1.Introduction

The urban construction in modern Qingdao, initiated in the late 19th century with urban planning and design, marks one of the earliest significant leaps in the city’s development history. Due to its long-term goals and smooth funding, Qingdao’s construction of its port and city proceeded on a large scale and at a rapid pace. It became a model colony of “Far Eastern modernized colonialism” for German imperialism, achieved through forced occupation and modern urban construction [1].

Camillo Sitte is considered the pioneer of modern urban design. In the late 19th century, he innovated a set of urban design principles that fully embodied German urban characteristics and gained recognition from various Western countries for their artistic and scientific aspects, becoming the mainstream urban design ideology of that time in the West. The German colonial construction in Qingdao coincided with this period, and it naturally adopted the Sitte style in urban design. The German planning system established in Qingdao’s urban form and street space development process was likewise influenced by Sitte’s humanistic and artistic ideas.

This paper aims to explore the importance and scientific nature of humanized urban design guided by Sitte’s urban design philosophy, to find protective strategies in line with Qingdao’s historical context, and to provide guidance for the protection and renewal of Qingdao’s historical districts.

2.Background of the Study

2.1.The Debate Between Technicality and Artistry in Urban Design Theories at Home and Abroad

Since the Industrial Revolution, modern urban construction that emphasizes technicality and economy has emerged, consistently pursuing efficiency, functional rationality, and rapid transportation. This approach has achieved significant accomplishments, such as the efficient use of land, maximizing economic benefits from land, and improving urban public health conditions. However, as with issues in all eras, there has been a strong opposing viewpoint. Urban design theories that prioritize artistry criticize modern urban construction for lacking artistic heritage. They argue it neglects factors such as the characteristics, proportions, and rhythms of urban spaces, the relationship between architecture and urban form, and the impact of urban space on people’s inner psychological experiences. In short, the demands of artistry are inwardly focused, while those of technicality are outwardly focused, presenting a crucial contradiction. This necessitates that in exploring urban design methods today, we should not simply prioritize one aspect over the other. Instead, we should skillfully integrate these two poles in every specific situation, achieving the best overall results through a synthesis of economic and artistic achievements in the given context.

2.2.Destruction of Urban Context in China

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the urban context has suffered unprecedented damage. The adoption of uniform layouts has led to monotonous imagery, with compositions striving for strict rules, symmetry, and grand scales, emphasizing magnificence and heavy political undertones. This approach has ignored the current conditions of cities, as well as historical and geographical particularities, lacking an understanding of the distinctive characteristics of different cities, which has greatly damaged the urban fabric and context. Of course, this is partly related to the adoption of the Soviet urban design model. However, after the 1980s, the rapid economic development and the trend of globalization led to a second wave of urbanization. As people’s material conditions improved, their spiritual needs drove higher demands for urban spaces. Nonetheless, due to various shortcomings in cultural awareness, value orientation, and levels of design and planning, many cities have begun to resemble those abroad. This has led to a disregard for human scale and perception, with blind imitation and an excessive pursuit of grandiosity and Western styles. For a time, constructions of “the largest square of …” were ubiquitous, with European styles sweeping across the country. In reality, China’s urbanization process shares some similarities with the urban situations in Europe during the early Industrial Revolution. Therefore, from an urban design perspective, revisiting Camillo Sitte at this time is particularly relevant and enlightening. It holds significant theoretical and practical value, offering important lessons and warnings [2].

2.3.The Increasingly Prominent Role of Historical Preservation Districts in Urban Design

Historical and cultural districts are vital components of a city, bearing rich historical and cultural resources. Preserving these districts is crucial for maintaining the historical memory of the city, promoting traditional culture, and enhancing the city’s image. Firstly, historical and cultural districts are significant heritage assets that witness the history and culture of a city. Protecting them allows people to better understand and recognize the city’s development process. Secondly, these districts embody the characteristics and styles of traditional culture, serving as important venues for its transmission. Preserving them is essential for promoting traditional culture. Moreover, historical and cultural districts generally retain the most fundamental texture characteristics and basic methods and principles of urban space composition. They provide references and foundations for the design of the city’s own fabric and context. Lastly, these districts can also serve as showcases of the city’s image, attracting tourists and outsiders, boosting the local economy, and achieving social and economic value alongside their artistic significance.

2.4.The Increasing Importance of Humanistic Spirit in Urban Design

In modern cities, despite the convenient living conditions and superior hardware facilities, the absence of humanistic spirit remains an underlying issue [3]. Humanistic spirit lies at the core and essence of urban culture, and the unique charm of urban modernization lies in humanistic care. Currently, urban construction in China tends to prioritize physical objects over people, leading to the fragmentation of urban history and the loss of memory, the homogenization of urban appearances and the vulgarization of images, the alienation of individuals and the marginalization of vulnerable groups, and the neglect of public spaces and the disregard for public needs, among other negative consequences. It is imperative to prioritize people, allowing cities to return to their essential functions. This involves strengthening the promotion and cultivation of humanistic spirit and enhancing cultural consciousness. It also requires paying attention to humanistic care for vulnerable groups, making cities more humane. This can be achieved by expanding public participation among citizens, thus gaining widespread recognition for the humanistic spirit of the city.

