What Factors Influence the Meaning of Smiling Emoji in WeChat Conversation

Jihao Tong1,a,*, Chuming You2

1Faculty of Humanity and Social Science, University of Nottingham, Ningbo, 315100, China

2Guangdong Country Garden School, Guangdong, 528312, China

a. 2964649388@qq.com

*corresponding author

Abstract: This paper explores the semantic and pragmatic meaning of smiling emoji occurring with text in Chinese online communication and discovers what factors might have an effect on context meaning. Five top popular smiling emojis from WeChat have been selected to set scenes that are most common in daily life. Based on the multimodal analysis framework, how people use emojis in the text will be analyzed to discover representational, interpersonal, and textual features of emojis. It is found that visual graphic features, age, relationship between interlocutors, and structure can all influence the meaning of emoji. People use different ways to use emoji to achieve their goals and hidden purposes. In general, emojis often occur at the end of the text, substituting or assisting words to achieve speech acts and promote emotional feeling.

keywords: Multimodal analysis, pragmatics, speech acts, semantic, emojis

1.Introduction

Online communication has infiltrated daily life greatly with the rapid development of technology and the massive application of mobile equipment. Unlike oral communication, online communication lacks non-verbal elements such as gestures, facial expressions, and phonetic cues. Even though, sociolinguistics has paid significant attention to this new field due to its unique and special properties [1]. Online communication devised new non-verbal cues, such as capitalization for strong emotions and continuous punctuation marks to express various feelings or emphasis, to help communicate and transmit feelings [2]. Emoji, as another newly invented non-verbal cue, is widely used as well.

Emojis are colored graphic icons and have relatively direct meanings [3]. which originated in Japan and are successors to emoticons. Due to its multimodal and non-verbal features, emojis usually occur with text. According to Yang and Liu [4], both semantic and pragmatic meanings assist and complement conversation. However, in many cases, semantic meaning mismatches with the hidden speech acts. This phenomenon happens quite often in China's online communication. Various platform has adapted emojis and modified some emojis. For example, Weibo and WeChat platforms (the two biggest online communication platforms) have different versions of smiling faces. As a result, different people, based on their ages, familiarity with the online environment, and other factors, will use and interpret the same emojis in different ways, which will lead to misunderstanding. One typical exciting phenomenon is the use of a smiling face. The young generation will regard it as a way to show sarcasm, while older people will assume it as a kind and friendly smile. Thus, in this research, we would like to discover what factors influence the meaning of emoji. We adopted a multimodal analysis framework to study from three perspectives: ideational (semantic), interpersonal (pragmatic), and textual meaning. Questionnaires are made to discover different age groups’ perceptions and actual use of 5 typical smiling emojis in WeChat. Firstly, the overall pattern of usage will be quantitively analyzed, and then several detailed occasions will be further analyzed.

2.Literature Review

In the current online digital communication environment, the usage of emojis has become increasingly prevalent. It expands the way people transmit information, such as expressing emotions, attitudes, and hidden meanings. Different emojis might share the same sentiments and feelings to assist sentence construction, while the same emoji sometimes will be adapted for different circumstances [5]. In addition, the combination or selection of emoji’s type and token is complex, which can result in achieving different semantic and pragmatic meanings for the interlocutor’s needs. Thus, emoji provide a huge database for sociolinguistics to study. Plenty of previous researchers have studied how users use emojis in different ways to achieve their intended speech acts [6]. For example, Liu and Yang have studied the influence of different emoji attaching to the same text [2-4]. The text is “A driver on the highway go the wrong way and said ‘I think it is feasible’.” When there is no context to help understand the circumstances, emojis assist in constructing the meaning. When the emoji describes a sweating face with an ashamed smile, the text emoji cooccurrence reflects that the speaker had a fluke mentality and did not think what he had done was improper. When the emoji is a grey and white cartoon-style skull, the text’s meaning then switches to showing how the speaker feels sorry and regret about what he had done. Besides from their semantic function, different emoji also shows different pragmatic function such as expressing different emotions or achieving personal goals.

