1. Introduction

According to a report by the Vietnamese newspaper "Nhan Dan" on December 26, 2023, based on population and family planning statistics from the Vietnamese Ministry of Health, Vietnam has entered a demographic dividend period since 2006, expected to last until 2042. This period occurs only once and is anticipated to span 30 to 40 years. [1] While there have been some achievements in theoretical and empirical research on the demographic dividend period domestically and internationally, with the continuous evolution of economic growth patterns and population structures, there remains room for further exploration in understanding the future demographic dividend period. Particularly, research on the demographic dividend period in Vietnam is scarce. Therefore, studying the characteristics, challenges, and consequences of Vietnam's demographic dividend period holds significant importance.

2. The basis for the formation of Vietnam’s demographic dividend period

The demographic dividend period, also known as the population dividend period, refers to the span of time during which a country's working-age population, equivalent to or greater than 60% of the total population, predominates. It represents an opportune period for economic development in a country. Studying the formation of Vietnam's demographic dividend period requires attention to its theoretical and empirical foundations.

2.1. Theoretical basis

In the 1990s, the theory of the demographic dividend period gradually gained attention in the field of population-economic relationship studies. This research paradigm broke away from the traditional focus on population size and growth rate in population-economic relationship studies, shifting attention to the demographic age structure characteristics that change with variations in birth and death rates during the demographic transition process. When the working-age population grows rapidly and constitutes a high proportion, this age structure is conducive to economic growth, thereby creating a unique source of growth known as the demographic dividend period.[2]

Scientific research shows that the demographic dividend period usually lasts for 30-40 years, or even 40-50 years. In order to obtain the demographic dividend, a country must undergo demographic transition, shifting from a predominantly rural agricultural economy with high birth and death rates to an urban industrial society characterized by low birth and death rates. In the early stages of this transition, the birth rate decreases, leading to a faster growth rate of the workforce compared to the dependent population. During this period, per capita income also grows rapidly. This economic benefit is the first gain that countries undergoing demographic transition receive.

Starting from 2007, Vietnam officially entered the demographic dividend period as the overall dependency ratio (the population aged 0-14 and 65 and above as a percentage of the population aged 15-64) fell below 50%. Statistical data indicates that Vietnam is currently in a peak demographic structure, with 68% of the population in working age and only 32% requiring support.[3] In the years 2034-2039, the working-age population is projected to peak at around 72 million. Approximately 70% of the population will be in working age, making a crucial contribution to driving GDP growth in Vietnam.[4]

2.2. Current status basis

With the steady development of Vietnam's economy and healthcare sector, the quality of life of the people is gradually improving. As a result, there have been noticeable changes in Vietnam's population distribution, population quality, population structure, gender ratio, and other aspects.

2.2.1. Total population

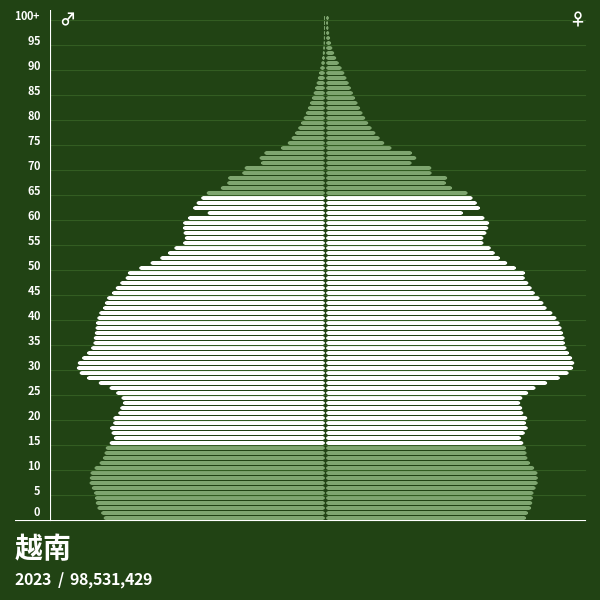

According to the data from the population pyramid, Vietnam's population is approximately 98.5 million people, and it is projected to exceed 100 million by the end of 2023, making it the fifteenth most populous country in the world and the third in Southeast Asia, following Indonesia and the Philippines. The current population structure is conducive to stable economic development, with the country achieving productivity and economic growth over the past few decades.