3.Sitte’s Urban Design Philosophy: Mother Theme Induction and Artistic Principles

3.1.Motif Induction

3.1.1.Arches and Colonnades

Arches and colonnades, as elements of enclosed spaces, play significant roles in urban design. They serve as a means of segmenting urban public spaces, with colonnades enclosing church squares, each featuring arches for passage. This arrangement achieves its purpose ingeniously. Arches and colonnades share similar spatial significance but differ in functionality and perception at the human behavioral level. Arches primarily facilitate traffic, while colonnades provide shelter for relaxation. Consequently, individuals perceive the transparency of arches and the sheltering aspect of colonnades, leading to different behavioral activities.

Elegant implementations of arches or colonnades can be found in locations such as the Cathedral Square in Salzburg, Austria, the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Italy, and the St. Peter’s Square in Rome. These features elegantly divide the squares without disrupting traffic, creating cohesive spatial enclosures. Additionally, they may serve as frames, allowing people to gaze outwards from arches or colonnades, capturing the surrounding natural scenery.

Figure 1: The Mercenaries’ Loggia in Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy, and the nearby Uffizi Colonnade (source: Baidu Images)

3.1.2.Fountains, Statues, and Ramps

Fountains and statues, as significant themes in urban public spaces, were traditionally never positioned in the center of roads. Instead, they were properly arranged on top of squares, not in the center but along the periphery, akin to an extravagantly decorated central courtyard, exhibiting centuries-old artworks for people to use and admire.

In ancient times, fountains served as functional facilities, typically located beside the main roads accessing the square. The key reason for their placement here was to facilitate drinking water for carts and livestock. Fountains almost never appeared in the geometric center of the square or on any major traffic routes within the square. The rutted tracks left by vehicles in ancient squares naturally divided the square into various-sized open spaces, with fountains positioned in the spaces between the traffic routes. Additionally, in medieval Northern Europe, market fountains were sometimes placed in the dead corners of squares, serving the functional purpose of market squares.

The placement of statues is similar to that of fountains, but with a difference. Statues, as artistic works with content and themes, create a certain atmosphere when placed on squares. This necessitates a reasonable design based on the theme and quantity of statues in relation to the size of the square. Another crucial aspect in determining the placement of sculptures is finding a suitable background. For example, Michelangelo’s David is positioned next to the stone wall on the left side of the entrance to the Old Palace Figure 2. Despite the small and unremarkable square, skeptics initially doubted its suitability. However, when the sculpture was finally placed there, its extraordinary effect was witnessed by all who saw it. In this unconventional location, the large sculpture appeared even more majestic on the relatively constrained square. The uniform dark square stone wall of the old palace provided a background that maximized the sculpture’s silhouette, an effect that cannot be replicated in museums or exhibition rooms, nor envisioned on paper. This is a sensation that can only be perceived when viewed from a human perspective, offering a profound impact.

Another important requirement for fountains and statues as memorials is that they should not obstruct people’s view of the main entrance and the delicate architectural details, affecting their appreciation of the architecture. They should avoid the central axis and be situated to one side. By adhering to all placement rules, avoiding traffic routes, the center of squares, and the central axis, a natural integration of traffic and art requirements is achieved, avoiding traffic routes naturally also means avoiding visual axes, thus achieving a unified artistic perception and demand.

Regarding ramps, this theme emerged after the appearance of perspective theory, aiming to pursue strong perspective effects. People exhaustively employed various perspective tools for architectural backgrounds, moving staircases from indoors to outdoors, creating richly styled ramp themes in front of memorial buildings. Complemented by the three-sided enclosed architectural form, one side of the courtyard is left open to the outside, enhancing the sense of perspective while gradually integrating the courtyard’s scenery into the cityscape.

Figure 2: Michelangelo’s David next to the stone wall on the left side of the entrance to the Old Palace and a fountain in Vienna’s New Market (source: Baidu Images)

3.1.3.Squares and Square Groups

(1) Forms and Scales: The interrelationship between squares and main buildings can be easily categorized into vertical and horizontal types. Square squares are rarely seen, with vertical squares typically featuring the facade of a church as the main facade. The length of the square on one side of the main facade is short, while the length on the adjacent sides is long, creating a longitudinal square facing the main facade. Horizontal squares, on the other hand, usually have the facade of a city hall as the main facade. The length of the square on one side of the main facade is long, while the length on the adjacent sides is short, forming an open square facing the main facade. The combination of square forms in square groups typically involves the interconnection of vertical and horizontal squares, with hardly any instances of adjacent squares in a square group having the same form.

Regarding scale, there is a proportional relationship between the scale of the square and the main building enclosing the square. For vertical squares in front of churches, as shown in Figure 3, the ratio between the height of the church and the length of the square generally ranges from 1:1 to 1:2. For horizontal squares in front of city halls, the ratio between the width of the city hall and the width of the square is typically between 3:1 and 3:1.2. There are also some regularities in the scale of the squares themselves. For example, the main squares in larger cities are larger than those in smaller cities, and among the main squares within a city, each square has the largest scale, sometimes even larger, while all other squares should have the smallest possible scale [4].

(2) Enclosure and Adjacency: The enclosure of squares and square groups is primarily formed through buildings, colonnades, arches, memorials, and even the access of roads. In ancient times, only when the surrounding enclosure was tight enough and the center remained open could it be called a square; otherwise, it could only be considered an open space. With the passage of time, the emergence and maturation of perspective effects during the Renaissance period manifested in urban design as the appearance of stage-like square spaces, where three sides are enclosed by buildings, and the fourth side is open with no road access. This theatrical perspective approach reached maturity during the Baroque period Figure 4. Although the design of one side of the square being directly open to the outside differs significantly from previous principles of square enclosure, its purpose is to shape the palaces and monumental buildings on the square, integrating the magnificent inner courtyard spaces with splendid architecture into the urban landscape for passersby to admire.