Considering the special feature of emoji that it provides both semantic and pragmatic meaning to the discourse, the multimodal analysis framework is the most suitable one to analyze the meaning. In almost all kinds of communication methods, meaning cannot merely be expressed verbally. It is also communicated through multiple semiotic modes [7]. Multimodal discourse analysis then provides a proper way to see how multiple modes of communication, such as images, sound, or other factors, interact for communication purposes. This framework helps to capture the complexity by studying how different modes interact and convey the whole meaning, and it recognizes the importance of each mode in influencing the interpretation of the conversation. In online communication, it suits emojis as well, which is a typical visual graphic image and can help people to have a more comprehensive understanding of discourse. This framework was built based on Halliday’s systemic-functional theories and expanded to paralinguistic and non-linguistic aspects by Kress and Leeuwen [8]. According to Kress and van Leeuwen, a metafunctional analysis framework has the ability to discover how different modes work together to make meaning with a top-down frame [9]. There are three metafunctions working together to create overall meaning: ideational function, interpersonal function, and textual function.

According to Kress and van Leeuwen, ideational meaning represents’ the world around and inside people’[9]. Various semiotic modes have their features, and lexical and grammatical functions to relate to each other to create meaning. For example, some images can be classified into analytical ideational meaning that the picture mainly emphasizes the parts-wholes relationship. From creating this spatial relationship, protagonists will be more salient. Thus, simply speaking, ideational meaning mainly focuses on the image itself and, in this research, focuses on the visual feature of different emojis and their semantic meaning. Liu and Yang pointed out that emojis can be regarded as pictograms, which provides visual alternative or supplement for text [3,4]. In addition, emojis can be categorized into different groups such as iconic (smiles, sad faces) and symbolic such as star signs. In this research, only smiling iconic emojis are taken as an example.

In addition, semiotic modes have to make relationships and achieve goals with viewers. Certain social interactions and relationships are achieved by using different modes for different pragmatic functions. For example, Kress and van Leeuwen said gaze as a semiotic mode creates or decreases the interaction between gaze producer and other interlocutors by simply showing direct visual sights or not [9]. According to Herring and Dainas [10], there are 6 pragmatic functions of graphic symbols: mention, reaction, tone modification, action, riff, and narrative sequence. People use emojis to achieve speech, act to make relationships or achieve personal needs. From another perspective, people will accommodate other interlocutors by imitating their speech style, such as using different emojis. However, when the receiver interprets emojis incorrectly, misunderstanding happens, and original goals cannot be achieved. It focuses on the structure and organization of text and semiotic modes for textual meaning. Ai et al. found that emoji typically occur with text, usually following the whole text [11]. While, in some situations, emoji will substitute words or phrases. The way text and emoji co-construct sentences influence the overall meaning as well, such as adding tone and irony.

3.Methodology

3.1.Data collection

The data were collected from the questionnaire designed on the website (https://www.wjx.cn).

Participants were divided into two age groups: teenagers (aged fourteen and twenty-five) and middle-aged (aged between forty-five and fifty-nine). A pilot study was designed to choose the most commonly used emojis to represent “smiling” emojis. After the pilot study, five emojis were chosen. Their original meanings were defined as: “grin,” “chuckle,” “smile,” “drool,” and “cool” in the WeChat emoji. However, the participants had different understandings of the emojis. Based on the pilot study, another questionnaire was designed to discover what factors may influence the meanings of the “smiling” emojis.

3.2.Questionnaire design

Overall, there are ten questionnaires per set were selected. The website has conducted some simple statistics on the answers. Excel was used for further analysis to calculate the mean and frequency of using the five emojis and their functions under different circumstances.