Figure 1: Vietnam total population chart[5]

2.2.2. working-age population

As of 2021, the working-age population is approximately 67 million people, accounting for 67% of the total population. The gradually aging population structure has prompted the government to adjust the retirement age. In 2022, the government introduced reforms to raise the retirement age for both men and women, with the retirement age for men increasing to 60 years and 6 months, and for women to 55 years and 8 months, aiming to expand the formal working-age population. This segment of the labor force is expected to increase steadily over the coming decades, continuing to support economic growth.

2.2.3. population growth rate

Vietnam's population structure has been supported by a stable population growth rate, maintaining at around 1% annually from 2000 to 2019. However, in recent years, due to the pandemic and continued restrictions on childbirth through the two-child policy, the population growth rate has declined to below 1%, reaching 0.8% in 2021, aligning with the average level of middle-income countries. The decrease in fertility rates is a result of the government's two-child policy. [5]

2.2.4. Aging population

Vietnam is one of the world's fastest aging countries, officially entering an aging society in 2011. With declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy, Vietnam's proportion of elderly individuals is expected to reach 10%-20% by 2035. Vietnam's average life expectancy is around 75 years, higher than the average level in Southeast Asian countries. It is projected that Vietnam's transition from an "aging" society (7%) to an "aged" society (14%) will be completed within 20 years.[6]

2.2.5. Gender ratio

Vietnam exhibits an imbalance in the gender ratio of newborns. In 2000, Vietnam's data indicated a birth ratio of 106 females to 100 males, which escalated to 112 females to 100 males by 2016. The imbalance became more pronounced, with approximately 10% more male births than female births.[6] In 2021, the gender ratio at birth in Vietnam stood at 112 males per 100 females. Based on the current gender ratio, it is projected that by 2025, Vietnam's male population will exceed the female population by four million individuals, primarily comprising the new generation. By 2059, this figure is expected to expand to 2.5 million people, equivalent to 9.5% of the total population.

3. Characteristics of Vietnam’s demographic dividend period

Rapid changes in Vietnam's demographic structure have pushed Vietnam's overall dependency ratio (population aged 0-14 and population aged 65 and above based on the population aged 15-64) below 50%, thus entering a period of demographic dividend. Vietnam’s demographic dividend period has the following characteristics.

3.1. Long duration

The demographic dividend of Vietnam started in 2006 and is expected to end in 2042, lasting approximately 36 years, with a long duration. If Vietnam's demographic dividend period lasts until 2042, it will coincide with the social changes brought about by the century-old changes. The young Vietnamese population will be easier to adapt to new situations and changes, and may be more likely to recognize, develop and apply new things. People will encounter fewer mental and cognitive obstacles, the country will have less resistance to development, and its development will be faster. This will bring unique opportunities for Vietnam's development. Firstly, it will support economic development through human resources. According to the pattern, the demographic dividend period is a unique opportunity for national economic and social development. Vietnam's demographic dividend period is expected to last until 2042, providing ample time for the young population and labor force to experience rapid development, thereby contributing to the advancement of the economy and society.

3.2. Disparate development

Firstly, there is an imbalance in population development across regions in Vietnam. The Red River Delta region has experienced stable growth in the past decade, with a growth rate of 15.70%, attributed to being the political and cultural center of Vietnam. In contrast, the population growth in the northern, central, and coastal central regions has been slower, with a growth rate of only 7.70% from 2011 to 2021, mainly due to limited resources and slower economic development in these areas. Meanwhile, the southeastern region in the south, serving as Vietnam's economic center, witnessed a population growth rate of 23.80% from 2011 to 2021, far exceeding the national average. This is primarily due to the vigorous economic activities and rapid increase in various investment projects in the region.

Secondly, there is an imbalance in the local labor market in Vietnam, with a mismatch between labor supply and demand in different regions, sectors, and types of labor (such as non-skilled workers, managerial workers, and high-skilled workers). Pham Vu Hoang, Deputy Director of the Population and Family Planning Department at the Ministry of Health, stated, "The majority of Vietnamese workers are engaged in low-income, low-protection informal employment (accounting for 54% of informal workers). Workers' professional qualifications remain limited, with only about one-fourth of workers having received training above the primary level.[7]"

3.3. Aging is ahead of modernization

Developed countries enter an aging society when they have essentially achieved modernization, following a pattern of becoming affluent before aging or experiencing simultaneous affluence and aging. In contrast, Vietnam has entered an aging society prematurely, without having fully achieved modernization or economic development, thus exemplifying a case of aging before affluence. When developed countries enter an aging society, their per capita gross domestic product (GDP) generally ranges from five thousand to ten thousand US dollars or more. However, Vietnam's current per capita GDP still places it in the category of moderately low-income countries, indicating relatively weak economic capacity to address population aging.

