1. Introduction

The college admission processes at highly selective universities have long been the subject of media attention, largely because the stakes are so high [1]. In the United States, a college degree, particularly from an Ivy League or similarly prestigious institution, is often viewed as a crucial steppingstone to future success. This perception is not unfounded; research has consistently shown that graduates from highly selective universities enjoy distinct advantages in the job market. For example, studies such as those by Long [2] have demonstrated that graduates from these institutions tend to have higher graduation rates and earn significantly higher salaries compared to those who graduate from less selective schools. The link between college selectivity and future success is further supported by studies focusing on the long-term benefits of attending an elite institution. Dale and Krueger[3] argue that the return on investment in attending a more selective college is significant, especially for students from lower-income backgrounds. Their research shows that, while the benefits of attending a highly selective college are substantial, they are most pronounced for students who might otherwise have fewer opportunities.

Typically, admissions decisions are based on a multifaceted evaluation of candidates, which typically includes academic achievement, extracurricular involvement, leadership qualities, and personal attributes[4]. However, as the competition for limited spots at these prestigious institutions intensifies, the role of race in these decisions has come under increasing examination[2,5]. The concept of race-conscious admissions, often associated with affirmative action policies, was originally designed to promote diversity and address historical inequalities in education. Proponents argue that these policies help create a more diverse educational environment, which benefits all students by exposing them to a wider range of perspectives and experiences[6]. However, critics of race-conscious admissions argue that these policies can lead to reverse discrimination, particularly against Asian American applicants, who are often overrepresented in the applicant pool relative to their share of the population. Studies such as those by Arcidiacono, Kinsler, and Ransom [7] provide evidence that Asian American applicants may be held to higher standards in the admissions process. Their analysis suggests that Asian American applicants to Harvard University were systematically rated lower on subjective criteria, such as personality traits, despite having comparable or superior academic qualifications compared to applicants from other racial groups. This finding raises concerns about the fairness of the admissions process and the potential for racial bias to influence decisions.

The debate over race in college admissions has led to a series of high-profile legal challenges, the most notable of which is the lawsuit against Harvard University brought by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) (referred to hereafter as SFFA vs. Harvard). The case, filed in 2014, brought to light many aspects of Harvard's admissions process that had previously been shrouded in secrecy. Through the legal process, many internal Harvard documents were released in public, including reports from the Office of Institutional Research, that provided detailed data on the demographics of applicants, admits, and matriculants. These documents, along with expert witness reports and trial exhibits, formed the basis of this work that empirically examine whether Harvard's admissions process was biased against Asian American applicants.

On the other hand, in defending its admissions practices, Harvard argued that its process is holistic, and that race is just one of many factors considered in evaluating applicants. The university contends that its approach is consistent with Supreme Court precedents, which have upheld the consideration of race in admissions if it is part of a broader effort to achieve diversity and not the determining factor in admissions decisions [8]. Harvard's defense emphasizes the educational benefits of diversity, which the Supreme Court has recognized as a compelling interest that can justify the use of race in admissions.

The goal of this study is to examine whether there is undeniable evidence of bias in Harvard's admissions process or if the claims of discrimination against Asian American applicants have been exaggerated by the media. To achieve this, a data-driven approach is employed, using the extensive data made available through the Harvard lawsuit. The analysis begins with a thorough review of the internal Harvard documents obtained during the lawsuit, including reports from the Office of Institutional Research and demographic breakdowns of applicants, admits, and matriculants[9]. These documents will provide a foundation for understanding the composition of the applicant pool and how different factors, including race, were considered in the admissions process. Next, statistical analysis is conducted using the data provided in the expert witness reports and trial exhibits. This analysis shows breakdown demographic details and focuses on identifying any patterns of admission outcomes across races, particularly in how Asian American applicants were evaluated compared to applicants from other racial groups. The analysis also examines the role of subjective criteria, such as personality ratings, and whether these were applied consistently across different racial groups. More specifically, this paper reveals multi-dimensional ratings e.g. personal ratings beyond academic performance that are less favored towards Asian Americans, in other words, personal ratings are endogenous variable to the applicant race in the admission model. As such, machine learning model is constructed to predict counterfactual scenarios, i.e., when race is not a factor in the admission process, to evaluate the differences in admission rate if Asian Americans were treated as other races. Finally, the findings from the analysis are compared with the broader academic literature on race and college admissions. This comparison helps to contextualize the results within the ongoing debate over affirmative action and the role of race in admissions. The aim is to provide a balanced and evidence-based assessment of whether Harvard's admissions process is biased against Asian American applicants or whether the claims of discrimination have been overstated.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the literature on affirmative action policies and the legal precedents that have shaped the current landscape of college admissions. Section 3 details the data sources used in the analysis retrieved from legal documents of SFFA vs. Harvard case, including a discussion of the variables and their relevance to the study. Section 4 outlines the methodological approaches used to analyze the data, including the statistical and machine learning techniques employed. Section 5 presents the results of the analysis, with a focus on comparing admission outcomes across racial groups and examining the role of subjective criteria in the admissions process. Finally, Section 6 discusses the implications of the findings, acknowledges the limitations of the study, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Related Works