The questionnaire questions were divided into three parts according to the multimodal discourse analysis: ideational, interpersonal, and textual meaning. As for quantitative purposes, the first part consists of five questions, and the second part has two questions. The third part had set several circumstances followed by choices of “smiling” emoji and the surveyees also needed to choose the meanings behind their choices. It should be mentioned here that the third part is short answer questions that must be analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. It includes both interpersonal and textual meanings to study the pragmatic and semantics meaning. The content of the first part was to rate different sentimental aspects of each emoji to study whether different group’s participants’ general perceptions towards the emoji were positive or negative. Thus, the dimensions of emojis are designed with two positive and three negative states. The score 0 means feel none of this emotion, while five means the highest intensity. An example is shown below:

Figure 1: An example of questions in the first part of the questionnaire.

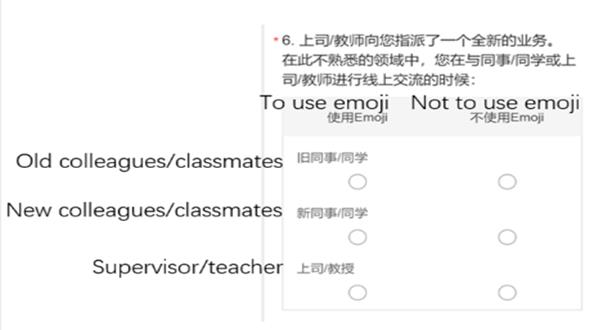

The second part was multiple choice questions to examine under certain given circumstances. whether or not the participants will use emojis to communicate with others. This part was set to analyze different participants’ attitudes about using emojis in formal or casual contexts. An example is shown below.

Figure 2: An example of questions in the second part of the questionnaire.

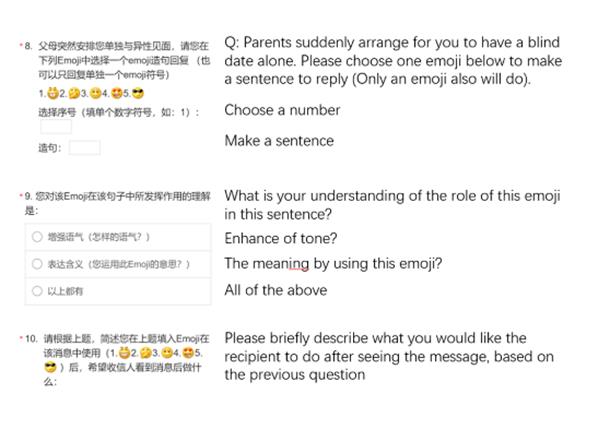

The third part was short-answer questions. The content was to sort out and induce the main opinions of the emoji they chose by examinees’ short answers. Based on different situations, different questions are set for participants to answer, which are social context, learning context, job context, family context, and public context. This part investigated the examinees’ perception and purposes for the emoji’s use.

An example is shown below:

Figure 3: An example of questions in the third part of the questionnaire.

4.Result

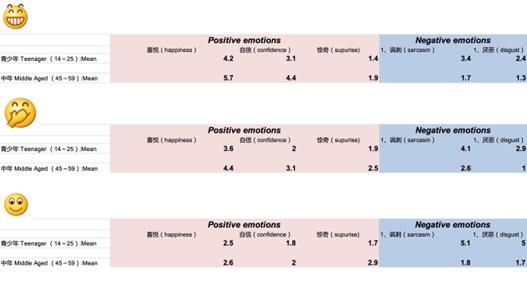

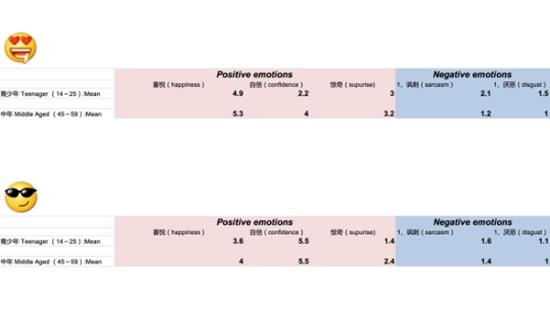

Figure 4: The result of the first part of the questionnaire.