The aging of the population brings opportunities and challenges to the social economy and requires the country to implement economic reforms. The rapid aging of the population may also lead to future labor shortages and increasing demands for social security among the elderly. As the proportion of the elderly population increases, so does the need for social services to meet the needs of the elderly. Vietnam's social security system is relatively developed, but it is necessary to further strengthen the scope of application of the social security system, family and social assistance programs for the elderly. In addition, it should be recognized that many elderly people have the ability and desire to continue working after retirement age, and the elderly should be given opportunities for economic activity.

4. Challenges faced by Vietnam during its demographic dividend period

The demographic dividend period is a unique opportunity for Vietnam. A prominent feature of the demographic dividend period is the relatively high proportion of the working-age population (15 to 64 years old), currently accounting for approximately 69% of the total population. This is a rare opportunity and a key determinant of whether a country can achieve sustainable development. Resolution No. 21-NQ/TW of the Sixth Plenum of the Twelfth Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam, concerning population work under new circumstances, emphasizes: "Comprehensively address population scale, structure, distribution, and quality issues in interaction with socio-economic development. Strive to maintain fertility levels to achieve a natural balance in birth sex ratios; effectively utilize the demographic dividend period to adapt to population aging; distribute the population reasonably; and improve population quality, contributing to the country's rapid and sustainable development.[8]"The development of Vietnam's demographic dividend period is not without challenges; rather, it faces numerous issues.

Firstly, the quality of the population is not high. In 2021, only 35.4% of Vietnam's population had received tertiary education (completing education beyond secondary school), which is significantly lower than the global average of 42.2%. High-skilled workers in Vietnam constitute only about 11% of the total workforce. The World Bank estimates that if Vietnam's proportion of high-skilled workers remains low and fails to keep pace with the speed of digital transformation, Vietnam could lose approximately 2 million job opportunities by 2045.[9]

Secondly, there is a gender imbalance. In 2006, the male-to-female ratio of births in Vietnam was 108.6 males per 100 females, and by 2021, it had increased to 112 males per 100 females. [10] Among individuals over the age of 45, the proportion of females is indeed higher than that of males. However, due to entrenched patriarchal traditions and the preference for sons over daughters in Vietnamese culture, there is a higher proportion of males compared to females among individuals under the age of 45 in Vietnam.

Thirdly, there is rapid population aging. Due to improving living standards, healthcare, and Vietnam's family planning policies, people's attitudes towards childbirth have changed, leading to a decline in fertility rates and a continuous reduction in the number of working-age individuals. For instance, in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam's economic hub, despite the implementation of a two-child policy, the average fertility rate is only 1.4.

Fourthly, there is inadequate infrastructure development. Compared to other Southeast Asian countries, Vietnam has relatively weak infrastructure, yet holds significant development potential. The increasing urbanization and industrialization in Vietnam are driving demand for electricity, while the current lack of transportation infrastructure struggles to keep pace with rapid economic growth. As the population grows, the need for urban infrastructure becomes increasingly urgent.

Fifthly, there is a lack of environmental protection. In recent years, Vietnam has experienced rapid economic growth and population increase, leading the region in economic growth rate. However, this growth has also brought severe environmental pollution issues. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is one of Vietnam's main air pollutants. For example, in Hanoi in 2019, there were only 8 days where PM2.5 levels were below national standards. Causes of air pollution include vehicle emissions, inadequate urban planning, and dust from commercial and residential construction sites.

Multiple challenges are intertwined to form the dilemma faced by Vietnam during its demographic dividend period. How to deal with the current opportunities and difficulties directly affects the duration of Vietnam's demographic dividend period. In order to alleviate problems arising from the demographic dividend period, Vietnam has been taking measures to implement social security policies and national strategies to improve the quality of social welfare services and cope with the trend of population aging.

5. Conclusion

The demographic dividend period presents both opportunities and challenges for Vietnam's development. In fact, the opportunities of the demographic dividend period do not automatically bring positive impacts but rather must be "won" to "generate" dividend labor force, leading the country towards rapid and sustainable development. If the demographic dividend period coincides with a period of economic stability and if the education system effectively provides knowledge and professional skills to the workforce, it can become a powerful force for enhancing the labor force and promoting economic and social development. Conversely, without appropriate policies, the country may face challenges such as unemployment, falling into the middle-income trap, and an increase in social problems, becoming a burden that hinders long-term development.

