2.The Perfection of the Law, the Preservation of the Status of Protestantism

A search of the literature reveals that not only were the contents of the Bill of Rights improved, but the Act of Settlement of 1701 not only effectively resolved the question of succession to the throne but also prohibited Catholics from becoming Kings. As a direct result of the Glorious Revolution, this law effectively preserved Protestantism as the state religion in England.

4.2.3.Discussion of the Finding

From the perspective of the Glorious Revolution, we believe that it is necessary to comprehensively analyze the historical characteristics of the Glorious Revolution based on reading the previous literature and analyzing the political and ideological changes of the Whig Party from its historical characteristics. Therefore, allow us in this section to elaborate on the three historical characteristics of the Glorious Revolution that we have concluded, as follows:

4.2.3.1.The Establishment of the Main Position of the Parliament

After the Glorious Revolution, the new King William II and Queen Mary agreed to the passage of the English Powers Act, which we believe was not only an important sign of the limitation of the Crown's power, but also a sign of the supremacy of Parliament over the Crown in the British political system. In the revolutionary settlement of 1688-1689, the political elite achieved a smooth change of sovereignty from monarchy to parliament. Even more, the change was the result of both game and compromise between William, the Tories and the Whigs. Based on the real need for a revolutionary solution, the Tories had to Compromise with William and the Whigs, which established parliamentary sovereignty; Based on the need to preserve the structure of the hereditary monarchy, William and the radical Whig. The party also had to compromise, allowing William and Mary to become king and queen together, ostensibly continuing the hereditary succession, a retention-based system. The three parties used the phrase "James abdicated of his own accord" to disguise the fact that Parliament had deposed the king [4]. The political thought changes of the Whig Party before and after the Glorious Revolution were also closely related to this feature. Before the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs believed that Parliament should have a significant role in decision-making, including the power to make laws and the control of finances. After Glorious Revolution, we assumed that this belief will be further solidified. Therefore, we think that it was the establishment of the main role of Parliament that drove this change in the Whigs' belief in the importance of Parliament.

4.2.3.2.The King's Power is Constrained and Limited to a Certain Extent

We believe that this feature was not only the core goal of the Glorious Revolution but also promoted the development of the British monarchy from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy, which has important historical significance for the perfection of the British political system. The Glorious Revolution was the culmination of Britain's decades-long struggle between the King and Parliament. The final solution eliminated the "autocratic monarchy" and paved the way for the formation of a harmonious political situation Road. In the Middle Ages, when Europe was under Christian rule, it was dark Europe, no progress at all. Later, royal power gradually increased among the feudal lords and the new nobility with strong support, many countries in Europe established the autocratic rule of feudal Kings. Though [3]. Therefore, we learned that the changes of Whig political thoughts were also strongly connected with this historical feature by the angle of the historical significance behind this revolution.

4.2.3.3.Religious Tolerance

The Glorious Revolution was also a complete Protestant victory over Catholicism

The revolution. Religion is the foundation of English society, and church methods and institutions are conducive to morality and discipline. Law, church, and state are inseparable. The unity of religious belief is also the harmony of Britain Political formation provides ideological reassurance. Henry VIII's Reformation in the 16th century. It strongly promoted the formation of the British nation-state. The formation of the British nation-state established and consolidated in the struggle against Catholicism, anti-Catholicism is the English national sentiment [3]. Before the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs supported limited certain religious groups’ political participation. However, after the Glorious Revolution, this principle of religious toleration gained greater acceptance. Therefore, from the meaning behind this historical feature of religious tolerance, the Whigs realized after the Glorious Revolution that the degree of religious tolerance and the degree of support of the people were also inextricably linked. This was also an important factor that contributed to the change of political thought among the Whigs.

4.3.Whig's Response to the Glorious Revolution

4.3.1.Initial Reactions and Support from Whig Leaders

After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, most of the Whig leaders were satisfied with the results of the Glorious Revolution. Seven Tory and Whig barons jointly extended an invitation to Mary's husband, William, Prince of Orange of Holland, for armed intervention in England. William, who had come to defend "the religion, liberty, and property of the English people," was engaged in a war against France on the mainland and had been concerned about the situation in England but hoped to use English power and anti-French sentiment to continue the war against France [13]. And a stronger support for a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary sovereignty. The enactment of the Bill of Rights showed that the new King William II and the new Queen Mary accepted the limits of their power in Parliament, which also expanded the influence of the Whig Party in the British government to some extent.