As the data in Figures 1, 2, and 3 show, there is a typical pattern revealed in the part 1 answers. The middle-aged group has a relatively high score in feeling positive emotions, while teenagers feel more negative emotions, such as sarcasm and disgust.

For example, as Figure 4 shows, the two sets have different understandings of emoji 1. Teenagers gave a relatively high score to “happiness.” However, the meaning of sarcasm was also high at 3.4 points. As for the middle-aged, most of them agree that the choice “happiness” does take a proportion of the emotion for 5.7 points. Then, the emotion of confidence followed as 4.4 points. The middle-aged group scores much higher in positive emotions while having a quite low score in feeling negative emotions.

The same phenomenon happens in the second emoji. Teenagers gave a score for sarcasm of 4.1 points, which was much higher than the points of the middle-aged, which was only 2.6 points. The third emoji showed excellent discrimination on negative emotion. Both “sarcasm” and “disgust” were chosen at a high rate by teenagers, while middle-aged people chose the opposite scores. The two groups have similar results in the fourth and fifth emoji, but they still reveal the general pattern.

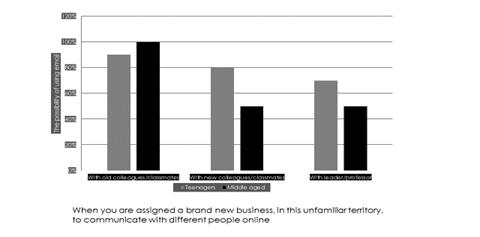

Figure 5: The result of the second part of the questionnaire.

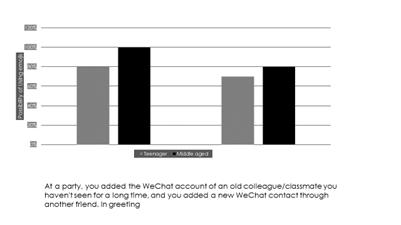

Figure 6: The result of the second part of the questionnaire.

As Figure 5 shows, when facing a particular working/learning condition, teenagers had a lower proportion of using emojis to connect with new classmates, and their professors, as middle-aged people, chose to use emojis more when contacting old mates. In the second situation shown in Figure 6, it can be seen that the percentage of middle-aged people who had the will to use emoji is higher than teenagers as well.

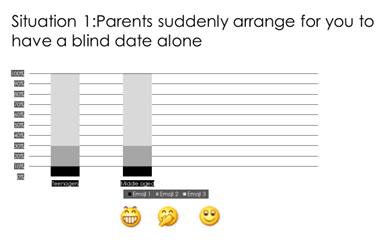

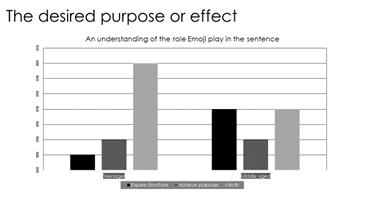

Figure 7: The result of the third part of the questionnaire.

Figure 8: The result of the third part of the questionnaire.

Table 1: Desired purpose or effect interviewed in the questionnaire.

| The desired purpose or effect | Middle-aged Group | Lighten the atmosphere | Happy and cheerful | Happy | I’m happy as well | Don’t arrange it | Resistance | Understanding |

Table 1: (continued).

| Teenager Group | Persuade to quit | No need to have a date | Understand my difficulties | Let the other person understand their resistance | Cancel the meeting | Cancel the blind date | Because they are elders, smiling faces may be more friendly to them, but they can also express speechless and surprised hearts |

Figure 7 suggests that the proportion of the emoji’s selection was the same. However, the meaning is quite different. It can be seen in Figure 8 and Table 1, that both teenagers and middle-aged group agree with the usage of emoji to express emotion and achieve purposes. At the same time, the actual use and interpretation is quite different. Most of the teenagers in this experiment refused to join the blind date, but they still chose the “smile” emoji as replies to their parents. As for the middle-aged, most of them decided to reply in a positive way and use smiling emojis to show original meaning. That is showing happiness in Figure 9 and Table 2.

Figure 9: The result of the emoji choosing.

