1.Introduction

1.1.Research Background and Questions

The British Museum, established in 1753, is the largest and most famous museum in the UK, focusing on the preservation and documentation of classical artifacts [1]. Nevertheless, controversy over the ownership of its collection, especially those originating from colonial era conquests, has always existed [2]. As a repository of a vast array of cultural heritage, the British Museum has become a frequent target of criticism in such discussions [3]. Among its collections, there are approximately 23,000 Chinese cultural relics, including bronzeware, paintings, and jade items, showcasing China's rich cultural heritage [4]. When these Chinese artifacts are placed within the context of the British Museum, they inevitably face a cultural identity dislocation. Against this backdrop, what measures has the British Museum taken to reconstruct the cultural identity of these Chinese artifacts? This undoubtedly merits further exploration.

1.2.Object of Study

This paper selects the "China and South Asia" page on the official website of the British Museum as its object of study. With the rapid development of the internet, museums around the world have established their own official online platforms to enhance their public outreach efforts [5]. In conducting an in-depth analysis of the content on the British Museum's official website, this research adopts the method of multimodal discourse analysis. This analytical approach involves both textual and visual dimensions, aiming to explore how the British Museum's official webpage presents Chinese artifacts from the perspectives of formal and cultural context levels within the multimodal discourse analysis framework [6]. Through the constructivist viewpoint within identity theory, this paper further elucidates how the website constructs new identity recognition for these Chinese artifacts through its display strategies. Notably, this study's analysis and discussion will simultaneously focus on both the artifacts themselves and the museum. This dual-pronged research method is due to the close interrelationship between the artifacts and their exhibiting venue—that is, the museum [7]. A comprehensive examination of these two aspects allows for a deeper understanding of how the British Museum utilizes its website platform not only to showcase but also to reconstruct the cultural identity of Chinese artifacts.

2.Theoretical framework

2.1.Multimodal Discourse Analysis Theory

The development of digital technology has transformed human communication modes from primarily relying on a single language to encompassing a variety of complex media including language, images, and sounds [8]. Therefore, traditional text analysis alone is no longer sufficient to fully understand social behavior and its underlying meanings. Since the 1990s, multimodal discourse has become a key area of study in social semiotics. Based on Halliday's systemic functional grammar theory, scholars have further explored multiple dimensions of multimodal grammar, including visual grammar, color grammar, and musical grammar [9]. These studies not only inherit Halliday's foundational systemic functional grammar but also extend traditional grammar analysis to non-textual symbols. For instance, research on visual grammar reveals the role of images and visual elements in information transmission and meaning generation [10], color grammar discusses the role of color in communication, and musical grammar examines the connection between musical structure and semiotics [9]. Multimodal discourse, as a mode of communication, involves auditory, visual, and tactile senses and achieves communication through various symbolic resources such as language, images, sounds, and actions [11]. This multidimensional communication mode emphasizes that besides text, other elements like visuals and sounds can also convey complex and rich information.

In current academic discussions on multimodal discourse analysis, systemic functional linguistics is widely regarded as a very suitable theoretical model [8]. The core view of systemic functional linguistics is that language is a multifunctional system, whose functions are realized in different social and cultural contexts [12]. For multimodal discourse, systemic functional linguistics provides a powerful tool for analyzing and interpreting different symbolic systems, including language, images, and sounds. This analytical method focuses not only on the internal structure of a single modality but also emphasizes the interaction and integration between different modalities [8]. Its theoretical framework does not need any fundamental changes to accommodate new analytical purposes. Although the scope of multimodal discourse analysis continues to expand, systemic functional linguistics theory remains directly applicable without modification. Martin summarized this framework as consisting of five system levels: cultural, contextual, meaning, formal, and media levels. This paper mainly focuses on the cultural, contextual, and formal levels.

The cultural level is key to multimodal communication, determining traditions, forms, and technologies of communication. Without the cultural level, situational context cannot be explained [13]. This level includes people's thought patterns, philosophy of life, living habits, and societal norms that constitute ideology, as well as the communicative procedures or structural potentials that realize this ideology, known as genres [6]. In specific contexts, communication is constrained by contextual factors determined by discourse range, discourse tone, and discourse mode. Meanwhile, this process must also realize the chosen genre in a certain communicative mode. At the discourse meaning level, there are conceptual meanings, interpersonal meanings, and compositional meanings constrained by discourse range, discourse tone, and discourse mode [6].