Squares are interconnected to form square groups through appropriate adjacency, a common theme in cities, widely distributed throughout European cities. They are laid out based on important church buildings, linking squares of different functional natures to form important gathering places for citizens. Following all the principles mentioned above, layouts and adjacencies are arranged. There are countless ingenious combinations based on differences in terrain, existing buildings, or different squares Figure 5. Through the mutual adjacency of multiple squares, people can move from one square to another, presenting various scenes and effects before them.

Figure 3: Vertical Square: Piazza di Santa Croce in Florence (Self-drawn by the author)

Figure 4: Irregular Square: Piazza del Duomo Nuovo in Florence (Self-drawn by the author)

Figure 5: Square Group Composed of Vertical and Horizontal Squares: Piazza Grande and Piazza Santo Domingo in Modena (Self-drawn by the author)

3.1.4.Road Access Modes

Roads and squares, as the two major components of urban public space, have the windmill-type road access mode considered the most optimal. This mode appeared frequently in ancient squares. Ideally, each corner of the square should only have one road access point, and another direction of the street can only be accessed deep into the street. This design ensures that no second street is visible from the square. Additionally, three to four streets at each corner of the square should enter from different directions, and the roads should intersect the visual axis at a certain angle. They are not parallel to each other. This arrangement ensures that each side of the square appears visually enclosed. From the point of road access, buildings are overlapped through perspective effects, creating a sense of continuity. Through this overlapping effect, people no longer notice unpleasant gaps in the square.

In Italy, the Cathedral Square in Ravenna, the Cathedral of St. Paul in Mantua, and the Piazza della Signoria in Florence all feature classic windmill-shaped road access, as shown in Figure 6. From a human perspective, even if the main streets leading to the squares are wide, the automatic perspective of the human eye still creates a sense of enclosure in the space.

Figure 6: Cathedral Square in Ravenna and Cathedral of St. Paul in Mantua (Self-drawn by the author)

3.1.5.Layout of Buildings

Buildings, as important elements enclosing urban public spaces, generally have embedded or adjacent layouts in relation to significant buildings and squares. Buildings such as churches and town halls are not typically independently situated on the square see Figure 7, but rather, they are adjacent to other buildings on one, two, or three sides. This interconnection is crucial because only when buildings stand independently can they form wide or tall squares. The standalone building facade acts as the main facade dominating the entire square. When looking towards these squares, one can see their individual histories and strong effects. Along with the main entrance and facade, the church itself presents a solemn and powerful effect, while less significant facades or buildings gradually recede from the square.

In Northern Europe, there are some variations where independent church layouts occur see Figure 8. The reason for this can often be traced back to the existence of former cemeteries that once surrounded these churches. After the cemeteries were relocated, the squares covered the area, but the churches remained in their independent state. However, even when the church is independent on the square, it never aligns exactly with the geometric center of the square. The layout still leans towards one side of the square’s interface or towards one corner of the square. In Germany, examples include St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt, St. Martin’s Church in Braunschweig, and St. Stephen’s Church in Konstanz.

Figure 7: Embedded Verona Cathedral and Sant’ Anastasia Cathedral Square (Self-drawn by the author)

Figure 8: Independent Church of San Michele in Lucca and Palermo Cathedral (Self-drawn by the author)

3.2.Artistic Principles

3.2.1.Visual Order and Pedestrian Perspective

Visual continuity and harmony, along with urban space design from the perspective of pedestrians, benefit traffic design for pedestrians and cyclists, and the application of perspective effects, among other factors. These summarize a series of artistic principles and design rules for urban construction. Criticism is directed towards the prevailing formalistic and stereotyped modes, while the organic harmony of medieval urban spatial art is summarized. Advocacy is made for the fundamental principle of coordinating urban space with the natural environment, revealing the inherent artistic composition rules of urban construction.

3.2.2.Humanized Space and Psychological Perception

The advocacy for human-oriented planning methods is discussed from the perspective of perception, showing significant interest in everyday objects, buildings, and cities. It is advocated to base urban design on a rigorous analysis of spatial perception at that time. The artistry of urban design is not geometric or planar but rather based on human feelings and perceptions themselves. After the rise of functionalism, humanized space becomes the theme.

3.2.3.Return to Themes and the Beauty of Harmony

The harmony of a city mainly arises from the mutual coordination among individual buildings. Squares and streets form a unified and continuous space through organic enclosure, constituting the core and soul of medieval European urban construction. “A city should be safe and also bring people pleasure.” Through a pure artistic and technical analysis of historical and recent cities, various themes in their composition are unearthed: they can produce the beauty of harmony and a sensory impact, dispelling people’s sense of dispersion and boredom, and attempting to find a way out to liberate us from the grid system of modern architecture, saving more and more ancient and beautiful cities from destruction.

3.2.4.Adapting to Features and Flexible Plots

Base conditions should not be overlooked, and everything should not be controlled by a unified grid. The goals of rectangular, radial, and triangular systems are only to control the road network, which always serves traffic and not art, because unless on paper, they can never be perceived by the senses, seen by the naked eye. People will lose their direction in an orthogonal system, and the design of intersections and roundabouts will also cause inconvenience for pedestrians. Therefore, based on the original spatial texture of the city, respecting the current terrain, topography, and vegetation, adapting to the natural and human characteristics of the city, curved and zigzag roads are added to the grid street system, enriching the artistic and aesthetic sense of modern cities, reflecting Sitte’s efforts to coordinate the modern and traditional, efficiency and art of the city.