Table 2: Phrases made according to the questionnaire.

| Phrases they made | Middle-aged Group | Yes Yes! | Eager to go | For fun | Emoji 4 | Happy! | Emoji 4, Great! | Teenager Group | Yeah! | Ok! | Yes! Yes! Yes! (Obsessed) | Wow, thank you! I’m deeply moved, I was dying to go there. Emoji 4 | For Real? | Wow!!!Great! (drooling) |

In situation 2, only four emoji:1,2,4,5 were chosen to be replied. The proportion of the usage of emoji 3 of teenagers and the middle-aged were the same. Teenagers’ use of emoji 5 is triple that of middle-aged people, but for emoji one, they were half of the data of middle-aged people. As for emoji 2, it was only chosen by middle-aged people. When the participants were asked to fill in their attitudes toward this situation, they all showed a positive attitude through the four emojis mentioned. The analysis of situations 3 and 4 is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Emoji and its meaning.

5.Analysis

According to the multimodal analysis framework’s ideational meaning, visual features will have vague emoji meanings. Although all these “smiling” emoji were originally designed as a positive feature indicating happiness and friendliness with merely slight differences, young people tend to assign a novel use to the emoji, which conveys negative meanings such as sarcasm and speechlessness [12,13]. This might be attributed to platform differences. Each platform will make the emoji’s graphic features different by modifying color or facial feature details. Unlike letters, which can only be interpreted as letters regardless of form, emojis are open to interpretation. Tigwell and Flatla found significant differences in interpreting the sentiment and intensity of facial emojis between Android and Apple emojis [14]. Miller demonstrated that there is 25% disagreement on sentiment in emoji rendering, and there is great difference in describing emoji’s semantic meaning [15]. In this experiment, the graphic feature can also influence emoji’s semantic meaning and people’s perception. For example, one possible factor that influences the third emoji’s meaning is that the eyes look down, and there are too many whites of the eyes, so it seems contemptuous. At the same time, the smile does not cause the muscles near the eyes to contract, so it feels like a fake smile. As for the first emoji, it exposes teeth and bends eye muscles, so it got a relatively high score in positive emotions. Jing demonstrated that the sender’s age affects the perception of emojis when facing ambiguous statements because they might have more comparisons between different versions of emojis, so young senders were more likely to see sarcasm [16].

Discourse meaning is not only interpreted by the image itself. Context, the relationship between sender and receiver, and pragmatic functions influence interpretation. According to Kelly and Watts [17], people prefer emojis to maintain or end conversations or build harmonious relationships. Gullberg also claimed that emojis could enhance emotion intensity, show receipt of the message, and manage conversational feelings (serious, friendly) [18]. Generally speaking, people use emojis to express emotion, achieve speech acts, and increase informality. In part 2, it is evident that older people prefer emojis in almost every condition, while young people refuse to use them when facing serious or new conditions. Both old and young senders tend to use more emojis in close relationships regardless of potentially ambiguous statements. Emojis help create an informal and casual environment, and the hidden speech act may be the will to let the receiver perceive. In serious conditions, young people prefer not to use emojis to show that they are reliable and not taking the job seriously. In part 3, situation 1, although young people wanted to refuse their parents and show bad emotions, they still used smiling emojis to reply. This is probably due to the accommodation theory that people intend to speak the way they assume interlocutors will have. This way, young people can express their feelings and maintain a harmonious relationship with their parents. The hidden pragmatic speech act is the will to cancel the blind date even though their parents might not interpret that deeply. Middle-aged group people, primarily use emoji to maintain relationships and increase informality.

In situation 2, the two groups use emojis to connect emotionally with their friends to show excitement and happiness. The usage of exclamation mark work aligns with emojis to increase emotion intensity. What can be mentioned here is the extra pragmatic function of the middle-aged group. They additionally show grace and respect to their friend, which is unseen in the young group. In situations 3 and 4, it can be concluded that different emojis might share the same sentiments and feelings to assist sentence construction. In contrast, the same emoji sometimes will be adapted for other circumstances and speech acts [2,5]. Textual meaning of emoji focuses on the structure of emoji and text. In most cases, emojis appear behind the whole text to express emotion or add meaning to the discourse. The system helps construct the overall purpose.

