1. Introduction

In the history of all musical instruments, the pipe organ is the most complexly constructed, the largest, and the most expensive [1]. In addition, pipe organs, as purely religious instruments, were generally built in conjunction with churches or opera houses [2]. As a result, there is no definite limit to the specifications of a pipe organ; instead, the size of the organ is determined by the size and affordability of the church or opera house itself. With its high volume and whole tone, the pipe organ is suitable for playing profound and sacred religious music in a solemn atmosphere. In medieval Europe, almost all churches in small towns had large and small pipe organs used to play music during religious celebrations. Being the organist of a famous cathedral was a proud honor for musicians. The pipe organ is prominent, up to 10 meters in size, with more than 30,000 pipes and seven keyboards that produce a majestic sound. Romain Rolland described in detail in "Jean-Christophe" how listening to organ music is like a baptism of the soul [3].

Early organ performances typically featured two people. Since then, as the scale of the pipe organ expanded, it developed into a more complex internal mechanical structure because the massive size of the pipe organ made it impossible to press the keyboard of the pipe organ by human power alone. The development of medieval organ music is closely related to the development of medieval religion. The development of medieval religion can be said to have played an irreplaceable role in pipe organ music's development, flourishing, and prosperity.

2. The development of the pipe organ and medieval church music

The history of the origin of the pipe organ, in addition to the mythological story of the "flute of the god of wood" in ancient Greek mythology, is related to a musical instrument used by the Romans in Egypt called the "Hydraulos" [4]. This is a kind of pipe organ called "Wasserorgel," invented by Ktesibris, an engineer from Alexandria in Ancient Greece, who invented a water-pressure-controlled windchest, which can be regarded as the earliest pipe organ. Archaeologists have also found clay models of water-pressure-controlled windchests in the ruins of Carthage. In addition, the remains of some real instruments have been found near Budapest, Hungary. At that time, pipe organs were mainly used by the nobility.

In 757, during the Byzantine period, Constantine Copronymus V presented an organ cast in gold and silver to the Frankfurt king of Europe [5]. This event influenced the spread of the pipe organ from Eastern Rome to the Western region. Then, between the 6th and 9th centuries, the pipe organ spread to Spain, Germany, France, and other areas where European countries were located. However, the early church believed that the beautiful and innocent souls of human beings could be awakened only through vocal music and that instrumental music corrupted people's minds and intoxicated them with worldly emotions. As a result, the pipe organ was rarely used in the original church music, and most musicians who were proficient on the various instruments at that time were minstrels.

As shown in Figure 1 below, pipe organs were small, and even portable pipe organs existed.

Figure 1: Pipe organ in 9th century psalm illustration.

After that, with the further expansion of the Church and the popularization of the idea of the existence of God, a new shift in musical aesthetic thought occurred. Some Church musicians believed that the pipe organ had an air of emptiness and mystery, of ambiguity, which, accompanied by the tremendous acoustic scale of the pipe organ, could produce an effect of incomparable splendor and that, in such a stirring atmosphere, it could calm one's mind and bring one closer to God in thought. Under the influence of new ideas of musical aesthetics, the pipe organ naturally became the medium for a new sense of faith. For example, Saint Cecilia, who often appears next to the organ in paintings, represents a story of martyrdom for the faith [6]. The Church proved that in addition to the human voice, there was a need for the perfect vehicle capable of expressing affection for God, and the pipe organ, which could convey praise with a louder voice, was used in the Church liturgy.

With the formal introduction of the pipe organ into the Church, the production techniques improved dramatically, and its form and timbre became more and more in line with religious ideas. Between the 13th and 14th centuries, the range of large pipe organs was expanded, and a pipe organ in Halberstadt, Germany, in 1361 required ten people to operate it simultaneously. By the 15th century, the pipe organ's range had expanded, and its sound quality had plateaued. In his book Music in Western Civilization, Paul Henry Lang refers to the organ's history. He states, "In Byzantium, the organ was very clearly a secular instrument, but as it came to the West, the status and form changed, from a secular instrument to a truly ecclesiastical one."[7]

Thus, the combination of the history of the pipe organ and medieval church music shows that the development of medieval church music had a profound influence on the development of the pipe organ. In addition, as the church's power increased, the pipe organ's shape became more extensive, which meant the improvement of the pipe organ's manufacturing technique and the transformation from a secular instrument to a religious one.

