1. Introduction

Prior to modern times, the fundamental purpose of art in the Western world was to advance religion, Christianity especially [1, 2]. After establishing its orthodox status in the first several centuries following the once prevalent belief in Roman Gods and Goddesses, Christian artists gradually developed a system of abstract representation to keep a comfortable distance from the pagan past, as well as to maintain harmony between the aniconic doctrine and the desire for visual presentation [3]. By abandoning the techniques of shading, modeling, and perspective in art practice, a style of flatness dominated the figure representations in Medieval art [4]. However, as the economy and knowledge thrived in Italy and other parts of Europe due to the navigational trade and scientific progress in anatomy, natural history, optics, etc., artists once again adopted a method of careful observation of nature and developed a naturalistic representation in art from Renaissance times onwards [5].

This paper aims to compare and contrast how religious figures are represented in paintings from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. By using the Holy Infant as an archetype, the author examines the differences and similarities between the infant with other saints in Madonna Enthroned (by Duccio di Buoninsegna) and the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints and Angels (by Sandro Botticelli), both of which share the same theme of enthroned Virgin and Child, and seek for the different significances they embodied respectively in the representational paradigms.

2. Studies on the two paintings

While the Maestà Altar created by Duccio and his assistants was completed in 1311, the altarpiece made by Botticelli was not finished until the late fifteenth century. During this period, painting techniques, themes, and styles had undergone significant change.

As a master based in Tuscany in the 13th-14th century, Duccio was skilled at integrating abstract forms from Byzantine paintings, the sensibilities from contemporary Gothic art, and illusionism from antiquity [6]. The representation in his works, therefore, vacillates between the mystical holiness of idealized forms and the aesthetic appeal of naturalistic expressions.

The works of Botticelli, on the other hand, based every detail on naturalistic representation. By emphasizing the realness of the content above the nobility of the mediums and the icons, the humanity of these religious figures inspires resonance inside the minds of the viewers.

2.1. Madonna Enthroned by Duccio

The theme of Maria Regina started to exist in the thirteenth century when the Marian cult first emerged and began to flourish from then on. Christianity has been infused with a strong feminine aspect [7]. After a military victory over Florence, the city of Siena took Virgin Mary as its patron and commissioned the altarpiece in 1308 as a token of jubilation [8].

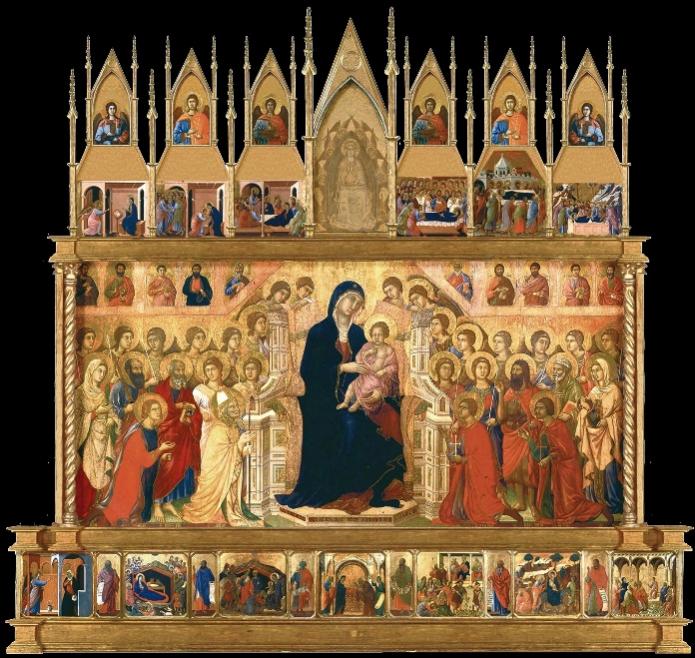

Figure 1: Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna enthroned, center of the Maestà Altar. 1308–11. Tempera and gold on wood, 213 × 396 cm. Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena. Accessed from https://www.analisidellopera.it/duccio-di-buoninsegna-maesta-di/.

