1. Introduction

Promoting governance optimization through information development is a guiding principle of Chinese-style modernization. The report of the 20th National Congress highlights that the modernization of governance capacity is imperative, emphasizing the need to improve information-based platforms that support grassroots governance. In the new media era, research on grassroots governance tends to focus on the technological role of "information" but pays insufficient attention to the digital transformation of the information subjects. As a key feature of current rural social governance under the rural revitalization initiative, analyzing multi-layered governance from different perspectives holds significant theoretical and practical value. Scholars have proposed numerous related concepts in rural governance research, such as composite governance [1], collaborative governance [2], cooperative governance [3], multi-actor co-governance [4], and comprehensive governance [5]. Among these, multi-layered governance places greater emphasis on the stratification of grassroots social governance. For example, in rural poverty governance, a triadic pattern of formal, semi-formal, and informal governance was identified [6]. This stratified perspective of governance, based on relationships, differs from traditional perspectives of economic or social stratification. Traditional views tend to focus on the influence of class on social structure, for instance, recognizing the interrelated nature of economic factors and social governance structures [7], suggesting that economic differentiation leads to social stratification, which in turn creates new social structures [8]. The stratified perspective of multi-layered governance, however, places greater emphasis on the relationships between governance subjects within the social structure, refining the understanding of rural governance in the context of the new media era.

In the new media era, information is a crucial component of grassroots decision-making, and understanding and optimizing information relationships can benefit many aspects of governance, particularly rural governance within new media contexts. In fact, information as an important lens for organizational research has accumulated substantial theoretical achievements in fields such as structural reform and performance governance, especially in studies examining relationships within specific fields. Urban grassroots governance research suggests that in project-based organizations, information exhibits a hierarchical structure [9]. With the development and expansion of information technology, digital transformation has introduced information as a new resource and variable into the management landscape. These early studies endowed the information perspective with structural connotations, focusing on the relationship between information structure and decision-making mechanisms. They primarily addressed two aspects: first, selecting the optimal organizational decision-making structure for a given information structure; second, examining the optimization mechanisms of the information structure [10]. From the perspective of network relationships, information profoundly affects the effectiveness of organizational governance [11], and information relationships significantly impact the interactions among governance subjects [12]. Stratified governance of information directly relates to the social, environmental, and economic values generated by information [13].

In the process of digital transformation, information technology exerts a significant hierarchical effect on governance subjects [14]. Under the information-based social framework, new organizational models and fundamental characteristics continually emerge across different fields, adjusting the interest structures of various subjects within stable institutional frameworks. This holds great importance for advancing governance modernization in the new media era [15]. Therefore, exploring rural governance in the digital age from the perspective of information offers unique value. This study argues that information relationships and governance structures are key variables influencing rural governance in the new media era. However, the information perspective has rarely been applied in grassroots governance case studies, particularly in discussions on rural governance. Meanwhile, the social structure of traditional rural Chinese villages is characterized by strong "familiarity," which adds complexity and diversity to multi-layered governance, creating opportunities to explore the transformation of information subject relationships in the new media era. Thus, this paper seeks to analyze the internal information relationships in rural governance in the new media era through empirical data, using this as the research focus to explore new characteristics in the governance structure of rural society.

2. Research Methodology and Analytical Framework

Over the past decade, the research team I belong to has conducted fieldwork in the suburbs of Beijing, utilizing questionnaires, interviews, and other methods to explore the relationship between rural life, village governance, and new media technologies. Considering that the evolution of new media and township governance is a gradual process, this study employed participant observation and in-depth interviews, using multi-case and cross-case analysis as the basic logic. Focusing on specific districts and counties, we selected typical areas for in-depth investigation. The research period was chosen to be closer to the present, spanning 2017-2022, with data collected in August 2017, July 2019, and July-August 2022. Surveys were conducted in more than ten townships and villages within the case study districts, and the main primary data came from the oral narratives of 48 farmers. Based on interview transcripts totaling over 200,000 words, combined with the team’s long-term field observation and research foundation, this study explores the technical manifestations and construction features of rural governance in the context of new media.

The case study area is located in the suburbs of Beijing, primarily composed of townships. Over the past decade of urbanization and rural modernization, various villages in this region have faced numerous development scenarios, including land transfers, demolition and relocation, village renovation, illegal construction control, and industrial withdrawal. Different villages have developed multiple governance pathways in the process of governance transitions, providing a typical field for multi-case studies and constructive explanations. From 2011 to 2020, the district government implemented two phases of a project aimed at improving the comprehensive quality of new farmers, each phase lasting five years. This project was aligned with changing farmers’ lifestyles, helping them adapt to the new urbanization scenarios in rural areas by systematically training farmers in a conceptual framework. The project covered 14 townships within the district. Over the ten-year period, the research team selected farmer training venues as the primary sites for surveys, combining questionnaires, in-depth interviews, and participatory observation. Through visits and surveys of township governments, affiliated villages, and other locations, the team formed a general understanding of rural and township governance in the area.

In the summer of 2022, the research team once again conducted fieldwork, focusing on more than ten villages in seven townships. In-depth interviews and participatory observation were conducted with members of village Party branches and village committees (referred to as the "village two committees"), key coordinators of village affairs, and farmers involved in village governance. The interviewees, all farmers, participated in the governance processes of their respective villages. These individuals not only play an important role in rural information dissemination but also serve as witnesses and drivers of the transformation of rural social structures. Their ideas and actions in rural governance directly shape the form of rural governance in the new media era, and they reflect, to a large extent, the practical implications and developmental trends of rural governance in new media contexts. In addition, this study also conducted in-depth interviews with township government officials, ordinary villagers, village staff (such as the teams from science and technology outreach centers), permanent migrant populations, and other stakeholders, providing first-hand evidence from different perspectives on rural governance.