3. The development of the pipe organ and medieval church music education

At the end of the 11th century, the ecclesiastical reform movement represented by the Cluny movement achieved essential results. In particular, the clergy (bishops, archbishops, and abbots) were separated from the three major aristocratic classes by having a say in clerical appointments. The victory in this struggle further consolidated the power of the Church, which rose to a height unprecedented in history, especially as nations were required to seek papal assent on essential matters. The theological theory that the Church had unearned power became a political reality, and the Church became the representative of a greater power over the kings of the West. At this time, schools were mainly founded by the Church, teachers were mainly from the Church, and many of the most prominent educators of the time were clergy members, such as the Abbot of Bemus and Jarrow, Bede (672-735), and the principal of York Minster School, Alcuin (735-804). Education itself was full of theological overtones. Christian schools were almost the only educational institutions of the time. Professor Aldrich, a specialist in the history of education at the University of London, also states in his book A Short History of Education in England that the control of education by the Church is a fundamental point in English history [8].

Music education has provided a variety of venues for the training of professional musicians and for the active training of church singers who serve the Church according to its religious needs. The Church invited teachers to teach music to the clergy, among other subjects, including musicianship, keyboard skills, voice, and improvisation. St. Ambrose's "Guide to Music" suggests that music education helps people introduce and communicate with God, helping the entire universe reach true fundamental harmony [9]. This reverence for God was a significant reason why music education at the time was focused on the formation of clergy, and music education activities were limited to seminaries, monasteries, and monastic schools. Meanwhile, the Church continued to invest in music education, greatly influencing the development of music and music education in Europe at the time and the history of organ music.

In the Middle Ages, most books were written by monks [10]. The seven subjects monks were required to learn were called the seven liberal arts. The first three, grammar, rhetoric, and logic, were considered the keys to knowledge, while the last three, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music, were more practical [11]. Saint Thomas (1225-1274) called music the crown of the seven arts, the noblest modern science [12]. Music was considered a rational discipline in the Middle Ages rather than a product of imagination or emotion. Boethius (Ancius Manlius Severinu, 475-525), a famous medieval music theorist, categorized music into three types. These three musical genres are as follows [13]:

(1) Cosmic music, which he categorized into three types. It studies the correspondence between music and the constellations and seasons.

(2) Human music. Against the former, we study the relationship between music and the proportions of the human body and the harmony of the mind and body as a microscopic order in the human body.

(3) Music of Instruments. It refers to music practiced by three kinds of instruments: stringed instruments that produce sound by tension, wind instruments and accordions that produce sound, and percussion instruments that produce sound.

The rise of church power in the Middle Ages led to the development of church music education, and the aesthetics of religious music influenced the history of the pipe organ, along with music education at the time. From the time of the Romano-French chant until the early 15th century, the music that remained throughout the Middle Ages was almost exclusively vocal. The human voice takes center stage from the reverent ritual music of monasteries to the dainty court songs, the polyphonic motets of the religious and secular, and the sophisticated aristocratic madrigals. What is clear, however, is that instruments accompany some vocal works. For example, the cantus firmus and the contratenor, the facing voice. Another positive is that instrumental music relies on vocal music in various forms. For example, the instrument's involvement in religious worship music began with the alternating performance of the Alternatium by the singer and the pipe organ at the pipe organ missa. In creating instrumental music for the pipe organ at that time, the chant was sustained on long notes, forming the so-called fundamental melodic voice, or tenor. The discounts or superius, or high melodic voice, on the other hand, freely moved to faster notes; this improvisational use of faster notes is known as diminution. These developments are related to medieval church music education and aesthetic ideology.

The situation of music education in the Middle Ages and the ideology of musical aesthetics at the time, mentioned in the preface, also contributed to the development of the pipe organ. By the late Middle Ages (early Renaissance), Conrad Paumann and his unusual method of composing pipe organ music, the auxbourdon method, had become one of the hallmarks of pipe organ music [14].