3.2.5.Critical Thinking on Artistic Principles

Sitte’s summary of the artistic principles of urban planning and his pursuit of humanistic spirit and delicate grasp of space have left a profound impact on future generations. He proposed that urban design should follow artistic principles in response to the lack and monotony of modern cities. Although he also dialectically emphasized the important role and achievements of modern urban planning in hygiene and transportation in his writings, due to the emphasis on the artistic nature of cities, he inevitably advocated for medieval-style narrow and winding spaces, weakening the issues of modern urban transportation and hygiene (lighting and ventilation). He did not clearly indicate how to resolve conflicts when artistic principles conflict with modern urban issues such as transportation, hygiene, and population, and simply treated urban space from an “artistic” perspective, which obviously lacks realism and objectivity [5].

4.Manifestation of Humanistic Spirit in Sitte’s Urban Design Concept

4.1.Convenience in Behavior

The essence of humanistic spirit lies in a people-oriented value orientation, manifested in maintaining human existence and dignity, caring for the development of human destiny, and highly cherishing human spiritual and cultural phenomena. In urban artistic design, humanistic spirit is first reflected in meeting people’s various material life needs and providing convenience for their personal life and actions.

4.1.1.Rational Utilization of Themes

By reasonably utilizing and arranging various themes in urban design, people’s lives can be made more convenient in space, ensuring the smoothness and convenience of human behavior. It addresses how to quickly meet pedestrians’ needs for drinking, toilet facilities, rest, cooling off, and avoiding the cold in urban public spaces, as well as how to clearly define pedestrians’ routes of movement in urban public spaces without interference or obstruction, meeting the needs of pedestrians to pass quickly or slowly. These can all be solved through different theme designs.

For example, the use of fountains, placed on one side of the square near the road, allows passing vehicles and animals to drink water; the use of colonnades and arches, while dividing the square space, can provide shade and shelter for pedestrians; and memorials such as statues are never placed on the main traffic flow lines of the square to avoid disrupting pedestrian and vehicular movement. Leaving the center of the square empty, without any buildings or structures in the center, is also to allow pedestrians to reach any part of the square freely, providing convenience for pedestrian activities.

4.1.2.Picturesque Concept and Layout

Through picturesque urban development, which is free, flexible, and unconstrained, not only does it conform to the terrain and landforms of the city itself, but its irregular road network also provides more convenient and smoother traffic than modern regular rectangular grid road networks. Picturesque urban layouts particularly favor “T”-shaped roads, whereas modern road networks are mostly cross-shaped. Considering the needs of vehicles to travel in all directions at intersections, “T”-shaped roads only have 7 non-repetitive meeting situations, among which 3 involve intersecting trajectories, which are unfavorable for traffic conditions. However, at crossroads, there are 54 meeting situations, with 16 involving intersecting trajectories, more than five times the number in “T”-shaped roads. If another road is added at a crossroad, the number of meeting situations for vehicles will increase to 160, ten times more than the previous situation, and the occurrence of traffic interference will increase by more than ten times, severely disrupting traffic flow. At busy crossroads, vehicles even disturb each other’s travel, not to mention the convenience of passage for pedestrians, bicycles, and other non-motorized vehicles.

4.1.3.Design Essence from a Human Perspective

Many public urban spaces in ancient Europe were not based on drawings but achieved excellent effects in reality that cannot be reflected on a flat map. Starting from the convenience of residents’ lives, it provides convenient transportation space, rest space, gathering space, trading space, exhibition space, etc., while also being artistic. From the scale of plaza seating, the height of corridors to the length and width of squares, and the proportion of buildings to squares, the design is based on the scale of the human body and the visual rules, focusing on human activity habits. The emphasis is on the users themselves rather than the city as the object of use.

4.2.Sensory Pleasure

The manifestation of humanistic spirit in urban artistic design not only lies in meeting various material life needs and providing convenience for personal development but also pays full attention to the quality of urban life, meeting the cultural life demands of urban residents, striving to enhance the sense of belonging for urban residents, allowing people to gain sensory pleasure and spiritual enjoyment in urban public spaces.

4.2.1.Reasonable Utilization of Themes

Among the themes, statues are most spiritually inspiring. Different types and quantities of sculptures are placed according to the different attributes and scales of plazas, shaping different plaza atmospheres. For example, in the Olympia Festival Square in ancient Greece, hundreds of sculptures are displayed on a vast plaza, combining to form a grand atmosphere, guiding people to stroll through the square. Similarly, statues like the Athena sculpture on the Acropolis of Athens and the David statue in the Old Palace of Florence dominate entire squares, with their oversized presence complemented by the unified and harmonious architectural backgrounds of the Parthenon and the old palace, causing people to involuntarily stop and admire. Other elements such as harmonious building facades, natural tree arrays, exquisite fountains, and grand outdoor staircases provide people with relaxing, solemn, agile, or serious spiritual experiences, allowing them to immerse themselves.

