1.Introduction

The Tale of Genji serve an irreplaceable position not only in the Japanese literacy world but also the whole world literacy palace. Since it was first written by Murasaki Shikibu, it gained popularity among the aristocrats in the Heian period and had been rewritten in different versions among different period. In the work, the author focuses on the media of The Tale of Genji between Muramachi period and Edo period and tried to anchor on the audience that these two different media faced to show the different of times and the development of the technology. It might remove the shadow of the calligraphy and painting technique applied in Muramachi period and Edo period.

2.The background media of The Tale of Genji

In the long history of humans, each civilization has bred its own unique representative of the national characteristics of the literary works. Just as the pivotal role that The Dream of the Red Chamber played in the Chinese literature history, The Tale of Genji also occupies an irreplaceable position in the history of Japanese literature. “Written in the early eleventh century by the noblewoman and lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu” [1], The Tale of Genji” is a unique depiction of the lifestyles of high courtiers during the Heian period” [2]. It recounts the romantic life of Hikaru Genji and describes the customs of the aristocratic society of the time, aiming to entertain the Japanese court of the eleventh century and fill the patch of boredom in the aristocrat's daily life.

Owing to the popularity that it gained among the mass and enduring classicism composed by highly complex grammar and the modifying or rephrasing of classic poems according to the context needs, it has been rewritten and republished numerous times since its creation at the peak of the Heian period. Among these copies, even though “the original manuscript written by Murasaki Shikibu no longer exists”, there are “numerous copies, totaling around 300 according to Ikeda Kikan, exist[ing] with differences between each” [3]. Under this circumstance, The Tale of Genji has been expressed in different forms in terms of different eras, and its media of delivering and printing also changed to meet the various demands of different audience. For instance, at the very beginning of Tokugawa period, media that are often known for exquisite and elaborated took up a large proportion of the spread, such as manuscripts, illustrated scrolls and albums, for they were primarily read by the aristocrats who enjoyed a great deal of money and time to polish the details of belongings and to pursue the quality of life. By the contrast, the Inaka Genji, which is mainly for the middle strata, characterized by delivering more storytelling information and plots on a limited amount of paper to economize on ink and paper. In this way, it is possible to reflect the changes and progress of the times in respect of the characteristics of different media.

3.The details of the Album from Muromachi period

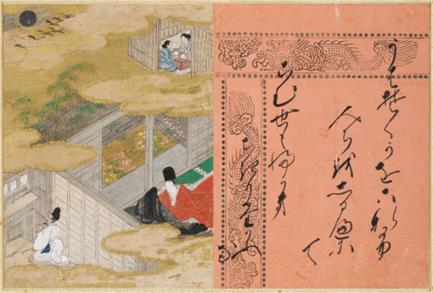

By this means, from the illustration of album to chapter four of the Tale of Genji from Muromachi period, preserved by Harvard Art Museums, we could still gain a glimpse of the sophistication and ingenuity of the aristocratic artifacts of the day. Firstly, the calligraphy on the right side of the figure transcribes poetic and prose excerpts from the Genji narrative, written by calligrapher Jōhōji kōjo, one of the “six prominent Kyoto courtiers from aristocratic lineages of distinguished pedigree” [4]. Since its major audience was the Japanese aristocracy of the time, this poem was written in Heian-period court Japanese, which is highly inflected and has very complex grammar. It says, “Please be guided by the deity of Ubasoku and do not break any sincere promises in the next life, in spite of the unavoidable factors.”

In my perspective, this poem focuses on the unshakable duty of Genji that contribute to the death of Yūgao, who is the female leading character in this chapter, and meanwhile also contains Murasaki's condemnation of Genji's constantly placing lust and personal pursing ahead of qualities such as loyalty and responsibility. Jōhōji kōjo’s wiry and frenetic characters vividly express the heaviness of death and the signing of a short life behind this poem. There is no denying that sometimes he paused so long in some of the characters that left a few ink clumps and black dots on the paper, which would inevitably affect the fluidity of the strokes and the smoothness of the flow between the characters. However, considering the shocking turnings in the plot of this chapter -- the coincidental meeting between two leading characters and the supernatural death of Yūgao just after their affair takes a turn, the expression of Jōhōji kōjo’s proper and well-timed pauses could also be considered as proper, serving the purpose of allowing the readers to appreciate calligraphy not only from an overall perspective but pay more attention to the details, mimicking the mood when they were reading the climax and lows in the plot. Besides, as with most Heian literature, The Tale of Genji was almost entirely written in kana and not in kanji, which significantly improve the smoothness of calligraphy. It is worth noting that all the thoughts and care Jōhōji kōjo puts into his calligraphy is not in vain. On one hand, albums are mainly produced and appreciated by the aristocracy, who are well-educated nobles with aesthetic tastes and often have a unique pursuit of artwork. On the other hand, their insist on art has also contributed to improving the artistic level of the album and comprehend more details of the real aristocratic life in the ancient Japan.