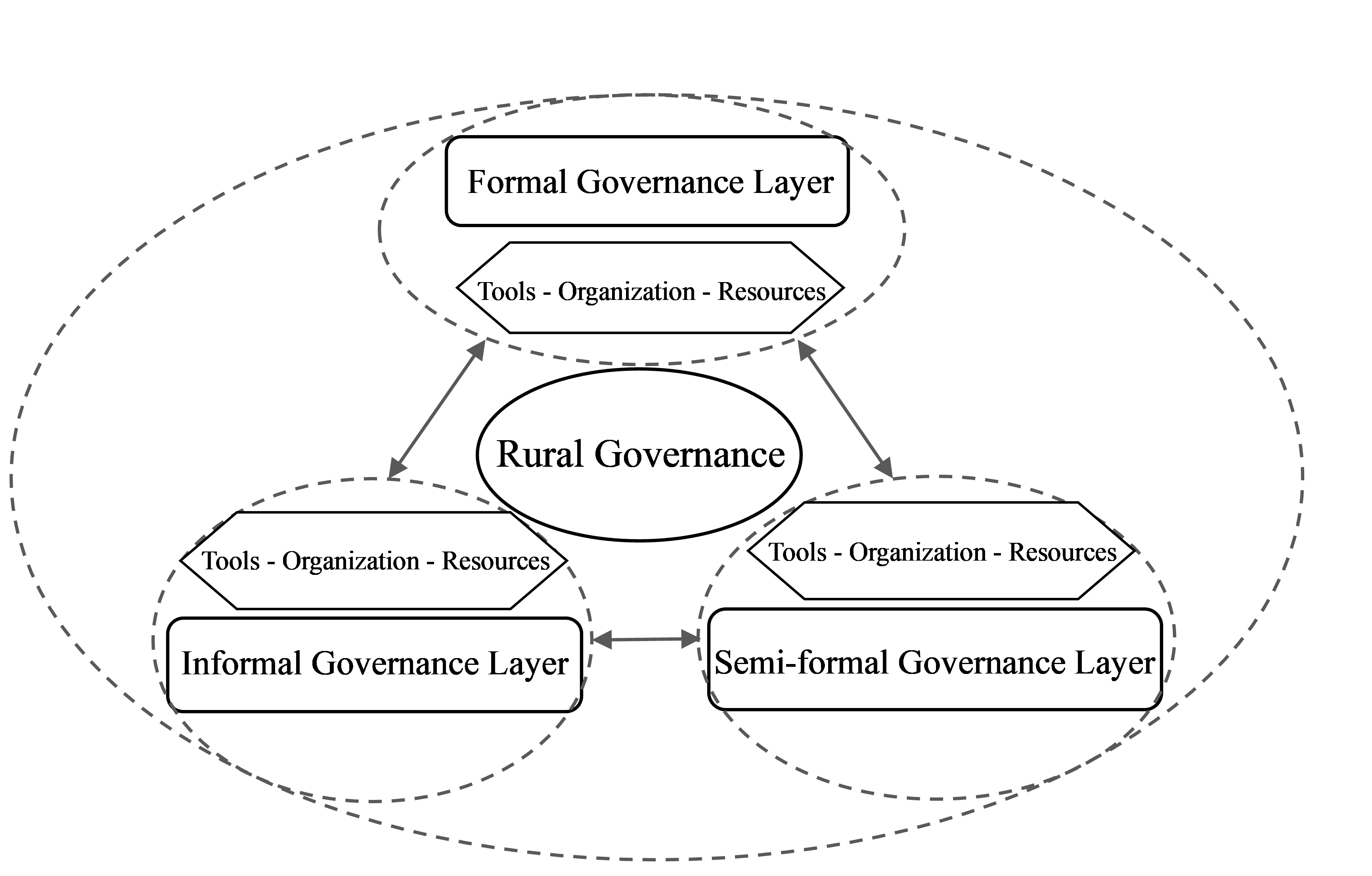

From the perspective of information management and systems theory, stratification provides a basis for understanding the issue of information hierarchy. This paper adopts the management systems methodology in governance research, with a hierarchical perspective as the entry point. Unlike the process perspective, which emphasizes examining different stages of governance, the hierarchical perspective critiques the traditional process-based analytical approach. The traditional approach typically involves processes such as planning, organizing, staffing, directing, coordinating, reporting, and budgeting, while the hierarchical perspective focuses more on the different levels of management work. It categorizes specific functions into three levels: policy management, resource management, and project management [16]. Local management capacity can be enhanced from three dimensions: tools, organizational capacity, and resources [17]. This study links the analytical dimensions of the hierarchical perspective with the multiplicity of rural governance, constructing a "tools-organization-resources" framework to analyze and examine governance at the levels of formal, semi-formal, and informal governance.

Figure 1: Analytical Framework for Multi-layered Rural Governance

This paper approaches the issue of rural governance in the new media era from the perspective of information relationships, combining it with the explanatory framework of multiple governance. It focuses on the issues of information and governance structures in rural governance, based on the perspective of the relationship between governance and information hierarchy. By expanding on previous studies of multiple governance, this paper shifts the focus to the governance subjects, making subject stratification the core of multiple governance research, while also extending attention to the relationship between information and governance, thus exploring governance structures. The "stratification" at these two levels actually includes the stratification of subjects by information and the stratification of objects by information. It is important to note that the process of multiple governance involves a game between different levels of information as well as between different information groups, which inevitably leads to competition between governance subjects. The stratification of information subjects and structures in multiple governance is not independent; instead, it exists in a connected, ongoing manner within the same field, forming a dynamic construction. This dynamic process not only reflects the multidimensional effects produced by the complex interactions between diverse sources of information in the context of new media but also highlights the real need and internal motivation for the participation of multiple subjects in rural governance. Through long-term, continuous field research, this study will attempt to explain the forms of information stratification in rural governance, explore the governance logic and ultimate goals behind this stratification, and provide interpretative pathways within the new media context for the modernization transformation of rural governance in the new media era.