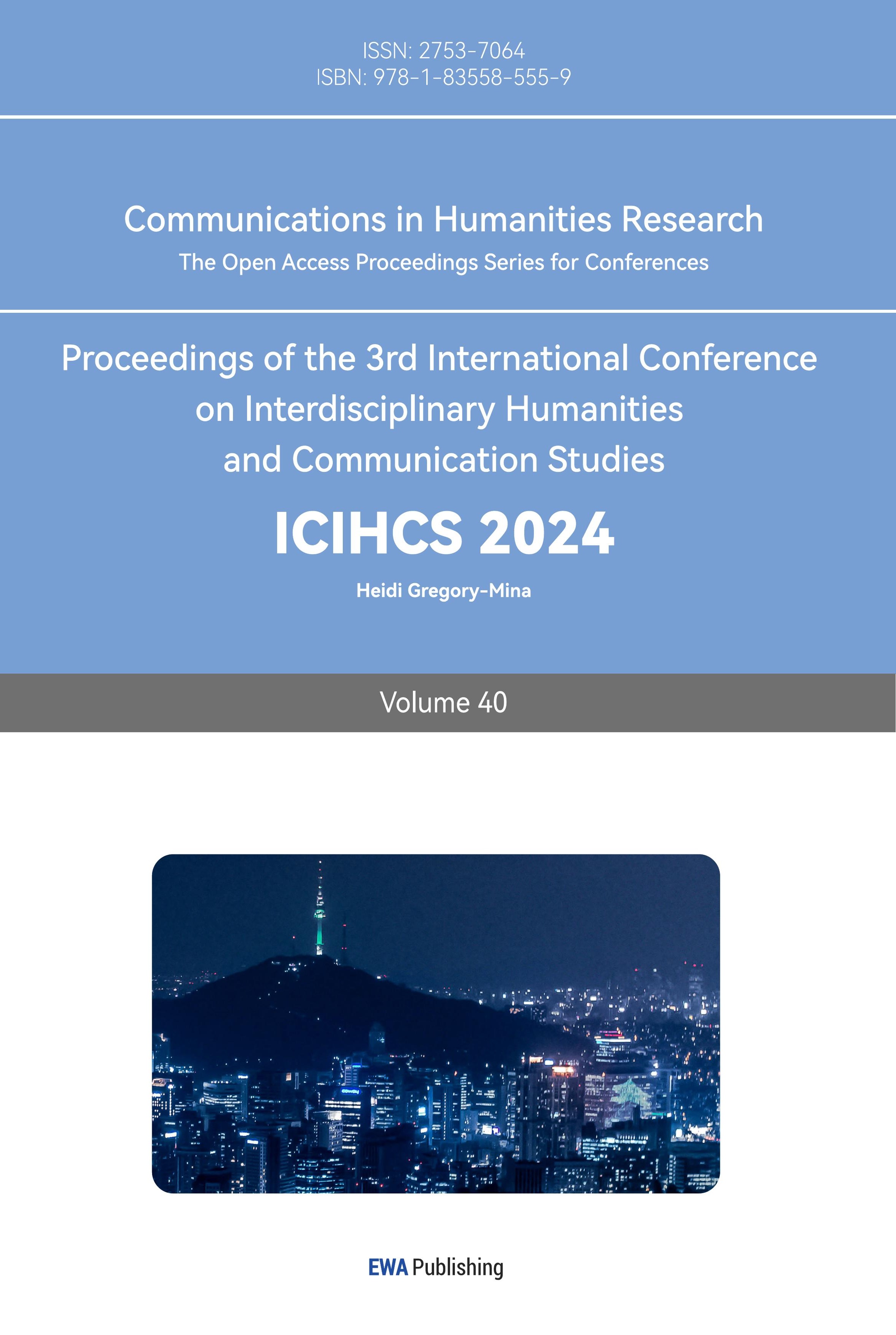

Within the vocabulary and grammar system of language, elements that carry presupposed meanings can be distinguished, along with the rules for combining them into more complex structures.[14]. Within the academic field, these are defined as vocabulary and grammar [14]. This concept is not limited to linguistics but applies equally to other media such as visual, audio, and tactile. Each medium possesses its unique basic elements and combination rules. From a formal perspective, the analysis focuses on exploring the specific roles of vocabulary and grammar in different media. Moreover, the multimodal discourse analysis framework further pays attention to the interactive relationships between different forms and their combined effects [15]. Zhang Delu categorizes multimodal discourse forms into four types: linguistic, visual, auditory, and tactile. Based on the principle of "whether one modal discourse needs another modal to fully express its meaning," he divides the relationships between multimodal discourse forms into complementary and non-complementary relationships. In complementary relationships, he further subdivides them into reinforcing and non-reinforcing relationships based on whether there is a dominant modality among multiple modalities and whether all communicative modalities are essential. In non-complementary relationships, he subdivides them into overlapping, inclusive, and contextual interaction relationships based on the interrelationships among multiple modalities (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Multimodal Discourse Forms and Relationships by Zhang Delu [6]

2.2.Identity Theory

Academic discussions on identity mainly focus on two theoretical frameworks: essentialism and constructivism [6]. The essentialist view posits that the formation of identity stems from a common origin, structure, or continuous shared experiences within a specific period, containing inherent, fundamental, and unchanging components [16]. In contrast, constructivism emphasizes that identity is constructed through diverse contexts via intersecting and even opposing discourse practices, always in a state of dynamic change. The focus of knowledge exploration has shifted from "What is the nature of knowledge?" in essentialism to "How is knowledge produced?" in constructivism [17].

By the end of the 20th century, Alexander Wendt established social constructivism as the mainstream theory in the field of international relations with his work "Social Theory of International Politics" [18]. Over the past twenty years, constructivist theory has achieved significant development. Its core concepts—the importance of identity and norms in international relations—have been widely recognized by other theoretical schools [19]. An increasing number of scholars from sociology, social psychology, psychology, communication studies, linguistics, and other fields have adopted the perspective of social constructivism to study how identity is dynamically constructed, negotiated, managed, and communicated in discourse [20]. They have proposed a series of new views on identity and methodologies for analyzing its construction, arguing that identity is not fixed, predetermined, or unidirectional but is dynamically, actively, and online constructed through communication processes [20]. This perspective fundamentally challenges the traditional essentialist view of identity.