Figure 1: Tale of Genji Album (Genji monogatari gajō) of Illustrations and Calligraphic Excerpts (Two Volumes) [5]

Secondly, the painting on the left side of the figure also enjoys high artistic values. It conveys the season of the chapter in numerous tiny details. The “gold clouds and architectural lines divide the painting into distinct quadrants bearing poetic motifs associated with the auditory landscape of autumn, namely the pounding of cloth and geese” [4]. Additionally, “the garden teems with delicate pink and yellow flowers”, decorating with “Chinese bamboo, dew sparking on the plants, and a cacophony of chirping insects” [4]. Just as the calligrapher Jōhōji kōjo, the painters for the album are also from aristocratic lineages of distinguished pedigree themselves. The perennial upper-class life has cultivated their outstanding aesthetic tastes and superior painting skills to exhibit the illustrations vividly, bringing it closer to the reality through details hidden in the inconspicuous corners in the painting. However, meanwhile, years of solely emphasizing artistic skills without stepping closer to the real life that the mass led could also cause incompatibility of parts of the painting with the reality. For instance, “in keeping with a theme of hidden identity that runs throughout this chapter, Genji is said to disguise his status by wearing a hunting robe, a garment rarely worn of his statue” while in the painting the striking red robe was “embellished with a gold floral pattern, being far from understand” [6]. At the same time however, these unrealistic details stemming from the overly lavish and elaborated skills exactly served as a function to deliver the luxury of the real life in the Japanese court during the Heian period.

What’s more, the painters often adopt the contrast of colors to underscore the details that hint about the vital plots. In the figure, Genji’s robe “falls open casually to reveal the edge of a lightly colored undergarment” and “Yūgao faces Genji, [with] her hair cascading down the back for her robe for the viewers to see” [6]. The contrasting color of Genji’s red robe and eggshell undergarment attracts the audience’s attention to ponder about the sexual relationship between these two characters, as well as the comparison of black hair of Yūgao and her natural snow-white skin highlights the intimation and complicated relationships between them. These ingenious thoughts of painters, like the knots and pause in the Jōhōji kōjo’s calligraphy, serve as a guidance that catch the audience’s eyes when they skim over the painting, implicitly extract the gist of the painting and the breakthrough of which plots it is trying to depict.

4.The details of the Inaka Genji from the Edo period

Nevertheless, the Inaka Genji from the Edo period, written by Ryutei Tanehiko and now preserved by Harvard Library is quite different. During the Edo period, owing to the well-governed rule of Tokugawa shogunate which brought hundreds of years of prosperity and stability to Japan, people in the elaborated economic systems led a self-sufficient life, being divided into four strata -- the samurai, the peasants, the craftsman, and the merchants. The economic development during the Tokugawa period was quite remarkable, including the “urbanization, increased shipping of commodities, a significant expansion of domestic and, initially, foreign commerce, and a diffusion of trade and handicraft industries” [7]. In a word, the Tokugawa government did achieve marvelous national progress and productivity growth in the Edo period. Under these circumstances, the public was able to spare some time to pursue and construct their spiritual world in addition to filling their stomachs and satisfying their basic survival needs. The enlarging access and demands to education allowed literate skills such as reading and painting not to be monopoly to elites anymore. The peasants which took up eighty percents of population also promoted the revolution of the media of traditional books such as album and hand scrolls. They expected a more economic and convenient way for them to extend their knowledge base with the limited budget. Also, the original version of Genji, written by Murasaki Shikibu, composed of large amounts of classical poems which were out of use at that time, still remained challenging and far beyond their ability to read for the mass. In this way, the Inaka Genji, often being considered as an adaptation of The Tale of Genji, but much easier to understand with more simple grammar and sentences gained the popularity among the mass. They were usually made out of cheap and thin paper, comparing with the expensive Chinese paper used for the albums, aiming to minimize the cost of the books as much as possible. Additionally, considering that The Tale of Genji was mostly read by aristocrats in the previous periods, reading the Genji itself was somehow related with the social statues and becoming a representation for the deviation from the lower class. This social impression about the book inevitably prompted the popularity of the copies of Inaka Genji.