3. The Formation of Information Stratification: The Multiplicity of Information in Rural Governance in the New Media Era

3.1. The Tool Rationality of Information in the Formal Governance Layer

Governance in the new media era emphasizes the technology, efficiency, and rationality brought about by "digitalization." On the one hand, rural development requires preferential policies from public departments, and the formal governance layer of villages must be able to seize opportunities for project implementation through competition in the "administrative contracting" process. On the other hand, against the backdrop of urbanization, the formal governance layer must meet the tool rationality needs of its village, addressing contradictions in the modernization development of the village and seeking breakthroughs in village construction. The formal governance layer reproduces information on the tool level, updates information generationally on the organizational level, and competes for superior information on the resource level, all of which are characteristics of information stratification formed by multiple governance.

At the tool level, the formal governance layer obtains internal village information through means such as villager participation and social networks. By discussing in meetings of the village’s two committees, the formal governance layer forms basic ideas about the tool rationality of village development and selectively disseminates information into the public domain, thereby transforming it into new governance rules or plans. Governance information from public departments is screened by the formal governance layer of the village, which reproduces the texts related to the village. Research on public departments has shown that the localization of innovative policies comes with complex local governance performance and institutional change orientations[18]. At the village level, this information reproduction is characterized by tool rationality and is linked to the authority of the formal governance layer in rural governance. During the demolition of illegal structures in X Village, Z Town, the formal governance layer reinterpreted the public department’s governance text and reproduced the information during the demolition process, transmitting "illegal constructions" as new public information to the villagers. The villagers readily accepted the information, allowing the public information to be implemented, and the village was transformed and governed through this process of information reproduction.

Generational differences in the process of technology diffusion have long been a concern for scholars. Research points out that in the context of new media, information practices in rural governance are more closely related to farmers’ age and educational background[19]. At the organizational level, to make information acquisition and transmission more efficient for the formal governance layer, villages in different townships of the case study area have gradually replaced their village cadres. Young forces are being added to the village’s two committees, with some young entrepreneurs even returning to lead village development. The personnel changes have not only incorporated newer tool rationality information into the formal governance layer but also provided technical support for the organization. Youth in each village often put significant effort into receiving, processing, and transmitting information, especially village affairs information in the formal governance layer. To ensure the continuity of governance, if the village secretary is older, young "reserve cadres" need to be cultivated: "Each village has reserve cadres. If a village does not have (trained) young cadres, (the township) will appropriately assign one, often a department member, to assist the secretary in handling these tasks" (WS20170816, QYYG20220728).

At the resource level, grassroots government, market departments, research institutions, or social organizations are sought to bring multiple resources into village construction. In collaboration with university research teams, X Village in Z Town established a village information governance platform. This tool-rational "digital governance" model surpassed the three forms of "digital governance formalism" proposed by scholars in the practice of public governance: "task-completion type," "political coalition type," and "downward assessment incentive type"[20]. It created a "technical emulation" at the village level to gain an advantage in the "upward" competition for resources. H, a member of X Village’s committee in Z Town, stated that the village’s two committees must "get things done" to gain the villagers’ approval. "Getting things done" refers to tangible improvements, such as turning the village’s former sewage pit into a wetland park through government investment, building the sports field with funding from the sports bureau, and installing streetlights supported by a tourism bureau project. "The roads in the village were repaired by the district’s project" (ZZXH20220720). Whether the formal governance layer can acquire external project information and maintain an advantageous position in information integration is a tool-rational demand of rural governance, making the authority-led governance information of the formal governance layer a core component of the rural governance system.

3.2. Semi-Formal Governance Layer’s Proxy Execution Information

With the advancement of urbanization and new technologies, farmers not only constitute a socioeconomically vulnerable group but also one that is disadvantaged in terms of information inequality. As assistants to the formal governance layer, coordinators or assistant officers are the main personnel of the semi-formal governance layer. Jane Fountain proposed the concept of "technology enactment," which suggests that "information technology is less adopted or applied by decision-makers and more enacted by them" [21]. In rural governance, the basic logic of technology enactment is that the semi-formal governance layer acts as an intermediary to execute the tool-rational information from the formal governance layer. This proxy role is an extension of the mediated diffusion of township government information in the new media era [22]. The semi-formal governance layer typically relies on public and non-public information, such as grassroots government information, village governance decisions, and general opinions of villagers, to construct its own approach, using this as the basis for proxy execution in rural governance. In terms of tools, the semi-formal governance layer is involved in information diffusion, in organizational terms, they judge the information, and in resource terms, they coordinate information. This reflects the characteristic of information stratification formed through multi-level governance.

At the tool level, the work of rural coordinators and assistants highlights this group’s significant role in information transmission. As part of the semi-formal governance layer, coordinators or assistants commonly use WeChat groups or other group communication methods to disseminate the decisions of the formal governance layer, which is a prevalent method in rural governance. Beyond using new media technologies, these informal governance roles often need to execute village-level information by proxy. A young rural assistant from Q Town mentioned, "We (assistants) are essentially the secretary’s assistants. Some of the older secretaries, when the township assigns them work, don’t know how to use a computer. So we still need to step in and complete the tasks for them, effectively assisting all the village staff by proxy" (QYYG20220728). The transition of rural governance tools toward digitization and informatization in the new media era has made the flexible use of information technology a basic skill for the proxy execution by the semi-formal governance layer.