2.1.1. The Premature Holy Infant

The holy infant in Maestà seems to have more extraordinary intelligence than a mortal neonatal. Sitting backward in Virgin Mary’s arms, he is looking outside the altarpiece plane with timorous gestures, as if there are as many people watching him as inside the painting, and the admiring eyes from all orientations are making him bashful and reserved. His left hand is holding one side of his clothes to cover his genitals, and the other hand is on top of his chest as if he is soothing himself. It seems that he already has human ethics and sympathy in his mind. The head of the infant takes up one-sixth of his total height, which is another feature of premature in his age considering that the average proportion of an infant's head and body is 1:4, and the ratio decreases as a man grow up. The holy infant’s hair is as thick and strongly curved as an adult's, with a clearer hairline and no lanugo. The color of his hair and halo is brighter than any other figure in the painting. The muscles cover his bones fittingly without any spare flesh (baby fat). Every gesture of his is out of consideration rather than instincts, and in the meanwhile, the premature physical features suggest his inborn extraordinary as well as humanity.

The rosy color of the infant's soft clothes is a symbol of the human body and incarnation. The Early Renaissance artists gradually started to use the color pink to depict healthy faces and hands. According to the humoral theory, the blood is associated with a sanguine nature and is also believed to consist of small proportional amounts of the other three senses of humor in the body. The extensive use of the color on the holy infant is an emphasis on the blood beneath the flesh, therefore the humanity embodied in Christ. On the other hand, the color is also a reminder of the flower carnation, whose botanical name "dianthus" means "flower of God" in Greek. This kind of flower is believed to first existed when the Virgin wept in the Crucifixion, and the color is therefore a premonition of Christ's Passion.

2.1.2. Other Elements in the Hierarchy

The contrast of figure sizes and colors makes the viewers' attention fall easily on the Virgin and Child. The size of the figures could be divided into three levels, which in the meanwhile reflects the hierarchical structure in the religious world. The Virgin and Child are the largest in the composition. The Virgin has almost four times the body size of the characters around her, and the Child has the same size head compared to the surrounding adults. In the background are ten other saints of smaller size than any other characters, suggesting a rather distant position in both spatial and hierarchical sense. The colors of the Virgin and Child as well as the throne are vividly contrasting against each other. The bright and hard material of the throne separates the main characters from others. The light-colored draperies on the throne provide a perfect foil for the dark blue velvet of the Virgin's robe, which sets off for the Child's light rosy swaddling clothes as well.

Besides the main characters, twenty angels and twenty saints are depicted in the rectangular panel. While the Virgin and Child are sitting right on the central axis, the angels and saints are distributed on both sides in a very symmetrical way. Every figure could be found in its counterpart in the symmetric position of the composition, with its gestures, expressions, the orientation of faces, and genders echoing with each other. The Christian world seems to unfold along the axis of the Virgin and Child, as well as the almighty God.

The architecture-like division in the background not only puts the less important saints into corners to save more space for the main characters but also forms an ascending tendency over the head of the Virgin and Child, suggesting the existence of the visually absent God. In this sense, the angels with wings are like flying down directly from above, whereas the saints seem to have more distance to heaven. While the first two and the backmost lines in the image are mostly saints, the angels take up the relatively central spaces in the composition, announcing for higher hierarchy and more detached positions than the saints from the secular world.

The angels have got similar facial features and hairstyles, which are serene and asexual. The saints, on the other hand, vary from each other in costumes, hairstyles, ages, genders, and religious pieces held in their hands. While the details of the variations of the saints enrich the viewers' visual experience, the allegory of the Tower of Babel strikes into viewers' minds too. After Yahweh confounds the united people's speech, they have finally found a way to unite again, with both the viewers and the figures inside the painting, under the power of Christian love.

2.1.3. The Inviting Quality and the Call of Worship

As the center artwork of the altarpiece, it aims to bear the gaze of Christian believers and other people on earth. A sense of invitation is embodied in the altarpiece formed by details that function upon the viewer's subconsciousness. The reserved expression of the infant seems to be a response to the viewers’ pilgrims outside the painting plane, as well as the Virgin’s demonstrating gestures to show us the body of the infant. The admiring crowd of angels and saints in the painting, especially the four kneeling figures in the foreground, functions as imitation objects and creates an atmosphere of gratification and reverence, leading a viewer to indulge in the religious solemn and joy.