4. The development of the pipe organ and the "Codex Faenza" score collection

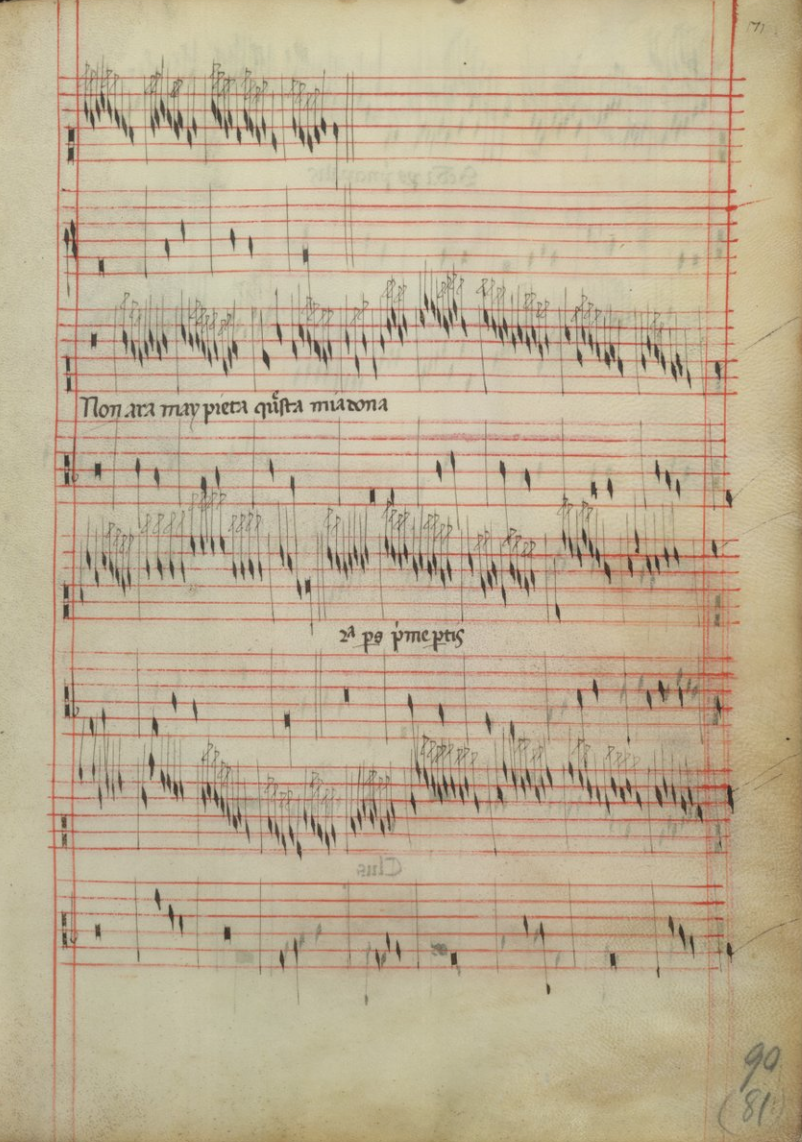

The most extensive extant collection of instrumental music from the Middle Ages is the Codex Faenza, an invaluable source of medieval instrumental music with many adaptations of 14th-century French and Italian music.

The original layer of the Codex Faenza is a 14th-century vocal adaptation. As shown in Figure 2 below, the original layer contains eight lines of music per page, recorded using "mensural notation" (black and red notes). The musical compositions in the second layer of the Codex Faenza have been hypothesized to be songs from the Lucca region in 1467-73. The second level of the Codex Faenza is transcribed in white quantitative notation, an Italian notation for the organ. The notation consists of two melodic lines connected by bar lines. The bass part of the melody is on the bottom, and the discantus part is on the top.

Figure 2: Faenzai 117. Kódex [15].