Affirmative action policies have played an important role in college admissions practices in the United States, designed to promote diversity and address historical inequalities in education. However, these policies have been met with both support and controversy, leading to numerous legal challenges that have shaped the current landscape of college admissions. This section reviews key Supreme Court decisions and their impact on affirmative action, extending in the ongoing debate exemplified by the SFFA vs. Harvard case.

2.1. Supreme Court Decisions and Their Impact

The role of race in college admissions has been a contentious issue in American judicial system for decades. The Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in establishing the legal framework governing the use of race in admissions through several landmark cases:

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke [10]

The first major Supreme Court decision on affirmative action in higher education came in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978). Allan Bakke, a white applicant, sued the University of California, Davis School of Medicine after being denied admission twice, arguing that he had been unfairly excluded due to the university's policy of reserving spots for minority applicants. While the Court ruled that the use of racial quotas in admissions was unconstitutional, it also held that race could be considered as one of many factors in the admissions process to promote diversity. The Bakke decision established a critical precedent: that diversity in higher education is a compelling state interest. However, the Court emphasized that any use of race in admissions must be "narrowly tailored" to achieve this goal, meaning that such policies must not unduly harm members of any racial group. This ruling laid the groundwork for the development of race-conscious admissions policies across the country, setting the stage for future legal challenges. [11]

Grutter v. Bollinger[8]

The Supreme Court revisited the issue of race in admissions in Grutter v. Bollinger[8]. In this case, the Court upheld the university's use of race as part of a holistic review process in its admissions decisions. The majority opinion, delivered by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, reaffirmed the principle that diversity is a compelling interest in higher education and that universities could consider race as one of many factors in their admissions processes. The Grutter decision was significant because it explicitly recognized the educational benefits of a diverse student body. The Court found that these benefits justified the limited use of race in admissions, provided that such policies were narrowly tailored and did not function as a quota system. Moreover, the Court emphasized that race-conscious admissions policies must be time-limited and subject to ongoing review to ensure that they remain necessary and effective. This ruling solidified the legal foundation for affirmative action, but it also imposed stricter scrutiny on how race could be used in admissions.

Fisher v. University of Texas [12]

The Supreme Court's rulings in Fisher v. University of Texas[12] further refined the legal standards for race-conscious admissions policies. Abigail Fisher, a white applicant, sued the University of Texas at Austin after being denied admission, arguing that the university's consideration of race in admissions violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Fisher I[12], the Court did not rule on the constitutionality of the university's admissions policy but instead remanded the case to the lower courts for further review, emphasizing the need for "strict scrutiny." This means that the university had to prove that its use of race was narrowly tailored to achieve the goal of diversity and that no workable race-neutral alternatives existed. In Fisher II [12], the Supreme Court upheld the University of Texas at Austin's admissions policy, finding that it met the strict scrutiny standard. The majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, reaffirmed that universities could consider race as part of a holistic admissions process. However, the decision also underscored the importance of ongoing review and refinement of such policies to ensure that they are narrowly tailored and that race-neutral alternatives have been fully explored. These Supreme Court decisions have collectively shaped the legal landscape for affirmative action in college admissions. They have established that while race can be considered in the admissions process to promote diversity, such consideration must be narrowly tailored, time-limited, and subject to rigorous examination.