4.3.2.Whig's Involvement in Shaping the New Political Landscape after the Revolution

We think that it is essential to summarize the specific changes in Whig political thought after the Glorious Revolution. After a comprehensive analysis of the literature we have collected, we found that the changes in Whig political thought are mainly concentrated in four aspects, as follows:

4.3.2.1.The Belief towards the Function of Parliament

The struggles of the 1680s and the experience of the Glorious Revolution strengthened the Whigs' conception of parliamentary power and their demand for limits on the power of the king. The Bill of Rights, the Mutiny Act, the Three Years Act, and the Tenure of Office Act were all the fruits of the efforts of lawmakers who limited their claims to the crown [13]. As we all know, the Glorious Revolution promoted the birth and establishment of the British constitutional monarchy, and the power of the king was restricted to a certain extent. The Glorious Revolution revealed the drawbacks of the king's despotism, and the Whigs began to oppose the absolute power and despotic rule of the monarch and advocated the co-governance of the monarch and parliament. After the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs began to support and firmly believe in constitutional monarchy. They believed that parliament was the highest organ of the state and that the handling of national affairs (such as legislation) should be through parliament rather than by the king himself. At the same time, they began to agree that the king should unconditionally abide by all decisions of Parliament in matters of state.

4.3.2.2.The Contractual Theory

The change in political thought of the Whig Party is closely related to the contractual theory. John Locke and Thomas Hobbes believed that people in the state of nature voluntarily give up some of their rights in exchange for the protection of the social order. We found that in the political thought of the Whig party, they have always held the view that "government is the product and medium of communication in the legal contract between the monarch and the people", and parliament represents the interests and wishes of the people. Thus, after the Glorious Revolution, the social contract theory provided a theoretical basis for the Whigs, who believed that the new monarch, William III, had accepted the power of Parliament and that a legal, social contract had been reached between the monarch and the people, thereby ensuring the rights and freedoms of the people.

4.3.2.3.Attitudes Towards the Monarchical Power

After the Glorious Revolution, the Parliament, representing the will of the people, passed the Bill of Powers, and the king could no longer exercise power on his own and would be subject to parliamentary oversight. In the process of the passage of this act, the Whigs supported the new monarch, William II, and the new Queen Mary to come to power. We believe that this attitude also shows that after the Glorious Revolution, the Parliament also began to support the constitutional monarchy, advocating that the power of the monarch should be supervised by Parliament, which is the highest authority of the state.

4.3.2.4.Religious Tolerance

After the Glorious Revolution, the Whigs became increasingly positive about religious tolerance. We believe that after the Glorious Revolution, the political atmosphere in Britain changed, and religious tolerance gradually became a policy guideline. The Whigs supported measures of religious tolerance to a certain extent, primarily out of concern for political stability.

It is worth noting, however, that the Whigs' religious tolerance was not absolute. Although they supported the tolerance of non-conformist religious beliefs to a certain extent, their main concern was to preserve the authority of the establishment and parliament. Whig leaders William III and Mary II issued the Toleration Act. The Whigs realized that if religious beliefs were tolerated, they could reduce religious tensions in the country, stabilizing the political situation and thus securing their power.

5.Conclusion

This study set out to accurately analyze the changes of Whig political thoughts before and it after the Glorious Revolution in a specific period (1679-1760). Based on the studies of past scholars on the Glorious Revolution and the Whigs, this paper further discusses the changes in the political thoughts of the Whigs before and after the Glorious Revolution in the specific period of 1679-1760, and comprehensively compares the main characteristics and aspects of the changes of the political thoughts of the Whigs through literature analysis. This paper provides a deeper insight into the relationship between historical events and political ideology. However, a limitation of this study is that the research method is only limited to the analysis of past literature, Not having diversity. Further on, we think that this study could also contribute to gaining more insights into how important historical events reshape political thoughts and affect historical progress.

References

[1]. Yingjuan Wu, “The story of the history of the Whigs and Tories in Britain”, Democracy & Science (2021): 47-51.

[2]. Honghai Li, “History and Myth: 800 Years of Legends”. Peking University Law Journal 27, No.6 (2015): 1594-1614.

[3]. Dahua Xu, “On the Influence of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ to the History of England”, Journal of Hubei University of Education, no.1 (2008): 83-84.

[4]. Li Hu, “Disagreement and Consensus: How England Opposed France's Claim to the Spanish Throne in 1700?”, Historical Review, no.4 (2022): 184-193+221.

[5]. H. Butterfield, The Whig interpretation of history (London: Bell and Sons, 1931)

[6]. J. G. A. Pocock, The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law: A Study of English Historical Thought in the Seventeenth Century: A Reissue With a Retrospect (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

[7]. R William, “The Origins of ’Whig’ and ‘Tory’ English Political Language”, The Historical Journal, no.2 (1974): 247-264.