6.Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper discovered what factors influence emoji's semantic and pragmatic meaning and how people use it to achieve their purposes. This study might help explain some basic phenomena in current Chinese online communication and help people understand how smiling emojis create ambiguity. Thus, people can reduce misunderstanding and decline disharmony in communication. The questionnaire showed the pattern of different age groups’ frequency and preference of using emojis. Although there is limited data to generalize the emoji-using situation, it can still reveal some features about the usage. Visual graphic elements, age, relationship between interlocutors, and structure can all influence the meaning of emoji. People use different ways to use emoji to achieve their goals and hidden purposes. However, the social and cultural background is not included in this research, which can show how these factors influence people’s identity. The understanding of online communication and new things is also hard to measure in study.

References

[1]. Baym, N. K. (1996). Agreements and disagreements in a computer-mediated discussion. Research on language and social interaction, 29(4), 315-345.

[2]. Riordan, Monica A., and Roger Kreuz. (2010). “Cues in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Corpus Analysis.” Computers in Human Behaviour 26(6): 1806–1817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.008

[3]. Moschini, I. (2016). The "Face with Tears of Joy" Emoji. A Socio-Semiotic and Multimodal Insight into a Japan-America Mash-Up. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business, (55), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i55.24286

[4]. Yang, X., & Liu, M. (2021). The pragmatics of text-emoji co-occurrences on Chinese social media. Pragmatics: Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association, 31(1), 144-172.

[5]. Hakami, S. A. A. (2017) "The importance of understanding emoji: An investigative study." Research Topics in HCI: 1-20.

[6]. Wantong, SUN. (2021). Analysis of Pragmatic Functions of “Smile” Emoji in Chinese WeChat Communication Between People of Different Ages. Sino-US English Teaching. 18. 10.17265/1539-8072/2021.08.001.

[7]. Jones, R. (2012). Discourse analysis : A resource book for students (Routledge English Language Introductions). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

[8]. Halliday, Michael A. K.(1994) An Introduction to Functional Grammar (2nd edition). London: Edward Arnold.

[9]. Kress, Gunther, and Theo V. van Leeuwen, (2006): Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (2nd Edition). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203619728

[10]. Herring, S.C., & Dainas, A.R. (2017). "Nice Picture Comment!" Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

[11]. Wei Ai, Xuan Lu, Xuanzhe Liu, Ning Wang, Gang Huang, Qiaozhu Mei (2017). Untangling emoji popularity through semantic embeddings." Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media. Vol. 11. No. 1.11(1), 2-11. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v11i1.14903

[12]. R. Zhou, J. Hentschel, N. Kumar. (2017). “Goodbye text, hello emoji: Mobile communication on WeChat in China” Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI '17), Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2017), pp. 748-759,

[13]. Gabriele de Seta, G. (2018). Biaoqing: The circulation of emoticons, emoji, stickers, and custom images on Chinese digital media platforms. First Monday, 23(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i9.9391

[14]. Tigwell, G. W., & Flatla, D. R. (2016). "Oh that's what you meant!": Reducing emoji misunderstanding. In MobileHCI '16 Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, MobileHCI 2016 (pp. 859-866). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2957265.2961844

[15]. Miller, Hannah, Jacob Thebault-Spieker, Shuo Chang, Isaac Johnson, Loren Terveen, and Brent Hecht. (2016). “‘Blissfully Happy’ or ‘Ready to Fight’: Varying Interpretations of Emoji.” In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2016). Palo Alto, CA: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

[16]. Cui, J. (2022). Respecting the Old and Loving the Young: Emoji-Based Sarcasm Interpretation Between Younger and Older Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 897153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897153

[17]. Kelly, Ryan, and Leon Watts. (2015). “Characterising the Inventive Appropriation of Emoji as Relationally Meaningful in Mediated Close Personal Relationships.” Paper presented at the Workshop on Experiences of Technology Appropriation: Unanticipated Users, Usage, Circumstances, and Design, Oslo, 20 September.