4.2.2.Picturesque Concept and Layout

Twisting and flexible streets, embedded architectural complexes, and enclosed squares constitute a picturesque urban layout, allowing people to wander through it. What they see are the spires of churches concealed by buildings, wide and free market squares, or solemn and orderly municipal squares, as well as natural entries and elegant exits. In such an environment, buildings become organic entities, enclosing vibrant squares and streets. Through perspective effects, people comfortably and pleasantly enter each different urban public space, never seeing through any corner at a glance, but lingering in it, moving around and changing scenery. Meanwhile, continuous houses satisfy people’s natural inclination to seek lateral shelter, and “T”-shaped roads allow people to move naturally and comfortably in busy streets, reducing the need to cross roads. The aesthetics of the city relax people spiritually, allowing them to start enjoying this world.

4.2.3.Design Essence from a Human Perspective

Many cities are beginning to introduce artistic design concepts, using artistic design techniques to explore urban cultural heritage and spiritual connotations to make up for the deficiencies in humanistic spirit. Multi-sensory, three-dimensional implantation of humanistic spirit. Sensory experience is the direct way for people to receive humanistic spirit. Therefore, urban artistic design adopts a multi-sensory combined mode, implanting humanistic spirit from multiple dimensions such as sound, vision, and touch. Interactive, dynamic implantation of humanistic spirit. Urban landscape art design emphasizes stimulating the interaction between the public and the environment, enhancing the vitality of public art design by guiding audience experience and participation, thereby effectively connecting material landscapes with humanistic spirit.

5.Method Application

5.1.Humanistic Spirit Guided Design of Urban Public Spaces

5.1.1.Humanistic Spirit Guided Design of Urban Plaza Spaces

Opposing deliberate rule-based methods, advocating for the free and flexible construction of plazas, and rejecting rigidity. However, it must adhere to the following rules:

(1) A plaza must first be enclosed, allowing people to have an inward-facing sensation, guiding them to pay attention to the architectural facade design facing the plaza. Therefore, all buildings facing the plaza need to exhibit positivity, with the ground floor facing the plaza relatively open.

(2) The center of the plaza should be left empty, with fountains and sculptures placed at the corners of the plaza. In ancient times, fountains were placed in corners as drinking spots for pedestrians and horses. Nowadays, they serve more as landscape cues marking entrances. Sculptures are generally placed in front of building facades, with background contrast making their radiating space more prominent, reflecting their grandeur and majesty.

(3) The irregularity of plaza space form, using fragmented space to connect roads and plazas, guiding people to transition naturally from the relatively narrow space of the road to the relatively spacious space of the plaza. At the same time, people’s unconscious visual correction function will make the irregular plaza relatively regular.

(4) The scale of plaza groups and plazas: facing horizontal buildings such as city halls, the length-to-width ratio of horizontal plazas should be between 3:1 and 3:1.2, while facing vertical buildings such as churches, the ratio of the length of vertical plazas to the length of buildings should be between 1:1 and 2:1.

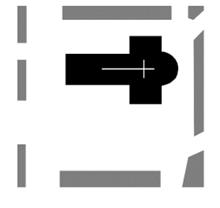

Taking the historical street of Guantao Road in Qingdao as an example, near the Qiyan Clubhouse as shown in Figure 9, there are three plazas around the clubhouse. Currently, there are fragmented spaces at the entrances of all three plazas as transitions, and the center of the plaza is left empty, with trees, parking spaces, and other amenities arranged around the plaza. However, there are connectivity issues between the plazas, and now, due to the military nature of the plazas, they are mostly used for parking and transportation rather than leisure and recreation, resulting in a decrease in plaza usage and an inward-oriented appearance.

It is suggested that within a feasible range, the plazas should be opened to the public, removing rigid enclosure facilities such as fences and walls. Commercial elements should be introduced into the plazas, in line with the museum exhibition function of the Qiyan Clubhouse. Additionally, sculptures, fountains, and other monuments should be incorporated into the plazas as visual focal points, commanding the entire space. The three plazas should be differentiated to give each its own style and characteristics, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9: Application of Plaza Space Design in Guantao Road Historical and Cultural District (Self-drawn by the author)

Figure 10: Ideal Design and Style of Plaza Space (Self-photographed by the author in Macau)

5.1.2.Guided Design of Urban Street Space by Humanistic Spirit

Urban design emphasizes integration with terrain, fully considering climatic characteristics, and respecting natural conditions. At the same time, it should also consider cultural conditions at the time, such as historical periods, era backgrounds, and national characteristics. When shaping the urban spatial form and overall appearance, the planned road network, buildings, railways, etc., should conform to the natural formation of the terrain. The design of urban street space has certain characteristics of the era’s cultural environment.

(1) In dealing with street forms, varied curves and angles are used, based on Camillo Sitte’s advocacy that “the undulations of the ground, original streams, and roads should not be forcibly eliminated” and “the street space that can be seen through at a glance is exactly what the ancients in art tried to avoid.”

(2) The handling of road and environmental scenery enhances the aesthetic appeal of urban space while also showing respect for site terrain and landforms. Monuments are arranged in distant views, serving as the conclusion of broad urban avenues, which is the core of perspective effect.

(3) Starting from the scale and perception of people, the ratio of road width to the relative height of buildings will evoke different psychological perceptions. According to the conclusion of Yoshinobu Ashihara: the larger the D/H ratio (where D represents road width and H represents the height of the building’s outer wall), the easier it is for people to feel distant and scattered in the middle of the road; correspondingly, the feeling of enclosed enclosure weakens or even disappears. According to the different functions of the blocks, they are designed according to different D/H values to evoke different psychological effects in people, affecting their control of and visual effects on surrounding buildings and environments, resulting in different visual artistic effects.