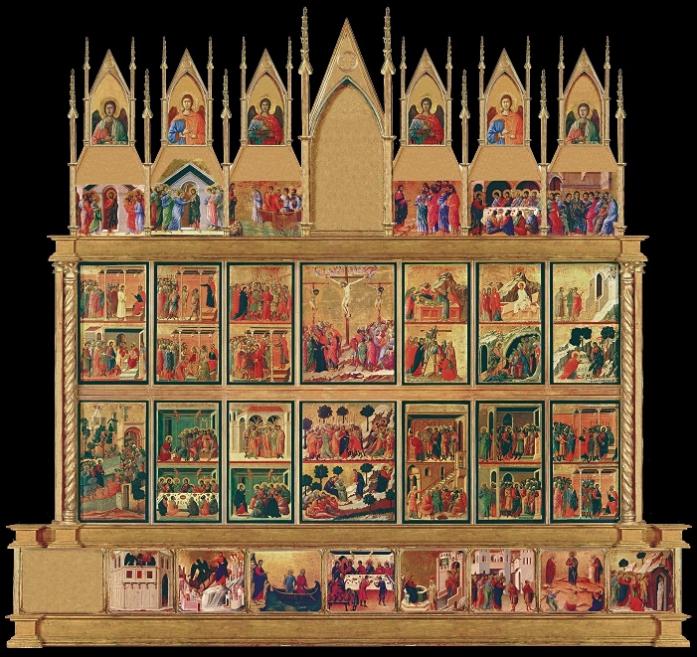

Figure 2: Front and back of the Maestà Altar. Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena. Accessed from https://www.analisidellopera.it/duccio-di-buoninsegna-maesta-di/

The gilding on the clothes and the background is due to a characteristic technique in that period when the altarpieces are traditionally decorated with golden leaves in Tuscany. As the light inside a church is dim, the gilding altarpiece could be brightened easily with a single beam of light and therefore manifest itself from the darkness and be watched clearly by people. The strong contrast between the resplendent artwork and the obscure space containing it invites the eyes to focus on the altarpiece and pay tribute to the light, the sign of God.

2.2. The San Barnaba Altarpiece by Botticelli

As another altarpiece in the church, the painting of Botticelli in the Pala di San Barnaba did not have golden leaves to accentuate its splendor. Rather, the vibrant sentiments of the three-dimensional full figures are what capture the viewers’ attention initially. As a result, it was more convincing that the power of Christianity is with us since it employed more naturalistic representation to weave the theme's holiness into a more mundane and ordinary environment close to our lives.