This paper explores the issue of identity recognition of Chinese cultural relics on the official website of the British Museum, primarily based on the theory of identity construction proposed by Stuart Hall in 1996 [21]. This theory includes several core points:

1. Identity is not a fixed attribute but an interactive dynamic process. The Foucaultian school argues that an individual's self-identity is "reconciled" into social relations through interaction with external forces and knowledge. Identity is not inherent but gradually formed under the influence of social relations [22]. The formation of identity occurs in specific interactive contexts, depending on concrete situations and contexts [23]. An individual's identity does not exist in isolation but is continuously constructed and reshaped through interactions with others and the social environment.

2. The realization of identity requires discourse [24]. This means that individuals present their identities through language and other forms of expression, which are profoundly influenced by sociocultural backgrounds and power relations.

3.Literature Review

3.1.Current Research Status on Multimodal Discourse Analysis at Home and Abroad

International research on multimodal discourse analysis mainly focuses on theoretical constructions based on M.A.K. Halliday's systemic functional linguistics, such as the studies by O'Toole [25] and Kress [19], which are influenced by Halliday's socio-semiotic theory. Their analysis of multimodal discourse is based on social semiotic analysis grounded in Halliday's functional linguistics; Norris [8] further developed interactional discourse analysis theory based on Scollon's viewpoints [26]. According to Scollon, interactional discourse analysis theory is based on interactional sociolinguistics [26]. Norris [8] further proposed that social interaction is inherently multimodal and emphasized that different modes of communication participate in interactions to varying degrees in specific environments, introducing a new analytical method. Additionally, applications of multimodal discourse analysis are popular. For instance, Emilia Djonov and Zhao Sumin explored discursive expressions in popular culture through multimodal critical analysis [27]; while Linda C.S. Wong focused on multimodal discourse analysis of politics and protest activities in the context of digital pop culture [28]. However, research on exploring digital websites through multimodal discourse analysis remains relatively limited, mainly concentrating on website marketing strategy analysis. For example, Katherine Wihsah's study focused on the multimodal analysis of the "girl effect" on sports websites [29], while Vana Koulach and Daniel Laresh-Orbach discussed multimodal symbols as key factors for brand websites to attract online traffic [30].

Domestic research on multimodal discourse analysis mainly concentrates on building theoretical frameworks of multimodal analysis, official image shaping, and English teaching methods. For example, Zhang Delu, Xin Zhiying, and Dai Shulan summarized the comprehensive theoretical framework [31], origins and progress, different schools and current development status [32] of multimodal discourse analysis; Liu Yu and Zhang Hongjun used multimodal discourse analysis to analyze how political documentaries shape national images [33], Huang Dongqun explored the construction of Fujian's image through multimodal discourse analysis [34]; scholars like Zhang Delu [35], Wang Lu [35], and Zhu Yongsheng [36] integrated multimodal discourse analysis thinking into foreign language teaching. Research on using multimodal discourse to analyze digital websites is relatively limited, mainly focusing on Sino-foreign comparisons and official image shaping. For example, Chang Yiyuan applied multimodal comparative analysis to museum websites in China and the USA [37], Zhao Ying and Zhang Xiaohui analyzed economic promotional language on Pudong and Binhai Development Zone websites from a multimodal representation perspective [38].

3.2.Current Research Status on Identity Analysis at Home and Abroad

When analyzing domestic and international research on identity, it can be observed that scholars mainly focus on network identity and national ethnic identity. For example, Pan Shuya and Zhang Yuqi deeply analyzed identity issues exhibited in virtual network fan community interactions [39], Triandafyllidou's work focused on the relationship between national identity and the Other [40], He Jinrui and Yan Jiryong expanded research from mere ethnic identity to national identity [41], Slater's study emphasized the impact of online and offline social relations on identity [42], Triandafyllidou's research proposed the relationship between national identity and the Other [40].

3.3.Current Research Status on Museums and Multimodality, and Museums and Identity Recognition

In the field of museum multimodal analysis and identity recognition, the international academic community mainly focuses on the presentation of specific exhibition themes and the division of museum functions. For example, Miles E. Hollokav explored the use and potential of virtual space on British and American museum websites [5]; Falk discussed effective methods of museum learning from the perspective of identity recognition [43]. In contrast, domestic research focuses more on optimizing the external manifestation of museums and the protection and inheritance of cultural heritage. For example, Liu Meijun and Yu Xiao proposed suggestions for enhancing museum interactive experiences based on multimodal analysis [44]; Laurajane Smith and Zhang Yu focused on critical research on intangible cultural heritage in museums [45].

These research results indicate that there is still relatively little research on confirming the analysis related to cultural relics and museum identity recognition through multimodal discourse analysis. Therefore, this study is necessary and pioneering in exploring this field.

4.Analysis and Discussion

4.1.Multimodal Discourse Analysis of the British Museum's Website on Chinese Artifacts Cognitive Construction

When analyzing how the British Museum official website utilizes text and images to shape visitors' basic understanding of China and South Asia, the focus is primarily on two core aspects. Firstly, how specific semiotic symbols imbued with meaning are used to construct cognition; secondly, through combining different semiotic symbols and assigning a certain meaning to this combination, thereby utilizing the function of syntax[6]. Additionally, this study also emphasizes the analysis of the interrelatedness between different media forms, particularly how text and images on the website interact to collectively shape visitors' basic understanding and construct identity recognition of Chinese cultural artifacts.