At the organizational level, many of the rural coordinators involved in semi-formal governance are experienced local farmers. With the spread of information technology in rural governance in the new media era, most of them can quickly receive and assess proxy information through new media technologies and make judgments about its operability, coordinating the execution and feedback of information within a certain information space. For instance, in B Town, the cultural coordinator from B Village applied to organize a calligraphy class within the village, saying, "There are quite a few people in our village who love calligraphy, so the township government suggested holding one in our village. We applied, and the government approved it, paid for the teacher, and any resident from nearby villages could come to learn" (BZBJ20220811). To promote good governance in rural areas, many villages previously had university graduate village officials assisting with the work, and now grassroots governments have also assigned rural revitalization coordinators and Party-building assistants to the villages. These individuals help informal governance organizations improve the efficiency of proxy execution in rural governance information.

At the resource level, village coordinators typically maintain various WeChat or QQ groups, or in earlier times, Feixin groups, with township departments and village farmers. Public service information from township departments is often delivered directly to the semi-formal governance layer of the village through platforms like WeChat or QQ, and they then coordinate the work in the village. For example, when organizing a cultural or sports event, the semi-formal governance layer must execute the public service information from the township department by proxy. "The village secretary doesn’t seek us out; we go to the secretary first. If there’s an event, the township department first gathers all the cultural coordinators from each village, like for a dance competition or singing contest. Then, we consult the village secretary; if they agree, the event proceeds; if not, it doesn’t, because the funds have to go through the village’s main account, and if the village can’t provide the funds, it becomes a problem" (QY20170809). Farmers in the semi-formal governance layer mainly interpret the information from an execution standpoint, conveying event details to the villagers and gauging their willingness to participate. Although the formal governance layer is not directly involved in the transmission and reception of this type of information, it plays a decisive role in determining whether such information can receive resource support.

3.3. Informal Governance Layer’s Livelihood Contingency Information

In the process of modernizing rural grassroots governance, a "community-based" governance model has become a focal point for some villages [23]. In recent years, some farmers who participate in village governance neither belong to the two village committees nor take on semi-formal governance roles. They engage in the daily maintenance of specific village affairs and serve as part of the village’s informal governance layer. The livelihoods of these farmers are often closely tied to employment development amidst the rural modernization transition. The semi-formal governance farmers, aside from the young rural workers selected and dispatched by public departments, typically assist in village affairs such as finance, women’s federations, and cultural activities, supporting the members of the two village committees in governance. In contrast, the informal governance layer of farmers has only recently begun participating in rural governance as part of the modernization transition. While the semi-formal governance layer adapts information at a practical level, establishes an information exchange order at an organizational level, and forms cognitive patterns of information at a resource level, the informal governance layer follows this hierarchical information framework developed from multi-level governance.

For example, L, a villager from X village in Z town, has a leg disability and has been working in the village monitoring room since 2018. He is also responsible for signing for all village deliveries. "In 2018, our village secretary wanted to help me earn some extra income due to my physical limitations. The secretary asked, ‘How’s your eyesight?’ I replied, ‘My eyes are fine, the problem is with my legs. My head and heart are fine, and my upper limbs are okay.’ He said, ‘Then why don’t you start monitoring tomorrow?’ And that’s how I began." (ZZXH20220720). From 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily, with a midday break shared with another villager, L spends most of his time in the monitoring room. He receives and records dynamic information from the surveillance cameras and signs for packages. L has even developed his own signature logbook, meticulously recording the daily deliveries. Although the formal governance layer does not impose strict regulations on the working process of the informal governance layer, individuals like L tend to carefully manage their work, viewing the role as crucial to securing their livelihood and minimizing the risk of losing their job.

The informal governance layer relies on building familiar and trusted information relationships with villagers. To better utilize information for improving rural service provision and governance, not only must they have a deep understanding of the information, but it must also be relevant to the recipients, who need the power and motivation to act [24]. Therefore, at an organizational level, the informal governance layer has its own organizational setup to ensure information exchange. Within these small organizations, roles are differentiated, with a clear distinction between those who lead opinions and those who execute tasks. For instance, in L village of D town, the villagers established a poetry society in 2014. By 2019, the society had over 80 members and published 12 poetry books, a poetry collection, and a nursery rhyme album. The society’s members, primarily middle-aged, also included some elderly people around 80 years old. The group extended beyond L village to surrounding towns, with most members having only junior or senior high school education, and about one-quarter of them being women. The society maintained a clear organizational order: "The society has a chairman, vice-chairman, and secretary-general, all of whom are farmers. The chairman used to be a village official, and we elected him. There are fewer people from Beijing who work outside, so most of them work in Beijing but live in the village. The poetry society holds a meeting on the last weekend of every month to assign tasks and engage in learning and exchange. The task is to write poetry because we need to publish books. We do everything ourselves—typesetting, printing, and binding for internal sharing. Most of the funding comes from our own pockets, but we get some support from the town’s publicity department." (LXDM20190717). Even after the village underwent demolition and relocation, the poetry society members stayed in touch via WeChat, phone, and other means to maintain information exchange.