The SFFA vs. Harvard Case [13]

The legal debate over affirmative action reached a new level of intensity with the lawsuit filed by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) against Harvard University. The SFFA accused Harvard of discriminating against Asian American applicants by holding them to higher standards than applicants from other racial groups. This case has become one of the most significant challenges to affirmative action in recent years [13]. Specifically, SFFA claimed that Harvard systematically rated Asian American applicants lower on subjective criteria such as personal ratings, despite their strong academic qualifications. These personal ratings, which assess qualities like leadership and likability, were alleged to be biased against Asian American applicants, leading to their underrepresentation in the admitted class [7]. In response, Harvard defended its admissions practices by arguing that its process was fully consistent with Supreme Court precedents. Harvard contended that its consideration of race was part of a holistic review process aimed at achieving a diverse student body, which the Supreme Court had recognized as a compelling interest. The university also pointed to its internal Office of Institutional Research reports, which showed that race was just one of many factors considered in admissions and that there was no evidence of racial balancing or quotas (Plaintiff Expert Witness Opening Report).

The SFFA vs. Harvard case brought to the forefront the complexities of race-conscious admissions policies and the challenges of balancing diversity with fairness. The case also highlighted the difficulties of implementing and defending affirmative action policies in a legal environment that demands strict examination and the consideration of race-neutral alternatives. The Supreme Court's decision in favor of SFFA on the case essentially ends the future of affirmative action in higher education [14].

2.2. Academic Perspectives on Affirmative Action and Race-Conscious Admissions

The legal debates to affirmative action, including the SFFA vs. Harvard case, have sparked considerable academic debate. Scholars have examined the implications of race-conscious admissions policies from various perspectives, including their impact on diversity, educational outcomes, and social equity.

Proponents of affirmative action argue that race-conscious admissions policies are essential for creating a diverse educational environment, which benefits all students by exposing them to a broader range of perspectives and experiences [6]. Research has shown that diversity in the classroom leads to improved critical thinking skills, greater cultural awareness, and better preparation for a globalized workforce [15]. Critics, however, contend that affirmative action can lead to reverse discrimination and that race-neutral alternatives should be pursued to achieve diversity. Studies like those by Arcidiacono et al. [7] suggest that race-conscious admissions policies may unfairly disadvantage certain groups, such as Asian Americans, who are often overrepresented in applicant pools relative to their share of the population. These scholars argue that admissions policies should focus on socioeconomic status, geographic diversity, or other factors that do not involve race, thereby promoting diversity without the potential for racial bias. The ongoing debate over affirmative action reflects the broader tensions in American society regarding race, equality, and merit. As the legal landscape continues to evolve, so too will the policies and practices about college admissions.

3. Data in the SFFA vs. Harvard Case

This section provides an overview of the data sources and variables utilized in the analysis of the SFFA v. Harvard case. The analysis draws from a rich collection of applicant-level data, expert witness reports, and trial exhibits. These sources are crucial for understanding the admission patterns at Harvard University and assessing the role of race in its holistic admissions process.

3.1. Data sources

3.1.1. Applicant-Level Data (Classes of 2014–2019)

The core dataset consists of applicant-level data from the Classes of 2014 to 2019, which was produced by Harvard University during the litigation. This dataset includes detailed information on each applicant's demographic background, academic and extracurricular achievements, personal ratings, and final admission outcomes. The dataset's comprehensiveness allows for an in-depth analysis of how different factors, including race, influence admissions decisions.

Key variables from this dataset include:

• Race/Ethnicity: Categorized as African American, Asian American, Hispanic, White, and others.

• Academic Index: A composite score based on standardized test scores and high school GPA, representing the academic qualifications of applicants.

• Personal Rating: An assessment of an applicant's personality, leadership, and likability, as evaluated by the admissions committee.

• Extracurricular Rating: An evaluation of an applicant's participation and achievements in extracurricular activities.

• Athletic Rating: A rating based on the applicant's athletic abilities and participation in sports.

• Legacy Status: Whether the applicant is a child of Harvard alumni.

• Admission Outcome: The final decision on the applicant's admission (admitted or rejected).

3.1.2. Document 415-8: Plaintiff’s Expert Witness Opening Report

[13] Document 415-8 is the opening report of the plaintiff’s expert witness, economist Peter Arcidiacono. This report provides a statistical analysis of the admissions data, focusing on the impact of race on admission outcomes. Arcidiacono's analysis is central to the plaintiff's argument that Harvard's admissions process discriminates against Asian American applicants. The report includes regression analyses and other statistical methods to isolate the effect of race from other factors in the admissions process.

3.1.3. Document 415-9: Plaintiff’s Expert Witness Rebuttal Report

[9] Document 415-9 is the rebuttal report by Peter Arcidiacono, which responds to the critiques and analyses presented by Harvard's expert witnesses. This report further refines the statistical models and addresses potential biases or inaccuracies in the original analysis. It also emphasizes the importance of considering race-neutral alternatives in admissions and argues that Asian American applicants are systematically disadvantaged in Harvard’s holistic review process.