Initially, the official website aids visitors in establishing a preliminary understanding of Chinese cultural artifacts by showcasing specific items such as Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain and Tang dynasty tomb figures. According to Halliday's systemic functional grammar theory, language is considered a social symbol system with conceptual, interpersonal, and textual functions. In this context, items like blue-and-white porcelain have been encoded as "cultural symbols" of China throughout history[46]. The dissemination of these symbols helps recipients grasp the ethnic cultural significance behind them[47]. Therefore, when visitors encounter these terms on the website, they can rely on their familiarity with these symbols to establish a connection with the exhibition area without introducing new concepts[47]. By reinforcing visitors' existing social cognition, they are encouraged to construct an imaginative image of Chinese historical culture.

On the official website, displayed images include but are not limited to a set of Tang dynasty tomb figures and a Cloisonne covered jar depicting a dragon from the Ming dynasty. The relationship between these images and textual descriptions forms a coordinated relationship within a non-complementary relationship[6]. In this relationship, the two media forms do not substitute for each other but work together to enhance the effectiveness of information transmission[14]. The non-complementary relationship emphasizes the indispensability of both media forms as complements to each other. For example, in the case of the British Museum's official website, if images were lacking, textual descriptions alone would not fully convey the exhibition's theme since visitors often need specific visual information to aid their understanding. Conversely, without textual explanations, visitors unfamiliar with the cultural background of the items may feel confused. Therefore, the complementarity of text and images lies in their ability to collaborate, assisting visitors in constructing a holistic understanding of specific historical cultures in the exhibition area through cross-modal means[8].

Furthermore, based on the foundational cognitive constructions of China and South Asia, the official website strategically combines specific semiotic symbols to create a parallel relationship between visitors' cognition of China and South Asia. This process not only facilitates a profound understanding of each but also contributes to forming a holistic understanding of Asia and the Orient[48]. For instance, in the initial introduction on the website, it mentions that half of the gallery showcases Chinese art and material culture from 5000 BC to the present, while the other half displays the history of South Asia from early human occupation to the present by chronological order and region. Consequently, visitors begin to map their impression of Asia from these two perspectives, avoiding fragmented understanding and instead forming a holistic cognition of Asia and even the Orient. Illustrations ranging from the Sitar of India, exquisite Tara Goddess statue of Sri Lanka to the aforementioned Ming dynasty Cloisonne ware not only serve the cultural image construction of China and South Asia through a coordinated relationship in a non-complementary manner but also form a complementary relationship through combining media to serve the holistic image construction of Asian culture and even the Orient[6]. However, simultaneously, this weakens the identity recognition of Chinese cultural artifacts.

Whether through directly assigning meaning to semiotic symbols or through combining to reinforce the overall impression, the British Museum's official website cleverly employs text and images to intentionally guide visitors beyond the discourse space into a specific spatial area, blurring the origins of Chinese cultural artifacts' identity and thereby reconstructing the basic identity cognition of that region.

4.2.Multimodal Discourse Analysis of the British Museum's Website Self-Cognitive Construction

This paper adopts the cultural and contextual levels of multimodal discourse analysis to analyze how the British Museum's official website uses text and images to construct visitors’ reasonable cognition of Chinese artifacts in the museum. At the cultural level, the key to realizing multimodal communication lies in being influenced by ideology and genre [8]. At the contextual level, the communication process is situated in a specific situational context, where communicators make choices about meaning, thus forming the generation process of discourse [6].

The cultural context presented on the British Museum's official website reflects the changing self-definition of global museums [49]. The specific situational contextualization process refers to visitors gradually developing cognition and identification with Chinese artifacts and their underlying culture through browsing the website [50]. For instance, upon visiting the "China and South Asia" section of the official website, the first image presented (as shown in Figure 2) depicts an adult woman pointing at a glass display case in an exhibition scene, speaking to a young girl beside her. Based on this scene, it can be reasonably inferred that the woman might be a mother visiting the museum with her daughter and explaining to help her understand the exhibition content. From the audience’s perspective, when accessing an online platform introducing foreign cultures, immediate contact with information about the museum's educational role effectively enhances public awareness of the museum's educational function [51]. Similarly, in showcasing Chinese artifacts, introducing viewpoints from international critics (non-Chinese) introduces a cross-cultural symbol system, tapping into the potential of universal symbolic meaning, thereby guiding audiences towards a standardized interpretation of symbolic meaning [50]. Moreover, the official website cleverly interconnects these symbols, thus constructing a complex multimodal discourse symbol structure [8]. In this structure, symbols are manifested through different media, and the official website utilizes text and images to enhance the potential meaning of these symbols, thereby generating a phenomenon of multimedia interaction [52].

Figure 2: Screenshot of the official website of The British Museum

To further analyze how the official website of The British Museum constructs visitors' reasonable cognition of Chinese artifacts in the museum, macro-proposition analysis from discourse analysis can be used to elucidate. Taking the top jump link, "Exploring the Silk Roads," as the specific object of analysis:

Theme: Exploring the Silk Roads

Macro-proposition M1: Introduction to the Silk Roads

Proposition P1.1: Definition of the Silk Roads

Proposition P1.2: The connection between the Silk Roads and the world

Proposition P1.3: The situation in China at the time

Macro-proposition M2: How the world discovered the Silk Roads

Proposition P2.1: Multinational archaeological expedition teams went to explore northwest China

Proposition P2.2: Introduction to one of the representative figures, the Budapest archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein

Proposition P2.3: An overview of Stein's collection

Macro-proposition M3: Representative artifacts of the Silk Roads

Proposition P3.1: The Dunhuang manuscript cave discovered by Stein

Proposition P3.2: Other artifacts discovered by Stein

Macro-proposition M4: The British Museum's exhibition of Silk Road artifacts

Proposition P4.1: Display of Stein's collection

Proposition P4.2: Bequest of Stein's collection

The text content of the "Exploring the Silk Roads" special page is divided into three categories: Macro-proposition M1: Introduction to the Silk Roads, Macro-proposition M2: How the world discovered the Silk Roads, Macro-proposition M3: Representative artifacts of the Silk Roads, and Macro-proposition M4: The British Museum's exhibition of Silk Road artifacts involves handling these macro-propositions through three main macro-rules: Deletion, Generalization, and Construction [53]. Through these rules, key information is extracted from the text to arrive at the theme. The four macro-propositions of the special page delete the historical origins and cultural connotations of the Silk Road artifacts in China, instead generally emphasizing the connection between the Silk Roads and the world, thereby constructing a direct link between Chinese artifacts and the Western world, indirectly establishing a direct link between the artifacts and The British Museum.

4.3.Analysis of the construction of identity for Chinese artifacts on the official website of The British Museum

Consistent with the approach of multimodal analysis, the construction of identity can also be developed from two aspects: one is how Chinese artifacts themselves construct identity through the official website, and the other is how The British Museum constructs the identity of the artifacts through its official website.

From the perspective of constructivism of identity, identity is interwoven and constructed among intersecting and even opposing discourses in different contexts, while also being shaped and continuously influenced by social environments [54]. Unlike "essentialism," which views identity as relatively fixed natural characteristics of people or societies, constructivism considers identity not as fixed traits nor as static products, but as an ongoing process [55]. When Chinese artifacts become part of an exhibition at The British Museum, their original identity gradually fades with transnational exhibition, while an identity associated with The British Museum is reinforced. For example, taking the Ming Dynasty Jingtai period blue-and-white dragon pattern jar as an example, as a relic from the Xuande period of the Ming Dynasty in China, if viewed from the essentialist perspective of identity, its intrinsic core belongs to Chinese historical relics. However, when this artifact appears in a British museum, it may confuse viewers. To address this issue, The British Museum's official website places each artifact in the Chinese section under the larger theme of "China and South Asia," whether by assigning meaning through symbols or by strengthening the overall impression through combinations, The British Museum's website skillfully uses text and images to effectively guide visitors into a specific regional space, thereby establishing basic cognition of that area. Once visitors establish cognition of the "China and South Asia" region, Chinese artifacts within the exhibition area are merely part of a collective, where the focus of identity in specific contexts lies on the exhibit rather than the original identity of the artifacts, thus preliminarily constructing the identity of Chinese artifacts at The British Museum.

4.4.Analysis of the construction of identity for Chinese artifacts on the official website of The British Museum

The constructivist perspective on identity further proposes that identity needs to be realized through discourse. In situations like The British Museum, which accommodates numerous artifacts from other ethnicities, the museum's own identity needs to be reshaped through discourse [56]. Shen Ning summarized the changes in the museum's own definition in the "post-museum" era [57]: during the Renaissance, Alexander's model of collecting war trophies became the prototype of museums, aimed at establishing a sacred paradigm for redeeming the past and becoming the mainstream thought in Europe. This Alexandrian paradigm laid the foundation for the legitimacy of modern museums [58]. In the post-colonial period after World War II, ideas and economy replaced warfare as new means of control [58]. When the International Council of Museums was established in 1946, it defined museums, clarifying their form and functions; over time, the definition of museums has been continuously revised, mainly including collections, exhibition displays, research, and education. In 2019, Ms. Jette Sandahl, Chairperson of the Standing Committee of ICOM, pointed out that the current definition of museums no longer represents the voice of the 21st century and needs to be redefined historically, contextually, and decolonially [59]. The British Museum's official website emphasizes its educational significance and a decolonized, borderless universal significance through text and images [57]. This approach strengthens the close connection between Chinese cultural artifacts and other items with evident colonial undertones to the British Museum, while weakening their own inherent identity recognition.

5.Conclusion

This study selected the "China and South Asia" page from the official website of the British Museum to explore how museums use online platforms to enhance public outreach in the internet era. Through multimodal discourse analysis, this paper conducted an in-depth analysis of the text and images on the website, revealing how the British Museum presents Chinese artifacts. At the same time, through the constructivist perspective of identity theory, this paper explains the strategies used by the website to construct a new identity for Chinese artifacts. Overall, on the official website, the British Museum's identity recognition of Chinese artifacts seems relatively forced, clearly there is still a long way to go. To improve this situation, several measures could be considered. For example, by establishing cooperative relationships with museums in the countries of origin of cultural artifacts, maintaining a close connection between artifacts and their original cultures; official websites can also use images, videos, and other means to showcase the significance of artifacts in their source cultures and their migratory paths, achieving identity recognition construction from the perspectives of awakening cultural memory, stimulating cultural emotions, and highlighting cultural values. This will be more conducive to the effective inheritance of cultural heritage.

References

[1]. Duthie E. The British Museum: an imperial museum in a post-imperial world[J]. Public History Review, 2011, 18: 12-25.

[2]. Abungu, George Okello. 2022. Victims or victors: Universal museums and the debate on return and restitution, Africa’s perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Museum Archaeology. Edited by Alice Stevenson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–88.

[3]. Fincham, Derek. 2012. The Parthenon Sculptures and Cultural Justice. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 23: 1–74.

[4]. Wan Y N. Graduation Resources in News Discourse: Calls for the British Museum to Return Chinese Cultural Artefacts[J]. Journalism and Media, 2024, 5(1): 189-202.