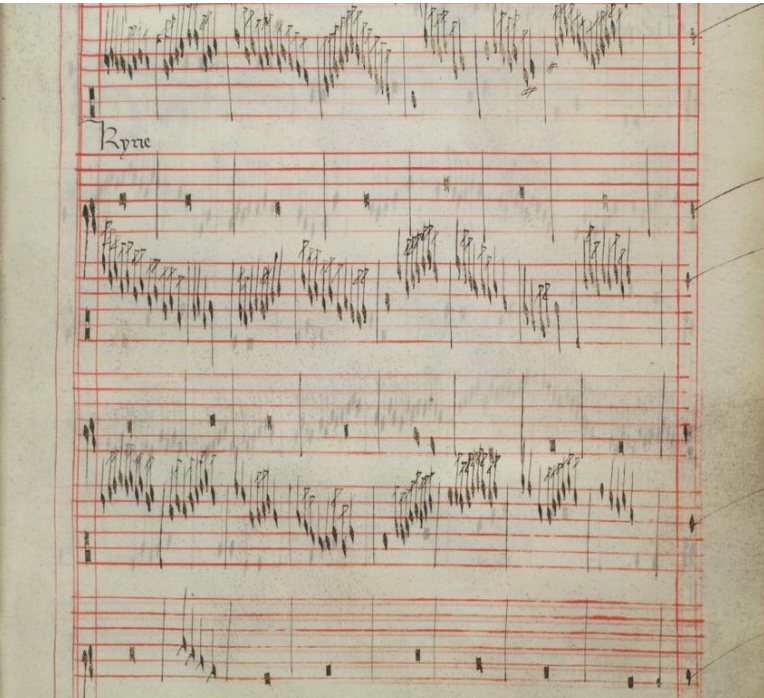

In its systematic and unified organizational structure, the Codex Faenza is not a collection of haphazardly selected pieces in its systematic and unified organizational structure. Both parts begin and end with pipe organ adaptations of the Mass. The first part contains only ballades and virelai of French origin, leading through the Kyrie and ending with the Deo Gratias. The second part is similar in structure. It begins with the Kyrie, followed in the middle by a ballata and madrigal of Italian origin. It includes the Gloria and ends with the Deo Gratias. The melodic chant on which the Mass is based is derived from the Missa Cunctipotens genitor Deus, the first extant pipe organ Mass. The ancient practice of alternating pipe organ and choir for each movement of this Ordinary of the Mass dates to the 11th century, with examples surviving into the 19th century, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Kyrie - Cunctipotens Genitor Deus.

5. Conclusions

The use and development of the pipe organ is a two-way street between the pipe organ and medieval religion. In terms of medieval church music development, most instruments originated outside of Europe. For example, the vielle is a Middle Eastern instrument, the lute is an Arabic instrument, and the harp is related to some instruments from Asia and Africa. As such, instruments were used more for the secular music of the time and spread between different countries and peoples, along with social influences such as war and trade. Because of this, the "purity" of instrumental music mainly was not recognized by the church of the time. However, the pipe organ originated in ancient Greece and has been the instrument of choice for the upper classes for hundreds of years. The use and development of the pipe organ in Europe reflects the longstanding cultural influence of ancient Greece and Rome on European civilization. In addition, many pipe organists were clergy and members of the courtly aristocracy. For example, in the introduction, Saint Cecilia is not only a symbol of the pipe organ in church music but also a noblewoman. This dual status of aristocratic and ecclesiastical players is one of the reasons why the pipe organ is recognized as such.

The development of the pipe organ in the Middle Ages provided essential conditions for the spread and development of the pipe organ in Europe. The emergence and spread of the pipe organ in Europe is linked to religion. The appearance of the Codex Faenza, a collection of instrumental music, and the emergence of clerical composers like Conrad Paumann as mature pipe organ players indicate the critical influence of medieval church music on the development of pipe organ music.

Thus, the medieval pipe organ was an outlet for identity and cultural identification. The pipe organ traces the culture of ancient Greece and Rome to Europe, with the dual status of nobility and church clergy. Using the pipe organ signaled the medieval church and the public's exploration of ancient Greek and Roman culture in Europe against the backdrop of the player's dual status as a nobleman and church cleric. The medieval church also saw the use of the pipe organ as a way of spreading religion and displaying power. The pipe organ was also an inevitable choice for the medieval church to strengthen its religious and cultural public identity. Because of this, conditions such as medieval cultural background, historical context, social development, and political needs influenced the use of the pipe organ in Europe and the interaction between the pipe organ and medieval religion.

References

[1]. Yearsley, D. (2012).Bach's feet: the organ pedals in European culture. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Ginsberg‐Klar, M. E. (1981). The archaeology of musical instruments in Germany during the Roman period. World archaeology, 12(3), 313-320

[3]. Rollings, B. (2020). From pipe organ to pianoforte: the practice of transcribing organ works for piano with a critical study of Ceś ar Franck's Preĺ ude, fugue et variation, op. 18 and Johann Sebastian Bach's prelude and fugue in D major, BWV 532.