3.1.4. Trial Exhibit DX 042: Demographic Breakdown of Applicants, Admits, and Matriculants

[16] Trial Exhibit DX 042 provides a demographic breakdown of applicants, admitted students, and matriculants at Harvard. This exhibit is essential for understanding the racial composition of the applicant pool compared to the admitted and enrolled students. It highlights disparities in admission rates among different racial groups and serves as evidence for claims of racial balancing or discrimination.

3.1.5. Trial Exhibit P009: Harvard Office of Institutional Research (OIR) Report

[17] Trial Exhibit P009 is a report from Harvard's Office of Institutional Research (OIR) that examines the role of race in admissions. The report includes internal analyses conducted by Harvard, which assess whether race is a determining factor in admissions decisions. It provides insights into how Harvard's admissions office uses race in its holistic review process and how this practice aligns with the university's diversity goals.

3.1.6. Trial Exhibit P028: Harvard OIR Report on Admissions

[18] Trial Exhibit P028 is another report from Harvard's OIR, focusing specifically on the outcomes of the admissions process. This report includes statistical analyses similar to those in the P009 report but with a focus on the distribution of academic and non-academic ratings across different racial groups. It serves as a critical piece of evidence in understanding the potential biases in the personal rating component of Harvard's admissions process.

3.2. Variables Descriptions

The variables extracted from these sources are crucial for analyzing the fairness and effectiveness of Harvard's admissions process. Each variable provides a lens through which the impact of race and other factors on admission outcomes can be evaluated.

3.2.1. Academic Index

The Academic Index is a composite score that combines standardized test scores (such as the SAT or ACT) and high school GPA. This index is a critical predictor of academic success at Harvard and is heavily weighted in the admissions process. The analysis of the Academic Index is particularly relevant in assessing whether applicants with similar academic qualifications receive different outcomes based on their race.

3.2.2. Personal Rating

The Personal Rating is one of the most contentious variables in the analysis. This rating assesses an applicant's personality, character, leadership qualities, and likability. The subjective nature of this rating has led to allegations of bias, particularly against Asian American applicants, who, according to the plaintiff's analysis, tend to receive lower personal ratings compared to other racial groups. Understanding how the Personal Rating is assigned and its impact on admission decisions is crucial for evaluating the fairness of Harvard’s holistic review process.

3.2.3. Admission Outcome by Academic Index Deciles

The table provided below represents the admission outcome percentages based on Academic Index deciles, further broken down by race. This table illustrates how applicants within the same academic decile fare differently in the admissions process, depending on their race. The disparities observed in this table suggest that factors other than academic qualifications, including race, play a significant role in admission outcomes.

Table 1: Admission outcome by academic index deciles across races

Decile |

African American |

Asian American |

Hispanic |

White |

1 |

0.044 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2 |

0.976 |

0.188 |

0.252 |

0.380 |

3 |

4.880 |

0.748 |

1.892 |

0.422 |

4 |

11.796 |

0.872 |

5.572 |

1.812 |

5 |

21.148 |

2.034 |

8.610 |

2.372 |

6 |

27.510 |

2.864 |

13.458 |

4.010 |

7 |

39.474 |

3.874 |

16.694 |

4.452 |

8 |

44.530 |

5.548 |

22.926 |

7.326 |

9 |

57.286 |

7.002 |

27.372 |

9.950 |

10 |

57.062 |

12.566 |

29.570 |

14.894 |

Table 1 shows that while Asian American applicants have higher academic qualifications (reflected by their distribution in the top deciles), their admission rates are lower compared to African American, Hispanic, and White applicants in the same deciles. This discrepancy raises important questions about the role of non-academic factors, such as the Personal Rating, in shaping these outcomes.

3.2.4. Race/Ethnicity

The Race/Ethnicity variable is central to the analysis of affirmative action policies. By comparing admission outcomes across different racial groups, the analysis aims to identify whether race is used appropriately within the legal constraints established by Supreme Court precedents. The relevance of this variable is particularly evident in the statistical models that seek to determine the extent to which race influences admissions decisions independently of other factors.

3.3. Stylized Facts

This section presents the stylize facts of the data, focusing on comparing admission outcomes across racial groups and examining the role of subjective criteria in Harvard's admissions process. The findings are based on the applicant-level data and expert reports discussed in the previous sections. The analysis aims to provide insights into how race and other factors influence admission decisions, particularly when academic competencies are taken into account. This apparent discrepancy raises important questions about the use of subjective criteria such as personal ratings in the admissions process.