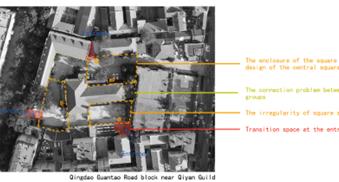

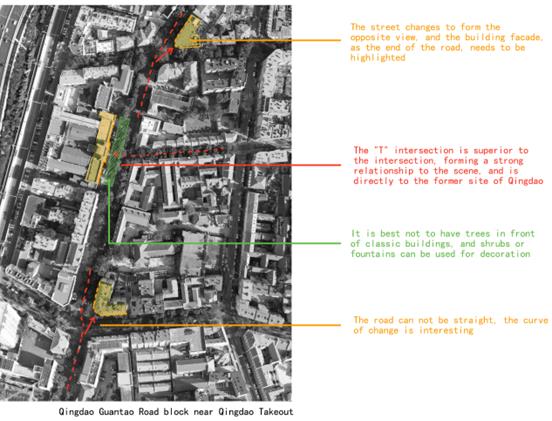

Using Qingdao Guantao Road Historical District as an example, Guantao Road, from Shanghai Road to Guangdong Road, has multiple intersections. Due to its planning based on Qingdao’s hilly terrain, Guantao Road does not form a straight road but instead twists and turns. This results in many street corner vistas that require design. Differential designs are needed based on the different nature of the buildings at the street corners and the varying sizes of the corner spaces.

For example, the intersection of Ningbo Road and Guantao Road is a “T”-shaped intersection, as shown in Figure 11. Directly facing the street is the oldest building in the history of Guantao Road: the Qingdao Exchange. At this intersection, the visual and action flow should be fully displayed without obstruction. Trees in front of the exchange should be removed as much as possible, and the roadway in this area can be slightly elevated to slow down vehicles, facilitating pedestrians crossing Guantao Road from Ningbo Road into the building. Furthermore, although the intersection of Guantao Road with Guangdong Road and Shanghai Road is a crossroads, the roads do not intersect perpendicularly, resulting in angled street corner vistas. Typically, the corners of historical buildings serve as visual focal points. Some are combined with street corner squares to form resting spaces, while others, based on the functional needs of the buildings, serve as the main entrance spaces. The forms vary, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11: Application of street space design in Guantao Road Historical Cultural District (Self-drawn by the author)

Figure 12: Ideal design and style of street space (Self-photographed by the author in Hong Kong, Guangzhou)

5.1.3.Humanistic Guidance Design of Urban Park Green Spaces

The construction of urban park green spaces often occurs at important nodes to improve the surrounding spatial environment or around important buildings in the region to unify stylistic attributes. These park green spaces at key nodes serve as important focal points and are located at population gathering points in the city center, playing a transitional role in space and reflecting the humanistic planning idea of closeness to nature.

(1) Hygienic green spaces should be enclosed within the block, where people are not affected by dust and noise, achieving tangible value objectives: cleanliness, calmness shielded from street noise, and coolness in summer.

(2) Decorative green spaces, street green spaces, and traffic square green spaces serve the sole function of observation, allowing as many people as possible to see them at traffic junctions, involving only psychological effects to enliven the dull traces of artificial construction.

(3) Utilizing the theme of individual trees yields rich spatial effects, achieving picturesque urban design.

(4) The choice between tree rows and shrubbery: symmetrical tree rows are repetitive and monotonous, potentially boring. Considering plant growth, sunlight, and their impact on urban landscapes and traffic, trees can be planted on the sunny side, while tram tracks or parking spaces for bicycles and electric vehicles can be arranged on the shaded side. Tree rows should not obstruct important building facades; instead, decorative water features such as shrubbery or commemorative sprays should be used to provide enough visual space for people to appreciate.

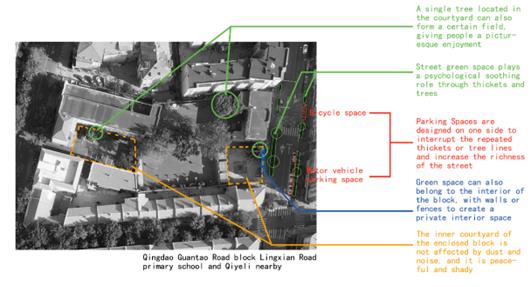

Taking Qingdao Guantao Road Historical District as an example, near Lingxian Road Primary School and the Liyuan Building as shown in Figure 13, many independent small squares are formed within the plots, facing the residents and students inside. At this point, the square tends to be more like a park green space, surrounded by tree rows, distinguishing it from the noisy and chaotic street spaces outside, creating a quiet and shady inward space unaffected by dust and noise.

However, attention should also be paid to the relationship and role of park green spaces with the entire block, as shown in Figure 14, their relationship with historical buildings in the block, the formation of diverse action routes, and their relationship with traffic and parking.

Figure 13: Application of Park Green Space Design in Guantao Road Historical Cultural District

Figure 14: Ideal Design and Style of Park Green Space (Self-photographed by the author in Guangzhou, Macau)

5.2.Humanistic Guidance Design of Urban Architectural Construction

The image of a city mostly resides in the interfaces of its buildings. People’s impressions of a city stem from the visual feedback provided by these architectural interfaces. During walks, most of what people see are the ground-level architectural interfaces and the ground itself. At this moment, the architectural interfaces on both sides of the street become a kind of landscape, eventually settling in the collective consciousness as the city’s image. Several rules need to be followed:

(1) Inheritance and breakthrough of traditional paradigms.