References

[1]. Hải Ngô.(2022). Cơ cấu dân số chuyển dịch theo hướng tích cực. Retrieved from https://nhandan.vn/co-cau-dan-so-chuyen-dich-theo-huong-tich-cuc-post731802.html

[2]. David E. Bloom.(2003). The Demographic Dividend. RAND.

[3]. UNFPA.(2011). The Age and Ses Structure of Vietnam’s Population:Evidence From The 2009 Cencus. United Nations Population Fund in Viet Nam, 1-4.

[4]. Judith Banister.(1993). Vietnam Population Dynamics and Prospects. The Regents of the University of California.

[5]. Population-pyramid.(2023).Vietnam population pyramid in 2024 AD. Retrieved from https://population-pyramid.net/zh-tw/pp/%E8%B6%8A%E5%8D%97

[6]. OOSGA.(2023). Overview of Vietnam’s population development. Retrieved from https://zh.oosga.com/demographics/vnm/

[7]. Thiên Lam.(2023). Cơ cấu “dân số vàng” và những thách thức với Việt Nam. Retrieved from https://nhandan-vn.translate.goog/co-cau-dan-so-vang-va-nhung-thach-thuc-voi-viet-nam-post746159.html?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=zh-CN&_x_tr_hl=zh-CN&_x_tr_pto=sc

[8]. Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam.(2021). Văn kiện Đại hội đại biểu toàn quốc lần thứ XIII. Nxb:Chính trị Quốc gia Sự thật, 136, 151.

[9]. Mạnh Bôn.(2023). Tận dụng thời kỳ cơ cấu "dân số vàng" để phát triển. Retrieved from https://www.tinnhanhchungkhoan.vn/tan-dung-thoi-ky-co-cau-dan-so-vang-de-phat-trien-post320702.html?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=zh-CN&_x_tr_hl=zh-CN&_x_tr_pto=sc

[10]. Xu Liping.(2023). What Vietnam has a population of over 100 million means.Retrieved from https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/4C4EJYRBrfK

Cite this article

Liao,R. (2024). Research on Vietnam’s Demographic Dividend Period. Communications in Humanities Research,34,128-133.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hải Ngô.(2022). Cơ cấu dân số chuyển dịch theo hướng tích cực. Retrieved from https://nhandan.vn/co-cau-dan-so-chuyen-dich-theo-huong-tich-cuc-post731802.html

[2]. David E. Bloom.(2003). The Demographic Dividend. RAND.

[3]. UNFPA.(2011). The Age and Ses Structure of Vietnam’s Population:Evidence From The 2009 Cencus. United Nations Population Fund in Viet Nam, 1-4.

[4]. Judith Banister.(1993). Vietnam Population Dynamics and Prospects. The Regents of the University of California.

[5]. Population-pyramid.(2023).Vietnam population pyramid in 2024 AD. Retrieved from https://population-pyramid.net/zh-tw/pp/%E8%B6%8A%E5%8D%97

[6]. OOSGA.(2023). Overview of Vietnam’s population development. Retrieved from https://zh.oosga.com/demographics/vnm/

[7]. Thiên Lam.(2023). Cơ cấu “dân số vàng” và những thách thức với Việt Nam. Retrieved from https://nhandan-vn.translate.goog/co-cau-dan-so-vang-va-nhung-thach-thuc-voi-viet-nam-post746159.html?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=zh-CN&_x_tr_hl=zh-CN&_x_tr_pto=sc

[8]. Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam.(2021). Văn kiện Đại hội đại biểu toàn quốc lần thứ XIII. Nxb:Chính trị Quốc gia Sự thật, 136, 151.

[9]. Mạnh Bôn.(2023). Tận dụng thời kỳ cơ cấu "dân số vàng" để phát triển. Retrieved from https://www.tinnhanhchungkhoan.vn/tan-dung-thoi-ky-co-cau-dan-so-vang-de-phat-trien-post320702.html?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=zh-CN&_x_tr_hl=zh-CN&_x_tr_pto=sc

[10]. Xu Liping.(2023). What Vietnam has a population of over 100 million means.Retrieved from https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/4C4EJYRBrfK