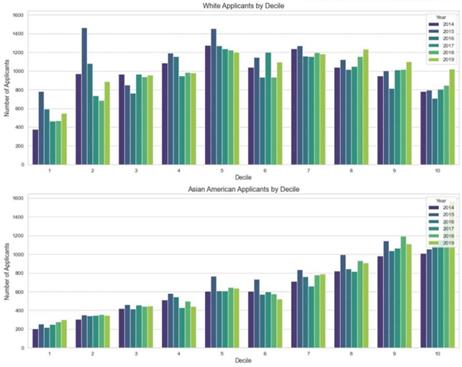

Figure 1 presents comparing the distribution of White and Asian American applicants across deciles by academic competence over years 2014-2019. The distribution of White applicants is relatively uniform across the deciles. However, there's a noticeable dip in certain mid-deciles (e.g., 4, 5) and an increase in higher deciles (8-10). The distribution of Asian American applicants shows a clear trend towards higher academic competence. A significant proportion of Asian American applicants fall into the top deciles (8-10), indicating that they tend to have higher academic qualifications compared to their White counterparts. The data suggests that Asian American applicants are, on average, more academically competent, as evidenced by their higher concentration in the top deciles. Despite their higher academic competence, Asian American applicants face lower admission rates compared to White applicants. This suggests that factors beyond academic competence play a significant role in admissions decisions, which may include non-academic ratings, holistic review processes, or other criteria. Moreover, the distribution appears consistent across the years from 2014 to 2019, indicating a persistent trend over time. This figure highlights a potential disparity in the admission process, where even though Asian American applicants tend to be more academically qualified, their chances of admission are not correspondingly higher. This points to the broader issue of the role of race and holistic admissions criteria in college admissions, which is central to the discussion in the Harvard case.

Figure 1: Admission rate between Asian American applicants and White applicants across academic index deciles in years 2014-2019

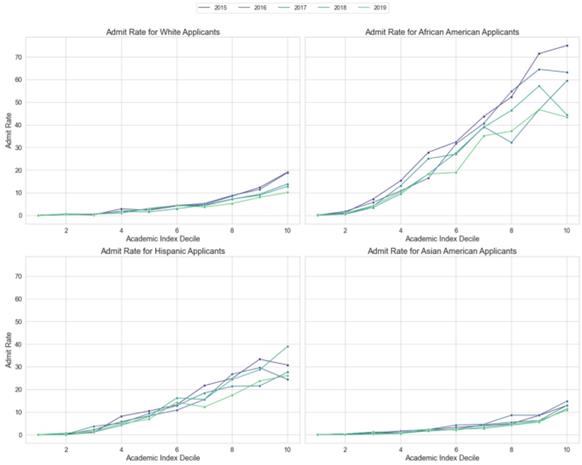

Figure 2 extend the findings for admission rates across different racial groups, including Asian American, White, African American, and Hispanic applicants, based on academic performance (deciles) from 2014 to 2019. The admission rates for African American applicants rise with academic performance, but the increase might be less steep compared to Asian American and White applicants. The trend indicates that African American applicants with lower academic ratings are admitted at relatively higher rates in lower deciles compared to other groups. This suggests that factors other than academic performance, possibly including affirmative action or holistic review criteria, play a significant role in the admission process for African American applicants. Similar to African American applicants, Hispanic applicants might be benefiting from holistic review processes or race-conscious admissions policies, leading to relatively higher admission rates in lower academic deciles.

Overall, admission rates generally increase with academic performance across all racial groups, which is expected. However, the rate of increase and the absolute admission rates vary among the groups. In particular, Asian American and White Applicants show similar trends, with admission rates strongly tied to academic performance. African American and Hispanic Applicants have relatively higher admission rates at lower deciles, indicating that factors beyond academic performance are likely considered more heavily in their admissions. In fact, while academic performance is a crucial factor in admissions, non-academic factors, including possibly race-conscious admissions policies, influence the outcomes differently for different racial groups. This highlights the complexity of the admissions process and the role of holistic review in achieving diversity in college admissions.