At the resource level, the information resources of the informal governance layer are somewhat linked to the distribution managed by the formal governance layer. Through their participation in village governance, the informal governance layer gains access to livelihood information relevant to their personal development, such as holding informal village governance positions. For instance, villagers in Q village of Y town staffed the village’s epidemic prevention post and occasionally worked as day laborers during busy agricultural seasons. After three years of working at the prevention post, they were still unsure about the exact income they would receive. "(For prevention duty) there doesn’t seem to be a fixed income. We (the staff) haven’t discussed how much we should earn, but at the end of the year, the village doesn’t let us work for free. The amount we get depends on how much the town and village allocate." (YFQX20220809). Similarly, G, a 63-year-old villager, was approached by the village party committee in 2014 to return to the village and lead villagers in forest protection work. "Back then, I was thinking I shouldn’t keep working away from home. My child had just graduated from university and was working. They told me, ‘You don’t need to leave anymore.’ The village needed me, and I couldn’t refuse. It was close to home, and we were all from the same village. So, I took the job. In rural areas, it’s hard to work full-time because everyone has so many things going on. I keep track of everyone’s workdays. If you come in for one day, I mark it down. I keep an accurate tally and pass it to the accountant, who enters it into the system, and the forestry company (outsourced by the town) pays the wages." (ZZXH20220718). Though informal governance layers hold no formal position, they develop a personal understanding of livelihood contingency information based on resource-related information and carry out governance activities accordingly.

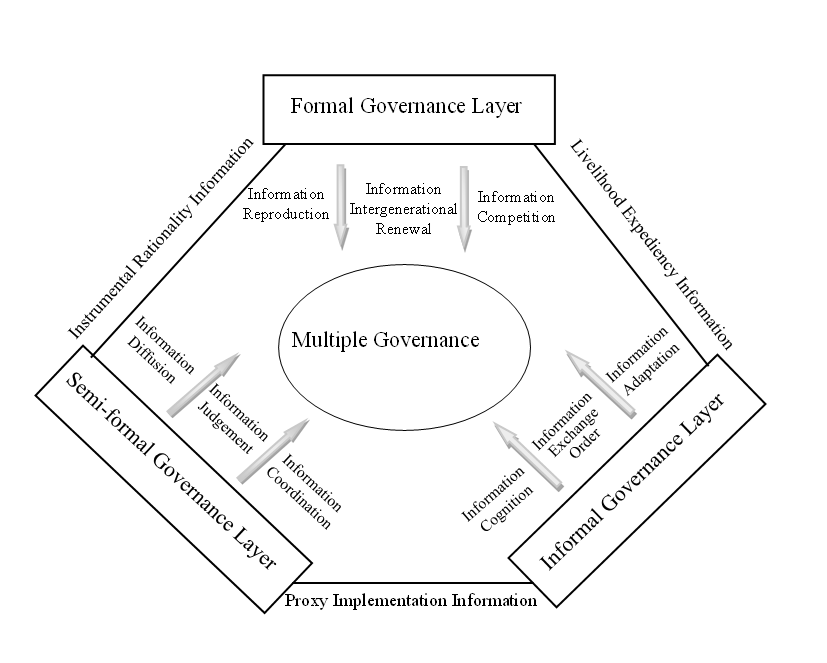

4. Hierarchical Order of Information: Information Structure in Multilayered Rural Governance

Hierarchical information is essentially a form of information order and a manifestation of rural governance practices in the new media era. This hierarchical structure is rooted in rural social order, formed through rural governance practices shaped by the information society. On one hand, information hierarchy is based on the circle-like nature of rural multilayered governance, where distinct forms of information emerge within formal, semi-formal, and informal governance layers. On the other hand, rural governance entities demonstrate differentiated group characteristics within the realm of information practices. This information structure, situated in rural information fields, gives rise to practical significance that explains the transformation of rural society. Analyzing the meaning and scope of information hierarchy offers a perspective for understanding governance practices during this transformation and proposes potential pathways for revitalizing rural construction in the new media era.

Figure 2: Information Structure in Multilayered Rural Governance

4.1. Centralization of Formal Governance Information

In the era of data governance, the relationship between national governance and rural society combines both direct and indirect governance [25]. In the process of modernizing rural governance, formal governance information encompasses the core content of both direct and indirect governance by the state, playing a guiding role in overall village governance. During the field investigation, the village affairs information platform in X Village, Z Town, was identified as a distinctive feature of formal governance, and it is currently being implemented. The village established an intelligent rural platform in 2019, where village affairs information is gradually entered into the system, and future updates are handled through this platform. However, interviews with villagers of different age groups in 2022 revealed that most villagers were unaware of the platform, had no knowledge of its current use, and had not updated their personal information or accessed village affairs information via the mobile application designed for the platform.

Research on rural development and e-government indicates that the main obstacles to such projects include the lack of localized content for rural communities and the insufficient involvement of rural communities in designing rural information and communication technology initiatives [26]. According to the needs analysis for the establishment of the intelligent platform in X Village [27], "Currently, most of the transactional work in X Village relies on traditional office methods, with only a few village cadres from the village committee manually recording statistics. This method makes it difficult to organize complex matters clearly, leading to low work efficiency. Under this traditional village affairs management model, there is a lack of an effective communication platform between the village committee and villagers. The construction of democracy and the rule of law also lacks a proper medium, and village affairs disclosure faces significant limitations. Important notifications are mainly communicated through village broadcasts or by word of mouth between villagers, with no formal communication channels. The village affairs management approach is evidently outdated for today’s circumstances." Although the platform aimed to improve the efficiency of village affairs information dissemination, it did not fully reflect the needs of information recipients, but it did reflect the demand for the digital transformation of formal governance information, representing a manifestation of formal governance information centralization.

4.2. Collaboration of Semi-Formal Governance Information

The semi-formal governance layer, as the main executor of various rural information, collaborates on governance through the use of information tools, the coordination of information organization, and the transmission of information resources. Many villages, besides the two village committees, have experienced coordinators who have long been dedicated to managing village affairs. Groups such as university student village officials, Party-building assistants, and rural revitalization assistants are integrated into the rural governance organizational structure as key talent elements in the context of digital villages. They help address information barriers between public departments and the formal governance layer in rural areas, particularly in governance techniques and information resources.