[4]. Plitnik, G. R. (1992). Organothymedia: Reflections on the enjoyment of the pipe organ. Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 13(1), 1-10. “......by the Greek god Pan, who fashioned his pan pipes from Syrinx, a lovely water nymph who had beentransformed into a hollow reed.”

[5]. Williams, E. V. (1988). Macht und Klang: Tönende Automaten als Realität und Fiktion in der alten und mittelalterlichen Welt. “......757 as a gift from the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V Copronymus to Pepin...”

[6]. Murray, G. (1939). Saint Cecilia and Music. The Downside Review, 57(1), 77-81.

[7]. Lang, P. H. (1967). The enlightenment and music. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 1(1), 93-108. “In general, medieval musicography followed antiquity in that its explanations always referred to individual invention.”

[8]. Aldrich, R. (2005).Lessons from history of education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich. Routledge.

[9]. Thornton, R. (1879). St. Ambrose: His life, times, and teaching. Society for promoting Christian knowledge.

[10]. Begley, R. B., & Koterski, J. W. (Eds.). (2009). Medieval education. Fordham Univ Press.

[11]. Parker, H. (1890). The seven liberal arts. The English Historical Review, 5(19), 417-461.

[12]. Torrell, J. P. (2005). Saint Thomas Aquinas: The person and his work (Vol. 1). CUA Press.

[13]. Chadwick, H. (1981). Boethius, the consolations of music, logic, theology, and philosophy.

[14]. Minamino, H. (1986). Conrad Paumann and the evolution of solo lute practice in the fifteenth century. Journal of musicological research, 6(4), 291-310.

[15]. Plamenac, D. (1951). Keyboard music of the 14th century in codex Faenza 117. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 4(3), 179-201.

Cite this article

Zheng,L. (2024). A Two-Way Choice: The Medieval Pipe Organ and the Development of Medieval Church Music. Communications in Humanities Research,33,94-99.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yearsley, D. (2012).Bach's feet: the organ pedals in European culture. Cambridge University Press.

[2]. Ginsberg‐Klar, M. E. (1981). The archaeology of musical instruments in Germany during the Roman period. World archaeology, 12(3), 313-320

[3]. Rollings, B. (2020). From pipe organ to pianoforte: the practice of transcribing organ works for piano with a critical study of Ceś ar Franck's Preĺ ude, fugue et variation, op. 18 and Johann Sebastian Bach's prelude and fugue in D major, BWV 532.

[4]. Plitnik, G. R. (1992). Organothymedia: Reflections on the enjoyment of the pipe organ. Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 13(1), 1-10. “......by the Greek god Pan, who fashioned his pan pipes from Syrinx, a lovely water nymph who had beentransformed into a hollow reed.”

[5]. Williams, E. V. (1988). Macht und Klang: Tönende Automaten als Realität und Fiktion in der alten und mittelalterlichen Welt. “......757 as a gift from the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V Copronymus to Pepin...”

[6]. Murray, G. (1939). Saint Cecilia and Music. The Downside Review, 57(1), 77-81.

[7]. Lang, P. H. (1967). The enlightenment and music. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 1(1), 93-108. “In general, medieval musicography followed antiquity in that its explanations always referred to individual invention.”

[8]. Aldrich, R. (2005).Lessons from history of education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich. Routledge.

[9]. Thornton, R. (1879). St. Ambrose: His life, times, and teaching. Society for promoting Christian knowledge.

[10]. Begley, R. B., & Koterski, J. W. (Eds.). (2009). Medieval education. Fordham Univ Press.

[11]. Parker, H. (1890). The seven liberal arts. The English Historical Review, 5(19), 417-461.

[12]. Torrell, J. P. (2005). Saint Thomas Aquinas: The person and his work (Vol. 1). CUA Press.

[13]. Chadwick, H. (1981). Boethius, the consolations of music, logic, theology, and philosophy.

[14]. Minamino, H. (1986). Conrad Paumann and the evolution of solo lute practice in the fifteenth century. Journal of musicological research, 6(4), 291-310.

[15]. Plamenac, D. (1951). Keyboard music of the 14th century in codex Faenza 117. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 4(3), 179-201.