[18]. Gullberg, Kajsa. (2016). “Laughing Face with Tears of Joy: A Study of the Production and Inter- pretation of Emojis among Swedish University Students.” BA thesis, Lund University.

Cite this article

Tong,J.;You,C. (2024). What Factors Influence the Meaning of Smiling Emoji in WeChat Conversation. Communications in Humanities Research,29,69-81.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baym, N. K. (1996). Agreements and disagreements in a computer-mediated discussion. Research on language and social interaction, 29(4), 315-345.

[2]. Riordan, Monica A., and Roger Kreuz. (2010). “Cues in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Corpus Analysis.” Computers in Human Behaviour 26(6): 1806–1817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.008

[3]. Moschini, I. (2016). The "Face with Tears of Joy" Emoji. A Socio-Semiotic and Multimodal Insight into a Japan-America Mash-Up. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business, (55), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i55.24286

[4]. Yang, X., & Liu, M. (2021). The pragmatics of text-emoji co-occurrences on Chinese social media. Pragmatics: Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association, 31(1), 144-172.

[5]. Hakami, S. A. A. (2017) "The importance of understanding emoji: An investigative study." Research Topics in HCI: 1-20.

[6]. Wantong, SUN. (2021). Analysis of Pragmatic Functions of “Smile” Emoji in Chinese WeChat Communication Between People of Different Ages. Sino-US English Teaching. 18. 10.17265/1539-8072/2021.08.001.

[7]. Jones, R. (2012). Discourse analysis : A resource book for students (Routledge English Language Introductions). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

[8]. Halliday, Michael A. K.(1994) An Introduction to Functional Grammar (2nd edition). London: Edward Arnold.

[9]. Kress, Gunther, and Theo V. van Leeuwen, (2006): Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (2nd Edition). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203619728

[10]. Herring, S.C., & Dainas, A.R. (2017). "Nice Picture Comment!" Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

[11]. Wei Ai, Xuan Lu, Xuanzhe Liu, Ning Wang, Gang Huang, Qiaozhu Mei (2017). Untangling emoji popularity through semantic embeddings." Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media. Vol. 11. No. 1.11(1), 2-11. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v11i1.14903

[12]. R. Zhou, J. Hentschel, N. Kumar. (2017). “Goodbye text, hello emoji: Mobile communication on WeChat in China” Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI '17), Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2017), pp. 748-759,

[13]. Gabriele de Seta, G. (2018). Biaoqing: The circulation of emoticons, emoji, stickers, and custom images on Chinese digital media platforms. First Monday, 23(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i9.9391

[14]. Tigwell, G. W., & Flatla, D. R. (2016). "Oh that's what you meant!": Reducing emoji misunderstanding. In MobileHCI '16 Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, MobileHCI 2016 (pp. 859-866). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2957265.2961844

[15]. Miller, Hannah, Jacob Thebault-Spieker, Shuo Chang, Isaac Johnson, Loren Terveen, and Brent Hecht. (2016). “‘Blissfully Happy’ or ‘Ready to Fight’: Varying Interpretations of Emoji.” In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2016). Palo Alto, CA: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

[16]. Cui, J. (2022). Respecting the Old and Loving the Young: Emoji-Based Sarcasm Interpretation Between Younger and Older Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 897153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897153

[17]. Kelly, Ryan, and Leon Watts. (2015). “Characterising the Inventive Appropriation of Emoji as Relationally Meaningful in Mediated Close Personal Relationships.” Paper presented at the Workshop on Experiences of Technology Appropriation: Unanticipated Users, Usage, Circumstances, and Design, Oslo, 20 September.

[18]. Gullberg, Kajsa. (2016). “Laughing Face with Tears of Joy: A Study of the Production and Inter- pretation of Emojis among Swedish University Students.” BA thesis, Lund University.