Figure 2: Admission rate across applicants from different racial groups across academic index deciles in years 2014-2019

4. Counterfactual Analysis

The previous section reveals that multi-dimensional ratings e.g. personal ratings beyond academic performance are less favored towards Asian Americans, in other words, personal ratings given to applicants are considered endogenous with respect to the applicant’s race. This endogeneity arises because race might influence the personal ratings in ways that could bias the estimates of the effect of these ratings on admission outcomes. To address this, we will use a machine learning counterfactual imputation methodology to first predict personal ratings and then use these predicted ratings in the admission outcome model. In other words, we aim to estimate the personal ratings that would be assigned independently of the applicant’s race, and then use these predicted ratings to estimate the effect of personal ratings on admission outcomes.

Building on the potential outcomes framework by Neyman-Rubin, the goal is to obtain the average treatment effect of being Asian American on the admission outcomes. The following assumptions are made to ensure the validity of the method:

Step 1: Model Assumptions

• No anticipatory effects: Applicants and raters do not anticipate or alter their behavior based on the race of applicants.

• Stability of the counterfactual function: The relationship between personal ratings and other covariates is stable across racial groups.

• Independence of covariates from treatment (applicant’s race): The covariates used to predict personal ratings are independent of the applicant's race after controlling for the predicted personal ratings.

Step 2: Machine Learning Model for Personal Ratings

a. Predicting Personal Ratings:

We will first model the personal ratings using pre-existing applicant data, excluding the direct influence of race. Let \( i \) represent an applicant. Let \( Y_i(PR) \) represent the personal rating for applicant \( i \) and \( X_i(PR) \) represent the set of covariates (e.g., academic performance, extracurricular activities, essays) used to predict the personal rating. The model is expressed as:

\( Y i PR =M X i PR + ε i (1) \)

where \( M() \) is the machine learning model used (e.g., linear regression), and \( \varepsilon_i \) represents the error term.

b. Assumption Validation:

We assume that the relationship in the above model is stable across racial groups and time periods. This allows us to use the predicted personal ratings as an unbiased input into the subsequent admission model.

Step 3: Predicting Personal Ratings with Machine Learning

a. Estimating Personal Ratings:

Using the machine learning model trained on non-racial covariates, predict the personal ratings for each applicant:

\( Y i PR = M X i PR (2) \)

These predicted ratings are used in place of the actual personal ratings in the admission outcome model.

b. Residual Analysis:

Similar to the cross-validation approach in the original empirical strategy, we compute the residuals from the machine learning model to check for biases. These residuals can also be used as additional covariates in the admission outcome model to further control for unobserved factors.

Step 4: Admission Outcome Model

a. Modeling Admission Outcomes:

In the admission model, the dependent variable is the admission outcome (admitted or not admitted), denoted by \( Y_i\left(A\right) \) . The independent variables include the predicted personal ratings \( \widehat{Y_i}\left(PR\right) \) , other applicant characteristics \( X_i \) , and potentially the residuals from the personal ratings model \( \epsilon_i \) :

\( Y i A = β 0 + β 1 Y i PR + β 2 X i + β 3 ϵ i + ε i ( 3) \)

b. Estimation:

Estimate the model using the predicted personal ratings \( \widehat{Y_i}\left(PR\right) \) and other covariates. This will allow us to obtain unbiased estimates of the effect of personal ratings on admission outcomes.

Step 5: Validation and Causal Inference

a. Cross-Validation:

Use cross-validation techniques to validate the predictive power of the model and ensure that the counterfactual scenario (where personal ratings are predicted independently of race) is robust.

b. Causal Effect Estimation:

Finally, calculate the causal effect of the predicted personal ratings on admission outcomes. This can be done by comparing the actual admission outcomes with the counterfactual predictions generated by the model.

\( α= i=1 N Y i A − Y i A N (4) \)

Where \( N \) is the number of applicants, \( Y_i\left(A\right) \) is the observed admission outcome, and \( \widehat{Y_i}\left(A\right) \) is the predicted admission outcome under the counterfactual scenario.

By employing this machine learning-based empirical strategy, we can address the endogeneity of personal ratings to applicant race and obtain a more accurate estimate of the impact of personal ratings on college admission outcomes. This approach ensures that the model’s estimates are not biased by the potential influence of race on personal ratings, leading to more credible and reliable results in the study.

5. Results

In this section, we present the results of our counterfactual analysis, where we estimate the potential number of additional Asian American admits under a scenario where they receive personal ratings similar to those of White applicants. This analysis leverages the machine learning model described in the empirical strategy to generate a theoretical upper bound of admissions for Asian American students based on their academic performance.