In the modernized transformation of rural governance, village branches and committees typically have access to more public information about the village. Meanwhile, the "major families" of each village have a longer cycle of information accumulation, particularly regarding interpersonal relationships and family life. Many village conflicts are still mediated by these respected families and their descendants. In Q Village, H Town, there has always been a mediation committee composed of three elders from the village’s three major families. "The mediation committee consists of respected elders in the village. When conflicts arise, people usually go to the village committee first, and if the village committee can’t resolve the issue, they’ll seek help from the mediation committee. These elders act as witnesses when they go to different homes to mediate. For major events in the village like weddings and funerals, the elders are always involved" (HCQD20220725). The semi-formal governance layer’s role in executing formal governance information further emphasizes the collaborative nature of semi-formal governance information.

4.3. Alienation of Informal Governance Information

Surveys across multiple villages show that the informal governance layer and farmers who are less involved in village governance have limited access to public information related to village governance and lack initiative in obtaining it. There is a noticeable alienation between informal and formal governance information. According to the head of S Village, C Town, in 2022, the township government was planning to redevelop the village, with future plans for rural tourism and other industries. However, most villagers were unaware of this governance information. Over-centralization in governance typically manifests through the comprehensive exploitation by governance entities and the "single-track" and "de-emotionalized" nature of governance methods [28]. The informal governance layer also lacks attention to information that affects rural governance. For example, a representative of an agricultural company in X Village, Z Town, who leased village land, restructured the traditional agricultural practices and layout of the village, even though he did not hold an official position in the village. He played a certain role in modernizing the village’s governance structure, yet villagers paid little attention to the information related to village development and the industries within the village.

WeChat groups have provided an online platform for direct interaction between different governance layers within rural communities. However, from the perspective of ordinary villagers, beyond the village group chat, which posts notifications to all members, the platform is often used for practical purposes like "It’s convenient. If our toilet is clogged or broken, we can post in the group, and someone will answer. It’s quite handy. If someone asks for a phone number, people who know will provide it. It’s a big group, and it’s convenient" (YFQX20220809). As a widely used new public media tool in rural governance during the digital era, village WeChat groups provide a platform for sharing multilayered governance information. However, ordinary villagers tend to receive governance information passively through the platform and lack active information awareness, further reflecting the alienation between informal and public governance information in this new media context.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

Promoting governance optimization through information development is the guiding direction proposed by China’s modernization. This article focuses on the internal information relationships in rural governance in the new media era, aiming to understand the manifestations of information stratification in rural governance within new media scenarios. Based on more than a decade of fieldwork in Beijing’s townships by the research team, multiple case studies were conducted using in-depth interviews and participant observation, examining the structural representation of rural governance from an information perspective. Through qualitative analysis, this study conducted a comprehensive examination of field data from different types of villages, exploring the interaction between various actors and the information stratification formed in the digital age and its underlying governance interaction patterns at the micro level. The study shows that in rural societies in the new media era, differentiated information stratification emerges based on multiple governance actors. Specifically, this stratification is reflected in three layers: the formal governance layer’s instrumental rational information, the semi-formal governance layer’s implementation information, and the informal governance layer’s livelihood expedient information. These different types of information form a multi-layered network structure, with the authority-oriented governance information dominated by the formal governance layer being the core part of the rural governance system. The subjects and structures of information within the multiple governance frameworks are interconnected and coexisting in the internal field of rural governance, thus promoting the centralization of formal governance information, the coordination of semi-formal governance information, and the alienation of informal governance information. This results in an orderly information stratification within the multiple governance structures. In different types of rural societies, the "class" characteristics formed by information stratification and the corresponding identity recognition differ, leading to multi-dimensionality and dynamism in rural governance in the new media era. Information stratification deepens the explanatory path for the issue of multiple governance in rural society and offers new perspectives for understanding rural governance in the new media era.

The analytical framework and conclusions of this article provide an interpretative path for exploring the structural manifestations of rural governance in the new media era. From a practical perspective, it offers new materials and perspectives for the integration and optimization of rural governance in the future. On the one hand, the study elucidates the phenomenon of information stratification from the perspective of information relations based on multi-village investigations. On the other hand, by situating the research within the context of multiple governance, it theoretically supplements the study of "multiple governance" in villages in the new media era. The article argues that the core of "digital rural construction" as a national strategy lies in promoting rural informatization development, with rural governance being a crucial component. In the process of social digital transformation, "information" remains eternal, while "transformation" is temporary, and the definition of "information" requires continuous interpretation and experimentation in practice [29]. During this process, the formation of a "multi-layered governance network" becomes possible. How would the issues of information disconnection, instability in information relations, and structural tension caused by asymmetric governance information affect rural governance capacity and potentially lead to changes? This article, following the basic logic of multi-case analysis, provides a comprehensive examination of governance practices in multiple villages to explore the common manifestations of multiple governance from an information perspective and the challenges they pose. Previous studies have shown that with the advancement of modern internet and the introduction of communication technology as a governance tool into rural grassroots societies, village-level autonomy shows a trend of dissolution [30], which aligns with the alienation of "informal governance information" described in this paper. Undoubtedly, "technology" is an important perspective for examining the issue of rural governance in the digital era, and further discussion on the dilemma of village-level governance requires attention to both the integration of technology and governance and the smoothing of governance information and the coordination of governance relations.