In the eye of some scholars, images in the Inaka Genji “should be interpreted expansively to include all manner of replacements -- from pictures to rewritings, from commentaries to poetic allusions, from Genji names to the fifty-two Genji incense signs” since “it was the first mass-market fictional publication to exploit this cyclical relationship.” It was not only a way for the lower and middle classes to learn about Genji, but also a representative of the market economy that products were being made out of the market demands.

Whereas, it is true that “Inaka Genji can never escape being talked about in connection with that classic and thus, by virtue of its own lesser canonical statues, being perceived as secondary, derivative, or even lacking”, but each of its chapter was lavishly produced and packaged. In fact, that the “visual form of Inaka Genji was so elegant that readers unfamiliar with the text of the Genji might well have sensed in it” [8].

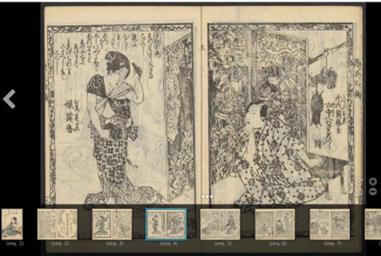

Figure 2: Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudo Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichu-Tenpo 13 [1829-1842] shinchō.[9]

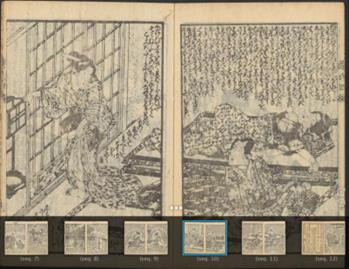

Figure 3: Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudō Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichū-Tenpō 13 [1829-1842] shinchō. [10]

From the figures, we could see that kana is closely connected with each other. In this situation, writings are more functioning as a tool for readers to understand the basic plots and the characters of the Genji, rather than a display of the aesthetic tastes as the album from the previous periods. Due to the cost of the production and the limit budget of the peasants, Inaka Genji is made to pursue a high degree of cost-effectiveness, devoting to clarify the original version of Genji in the limited space of the paper. In this way, most Inaka Genji are homochrome and the illustrations might be viewed as rough or sloppy when the audience closely staring at them. Take Genji’s robe as an example, unlike the delicate details and vivid color that the album adopted to show the class, the painter of Inaka Genji merely used common dots and fine lines to embellish the robe, failing to achieve the same artistic level it initially intended to.

However, it would be unfair to conclude that Inaka Genji is low in artistic merit. The “kuchi-e -- full-page portraits of attractively posed prominent characters that occupy the first page of each chapter -- of both ordinary black ink and thin ink” is an eye-catching innovation that Tanehiko and his collaborators introduced to the publication. “It makes the characters’ clothing appear more solid, add complexity to the textile patterns.” In chapter four, it is also used to “turn the white of the lower half the the page into a billowing fog that enclosed the two characters, separating them from the nebulous gray area behind them and the screen” [8]. This greatly contributes to the impression of lavishness that the work conveys, particularly matching with the aristocratic background that the story of the Genji happened. From this perspective, despite being deprived of the financial and technical support of the Japanese court, the anonymous artisans do fulfill their potential to approximate the original level of artistry and step closer to the background of aristocratic life. To summarize, although sometimes being viewed as a parody of The Tale of Genji, there is no denying that Inaka Genji promoted the familiarity and popularity of the Genji among the public. Facing the situation that its majority audience was lower and middle class instead of elites, it devotes into expressing the whole story in the economic way with minimizing the sacrifice of the artistic value, vaguely associating with the sort of high-class refinement with the Genji.