[5]. Miles E. Holocaust Exhibitions On-Line: An Exploration of the Use and Potential of Virtual Space in British and American Museum Websites[J]. The Journal of Holocaust Education, 2001, 10(2): 79-99.

[6]. Zhang Delu. Exploring a Comprehensive Theoretical Framework for Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Chinese Foreign Language, 2009 (1): 24-30.

[7]. Alivizatou M. Museums and intangible heritage: The dynamics of an'unconventional'relationship[J]. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 2006, 17.

[8]. Norris, S. 2004. Analysing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. New York: Routledge.

[9]. Kress, G. & T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

[10]. Halliday, M.A.K. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold, 1994, pp. F 39-57.

[11]. Martin, J.R. English Text: System and Structure [M]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1992.

[12]. O’Halloran K L. Multimodal discourse analysis[J]. The Bloomsbury handbook of discourse analysis, 2011: 249-282.

[13]. Xin Zhiying. New Developments in Discourse Analysis - Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Social Sciences, 2018 (5): 208-211.

[14]. Machin D. What is multimodal critical discourse studies?[J]. Critical discourse studies, 2013, 10(4): 347-355.

[15]. Jones R H. Multimodal discourse analysis[J]. The encyclopedia of applied linguistics, 2012: 1-6.

[16]. Lawler, S. (2008). Identity: Sociological Perspectives, Cambridge: Polity Press.

[17]. Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

[18]. Wendt A. Social theory of international politics[M]. Cambridge university press, 1999.

[19]. Amineh R J, Asl H D. Review of constructivism and social constructivism[J]. Journal of social sciences, literature and languages, 2015, 1(1): 9-16.

[20]. Kim B. Social constructivism[J]. Emerging perspectives on learning, tea

[21]. Grossberg L, Hall S, Du Gay P. Questions of cultural identity[J]. Identity and Cultural Studies: Is that all there is, 1996: 87-107.

[22]. Fairclough, N. (2006). Language and globalization London: Routledge.

[23]. Chen Xinren. Identity Research from a Pragmatic Perspective - Key Issues and Main Paths. Modern Foreign Languages, 2014, 37(5): 702-710.

[24]. Ainsworth S, Hardy C. Critical discourse analysis and identity: Why bother?[J]. Critical discourse studies, 2004, 1(2): 225-259.

[25]. O'Toole, M. The Language of Displayed Art. London: Leicester University Press, 1994, pp. 8-20. Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Images. London: Routledge, 1996, pp. 1, 14, 17.

[26]. Scollon , R. and S.W.Scollon. , Discourse in Place :Language in the Materia l World , London: Routledge, 2003 , pp.3-38.

[27]. Djonov E, Zhao S. From multimodal to critical multimodal studies through popular discourse[M]//Critical multimodal studies of popular discourse. Routledge, 2013: 13-26.

[28]. Way, L. Analysing Politics and Protest in Digital Popular Culture: A Multimodal Introduction. 2020.

[29]. Vihersalo K. Agency in the Girl Effect campaign website: a multimodal discourse analytic study[D]. , 2012.

[30]. Culache O, Obadă D R. Multimodality as a premise for inducing online flow on a brand website: a social semiotic approach[J]. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 149: 261-268.

[31]. Feng Dezhen, Zhang Delu, O'Halloran K. Advances and Frontiers in Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Contemporary Linguistics, 2014, 16(1): 88-99.

[32]. Dai Shulan. The Origin and Progress of Multimodal Discourse Research. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2013 (2): 17-23.

[33]. Liu Yu, Zhang Hongjun. Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Political Documentary Films Shaping National Image. Modern Communication: Journal of Communication University of China, 2018 (9): 118-122.

[34]. Huang Dongqun. Study on the Construction of Fujian Image from the Perspective of Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Zhangzhou Vocational and Technical College, 2022, 24(3): 64-71.

[35]. Zhang Delu, Wang Lu. Synergy of Modalities in Multimodal Discourse and Its Manifestation in Foreign Language Teaching. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2010 (2): 97-102.

[36]. Zhu Yongsheng. Theoretical Foundation and Research Methods of Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2007 (5): 82-86.

[37]. Chang Yiyuan. A Comparative Analysis of Multimodal Features in English and Chinese Websites - A Case Study of Museum Websites in China and the United States. Ningbo University, 2011.

[38]. Zhao Ying, Zhang Xiaohui. Multimodal Representation of Social Participants in Economic Propaganda Discourse - A Case Study of Pudong and Binhai Development Zone Websites. Journal of East China Jiaotong University, 2011, 28(06): 108-113.

[39]. Pan Shuya, Zhang Yuqi. Virtual Presence: The Ritual Chain of Interaction in Online Fan Communities. International Journalism, 2014, 36(09): 35-46. DOI: 10.13495/j.cnki.cjjc.2014.09.003.

[40]. Triandafyllidou A. National identity and the 'other'[J]. Ethnic and racial studies, 1998, 21(4): 593-612.

[41]. He Jinrui, Yan Jirong. On the Transition from Ethnic Identity to National Identity. Journal of Minzu University of China (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 2008, (03): 5-12. DOI: 10.15970/j.cnki.1005-8575.2008.03.006.

[42]. Slater D. Social relationships and identity online and offline[J]. Handbook of new media: Social shaping and consequences of ICTs, 2002: 533-546.

[43]. Falk J H. An identity‐centered approach to understanding museum learning[J]. Curator: The museum journal, 2006, 49(2): 151-166.