Lastly, this topic leaves much room for further research. First, multiple governance offers different interpretative paths, and the information perspective opens up possibilities for us. Multiple governance serves as a supplement to single governance and can also be seen as a "superimposed" model. As an important viewpoint for understanding rural governance, the theoretical space for further exploration of multiple governance still awaits further verification and discussion. Conducting classified analysis of governance structures and diachronic exploration of governance scenarios will help deepen the understanding of the deeper connections between multiple governance and rural governance. Second, the case studies in this article are based on rural areas in the suburbs of Beijing, where the research period is long, and the multi-village cases possess a certain level of typicality. The faster digital growth in mega cities, along with farmers’ wider exposure to new media, provides a real-world scenario for exploring the interaction between information and governance. Therefore, it is believed that there is a connection between information stratification and multiple governance. For rural governance in relatively underdeveloped areas, it is necessary to expand the research field to verify these findings. Lastly, the digital era provides a context for multiple governance in villages and serves as a basis for discussing information stratification. In the digital society, different levels of farmer groups possess their own unique "identities"—as individuals, as members of the governance community, and as the collective rural population. The new media era not only changes the relationship between humans and technology but also shapes new relationships between media and village governance, and between farmers and village governance. The influence mechanism of information relations in new media and rural farmers’ understanding of their information roles require further in-depth exploration in future research.

References

[1]. Bai, H., Li, M., & Liu, Y. (2020). Composite governance: A theoretical explanation of local poverty alleviation pathways—Based on grounded research in 153 poverty-stricken counties. Public Administration Review, 13(01), 22-40, 195-196.

[2]. Yin, M. (2016). Diversity and collaboration: Path selection for constructing new relationships among rural governance actors. Jianghuai Forum, (06), 46-50.

[3]. Wang, X., Wei, L., & Liu, F. (2018). Path construction of rural governance driven by big data in the new era. Chinese Public Administration, (11), 50-55.

[4]. Zhang, Z. (2020). Multi-co-governance: Innovative rural ecological environment governance model under the rural revitalization strategy perspective. Journal of Chongqing University (Social Science Edition), 26(01), 201-210.

[5]. Lang, Y. (2015). Towards holistic governance: The current situation of village politics and the direction of rural governance. Journal of Central China Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 54(02), 11-19.

[6]. Wu, G. (2018). Precise poverty alleviation in the transition of national governance—An explanatory framework for the allocation of poverty alleviation resources in rural China. Journal of Public Administration, 15(04), 113-124, 155.

[7]. Guo, Z., & Guo, J. (2019). The allocation of production factors and governance structure selection in rural industrial revitalization. Journal of Hunan University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition), 22(06), 66-71.

[8]. He, X., & Tan, L. (2015). Governance in endogenously interest-intensive rural areas: A case study of southeast H town. Political Science Studies, (03), 67-79.

[9]. Niu, C., & Li, H. (2020). Research on information relationships in grassroots project systems. Chinese Public Administration, (01), 18-24.

[10]. Arrow, K. J. (1985). Informational structure of the firm. The American Economic Review, (2).

[11]. Huang, C., & Li, S. (2019). Shareholder relationship networks, information advantage, and corporate performance. Nankai Business Review, 22(02), 75-88, 127.

[12]. Luu, N., Cadeaux, J. M., & Ngo, L. V. (2018). Governance mechanisms and total relationship value: The interaction effect of information sharing. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(5), 717-729.

[13]. Luo, H., & Wang, L. (2013). Research on information hierarchy management. Library Construction, (03), 27-29.

[14]. Guan, B., & Liang, J. (2022). The hierarchical utility of digital empowerment. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (03), 14-24, 2.

[15]. Bao, J., & Jia, K. (2019). Research on the modernization of the digital governance system and governance capabilities: Principles, frameworks, and elements. Political Science Studies, (03), 23-32, 125-126.

[16]. Burgess, P. M. (1975). Capacity building and the elements of public management. Public Administration Review, 35, 705-716 (Special Issue).

[17]. Scott, P., & MacDonald, R. J. (1975). Local policy management needs: The federal response. Public Administration Review, 35, 786-794.

[18]. Lin, X. (2015). Intergovernmental organizational learning and policy reproduction: The micro-mechanisms of policy diffusion—A case study of the “urban grid management” policy. Journal of Public Administration, 12(01), 11-23, 153-154.

[19]. Li, H., Niu, C., & Wang, L. (2019). Farmers’ information acquisition and practices in the network era: A survey based on farmer training in suburban Beijing. Journalism and Communication Studies, 26(04), 45-61, 126-127.

[20]. Dong, S., & Dong, X. (2022). Patchwork responses to technological enforcement deviations: An analysis of the occurrence logic of digital governance formalism. Chinese Public Administration, (06), 66-73.

[21]. Jain, E. F. (2004). Constructing the virtual government: Information technology and institutional innovation (G. Shao, Trans.). Beijing: Renmin University of China Press.

[22]. Niu, C. (2022). Agent-based diffusion: Township governance in the context of new media. Chinese Network Communication Research, (01), 82-99, 203.

[23]. Li, Z. (2014). “Community governance”: The modern transformation of grassroots rural governance in China. Journal of Humanities, (08), 114-121.

[24]. Kosec, K., & Wantchekon, L. (2020). Can information improve rural governance and service delivery? World Development, (125).

[25]. Jing, Y. (2018). The logical transition of grassroots governance in rural China—Rethinking the relationship between the state and rural society. Governance Studies, 34(01), 48-57.

[26]. Malhotra, C., Chariar, V. M., Das, L. K., & Ilavarasan, P. V. (2007). ICT for rural development: An inclusive framework for e-governance. Adopting E-governance, 216-226.

[27]. Text from X village research materials, X Village Smart Rural System Requirements Manual.