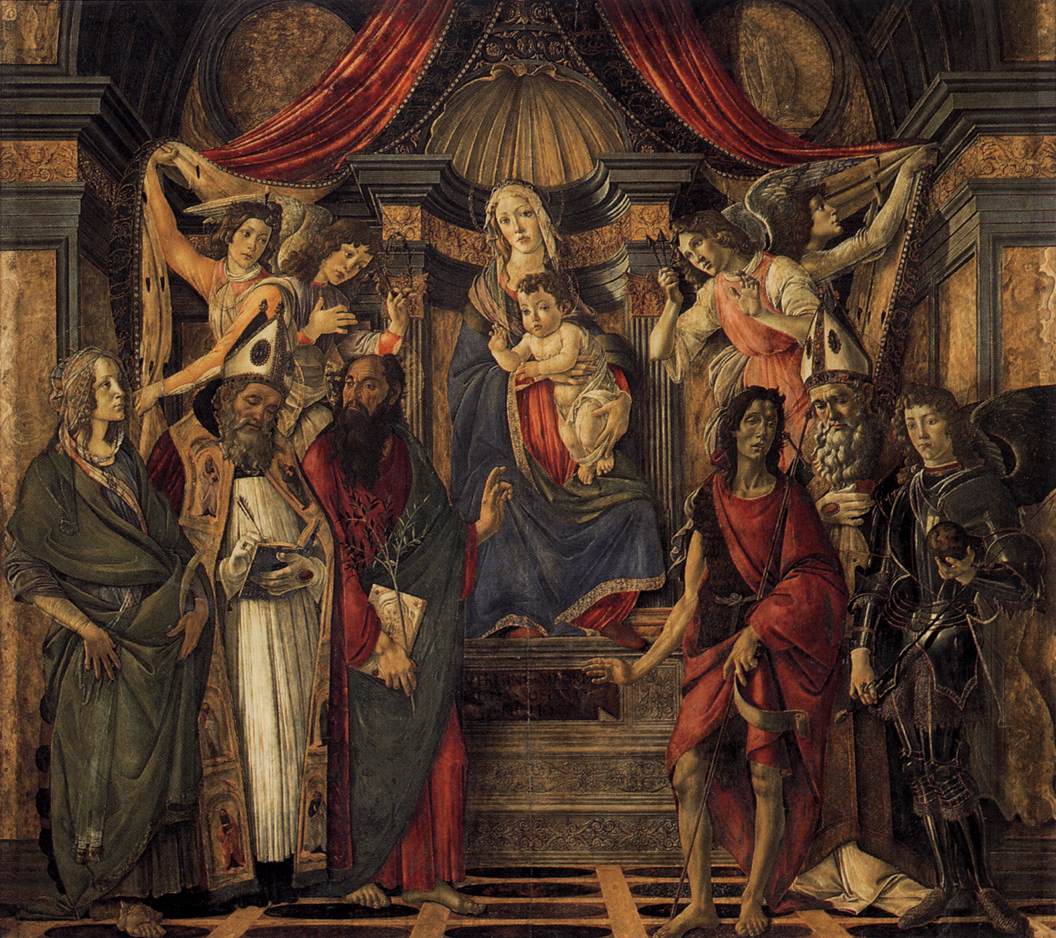

Figure 3: Sandro Botticelli, Madonna, and Child Enthroned with Saints and Angels (The San Barnaba Altarpiece), c. 1486-87. Tempera on panel. 268 × 280 cm. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Accessed from https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/b/botticel/3barnaba/10barnab.html

2.2.1. The Infant Christ Rather Than Christ in Infant Body

The holy infant in Botticelli’s artwork seems more carefully grounded in reality. Enclosed safely in the Virgin’s hands, the infant is trying to put his weight forward and reach something that draws his interest, just like any other curious infant in the mundane world. (Though actually, the raising right hand of him is in the attitude of blessing, Christ seems to be unaware of the meaning of his gesture at this moment.) The exposed body parts are not paid attention to nor even noticed by the baby compared to Duccio's works. The physical features of the infant are represented in a naturalistic way, too. The head of the infant takes up about one-fourth of his body length like a normal human baby. The prominent frontal bone, the eye size of nearly a grown-up on a little face, and the baby fat on his face, limbs, and torso suggest the anatomical progress in Renaissance times when the artists were able to capture the characteristic features of different age groups. The dark brown hair of the infant has different levels of thickness, which is thin and mostly hair ends near the forehead and gradually grows thick towards the back of the head. Unlike the paintings from early times, there are reflected lights in the shadow of the skin, suggesting a sense of volume as well as the smoothness of the skin. Despite the almost transparent halo behind his head, the holy infant grows and acts just like any other innocent infant in the world, and reminds people more of the infant period of Christ rather than Christ's soul embodied in an infant.

2.2.2. Allegories Hidden in the Painting

Unlike the Virgin in Maestà, whose hair and feet are discreetly hidden, the Virgin in Botticelli's painting has her hair fallen down her shoulders naturally and left foot out of the robe to firmly support the infant's weight. Comparing the different hair colors of the Virgin and Infant, the account of the Father is revealed to the minds of the viewers. From the left above in the composition where comes the main light source for the painting, it falls gently on the faces of the Virgin and Child, and it seems like the thing that the infant is interested in and wants to get close to is the light from above.

The throne where the Virgin sits is totally above eye level (the horizon), suggesting the heavenly positions of the Virgin and Child, as well as the angels on the same level. On the third step of the throne inscribed lines from Dante’s Commedia in Italian, which read "Vergine, Madre, Figlia Deltuo Figlio (Virgin, Mother, Daughter of thy Son)” [9]. The revelation of the curtains by the angels forms an ascending tendency over the Virgin and Child’s heads like in Maestà, which is another allusion to the main characters' holiness.

What is worth noting is the left hand of St. Barnabas (the figure closest to the throne on the left, with a book and an olive branch in his right hand), which is the only thing interrupting the views of the motif of the Virgin and Child. The gesture of this hand expresses amazement or wonder in Christian iconography, but why is the scene of Virgin and Child throned a wonder? Maybe something could be told from other details. The architectural decorations in the background, a pair of roundels and a shell-like structure on the central axis connecting to the throne, have an outline resembling the genital organs inside a female body, where humanity is recaptured in it since the Lost of Paradise [10]. The metaphorical maternal space depicted in the painting is a container and the environment for the infant to grow, as the church space for God’s people [11]. However, the nails and the crown of thorns held by the two angels near the throne are a presage of Christ’s Passion, which is one of the explanations for the compassionate expression on the Virgin’s face.

2.2.3. The Deity in Naturalistic Representation

Drawing inspiration from both biblical text and the works of his predecessors, Botticelli constructed a scene from Christian allegories with convincing illusion. The realistic portrayal of visual art makes people more willing to believe in God compared to the literal preaching and the personal interpretation of abstract imagery. Only the images are naturalistic enough may evoke the viewers’ resonance with the icons and perfuse our souls into the naturalistically rendered objects.