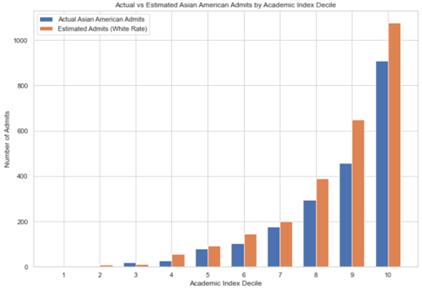

Figure 3: Comparisons of actual and hypothetical Asian American admission outcomes across academic index deciles

The Figure 3 compares the actual number of Asian American admits to the estimated number under the counterfactual scenario where Asian Americans receive the same personal ratings as White applicants. The x-axis represents the Academic Index Decile, and the y-axis represents the number of admits.

The counterfactual scenario predicts a substantial increase in the number of Asian American admits, particularly for students in the higher academic index deciles (8-10). This suggests that if Asian Americans received similar personal ratings to White applicants, their admission rates would be significantly higher. The model estimates that Asian Americans would receive approximately 27% more admissions overall under the counterfactual scenario. This increase is especially pronounced in the higher deciles, where the academic performance is stronger. For instance, in the top decile, the estimated number of admits is significantly higher than the actual number. The results highlight the potential impact of personal ratings on admission outcomes. If personal ratings were assigned equitably across racial groups, it could lead to a more balanced representation of Asian American students in the admitted class, particularly those with strong academic credentials. Furthermore, the majority of the increase in admits occurs in the top academic deciles, indicating that high-performing Asian American students are the most affected by disparities in personal ratings. This suggests that the current admission practices may disproportionately disadvantage Asian American students with strong academic profiles.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the role of various factors in the college admission process, with a particular focus on the impact of personal ratings on Asian American applicants. Our analysis did not find significant bias against Asian American applicants in terms of academic and extracurricular ratings. However, strong differences were observed in non-academic ratings, such as personal ratings, across different racial groups.

When we factored these differences into the admission model through hypothetical scenarios, the results showed that the admission outcomes for Asian American applicants could have increased by approximately 27% if they had received similar personal ratings to White applicants. This finding suggests that while academic and extracurricular achievements are assessed fairly, non-academic ratings like personal evaluations may be a source of bias, influencing the overall admission outcomes.

The admissions data, therefore, may suggest a potential bias that warrants deeper analysis. The current emphasis on academics and quantifiable achievements, while critical, may inadvertently limit the diversity of Asian American applicants, failing to fully recognize and appreciate each individual’s unique journey and personal qualities.

To build on these findings, future research should consider combining quantitative data with qualitative studies to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the admissions process. Surveys and interviews with key stakeholders, such as applicants, admission officers, and educators, could provide valuable insights into the subjective aspects of the process and highlight areas where bias may occur.

Additionally, applying natural language processing (NLP) techniques to analyze the language and sentiment used in recommendation letters or personal ratings could help identify patterns that might indicate bias based on race, gender, or socioeconomic status. This approach could uncover subtle forms of bias that may not be immediately apparent but have a significant impact on admissions decisions.

By expanding the scope of research to include these methodologies, we can contribute to a more equitable and transparent college admission process, ensuring that all applicants are evaluated on their individual merits and personal journeys.

References

[1]. New York Times. “This Is Peak College Admissions Insanity”. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/01/opinion/college-admissions-applications.html.

[2]. Long, Mark C. “Race and College Admissions: An Alternative to Affirmative Action?” Review of Economics and Statistics 86, no. 4 (November 2004): 1020–33. https://doi.org/10.1162/0034653043125211.

[3]. Dale, Stacy B., and Alan B. Krueger. "Estimating the effects of college characteristics over the career using administrative earnings data." Journal of human resources 49, no. 2 (2014): 323-358.

[4]. Niessen, A. Susan M., and Rob R. Meijer. "On the use of broadened admission criteria in higher education." Perspectives on Psychological Science 12.3 (2017): 436-448.

[5]. Espenshade, Thomas J., and Alexandria Walton Radford. No longer separate, not yet equal: Race and class in elite college admission and campus life. Princeton University Press, 2009.

[6]. Espenshade, Thomas J., Chang Y. Chung, and Joan L. Walling. “Admission Preferences for Minority Students, Athletes, and Legacies at Elite Universities*.” Social Science Quarterly 85, no. 5 (December 2004): 1422–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00284.x.

[7]. Arcidiacono, Peter, Josh Kinsler, and Tyler Ransom. “Asian American Discrimination in Harvard Admissions.” European Economic Review, no.144:104079, 2022 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3586200.