[28]. Yang, J., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Over-governance: Understanding the connection between the state and individuals in rural China. Public Administration Review, 4(02), 143-166.

[29]. Ren, R., Baier, A., Hinz, T., & Schomaker, H. (2017). On the relationship between information management and digitalization. Business and Information Systems Engineering, 59(6), 475-482.

[30]. Du, J. (2020). Technological dissolution of autonomy—An investigation into the governance dilemmas at the village level under the background of rural informatization. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Science Edition), 20(03), 62-68.

Cite this article

Niu,C.;Li,H.;Gao,C. (2024). Information Stratification: An Understanding of Rural Governance in the New Media Era. Communications in Humanities Research,36,137-149.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2024 Workshop: International Forum on Intelligent Communication and Media Transformation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bai, H., Li, M., & Liu, Y. (2020). Composite governance: A theoretical explanation of local poverty alleviation pathways—Based on grounded research in 153 poverty-stricken counties. Public Administration Review, 13(01), 22-40, 195-196.

[2]. Yin, M. (2016). Diversity and collaboration: Path selection for constructing new relationships among rural governance actors. Jianghuai Forum, (06), 46-50.

[3]. Wang, X., Wei, L., & Liu, F. (2018). Path construction of rural governance driven by big data in the new era. Chinese Public Administration, (11), 50-55.

[4]. Zhang, Z. (2020). Multi-co-governance: Innovative rural ecological environment governance model under the rural revitalization strategy perspective. Journal of Chongqing University (Social Science Edition), 26(01), 201-210.

[5]. Lang, Y. (2015). Towards holistic governance: The current situation of village politics and the direction of rural governance. Journal of Central China Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 54(02), 11-19.

[6]. Wu, G. (2018). Precise poverty alleviation in the transition of national governance—An explanatory framework for the allocation of poverty alleviation resources in rural China. Journal of Public Administration, 15(04), 113-124, 155.

[7]. Guo, Z., & Guo, J. (2019). The allocation of production factors and governance structure selection in rural industrial revitalization. Journal of Hunan University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition), 22(06), 66-71.

[8]. He, X., & Tan, L. (2015). Governance in endogenously interest-intensive rural areas: A case study of southeast H town. Political Science Studies, (03), 67-79.

[9]. Niu, C., & Li, H. (2020). Research on information relationships in grassroots project systems. Chinese Public Administration, (01), 18-24.

[10]. Arrow, K. J. (1985). Informational structure of the firm. The American Economic Review, (2).

[11]. Huang, C., & Li, S. (2019). Shareholder relationship networks, information advantage, and corporate performance. Nankai Business Review, 22(02), 75-88, 127.

[12]. Luu, N., Cadeaux, J. M., & Ngo, L. V. (2018). Governance mechanisms and total relationship value: The interaction effect of information sharing. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(5), 717-729.

[13]. Luo, H., & Wang, L. (2013). Research on information hierarchy management. Library Construction, (03), 27-29.

[14]. Guan, B., & Liang, J. (2022). The hierarchical utility of digital empowerment. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (03), 14-24, 2.

[15]. Bao, J., & Jia, K. (2019). Research on the modernization of the digital governance system and governance capabilities: Principles, frameworks, and elements. Political Science Studies, (03), 23-32, 125-126.

[16]. Burgess, P. M. (1975). Capacity building and the elements of public management. Public Administration Review, 35, 705-716 (Special Issue).

[17]. Scott, P., & MacDonald, R. J. (1975). Local policy management needs: The federal response. Public Administration Review, 35, 786-794.

[18]. Lin, X. (2015). Intergovernmental organizational learning and policy reproduction: The micro-mechanisms of policy diffusion—A case study of the “urban grid management” policy. Journal of Public Administration, 12(01), 11-23, 153-154.

[19]. Li, H., Niu, C., & Wang, L. (2019). Farmers’ information acquisition and practices in the network era: A survey based on farmer training in suburban Beijing. Journalism and Communication Studies, 26(04), 45-61, 126-127.

[20]. Dong, S., & Dong, X. (2022). Patchwork responses to technological enforcement deviations: An analysis of the occurrence logic of digital governance formalism. Chinese Public Administration, (06), 66-73.

[21]. Jain, E. F. (2004). Constructing the virtual government: Information technology and institutional innovation (G. Shao, Trans.). Beijing: Renmin University of China Press.

[22]. Niu, C. (2022). Agent-based diffusion: Township governance in the context of new media. Chinese Network Communication Research, (01), 82-99, 203.

[23]. Li, Z. (2014). “Community governance”: The modern transformation of grassroots rural governance in China. Journal of Humanities, (08), 114-121.

[24]. Kosec, K., & Wantchekon, L. (2020). Can information improve rural governance and service delivery? World Development, (125).

[25]. Jing, Y. (2018). The logical transition of grassroots governance in rural China—Rethinking the relationship between the state and rural society. Governance Studies, 34(01), 48-57.

[26]. Malhotra, C., Chariar, V. M., Das, L. K., & Ilavarasan, P. V. (2007). ICT for rural development: An inclusive framework for e-governance. Adopting E-governance, 216-226.

[27]. Text from X village research materials, X Village Smart Rural System Requirements Manual.

[28]. Yang, J., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Over-governance: Understanding the connection between the state and individuals in rural China. Public Administration Review, 4(02), 143-166.

[29]. Ren, R., Baier, A., Hinz, T., & Schomaker, H. (2017). On the relationship between information management and digitalization. Business and Information Systems Engineering, 59(6), 475-482.

[30]. Du, J. (2020). Technological dissolution of autonomy—An investigation into the governance dilemmas at the village level under the background of rural informatization. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Science Edition), 20(03), 62-68.