5.Conclusion

In conclusion, the different audience that the album and Inaka Genji faced leads to the differences between each other. The elites that the album services inevitably pursue the superiority and exquisite arts considering that they seldom confront the constraint on money and time. For the upper class, breaking away from the life that solely busying with basic survival needs, art is a natural way for them to manifest their aesthetic tastes and build up their spiritual world. When Murasaki’s literacy works effectively cleared away the mist of boredom that lingered in their lives, the aristocrats from the Japanese court had no choice but fell in love with the Genji, being intrigued to express their understandings of the stories to the best that they could. Hiring well-known calligraphers and using classy papers were purely different methods for them to show their loving, without any harming to their quality life and vigorous privilege. In this way, it is no wonder that the albums made for the elite always depicted in great care and details, having no necessaries to factor the consumption of time and labor forces. By contrast, the Inaka Genji was made to satisfy the little energy left in the lower and middle classes after engaging in their professions to feed their necessities of life. Chasing art was a luxury for them to nourish their spirits. When albums are imprinted itself upon the history with its high artistic values, the struggling balance that Inaka Genji achieved from the low-cost necessities and efforts for fulfilling aesthetic taste is also quite impressive. Combined these two media’s unique characteristics with the context of the history of the time, they both play an irreplaceable and crucial role in the spread of the Genji in the long history river, creating the foundation of Japanese literary world.

References

[1]. Lyons, Martyn. A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 30. 2011

[2]. Birmingham Museum of Art. Guide to the Collection. Birmingham, AL, p. 49, 2010.

[3]. Sankei News, “Late Kamakura period manuscript of The Tale of Genji found (鎌倉後期の源氏物語写本見つかる)", 10 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

[4]. McCormick, Melissa. "Genji Goes West: The 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Capital", Art Bulletin, College Art Association of America, New York, Mar., 2003.

[5]. Tale of Genji Album (Genji monogatari gajō) of Illustrations and Calligraphic Excerpts (Two Volumes). Accessed 25 November 2023. https://hvrd.art/o/200061

[6]. McCormick, Melissa. “The Tale of Genji: A Visual Companion.” Princeton University Press, pp. 37-39

[7]. Yamamura, Kozo. "Toward a reexamination of the economic history of Tokugawa Japan, 1600–1867." Journal of Economic History, 1973

[8]. Emmerich, Michacl. “The Splendor of Hybridity: Images and Text in Ryutei Tanehiko’s Inaka Genji”, chapter 8.

[9]. Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudo Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichu-Tenpo 13 [1829-1842] shinchō. Harvard University: Harvard College Library, Harvard-Yenching Library. Accessed 25 November 2023. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl:37563804

[10]. Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudō Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichū-Tenpō 13 [1829-1842] shinchō. Harvard University: Harvard College Library Harvard-Yenching Library. Accessed 25 November 2023. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl:37563804

Cite this article

Fang,R. (2024). The Genji Changes: From the Album in the Muromachi Period to the Inaka Genji in the Edo period. Communications in Humanities Research,31,153-159.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lyons, Martyn. A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 30. 2011

[2]. Birmingham Museum of Art. Guide to the Collection. Birmingham, AL, p. 49, 2010.

[3]. Sankei News, “Late Kamakura period manuscript of The Tale of Genji found (鎌倉後期の源氏物語写本見つかる)", 10 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

[4]. McCormick, Melissa. "Genji Goes West: The 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Capital", Art Bulletin, College Art Association of America, New York, Mar., 2003.

[5]. Tale of Genji Album (Genji monogatari gajō) of Illustrations and Calligraphic Excerpts (Two Volumes). Accessed 25 November 2023. https://hvrd.art/o/200061

[6]. McCormick, Melissa. “The Tale of Genji: A Visual Companion.” Princeton University Press, pp. 37-39

[7]. Yamamura, Kozo. "Toward a reexamination of the economic history of Tokugawa Japan, 1600–1867." Journal of Economic History, 1973

[8]. Emmerich, Michacl. “The Splendor of Hybridity: Images and Text in Ryutei Tanehiko’s Inaka Genji”, chapter 8.

[9]. Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudo Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichu-Tenpo 13 [1829-1842] shinchō. Harvard University: Harvard College Library, Harvard-Yenching Library. Accessed 25 November 2023. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl:37563804

[10]. Ryūtei, Tanehiko 1783-1842. Inaka Genji. Edo: Senkakudō Tsuruya Kiemon inkō, Bunsei kichū-Tenpō 13 [1829-1842] shinchō. Harvard University: Harvard College Library Harvard-Yenching Library. Accessed 25 November 2023. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl:37563804