[8]. Julia Rudolph, Revolution by Degrees: James Tyrrell and Whig Political Thought in the Late Seventeenth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 106-123, 158

[9]. Han Shen and Xincheng Liu, British parliamentary and political history(Nanjing: Nanjing University Press,1991), 193-199, 263-264.

[10]. Zhaoxiang Yan, “The evolution of the three main political parties in the UK”, History Teaching, No.4 (2012): 67-72.

[11]. Zhaoxiang Yan, History of the British political party system (Beijing: China Social Science Press, 1993), 6, 31-34

[12]. Zhaoxiang Yan, History of British Political Thought (Beijing: China Social Science Press, 2010)

[13]. Hengxiang Ma, “A Study of Early Whig Political Thought 1679-1714”, Nanjing University (2012)

[14]. Qisong Huang, “What is political thought - A normative interpretation of political thought”, CASS Journal of Political Science, No.6 (2012): 115-125.

[15]. Datong Xu, “Two Different Systems of Political Thought between China and the West”, CASS Journal of Political Science, No.3 (2004): 23-30.

[16]. Zehua Liu, General history of Chinese political thought-treatise (Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2014)

[17]. Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S, “Transforming Qualitative Research Methods: Is It a Revolution?”, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 24, No.3 (1995): 349–358.

[18]. Jinyuan Liu, “On the Rise of Party Politics in Modern Britain”, Journal of Historical Science, no.11 (2009): 83-91.

[19]. Hengxiang Ma, “A Review of the Ideas of British Whig Theorist James Tyrrell”. Chinese Journal of British Studies, 2011: 288-301.

[20]. Chuanxu Yuan, “Discussion of the Glorious Revolution”, Book House (2007): 52-58.

Cite this article

Xiong,Y.;Li,M. (2024). Viewing the Change of Whig’s Political Thoughts by the Glorious Revolution (1679-1760). Communications in Humanities Research,29,48-59.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yingjuan Wu, “The story of the history of the Whigs and Tories in Britain”, Democracy & Science (2021): 47-51.

[2]. Honghai Li, “History and Myth: 800 Years of Legends”. Peking University Law Journal 27, No.6 (2015): 1594-1614.

[3]. Dahua Xu, “On the Influence of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ to the History of England”, Journal of Hubei University of Education, no.1 (2008): 83-84.

[4]. Li Hu, “Disagreement and Consensus: How England Opposed France's Claim to the Spanish Throne in 1700?”, Historical Review, no.4 (2022): 184-193+221.

[5]. H. Butterfield, The Whig interpretation of history (London: Bell and Sons, 1931)

[6]. J. G. A. Pocock, The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law: A Study of English Historical Thought in the Seventeenth Century: A Reissue With a Retrospect (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

[7]. R William, “The Origins of ’Whig’ and ‘Tory’ English Political Language”, The Historical Journal, no.2 (1974): 247-264.

[8]. Julia Rudolph, Revolution by Degrees: James Tyrrell and Whig Political Thought in the Late Seventeenth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 106-123, 158

[9]. Han Shen and Xincheng Liu, British parliamentary and political history(Nanjing: Nanjing University Press,1991), 193-199, 263-264.

[10]. Zhaoxiang Yan, “The evolution of the three main political parties in the UK”, History Teaching, No.4 (2012): 67-72.

[11]. Zhaoxiang Yan, History of the British political party system (Beijing: China Social Science Press, 1993), 6, 31-34

[12]. Zhaoxiang Yan, History of British Political Thought (Beijing: China Social Science Press, 2010)

[13]. Hengxiang Ma, “A Study of Early Whig Political Thought 1679-1714”, Nanjing University (2012)

[14]. Qisong Huang, “What is political thought - A normative interpretation of political thought”, CASS Journal of Political Science, No.6 (2012): 115-125.

[15]. Datong Xu, “Two Different Systems of Political Thought between China and the West”, CASS Journal of Political Science, No.3 (2004): 23-30.

[16]. Zehua Liu, General history of Chinese political thought-treatise (Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2014)

[17]. Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S, “Transforming Qualitative Research Methods: Is It a Revolution?”, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 24, No.3 (1995): 349–358.

[18]. Jinyuan Liu, “On the Rise of Party Politics in Modern Britain”, Journal of Historical Science, no.11 (2009): 83-91.

[19]. Hengxiang Ma, “A Review of the Ideas of British Whig Theorist James Tyrrell”. Chinese Journal of British Studies, 2011: 288-301.

[20]. Chuanxu Yuan, “Discussion of the Glorious Revolution”, Book House (2007): 52-58.