3. Conclusions

One of the most interesting differences between the two works is the infant's varying levels of physical and psychological development. The goal of the figure's portrayal before the Renaissance was to create a mystical child who was innately extraordinary and to entice others to approach him and worship beneath his illumination with incontestable faith. As in Renaissance art, the newborn appears to be simply concerned with what he is currently fascinated about and appears to be unconscious of the impending suffering or the eyes of others on him. As a result, the infant's vulnerability and courage as a corporeal God are made apparent to people's hearts. There are, however, some parallels between the two pieces as well. The presence of the angels and saints implies a connection between Heaven and the earthlings. The symmetrical composition of the architectural structures and the distribution of figures is a traditional approach to conveying the constancy and stateliness of this sacred scene. The motif of the enthroned Virgin and Child emphasizes the importance of the Virgin, the recapture of humanity in her body, and the protection of the child in her arms. While the holiness of the religious figures is preserved through a similar strategy for composition, the sense of superiority is substituted by the brilliance of humanity.

References

[1]. De Gruchy, J. W. (2001). Christianity, art, and transformation: Theological aesthetics in the struggle for justice. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Elsner, J. (1995). Art and the Roman viewer: the transformation of art from the pagan world to Christianity (p. 160). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3]. Kogman-Appel, K., & Meyer, M. (Eds.). (2009). Between Judaism and Christianity: art historical essays in honor of Elisheva (Elisabeth) Revel-Neher. Brill.

[4]. Meyer, B. (2016). The Icon in Orthodox Christianity, Art History and Semiotics. Material Religion, 12(2), 233-234.

[5]. Seznec, J. (1995). The survival of the pagan gods: The mythological tradition and its place in Renaissance humanism and art (Vol. 38). Princeton University Press.

[6]. Keyes, G. (1982). The Influence of Neoplatonism on Art from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance (Doctoral dissertation).

[7]. Wegner, Susan E. (2001). The Sixteenth Century Journal 32, no. 1: 315–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/2671503.

[8]. Benko, Stephen. (2004). The Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Pagan and Christian Roots of Mariology. Netherlands: Brill.

[9]. Watts, Barbara J. (1998). “THE WORD IMAGED: DANTE’S ‘COMMEDIA’ AND SANDRO BOTTICELLI’S SAN BARNABA ALTARPIECE.” Lectura Dantis, no. 22/23: 203–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44858251.

[10]. Balthazar, P.M. The Mother-child Relationship as an Archetype for the Relationship between the Virgin Mary and Humanity in the Gospels and the Book of Revelation. Pastoral Psychol 55, 537–542 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-007-0073-2.

[11]. Thomas, R. F. (1999). Reading Virgil and his texts: Studies in intertextuality. University of Michigan Press.

Cite this article

Ding,Y. (2023). Changes in Religious Figure Representation: A Study of the Holy Infant in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Communications in Humanities Research,3,343-349.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 1

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. De Gruchy, J. W. (2001). Christianity, art, and transformation: Theological aesthetics in the struggle for justice. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Elsner, J. (1995). Art and the Roman viewer: the transformation of art from the pagan world to Christianity (p. 160). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3]. Kogman-Appel, K., & Meyer, M. (Eds.). (2009). Between Judaism and Christianity: art historical essays in honor of Elisheva (Elisabeth) Revel-Neher. Brill.

[4]. Meyer, B. (2016). The Icon in Orthodox Christianity, Art History and Semiotics. Material Religion, 12(2), 233-234.

[5]. Seznec, J. (1995). The survival of the pagan gods: The mythological tradition and its place in Renaissance humanism and art (Vol. 38). Princeton University Press.

[6]. Keyes, G. (1982). The Influence of Neoplatonism on Art from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance (Doctoral dissertation).

[7]. Wegner, Susan E. (2001). The Sixteenth Century Journal 32, no. 1: 315–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/2671503.

[8]. Benko, Stephen. (2004). The Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Pagan and Christian Roots of Mariology. Netherlands: Brill.

[9]. Watts, Barbara J. (1998). “THE WORD IMAGED: DANTE’S ‘COMMEDIA’ AND SANDRO BOTTICELLI’S SAN BARNABA ALTARPIECE.” Lectura Dantis, no. 22/23: 203–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44858251.

[10]. Balthazar, P.M. The Mother-child Relationship as an Archetype for the Relationship between the Virgin Mary and Humanity in the Gospels and the Book of Revelation. Pastoral Psychol 55, 537–542 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-007-0073-2.

[11]. Thomas, R. F. (1999). Reading Virgil and his texts: Studies in intertextuality. University of Michigan Press.