[44]. Liu Meijun, Yu Xiao. Perception and Interaction: Enhancing the Interactive Experience in Museums. Furniture and Interior Decoration, 2022, 29(03): 61-65. DOI: 10.16771/j.cn43-1247/ts.2022.03.013.

[45]. Laura Jane Smith, Zhang Yu. The Essence of Heritage is Essentially Intangible: Critical Studies on Heritage and Museum Research. Cultural Heritage, 2018, (03): 62-71.

[46]. Miller C L, Hamell G R. A new perspective on Indian-White contact: Cultural symbols and colonial trade[J]. The Journal of American History, 1986, 73(2): 311-328.

[47]. Pattee H H. Physical and functional conditions for symbols, codes, and languages[J]. Biosemiotics, 2008, 1: 147-168.

[48]. Chkheidze, P., Tho, H. T., & Pasʹko, I. (Eds.). (2015). Symbols in Cultures and Identities in a Time of Global Interchange. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy.

[49]. Lagerkvist C. The Museum of World Culture: A “glocal” museum of a new kind[J]. Scandinavian museums and cultural diversity, 2008: 89-100.

[50]. Halliday M A K. Language and Education: Volume 9[M]. A&C Black, 2007.

[51]. Earle W. Cultural education: Redefining the role of museums in the 21st century[J]. Sociology Compass, 2013, 7(7): 533-546.

[52]. Waterworth J A. Multimedia interaction [M] // Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction. North-Holland, 1997: 915-946.

[53]. Van Dijk, translated by Zeng Qingxiang. News as Discourse. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, 2003.

[54]. Fairclough N. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language[M]. Routledge, 2013.

[55]. Antaki, Charles, and Sue Widdicombe, eds. Identities in talk. Sage, 1998.

[56]. Weber C J. Ainsworth and Thomas Hardy[J]. The Review of English Studies, 1941, 17(66): 193-200.

[57]. Shen Ning. Contemporary Paths to Community Building: An Analysis from the Perspectives of Museum Identity and Memory. The Editorial Department of Journal of Ethnology, 2021, 12(6): 68-76, 123.

[58]. Shen Ning. The Journey of Museums from Temples to the Secular: The British National Museum Institute. China Museums, 2016 (4): 43-48.

[59]. Sandahl J. The museum definition as the backbone of ICOM[J]. Museum International, 2019, 71(1-2): vi-9.

Cite this article

Feng,H. (2024). Exploring the Identity of Chinese Cultural Relics on British Museum Websites Through Multimodal Discourse Analysis: A Case Study of the Official Website. Communications in Humanities Research,40,50-60.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Duthie E. The British Museum: an imperial museum in a post-imperial world[J]. Public History Review, 2011, 18: 12-25.

[2]. Abungu, George Okello. 2022. Victims or victors: Universal museums and the debate on return and restitution, Africa’s perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Museum Archaeology. Edited by Alice Stevenson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–88.

[3]. Fincham, Derek. 2012. The Parthenon Sculptures and Cultural Justice. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 23: 1–74.

[4]. Wan Y N. Graduation Resources in News Discourse: Calls for the British Museum to Return Chinese Cultural Artefacts[J]. Journalism and Media, 2024, 5(1): 189-202.

[5]. Miles E. Holocaust Exhibitions On-Line: An Exploration of the Use and Potential of Virtual Space in British and American Museum Websites[J]. The Journal of Holocaust Education, 2001, 10(2): 79-99.

[6]. Zhang Delu. Exploring a Comprehensive Theoretical Framework for Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Chinese Foreign Language, 2009 (1): 24-30.

[7]. Alivizatou M. Museums and intangible heritage: The dynamics of an'unconventional'relationship[J]. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 2006, 17.

[8]. Norris, S. 2004. Analysing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. New York: Routledge.

[9]. Kress, G. & T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

[10]. Halliday, M.A.K. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold, 1994, pp. F 39-57.

[11]. Martin, J.R. English Text: System and Structure [M]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1992.

[12]. O’Halloran K L. Multimodal discourse analysis[J]. The Bloomsbury handbook of discourse analysis, 2011: 249-282.

[13]. Xin Zhiying. New Developments in Discourse Analysis - Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Social Sciences, 2018 (5): 208-211.

[14]. Machin D. What is multimodal critical discourse studies?[J]. Critical discourse studies, 2013, 10(4): 347-355.

[15]. Jones R H. Multimodal discourse analysis[J]. The encyclopedia of applied linguistics, 2012: 1-6.

[16]. Lawler, S. (2008). Identity: Sociological Perspectives, Cambridge: Polity Press.

[17]. Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

[18]. Wendt A. Social theory of international politics[M]. Cambridge university press, 1999.

[19]. Amineh R J, Asl H D. Review of constructivism and social constructivism[J]. Journal of social sciences, literature and languages, 2015, 1(1): 9-16.

[20]. Kim B. Social constructivism[J]. Emerging perspectives on learning, tea

[21]. Grossberg L, Hall S, Du Gay P. Questions of cultural identity[J]. Identity and Cultural Studies: Is that all there is, 1996: 87-107.

[22]. Fairclough, N. (2006). Language and globalization London: Routledge.

[23]. Chen Xinren. Identity Research from a Pragmatic Perspective - Key Issues and Main Paths. Modern Foreign Languages, 2014, 37(5): 702-710.

[24]. Ainsworth S, Hardy C. Critical discourse analysis and identity: Why bother?[J]. Critical discourse studies, 2004, 1(2): 225-259.