[8]. Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

[9]. “Plaintiff Expert Witness Rebuttal Report.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), Document 415-9, 2018. https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/massachusetts/madce/1:2014cv14176/165519/415/2.html.

[10]. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978)

[11]. Kirkelie, Steven M. "Higher education admissions and diversity: The continuing vitality of Bakke v. Regents of the University of California and an attempt to reconcile Powell's and Brennan's opinions." Willamette L. Rev. 38 (2002): 615.

[12]. Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, 570 U.S. 297 (2013); 579 U.S. (2016).

[13]. “Plaintiff Expert Witness Opening Report.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), Document 415-8, 2017. https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/massachusetts/madce/1:2014cv14176/165519/415/1.html.

[14]. Totenberg, Nina. "Supreme Court guts affirmative action, effectively ending race-conscious admissions." (2023). NPR https://www.npr.org/2023/06/29/1181138066/affirmative-action-supreme-court-decision

[15]. Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). "Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes." Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 330-366.

[16]. “Trial Exhibit DX 042. Demographic Breakdown of Applicants, Admits, and Matriculants.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/D042.pdf.

[17]. “Trial Exhibit P009. Office of Institutional Research report, ‘Admissions Part II: Subtitle’.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/P009.pdf.

[18]. “Trial Exhibit P028. Office of Institutional Research report, ‘Demographics of Harvard College Applicants’.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/P028.pdf.

Cite this article

Sun,J. (2024). The Diversity in College Admission: A Study of Asian American Applicants in Harvard Judicial Case. Communications in Humanities Research,42,159-172.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. New York Times. “This Is Peak College Admissions Insanity”. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/01/opinion/college-admissions-applications.html.

[2]. Long, Mark C. “Race and College Admissions: An Alternative to Affirmative Action?” Review of Economics and Statistics 86, no. 4 (November 2004): 1020–33. https://doi.org/10.1162/0034653043125211.

[3]. Dale, Stacy B., and Alan B. Krueger. "Estimating the effects of college characteristics over the career using administrative earnings data." Journal of human resources 49, no. 2 (2014): 323-358.

[4]. Niessen, A. Susan M., and Rob R. Meijer. "On the use of broadened admission criteria in higher education." Perspectives on Psychological Science 12.3 (2017): 436-448.

[5]. Espenshade, Thomas J., and Alexandria Walton Radford. No longer separate, not yet equal: Race and class in elite college admission and campus life. Princeton University Press, 2009.

[6]. Espenshade, Thomas J., Chang Y. Chung, and Joan L. Walling. “Admission Preferences for Minority Students, Athletes, and Legacies at Elite Universities*.” Social Science Quarterly 85, no. 5 (December 2004): 1422–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00284.x.

[7]. Arcidiacono, Peter, Josh Kinsler, and Tyler Ransom. “Asian American Discrimination in Harvard Admissions.” European Economic Review, no.144:104079, 2022 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3586200.

[8]. Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

[9]. “Plaintiff Expert Witness Rebuttal Report.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), Document 415-9, 2018. https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/massachusetts/madce/1:2014cv14176/165519/415/2.html.

[10]. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978)

[11]. Kirkelie, Steven M. "Higher education admissions and diversity: The continuing vitality of Bakke v. Regents of the University of California and an attempt to reconcile Powell's and Brennan's opinions." Willamette L. Rev. 38 (2002): 615.

[12]. Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, 570 U.S. 297 (2013); 579 U.S. (2016).

[13]. “Plaintiff Expert Witness Opening Report.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), Document 415-8, 2017. https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/massachusetts/madce/1:2014cv14176/165519/415/1.html.

[14]. Totenberg, Nina. "Supreme Court guts affirmative action, effectively ending race-conscious admissions." (2023). NPR https://www.npr.org/2023/06/29/1181138066/affirmative-action-supreme-court-decision

[15]. Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). "Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes." Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 330-366.

[16]. “Trial Exhibit DX 042. Demographic Breakdown of Applicants, Admits, and Matriculants.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/D042.pdf.

[17]. “Trial Exhibit P009. Office of Institutional Research report, ‘Admissions Part II: Subtitle’.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/P009.pdf.

[18]. “Trial Exhibit P028. Office of Institutional Research report, ‘Demographics of Harvard College Applicants’.” In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College et al., Civil Action No. 14-14176-ADB (D. Mass), 2018. https://github.com/tyleransom/SFFAvHarvard-Docs/blob/master/TrialExhibits/P028.pdf.