(2) Clear logical construction of order.

(3) Discard the importance of decoration and shadows.

(4) Absolute proportion and relative scale.

(5) Principle of oppositional balance in form.

(6) Basic module units in creation.

These basic rules allow people to feel a unified and harmonious urban style as they shuttle between buildings, as shown in Figure 15. From the style, one can understand the history and context of the city, reflecting the humanistic care of the entire city.

Figure 15: Collage of Architectural Facades in Guantao Road Historical Cultural District (Self-drawn by the author)

6.Strategies Proposal

6.1.Reproducing the Cultural Connotation of Historical Districts to Compensate for the Lack of Urban Humanistic Spirit

A neighborhood is not only a dwelling place for people’s survival and development but also a place for their spirit and soul to dwell. Therefore, design should not only consider external forms but also permeate humanistic spirit and connotations into every corner of the neighborhood through appearances, thereby providing people with good humanistic care and spiritual attention.

Different levels of protection should be provided for the material historical and cultural resources of the neighborhood, while intangible cultural heritage such as collective memory and traditional skills should be inherited. The disappeared areas should be spatially reproduced to enrich the artistic atmosphere and cultural heritage of the neighborhood, thereby enhancing people’s sense of belonging and happiness.

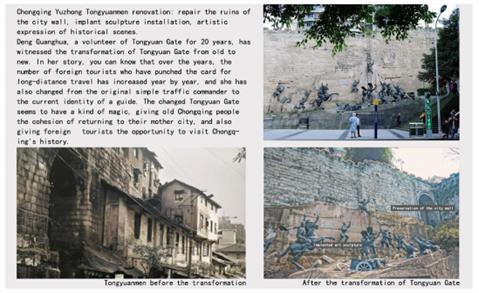

For the Guantao Road historical district in Qingdao, there are many historical memories and collective imprints within the neighborhood. According to its characteristics, different modern translations and reproductions can be carried out. The transformation of Tong Yuan Gate in Chongqing Yuzhong District is a good example, as shown in Figure 16. In the Guantao Road district, the open space in front of the Qiyan Guild Hall once hosted the “May 30th Movement” rally. Place reproduction can be carried out for protection purposes. The Navy Outpatient Clinic at No. 26 Guantao Road used to serve as the emergency room for this area, providing free medical treatment to the people. It is recommended to transform it into a museum to preserve collective memory. The old-fashioned cast iron mailbox at the intersection of Ningbo Road and Guantao Road served as the place where children from nearby schools rang the bell after class. Public space design can be implemented, incorporating forms such as portrait sculptures to preserve scenes. The Liyuan buildings within the neighborhood can be restored and preserved according to the basic layout of courtyard buildings, but attention should be paid to adaptation to functionality during preservation. While ensuring the functionality first under the unchanged overall pattern, form preservation should follow. For the original characteristic old roads within the neighborhood, signage should be designed, including three-dimensional or planar signs, reflecting previous names and historical events.

Figure 16: Case Study of Cultural Protection in Guantao Road District: Transformation of Tong Yuan Gate in Chongqing Yuzhong District

6.2.Considering the Urban Scale of Historical Districts to Reflect the Core Concept of People-Oriented

While renewing and constructing neighborhoods, newly added buildings, neighborhood roads, and neighborhood layouts should all continue the historical style of the neighborhood, ensuring the overall cultural temperament of the neighborhood remains consistent, unified, and harmonious. At the same time, bottom-level designs should consider pedestrian scale. Whether it’s the ratio of width to height of road buildings, the width of sidewalks, barrier-free design, or the scale of square steps, they all demonstrate the core idea of people-oriented design.

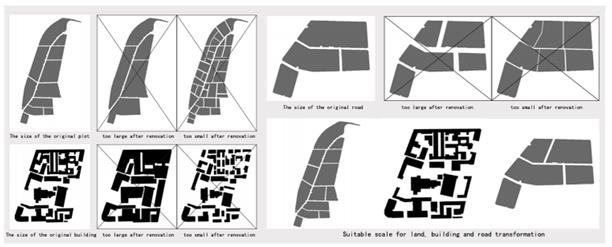

For the Guantao Road historical district in Qingdao, strict control should be exercised over the scale of streets, plots, and buildings within the neighborhood, as shown in Figure 17. The width of the streets should range between 6 to 10 meters, plot sizes should range from 46×75 square meters to 89×263 square meters, and building sizes should range from 152 square meters to 4780 square meters. Preserving the neighborhood’s original three vertical and five horizontal road grid pattern is important. Additional lanes can be constructed, but changes in plot size should remain within a reasonable range according to the previous requirement. The proportion of road width to plot width within the neighborhood should be controlled between 0.03 and 0.1, while the size ratio between plots should be controlled between 0.3 and 1.

Figure 17: Schematic Diagram of Scale Division in Guantao Road District (Self-drawn by the author)

6.3.Enhancing Public Participation in Historical Districts through Sustainable Development with the Aid of Artistic Design

Artistic design in neighborhoods should fully embody humanistic connotations. It not only requires the design unit and the development blueprint designated by the administration but also necessitates the participation of urban residents. The thoughts and opinions formed by urban residents over long periods of life are important references for artistic design. By considering this content, it helps to obtain more recognition from residents for neighborhood artistic design, thereby achieving a “consensus” design, truly allowing more people to share in artistic design, and ultimately promoting the sustainable development of humanistic spirit in urban artistic design [6].