[25]. O'Toole, M. The Language of Displayed Art. London: Leicester University Press, 1994, pp. 8-20. Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Images. London: Routledge, 1996, pp. 1, 14, 17.

[26]. Scollon , R. and S.W.Scollon. , Discourse in Place :Language in the Materia l World , London: Routledge, 2003 , pp.3-38.

[27]. Djonov E, Zhao S. From multimodal to critical multimodal studies through popular discourse[M]//Critical multimodal studies of popular discourse. Routledge, 2013: 13-26.

[28]. Way, L. Analysing Politics and Protest in Digital Popular Culture: A Multimodal Introduction. 2020.

[29]. Vihersalo K. Agency in the Girl Effect campaign website: a multimodal discourse analytic study[D]. , 2012.

[30]. Culache O, Obadă D R. Multimodality as a premise for inducing online flow on a brand website: a social semiotic approach[J]. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 149: 261-268.

[31]. Feng Dezhen, Zhang Delu, O'Halloran K. Advances and Frontiers in Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Contemporary Linguistics, 2014, 16(1): 88-99.

[32]. Dai Shulan. The Origin and Progress of Multimodal Discourse Research. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2013 (2): 17-23.

[33]. Liu Yu, Zhang Hongjun. Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Political Documentary Films Shaping National Image. Modern Communication: Journal of Communication University of China, 2018 (9): 118-122.

[34]. Huang Dongqun. Study on the Construction of Fujian Image from the Perspective of Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Zhangzhou Vocational and Technical College, 2022, 24(3): 64-71.

[35]. Zhang Delu, Wang Lu. Synergy of Modalities in Multimodal Discourse and Its Manifestation in Foreign Language Teaching. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2010 (2): 97-102.

[36]. Zhu Yongsheng. Theoretical Foundation and Research Methods of Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2007 (5): 82-86.

[37]. Chang Yiyuan. A Comparative Analysis of Multimodal Features in English and Chinese Websites - A Case Study of Museum Websites in China and the United States. Ningbo University, 2011.

[38]. Zhao Ying, Zhang Xiaohui. Multimodal Representation of Social Participants in Economic Propaganda Discourse - A Case Study of Pudong and Binhai Development Zone Websites. Journal of East China Jiaotong University, 2011, 28(06): 108-113.

[39]. Pan Shuya, Zhang Yuqi. Virtual Presence: The Ritual Chain of Interaction in Online Fan Communities. International Journalism, 2014, 36(09): 35-46. DOI: 10.13495/j.cnki.cjjc.2014.09.003.

[40]. Triandafyllidou A. National identity and the 'other'[J]. Ethnic and racial studies, 1998, 21(4): 593-612.

[41]. He Jinrui, Yan Jirong. On the Transition from Ethnic Identity to National Identity. Journal of Minzu University of China (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 2008, (03): 5-12. DOI: 10.15970/j.cnki.1005-8575.2008.03.006.

[42]. Slater D. Social relationships and identity online and offline[J]. Handbook of new media: Social shaping and consequences of ICTs, 2002: 533-546.

[43]. Falk J H. An identity‐centered approach to understanding museum learning[J]. Curator: The museum journal, 2006, 49(2): 151-166.

[44]. Liu Meijun, Yu Xiao. Perception and Interaction: Enhancing the Interactive Experience in Museums. Furniture and Interior Decoration, 2022, 29(03): 61-65. DOI: 10.16771/j.cn43-1247/ts.2022.03.013.

[45]. Laura Jane Smith, Zhang Yu. The Essence of Heritage is Essentially Intangible: Critical Studies on Heritage and Museum Research. Cultural Heritage, 2018, (03): 62-71.

[46]. Miller C L, Hamell G R. A new perspective on Indian-White contact: Cultural symbols and colonial trade[J]. The Journal of American History, 1986, 73(2): 311-328.

[47]. Pattee H H. Physical and functional conditions for symbols, codes, and languages[J]. Biosemiotics, 2008, 1: 147-168.

[48]. Chkheidze, P., Tho, H. T., & Pasʹko, I. (Eds.). (2015). Symbols in Cultures and Identities in a Time of Global Interchange. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy.

[49]. Lagerkvist C. The Museum of World Culture: A “glocal” museum of a new kind[J]. Scandinavian museums and cultural diversity, 2008: 89-100.

[50]. Halliday M A K. Language and Education: Volume 9[M]. A&C Black, 2007.

[51]. Earle W. Cultural education: Redefining the role of museums in the 21st century[J]. Sociology Compass, 2013, 7(7): 533-546.

[52]. Waterworth J A. Multimedia interaction [M] // Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction. North-Holland, 1997: 915-946.

[53]. Van Dijk, translated by Zeng Qingxiang. News as Discourse. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, 2003.

[54]. Fairclough N. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language[M]. Routledge, 2013.

[55]. Antaki, Charles, and Sue Widdicombe, eds. Identities in talk. Sage, 1998.

[56]. Weber C J. Ainsworth and Thomas Hardy[J]. The Review of English Studies, 1941, 17(66): 193-200.

[57]. Shen Ning. Contemporary Paths to Community Building: An Analysis from the Perspectives of Museum Identity and Memory. The Editorial Department of Journal of Ethnology, 2021, 12(6): 68-76, 123.

[58]. Shen Ning. The Journey of Museums from Temples to the Secular: The British National Museum Institute. China Museums, 2016 (4): 43-48.

[59]. Sandahl J. The museum definition as the backbone of ICOM[J]. Museum International, 2019, 71(1-2): vi-9.