For the Guantao Road historical district in Qingdao, a comprehensive investigation of public opinion was conducted to assess the value of roads within the district. Guantao Road, Ningbo Road, and Tangyi Road have high historical value, Lingxian Road and Wusong Road have high artistic value, and Shanghai Road and Market First Road have high scientific value. Dong’a Road, Zhaoyuan Road, and Guangdong Road have high cultural and social value. Accordingly, different levels of protection were implemented for the architectural, road, and landscape material resources, based on conservation regulations issued by cultural heritage units or housing and construction bureaus.

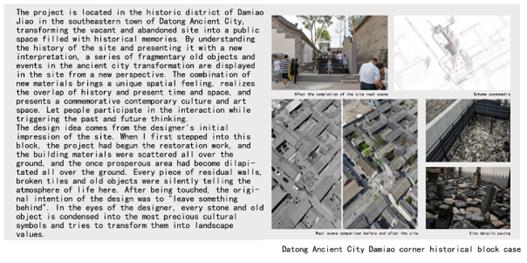

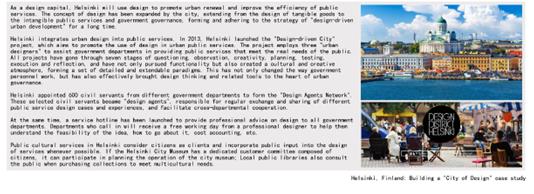

Simultaneously, collective memories of residents within the neighborhood, such as buying monthly tickets, the barrel-shaped building photography exhibition, and the centennial old plane tree ceremony, were reshaped and reproduced. Non-material resources such as the financial and commercial cultural atmosphere in the neighborhood, the construction techniques of the Yuanji Li Qingdao courtyard, and the characteristic stories of the Guantao Road bus terminal were reconstructed and protected. Design and reconstruction of physical spaces were used to preserve people’s memories of non-material resources. Museums and other large public buildings were designed for exhibition and preservation, and memories were retained through ordinary public spaces in the streets and alleys. During the design phase, a large number of online questionnaires were distributed to attract public participation for evaluation, facilitating timely feedback on opinions and modifications and improvements to the plan. Ultimately, the aim is to present a plan with high levels of public satisfaction and participation, drawing inspiration from examples such as the Daming Temple in Datong Ancient City and Helsinki in Finland, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18: Examples of Public Participation in Urban Artistic Design

7.Conclusion and Implications

As long as people’s pursuit of urban art remains eternal, the Sitte urban design principles will have enduring vitality, and cities embodying Sitte’s urban design concepts will continue to be appreciated and loved by people. Even today, in the 21st century, the idea of balancing artistic principles in urban design still influences the urban development and construction of Qingdao. For today’s urban managers and designers, the protection and renewal of Qingdao’s historical and cultural districts must be approached with an artistic perspective and cultural insight, placing them carefully in the long river of human cultural development. Drawing lessons from history and excavating the future path of urban landscape construction from German-style planning, viewing urban space with an “artistic” perspective, and returning to the perspective of space and culture to systematically analyze the design concepts of the city, all become new ideas for contemporary Qingdao to enhance the quality of urban design.

References

[1]. Jiang, Z., & Wang, B. (2011). Sitte’s urban design concepts in the street morphology of Qingdao during the German occupation period. Huazhong Architecture, 29(8).

[2]. Wang, P., Wang, W., & Huang, G. (2006). The origin of humanized urban design: Discussing the significance of Camillo Sitte’s principles in China’s square construction. Foreign Building Materials Technology, (6).

[3]. Wang, R. (2021). On the compensation of urban humanistic spirit by artistic design: A review of “Urban Design Following Art Principles”. Modern Urban Research, (12).

[4]. Sitte, C. (2020). Urban Design Following Art Principles. Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press.

[5]. Cai, Y. (2002). “Urban Design Following Art Principles” - The influence of Camillo Sitte on urban design. World Architecture, (3).

[6]. Chang, M., & Wu, M. (2022). Innovation and integration of humanistic spirit in urban art design: A review of “Urban Design Following Art Principles”. Modern Urban Research, (5).

Cite this article

Li,M. (2024). The Guiding Role of Humanistic Spirit in Sitte’s Urban Design Philosophy in Protecting Historical Districts — A Case Study of Qingdao Guantao Road Historical and Cultural District. Communications in Humanities Research,38,7-25.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Jiang, Z., & Wang, B. (2011). Sitte’s urban design concepts in the street morphology of Qingdao during the German occupation period. Huazhong Architecture, 29(8).

[2]. Wang, P., Wang, W., & Huang, G. (2006). The origin of humanized urban design: Discussing the significance of Camillo Sitte’s principles in China’s square construction. Foreign Building Materials Technology, (6).

[3]. Wang, R. (2021). On the compensation of urban humanistic spirit by artistic design: A review of “Urban Design Following Art Principles”. Modern Urban Research, (12).

[4]. Sitte, C. (2020). Urban Design Following Art Principles. Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press.

[5]. Cai, Y. (2002). “Urban Design Following Art Principles” - The influence of Camillo Sitte on urban design. World Architecture, (3).

[6]. Chang, M., & Wu, M. (2022). Innovation and integration of humanistic spirit in urban art design: A review of “Urban Design Following Art Principles”. Modern Urban Research, (5).